No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

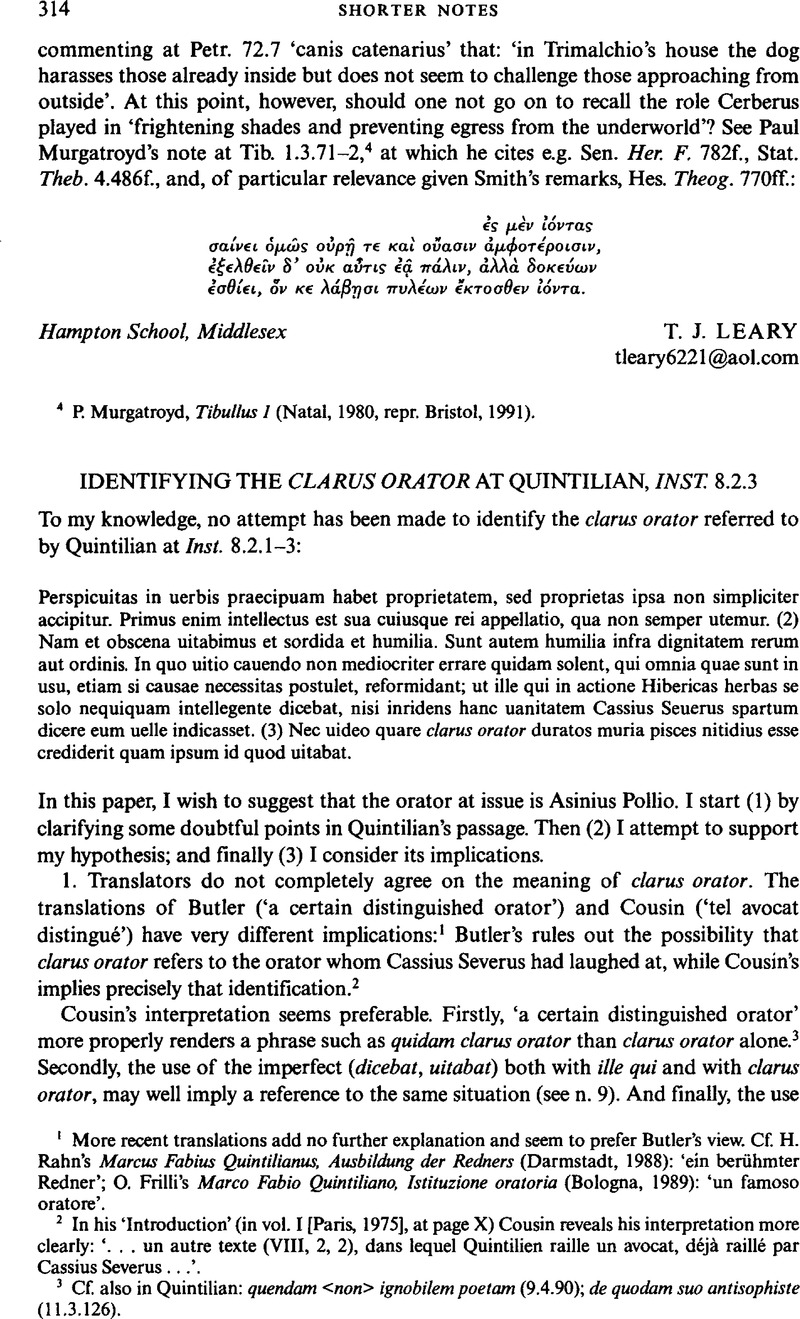

1 More recent translations add no further explanation and seem to prefer Butler's view. Rahn's, Cf. H.Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, Ausbildung der Redners (Darmstadt, 1988)Google Scholar: ‘ein berühmter Redner’; Frilli's, O.Marco Fabio Quintiliano, Istituzione oratorio (Bologna, 1989)Google Scholar: ‘un famoso oratore’.

2 In his ‘Introduction’ (in vol. I [Paris, 1975], at page X) Cousin reveals his interpretation more clearly: ‘… un autre texte (VIII, 2, 2), dans lequel Quintilien raille un avocat, deja raille par Cassius Severus…’.

3 Cf. also in Quintilian: quendam <nori> ignobilem poelam (9.4.90); de quodam suo antisophiste (11.3.126).

4 The combination of clarus and orator is not common at all. A combined search in PHI 5.3 provides only five examples: Cic. Brut. 330.1 post Hortensi clarissimi oratoris mortem; Cic. Oral. 6.4 multi oratores magni et clari fuerunt …; Quint. Inst. 5.13.60 clarissimos oratores; 8.2.3 (our passage); Val. Max. 9.2.2 clarissimique et ciuis et oratoris. It is evidently not a standard forensic formula of the same type as e.g. ‘my learned friend’ in English.

5 This criticism is not surprising at all coming from an orator who cast aside modesty of language, according to Tac. Dial. 26.5… omissa modestia acpudore uerborum… nonpugnat sed rixatur. Cf. M. Winterbottom, ‘Quintilian and the vir bonus’, JRS 54 (1964), 90–7.

6 That is to say ‘a legal process, action, suit’ (OLD s.v. actio); cf. ThLL 1441.48ff.

7 Quint. Inst. 10.1.22… nosse eas causas quorum orationes in manus sumpserimus, et, quotiens continget, utrimque habitas legere actiones: ut Demosthenis et Aeschinis…, et Serui Sulpici atque Messalae…, et Pollionis et Cassi reo Asprenate, aliasqueplurimas.

8 The works by Cassius Severus had a very hazardous history; cf. Tac. Ann. 1.72.4, Suet. Cal. 16.1–2 and see further Gil, L., Censura en el mundo antiguo (Madrid, 1985 2), 139–40 and 152.Google Scholar

9 Both dicebat and uitabat seem to be examples of the so-called ‘aoristisches Imperfekt’ appearing in cases ‘wo der Sprechende aus seiner Erinnerung erzählt oder sich an die Erìnnerung des Hörenden wendet’ (Hofmann-Szantyr, 317, §177). Since it is not possible to assume an actual memory of an actio held long before Quintilian's time, one may argue that Quintilian is relying on his reading of it.

10 Cf. Malcovati, H., Oratorum Romanorumfragmenta liberae reipublicae (Turin, 1955), 523–4Google Scholar; André, J., La Vie et l'æuvre d' Asinius Pollion (Paris, 1949), 72–3Google Scholar; Heldmann, K., Antilce Theorien über Entwicklung und Verfall der Redekunst (Munich, 1982), 165–6.Google Scholar

11 It is the food known as garum (later as liquameri) or, more generally, as salsamenta. Heldmann (n. 10) at 169 thinks that the poisoning was from fish, though this is not in the ancient sources, and he is probably relying on Groag, RE XVII 867.

12 Plin. N.H. 32.45 Sunt et seruatis piscibus medicinae, salsamentorumque cibus prodest a serpente percussis et contra bestiarwn ictus mem subinde hausto ita, ut per satiem cibus uomitione reddatur…

13 Cf. Hor. 5at. 1.10.85 and most significantly Carm. 2.1 (on which see Nisbet-Hubbard, A Commentary on Horace: Odes. Book II [Oxford, 1978], 7 ff.). The book of the Epodes was completed by 30 B.C., so it was surely well known to Pollio at the time of the Asprenas process.

14 Cf. Andrá, J., Les Noms deplantes dans la Rome antique (Paris, 1985)Google Scholar, and Plin. N.H. 24.65.

15 Cf. Cousin (n. 2) at XL, following Austin, R. G., Quintiliani Institutionis oratoriae liber XII (Oxford, 1948), XII–XIII.Google Scholar

16 This has been recently shown by Núnez González, J. M., ‘Censuras de Quintiliano a la doctrina retórica (de numero oratorio) de Cicerón’, CFCLat 15 (1998), 259–71.Google Scholar