Emergencies are severe disruptions in the functioning of a society. It results from the interaction of hazards with the conditions and characteristics of the community, including the level of exposure, vulnerability, and its existing capacities. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines emergencies as sudden, unforeseen, or expected phenomena that are so severe that require a response from a place outside the accident site. According to the classification, emergencies are divided into 3 groups: natural, human-made, and complex emergencies (CEs). Reference Burkle, Kushner and Giannou1 The third group is a combination of internal strife with large-scale displacement, widespread famine and food shortages, and fragile or falling economic, political, and social conditions. Reference Burkle, Kushner and Giannou1,Reference DeFraites, Hickey and Sharp2

CEs are situations in which a large part of the population is affected by crisis factors such as social unrest, wars, famine, and food shortages, resulting in death, disease, and widespread disability. Reference Keen3 CEs not only increase mortality but also directly increase disease Reference Nielsen, Jensen and Andersen4 and can have significant effects on the public health and well-being of the community. Reference Waldman5 Today, the world is witnessing the most unprecedented CEs that threaten the health of millions of people. In 2014 alone, more than 60 million people left their homes. This is the highest number ever recorded in connection with the homelessness of people due to CEs. Reference Burkle, Kushner and Giannou1

At the time of CEs, 1 of the most critical needs is health care. Reference Waldman5,Reference Stark and Ager6 In this situation, the prompt and appropriate intervention of health-care organizations to organize the affected population are very important and vital. Rapid health assessment is necessary to estimate the extent of the disaster and the facilities needed to ensure the health of the residents in short, medium, and long periods. 7,Reference Murphy, Biringanine and Roberts8 Meanwhile, with the loss of resources and facilities of the communities of low- and middle-income countries, the need for health services is of prime importance. Reference Nielsen, Jensen and Andersen4,Reference Munn-Mace and Parmar9,Reference Connolly, Gayer and Ryan10

Health systems and health-care providers are increasingly affected at the time of CEs and catastrophes. Namely, public health infrastructure is needed to protect civilians and military victims of war. Moreover, we need health-care preparation, and health-care providers that are expert in accident management skills, and triage management in a medical setting. Nonetheless, problems and challenges in CEs were not comprehensively scrutinized in previous studies. Reference Burkle, Kushner and Giannou1–Reference Keen3 Therefore, we decided to systematically review the studies to identify the challenges associated with providing health care in CEs and provide solutions.

Methods

Search Strategy

This study is a systematic review study that collects all previously published information on the challenges of providing health care in complex crises. Various databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, Science Direct, and Google Scholar and Persian databases such as Magiran and SID were searched without a time limit (until December 15, 2020). The websites of organizations active in providing health care in crises (such as the WHO) were also searched.

The keywords used in this review study were a combination of terms related to health-care delivery as well as terms related to CEs. Words related to CEs were selected based on the keywords suggested by Stark and Ager. Reference Stark and Ager6 These keywords were: “Complex emergencies”, “war”, “refugee”, “humanitarian”, and “displaced”. The following terms were also searched for health services: “Health care”, “healthcare”, “health services”, “health system,” “health delivery,” and “health care delivery.” The search strategy was defined by integrating words related to CEs and providing health care with AND indicators (between groups of words) and OR (within each group of words). In addition to electronic search, the reference section of retrieved articles was also examined.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Original studies and research published in English and Persian that address the challenges of providing health care in CEs were included in the analysis. Studies that did not provide health care and only examined mortality and damage from emergencies were excluded. Furthermore, review articles, protocols, comments, letters to the editor, and papers presented in conferences (conference summary) were excluded from the study.

Study Selection Procedure

The review methods were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement on systematic reviews, Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff11 and the steps involved are shown in a PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1). First, the duplicated studies were removed in the Endnote software using Find Duplicates (n = 30). Second, we screened the remaining articles (n = 379). To this end, the titles and abstracts of the articles were obtained and reviewed by 2 authors to ensure their relevance to the study area, which resulted in 32 articles. Next, the full text of these articles (n = 32) was examined to determine their relevance to the purpose of the research which came up with 12 articles. Finally, the remaining articles were evaluated for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skill Program (CASP) checklists, 12 and 6 of them that fulfilled the quality criteria were entered into the systematic review for content analysis to extract the themes (see Table 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1. Characteristics of selected studies for the systematic review

Abbreviation: INGO, international non-governmental organization; US, United States.

Results

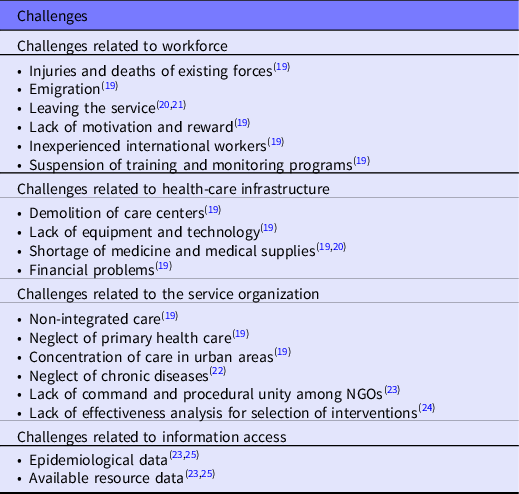

The content analysis of the 6 articles revealed that CEs affect health-care delivery in 4 main areas: workforce, health-care delivery system infrastructure, access to information, and health-care organization (see Table 2).

