Wildfires in California have increased in frequency, area burned, intensity, and duration over several decades but most notably in the past 3 years. Multiple factors are associated with this increase, including fire and forestry management practices, land utilization, changes in climate resulting in warmer temperatures, drier summers and fuels, below-average winter precipitation or earlier spring snowmelt, and an increase in the length of the wildfire season. Reference Masri, Scaduto, Jin and Wu1–Reference Westerling, Hidalgo, Cayan and Swetnam3 In 2020, California experienced the largest number and size of wildfires in state history. There were 9639 individual fires that burned a total of 4 397 809 acres, equal to 4% of the total area in the state. The 2020 fires included 5 of the top 6 largest fires in California since accurate records began in 1932, and the first fire that burned over 1 million acres (August Complex). At the height of the 2020 “Fire Siege” in late September, approximately 18 500 firefighters were engaged in firefighting operations. Between 100 000 and 200 000 persons were evacuated at any given date during the latter part of August 2020, complicated by the need for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) public health preventive measures. Twenty-eight civilians and 3 firefighters lost their lives in these fires. Reference Morris4

Organization of Disaster Medical and Public Health Services in California

In California, the state emergency management agency is the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (OES), which has overall responsibility for coordination and management of disaster services. 5 For optimal efficiency, emergency response services are divided into functional areas called Emergency Support Functions (ESF), closely aligned to the federal ESFs delineated in the National Response Framework. Public Health and Medical response (ESF-8) is delegated to a collaboration between the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and the Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA), both within the California Health and Human Services Agency. EMSA specifically has statutory responsibility to coordinate disaster medical responses.

All state agencies must organize disaster services under the Standardized Emergency Management System (SEMS), which is consistent with the National Incident Management System (NIMS). 6,7 Key principles include primary responsibility for response at the level of the local jurisdiction with resource support escalating to higher levels of jurisdiction and use of the Incident Command System (ICS). 8 For health and medical resources in California, requests go through the local (county) Medical and Health Operational Area Coordinator, who is the public health officer or emergency medical services (EMS) director, to a Regional Disaster Medical and Health Specialist (CA Health and Safety Code § 1797.150-153) and then to the state ESF-8 agency representatives or duty officers. These levels all communicate as soon as a disaster occurs to ensure rapid health and medical response. Requests for ESF-8 resources may also come directly to OES and be referred to the agency representative within the State Operations Center (SOC). During the height of COVID-19 medical surge requests, an ESF-8 multi-agency coordination (MAC) group was active in the SOC to approve and prioritize requests. Even if approved, some requests were modified, for example, the number of health care staff requested. EMSA is consulted concerning appropriate missions and is tasked with a mission if it is within the capabilities and resource capacity of the agency. One exception is for medical aid stations within fire incident base camps that are under prior interagency agreement (see below).

To deploy teams to the field, EMSA augments its limited full-time staff with California Medical Assistance Teams (CAL-MAT) members. CAL-MAT is modeled after the federal Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMAT) Program. When activated, CAL-MAT members become temporary California State employees through emergency hire, which provides a stipend based on their role, liability coverage, and workers’ compensation. Members are rostered in advance in the Disaster Healthcare Volunteer (DHV) system that was developed as part of the federal Emergency System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals (ESAR-VHP). 9 The DHV system maintains professional credential, references, work history, and verifies professional licenses through electronic links with professional licensing boards. 10

CAL-MAT volunteers are organized in regional units that ideally meet regularly, conduct training in clinical, logistical, and fire camp operations, and prepare for deployments; however, orientation and training were recently compromised due to urgent large staffing needs to support COVID-19 medical surge as well as wildfires. Most medical personnel have other regular employment, and their position is protected by law while they volunteer for these missions. Personnel are asked to deploy for a standard 14-day tour, optimally with the ability to extend.

(See Rymer T, Breyre A, Lovett-Floom L, et al. California Medical Assistance Teams (CAL-MAT): disaster teams rapid expansion, adaptability and innovations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. In review.)

Discussion

Medical Response to Wildland Fires

EMSA uses multiple disaster resources to provide 3 main areas of medical support for wildland fires: (1) the evacuation of patients from facilities and movement to safe facilities or shelters, (2) direct medical care to displaced populations within shelters and support for medical surge within the medical community, and (3) medical support for firefighters and all personnel within incident base camps.

Support and Evacuation of Medical Facilities

The first priority during a wildfire is rescue of dependent victims who may become trapped by the fire. In the 2018 Camp Fire, 85 residents were killed trying to shelter in place, primarily elderly persons residing in private homes without a means of self-evacuation. Health facilities in fire evacuation zones must be evacuated. This includes not only acute care hospitals but also long-term care, skilled nursing facilities, and other congregate living where residents cannot self-evacuate. The local Emergency Medical Services agency (LEMSA), in coordination with the local emergency management agency and public health, provides support for facility evacuations. However, hospital evacuation in addition to a surge in 911 calls requires additional EMS resources that respond from neighboring jurisdictions.

California has a system of ambulance strike teams that are routinely used in earthquakes, fires, and other multi-casualty incidents. 11 These consist of 5 ambulances of like type (Basic Life Support or Advanced Life Support) with a leader unit to provide resupply and communications. Initial ambulance strike teams attempt to reach the site within 2 hours but may take up to 6 hours, depending on the location, with other teams arriving shortly thereafter. The goal is to transfer patients or residents to a similar type of facility. EMSA has developed a comprehensive patient movement plan for any type and scale of incident. 12 A planning guide and checklist are available as part of the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS) for a facility emergency management program and disaster operation center to coordinate emergency evacuation decision making and operations. 13–Reference Krilich and Currie15

Wind-driven fires, especially during “red flag” conditions, may not allow for an orderly evacuation of medical facilities, 16,Reference Adini, Laor, Cohen and Israeli17 so health care facility staff act to move patients out of the facilities and load them into any emergency vehicles, buses, vans, or private vehicles available without waiting for dedicated EMS resources and without confirming accepting facilities. Evacuation by staff is frequently done for small residential care facilities, but it is unusual for general acute care hospitals (GACHs); however, this approach was necessary for GACHs in both the 2017 Napa-Sonoma Tubbs Fire and in the 2018 Camp Fire that swept through Paradise California. Reference Hick, Weil, Skivington and Saruwatari18,Reference Gabbert19

Health care facilities not directly threatened by fire may be impacted by smoke or by loss of power. Air purifiers and generators are the first solution, but if these are not sufficient to provide a healthy environment, patient evacuation is implemented.

A critical planning and response function for the public health or health agency is to rapidly determine the status of all types of licensed facilities from acute care to home residential care, which can be very challenging in the initial chaos after a large emergency, especially if communications are disrupted. One method is for facilities to report their status directly to the public health and medical emergency operation center or health branch. In California, facilities report to a local or regional medical and health coordinator in either the local public health or EMS agency, which then reports the data to the State Medical and Health Coordination Center. When a facility does not report, direct outreach to a key facility contact is necessary. The California Department of Public Health generates a Geographic Information Systems map with the boundaries of the disaster and overlays of each type of health facility. A dashboard tracks facility operational status, status of their patient population, and repatriation status if evacuated. This is updated frequently and includes facilities licensed by both the Department of Public Health and the Department of Social Services. 20 Repopulation can only occur after evaluation of both structural and operational capability. 21

While it is most efficient to evacuate to nearby facilities to avoid prolonged transports, it can be challenging to predict the subsequent course of a fire. In 2017, about 240 patients were evacuated from a state residential developmental center to a community center in the nearby town of Sonoma, which subsequently was ordered to evacuate from the Tubbs fire in Napa and Sonoma counties. Residents were then moved to a fairgrounds 45 minutes away where a long-term care/skilled nursing facility was established within exhibition buildings. Individual medical needs required evacuation of specialized beds, wheelchairs, and medical equipment for many of the patients. A factor key to the success of this evacuation was the dedication of the staff who evacuated with the residents and maintained continuity of care. Reference DaSilva22

