The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the routine of health professionals and university students. Reference Mehta, Machado and Kwizera1,Reference Amaral-Prado, Borghi, Mello and Grassi-Kassisse2 Regarding dental education, universities around the world suspended or postponed all face-to-face activities and replaced them by online teaching activities. Reference Wu, Wu, Nguyen and Tran3–Reference Quinn, Field and Gorter5 In Brazilian dental schools, this period was useful for the formulation of new contingency plans to enable the safe return of academic activities, and generate reflections on future clinical practice, research, and university extension. Reference Spanemberg, Simões and Cardoso4,Reference Machado, Bonan, Perez and Martelli6,Reference dos Santos Fernandez, da Silva, dos Santos Viana and da Cunha Oliveira7

Since the start of the pandemic, dentists have been included as a high-risk health professional due to potential risk for COVID-19 cross-infection. Reference Meng, Hua and Bian8–Reference Iyer, Aziz and Ojcius10 A British study observed that, among dental care professionals, dentists have the highest COVID-19 seroprevalence (46.8%), followed by dental nurse (36.2%), and dental hygienist (7.3%). Reference Shields, Faustini and Kristunas11 This is related to the fact that the dentists routinely operate within the aerodigestive tract of patients, performing aerosol-generating procedures, which facilitate the spread of the virus present in saliva. Reference Van Vinh Chau, Lam and Dung12,Reference Allison, Currie and Edwards13 Furthermore, the estimated prevalence rate of COVID-19, among US dentists, was 0.9% (95% CI: 0.5%-1.5%). Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15 This study also showed that dentists who followed interim safety guidelines were well prepared to resume their practice. Reference Estrich, Mikkelsen and Morrissey14 Thus, it is understood that the strict implementation of biosafety protocols during dental procedures is essential to minimize the risks of cross-contamination in clinical practice. Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15

Although dental students are not yet professionals, they perform practical activities in the clinics of their educational institutions and, equally, are exposed to the risks inherent to the profession. Reference Pinelli, Neri and Loffredo16,Reference Jum’ah, Elsalem and Loch17 Therefore, the evaluation of the knowledge of these students about the biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical care during this period can provide important evidence to support the planning and implementation of educational programs, as well as the return of on-site clinical activities, safeguarding the lives of students, teachers, and patients. Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15,Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18,Reference Umeizudike, Isiekwe and Fadeju19 Thus, the aim of this study is to verify the level of knowledge of Brazilian dental students about the biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Ethics Considerations

The target population of this cross-sectional web-based study was composed of dental students from Brazil. This report followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE). Reference von Elm, Altman and Egger20 The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Federal University of Pelotas approved the research protocol for this study (#1413950). All volunteers received clarification regarding the objectives of the study, and those who agreed to participate signed a digital consent form.

Sample Size Estimation

The present study used specific variables from a larger study that investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Brazilian dental education. Reference Fernandez, Vieira and Silva21 Considering that 1 survey evaluated different outcomes, the expected prevalence of the phenomenon equal to 50% was used to obtain the largest sample size. Overall, there are approximately 125 585 students in public and private dental schools unevenly distributed among the different regions of Brazil. 22 The sample size was calculated considering an alpha of 5% and a dropout rate of 30%, so it was estimated that 500 university students were needed for this study. Of those, 36% should be students from the Southeast (n = 180), 16% from the South (n = 80), 10% from the Central-West (n = 50), 9% from the North (n = 45), and 29% from the Northeast (n = 145) Brazilian region.

Logistics of Study and Sample Recruitment

The self-reported questionnaire was developed for the present study. The questionnaire containing the variables included in this study was organized in different thematic sections, which are: (1) sociodemographic factors and related characteristics to educational profile; (2) aspects related to biosafety education, actions adopted by the schools during the pandemic, and sources of biosafety information reported by Brazilian dental students; and (3) variables related to dental students’ attitudes and practices regarding biosafety in dental clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. The complete questionnaire containing the variables for this study is included in Appendix 1.

