Emergency medical services (EMS) providers give medical and trauma care to patients. They are the first line of care for those with urgent needs and often stabilize patients for transport to definitive care facilities. During disasters and public health emergencies, they also fill an integral role by supporting health care, public health, and public safety.Reference Maguire, Dean and Bissell1 In such situations, those first responders are at significant risk of injury and death. For instance, during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto, Canada, in 2003, of the 850 paramedics who responded, more than half were exposed to SARS and placed in quarantine, some of them developed SARS-like symptoms, and 4 of them were hospitalized.Reference Maguire, Dean and Bissell1,Reference Silverman, Simor and Loutfy2 This incident resulted in a dramatic decrease in their workforces, which negatively affected the health-care system in the area by reducing its surge capacity. Moreover, the recent Ebola outbreak in 2014 has shown high infection and death rates among health-care professionals. A report from the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that health-care workers are 21 to 32 times more likely to be infected with Ebola compared with the general population.3 These disease outbreaks resurfaced the concern of willingness of health-care professionals to work during such pandemics.

Generally, EMS providers, as a part of the health-care system, are willing to prioritize the needs of their patients over their personal needs and safety, especially during disasters.Reference Chaffee4 While EMS providers have ethical and professional duties to work, these duties have limits when doing so could put them or their family members in serious dangers.Reference Singer, Benatar and Bernstein5 Research studies demonstrate different findings regarding the attitude of health-care workers to work during different types of disasters, including disease outbreaks.Reference Damery, Draper and Wilson6-Reference Trainor and Barsky12 Studies found that man-made events and pandemics are typically the disasters to which first responders feel unfamiliar and fear, and in turn, are less willing to respond.Reference Connor13-Reference Smith, Morgans and Qureshi15

During disasters, sufficient staffing is essential to keep the health-care system functional. EMS is an invaluable asset and considered the portal to the larger health-care system.Reference Maguire, Dean and Bissell1 In addition to their traditional work, during disease outbreaks, EMS providers can also help in other roles, such as distributing and administering vaccines and medications, as well as providing community education.Reference Maguire, Dean and Bissell1 While EMS personnel are among the frontline health-care providers during disasters, there is very little research on their attitude during disasters and public health emergencies.Reference Watt, Tippett and Raven16 To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, there is a lack of such research in Jordan and the Middle East. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the perception and attitude of EMS providers in Jordan to work during disease outbreaks, as well as the factors that may influence their decision.

METHODS

Design/The Survey

An expert panel developed a survey questionnaire specifically for EMS providers in Jordan. The paper-based survey was developed in English then translated into the Arabic language to make it more understandable by potential participants. The survey included 37 items addressing the following domains: (1) demographics (8 items); (2) attitude toward working during disease outbreaks (1 item); (3) concerns for working during disease outbreaks (7 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.834; low and high concern); (4) employer and the workplace (12 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.826; agree and disagree); (5) work obligation (8 items; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.890; obligated and not obligated); and (6) role of family (2 items). Factor analyses and internal reliability analyses were performed whenever appropriate to reduce variables and validate categories.Reference Pallant17

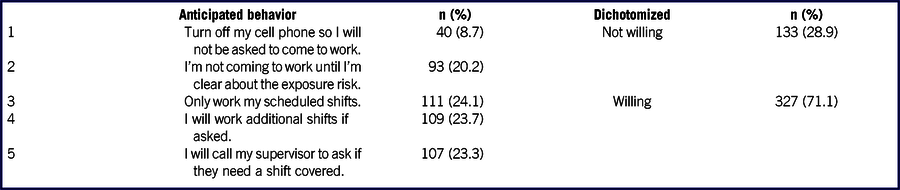

To examine the attitude, a disease outbreak scenario was developed. The scenario is about a disease outbreak unfolding in a country outside Jordan with very limited information about its characteristics. Early reports show that it is an airborne disease with flu-like symptoms and high mortality rates. Some cases of the disease were reported in Jordan, and eventually in the workplace. Participants were then asked about their response to such a situation. They were asked to choose the most appropriate choice from the given five alternatives. These alternatives were: (1) turn off my cell phone so I will not be asked to come to work; (2) I’m not coming to work until I’m clear about the exposure risk; (3) only work my scheduled shifts; (4) I will work additional shifts if asked; (5) I will call my supervisor to ask if they need a shift covered.

