Introduction

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can be developed after direct exposure to, or witnessing a traumatic, life-threatening event. PTSD is a condition characterized by prolonged anguish after a traumatic event involving actual or threatened death, injury, or sexual violence. It is a potentially chronic impairing disorder that is characterized by re-experiencing traumatic events and avoidance symptoms, as well as negative alternations in cognition and arousal. People with high levels of PTSD symptoms are bothered by intense, disturbing thoughts and feelings related to their adverse experiences which last long after the traumatic event has ended. They may relive the event through flashbacks or nightmares; they may feel depressed, fearful, or angry; and they may feel detached or estranged from other people. Individuals with PTSD may avoid situations, places, or persons that remind them of the traumatic event, and may have strong negative reactions to something as ordinary as a loud noise or an accidental touch. Reference Bryant1–Reference White, Pearce, Morrison, Dunstan, Bisson and Fone3

It is important to realize from the outset that the reactions of most people are not necessarily pathological responses that may serve as precursors of the subsequent disorder. Instead, many people will suffer from transient stress reactions in the aftermath of mass violence. These transient responses may occur a long time after the potentially traumatic event. Reference Schein, Houle and Urganus4 However, it should be emphasized that post-traumatic transient stress is a prevalent phenomenon and those suffering from it may experience several post-traumatic symptoms whose number and extremity do not amount, in most cases, to a level of PTSD diagnosis. Most people exposed to horrific war trauma are not incapacitated by the experience. Reference North, Abbacchi and Cloninger5 Only a minority of those who experience any traumatic event may respond with a higher level of distress and their post-traumatic symptoms level may reach that of PTS. Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein6,Reference Galea, Vlahov and Resnick7 There is a controversy concerning the pervasiveness of PTSD diagnosis among civilians who were affected by war. A study claimed that its prevalence is 12.9%. Reference Charlson, Flaxman, Ferrari, Vos, Steel and Whiteford8 Others have found that this prevalence amounts to 26% of civilians. Reference Morina, Stam, Pollet and Priebe9,Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and Van Ommeren10 In any case, more than 50% of the population who had faced the worst trauma in war situations retain their resilience and do not develop a high level of PTSD. Reference Murthy and Lakshminarayana11

A major question that has been hardly studied is what makes most civilians who have suffered war traumas, relatively resilient to PTSD. The present study presents a new perspective on this topic. The research on PTSD emphasizes the role of the traumatic event in determining the gravity of the ensuing pathology. Traumatic events such as family and social violence, rapes and assaults, disasters, and wars, as well as accidents and predatory violence confront people with a level of anxiety that may alter, in several cases, their capacity to cope and their threat perception, as well as their concepts of themselves, which may result in PTSD. Reference van der Kolk12

Gil et al. Reference Gil, Weinberg, Or-Chen and Harel13 emphasized, similarly, that developing PTSD is associated with higher levels of objective and subjective threats.

The study claimed that avoiding PTSD following traumatic war-related experiences (and distress-linked pathologies in general) will be determined by at least 4 factors: the impact of the traumatic event, the strength of personality characteristics that undermine coping and adjustment, the strength of coping supporting personality attributes, as well as pathology supporting and suppressing socio-demographic variables. It was argued that the PTSD symptoms of individuals who have faced the threats of war will concurrently reflect: (1) the perceived impact of the traumatic events, (2) pathology sustaining and opposing socio-demographic variables, such as gender or age, and (3) the balance of coping supporting personality attributes (e.g., individual resilience), when compared to coping suppressing characteristics (such as a lingering sense of danger). A lower level of post-traumatic symptoms will be associated with negative war experiences as less traumatic, with more favorable socio-demographic circumstances, and with a higher balance of protective personality elements. These factors are not exclusive predictors of PTSD symptoms. It was submitted that the 4 factors that will affect PTSD symptoms will also predict one’s level of psychological distress symptoms.

Everyone is characterized by a higher or lower level of individual distress that has developed throughout their lives and is not necessarily associated with the traumas of their present war encounters. Reference Huang, Cai and Zhou14 Psychological distress is viewed as an emotional disturbance that may impact the social functioning and day-to-day living of individuals. Reference Wheaton15 It is defined clinically as a state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of anxiety (e.g., restlessness, feeling tense, etc.) and depression (e.g., lost interest, sadness, and hopelessness), which may be associated with somatic symptoms (e.g., insomnia, headaches, and lack of energy). Reference Drapeau, Marchand, Beaulieu-Prévost and L’Abate16,Reference Mirowsky and Ross17 Ridner, Reference Ridner18 disagrees with this definition, claiming that psychological distress is seldom defined as a distinct concept and is often embedded in the context of strain and stress. Her theory submits that the defining feature of psychological distress is the exposure to a stressful event that threatens physical or mental health, the inability to cope effectively with this stressor, and the emotional turmoil that results from this ineffective coping. Adverse childhood experiences have a tremendous impact on psychological distress and well-being over a person’s lifetime. Reference Hughes, Bellis and Hardcastle19 The prevalence of psychological distress roughly ranges between 5% and 27% in the general population. Reference Chittleborough, Winefield, Gill, Koster and Taylor20,Reference Kuriyama, Nakaya and hmori-Matsuda21

War traumas as risk factors for PTSD

Restoring social and behavioral functioning after disasters and situations of mass casualty has been extensively explored over the last few decades. A summary of this research points to 4 main conditions under which posttraumatic stress symptoms may reach the level of PTSD. Reference Hobfoll, Watson and Bell22 First, the direct and indirect physical, social, and psychological pressures exerted by disasters may be devastating (e.g., the fear that an act of terror would encroach on one’s own life). Reference Reissman, Klomp, Kent and Pfefferbaum23 Second, adversities may decrease individuals’ ability to cope with further traumas and recover from their consequences. Reference Hobfoll24 Third, territory grants people a feeling of a secure base. Losing this sense of safety leads to high levels of dismay. Furthermore, ‘in many instances of disaster and mass casualty, the ongoing violence and aftershocks, massive failure to provide aid, and the secondary losses that follow the initial phase mean that there may be no demarcated period that can be termed post-trauma.’ Reference Hobfoll, Watson and Bell22 Fourth, traumatic events often shatter people’s sense of meaning and their assumptions concerning the existence of a just and orderly world. In these cases, post-traumatic stress may sometimes lead to PTSD.

Personality attributes and PTSD

Personality attributes that promote coping as compared to those that increase the impact of traumatic events may substantially affect the development of PTSD. Swickert et al., Reference Swickert, Rosentreter, Hittner and Extraversion25 support this contention by claiming that individual traits affect the development of PTSD by shaping cognitive processes, coping strategies, and interaction with social support processes. Examination of the available research shows that the search for such personality traits is quite limited and refers mainly to individuals who are already diagnosed as suffering from PTSD. Reference Husky, Pietrzak, Marx and Mazure26,Reference Smith, Dalgleish and Meiser-Stedman27 These individuals tend to score high on neuroticism which is robustly related to many mental disorders. Reference Lahey28,Reference Li, Lv, Li, Luo, Sun and Xu29 Crestani et al. report further that PTSD is positively correlated with harm avoidance and self-transcendence, and negatively correlated with self-directedness. Reference Calegaro, Mosele and Negretto30 The association between PTSD and self-directedness is further supported by previous studies. Reference North, Abbacchi and Cloninger5,Reference Yoon, Jun, An, Kang and Jun31 Research also shows that the response to stressful conditions reflects the strength of the traumatic experience, as well as the balance of individual health and pathology factors. Increased balance of protective processes over risk factors is the basis for attaining adaptive development, and reducing the level of psychopathology. Reference Condly32,Reference Lalongo, Rogosch, Cicchetti and Icchetti33

Socio-demographic risk factors for PTSD

Hahn claims that in contrast to persistent notions of ‘the natural course of disease,’ it has long been recognized that health outcomes are affected by several other factors, Reference Hahn34 1 of which is social. The social determinants of health are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes; the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, and live, as well as age; and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. Meta-analyses of correlates of PTSD have consistently found that it is associated with socio-demographic indicators, that is, with a lower prevalence of social disadvantage. These include younger age at the time of trauma and being a female. Reference Brewin, Andrews and Valentine35,Reference Tolin and Foa36 Other studies show that beyond the direct impact of the violence and damage caused by war, the risk of PTSD and other stress-related pathologies, PTSD is associated with numerous pre-trauma variables including lower social status and intellect, female gender, educational status, and history of trauma exposure before the index event, negative emotional attention bias, as well as personal and family history of psychopathology. Reference Lancaster, Teeters, Gros and Back2,Reference Fel, Jurek and Lenart-Kłoś37

Distress symptoms

Distress symptoms are the most common negative human reactions in response to threats and/ or disasters. Among the common reactions are symptoms of anxiety and depression. Reference Cénat, Blais-Rochette and Kokou-Kpolou38 Several researchers use the individual level of distress symptoms as a measure of resilience and/ or coping level. Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein6 An Israeli study has found that a higher emotional burden is associated with being female, younger, unemployed, and living in high socioeconomic status localities, as well as having prior medical conditions, and experiencing physiological symptoms. Reference Benjamin, Kuperman and Eren39

Correlates of post-traumatic stress symptoms and level of distress

Level of exposure to war

The perceived exposure to the perils of war refers to the extent to which people feel that the war threatens them personally, their dear ones, and their sense of safety in their living place. It is expected that more traumatic war experiences will increase the level of PTSD and psychological distress symptoms. Studies have shown that the intensity and frequency of exposure to war are often proportional to the severity of PTSD. Reference Fear, Jones and Murphy40,Reference Xue, Ge and Tang41 Furthermore, it has been found that the impact of exposure to war on the mental health of the civilian population is highly significant. Studies of the general population show a definite increase in the incidence and prevalence of mental disorders during times of war. Reference Murthy and Lakshminarayana11

Socio-demographic factors

Previous research has found, as indicated above, that the following demographic characteristics are more likely to be positively associated with a higher level of PTSD symptoms in the context of war: lower socioeconomic status, lower social and emotional support, being a female and having children, and perhaps also being highly devoted/ religious. Reference Fel, Jurek and Lenart-Kłoś37,Reference Businelle, Mills, Chartier, Kendzor, Reingle and Shuval42

Individual resilience

Bonanno et al,. Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini43 regarded individual resilience as a stable trajectory of healthy functioning after a highly adverse event, whereas Masten, Reference Masten44 defined it as ‘the potential of the manifested capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten the function, survival, or development of the system’ (P. 187). Resilience has been found to negatively correlate with PTSD in the aftermath of trauma. Reference Dhungana, Koirala, Ojha, Bahadur and Thapa45,Reference Wrenn, Wing and Moore46

Hope

Hope is described by Snyder, Reference Hope47 as a form of goal-oriented self-confidence and a sense of personal mastery in the service of goal pursuit, planning, and problem-solving, all of which play a major role in coping with adversities. Research shows that hope is inversely related to PTSD. Reference Joubert, Guse and Maree48,Reference Koenig, Youssef and Smothers49

Well-being

This has been defined as the combination of feeling good and functioning well; the experience of positive emotions such as happiness and contentment as well as the development of one’s potential, having some control over one’s life, having a sense of purpose, and experiencing positive relationships. Reference Huppert50 Well-being has been negatively correlated with PTSD. Reference Ouimette, Goodwin, Pamela and Brown51

Sense of danger

Threats and disasters often evoke the individual’s feelings that his/her life and/or family members’ life are in danger. Reference Eshel and Kimhi52 A high perceived life threat was associated with PTSD among those present at the site of the 2011 Oslo bomb explosion. Reference Heir, Blix and Knatten53

Hypotheses

Based on the above, the current study examines 6 predictors of PTSD psychological distress symptoms: subjective well-being, individual resilience, sense of danger, and level of exposure to war experience, as well as gender, and age. It is assumed that each of them will significantly predict PTSD and distress levels. The following hypotheses were examined:

-

1) A higher level of PTSD symptoms will be (a) positively predicted by the level of exposure to war threats; (b) positively predicted by a sense of danger; (c) negatively predicted by individual resilience and sense of well-being; and (d) will characterize more strongly, females and younger adults.

-

2) A higher level of psychological distress which is not necessarily related to living through war will be predicted in the same direction by stressful conditions, positive and negative personality characteristics, and socio-demographic variables.

Methods

Sample and sampling

The data was collected from July 22 to 28, 2022, about 5 months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, by Info-Sapiens.Footnote 1 The company owns a database of over 32000 residents of varied demographic regions of Ukraine (except for Crimea, NGCA of Donetsk, and Lugansk). The research questionnaire was translated into both Ukrainian and Russian languages and each respondent could choose the language he/ she preferred. The research questionnaire was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tel Aviv University and the respondents signed informed consent forms before they participated in this study. The present 1001 respondents represent a wide range of socio-demographic characteristics and geographic regions of Ukraine (See Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the investigated sample

Measures

PTSD level was determined by Lang and Stein’s 6-item Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-6). Reference Lang and Stein54 A score of 14 or more constitutes a cutting point that indicates difficulties with post-traumatic stress and possible referral for treatment. Reference Lang and Stein54,Reference Meredith, Eisenman and Han55 These 6 items represent 3 different facets of PTSD. The respondent is asked to indicate the extent to which he/ she has been bothered by each of these issues in the past month (For example: ‘repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience from the past’). The response scale ranges from 1 = Not at all, to 5 = Extremely. The validity of the PCL-6 was established by Lang et al. Reference Lang, Wilkins and Roy-Byrne56 , and its reliability in the present study is very high: (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Exposure to war

A 6-item scale based on a scale devised by Eshel et al., Reference Eshel and Kimhi52 determined the respondent’s level of exposure to the threats of war. (Example: ‘Did you find yourself in a situation where your life was in danger?’). The 5-point response scale ranges from 1 = Not at all, to 5 = To a very large extent. The reliability of this scale in the present study was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

Sense of danger

A short version of Solomon and Prager’s Sense of Danger scale was employed. Reference Solomon and Prager57 This 4-item version has been utilized due to its good reliability and validity which have been found in a previous study. Reference Kimhi, Eshel, Marciano and Adini58 Questions asked ranged from: ‘To what extent do you feel your life is in danger due to the war in Ukraine?,’ to ‘To what extent do you feel that the lives of your family members or those who are dear to you are in danger due to the war in Ukraine?’ The 5-point response scale ranges from 1 = not at all, to 5 = to a very large extent. Good reliability was found for this scale in the present study (Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

Individual resilience

Individual resilience has been measured by a short form of 2 items of the Connor–Davidson scale, Reference Campbell-Sills and Stein59 portraying individual feelings of ability and power in the face of difficulties (for example, ‘I manage to adapt to changes’). Vaishnavi et al. Reference Vaishnavi, Connor and Davidson60 have established the validity of such a short form of 2 items. The 5-point Likert response scale ranges from 1 = not true at all, to 5 = generally true. The internal reliability of this version in the present study is acceptable (α = 0.67).

Well-being

The short form of the Kimhi and Eshel well-being scale employed in the current study consists of 5 items concerning individuals’ perception of their present lives in various contexts, such as work, family life, health, or free time. Reference Kimhi and Eshel61 Responses to these items ranged from 1 = very bad, to 6 = very good. This scale has been validated in previous studies. Reference Kimhi, Eshel, Marciano and Adini58 Its Cronbach’s alpha reliability in the present study was found to be good (α = 0.78).

Hope

The present scale is based on the Jarymowicz and Bar-Tal, Reference Jarymowicz and Bar-Tal62 and Halperin et al., Reference Halperin, Bar-Tal, Nets-Zehngut and Drori63 hope scale. The current short version of this scale includes three items. A recent study demonstrated that the short versions of the four-item hope scale function equally well as their longer counterparts. Reference Pleeging64 The response scale ranged from 1 = very little hope to 5 = high hope. The reliability of the present version is good (α = 0.80).

Distress symptoms

A short version of the BSI scale was incorporated. Reference Derogatis, Savitz and Mahvvah65 The present study included 4 items of the anxiety sub-scale (for example: ‘I feel such restlessness that it is impossible to sit in 1 place’) and 4 items of the depression sub-scale (Example: ‘I feel hopelessness about the future.’ A similar short form of this scale was successfully employed in a recent study of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reference Eshel, Kimhi, Marciano and Adini66 Respondents were asked to report the extent to which they are currently suffering from any of the problems presented. The 5-point response scale ranged from 1 = not at all, to 5 = to a very large extent. The internal reliability of the distress scale in the present study was high (α = 0.89).

Demographic characteristics

The family income level was established by the following item: ‘The average income of a Ukraine family today is 14.756 RPH per month. Your family’s income is 1, much lower than this average; 2, lower than this average; 3, around this average; 4, higher than this average; and 5, much higher than this average. Respondents also indicated their age (in years), gender, having children, and education level, as well as religion, political inclination, the size of their community, and whether or not they are displaced.

Results

As a first step, the study examined the levels of PTSD and distress symptoms in our sample. The results indicated that only 10% reported a high level, 66% reported a medium level and 24% reported a low level of PTSD; 11% reported a high level, 71% reported a medium level, and 18% reported a low level of distress symptoms. These findings indicate that most of the participants in this study do not suffer from either PTSD or extreme levels of distress. Next, the correlations were examined between the investigated variables. Results showed, as expected, that PTSD symptoms and distress levels were negatively associated with the level of exposure to war and a sense of danger, and positively correlated with individual resilience, well-being, and hope (See Table 2). Results also showed that both PTSD and distress symptoms significantly correlated with average family income; the lower the income, the higher the PTSD and distress symptoms. Age was significantly correlated with PTSD (but not with distress symptoms): the younger the age, the more PTSD symptoms were reported.

Table 2. Correlations between the investigated variables

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

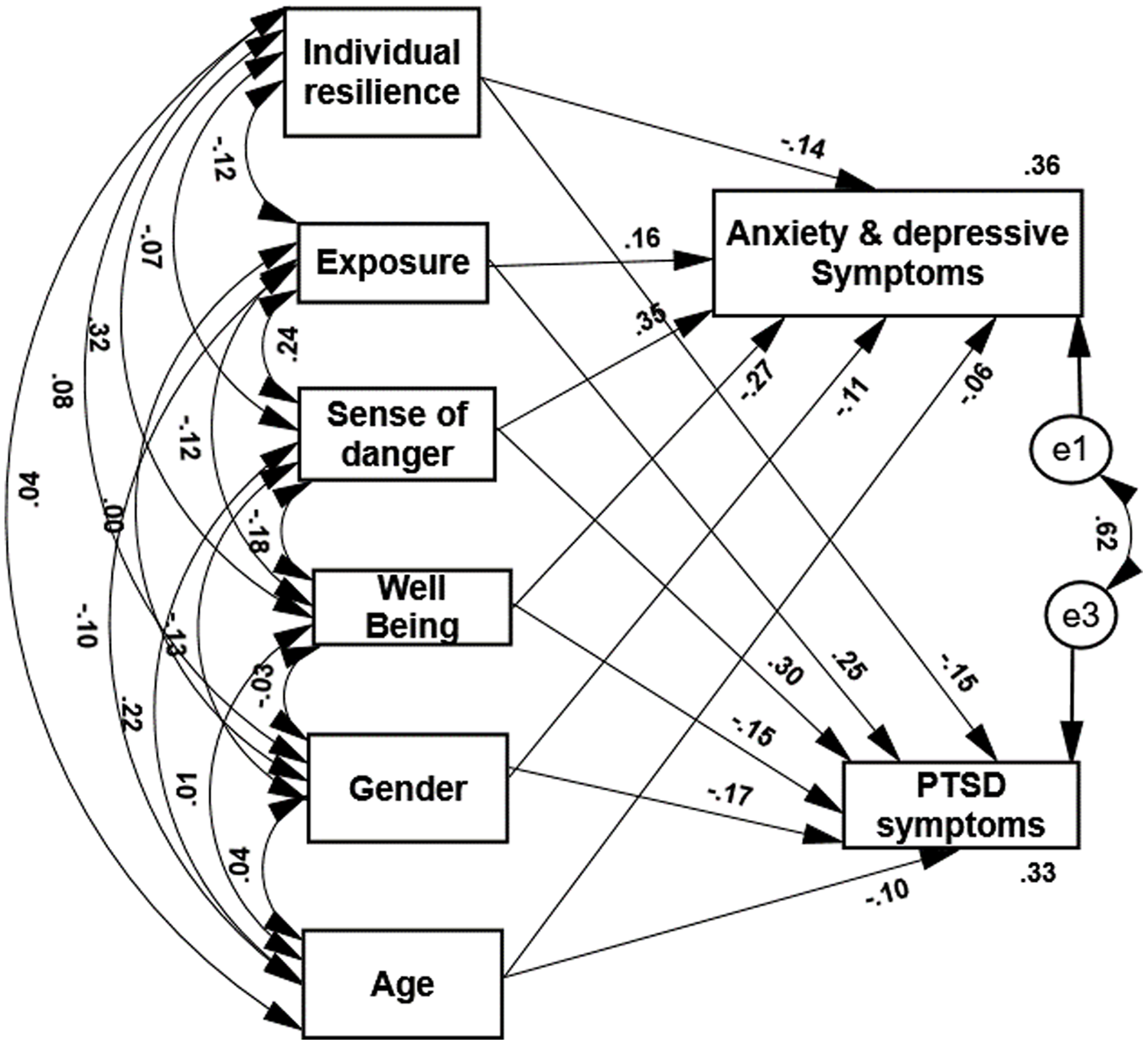

Lastly, path analysis was used to explore our 2 hypotheses concerning the predictability of both psychological distress and PTSD symptoms by the investigated variables. Figure 1 presents these predictions and indicates that as hypothesized, both PTSD and distress levels are positively predicted by the exposure to the stress of war and by the coping-suppressing attribute of sense of danger, negatively predicted by the coping-supporting personality traits of individual resilience and well-being, with higher values among women and young people. All the examined paths are significant at a P < 0.001 level, except for the path from age to level of distress (P < 0.05). The strongest predictor of both distress and PTSD symptoms was the sense of danger. Feeling threatened by actual or potential risks increases the likelihood of having higher post-traumatic stress symptoms and a higher level of distress symptoms. The second-best predictor indicates a major difference between coping with war-related and other sources of stress. Exposure to war strongly predicts the PTSD symptoms level, whereas the general level of distress symptoms, which are not necessarily connected to the war, is strongly affected by a lower sense of well-being. The 6 predictors explain 36% of the stress symptoms and 33% of the PTSD symptoms variability.

Figure 1. The impacts of psychological and demographic determinants on PTSD and distress symptoms. *All paths are significant.

Discussion

The present study examines factors that help most civilians, who face the threats of war, to develop a resistance to the effects of this stress, refrain from developing extreme levels of distress and avoid passing from the post-traumatic stress level to the level of PTSD symptoms that calls for therapeutic help. The research on coping with stress posits that the ability to re-adjust - ‘bounce back’ - after a stressful encounter and return to pre-traumatic functioning, depends on the dynamic transactions between risk and protective factors, which play a central role in building informed models of resilience to stress. An increased balance of protective determinants over risk factors is suggested as the basis for attaining adaptive development, and reducing the level of psychopathology. Reference Condly32,Reference Lalongo, Rogosch, Cicchetti and Icchetti33 The evidence that most people reveal resilience in response to potentially traumatic events and do not develop PTSD, suggests that there are key individual factors that underlie the relation between response to negative effect and psychopathology. Reference Shoshani and Slone67 It is claimed, accordingly, that the balance of at least 4 components helps people cope with the stress and adversity of war and with their distress level: the level of traumatic events encountered by them, the strength of existing pathological factors such as a sense of danger, the impact of coping-supporting personality attributes like well-being and resilience, and coping-backing or opposing socio-demographic variables such as gender and age.