The survey instrument was hosted on the Google Forms platform and released for responses between July 8 and 27, 2020. Students were recruited through social media advertisements. To this end, the researchers announced the study by sharing the link to the questionnaire on the project’s official Instagram profile (@ensino.odonto_covid19). Invitations were sent electronically to 250 universities/dental schools (public and private) in the 5 regions of Brazil, encouraging institutions to forward the study information to their students. Reference Moraes, Correa and Daneris23 The response rate to the emails was 48.4% (n = 121). Participating researchers shared the official research dissemination post on their personal Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook profiles (feed and stories), as well as asked other dentists to help spread the word about the campaign. Brazilian professors and professionals of dentistry with professional profiles on Instagram were selected by active search on the social media and subsequently invited to share the research invitation post on their individual pages. A total of 248 accounts were contacted through the project profile, and more than half of these contributed to the dissemination of the research (response rate: 75.4%; n = 187). We reached professionals categorized as micro (< 10 000 followers) and meso (10 000–1 million) on the followers’ scale. Reference Boerman24 By the end of the data collection, the project’s profile on Instagram had 1389 followers.

The questionnaire was pretested by a group of masters and doctoral level dental students in 2 public universities in Brazil in a pilot study to verify the feasibility of the instrument. Based on the methods in the previous study, the participants were asked to critically evaluate the clarity, writing, and organization of the items. The volunteers answered the questionnaire, recorded the time required to complete it, and scored the clarity of each item on a scale of 1 (“unclear”) to 5 (“very clear”). The researchers discussed all items attributing a score of ≤ 3 to reach a consensus on how to modify the item based on the volunteers’ feedback. The average time required to complete the questionnaire was 10 minutes. The mean clarity score for all items on the questionnaire was 4.8 (SD 0.50). The present study did not try to validate the used questionnaire.

Variables

The following sociodemographic variables were investigated in section 1: sex (male or female), self-reported skin color according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (white or non-white, black, brown, yellow, or indigenous), age (in years), region (North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast, or South), place of residence (urban or rural), and number of residents in the household. In addition, regarding the variables related to the educational profile, the study considered the type of educational institution (public or private) and the stage of course (in semester) that students were enrolled in. In general, Brazilian dentistry curriculum consists of 10 semesters (5 years) and, for the purpose of statistical analysis, this variable was categorized considering the students’ enrollment according to each year (first, second, third, fourth, or fifth year).

The second section verified whether the students had already received biosafety guidelines for aerosol control in the dentistry course before the pandemic (yes or no). In addition, the main teaching methodology adopted by schools during the pandemic (interruption of all teaching activities or distance learning) was collected. The participation of students in additional training methods on biosafety that should be adopted in a clinical setting during this period (no type of training, theoretical training, or theoretical-practical training) was collected. Three different variables were used to check the source of information regarding biosafety measures. The available sources of information were: (1) scientific literature; (2) documents from regulatory agencies (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária—Anvisa, Ministry of Health, Federal Council of Dentistry); and the (3) Internet (websites, blogs, and social networks) (yes or no—for each variable).

The third section verified the students’ knowledge about the basic biosafety measures that should be a dental clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. This section was structured from the presentation of a brief introduction, followed by 8 affirmative sentences organized in 1 block. The sentences were elaborated through a previous bibliographic survey performed by the researchers and encompassed the main changes in the biosafety protocols in dentistry published by regulatory agencies in the world in this period, 25–27 particularly in Brazil. 28–Reference Vieira, Pedrotti Moreira and Mondin31 For each sentence (variable), 2 answer options were available: yes (agree) and no (disagree). For all questions, the correct answer was “yes,” except for the second and third variables. For each corrected answer, 1 point was attributed, and incorrect items were given a 0. Based on that, the main outcome of the present study was composed, which considered the sum of correct sentences, ranging from 0 to 8 points.

For all variables in sections 1 and 2, the following response options were available: “I would rather not say” and “Does not apply.” During data analyses, these answers were considered as missing data. Regarding section 3, no missing data were detected, as all 8 questions were answered adequately. For these variables, we did not perform data imputation, but the participants were included in the analysis.

Data Analysis

A symmetrical distribution of the sample was observed for the primary outcome of this study by visual analysis of a histogram. The descriptive analysis of the variables was observed from the distribution of absolute and relative frequencies, central tendency (mean), and variability (standard deviation). To verify the factors associated with the mean knowledge score about the basic biosafety measures that should be adopted in dental clinical scenario (dependent variable), the following independent variables were considered: gender, skin color, age, region, place of residence, number of residents sharing the house, type of educational institution, course stage, biosecurity guidelines for aerosol control before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching methodology adopted by the faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic, participation in training on biosecurity measures that should be adopted in dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and sources of information used in the guidelines for biosecurity measures that should be adopted in clinical care. Multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to verify the association between dependent and independent variables, and variables that presented P ≤ 0.20 in the bivariate analysis were included in the initial adjusted analysis. The maintenance of the independent variables in the final model was determined by the combination of P < 0.05 value and the analysis of effect changes. In addition, multicollinearity analysis was performed, and none were observed. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPPS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The graphical representations were produced using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.1.1; San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

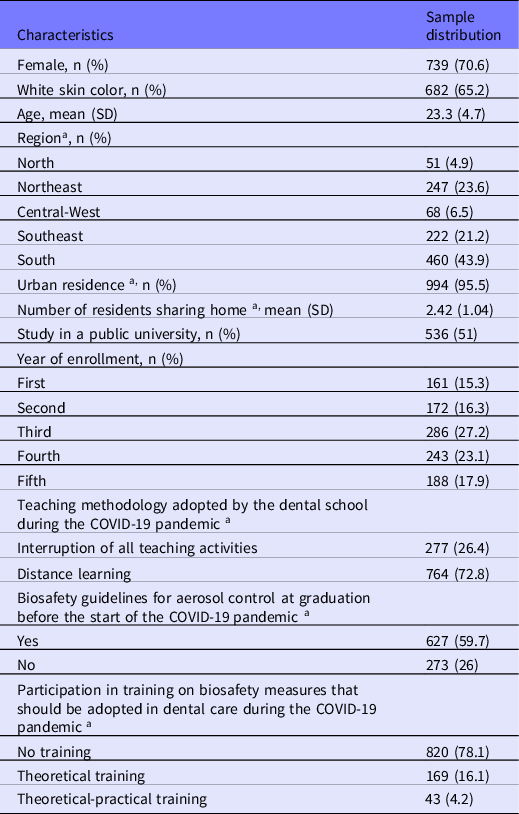

A total of 1050 dental students responded to the questionnaire. In general, most participants were female (70.6%), reported being white (65.2%), with a mean age of 23.3 (SD 4.7) years. Most of the students who participated in this study lived in the South (43.9%) and Northeast (23.6%) regions of Brazil. Almost all of the sample lived in the urban area and shared the home space with 2.4 (SD 1.0) people. The distribution of students regarding the type of educational institution was similar, as 51% of them were enrolled in public schools. The majority of the students (68.2%) were in the intermediate or final stage of the degree course (third, fourth, or fifth year) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Brazilian dental students and aspects related to biosafety education, teaching strategies adopted by the dental schools, and history of participation in biosafety training in the pandemic (n = 1050)

a Variable with missing data.

The main teaching method adopted by the faculty during the pandemic was distance learning (48.5%). More than half of Brazilian dental students had already received biosafety guidance for aerosol control before the COVID-19 pandemic (70%). However, more than two thirds of the participants had not been trained in biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the pandemic period (69.5%). Among the trained students, approximately 16.4% and 4% of them received only theoretical and theoretical practical training, respectively (see Table 1).

Figure 1 illustrates the main sources of information on biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic used by the participants. The block of variables that checked dental students’ knowledge of biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic is described in Table 2. The highest frequency of correct answers was observed for questions #1 (91%), #4 (90.2%), #6 (84.4%), and #8 (87%). Only 20 dental students (1.9%) correctly answered all variables.

