Introduction

Clinicians often struggle with managing a multitude of issues that arise in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) including increased anxiety, stress, depression, and sleep problems; difficulty swallowing and unwillingness to eat; as well as issues with medicating (eg, self-medicating, not medicating, or over-medicating). ADHD often presents not in a vacuum, but instead as part of a complex spectrum of emotional, physical, and sociologic conditions. As physicians, we see these complicated cases daily. For example, we may attend to a child with autism and ADHD whose cognitive abilities are improved with medication but has difficulty swallowing a pill; a teenager with ADHD and depression who feels that his medicine helps but causes unwanted mood-related side effects; a mother who presents to her primary care physician feeling overwhelmed and anxious but forgets to mention that her son was recently diagnosed with ADHD and that she has always struggled with similar symptoms; and a dad who drinks and smokes to try to self-medicate his symptoms.

Further complicating the issue of treatment are the natural change of ADHD symptoms over time, the different manifestations of symptoms based on the environmental context, and evolving comorbidities. Children with ADHD typically present with a constellation of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms within the context of external structures such as preschool, school, parental involvement, or other caretaking figures.Reference Curchack-Lichtin, Chacko and Halperin 1 , Reference Willcutt 2 Adolescents transition into a period of increasing cognitive demands with longer duration of daily activities, increased self-autonomy, and decreased external structure, which requires an ability to modulate and self-regulate behaviors and activities.Reference Turgay, Goodman and Asherson 3 During early adulthood, there are increased demands for self-modulation of symptoms combined with a more independent lifestyle and the need to form positive interpersonal relationships.Reference Turgay, Goodman and Asherson 3 Coexisting oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder are highly prevalent in children with ADHD, 4–6 while coexisting conditions are more diverse in adults. 7 , Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8

For patients with ADHD, inattentive and/or hyperactive/impulsive behaviors impair activities of daily living including social interactions, relationships, and school, as well as occupational and financial performances. 6 The presence of comorbid conditions exacerbates underlying functional impairments due to ADHD and tends to worsen long-term functional impairments.Reference Armstrong, Lycett, Hiscock, Care and Sciberras 9 , Reference Safren, Sprich, Cooper-Vince, Knouse and Lerner 10 Treatment plans for ADHD need to be individualized to the patient at different stages of life to alleviate the impairment caused by the changing ADHD presentation, life situations, and comorbidities that may introduce additional challenges. A combination of interventions—or multimodal approach—is recommended for most patients to improve the core symptoms of ADHD and overall quality of life, and includes psychosocial and pharmacological options. 7 , 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12

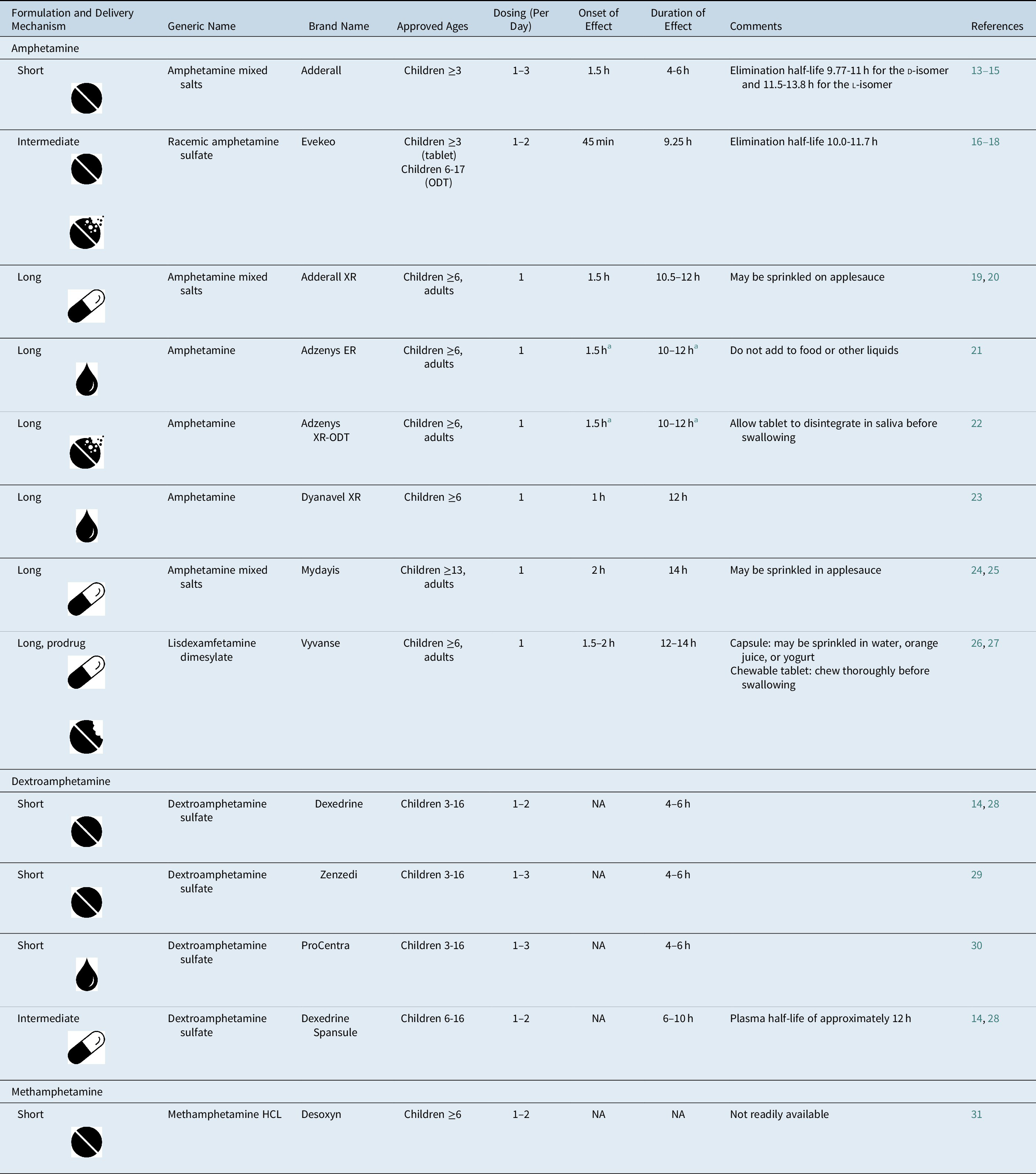

Given the unique situation for each patient and the shifting ADHD presentation over time, clinicians need to be knowledgeable about all available treatment options. In the United States, there are more than 30 approved medications that are mainly comprised of stimulant formulations providing different delivery mechanisms and durations of effect (Tables 1–3). Many clinicians learn of the basic ADHD medication formulations during training, but they rarely touch on the wider array of delivery systems until after training is complete. This review incorporates peer-reviewed studies and the expert experience of the authors to discuss treatment considerations and pharmacological options for patients with ADHD at each stage of life and for those with common co-occurring conditions.

Table 1. FDA-Approved Amphetamine Formulations for ADHD.

Note:  , tablet;

, tablet;  , capsule;

, capsule;  , liquid;

, liquid;  , chewable tablet;

, chewable tablet;  , orally disintegrating tablet.

, orally disintegrating tablet.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HCL, hydrochloride; NA, not available; ODT, orally disintegrating tablet.

a Adzenys XR-ODT and Adzenys ER are bioequivalent to extended-release mixed amphetamine salts (ie, Adderall XR),Reference Stark, Engelking, McMahen and Sikes 32 , Reference Sikes, Stark, McMahen and Engelking 33 but have not been tested independently in a classroom study.

Table 2. FDA-Approved Methylphenidate Formulations for ADHD.

Note:  , tablet;

, tablet;  , capsule;

, capsule;  , liquid;

, liquid;  , chewable tablet;

, chewable tablet;  , orally disintegrating tablet;

, orally disintegrating tablet;  , transdermal patch.

, transdermal patch.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HCL, hydrochloride; NA, not available; ODT, orally disintegrating tablet.

a AAP recommends utilizing methylphenidate as a first choice for preschool aged children.Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12

b Methylin is bioequivalent to Ritalin, 69 but it has not been tested independently in a classroom study.