Clinical studies claim that traumatized individuals frequently develop PTSD. Reference van der Kolk12 It should be noted that what may be true for individuals whose reactions to traumatic events were extremely high, reached the PTSD level, and found their way to get help from professional clinical personnel, is not necessarily true for the general population, who may cope with the traumatic events in a much more resilient manner. War-related strains and traumas may shake this balance, increasing the relative weight of its pathological elements. However, there is a growing awareness that traumatic events do not always have adverse psychological outcomes. Reference Halligan and Yehuda68 Furthermore, systematic research indicates that many people who live in chronic war zones retain their resilience and emerge less damaged than traditional theories might expect. Reference Bonnano69 From a socio-ecological perspective, resilience may be perceived as the capacity of an individual to develop or access psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources necessary for psychological health. Reference Ungar70 Most civilians in war zones exhibit post-traumatic adaptation and prevail in the aftermath of traumatic war experiences. Reference Morina, Stam, Pollet and Priebe9 A score of 14 or more on the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-6) constitutes a cutting point that indicates PTSD. Reference Lang and Stein54,Reference Meredith, Eisenman and Han55 Our data show, accordingly, that 67% of the investigated respondents, who are currently experiencing the war in Ukraine, have not reached this cutting point of PTSD.

Our results also show that exposure to war had the greatest impact on both PTSD and the distress symptoms that did not necessarily result from experiencing war. However, these results indicate as well that traumatic war-related events did not manage to disturb the individual resilience of majority of the respondents and increase the post-traumatic stress to a level of PTSD. This resilience balance enabled most people to withstand the stress of war, to re-adjust psychologically, and return eventually to the pre-war level of functioning. The path analysis conducted in this study indicates that all the investigated psychological and demographic predictors significantly and consistently predicted both PTSD and distress symptoms. As expected, both these factors are negatively predicted by the coping-supporting variables of individual resilience and well-being; both of them are positively predicted by the coping-suppressing variables of exposure to war and sense of danger, and both of them are more prevalent among younger people, and females. A further examination of these predictions shows that both PTSD scores and distress levels are most strongly predicted by the sense of danger. However, the more general nature of the level of distress that is not necessarily related to the war is expressed by the findings that its second-best predictor, well-being, represents a general coping supporting approach, whereas the second-best predictor of the PTSD symptoms (level of exposure to the perils of war) is associated directly to the ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict.

Limitations

This study points successfully at 4 factors whose balance helps most of the general population to be resilient to post-war PTSD. However, several limitations should be mentioned: first, further research should examine additional risk factors and protective factors that may contribute to this balance in additional contexts. Second, since the sample was determined by an internet company, it does not correctly represent the whole Ukraine population: The average education level of the respondents is higher than the Ukraine national average, the majority of the respondents reside in large cities while the residents of the small towns and villages are under-represented, and the sampling was limited to those who use the Internet. Third, the sample did not include respondents over the age of 55 or the regions that were occupied by Russia.

Conclusions

People experience different traumas throughout their lives and develop a characteristic level of individual anxiety as well as resilience-supporting personality attributes. Concurrently they internalize their stress enhancing and stress suppressing socio-demographic characteristics. The balance of these factors enables each of them to develop a sense of resilience and allows them to face successfully, further stressful and traumatic events. This sense of resilience supports most of them in preventing the conversion of their post-traumatic stress symptoms into PTSD when they have to live through war. It is recommended that the study be repeated as longitudinal research throughout the war, to identify the persistence of the protective measures over time.

Author contributions

SK and BA conceptualized the study and collected the data; YE and SK analyzed the data; YE drafted the first version of the manuscript; HM reviewed and edited the manuscript; all authors read the revised the manuscript and approved the final version.