The third to sixth domains are 6-point Likert-type questions. The questions outlined a series of statements related to work during disease outbreaks. Participants were asked to choose from 1 to 6 with 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 6 represents “strongly agree.” Other choices for the domains include “not at all concerned” and “extremely concerned”; “not at all confident” and “extremely confident”, and “not at all obligated” and “extremely obligated”.

Setting

EMS system in Jordan is exclusively provided by the Jordanian Civil Defense (JCD), a quasi-military system. EMS in Jordan comprises of approximately 2000 providers that encompass emergency medical technicians (EMTs), intermediate, and paramedics who provide all types of prehospital care.

Participants

The questionnaire was pilot tested on 10 participants, and was then modified according to the feedback provided. The expert panel approved the final form of the survey. Over the months of October and November 2018, a total of 500 surveys were distributed randomly to frontline EMS providers in the JCD. The surveys were handed to the EMS director who distributed them evenly to the EMS departments and stations across the country. Each department was informed by the EMS director to give the chance to all ambulance workers to voluntarily participate in the study. The number of questionnaires was stratified according to the number of EMS workers in the regions (north, middle, and south) to give equal chance for all potential participants. Completed surveys were returned in sealed envelopes to Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST) for further data entry and analyses.

Data Analysis

To begin analysis, all continuous variables were summarized as means and standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Participant’s responses were dichotomized where possible to indicate positive or negative attitude. For instance, in the 6-point Likert-type questions, the first 3 choices were merged and considered “disagree,” a negative attitude; and the last 3 choices were merged and considered “agree,” a positive attitude. In addition, for the scenario question, choices were also dichotomized into “willing” and “unwilling” to allow for binary logistic regression.

Bivariate regression analyses were individually conducted to all independent variables to assess the impact of each variable on the likelihood to report for duty during a disease outbreak. Variables with a P value less than 0.1 were entered into the full model. Binary logistic regression was then conducted using a backward stepwise method to identify the predictors of willingness to report for duty, with a P-value of 0.05 to determine the statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22 (Chicago, IL).

Ethical Approval

JUST Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved the study procedure before starting data collection (IRB NO: 24/113/2018). The research team also contacted the JCD regarding the survey and obtained the approval.

RESULTS

Of 500 surveys distributed, 34 surveys had missing information and were excluded from the study, accounting for these exclusions the dataset included 466 (93.2%) completed surveys. All participants currently working in the JCD and completed the survey were included in the study. Table 1 describes the demographics of the study participants. The participants had a mean age of 27 (SD 4.3) years; the majority were males (70.2%). The majority were certified as paramedics (71.9%), with a mean work experience of 8 years (SD 4.1).

TABLE 1 Demographics of the Study Participants

Abbreviations: EMT, emergency medical technician; SD, standard deviation N = 466.

Participants’ Perception Toward Working in a Hypothetical Pandemic Scenario

Table 2 summarizes the participants’ responses to the hypothetical outbreak scenario. Responses demonstrated that “sticking with the scheduled shifts” is the option that participants chose the most (24.1%), and the option chosen the least was “turning off cell phone” (8.7%). Responses were dichotomized into “not willing” and “willing” with the majority of participants (71.1%) are willing to report for duty in the case of a disease outbreak (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Frequencies of Participants for Scenario Options

N = 460.