Table 2. Challenges of health-care delivery in CEs

Workforce

CEs cause fatalities, from which the health forces are no exception. In addition, more doctors and health-care providers are leaving the region in times of complex crises, leaving these service centers (such as hospitals) with severe shortages of the workforce due to the migration. Reference Kevlihan21 Furthermore, due to the fact that promotion programs in times of crisis give their place to immediate responses to the challenges created, the workforce training and performance monitoring system has been severely affected, which can significantly reduce the quality of health care. Reference Bornemisza and Sondorp19

Another major challenge in providing health care in CEs is inexperienced foreign workforces or the lack of experience international forces to provide health care, such as the crisis of the Republic of the Congo in 1999-2000. The majority of health-care workers sent from abroad to provide health care were not adequately experienced and knowledgeable about cholera management leading to an increase in human casualties. Reference Salama, Spiegel and Talley26

Health Infrastructure

Local health centers generally lack proper physical and organizational conditions that can affect all health-care providers at different levels. Furthermore, lack of appropriate health infrastructure severely affects the provision of health care. Reference Bornemisza and Sondorp19 Another major challenge facing health-care providers in CEs is the unavailability or damage to health-care equipment that affects the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. This problem not only causes diagnoses with serious errors but also makes these errors possible in the process of providing medical care and threatens the safety of individuals. Reference Palmer, Lush and Zwi23 CEs bring the loss of resources, of which financial resources are the most important. It is evident that CEs, such as civil wars, lead financial resources toward security and military sectors, which deprive and devour health-care financial support. Reference Bornemisza and Sondorp19

Health Service Organization

Another challenge is related to service organization. Lack of priority leads to focusing solely on infectious diseases in these situations that cause the neglect of noncommunicable diseases. Reference Demaio, Jamieson and Horn22 In particular, due to the lack of available data on cost-effectiveness analysis in health-care delivery during CEs, it causes a significant evidence gap for various health-care interventions. Nevertheless, because of limited resources, decision-makers must have specific priorities based on cost-effectiveness analysis to have the most health achievements with the least resources. Reference Bornemisza and Sondorp19,Reference Palmer, Lush and Zwi23 In addition, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) located in areas with CEs do not operate in unison. This inconsistency and lack of uniformity of procedure may lead to the selection of priorities for intervention (providing health care) not based on the available evidence, feasibility, efficiency, and effectiveness, but by virtue of experience. Reference Palmer, Lush and Zwi23,Reference Boyd, Cookson and Anderson27

Likewise, as mentioned earlier, another challenge is related to neglecting chronic diseases. Too often, in times of CEs, health-care decision-makers and providers prioritize only infectious diseases and ignore the important needs of people with chronic and noncommunicable diseases. Reference Demaio, Jamieson and Horn22,Reference Boyd, Cookson and Anderson27

Information Access

Collecting, managing, and using data related to the health of people in the community as well as health care is one of the main challenges facing the provision of health care in CEs. Although, access to such information, especially in critical situations, is not an easy task. It is crucial to determine the conditions and needs of people, the type of health risks, and the availability of critical resources in CEs. CEs make it difficult to access data and, thus, pose a fundamental challenge to the delivery and management of health care. Reference Palmer, Lush and Zwi23,Reference Thieren25

Discussion

This review study showed that the availability of key information about the epidemiology of health challenges and the resources available to address these challenges is one of the most important and critical issues in providing health care in times of crisis. Probing these challenges is essential for the rapid planning of interventions and defining strategies. Reference Salama, Spiegel and Talley26 This highlights the importance of designing and implementing low-cost epidemiological information systems for low-income areas. Reference Boyd, Cookson and Anderson27 Because of the fact that low-income countries generally face fanatical constraints to even provide basic needs, it is necessary to define a cost-effective plan for health purposes in CEs and determine the efficiency and effectiveness of costs. Reference Deboutte28

First, health-care providers not only should have the experience, technical, and scientific competence to provide health care but also should be familiar with the specific conditions of CEs to make effective and efficient interventions on time. The second important issue is financial challenges in providing health care. Lack of financial resources due to CEs makes the health-care system more dependent on international aid. Reference Mowafi, Nowak and Hein29

Third, in CEs, the focus is only on infectious and acute diseases, while chronic diseases should also be of considerable importance. The importance of diseases such as diabetes or patients with kidney failure who are dependent on dialysis should be prioritized. If these chronic conditions are not managed in crises, they will soon become acute life-threatening conditions. Reference Demaio, Jamieson and Horn22

Finally, organizing and creating a unity of procedure as well as the unity of command among NGOs involved in providing health care in CEs seems to be vital. Otherwise, the limited available resources will become far more limited and scarce in the face of CEs and even maybe squandered by inefficient rework and allocation. Reference Halterman and Irvine18,Reference Rothstein30

Conclusions

CEs are conditions in which a large part of the population is affected by crisis factors such as social unrest, wars, famine, and food shortages, resulting in death, disease, and widespread disability. CEs not only increase mortality but also directly increase diseases Reference Mowafi, Nowak and Hein29 and its effects on public and people’s health are very important and significant, Reference Rothstein30 This study aimed to identify the challenges of providing health care in CEs through a systematic review. The importance of identifying the challenges of health-care delivery in complex crises is becoming increasingly apparent given the fact that low- and middle-income countries are experiencing the most CEs, Reference Munn-Mace and Parmar9 and the care system in these countries has significant weaknesses and challenges.

This review study identified the most important challenges in providing health services in CEs. Planners, designers, and providers of health care, as well as catastrophe management officials, should be aware of these challenges and strengthening the health-care system based on the identified issues. Thus, they can increase the efficiency and effectiveness of interventions in potential crises. Given the fact that the number of studies that examined the challenges of providing health care in CEs is very limited, future studies must inspect the most important challenges through the opinions of all experts and stakeholders in the field.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and editors of Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness for their insightful comments and suggestions on the earlier drafts of this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding source.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest.