Behavior reflecting self-victimization is increasingly widespread in adolescent community samples (Gallimberti et al., Reference Gallimberti, Buja, Chindamo, Lion, Terraneo, Marini and Baldo2015; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Wong, McIntyre, Wang, Zhang, Tran and Ho2019), which includes nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), that is, the deliberate injury to one's own body tissue without conscious suicidal intent (Nock, Reference Nock2010), and substance use, that is, the harmful use of psychoactive substances, such as cannabis and others (Gallimberti et al., Reference Gallimberti, Buja, Chindamo, Lion, Terraneo, Marini and Baldo2015; Ramo, Liu, & Prochaska, Reference Ramo, Liu and Prochaska2012). In addition, victimization by peers such as physical aggression (e.g., being hit or kicked), verbal aggression (e.g., being insulted or called names), and relational aggression (e.g., being excluded from the peer group) is common among adolescents (Bowes, Joinson, Wolke, & Lewis, Reference Bowes, Joinson, Wolke and Lewis2015; Jenkins, Fredrick, & Wenger, Reference Jenkins, Fredrick and Wenger2018). NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization have been linked to severe psychological problems, including suicide (Bilen et al., Reference Bilen, Ottosson, Castren, Ponzer, Ursing, Ranta and Pettersson2011; Cipriano, Cella, & Cotrufo, Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2017; Jacobson & Gould, Reference Jacobson and Gould2007; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; Nitkowski & Petermann, Reference Nitkowski and Petermann2011). It is, therefore, pivotal to identify factors that may promote or maintain self- and peer victimization in order to develop effective prevention or intervention measures.

Increasing evidence showed that NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization are all associated with broad personality dimensions, particularly high neuroticism (Hansen, Steenberg, Palic, & Elklit, Reference Hansen, Steenberg, Palic and Elklit2012; Jacobson & Gould, Reference Jacobson and Gould2007; Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, Reference Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt and Watson2010; Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker, & Kelley, Reference Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker and Kelley2007). These findings suggest that self- and peer victimization may also be associated with other personality traits, particularly the ones which have relations with neuroticism, internalizing problem behavior, and/or peer victimization. Justice sensitivity (JS), that is, the tendency to perceive injustice and adversely respond to it (Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes, & Arbach, Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005), is such a personality trait (Bondü & Inerle, Reference Bondü and Inerle2020; Bondü, Rothmund, & Gollwitzer, Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005). However, it is unknown if there is a link between JS and self-victimization (i.e., NSSI and substance use). In addition, only one study to date examined the association between JS and victimization by peers (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016).

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury, Substance Use, and Victimization by Peers

NSSI comprises a broad range of deliberate behavior that causes injury and often pain to oneself, such as cutting oneself with various objects, preventing wounds from healing, or swallowing improper subjects (Zetterqvist, Reference Zetterqvist2015). Individuals engaging in NSSI often perceive an irresistible, repeated impulse to self-harm, increasing tension before acting on this impulse, and feelings of relief thereafter (Hawton, Saunders, & O'Connor, Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012; Zetterqvist, Reference Zetterqvist2015). The lifetime prevalence rate of NSSI is high, that is, 18% in community samples and over 40% in clinical samples (Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018; Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, Reference Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl2005; Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape, & Plener, Reference Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape and Plener2012; Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St John, Reference Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking and St John2014). This is alarming because NSSI shows high comorbidity with other personality and affective disorders, and particularly with borderline personality disorder (Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018). Furthermore, individuals engaging in NSSI are more likely to commit suicide than those who do not engage in NSSI (Hawton, Zahl, & Weatherall, Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall2003).

In addition to NSSI, the use of substances (i.e., cannabis, stimulants, hallucinogens, or opioids) is also increasingly common among young individuals (Compton, Thomas, Stinson, & Grant, Reference Compton, Thomas, Stinson and Grant2007; UNODC, 2015) with prevalence rates ranging from 12% to 18% in adolescence (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Thomas, Stinson and Grant2007; Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016). The repeated persistent use of the substances may result in adverse consequences, such as loss of control over the and hazardous use, substance tolerance, and impairments in physical health, social relationships, or performance (APA, 2013). In addition, substance use shows high comorbidity rates with other mental disorders, such as affective, personality, or psychotic disorders (Compton et al., Reference Compton, Thomas, Stinson and Grant2007). Hence, NSSI and substance use are similar in providing short-term stress release, but potentially causing adverse consequences to the individuals in the long run.

Finally, victimization is often inflicted not by the individuals themselves but by others, such as peers. The estimated prevalence of victimization by peers is high with a range from 10% up to 35% among children and adolescents (Due, Holstein, & Soc, Reference Due, Holstein and Soc2008; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Verlinden, Berkel, Mieloo, van der Ende, Veenstra and Tiemeier2012). Particularly, repeated victimization by peers has critical long-term consequences, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms and impairments in other areas of life (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, Reference Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel and Loeber2011, for a meta analysis; Wolke, Copeland, Angold, & Costello, Reference Wolke, Copeland, Angold and Costello2013).

Adolescence is a critical phase for the development and maintenance of both self- and peer victimization. NSSI and substance use are likely to emerge during adolescence (Cipriano et al., Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2017; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Collin, Munafò, MacLeod, Hickman and Heron2017), and peer victimization is common in adolescence (Arseneault, Reference Arseneault2018). During adolescence, increasing educational and social demands as well as increasing importance of peers may promote more social anxiety and fear of rejection (Waylen & Wolke, Reference Waylen and Wolke2004). Girls are more likely to engage in NSSI than boys (Bresin & Schoenleber, Reference Bresin and Schoenleber2015; Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018; Nock, Reference Nock2010), whereas boys are more likely to use substances (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016) and to experience peer victimization than girls (Smith, López-Castro, Robinson, & Görzig, Reference Smith, López-Castro, Robinson and Görzig2019).

Apart from the importance of age and sex, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization share further risk factors. One common underlying problem is the habitual tendency to experience negative emotions as captured by the trait neuroticism. In addition, impaired emotion regulation skills, that is, difficulties in adequately modulating and coping with these negative emotions were suggested to create a vulnerability for NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization (Bierman, Kalvin, & Heinrichs, Reference Bierman, Kalvin and Heinrichs2015; Jacobson & Gould, Reference Jacobson and Gould2007; Junker, Nordahl, Bjorngaard, & Bjerkeset, Reference Junker, Nordahl, Bjorngaard and Bjerkeset2019; Lloyd-Richardson et al., Reference Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker and Kelley2007). NSSI and substance use may be dysfunctional coping mechanisms in the face of such negative events (Gratz & Chapman, Reference Gratz and Chapman2007; Kober, Reference Kober and Gross2014), whereas negative behavior associated with emotion dysregulation may predispose to rejection and victimization by peers. Taken together, these findings suggest that personality traits which also predispose individuals to experience negative emotions and strain, such as JS, may also promote NSSI, substance use, and or victimization by peers.

Given the similarities between NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization, it is not surprising that they have associations with each other as well. There is extensive evidence that NSSI and substance use either co-exist or that NSSI predicts later substance use (Haug, Núñez, Becker, Gmel, & Schaub, Reference Haug, Núñez, Becker, Gmel and Schaub2014; Kaminer & Bukstein, Reference Kaminer and Bukstein2008; Tharp-Taylor, Haviland, & D'Amico, Reference Tharp-Taylor, Haviland and D'Amico2009), and that peer victimization is associated with an elevated risk of both NSSI and substance use (Lereya et al., Reference Lereya, Winsper, Heron, Lewis, Gunnell, Fisher and Wolke2013; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Norman, Suetani, Thomas, Sly and Scott2017; Zapolski, Rowe, Fisher, Hensel, & Barnes-Najor, Reference Zapolski, Rowe, Fisher, Hensel and Barnes-Najor2018). Thus, it seems reasonable to simultaneously investigate potential risk factors for all of these problems.

Justice Sensitivity (JS)

JS is a personality trait that captures individual differences in the disposition to frequently perceive and negatively react to injustice (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005). Individuals high in JS are hypervigilant towards, interpret even ambiguous situations as, and tend to ruminate about injustice (Schmitt, Neumann, & Montada, Reference Schmitt, Neumann and Montada1995, Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010). Individuals’ affective responses to injustice depend on the perspective from which it is perceived: Victim JS indicates the tendency to feel unfairly treated or being taken advantage of and is primarily associated with anger; observer JS indicates the tendency to perceiving others being unfairly treated and is primarily associated with indignation; perpetrator JS indicates the tendency to feeling unfairly treating others and is primarily associated with guilt (Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer, & Maes, Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010).

The individual differences in JS can be validly and reliably measured from middle childhood onwards and from adolescence onwards and the stability rates of the different JS perspectives are similar to those of adults (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005). Girls tended to report higher mean levels of JS, particularly observer and perpetrator JS, but the factor structure was shown to be equal for boys and girls (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015).

All JS perspectives are positively correlated, but only victim JS reflects self-oriented concerns for justice (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010). High victim JS was positively associated with other rather negatively evaluated traits, such as Machiavellism, paranoia, vengeance, jealousy, and suspiciousness (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010). In contrast, observer and perpetrator JS reflect altruistic concerns for injustice and are positively associated with good social skills, such as empathy, role taking, and social responsibility (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005). The differences between the JS perspectives are reflected in differential associations with prosocial and antisocial behaviors as well as internalizing problems. Previous findings suggest that JS may also show relations with measures of victimization by self and others (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016).

Potential Links between Justice Sensitivity, Nonsuicidal Self-Injury, Substance Use, and Victimization by Peers

There are several reasons to expect associations between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization. First, all JS perspectives were positively related to neuroticism (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005) and a broad range of adverse emotions, including sadness, disappointment, guilt, anger, or helplessness (Bondü & Inerle, Reference Bondü and Inerle2020), which are also common among individuals who engage in NSSI, use substances, and are victimized by peers. Thus, high JS might be an indicator of the inability to regulate one's emotions which might make justice-sensitive individuals more vulnerable to engage in NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization (Schwartz, Proctor, & Chien, Reference Schwartz, Proctor, Chien, Juvonen and Graham2001).

Second, in addition to the similarities in affective aspects, JS captures the cognitive tendency to experience strain in the face of and to ruminate about alleged injustice (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005). Thus, high JS, particularly high victim JS, may promote the generation of stress and a negatively biased interpretation of the situation (Liu, Kraines, Massing-Schaffer, & Alloy, Reference Liu, Kraines, Massing-Schaffer and Alloy2014; Normansell & Wisco, Reference Normansell and Wisco2017), which may be associated with using avoidant problem solving strategies to deal with them (Kraines & Wells, Reference Kraines and Wells2017). NSSI and substance use may be two of these avoidant strategies individuals use to cope with perceptions of injustice and the strain associated with these perceptions, which is potentially associated with further problems in social interactions, and subsequent adverse mental states (Downey, Mougios, Ayduk, London, & Shoda, Reference Downey, Mougios, Ayduk, London and Shoda2004; Gao, Assink, Cipriani, & Lin, Reference Gao, Assink, Cipriani and Lin2017). Victimization by peers may be considered as unjust and, therefore, may add to the perceptions of strain. It has also been shown to be related to rumination (Barchia & Bussey, Reference Barchia and Bussey2010). Finally, NSSI and substance use are characterized by perseverating thoughts of the act or the substance before acting on the urge of engaging in these behaviors (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Nock, Reference Nock2010). Hence, victim JS comprises both affective and cognitive aspects and processes that are similar to or may predispose to (self-)victimization.

Third, increasing evidence indicates that smaller personality traits, which capture vulnerabilities towards specific negative social cues, such as injustice, may contribute to the development and maintenance of mental health problems (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak, & Esser, Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017; Fontana et al., Reference Fontana, De Panfilis, Casini, Preti, Richetin and Ammaniti2018; Gardner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Gardner and Zimmer-Gembeck2018), suggesting that JS could contribute to the development of NSSI, substance use, and victimization by peers as well. Particularly, victim JS has been positively associated with externalizing problems, such as aggression, conduct problems, bullying, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Bondü & Esser, Reference Bondü and Esser2015; Bondü & Krahe, Reference Bondü and Krahe2015; Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016), as well as with internalizing problems, including emotional problems, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Bondü & Inerle, Reference Bondü and Inerle2020; Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017). Observer JS showed mostly negative associations with externalizing problems, but positive associations with internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms and eating behavior pathology (Bondü, Bilgin, & Warschburger, Reference Bondü, Bilgin and Warschburger2020). Perpetrator JS showed negative associations with externalizing (Bondü & Krahe, Reference Bondü and Krahe2015; Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016; Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017) and positive or nonsignificant associations with internalizing problems. These associations suggest that JS might also predict other adverse behaviors related to internalizing and externalizing problems, such as NSSI, substance use, and problems with peers.

Fourth, specifically peer relationships play an important role in engaging in NSSI and using substances during adolescence (Adler & Adler, Reference Adler and Adler2011). Hence, theories building on the link between social relationships and deviance, such as General Strain Theory (GST) (Agnew, Reference Agnew1992; Reference Agnew2006), provide further background for the explanation of the association between JS and NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization in young individuals. GST emphasizes that stressful social interactions, such as rejection and victimization by peers and negative experiences at school pressure individuals to engage in deviant acts (i.e., criminal behavior, use of illegal drugs, and self/other directed aggressive behavior) due to the violation of the basic norms of justice (Agnew, Reference Agnew1992). Strain perceived as unjust rather than merely unfortunate was assumed to have the strongest associations with deviant behaviors due to resulting in the most negative emotional states (Agnew, Reference Agnew2001). Particularly anger was emphasized as the most critical emotional reaction for producing deviance (Agnew, Reference Agnew1992). Given that anger is considered as a particularly strong emotion both in victim JS and in NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization (Bondü & Richter, Reference Bondü and Richter2016b; Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, DeFife, Guarnaccia, Phifer, Fani, Ressler and Westen2011; Kochenderfer-Ladd, Reference Kochenderfer-Ladd2004; Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, Reference Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl2005; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Neumann and Montada1995), associations between these maladaptive behaviors and victim JS should be particularly pronounced.

Fifth, JS may be particularly influential during adolescence not only due to the increasing importance of peer relationships (Waylen & Wolke, Reference Waylen and Wolke2004), but also because justice norms are especially important and inflexible during this developmental period (Birkeland, Melkevik, Holsen, & Wold, Reference Birkeland, Melkevik, Holsen and Wold2012), which may include several unjust experiences, such as in peer interactions, school performance, or emerging partner relationships (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015). Hence, individuals high in JS may be particularly vulnerable towards unjust experiences, and, consequently maladaptive behavior during this period.

Finally, accumulating evidence shows that JS also is an outcome of mental health problems. For example, depressive symptoms predicted higher subsequent victim JS (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017), eating disorder pathology predicted higher subsequent victim and observer JS (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Bilgin and Warschburger2020) in adolescents. One previous study showed no bidirectional links between victimization by peers and JS in the total group, but victimization predicted an increase in victim JS in girls, but a decrease in victim JS in boys over a one-year period (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016), suggesting a sensitization towards unfair treatment in girls, but a desensitization in boys. Taken together, these findings suggest that NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization may also influence JS, but the previous finding concerning peer victimization requires replication in other samples and with longer durations.

The Current Study

To the best of our knowledge this is the first study to investigate the prospective links between JS and measures of self-victimization, such as NSSI and substance use. Only one previous study examined the links between JS and peer victimization. The current study undertakes a cross-lagged approach with three points of measurement to examine potential bidirectional associations. That way, the present study adds to the existing research by relating JS to further mental health problems, by examining potential risk factors for (self-) victimization with longitudinal data, and by considering potential moderating effects of sex which is important due to pertinent sex differences in both JS and the outcome measures. To illustrate, girls are more likely to engage in NSSI and report higher victim, observer, and perpetrator JS; whereas boys are more likely to use substances, be victimized by peers, and have lower JS scores in all perspectives (Bondü & Inerle, Reference Bondü and Inerle2020; Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, López-Castro, Robinson and Görzig2019). These findings may suggest differential relations between the study variables in boys and girls. In line with the theoretical assumptions and previous research outlined above, we expected that (a) individuals who engaged in NSSI, used substances, and were victimized by peers will report higher levels of victim and observer JS and lower levels of perpetrator JS than individuals who did not at each assessment points, (b) bidirectional association between JS and NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization with victim JS and observer JS showing positive and perpetrator JS showing negative longitudinal links, and (c) sex to moderate the longitudinal associations between the study variables: associations regarding NSSI will be more pronounced for girls and associations for substance use and peer victimization will be more pronounced for boys.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from a previous study on developmental risk factors. For the present study, participants were assessed between 2011 and 2012 at ages 9–19 (T1), between 2013 and 2014 at ages 11–21 (T2), and between 2015 and 2016 at ages 14–22 years (T3). Of the initial sample, 1,665 children participated in T1 and/or T2. In the present study, we included all 769 participants who took part in the study from T1 to T3 (46.2% retention rate). In the final sample, the mean age of the participants was 16.77 years (SD = 2.01) at T3; 55.7% were females, and 45.9% had parents with university entrance qualification. Concerning study attrition, more males (N = 498) than females (N = 398) dropped out of the study (χ 2 = 20.9, p < .001). Participants who dropped out (M = 13.73, SD = 1.97) were significantly older at T1 than participants who remained in the study (M = 13.04, SD = 1.99), t(1,502) = 6.72, p < .001. Furthermore, participants who dropped out had lower observer and perpetrator JS at T1 (M = 2.78, SD = 1.20 and M = 3.16, SD = 1.32) than participants who remained in the study (M = 3.04, SD = 1.11 and M = 3.56, SD = 1.18), t(1,484) = −4.25, p < .001 and t(1,484) = −6.256, p < .001.

Measures

Justice Sensitivity (JS). We measured JS using the five-item short version of the Justice Sensitivity Inventory for Children and Adolescents (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010) at all three measurement points. The scale captures emotional and cognitive reactions to the perception of injustice from three perspectives: Victim (“It makes me angry when I am treated worse than others”), observer (“I am upset when someone is…”), and perpetrator (“I feel guilty when I treat someone…”). Response options range from 0 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The scale was shown to be valid and reliable (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Baumert, Gollwitzer and Maes2010). We computed mean scores separately for the three subscales.

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI). Participants who indicated to engage in NSSI in a filter item were asked to report on six common methods of self-harm using the following yes/no items translated and adapted from Klonsky and Glenn (Reference Klonsky and Glenn2009) and Gratz (Reference Gratz2001) at T2 and T3: (a) burning and/or cutting, (b) stabbing the skin using needles and/or staples, (c) preventing wounds from healing, (d) beating themselves or hitting their head against objects, (e) swallowing dangerous substances and/or objects, and (f) hurting themselves in a different way. We calculated two test halves scores from these six items, which were used to create latent variables at T2 and T3, which were set to zero for participants who did not report any self-injuring behavior. In order to investigate group comparisons, we created a dichotomous variable at both T2 and T3 with 0 = participants who never engaged in NSSI; 1 = participants who engaged in NSSI.

Substance Use. Participants reported on their use of illegal substances during the last 6 months at T2 and T3 using two questions: (a) How many times have you consumed cannabis (e.g., smoked, in cookies)?; (b) How many times have you consumed other illegal drugs (e.g., ecstasy, speed, cocaine, crystal meth). Response options were 0 = never, 1 = less than once a month, 2 = once a month, 3 = once a week, 4 = every day. We used these continuous scores in the latent analyses. We created a dichotomous score for group comparisons (0 = nonuser; 1 = substance use).

Peer Victimization. Participants reported on peer victimization at T2 and T3 using a five-item questionnaire covering physical, verbal, and relational forms of aggression (e.g., “Other students have insulted me”) (Espelage, Bosworth, & Simon, Reference Espelage, Bosworth and Simon2000). Response options ranged from 1 = never to 6 = very often. We computed T2 and T3 peer victimization mean scores and used them in the latent analyses. For the T2 and T3 group comparisons, we used a dichotomous variable (0 = no or low peer victimization; 1 = high peer victimization), where high peer victimization was defined based on a score +1.5 SD higher from the mean score of the total sample at the respective measurement point.

Analysis

We firstly examined (a) sex differences in the justice-sensitivity subscales, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization controlling for participant age at T1 and (b) differences in the JS subscales between participants who did and did not engage in NSSI, use substances, and experienced victimization by peers at each assessment point via separate multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVAs) controlling for sex and age, respectively.

We secondly conducted a longitudinal latent cross-lagged path analysis using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2015) in order to investigate the longitudinal, bidirectional associations between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization including covariance terms, stability paths, and cross-lag paths. JS subscales, peer victimization, and NSSI were indicated by test-halves, respectively, substance use was indicated by the two items. Corresponding test halves of the three JS subscales were allowed to correlate within each assessment point due to the similarities in item wordings between the subscales (i.e., the first T1 victim JS test-half score was allowed to correlate with the first T1 test-half scores of observer and perpetrator JS; and the first T1 test-halves of observer and perpetrator JS were allowed to correlate. We applied the same pattern to the second test halves and for correlations of test-halves within T2 and T3) and with the same test-halves at the other assessment points. (The first T1 test-half of victim JS were allowed to correlate with the first T2 and T3 test-halves of victim JS; and T2 and T3 test-halves of victim JS were allowed to correlate. We applied the same pattern to observer and perpetrator JS).

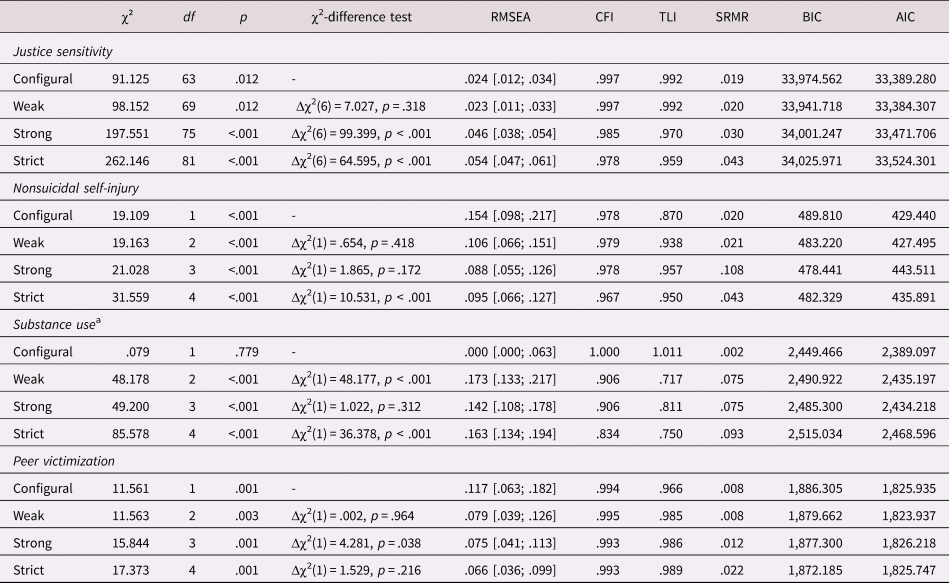

In order to ensure that our measures had the same meaning across points of measurement, we tested configural (parameters freely estimated), weak (factor loadings constrained equal), strong (factor loadings and intercepts constrained equal), and strict (factor loading, intercepts, and residual variances constrained equal) measurement invariance (MI) for all variables (Table 1). To assess the model fit, we inspected values of and changes in absolute fit indices. Comparative fit index (CFI)/ Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.06, and/or CFI decreases < .01 indicated good or negligible decreases in model fit (Cheung & Rensvold, Reference Cheung and Rensvold2002). Strong MI showed the best fit for JS, peer victimization and NSSI. Regarding substance use, the model for configural MI showed the best fit, but yielded a warning message, whereas the second-best fitting model for strong MI converged without problems. Thus, we assumed strong MI for all variables.

Table 1. Measurement invariance for justice sensitivity, nonsuicidal self-injury, substance use, and victimization by peers

Notes. χ2 = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis Index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; Bayesian information criteria; AIC = Akaike information criteria

a Please note that the configural model yielded an error message about a negative variance between substance use variables at T2 and T3, we thus assumed strong measurement invariance for substance use which shows the second-best model fit.

Afterwards, we analyzed the longitudinal associations between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization using cross-lagged panel model. All predictors were allowed to correlate at T1 and T2. At T3, correlations of error terms between the three JS subscales were allowed and estimated as were the correlations of error terms between NSSI and substance use. All other T3 correlations of error terms were restricted to zero. Parents’ highest educational achievement was used as a control variable. To assess the model fit, we inspected χ2 test as well as values of and changes in absolute fit indices. Nonsignificant chi square values, CFI/TLI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.05, SRMR < 0.06 (Browne & Cudeck, Reference Browne and Cudeck1992; Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Reference Hooper, Coughlan and Mullen2008; Hu, Bentler, & Kano, Reference Hu, Bentler and Kano1992) indicated good model fit. We used a maximum likelihood estimator and missing data were replaced using the full information maximum likelihood procedure. p values were calculated for each path coefficient. p < .05 was considered to be significant. After running the model for the total group, we examined the potential moderating role of sex in two multigroup models. In the first model, path coefficients were constrained to be equal for boys and girls. In the second model, path coefficients were allowed to vary in magnitude between the two groups. We then used χ²-differences to test whether the constrained or the unconstrained model showed a better fit with the data and interpreted the model with the better fit. We assumed strong measurement invariance between boys and girls, but in order for the model to converge without error messages, only assumed weak measurement invariance of JS and NSSI over time in these models.

Results

Descriptives

Of the participants, N = 35 (4.9%) engaged in any kind of NSSI behavior at T2, whereas N = 69 (9.1%) engaged in NSSI at T3. Burning and/or cutting was the most common method at both assessment points, N = 33 (4.6%) and N = 61 (8.0%), respectively. At T2, N = 74 (10.3%) participants reported substance use: N = 73 (10.1%) participants reported cannabis use and N = 7 (1.0%) reported illegal drug use. The percentage of substance use increased at T3 (N = 159, 20.9%), where the percentage of cannabis use increased two-fold (N = 157, 20.7%) and illegal drug use increased four-fold (N = 31, 4.1%). Similar numbers of participants were victimized by their peers at T2 (N = 67, 9.3%) and at T3 (N = 64, 8.4%).

Regarding sex differences, girls reported higher victim JS than boys at T2 and T3, higher observer JS at all measurement points, higher perpetrator JS at T1 and T3, more NSSI at T2 and T3, less peer victimization at T2 and T3, and less substance use at T3 (Table 2).

Table 2. Internal consistencies, mean values, and standard deviations of all measures for the total sample and separately for boys and girls

T1: Time 1; T2: Time 2; T3: Time 3; JS: justice sensitivity; NSSI: nonsuicidal self-injury

Significant sex differences: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Please note that the analyses were controlled for T1 age

Participants who engaged in NSSI reported significantly higher victim JS at both T2 and T3 and significantly lower levels of perpetrator JS at T2 than participants who did not (Table 3). Participants who used substances reported higher victim JS at T3 and lower levels of perpetrator JS at T2 and T3 than participants who did not. Participants who were often victimized by their peers reported higher victim and observer JS than participants who were seldom victimized by their peers at T2. There were no significant differences at T3.

Table 3. Mean values, and standard deviations by nonsuicidal self-injury, substance use and peer victimization

Note: T2: Time 2; T3: Time 3; JS: justice sensitivity; NSSI: nonsuicidal self-injury

Significant differences: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Please note that the analyses were controlled for sex and T1 age

JS perspectives, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization were moderately stable (Table 4). NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization were unrelated except for a correlation between T3 victimization and NSSI. Victim JS showed small positive relations with all outcome variables at least once. Perpetrator JS showed small negative relations with victimization and NSSI at least once. Only T3 observer JS showed a negative correlation with T3 victimization and a positive correlation with T2 substance use.

Table 4. Correlations between study variables

Note: T1: Time 1; T2: Time 2; T3: Time 3; JS: justice sensitivity; NSSI: nonsuicidal self-injury; *p < .05; **p < .01

Cross-Lagged Associations between JS, NSSI, Substance Use, and Peer Victimization

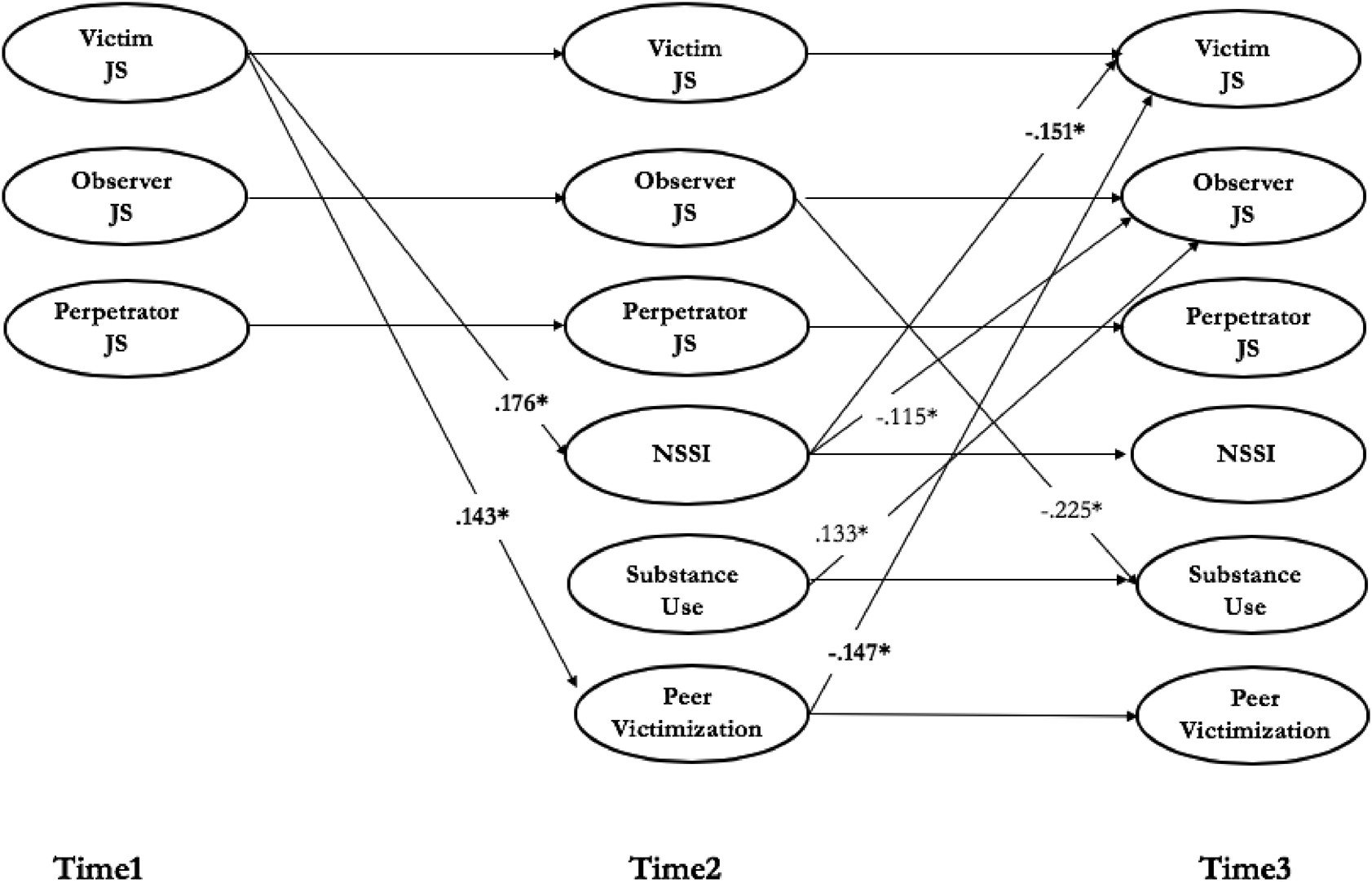

The model fit of the overall model including the full sample was good: χ2(321) = 564.301, p < .001; CFI = .979; RMSEA = .031[.027;.036]; SRMR = .037. Figure 1 shows statistically significant paths. For the ease of interpretation, nonsignificant path coefficients and correlations were omitted from the figure but retained in the model (all estimates for path coefficients in Supplementary Table S1). The JS latent factors showed moderate to high stabilities from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3. There was a high stability between T2 and T3 substance use (β = .519, p < .001), and a moderate stability between T2 and T3 peer victimization (β = .329, p < .001) and NSSI (β = .360, p < .001). Higher T1 victim JS predicted more T2 NSSI (β = .121, p = .049), substance use (β = .135, p = .025), and victimization by peers (β = .139, p = .009). Higher T2 victim JS predicted more T3 substance use (β = .108, p = .041). T1 perpetrator JS predicted lower T2 substance use (β = −.134, p = .035). Higher T2 observer predicted lower T3 substance use (β = −.147, p = .023), whereas T2 substance use predicted higher T3 observer JS (β = .121, p = .007). Finally, T2 peer victimization predicted lower T3 perpetrator JS (β = −.086, p = .018).

Figure 1. Cross-lagged model of associations between justice sensitivity (JS), nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), substance use, and victimization by peers, including the variances and covariances, stability, and cross-lags in the total sample. Model fit: χ2(321) = 564.301, p < .001; comparative fit index (CFI) = .979; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .031 [.027; .036]; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .037; N = 769. Please note that covariance coefficients are not shown in the figure to allow ease of interpretation, but retained in the model.

Concerning the potential moderating role of sex, the model with path coefficients allowed to vary between groups (χ2(651) = 990.783, p < .001; CFI = .971; RMSEA = .037 [.032;.041]; SRMR = .065) fit the data better than the model with path coefficients constrained to be equal between girls and boys (χ2(717) = 1,328.449, p < .001; CFI = .948; RMSEA = .047 [.043;.051]; SRMR = .109; Δχ2 = 337.666, Δdf = 66, Δp < .001). This finding indicates substantial differences between the longitudinal relations of the study variables between boys and girls. Hence, we interpreted the model with sex-specific findings: Partly in line with Hypothesis 3, in girls, T1 victim JS predicted higher T2 NSSI and peer victimization (Figure 2). T2 peer victimization predicted lower T3 victim JS. In boys, T2 observer JS predicted less T3 substance use. There were two marginally significant effects of T1 and T2 victim JS on higher T2 and T3 substance use, respectively. T2 NSSI predicted lower, T2 substance use predicted higher observer JS. There was an only marginally significant effect of T2 victimization on lower T3 perpetrator JS.

Figure 2. Cross-lagged model of associations between justice sensitivity (JS), nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), substance use, and victimization by peers, including the variances and covariances, stability, and cross-lags by sex (male/female). Scores for the female group are indicated by bold type. Model fit: χ2(651) = 990.783, p < .001; comparative fit index (CFI) = .971; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .037 [.032;.041]; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .065. Please note that covariance and stability coefficients are not shown in the figure to allow ease of interpretation, but retained in the model.

Discussion

Findings of the current study revealed that in line with the hypotheses, participants who engaged in NSSI, used substances, and were victimized by their peers tended to have higher victim JS and lower perpetrator JS. Furthermore, those who were victimized by their peers tended to have higher observer JS cross-sectionally. Thus, these behaviors and experiences were associated with more negative affective and cognitive responses towards perceived unfair treatment and less expressed negative responses towards inflicting injustice onto others. Regarding longitudinal associations, victim JS at T1 was associated with higher T2 NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization when the stability of these variables was not considered. Victim JS at T2, however, was still associated with higher T3 substance use when its stability was controlled for. That is, being sensitive to one's own unjust treatment may predispose individuals to be victimized both by others and themselves. In contrast, there were negative bidirectional associations between substance use and observer and/or perpetrator JS between T2 and T3. This indicates that the tendency to care for justice for the sake of others may protect individuals from substance use and that substance use may be associated with a concern for other's just treatment. These findings were further qualified by sex differences. In girls, T1 victim JS was associated with higher T2 NSSI and peer victimization, T2 NSSI was associated with lower T3 victim JS. In boys, there was a negative bidirectional association between observer JS and substance use: T2 substance use was associated with higher T3 observer JS, observer JS at T2 was associated with lower T3 substance use. Furthermore, T2 NSSI was associated with lower T3 observer JS. Taken together, JS and (self-)victimization showed small but significant concurrent and prospective bidirectional associations.

General Findings

The prevalence rates of NSSI, substance use, and victimization were similar to those reported in previous research (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Nock, Reference Nock2010). Also in line with previous research, girls were more likely to engage in NSSI, less likely to use substances, and less likely to be exposed to peer victimization than boys (Bresin & Schoenleber, Reference Bresin and Schoenleber2015; Gillies et al., Reference Gillies, Christou, Dixon, Featherston, Rapti, Garcia-Anguita and Christou2018; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Kerridge, Saha, Huang, Pickering, Smith and Grant2016; Nock, Reference Nock2010; Smith et al., Reference Smith, López-Castro, Robinson and Görzig2019). Finally, as in previous research, there was an increase in the rate of both engaging in NSSI and using substances (Cipriano et al., Reference Cipriano, Cella and Cotrufo2017; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Saha, Ruan, Goldstein, Chou, Jung and Hasin2016; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Collin, Munafò, MacLeod, Hickman and Heron2017) between T2 and T3 when the majority of the participants in the present sample made the transition into late adolescence. This indicates the reliability of our findings. Note, however, that contrasting previous findings, there were hardly any associations between the three indicators of (self-)victimization in our study.

Associations between JS, NSSI, and Substance Use

Regarding associations with indicators of self-victimization, victim JS revealed the only significant association with NSSI. This finding is in line with the reasoning that the adverse emotions as well as strain and rumination associated with perceived unjust treatment may predispose to NSSI as a strategy to cope with negative emotions and to relief strain and negative thoughts, which is a maladaptive coping and emotion regulation mechanism (Klonsky, Victor, & Saffer, Reference Klonsky, Victor and Saffer2014). This reasoning may also explain the finding that the association between victim JS and NSSI was particularly evident in girls, because previous research showed that girls use rumination more often to cope with their emotions (Selby & Joiner, Reference Selby and Joiner2009) and are more likely to report emotional reasons (e.g., “to avoid painful memories”) than boys who are more likely to report social reasons to engage in NSSI (e.g., “to show others how tough I am”) (Laye-Gindhu & Schonert-Reichl, Reference Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl2005). Thus, girls may be more likely to use NSSI as a coping strategy in the case of unfair treatment. Given that adolescents may lack the skills to cope with negative emotions related to injustice (Birkeland et al., Reference Birkeland, Melkevik, Holsen and Wold2012), specifically high victim JS may promote these problems. In addition, it was suggested that JS, particularly high victim JS, may be related with further strain due to interpreting more social interactions as unjust, expecting more negative social interactions, or attributing adverse social situations to malevolent intent similar to dysfunctional thoughts (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017). Associations between victim JS and NSSI, however, did not hold stable when the stability of NSSI was considered, indicating that adversely responding to unfair treatment does not further add to the behavior once it was established.

Regarding substance use, relations with JS were more complex. Victim JS predicted subsequent higher substance use consistently both when not considering (T1 to T2) and when considering (T2 to T3) the stability of substance use, indicating that victim JS may predispose to substance use for the same reasons that have been outlined with regard to NSSI. However, the altruistic facets of JS, namely perpetrator JS at T1 and observer JS at T2 predicted less subsequent substance use at T2 and T3, respectively, suggesting that caring for the just treatment of others may be negatively associated with using illegal substances and may level out the potential promoting effects of victim JS. This is interesting because previous research consistently showed positive relations between observer JS and internalizing problems as well as no or also positive relations between perpetrator JS and internalizing problems (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Bilgin and Warschburger2020; Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015; Bondü & Inerle, Reference Bondü and Inerle2020; Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017), whereas both were negatively related to measures of externalizing problems (Bondü & Krahe, Reference Bondü and Krahe2015). Although substance use is often considered as an example of internalizing problem behavior in psychological contexts, its relationship with JS resembles that of externalizing problem behavior. This may indicate that the characteristics of illegal substance use that bring it close to externalizing behavior, such as showing harmful/aggressive behavior towards oneself, surpassing social norms, showing illegal behavior by buying drugs, or low impulse control, are more relevant for understanding its relations with observer JS than its internalizing aspects (Martel et al., Reference Martel, Pierce, Nigg, Jester, Adams, Puttler and Zucker2009). In line with this reasoning, strong relations between antisocial behavior and substance use were documented (Obando, Trujillo, & Trujillo, Reference Obando, Trujillo and Trujillo2014).

Further findings of the current study suggested bidirectional associations between being highly sensitive to the unfair treatment of others (observer JS) and substance use, particularly in boys. Whereas T2 observer JS that was associated with empathy and prosocial behavior in previous research (Fetchenhauer & Huang, Reference Fetchenhauer and Huang2004; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes and Arbach2005) predicted lower T3 substance use, T2 substance use predicted higher T3 observer JS in the total sample and in boys. This finding is similar to the positive prospective association between eating disorder pathology and subsequent high observer JS (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Bilgin and Warschburger2020), indicating that mental health problems may not only increase the vulnerability towards own unfair treatment, but also to the unfair treatment of others. More research, however, is needed to fully understand this association, that in boys seemed to be levelled out by negative associations between T2 self-harm and T3 observer JS.

Associations between JS and Peer Victimization

It was repeatedly suggested that negative emotions, cognitions, and interactions associated with (victim) JS, may predispose individuals to problems with peers (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015). Nevertheless, the concurrent and prospective associations between JS and victimization in the present study were small. Particularly at the third assessment point, participants who experienced victimization by peers did not differ from those without similar experiences regarding victim JS. This is in line with previous research showing no cross-sectional associations between problems with peers and victim JS (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015) and no longitudinally associations between victim JS and victimization by peers (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016). Regarding the longitudinal associations in the present sample, victim JS predicted more victimization by peers in the total sample and in girls, but only when the stability of victimization was not controlled for. This gives support to the idea that having high victim JS traits could signal an inability to manage one's emotions, frequent outbursts of anger, and detrimental behavior, such as revenge, which may predispose those individuals to victimization by peers. Those children may be the ones who easily over-react to injustice and are unable to respond to peer provocation strategically (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Sahyazici-Knaak and Esser2017; D'Esposito, Blake, & Riccio, Reference D'Esposito, Blake and Riccio2011). That is, victim JS might impair peer relationships, but the effects could be small.

Concerning the longitudinal effects of victimization by peers on the perspectives of JS, previous research showed that it predicted higher victim JS in girls and lower victim JS in boys. It was assumed that these differences emerge, because social relationships tend to be more important for girls, making adverse social situations more discomforting and threatening, whereas boys may try to hide negative emotions after maltreatment by others (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016). In the present sample, however, victimization by peers predicted lower subsequent perpetrator JS in the total sample and in boys, suggesting that being victimized might be negatively associated with the concern for justice for others. It is reasonable that being exposed to peer victimization might impair an individual's ability to have concerns for treating others unfairly because being exposed to peer victimization is associated with a decrease in empathy (Malti, Perren, & Buchmann, Reference Malti, Perren and Buchmann2010). In girls, initially high victim JS was associated with higher subsequent peer victimization, which in turn was associated with lower levels of subsequent victim JS. This finding is in contrast with the finding of the previous study showing a unidirectional association, where peer victimization was associated with an increase in victim JS in girls (Bondü et al., Reference Bondü, Rothmund and Gollwitzer2016). More research is needed to explain this finding and the differences in findings between samples. One explanation emerging from the present study could be that girls experienced less peer victimization than boys and, therefore, may have less adverse experiences to cope with which may make the desensitization easier. Alternatively, girls may also not want to admit that they were hurt by victimization by peers.

In summary, only some of the hypothesized associations between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization were significant, particularly with regard to observer and perpetrator JS and when the stability of the outcome measures was considered. This could mean that the continuity of NSSI and peer victimization mainly depend on the previous instances of these variables rather than on JS. Victim JS showed the most consistent links with the outcome measures, suggesting the closest links with indicators of developmental psychopathology in line with previous research (Bondü & Elsner, Reference Bondü and Elsner2015). Furthermore, some of the significant associations depended on the sex of the participants. This may highlight the importance of sex while investigating the links between trait variables and NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization. Finally, there were fewer significant associations in the single-sex groups than the total sample. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution because sample sizes are smaller and, therefore, significant effects are harder to find in a multigroup analysis.

Limitations and Outlook

The strengths of the current study include being the first study to examine the longitudinal associations between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization using a large sample. Thus, the current study contributes to the theoretical advancement of the role of personality traits in engaging in maladaptive behavior and being exposed to aggression by others. Given the complex association between NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization, including all three of them in the same model allowed us to consider the effects of these variables on each other. Limitations included using self-report data only and not including other personality traits such as neuroticism which may have an influence on the association between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization. Substance use was measured with two items only and those items only covered illegal substances, which may have limited the reliability of our findings. Furthermore, we assumed strong MI for substance use even though the configural model showed the best model fit, but produced an error message. In addition, it is important to note that we were only able to assume weak measurement invariance over time for JS and NSSI in the multigroup model that examined the moderator role of sex. Moreover, participants who dropped out from the study reported lower observer and perpetrator JS at T1 than the ones who remained in the study. Although it is a common finding that participants with higher scores on positively evaluated variables remain in longitudinal studies (Gustavson, von Soest, Karevold, & Røysamb, Reference Gustavson, von Soest, Karevold and Røysamb2012), this might limit the generalizability of our findings. Finally, NSSI, substance use, and victimization by peers were only measured at two occasions, preventing to compute a full cross-lagged model between T1 and T2. This, however, also allowed us to examine the sole effects of JS and its effects beyond the stability of problem behavior at the same time. Future research should replicate the present findings, while taking into account further potential relevant variables, such as neuroticism or emotion dysregulation and using a more comprehensive measure of substance use. Most importantly, the moderating role of sex should be re-investigated in larger samples that allow for considering measurement invariance across time and sex for all variables.

The current study is the first to investigate the prospective links between JS, NSSI, substance use, and peer victimization. Findings suggest that being sensitive to injustice-related cues, particularly the tendency to feel unfairly treated or being taken advantage of, could contribute to increasing vulnerability towards self-harming behavior, such as NSSI and substance use, as well as experiencing harming behavior by others, such as peer victimization. It is also important to note that JS can be influenced by these problems in terms of a symptom or a maintaining factor. Clinicians should be aware of the role of victim JS in treatment of these problems and more research is needed in order to examine and understand the effects of and influences on JS in more detail.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421000250

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the German Research Association (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG), Grant No. BO 4482/2-1 and Grant No. GRK 1668/1

Conflicts of Interest

None.