Shelter medical care

Fires often force the rapid evacuation of entire towns and surrounding areas to general population shelters. Some level of medical care is always required. If a shelter has received large numbers of elderly or residents of local care facilities, medical needs may exceed the first aid level provided in most American Red Cross shelters. During the 2018 Camp Fire, EMSA CAL-MAT teams supported 12 sites with the highest medical needs in collaboration with local organizations or American Red Cross providing the shelter management. In other shelters, local public health or American Red Cross supported basic medical needs. The most common medical need is for replacement of prescription medications that were left behind during rapid evacuation. California has statutory language allowing pharmacies to refill medications without a new prescription (Bus. & Prof. Code 4062 and Health & Safety Code 11167). There is also a federal program that can be activated to provide prescriptions free of charge to disaster victims. 23

When shelters are established, public health should engage early to assure appropriate hygiene and disease surveillance. Measures to control outbreaks of norovirus in the Camp Fire shelters included separate isolation tents for affected residents as well as improvement of hygiene within the shelters and an increase in the number of portable toilets and hand-wash stations. More recently, COVID-19 necessitated a new approach to shelters, moving from the traditional congregate shelter to separate hotel rooms or tents (Figures 1-2).

Figure 1. Congregate shelter, Camp Fire (2018).

Figure 2. Shelter with physical separation for families during COVID-19 pandemic, 2020.

One common challenge to providing medical care is locating personal health information when treating patients outside of their usual health facilities or health care systems. EMSA has developed a health information exchange interface that allows volunteer medical providers to access patient records across multiple health systems. Patient Unified Lookup System for Emergencies (PULSE) is activated during an emergency and allows verified disaster medical volunteers to use web access to obtain personal health information. PULSE queries multiple regional health information organizations and health systems, Surescripts (for medication history), and other health information repositories, then summarizes the findings in to a continuity of care document that includes medical history, allergies, problem lists, medications, and other key data. 24

Smoke from wildfires is one of the public health issues that impacts the entire community as well as the responders. There is significant recent research on the health impacts of smoke on the public and on firefighters. The Air Quality Index (AQI) closely monitors smoke from California fires. It is often very high in adjacent states and has even impacted air quality on the East Coast of the United States. A report from CDPH provides guidance for public health officials. 25

Medical Support for Fire Responders

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) provides direct fire suppression as well as other emergency services within the State Responsibility Areas and in 36 of California’s 58 counties through a system of cooperative agreements with local governments. CAL FIRE coordinates with other agencies when the fires involve military, federal, tribal, or local jurisdictions.

EMSA is contracted by CAL FIRE through an interagency agreement to provide medical care in fire incident base camps to firefighters, emergency managers, vendors, and others who support the response. Major fire incident base camps involve thousands of personnel and provide services to firefighters who work in shifts and return to camp either at night or in the morning after a long period of intense physical work in extreme heat and smoke. Due to the unique needs of firefighters, the limited resources available at remote fire camps, and the need to have an emergency medical team on site, a request to EMSA for medical support is routinely initiated when CAL FIRE deploys 1 of their 6 Incident Management Teams (IMT). This is done if a fire is exhibiting extreme behavior or if it continues to spread and requires significant additional resources.

CAL FIRE and EMSA both organize according to the ICS. Within a fire incident base camp, the medical unit operates under the Medical Unit Leader (MEDL) within the logistics section. The MEDL may have EMS training but is not typically a medical provider. In consultation with the Chief Medical Officer at the site, the CAL FIRE MEDL manages the disposition of firefighters who require medical evaluation or transport for medical care off site. CAL-MAT field missions are managed under the EMSA Operations section, since EMSA is directly running the health care response.

The typical CAL-MAT fire incident base camp team consists of 9 to 11 medical personnel: 1 physician, 1 non-physician provider (a nurse practitioner or a physician assistant), 1 to 2 nurses, and 6 to 8 emergency medical technicians (EMTs) or paramedics. The medical team works in 12-hour shifts (day/night) with most of the staff working during the day shift. Fire personnel may present for medical evaluation at any time depending on when they are back at the incident base; the busiest times are the early mornings and evenings. Demand for services during the night is low, so staffing can be limited to 2 EMTs or EMT and nurse with a provider on call. In the rare event that a physician is not on site, the non-physician providers are encouraged to consult with an on-call physician.

EMSA deploys an administrative liaison to the camp to coordinate support for the medical team and to interface with the CAL FIRE IMT. A support structure at EMSA headquarters handles personnel, human resources, supply logistics, and other administrative functions for the medical team that cannot be managed at the fire camp.

Fire cache trailers are pre-loaded in anticipation of deployment to incident base camps, except for pharmaceuticals that are securely maintained and added to the trailer prior to departure. Original trailers measured 7x10x6 feet but were packed too tightly with no space for additional items, so new trailers are being purchased that measure 8x14x8 feet. The trailers contain enough items to sustain a medical response for at least 72 hours, including all medical supplies, chairs, tables, biomedical equipment (such as monitor-defibrillator), and patient cots (see Supply Logistics section). Mobilization of equipment and personnel is expected within 24 hours of a mission request. The median mission length for 2020 deployments was 14 days, with a range of 4–30 days.

The 20- by 40-foot tents that house the medical equipment, isolation area, and personnel sleeping quarters are set up ahead of time at the camps by CAL FIRE, but CAL-MAT teams set up the equipment within the tent (Figure 3). The current formulary and equipment list is available in the online Appendix. Changes can be made with the agreement of the CAL-MAT and CAL FIRE Medical Directors.

Figure 3. Medical tent.

The CAL-MAT medical team evaluates and treats firefighters and other support personnel for common ambulatory medical problems and emergency treatment within the incident base camp. Reference Backer, Wright, Dong, Baba, McFadden and Rosen26 CAL-MAT personnel also can perform return-to-work evaluations after initial treatment and recovery. The equipment and formulary list for the medical unit is available online (Appendices A, B). In addition to standard vital signs, diagnostic capabilities include serum glucose, electrolytes and renal function using iSTAT Chem 8 panel cartridge (Abbott), COVID-19 testing with Binax antigen test and ID NOW (NAAT test, Abbott), pregnancy test, and streptococcal antigen test. There is no x-ray capability. A cardiac monitor/defibrillator (Zoll X series) provides cardiac monitoring capability as well as 12-lead electrocardiogram.

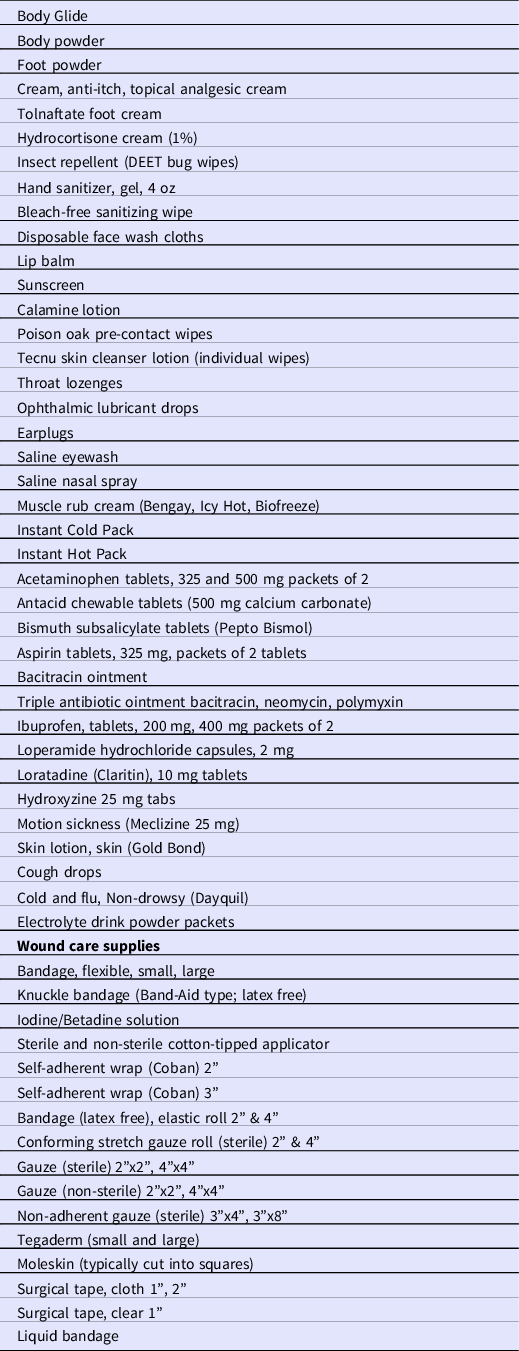

Another function of the medical team is to provide common over-the-counter products to fire personnel, such as skin cream and powder, pre- and post-exposure poison oak medication, insect repellent, eye wash, lip balm, sunscreen, and certain non-prescription medications (Table 1). These preventive or self-care items are dispensed on request without requirement for a provider consultation. This enables easy access to common personal care products for personnel while not depleting the stock available to residents in sparsely populated areas.

Table 1. Dispense on request items from CAL-MAT medical tent to firefighters at incident base camp

Rarely are patients seen outside of the medical tent; however, a portable bag with Advanced Life Support (ALS) equipment with an automated external defibrillator is kept in the tent to respond to medical emergencies within the incident base camp. Additionally, each incident base camp maintains an ambulance on site from the local jurisdiction, and pre-positioned EMS resources (“line medics”) near the fire lines to transport serious injuries directly to an emergency department based on local protocols. Air evacuation from the fire line may also be an option for life-threatening injuries or with prolonged ground transport time if conditions allow.

Operational Challenges During the 2020 California Fire Season

During the 2020 California fire season, A total of 248 personnel were deployed to 23 different wildfire incident base camps. As with any disaster response, many unanticipated challenges were identified during these deployments. A few are noted in the following sections.

COVID-19

The fire season of 2020 occurred during high levels of COVID-19 transmission in California and prior to arrival of a vaccine. Firefighters work in close-knit engine and strike teams in which social distancing is difficult as they travel and eat together and sleep in common quarters. CAL FIRE established protocols for social distancing at the incident base camps but distancing and masking are difficult to maintain and enforce. Protocols for testing and managing of persons under investigation (suspected cases awaiting test results) were jointly developed by the medical directors of CAL FIRE and CAL-MAT. During the season, CAL-MAT acquired the ability to perform testing with both a rapid antigen test (Binax, Abbott) and a confirmatory molecular test (ID NOW, Abbott). A separate tent was designated at each site for short-term isolation of symptomatic individuals or to closely monitor the rest of the team without demobilizing an entire strike team of firefighters if 1 individual was suspected of being COVID-19 positive. The tent was used for 15 firefighters, and another 27 were isolated in a hotel room for suggestive symptoms over the 2020 fire season. One of the most common reasons to demobilize a firefighter during 2020 was for isolation, quarantine, or symptoms of suspected COVID-19. Despite the thousands of personnel at the incident base camps, there were no large-scale outbreaks of COVID-19 during the fire season at the fire incident base camps. This may be due to the outdoor setting of the incident base camp. Public safety responders in the United States do not have high vaccination rates; in fact, they are often lower than the general public, so rapid testing remains available in the base camps with concerns of outbreaks during the current season.

Supply logistics

The logistical medical supply chain was a challenge due to the remote location of many fire camps and support required for multiple simultaneous medical sites and other COVID-19 surge activity throughout California. EMSA distributes supplies from a centrally located warehouse near Sacramento and daily supply runs were not feasible. Resupply delays were exacerbated by miscalculations of utilization rate and ordering errors from both the field and warehouse. Furthermore, vendors could not supply the highest use items such as poison oak preventive solutions and lotions, medication for itching, and steroids (both topical and oral) for management of the rash. Staff mitigated some of these supply issues by acquiring the required items at local pharmacies.

Logistics has been addressed through the development of a digital inventory system incorporating bar codes that can track usage rates and anticipate supply needs. The warehouse inventory will be expanded, increasing par levels of commonly used supplies. The goal is to track inventory in the field and the warehouse and resupply field camps once or twice weekly rather than daily. The current inventory and formulary for these clinics are available in the online Appendix.

Training

Temporary volunteer providers come with a variety of experience and medical backgrounds. The ideal medical specialties for this work are urgent care or emergency medicine, internal medicine, and family medicine, although other specialties have been successful team members.

The surge of CAL-MAT deployments to support the COVID-19 response, in addition to fire camps, led to member deployment without the required training in ICS; orientation to equipment and logistics, team organization and roles, policy and procedures; and management of common medical issues. During the 2020 season, a manual was developed that provided treatment recommendations for common medical problems, including poison oak, as well as policies and procedures. Recommended best practices and treatment regimens were discussed among weekly provider conference calls and distributed in a written format. CAL-MAT will redesign training to include some just-in-time topics, but most modules will be completed on a 2-year cycle.

Staffing and leadership

During the 2020–2021 COVID-19 response, CAL-MAT was tasked with numerous new missions to support a medical surge. Maintaining staffing for multiple fire camps was a challenge, since at the same time CAL-MAT was staffing alternative care sites for COVID-19, shelter medical clinics, skilled nursing facility strike teams, and mobile COVID-19 testing teams. Registered deployed personnel increased 10-fold from 200 to more than 2000, and still needed substantial augmentation by contract personnel, other agencies such as California National Guard, and a second disaster registry (Health Corps). During the initial COVID-19 waves in 2020, many health care personnel were underemployed so increased staffing needs could be met; however, during 2021, CAL-MAT staffing was even more challenging since health care staff were in high demand and could receive much higher reimbursement from contract and travel nurse agencies. With the pool of experienced volunteers depleted, personnel were deployed who did not have field experience with CAL-MAT teams. Morale is critical in a small team living and working together and often depends on the skill of the team leader. Leadership is not an inherent quality and personnel problems occurred, as in any occupational setting. Temperament is also very important since this work requires resilience, flexibility, and tolerance for work in non-traditional health care settings like the austere environment of a fire incident base camp. Although medical providers commonly answer to non-medical administrators in health care settings, it can be problematic if the administrator has little or no medical training, supervisory, or leadership experience. For larger operations, a unified command between the Chief Medical Officer and the administrative mission support team commander has been most effective. The best solution is an adequate pool of known, experienced personnel.

Team function was further affected by extended duration missions, where personnel were replaced at irregular intervals. Training, staffing, and leadership have a direct impact on team performance, a critical issue for disaster response teams and emergency medical teams. Team cohesion and optimal function have been demonstrated to reduce medical errors. Reference Morey, Simon and Jay27,Reference Risser, Rice and Salisbury28

Behavioral health support

The most widespread and enduring medical impact following a disaster is behavioral health, which is often not addressed due to lack of understanding of the long-term impacts and lack of sufficient resources at the local level. Psychological stress and posttraumatic stress result from fear, anxiety over loss of housing and services, and exposure to devastation and injuries of loved ones and community members. Reference Kaul29 It is estimated that the majority of affected persons in a disaster area will have transitory distress symptoms and 30–40% will develop a new incidence disorder such as posttraumatic stress disorder or depression. This includes 10–20% of responders. These disorders can be prevented in many people if addressed within the first month. Reference Abeldaño and Fernández30–Reference Shultz and Forbes32 When available, disaster behavior health professionals provided on-site and virtual consultations for CAL-MAT members during deployments. California has developed response guides for local health departments that describe the resources and options for response. 33,34 CAL-MAT now provides on-site and virtual psychological consultations for team members during and following deployments.

Recovery

Medical and health functions continue during recovery. Fire debris and ash from destroyed structures are considered toxic waste that must be specially removed and disposed. After the Camp Fire, nearly 3.7 million tons of ash, metal, concrete, and contaminated soil were removed from 11 000 properties in Butte County. 35

Only then can decisions be made concerning repopulation and rebuilding. A special legislative exemption was provided to provide medical care for workers and residents in Paradise, California, working to clean up and rebuild after the Camp Fire [CA Health and Safety Code, § 1251.6 (2019)].

Conclusion

A critical component of the response to wildfires is medical support for health care facilities, displaced populations, and firefighters. California Health and Medical ESF-8 supports local jurisdictions for these needs and has a unique partnership with CAL FIRE to provider support in the incident base camps for large wildfires. As large and sustained wildfires become a regular occurrence across the western United States and in other countries, the California experience may inform planning and response for other response agencies. The empirical information from California is supported by expanding research as well as interest from disaster response agencies on the health and medical impacts of wildfires. 36–Reference Xu, Yu and Abramson44

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.347