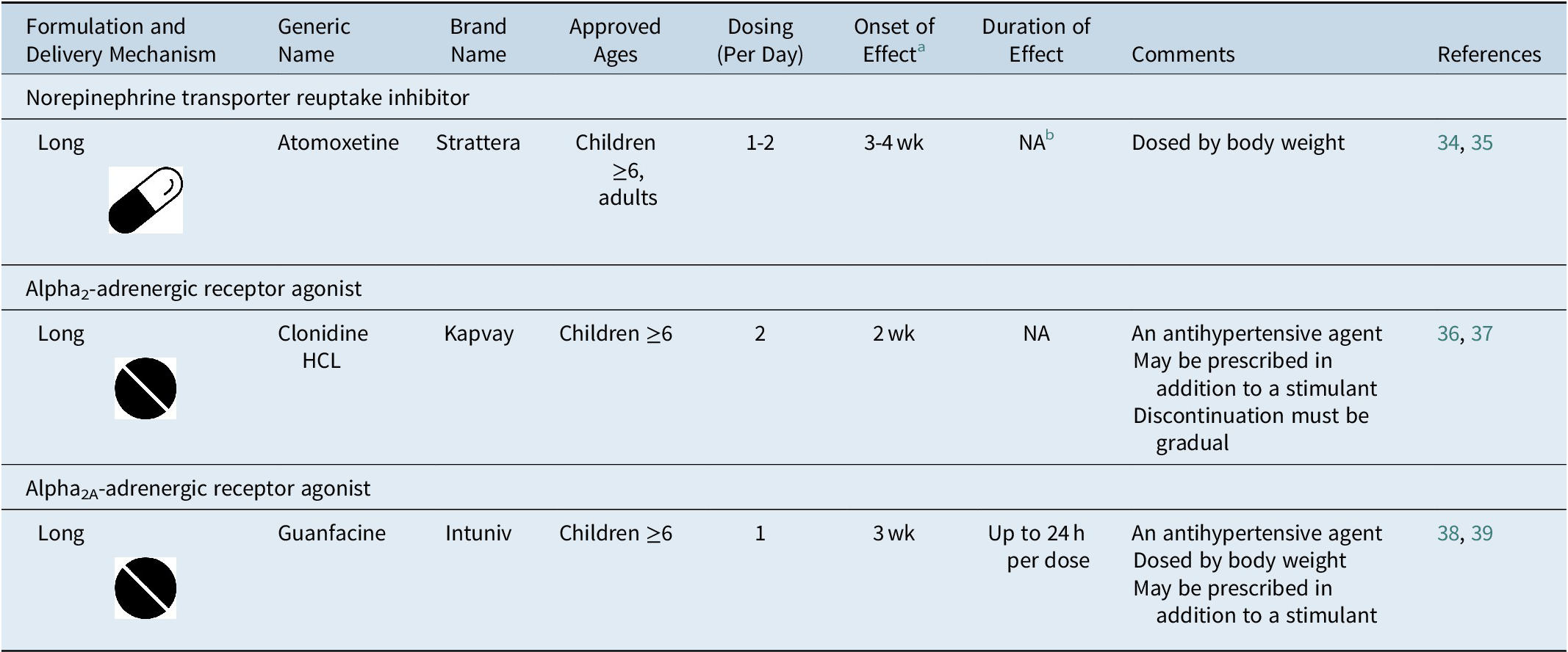

Table 3. FDA-Approved Nonstimulant Medications for ADHD

Note:  , tablet;

, tablet;  , capsule.

, capsule.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HCL, hydrochloride; NA, not available.

a Time to onset of the full effect of nonstimulant medications is extended compared to stimulant medications due to long titration periods.Reference Dickson, Maki, Gibbins, Gutkin, Turgay and Weiss 34 , Reference Jain, Segal, Kollins and Khayrallah 36 , Reference Biederman, Melmed and Patel 38

b The duration of effect of atomoxetine has not been formally measured as in studies of stimulant medications. Evidence from clinical studies suggests that once-daily dosing of atomoxetine is associated with efficacy into the evening.Reference Michelson, Allen and Busner 40

Treatment Reduces the Risk of Morbidity and Mortality and Increases the Quality of Life of Individuals with ADHD

ADHD is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood and will persist into adulthood for many patients. 6 , Reference Sibley, Mitchell and Becker 41 It is associated with significant morbidity,Reference Dalsgaard, Leckman, Mortensen, Nielsen and Simonsen 42 , Reference Hodgkins, Montejano, Sasane and Huse 43 lower quality of life,Reference Agarwal, Goldenberg, Perry and IsHak 44 , Reference Lee, Yang and Chen 45 and increased mortalityReference Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen 46 in all age groups compared with the non-ADHD population. In a large study of the Danish national population, the mortality rate increased by 86% in preschoolers, 58% in children, and 325% in adults over those without ADHD.Reference Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen 46 Furthermore, the risk of death increases in adults with ADHD and a co-occurring psychiatric disorder vs those without another psychiatric disorder (hazard ratio of ~5).Reference Sun, Kuja-Halkola and Faraone 47 On the whole, people with ADHD will experience poorer long-term functional outcomes compared with those who do not have ADHD.Reference Shaw, Hodgkins and Caci 48 ADHD in childhood contributes to worse academic performance, lower rates of high school graduation, and lack of higher degrees. 49–51 Occupational outcomes are also negatively affected by ADHD, with higher rates of unemployment, frequent job switching, and overall financial problems. 49–51 ADHD also affects a person’s social life, causing higher rates of divorce and separation, as well as issues with interpersonal relationships. 49–51 Impulsive risk-seeking behaviors exhibited by individuals with ADHD contribute to a greater likelihood of teenage pregnancy,Reference Barkley, Fischer, Smallish and Fletcher 50 criminal behavior, 52–54 and substance abuse.Reference Kaye, Gilsenan and Young 55 , Reference Levy, Katusic and Colligan 56

Treatment can lower these risks, sometimes to levels similar to control populations. Pharmacotherapy has been shown to improve executive function, reduce risk-seeking behavior, and decrease rates of criminality in individuals with ADHD.Reference Lichtenstein, Halldner and Zetterqvist 53 , Reference Mohr-Jensen, Muller Bisgaard, Boldsen and Steinhausen 54 , 57–59 ADHD treatment has also been shown to decrease trauma rates with dramatic reduction in motor vehicle trauma,Reference Dalsgaard, Leckman, Mortensen, Nielsen and Simonsen 42 , Reference Chang, Quinn and Hur 60 and it can decrease the risk of substance use-related disorders.Reference Wilens, Adamson and Monuteaux 59 , Reference Uchida, Spencer, Faraone and Biederman 61 A 2012 meta-analysis of long-term outcomes of ADHD treatment found 50% to 100% improvement in driving, obesity, self-esteem, social functioning, academics, drug use/addiction, antisocial behaviors, and use of services for treated vs untreated patients.Reference Shaw, Hodgkins and Caci 48 Moreover, treatment with stimulants in childhood provides protective effects against risks for disruptive mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders, academic failure, and car accidents.Reference Biederman, DiSalvo, Fried, Woodworth, Biederman and Faraone 62 Biederman et al found that one in every three patients with ADHD treated with stimulants were prevented from repeating a grade or developing certain comorbid disorders, and one in four were protected against developing major depressive disorder or having a car accident.Reference Biederman, DiSalvo, Fried, Woodworth, Biederman and Faraone 62 It is critical to treat ADHD early and effectively to minimize harm and increase a patient’s quality of life.Reference Dalsgaard, Leckman, Mortensen, Nielsen and Simonsen 42 , Reference Agarwal, Goldenberg, Perry and IsHak 44 , Reference Coghill, Banaschewski, Soutullo, Cottingham and Zuddas 63

It is also important to note that pharmacotherapy is just one component of an ADHD treatment plan. For instance, in preschool-aged children with ADHD, the recommended first line of treatment is behavioral therapy and methylphenidate should be prescribed only if the behavioral interventions do not provide sufficient improvement and moderate-to-severe disturbances continue to affect the child’s function.Reference Wolraich 64 Similarly, clinicians should help create long-term comprehensive plans for patients with ADHD that focus on identifying and addressing individualized and specific behavioral, academic, and/or social target goals.Reference Wolraich 64 In the comprehensive Mental Health Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD, the combination of behavioral therapy and medication was superior to medication alone for treatment of oppositional/aggressive symptoms in individuals with ADHD. 65 Treatment success may be greatly improved by clinicians encouraging patients to build environmental support systems, and to incorporate behavioral therapy as well as pharmacotherapy into their treatment plan.

Pharmacotherapy for ADHD

Medications approved to treat ADHD include stimulants (amphetamine and methylphenidate; Tables 1 and 2) and nonstimulants (atomoxetine, guanfacine, and clonidine; Table 3). Stimulants are the first-line pharmacological treatment for both children and adults because they show greater efficacy, while currently available nonstimulants are often used when a patient is unresponsive to or cannot tolerate stimulants. 7 , 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 , Reference Bolea-Alamanac, Nutt and Adamou 85 , Reference Kooij, Bijlenga and Salerno 86 Importantly, interpatient response to each medication class is variable, and the response to one class does not predict response to another.Reference Ramtvedt, Roinas, Aabech and Sundet 87 If a patient has a suboptimal response to one class of ADHD stimulant, then a trial with another medication class should be initiated to optimize patient outcomes. In our practice, we also find that a patient may respond poorly to one stimulant delivery system, while another delivery mechanism of the same medication class may illicit a better response in regard to symptom reduction, smoothness or duration of effect, or tolerability.

Various medication delivery technologies have been developed to address individual patient needs (Tables 1 and 2). These technologies can provide a nonoral route of administration—as with the methylphenidate transdermal patch (Daytrana) 79—or extend the release of the drug over the course of the day, allowing for once-daily dosing.Reference Shargel, Wu-Pong and Yu 88 Extended-release technologies include capsules containing immediate-release beads and beads with a pH-dependent coating for drug release upon entry into different sections of the intestinal tract (eg, Adderall XR, 19 Adhansia XR, 82 Aptensio XR, 89 and MyDayis 24); a methylphenidate osmotic release capsule (Concerta) 78; an amphetamine prodrug, lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (eg, Vyvanse), 26 where a biological enzymatic reaction is required to release active amphetamine 26 , Reference Pennick 90; and ion-exchange microparticles containing immediate-release and extended-release medication (eg, Adzenys XR-ODT, 22 Cotempla XR-ODT, 91 and Dyanavel XR 23).

Duration and onset of effect for the various medications should be considered for individualization. Short-acting formulations last for 3 to 6 hours and require multiple dosing per day. Conversely, a single dose of a long-acting formulation provides relief of ADHD symptoms from 8 to 16 hours, depending on the delivery system. Long-acting ADHD medications are associated with better adherence than short-acting medicationsReference Christensen, Sasane, Hodgkins, Harley and Tetali 92 and may reduce medication-related social stigma. 11 Onset of effect should also be considered. For the patient with early morning issues, a short acting stimulant can be prescribed for immediate relief followed by a long-acting formulation. Alternatively, the recently approved Jornay PM is taken at bedtime with the onset of effect delayed for 8 to 10 hours to allow the drug to be delivered in the early morning.Reference Childress, Mehrotra, Gobburu, McLean, DeSousa and Incledon 80 Nonstimulants can be taken once or twice daily, but often require several weeks to show a maximum treatment effect.Reference Dickson, Maki, Gibbins, Gutkin, Turgay and Weiss 34 , Reference Jain, Segal, Kollins and Khayrallah 36 , Reference Biederman, Melmed and Patel 38

Difficulty swallowing is another consideration when choosing an ADHD medication. While this is generally considered a problem for young children,Reference Beck, Cataldo, Slifer, Pulbrook and Guhman 93 it can also occur for adolescents and adults.Reference Lau, Steadman, Mak, Cichero and Nissen 94 , Reference Wagner, Markowitz and Patrick 95 Many tablets and capsules cannot be crushed or chewed, although the bioavailability of some capsules has been systematically studied when sprinkled into specific kinds of food and drink (Tables 1 and 2). Clinicians should determine whether this is an issue for individual patients so they can advise on pill swallowing techniques and aidsReference Schiele, Schneider, Quinzler, Reich and Haefeli 96 , Reference Patel, Jacobsen, Jhaveri and Bradford 97 or prescribe a liquid, chewable, orally disintegrating tablet, or transdermal formulation (Tables 1 and 2). Nonstimulants are currently not available in alternative delivery forms and they must be swallowed whole (Table 3).

ADHD medications are associated with a range of adverse effects, although most are mild and temporary. 7 Patients on stimulants may frequently present with decreased appetite, sleeping issues, abdominal pain, or nausea/vomiting while on stimulant therapy.Reference Punja, Shamseer and Hartling 98 , Reference Epstein, Patsopoulos and Weiser 99 For adults, increased heart rate and blood pressure may be more common with stimulant treatment.Reference Mick, McManus and Goldberg 100 Common atomoxetine-associated adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms, anorexia, fatigue, and weight loss.Reference Schwartz and Correll 101 Clonidine and guanfacine are both associated with sedation, somnolence, and fatigue and may decrease blood pressure in rare cases.Reference Hirota, Schwartz and Correll 102 , Reference Ruggiero, Clavenna, Reale, Capuano, Rossi and Bonati 103 While serious cardiac complications are uncommon occurrences with both stimulants and nonstimulants,Reference Hennissen, Bakker and Banaschewski 104 , Reference Cooper, Habel and Sox 105 these medications should be prescribed with caution in patients with known cardiac defects. Stimulant pharmacotherapy also slows the growth of children with ADHD (height and weight)Reference Powell, Frydenberg and Thomsen 106 , Reference Swanson, Greenhill and Wigal 107; however, ADHD treatment was not associated with differences in final adult height in a longitudinal study.Reference Harstad, Weaver and Katusic 108

Patient engagement with ADHD pharmacotherapy is another important issue. Patient engagement and adherence to stimulant medication is often low, likely due to many factors including the complexity of renewing a schedule II medication, poor tolerability to stimulants, as well as misinformation, biases, or uncertainty about the use of stimulants to treat ADHD.Reference Biederman, Fried and DiSalvo 109 In a recent study, stimulant prescription renewal was significantly increased when a novel text messaging intervention platform was implemented vs treatment as usual.Reference Biederman, Fried and DiSalvo 109 As the world becomes more digitized, innovative technological solutions for traditional compliance or engagement challenges should be used to support individuals with ADHD to easily access and fill prescriptions for their medications.

Prescribing ADHD Medication by Age

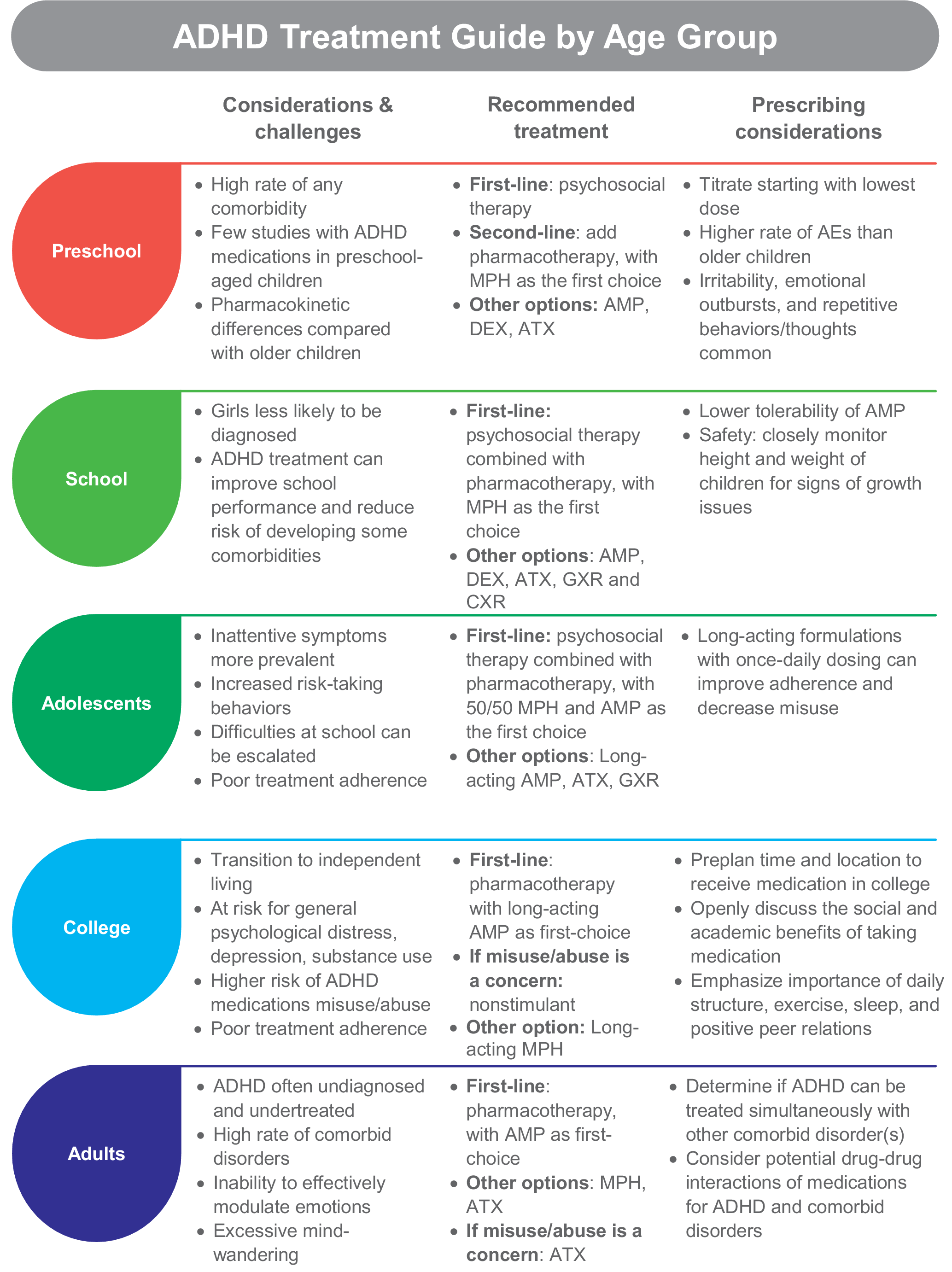

The challenges, considerations, and recommended treatments for each age group are described below and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ADHD treatment guide by age group. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AE, adverse event; AMP, amphetamine; ATX, atomoxetine; DEX, dextroamphetamine; GXR, guanfacine extended release; MPH, methylphenidate.

Preschool

In 2016, 2.1% of U.S. children aged 2 to 5 years were diagnosed with ADHDReference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110 and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is now requiring new ADHD medications to conduct preschool studies. 111 Dramatic hyperactivity/impulsivity is the overt presentation in this group.Reference Curchack-Lichtin, Chacko and Halperin 1 However, these behaviors can be caused by other factors, which is why a comprehensive examination for ADHD is needed before beginning treatment.Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) suggests that ADHD can be accurately diagnosed in children beginning at 4 years of age,Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 although children as young as 2 years have been diagnosed.Reference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110 Preschoolers with subthreshold ADHD should also be monitored closely since up to one-third are likely to progress to a full diagnosis of ADHD or other mental health problems.Reference Smith, Meyer and Koerting 112

The recommended first-line treatment for children under the age of 6 is psychosocial intervention, which can include parent training, behavioral therapy, or cognitive training. 7 , 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 Psychosocial treatments improve ADHD symptoms for this group, with an effect size of 0.75 in favor of intervention.Reference Charach, Carson, Fox, Ali, Beckett and Lim 113 Adding pharmacotherapy to the treatment plan is recommended when very young patients with moderate-to-severe ADHD do not improve with psychosocial therapies alone. 7 , 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 Accordingly, in 2016, preschool-aged U.S. children with ADHD were most commonly receiving behavioral treatment (45.8%) or no treatment (36.0%) more often than treatment with medication alone (4.5%) or medication combined with behavioral therapy (13.7%).Reference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110

There are five FDA-approved medications for ADHD in children 3 to 5 years of age and all are short-acting amphetamine formulations (Table 1). They include a liquid and tablet form of dextroamphetamine, a tablet for mixed amphetamine salts, and a tablet and chewable form of racemic amphetamine sulfate. While methylphenidate has not been approved for use in this age group, the AAP suggests prescribing a methylphenidate as the first-choice pharmacotherapy because there are more robust clinical studies of methylphenidate than amphetamine in preschool children.Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 Short-acting methylphenidate administered three times a day improved ADHD symptoms and impairment in preschoolers in Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS).Reference Greenhill, Kollins and Abikoff 114 A recent study demonstrated the safety and efficacy of an extended-release methylphenidate formulation (Aptensio XR) for preschoolers with ADHD.Reference Childress, Kollins and Adjei 115 In case reports, the methylphenidate transdermal system provided improvement in ADHD symptoms for preschoolers.Reference Ghuman, Byreddy and Ghuman 116 Atomoxetine reduced ADHD symptoms by at least 30% for 75% of preschoolers in a small open-label study (mean daily dose of 1.59 mg/kg).Reference Ghuman, Aman and Ghuman 117

Special prescribing considerations for preschool-aged children include pharmacokinetic (PK) differences, number of comorbidities, and a higher rate of adverse effects when compared with school-aged children. Differences in drug metabolism, elimination, and gastrointestinal function between preschoolers and older children or adults may affect drug PK,Reference Kearns, Abdel-Rahman, Alander, Blowey, Leeder and Kauffman 118 and few PK studies of ADHD medications in preschool-aged children are available. In PATS, preschool children metabolized short-acting methylphenidate at a slower rate, which increased overall drug exposure as compared with older children.Reference Wigal, Gupta and Greenhill 119 Clinicians experienced with prescribing stimulant therapy to preschool-aged children recommend that while long-acting medications help with both preschool and home activities, there are occasions when a short-acting medication may be appropriate. For example, to cover only a half-day of preschool or to test for adverse effects of a medication before transitioning to a long-acting formulation. Nonetheless, as a general rule for this group, titration should be initiated at a low dose with small increments over an extended period of time.

Comorbid disorders are common in preschool-aged children. About 70% of participants in PATSReference Posner, Melvin and Murray 120 and 93% of those in a large Spanish studyReference Canals, Morales-Hidalgo, Jane and Domenech 121 had at least one co-occurring disorder, and 57.6% of children in the Spanish study had three or more disorders in addition to ADHD. Importantly, the number of co-occurring disorders in PATS participants inversely affected the efficacy of methylphenidate treatment (effect size decreased with increasing number of comorbidities).Reference Ghuman, Riddle and Vitiello 122 Oppositional defiant disorder occurs in about one-half of preschoolers with ADHDReference Posner, Melvin and Murray 120 , Reference Canals, Morales-Hidalgo, Jane and Domenech 121; behavioral strategies may lessen parent–child conflict, potentially contributing to a more effective treatment of ADHD symptomatology. Other frequent comorbid disorders include communication-related issues, anxiety, tics, and obsessive–compulsive problems.Reference Posner, Melvin and Murray 120 , Reference Canals, Morales-Hidalgo, Jane and Domenech 121 General prescribing recommendations for some common comorbid disorders are discussed in the next section.

Clinicians should be aware that stimulants may produce a somewhat different adverse event profile in preschoolers than older children. Decreased appetite, delay of sleep onset, headaches, and stomachaches were the top adverse effects related to methylphenidate for school-aged children,Reference Barkley, McMurray, Edelbrock and Robbins 123 whereas preschool children taking methylphenidate experienced irritability, emotional outbursts, and repetitive behaviors/thoughts in addition to decreased appetite and sleep issues.Reference Wigal, Greenhill and Chuang 124 Additionally, there is a higher rate of methylphenidate discontinuation due to adverse events for preschoolers than older children.Reference Wigal, Greenhill and Chuang 124 With atomoxetine, frequent adverse effects related to treatment were gastrointestinal issues, sleep disturbance, irritability, defiance, agitation, and crying/whining.Reference Ghuman, Aman and Ghuman 117

School-aged children

The estimated prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents ranges from 3% to 10.2%, with the highest rates in North America/the United States. 125–127 Most children are diagnosed with ADHD after entry into school,Reference Visser, Zablotsky, Holbrook, Danielson and Bitsko 128 with boys diagnosed at a higher rate than girls.Reference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110 The difference in diagnosis by gender is likely driven by the referrer’s perceptions that the level of ADHD symptoms (ie, frequent lack of overt hyperactivity) may cause less impairment for girls, although studies of nonreferred samples find that ADHD severity, associated comorbidities, and impairment are similar between genders. 129–131 Frequent school age comorbidities include learning disabilities and oppositional defiant disorder, with anxiety, conduct disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and tic disorders being somewhat common. 7 Without intervention, children are more likely to struggle academically, be held back a grade, and are at higher risk for developing comorbid depression, oppositional defiant disorder, and/or conduct disorder.Reference Biederman, Monuteaux, Spencer, Wilens and Faraone 132

Pharmacotherapy should be considered as first-line treatment in conjunction with psychosocial therapy for school-aged children, with stimulants preferred over nonstimulants when possible. 7 , 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 A recent network meta-analysis found that while both types of stimulants are effective at reducing ADHD symptoms, amphetamine was superior to methylphenidate, atomoxetine, and modafinil for symptom improvement in children.Reference Cortese, Adamo and Del Giovane 133 However, due to lower tolerability of amphetamine in this age group, methylphenidate was recommended as the first-choice medication for ADHD. Regarding safety, there are data suggesting that stimulant medication may affect long-term growth (height and weight) of childrenReference Powell, Frydenberg and Thomsen 106 , Reference Harstad, Weaver and Katusic 108; thus, clinicians should closely monitor height and weight. Recent studies show that weight recovery treatments (eg, calorie supplementation, drug holidays, and monthly weight monitoring) may facilitate increased weight gain.Reference Waxmonsky 134

In a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing long- vs short-acting methylphenidate in children (average age 8.25-11.3 years) using both parent and teacher reports on inattention and hyperactivity, no significant differences were found in efficacy and behavior at home or in school between the two methylphenidate formulations.Reference Punja, Zorzela, Hartling, Urichuk and Vohra 135 Additionally, the rate of injuries in children with ADHD was not significantly different in those taking long-acting or short-/medium-acting methylphenidate formulations.Reference Golubchik, Kodesh and Weizman 136 For clinicians considering which duration of action of a medication is appropriate for a school-aged patient, adverse effects and individual needs at different times of day may be of higher importance than how the duration impacts school performance.

Adolescents

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control, about 14% of U.S. teens will have had an ADHD diagnosis at some point.Reference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110 During adolescence, symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity begin to wane while inattentive symptoms usually persist.Reference Holbrook, Cuffe and Cai 137 Risk-taking behaviors increase in this age group,Reference Steinberg, Icenogle and Shulman 138 which can lead to high rates of injuries,Reference Ruiz-Goikoetxea, Cortese and Aznarez-Sanado 139 teenage pregnancy,Reference Ostergaard, Dalsgaard, Faraone, Munk-Olsen and Laursen 140 and driving accidents.Reference Curry, Metzger, Pfeiffer, Elliott, Winston and Power 141 In our practice, we find that difficulties at school are often exacerbated by increased cognitive demands, decreased external structure, and longer days. Adolescents may not adhere to or may discontinue their medicationReference Danielson, Bitsko, Ghandour, Holbrook, Kogan and Blumberg 110 , Reference Gajria, Lu and Sikirica 142 even though it helps prevent risky behaviors and increases academic performance.Reference Chang, Quinn and Hur 60 , Reference Ruiz-Goikoetxea, Cortese and Aznarez-Sanado 139 , Reference Chorniy and Kitashima 143 , Reference Barbaresi, Katusic, Colligan, Weaver and Jacobsen 144 In adolescence, we may also begin to see patients diverting (swapping with or selling to peers) or misusing their short-acting stimulants. Engaging the adolescent patient and parents in shared decision making about ADHD treatment and monitoring for signs of diversion and misuse can help improve medication adherence and enhance outcomes.Reference Charach and Fernandez 145 Educating parents about the importance of their active involvement in the management and delivery of medications to their child, ongoing communication between parent and child with respect to treatment effectiveness, and side effects or concerns are key elements to successful therapy. The adolescent’s opinion should also be considered when making medication recommendations.Reference Charach and Fernandez 145

Stimulants are the recommended first-line treatment for adolescents, with psychosocial therapy also recommended to create a multimodal plan. 11 , Reference Wolraich, Brown and Brown 12 Strategies that involve organization skills, time management, and planning are fundamental, especially at this stage of development. Methylphenidate is the first-choice medication based on combined efficacy and safety information,Reference Cortese, Adamo and Del Giovane 133 although long-acting amphetamines, atomoxetine, and guanfacine are also effective.Reference Chan, Fogler and Hammerness 146 Use of long-acting formulations with once-daily dosing improves adherence and they are less likely to be misused or diverted.Reference Christensen, Sasane, Hodgkins, Harley and Tetali 92 , Reference Wilens, Gignac, Swezey, Monuteaux and Biederman 147 , Reference Wilens, Zulauf and Martelon 148

College-aged young adults

The challenge of adjusting to independent living with more responsibilities is particularly difficult for people with ADHD. College students with ADHD experience higher rates of depression, substance use, and general psychological distress. 149–151 Misuse of ADHD medications is nearly five times more likely among college students with ADHD than without.Reference Benson, Flory, Humphreys and Lee 152 ADHD symptoms continue to affect academic performance and contribute to higher levels of stress in college students with ADHD as compared with unaffected students.Reference Blase, Gilbert and Anastopoulos 149 Stimulants can help to reduce symptoms of ADHD in this age groupReference Dupaul, Weyandt and Rossi 153; however, clinicians should monitor for misuse and abuse of ADHD medications as well as for problems with illicit substances. If the patient has a higher risk for misuse/diversion, a nonstimulant may be prescribed.

The transition from pediatric to adult healthcare is another critical feature of this time; many students will display poor treatment adherence. Several models of transitional care are available and can increase the rate of continued treatment in the college-age population.Reference Kooij, Bijlenga and Salerno 86 , Reference Fogler, Burke, Lynch, Barbaresi and Chan 154 In our experience, preplanning with high school seniors on where and how they will receive their ADHD medication (ie, sent to their college pharmacy, mailed from their parents, prescribed by their student health system) is beneficial. Daily use of ADHD treatment is improved with once-daily medications and when there is an honest and open dialogue about where treatment makes a difference in their lives. The importance of daily structure, exercise, sleep, and positive peer relations should all be discussed as important areas for successfully coping with ADHD in the college years.

Adults

Prevalence of adult ADHD is estimated at 2.8% globallyReference Fayyad, Sampson and Hwang 155 and 4.4% in the United States.Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8 However, adult ADHD is underdiagnosed because it is often mistaken for other disorders and its symptoms may abate with age or be masked through the development of coping mechanisms.Reference Ginsberg, Quintero, Anand, Casillas and Upadhyaya 156 , Reference Barkley and Brown 157 Comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception for adult ADHD; greater than 50% of patients will have one comorbid disorder and about one in seven will have three or more co-occurring disorders.Reference Fayyad, Sampson and Hwang 155 Furthermore, adults with ADHD may have sleep problems, an inability to effectively modulate emotions, and excessive mind-wandering.Reference Asherson, Buitelaar, Faraone and Rohde 158 ADHD is undertreated in adults—with only 11% receiving ADHD treatment in the past 12 months, according to a U.S. survey.Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8

Pharmacotherapy is the recommended first-line treatment for ADHD. 11 , Reference Kooij, Bijlenga and Salerno 86 Based on a network analysis evaluating both efficacy and safety of multiple ADHD medications, amphetamine-based medication is recommended over methylphenidate as the first-choice stimulant for adults.Reference Cortese, Adamo and Del Giovane 133 Regarding safety, CNS stimulant medications are associated with stroke, myocardial infarction and sudden death, increased blood pressure (2-4 mmHg), and increased heart rate (3-6 bpm). 22 Therefore, patients should be routinely evaluated during treatment if they develop chest pain upon exertion, syncope, or arrhythmias. 22

Atomoxetine has also shown efficacy in adults; however, due to the lower effect size, it is considered an option for patients at risk for substance use disorder (SUD) or who cannot tolerate stimulant formulations. 7 , 11 , Reference Kooij, Bijlenga and Salerno 86 Guanfacine and clonidine are not approved for use in adults, and few trials in this age group have been performed. A double-blind, placebo controlled study comparing guanfacine to dextroamphetamine for the treatment of ADHD in adults found guanfacine and dextroamphetamine reduced ADHD symptoms on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) Adult Behavior Checklist for Adults to a similar extent vs placebo (P < .05) and guanfacine was well tolerated.Reference Taylor and Russo 159 In our experience, guanfacine use in an adult may be useful if the patient responded to this treatment in childhood.

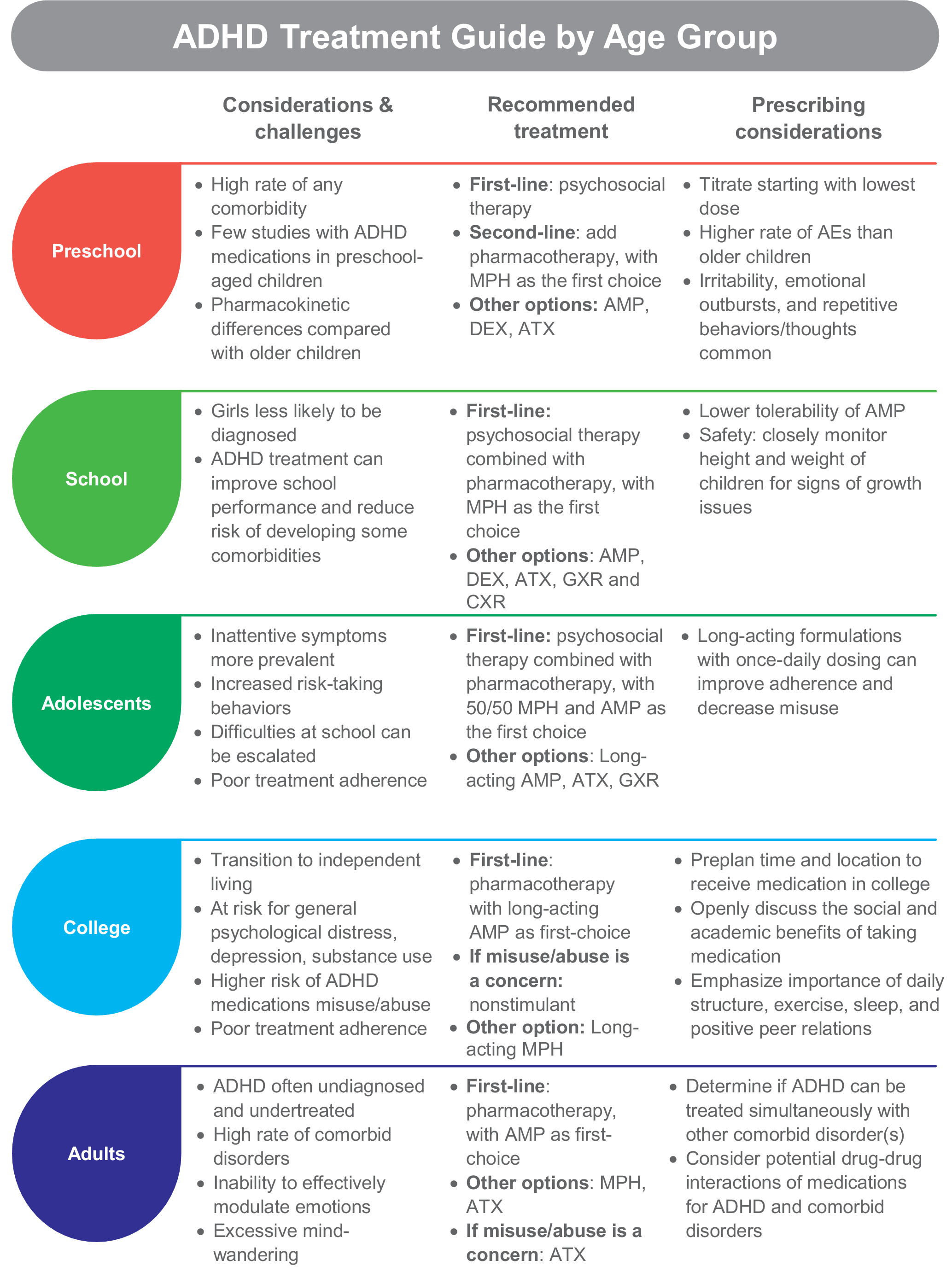

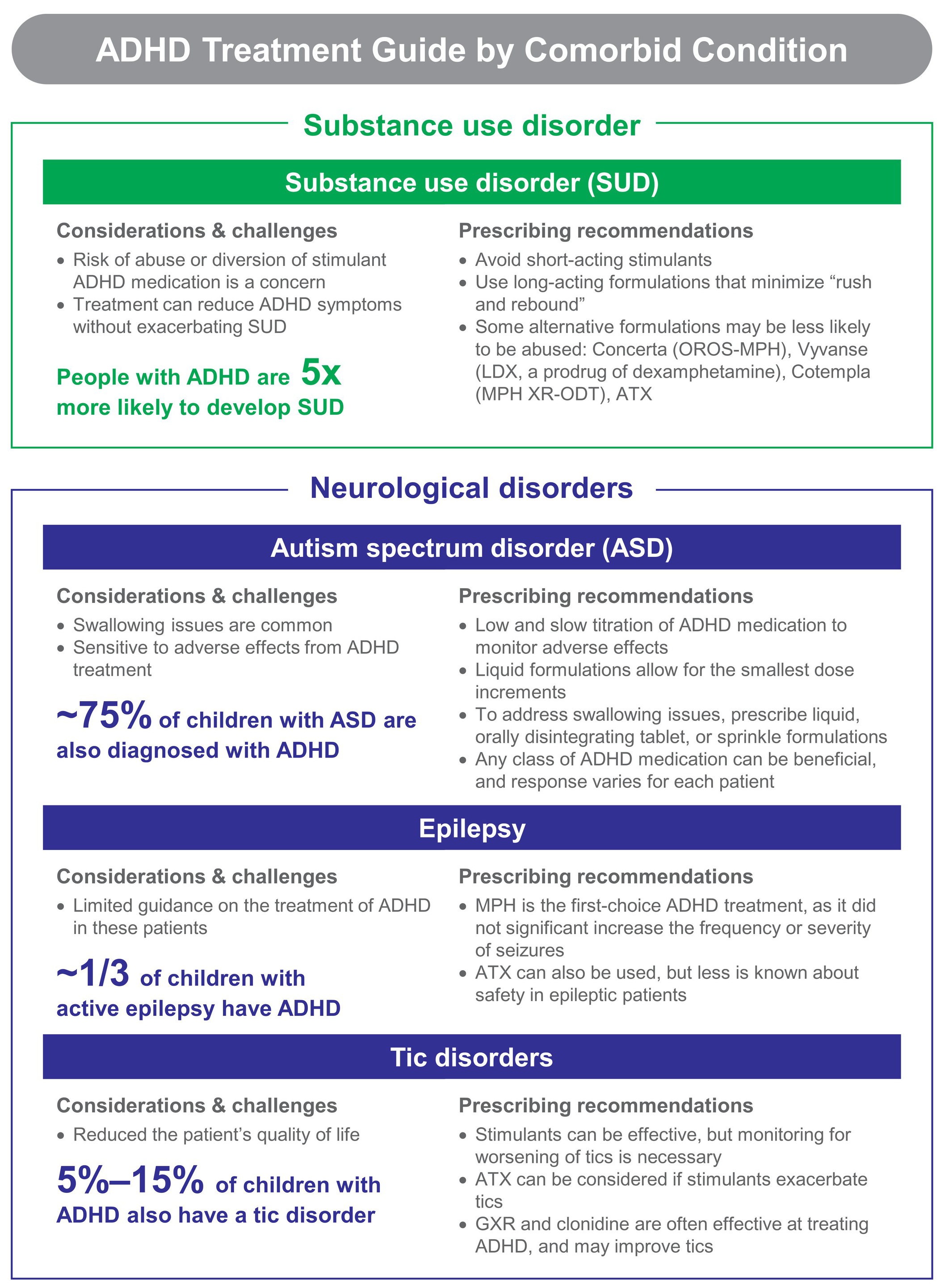

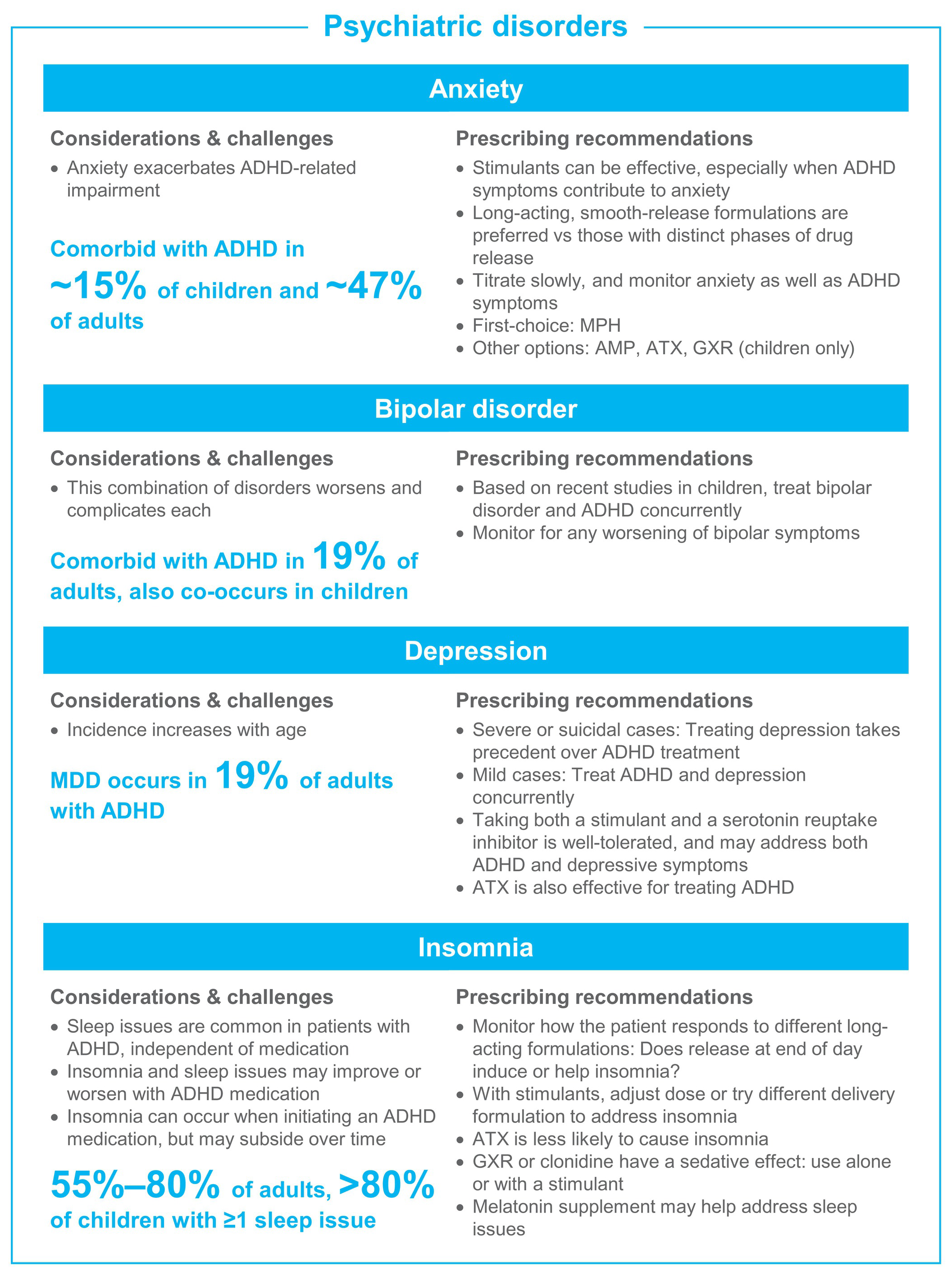

Prescribing ADHD Medication for Patients with Common Co-Occurring Disorders

Treatment becomes more complicated when patients present with ADHD and comorbid conditions. Clinicians must determine if ADHD can be treated simultaneously with the other disorder(s), and if not, the most severe disorder should be treated first. Although not reviewed in-depth here, potential drug-drug interactions of medications for ADHD and comorbid disorders are a critical consideration (eg, the interaction of atomoxetine—a potent 2D6 inhibitor—with paroxetine—a 2D6 substrate—where the addition of paroxetine led to increased plasma atomoxetine concentrations, and increased standing and orthostatic heart rate compared with monotherapy).Reference Belle, Ernest, Sauer, Smith, Thomasson and Witcher 160 Figure 2 presents an overview of the challenges, considerations, and prescribing recommendations.

Figure 2. ADHD treatment guide by comorbid condition. Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AMP, amphetamine; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ATX, atomoxetine; GXR, guanfacine extended release; LDX, lisdexamfetamine dimesylate; MDD, major depressive disorder; MPH, methylphenidate; OROS, osmotic controlled release oral delivery system; OTD, orally disintegrating tablet; SUD, substance use disorder.

Substance use disorder

SUD is a serious condition that emerges as a coexisting disorder in ADHD adolescents with rates increasing into adulthood.Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8 , Reference van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, van de Glind and Koeter 161 ADHD is a risk factor for use disorder of several substances including alcohol, marijuana, psychoactive substances, and nicotine.Reference Charach, Yeung, Climans and Lillie 162 Patients with ADHD are likely to develop SUD earlier than their peers, and experience a faster transition to a higher severity of addiction.Reference Fatseas, Hurmic and Serre 163 Individuals whose ADHD persists from childhood into the young adult years may be five times more likely to develop SUD, whereas those with remittent ADHD are similar to the healthy population.Reference Ilbegi, Groenman and Schellekens 164 The presence of additional co-occurring disorders often occurs in patients with ADHD and SUD.Reference van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, van de Glind and Koeter 161

Past concerns that stimulant treatment in childhood facilitates the later development of SUDs were dispelled by two meta-analyses. Schoenfelder et al revealed that treatment of childhood ADHD with stimulants was associated with lower rates of future smoking compared with no treatment.Reference Schoenfelder, Faraone and Kollins 165 Humphreys et al evaluated 15 longitudinal studies and found no differences in the risk for developing alcohol, cocaine, marijuana, or nonspecific drug use disorders at later ages between stimulant-treated and untreated children with ADHD.Reference Humphreys, Eng and Lee 166

Many clinicians may be wary of prescribing stimulant medication to an ADHD patient with SUD, as there is a well-known higher risk for misuse and diversion.Reference Faraone and Upadhyaya 167 However, treating ADHD should not be avoided outright given the effect ADHD can have on quality of life as discussed in the beginning of this review. Treatment can reduce ADHD symptoms without negative effects on SUD, and there have not been any specific safety issues with medication in this group.Reference Winhusen, Lewis and Riggs 168 We recommend avoiding short-acting stimulants and to prescribe long-acting formulations that minimize “rush and rebound.”

In patients with ADHD and a specific stimulant SUD (such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, or cocaine), there may be a role for stimulants to moderate the SUD similar to the use of buprenorphine or methadone to improve opioid use disorder. One study examined d-amphetamine in managing methamphetamine use disorders and found a decrease, although not statistically significant, in self-administration of methamphetamine during d-amphetamine maintenance therapy.Reference Pike, Stoops, Hays, Glaser and Rush 169 Further research is necessary to determine whether changes in stimulant dosage or route of administration are beneficial for treatment of amphetamine or methamphetamine SUDs in patients with ADHD.

Some delivery technologies further minimize the abuse potential of long-acting stimulants. The osmotic-release oral capsule of Concerta is less likely to be abusedReference Winhusen, Lewis and Riggs 168 and the nondeformable shell minimizes the potential to grind or snort the medication. The prodrug delivery technology of lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) has been shown to have less likability than short-acting amphetamine when taken orallyReference Jasinski and Krishnan 170 or intravenously.Reference Jasinski and Krishnan 171 We are aware of one study assessing the impact of concomitant administration of alcohol on the PKs of a stimulant medication in vivo. The amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet (Adzenys XR-ODT) was studied in conjunction with concomitant alcohol concentrations of up to 40% in healthy adult volunteers. There was no change in the extent of absorption for d - or l -amphetamine and no dose-dumping of the extended release portion of the formulation.Reference Newcorn, Stark, Adcock, McMahen and Sikes 172 Atomoxetine also displays little abuse potential.Reference Upadhyaya, Desaiah and Schuh 173 , Reference Lile, Stoops, Durell, Glaser and Rush 174 Appropriate consideration of ADHD treatment in individuals with comorbid SUD may improve overall outcomes.

Psychiatric disorders: anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, and insomnia

Anxiety

Comorbid anxiety disorders occur in about 15% of children and 47% of adults with ADHD,Reference Elia, Ambrosini and Berrettini 4 , Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8 and they cause greater ADHD-related impairment.Reference Reimherr, Marchant, Gift and Steans 175 Stimulants may be useful in treating ADHD in children and adults with co-occurring anxiety,Reference Reimherr, Marchant, Gift and Steans 175 , Reference Group 176 especially in cases where the ADHD symptoms contribute to anxiety and emotional distress. Although individual responses differ, we find that methylphenidate is less likely than amphetamine to induce anxiety; smooth-release formulations (ie, where both the peak and offset are smooth, such that medication will gradually absorb into the system, rest at peak levels, and gradually decline) also often induce less anxiety. We recommend choosing a stimulant with a smooth-release profile, and to titrate slowly starting with a low dose. Atomoxetine has also been shown to effectively treat ADHD in patients with co-occurring anxiety disorders.Reference Clemow, Bushe, Mancini, Ossipov and Upadhyaya 177 Guanfacine does not exacerbate anxiety in childrenReference Strawn, Compton, Robertson, Albano, Hamdani and Rynn 178 and may be considered if other options are ineffective.

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a frequently encountered comorbid condition with ADHD, which may be easily missed. In the National Comorbidity Study, 19% of adults with ADHD had comorbid bipolar disorder.Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8 In children with bipolar disorder, coexisting ADHD is fairly common but rates have been highly variable with as few as 4% and as many as 94% in different studies.Reference Frías, Palma and Farriols 179 The combination of the two disorders worsens and complicates each.Reference Frías, Palma and Farriols 179

Historically, it was recommended to treat bipolar symptoms before treating ADHD; however, recent studies indicate that simultaneous treatment can be effective, and possibly beneficial. In a study of adults with bipolar disorder, the risk of a manic episode was increased with methylphenidate treatment alone, whereas manic episode risk was reduced when methylphenidate was taken with a mood stabilizer (aripiprazole, lithium, olanzapine, quetiapine, or valproate).Reference Viktorin, Ryden and Thase 180 In two recent large, double-blind studies of medication for bipolar disorder (one of asenapine, one of lurasidone) in children and adolescents, stimulant use did not alter the effectiveness of the bipolar medication in the subgroup of patients with comorbid ADHD.Reference DelBello, Goldman, Phillips, Deng, Cucchiaro and Loebel 181 , Reference Findling, Landbloom and Szegedi 182

Depression

Major depressive disorder prevalence increases with age,Reference Turgay and Ansari 183 ultimately affecting about 19% of adults with ADHD.Reference Kessler, Adler and Barkley 8 Additionally, young people with ADHD may experience depression more often when confronted with life stress than people without ADHD.Reference Shapero, Gibb, Archibald, Wilens, Fava and Hirshfeld-Becker 184 With mild or moderate cases of depression, treatment of ADHD should be pursued, as it can reduce the long-term risk for depressive episodes.Reference Chang, D’Onofrio, Quinn, Lichtenstein and Larsson 185 A large study in Taiwan found lower rates of antidepressant resistance when individuals with ADHD and depression received combined treatment with antidepressants and psychostimulants vs treatment with antidepressant alone.Reference Chen, Pan and Hsu 186 However, treatment of depression should take precedent over ADHD when it is the most disabling condition such as in major depressive disorder or suicidal cases. 7

Administration of both a stimulant and serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression is well-tolerated.Reference Findling 187 Atomoxetine monotherapy was also effective and well-tolerated in an open-label study of adolescents with ADHD and major depressive disorder; although, it was only effective for ADHD symptoms.Reference Atomoxetine, MDDSG and Bangs 188 Caution must be taken when prescribing amphetamine with certain medications, as there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when combined with buspirone, fentanyl, lithium, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, St. John’s Wort, triptans, tricyclic antidepressants, tramadol, and tryptophan. 22

Insomnia

Insomnia is common in individuals with ADHD before ever receiving treatment and can be either worsened or improved with ADHD medication. One study found >80% of unmedicated children with ADHD had at least one sleep problem including involuntary movement, difficulty falling asleep or rising, sleepwalking, snoring, bed-wetting, or nightmares.Reference Corkum, Moldofsky, Hogg-Johnson, Humphries and Tannock 189 Insomnia occurs in 55% to 80% of adults with ADHD, with the combined ADHD subgroup showing higher rates of insomnia than the inattentive subgroup.Reference Brevik, Lundervold and Halmoy 190

Initial insomnia is a frequent side effect when starting an ADHD medication, although patients may experience an improvement in sleep quality with appropriate treatment over time. 191–194 In our experience, a medication with too long of a duration may exacerbate insomnia for some individuals, while, for others, a formulation with a small amount of medication released in the early evening may help to calm the brain, decrease restlessness, and improve sleep quality.Reference Weisler, Young and Mattingly 194 If insomnia is an issue with a stimulant medication, the clinician should adjust the dose or try an alternative delivery formulation. Atomoxetine is less likely to cause insomnia and other sleep issues, and can be considered as a second-choice option.Reference Hollway, Mendoza-Burcham and Andridge 195 , Reference Sangal, Owens, Allen, Sutton, Schuh and Kelsey 196 Guanfacine and clonidine induce sedation, and may be used alone or in combination with stimulants. 197–199 Prescribing a treatment such as melatonin to specifically address sleep issues may be needed in certain individuals.Reference Barrett, Tracy and Giaroli 200

Neurological conditions: autism, epilepsy, and tics

Autism spectrum disorders

ASD is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interactions in many settings and the presence of repetitive, restricted behavior, interests, or activities. 6 Diagnosis of co-occurring ADHD and ASD was recently endorsed in DSM-V. 6 ADHD and ASD co-occur at all stages of life,Reference Hartman, Geurts, Franke, Buitelaar and Rommelse 201 with around 75% of children and adolescents with ASD having comorbid ADHD.Reference Joshi, Faraone and Wozniak 202 , Reference Lee and Ousley 203 Similar to ADHD, the symptoms and presentation of ASD change with age.Reference Hartman, Geurts, Franke, Buitelaar and Rommelse 201 These patients are often extremely sensitive to side effects from ADHD medication; treatment-emergent agitation, increase in stereotypies, or worsening of anxiety can be frequent concerns.

To find the optimal dose, we recommend starting with a low dose and titrating slowly. Liquid formulations of methylphenidate (eg, Qullivant XR, 204 Methylin 68) or amphetamine (eg, Dyanavel XR, ProCentra, 30 Adzenys ER 21) can be titrated in very minor amounts and may aid slow titration. Swallowing issues are frequently encountered in this population and liquid, orally disintegrating, or sprinkled formulations may be beneficial. The British Association for Psychopharmacology recommends methylphenidate as the first-choice pharmacotherapy, atomoxetine as the second choice, and guanfacine and clonidine as third-line options.Reference Howes, Rogdaki and Findon 205 In our clinical experience, all classes of ADHD medication can prove beneficial in patients with ASD/ADHD and the response varies dramatically between each patient.

Epilepsy

Approximately one-third of children with active epilepsy have comorbid ADHD.Reference Reilly, Atkinson and Das 206 Evidence-based recommendations on treatment of ADHD in epilepsy are limited. The Task Force on Comorbidities of the International League Against Epilepsy Pediatric Commission recommends methylphenidate as the first-choice treatment because there is a 65% to 83% improvement in ADHD symptoms without significantly increasing the frequency or severity of seizures.Reference Auvin, Wirrell and Donald 207 Atomoxetine has also shown efficacy in treating ADHD in this population, but there is limited evidence regarding safety.Reference Auvin, Wirrell and Donald 207

Tic disorders

About 5% to 15% of children with ADHD also have a tic disorder.Reference Poh, Payne, Gulenc and Efron 208 , Reference Steinhausen, Novik and Baldursson 209 These patients experience poorer quality of life than those with ADHD alone.Reference Poh, Payne, Gulenc and Efron 208 , Reference Steinhausen, Novik and Baldursson 209 Overall ADHD medications can be effective in these patients when used with appropriate care and consideration.Reference Osland, Steeves and Pringsheim 210 With stimulant pharmacotherapy, monitor for possible worsening of tics. 19 Atomoxetine is unlikely to worsen tics, and can be considered if stimulants cause tic exacerbation.Reference Osland, Steeves and Pringsheim 210 Guanfacine and clonidine are often effective at treating ADHD with coexisting tic disorder and may improve comorbid tics.Reference Osland, Steeves and Pringsheim 210

Conclusions and Future Directions

Evolving ADHD symptomology and comorbid disorders contribute to the complexity of a treatment plan for patients with ADHD over their lifetimes. Despite this, it is necessary to find the most effective treatment for the individual with ADHD to be able to improve many aspects of his or her life. Notwithstanding the many treatment challenges for patients with ADHD, clinicians have numerous options for FDA-approved ADHD pharmacotherapy allowing individualized medication to meet specific patient needs. Understanding the key challenges of ADHD treatment for different age groups and for patients with various co-occurring disorders is necessary to achieve successful treatment results. Further research is needed to develop better treatment strategies for individuals diagnosed with ADHD and comorbid neurological disorders such as epilepsy, insomnia, and tic disorders. Although not discussed in this review, the association of ADHD with certain inherited neurological diseases such as Fragile X syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, Williams syndrome, and Velo-cardio-facial syndrome is becoming evident.Reference Elia, Gai and Xie 211 , Reference Sullivan, Hatton and Hammer 212 Accordingly, further research into the treatment of ADHD comorbid with these inherited disorders would be valuable.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Nicole Seneca, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC, King of Prussia, PA, and was funded by Neos Therapeutics, Inc. All authors are responsible for the scientific content of this article.

Funding

The authors did not receive funding for the preparation of this manuscript. Neos Therapeutics, Inc., provided funding to AlphaBioCom, LLC, for medical writing and editorial support for this manuscript.

Disclosures

Greg W. Mattingly serves as a Speaker for Alkermes, Allergen Ironshore, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sunovion, and Takeda; as a consultant for Akili, Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome, Ironshore, Intracellular, Ironshore, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Neos, Purdue, Rhodes, Sage, Sunovion, Takeda, and Teva; and is a researcher for Akili, Alkermes, Allergan, Axsome, Boehringer, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medgenics, NLS-1 Pharma AG, Otsuka, Reckitt Benckiser, Roche, Sage, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. Leticia Ugarte has nothing to disclose. Joshua Wilson reports potential conflicts of interest for his work with Akili, Alkermes, Allergan, Boehringer, Janssen, Medgenics, NLS-1, Pharma AG, Otsuka, Reckitt Benckiser, Roche, Sage, Sunovion, Supernus, and Takeda. Paul Glaser was on the Neos Speaker’s Bureau over 3 years ago.