Figure 1. Sources of information on biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 1050).

Table 2. Variables related to dental students’ knowledge regarding biosafety in dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 1050)

The average score of correct answers about biosafety measures that should be adopted in university clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic per student was 5.29 (SD: 1.28). The mean distribution of the knowledge score according to general characteristics and aspects related to biosafety education, actions taken by dental schools during the pandemic, and sources of biosafety information reported by Brazilian dental students can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Distribution of the mean score of knowledge about attitudes and practices regarding biosafety in dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic according to the study variables (n = 1050)

x ¯, mean; SD, standard deviation; * T-test unequal; # One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The highest mean score of biosafety knowledge was significantly associated with the following variables: sex, skin color, stage of course, teaching methodology adopted by the faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic, biosafety orientations for aerosol control in the undergraduate course before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and participation in training on biosafety measures that should be adopted in dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic (P ≤ 0.05) (Table 4). After adjustments for potential confounders, it was observed that female students (β = 0.348 [95% CI: 0.155, 0.542]; SE: 0.985; P < 0.001) enrolled in the fourth (β = 0.527 [95% CI: 0.158, 0.896]; SE: 0.187; P = 0.005) or fifth (β = 0.569 [95% CI: 0.188, 0.949]; SE: 0.949; P = 0.003) year of the undergraduate course in dentistry, and who have participated in theoretical-practical on biosecurity measures to be adopted in dental care in the pandemic (β = 0.489 [95% CI: 0.082, 0.895]; SE: 0.207; P = 0.009) remained significantly associated with higher knowledge score about biosafety. Students who had not received guidance on aerosol control in practice setting before the pandemic had the lowest knowledge score (β = −0.328 [95% CI: −0.523, −0.132]; SE: 0.099; P < 0.001).

Table 4. Bivariate and adjusted linear regression of the knowledge score on attitudes and practices regarding biosafety in dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic according to the general characteristics and aspects related to biosafety education, actions adopted by the dental schools during the pandemic, and sources of biosafety information reported by Brazilian dental students (n = 1050)

ref., reference; β, Beta coefficient; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; SE, standard error; -, variable not included in the final adjusted analysis.

Discussion

This study evaluated the knowledge of Brazilian dental students about biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings showed that the students have a medium level of knowledge about the biosafety measures, the most of them answered correctly less than two thirds of the proposed questions. Approximately less than 2% of respondents answered correctly all of the questions. The highest average score of knowledge about biosafety was observed among female dental students, those enrolled in the intermediate or final stages, those with prior knowledge of aerosol spread containment measures, and those who had already received theoretical-practical training in dental biosafety in the pandemic.

Biosafety Measures in Clinical Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic

National and international guidelines existed before the COVID-19 outbreak to prepare dental staff for the different biological risks inherent to the profession. Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15 In the last decade, cross-sectional studies conducted in non-pandemic periods have reported that Brazilian dental students have sufficient and appropriate knowledge and attitudes to avoid contamination and cross-infection risks in clinical practice, especially in aspects related to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), performance of the disinfection process, and the use of surface barriers. Reference Pimentel, Batista Filho, Santos and Rosa32–Reference Arantes, de Andrade Hage, do Nascimento and Pontes35 However, some previously published protective measures are not effective in preventing the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15

Faced with the global context of public health emergency, new guidelines have been established to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and any other pathogens in a clinical setting. 25–Reference Thomé, Bernardes, Guandalini and Guimarães29 In addition to increased personal protection with PPE use, changes in primary patient screening, care delivery, and dental clinic infrastructure were also included in the new care protocols. Reference Silveira, Fernandez and Tillmann15 Recently, a web-based study conducted during the pandemic found that Brazilian dental students were familiar with some preoperative preventive measures. However, specific measures to prevent or decrease aerosol generation have been less recognized as a measure to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18

Other studies also evaluated the knowledge of biosafety aspects in the pandemic of COVID-19 among dental students in Asian/Middle Eastern (Iran Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36 and Turkey Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37 ) and African (Nigeria Reference Umeizudike, Isiekwe and Fadeju19 ) countries. Although the findings of these studies showed that students have acceptable response rates regarding the correct biosafety measures to prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a clinical setting, the results reflect the need for the expansion of knowledge related to the disease, Reference Umeizudike, Isiekwe and Fadeju19 and about the extra biosafety measures that should be performed by students in the dental routine. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18,Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36,Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37

Comparisons between the findings of the present study and recent reports are limited by differences in the presentation and selection of biosafety procedures among the studies. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18,Reference Umeizudike, Isiekwe and Fadeju19,Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36,Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37 Despite that, similar information may be retrieved from a study with a Turkish sample, Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37 as both studies demonstrated that students understand the importance of primary screening to identify potential SARS-CoV-2 patients. Conversely, the present study considered the remote modality as the main learning method, while the Turkish study encompassed this step as part of face-to-face care. Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37 Interestingly, this finding contrasts with the fact that most Iranian dental students did not recognize the role of initial screening (face-to-face) in preventing coronavirus transmission at dental departments and clinics. Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36

Erroneously, Brazilian dental students in our study agreed that clinical sessions for periodontal maintenance and prosthetic adjustments are elective emergency procedures for dental treatment during the pandemic. Emergency treatments involve the presence of intense painful symptoms and require immediate intervention for pain relief, as in cases of traumatic dental injury, pericoronitis, abscess, or localized bacterial infection. 25 Thus, as recognized by Turkish students, patients with clinical pictures that stimulate the presence of intense pain are eligible for dental treatment in the pandemic, Reference Ataş and Talo Yildirim37 which differ from the elective treatment listed in the questionnaire of the present study.

Because of their ability to reduce the number of microorganisms in the oral cavity, Reference Marui, Souto and Rovai38 antiseptics have been used as a standard measure before dental treatment, especially in the pre-operative stage. Reference Dominiak, Shuleva, Silvestros and Alcoforado39 When used in adequate concentrations and time, different solutions, such as Povidone-Iodine (PVP-I), Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2), and Cetylpyridinium Chloride (CPC) are also capable of reducing the viral load of certain strains, such as the human coronavirus. Reference Vergara-Buenaventura and Castro-Ruiz40 In this study, less than a third of the sample recognized mouth rinsing with PVP-I (0.02%, 0.04%, 0.05%—9mL; 30 seconds) as a pre-procedure measure in the pandemic. Nevertheless, a low frequency of perception about the need for mouthwash was also seen in previous studies conducted with Brazilian and Iranian students in the pandemic. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18,Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36 This finding reinforces the need for wide dissemination about the importance of mouth rinsing and the use of appropriate pharmacological substances among dental students. Reference Vergara-Buenaventura and Castro-Ruiz40 Evidence shows that the use of commercial mouthwashes with H2O2, CPC and PVP-I can be useful as a pre-procedure conduct, Reference Seneviratne, Balan and Ko41 influencing in the reduction of cross-contamination in clinical practice. Reference Vergara-Buenaventura and Castro-Ruiz40,Reference Langa, Muniz and Costa42

Contaminated aerosols and droplets can be produced from saliva and blood during different dental procedures, from drying the dental element for anamnesis, during intraoral X-rays, even in more complex procedures, such as the removal of decayed dental enamel using a high-speed handpiece and air syringe, and in the ultrasonic irrigation of the root canal. Reference Yang, Chaghtai and Melendez43,Reference Azim, Shabbir and Khurshid44 Effective measures to prevent or minimize the production of COVID-19 contaminated droplets or aerosols in the dental office are well documented in the literature. 25,28,Reference Thomé, Bernardes, Guandalini and Guimarães29 Among these, the 4-hand technique, for example, is considered beneficial for infection control. In addition, the use of manual instruments (where applicable), rubber dams, and high-powered salivary suckers can significantly reduce the production and dissemination of airborne particles in clinical practice. 25,Reference Yang, Chaghtai and Melendez43 It is important to highlight that taking radiographs with intraoral techniques may stimulate microbial expulsion in aerosols Reference Vandenberghe, Jacobs and Bosmans45 and, therefore, extraoral techniques, such as dental panoramic radiographs (DPR), and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), may be suitable alternatives to be used in the outbreak of COVID-19. Reference Meng, Hua and Bian8,Reference Thomé, Bernardes, Guandalini and Guimarães29

Our findings showed that the assistance of another operator in infection control during dental procedures (4-hand technique) in the pandemic was not a conduct recognized by a representative portion of dental students. In addition, more than one third of the participants were not aware of the need to use manual instruments, protective rubber barriers, and powerful sucker during these procedures, which is in accordance with previous national Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18 and international Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36 findings, which identified a low adherence of these accessories as a strategy to prevent the dissemination of COVID-19 by dental students in procedures that generate aerosol. Still, it is noteworthy that almost half of the students in this study disagree on the use of extraoral techniques to replace intraoral modalities during the pandemic, which could avoid the dissemination of contaminated droplets. It is essential to consider that, although DPR may replace intraoral radiographs in specific diagnoses during these difficult times, CBCT is associated with higher radiation doses and cost, and its use as an alternative to intraoral technique should be employed with extreme caution. Reference Dave, Coulthard and Patel46

The need to wear a PPE set during dental care, such as gloves, disposable cap, surgical mask overlapped by masks N95/PFF2 or equivalent, face shield, and capote or apron with long sleeves and waterproof, was reported by most students in this study. This finding corroborates pre-pandemic records that demonstrate a satisfactory rate of PPE use among Brazilian dental students, Reference Zocratto, Silveira, Arantes and Borges47,Reference Abreu, Lopes-Terra and Braz48 and matches the global perspective of previous reports with similar samples that also showed satisfactory levels of perception about the use of different PPE in clinical dental practice during the pandemic. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18,Reference Esmaeelinejad, Mirmohammadkhani and Naghipour36

The readjustment of the infrastructure of university clinics, especially regarding the spacing and isolation of dental units and the control of air circulation, is one of the great challenges of dental schools during the pandemic. Reference Machado, Bonan, Perez and Martelli6,Reference dos Santos Fernandez, da Silva, dos Santos Viana and da Cunha Oliveira7,Reference Vieira, Pedrotti Moreira and Mondin31 In Brazil, most universities have dental care units distributed in the open-plan clinics format (ie, multiple chairs in 1 clinical area with only modest dividing walls that do not reach the ceiling). Reference Machado, Bonan, Perez and Martelli6,Reference dos Santos Fernandez, da Silva, dos Santos Viana and da Cunha Oliveira7 In these environments, there is a higher risk of cross-infection, due to the dissemination of pathogens through the concentration of aerosols from the various dental procedures performed simultaneously, as well as due to the high turnover of students, employees, and patients in these facilities. Reference Meng, Hua and Bian8,Reference Peng, Xu and Li9,Reference Holliday, Allison and Currie49

Current protocols reinforce that the old community clinic model should ideally be replaced by individualized care boxes. Reference Meng, Hua and Bian8,Reference Costa, Branco and Vieira30 If this is not possible, the collective care spaces should be reorganized with adequate distancing and use of mechanical barriers between dental chairs, as well as equipment to perform air filtration and flow. Reference Costa, Branco and Vieira30 In the present study, most students recognized the need to adapt the infrastructure of university clinics to the new biosafety reality of the post-pandemic period.

Associated Factors Related to Knowledge in Biosafety Measures in Clinical Setting

Several studies have explored the influence of gender differences on the academic performance of dental students. Reference Stewart, Bates, Smith and Young50,Reference Silva51 Currently, there is a trend toward the feminization of dentistry Reference Kfouri, Moysés and Gabardo52 that may be accompanied by the better performance of women in academic assessments, Reference Silva51 which is related to traditional notions (in the context of culture and biopolitics) of a natural feminine inclination to care and be sociable with other people. Reference Silva51,Reference Kfouri, Moyses and Moyses53 This knowledge may explain why female dental students had a significantly higher mean score of knowledge about biosafety measures than male students in the present study. In the pre-pandemic period, better practices of infection control and academic performance among female dental students have been demonstrated. Reference Silva51

Students enrolled in the final stages (fourth and fifth years) of the dental degree course had higher average knowledge about biosafety measures in the present study. This finding may be related to the fact that these students have a greater load of theoretical knowledge and clinical experience than those in the initial stages. Reference Stewart, Bates, Smith and Young50,Reference Silva51 Moreover, this difference may be related to the students’ increased expectation to return to clinical practice and a deeper concern to finish their reports and qualifying exams, reflecting their need of learning more about COVID-19 and biosafety measures. Reference Umeizudike, Isiekwe and Fadeju19,Reference Loch, Kuan and Elsalem54

In the present study, dental students who received instruction on aerosol control measures during their course prior to the pandemic onset, as well as those who participated in theoretical-practical refresher training on biosafety guides during the COVID-19 pandemic, had higher mean knowledge scores than those who had not received such guidance. This finding was not unexpected, as greater access to adequate biosafety information directly justifies this relationship. In any case, it is interesting to note that a representative portion of students did not receive guidance on aerosols, and more than two thirds of the participants were not trained on biosafety measures in the pandemic.

In this context, the analysis of this panorama reflects the need for Brazilian dental schools to use available resources to train their students on the biosafety protocols in force, ensuring safe academic return. Reference Aragão, Gomes, Pinho Maia Paixão-de-Melo and Corona18 Although, at this time, the extensive practical training of students is limited by the pandemic containment measures, it is feasible to use virtual learning environments for the dissemination of reliable guidelines that can decrease or stop the cross-transmission of diseases in the clinical practice. Indeed, the use of the e-learning modality proved to be a successful adjunct and impacted the environment in which dental students learn, promoting a more efficient productive routine with higher levels of engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reference Hattar, AlHadidi and Sawair55

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The adoption of an innovative method of online data collection and dissemination through social media, which is an especially useful research tool and a promising method in times of social isolation, is one of the main strengths of this study and deserves to be highlighted. Reference Moraes, Correa and Daneris23 Furthermore, up to date, this is the first Brazilian study that provides evidence on the knowledge of dental students about the current biosafety measures that should be adopted in clinical practice during the pandemic of COVID-19. Considering the important contribution that Brazil offers to dental research and education, our findings are essential to support teaching activities aimed at training students to return to clinical practice, especially by directing educators and managers on which student groups should intervene.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, considering some limitations. The first involves the cross-sectional design of the study, as this does not allow cause-effect relationships to be established. Second, the regional differences in the distribution of students showed that most of the sample were not from the region of the country where the largest number of dentistry courses are located (Southeast). Finally, the use of a non-validated research instrument can be listed as a limitation of this study, although it is able to provide important knowledge about the population at this time of pandemic crisis. However, the questionnaire was previously tested by a group of dental students to increase its applicability. Moreover, all associations between the variables of the present study are considered valid and robust.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that Brazilian dental students have a medium level of knowledge about the biosafety measures that should be adopted in dental clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, sociodemographic characteristics and those related to the institutional profile of the participants, as well as access to guidance and training in biosafety, can influence the level of knowledge of students. It is interesting that dental students do not know basic biosafety measures, which, regardless of the pandemic, should be adopted, which reflects the risk of their exposure to cross-infection in the clinical setting when resuming face-to-face activities. Thus, we encourage institutions to use online teaching activities to expand students’ knowledge about biosafety protocols, ensuring a safe academic return for students, teachers, and patients.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2022.9

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all Brazilian dental students who participated in this study, as well as professors and other collaborators who helped disseminate the research on their social networks and institutions.

Funding statement

MSF holds a scientific initiation FAPERGS (Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio Grande do Sul [Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul]) scholarship for undergraduate students (Project 2019/2020-10133). This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES). The authors self-funded the other part of the study.