Factors Influencing Reporting to Work During Disease Outbreaks

Survey participants were asked about their concerns toward work during disease outbreaks such as the given scenario. More than two-thirds of participants (68.5%) expressed concern of “becoming infected and getting ill,” 67.3% were concerned about “dying from infection,” and, of interest, 79.0% were concerned about “infecting family members.” Three-quarters (75.2%) of participants were concerned from the “lack of appropriate information” about the outbreak, 70.4% concerned about the “shortage in personal protective equipment” (PPE), and 79.8% concerned from “lack of availability of vaccines or effective treatment.” Overall, 72.7% of participants expressed their concern about working during disease outbreaks.

Three-quarters (75.1%) of participants agree that “disease outbreaks put their families at risk of infection higher than the general population,” and 60.3% agree that their “concern for family has a major effect on their decision to come to work.” When it comes to “who comes first during disease outbreaks,” work obligation was indicated the highest (45.3%), followed by family safety (29.2%), and self-safety (25.5%).

Participants were also asked about their employer and the workplace. More than half of the study participants (56.3%) agree that their employer has “efficient systems in place to manage disease outbreaks,” 61.1% agree that their employer will provide “updated information” about the progress of the outbreak and “adequate” PPE, 63.4% agree that their employer will provide “treatment and vaccines” once available. Overall, more than two-thirds (68.5%) of participants were confident that their employer would perform their responsibilities to keep workers safe. With regard to disciplinary actions, 61.3% of participants agree that their employer will implement strict disciplinary actions against workers who did not come to work during disease outbreaks, and less than half (40.9%) agree that they are coming to work because of these disciplinary actions. Yet, less than half (42.6%) believe that those who did not show up to work should be punished.

When it comes to knowledge and training, more than two-thirds (68.1%) of participants agree that they have “adequate knowledge and training” for disease outbreaks, and 59% believe that “lack of knowledge and training could influence their decision to come to work.”

Predictors of Reporting for Duty During Disease Outbreaks

As shown in Table 3, demographic characteristics were examined for their influence on reporting for duty using bivariate regression analyses. Age (bivariate odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.94-1.03), gender (bivariate OR, 0.81; 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.25), marital status (bivariate OR, 0.96; 95% CI = 0.63 to 1.46), presence of children (bivariate OR, 1.26; 95% CI = 0.83 to 1.91), and years of experience (bivariate OR 0.98; 95% CI = 0.93 to 1.04) were not significant predictors of reporting for duty. While education (diploma) and job title (EMT-intermediate) show significance on the bivariate regression analyses (bivariate OR, 2.68; 95% CI = 1.15 to 6.19; bivariate OR, 2.35; 95% CI = 1.21 to 4.56, respectively), they did not show significance in the multivariate model.

TABLE 3 Predictors of Reporting for Duty

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EMS, emergency medical services; EMT, emergency medical technician; OR, odds ratio; PPE, personal protective equipment.

* Significant P value.

Yet, seven independent variables remained statistically significant in the multivariate logistic regression model. Respondents who are confident that employer will provide adequate PPE (OR, 3.95; 95% CI = 2.31-5.42), have adequate knowledge and training for disease outbreaks (OR, 3.04; 95% CI = 1.71-5.39), agree with the strict disciplinary actions to enforce reporting for duty (OR, 2.52; 95% CI = 1.33-4.78), or feel obligated to work even if some co-workers become infected with the disease (OR, 2.19; 95% CI = 1.15-4.18) were significantly more likely to report for duty during disease outbreaks. Conversely, those who feel obligated to work if they did not receive appropriate training (OR, 0.52; 95% CI = 0.27-0.99), agree with the family effect on their decision to come to work (OR, 0.40; 95% CI = 0.21-0.73), or concerned about shortage in PPE (OR, 0.40; 95% CI = 0.20-0.76) were significantly less likely to report for duty during disease outbreaks.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that in a scenario of a disease outbreak, more than two-thirds of the study participants would be willing to come to work. Previous research studies are diverse in their results. That is, in a systematic review, Connor (2014) found that health-care professionals are 25% to 82% willing to work during pandemics compared with 83% to 90% for natural disasters.Reference Connor13 In the EMS field, Tippett et al. (2010) found that 56.3% of the study sample are willing to work during outbreak conditions.Reference Tippett, Watt and Raven18 In another study, Barnett et al. (2010) showed more optimistic results as they found that 93% of EMS professionals would be willing to report to work if required, and 88% if asked, but not required.Reference Barnett, Levine and Thompson19 Of interest, Alwidyan (2016) found that, while the interviewed EMS participants were “thrilled” and “excited” to work during natural disasters, they expressed varying concerns about working in pandemic conditions.Reference Alwidyan20

Predictors of Reporting for Duty

The study participants were diverse in their age, gender, marital status, presence of children, education, job title, and experience. These differences were examined for their potential effect on the decision to reporting for duty. The study found that, except for education and job title, demographics were not predictors of reporting for duty during disease outbreaks. This contradicts with previous research studies indicating that male gender and prior experience are predictors of willingness to come to work, while age reported having contradictory findings.Reference Devnani7 Our study found, however, that those who have diploma degree or being EMT-intermediate were predictors on the bivariate analyses, but were not remained on the multivariate logistic model (Table 3).

Among the 23 independent variables included in the final model, 7 variables remained significant predictors on the multivariate logistic regression. Confidence that employer will provide adequate PPE, having adequate knowledge and training for disease outbreaks, agreement with strict disciplinary actions against providers who did not show up during disease outbreaks, and feeling obligated to work even if some coworkers become infected were predictors of reporting for work. On the other hand, not receiving appropriate training, concern for family, and concern about shortage in PPE were predicted barriers of reporting for work.

It is reported that confidence in the employer was a predictor of willingness to work during disasters.Reference Trainor and Barsky12 Given that disease outbreaks are associated with a high level of uncertainty in the early stages, employers need to communicate with front-line workers and keep them abreast of the evolving outbreak.Reference Ives, Greenfield and Parry21 Our study found that more than two-thirds of participants were confident that their employer would perform their responsibilities to keep workers safe. Additionally, the study found that the majority (61.1%) of participants were confident that their employer will provide adequate supplies of PPE. Those who were confident with their employer to provide PPE were 4 times more likely to report to work than those who lack confidence (Table 3). Conversely, the present study found that concerns for shortage in PPE found to be a major predicted barrier for reporting to work, which is congruent with the findings of previous research studies.Reference Barnett, Levine and Thompson19,Reference Mackler, Wilkerson and Cinti22

More than two-thirds of the study participants indicated that they have appropriate knowledge and training for disease outbreaks. Those who indicated that they have adequate knowledge and training are 3 times more likely to come to work during disease outbreaks as indicated by the logistic regression model (Table 3). Not receiving appropriate training, however, was found to be a predicted barrier for coming to work. These results are in congruence with a previous study on paramedics indicating that willingness to work increase significantly with adequate knowledge about the disease.Reference Tippett, Watt and Raven18 It is worth mentioning here that EMS providers are not trained to diagnose infections in the prehospital settings, rather they are trained to appropriately handle patients with potential infections.Reference Bissell, Seaman and Bass23 Nevertheless, a study by Shaban (2006) found that EMS personnel have poor knowledge of infectious diseases and principles of infection control.Reference Shaban24

Concerns for family have a major effect on reporting to work as indicated by the study findings. Participants indicated that they are concerned about infecting their family members (79.0%) more than their concern of becoming infected themselves (68.5%), which was also reported by previous research.Reference Dimaggio, Markenson and Loo8,Reference Connor13,Reference Alwidyan20,Reference Ives, Greenfield and Parry21 Our study also found that the majority of participants (60.3%) indicated that their family has a major effect on their decision to come to work, and this was the strongest predicted barrier on reporting to work as indicated by the logistic regression model (Table 3). These findings are in congruence with the previous studies. According to Trainor and Barsky (2011), the main source of role conflict during disasters is the uncertainty regarding the safety of family members and the feeling that first responders should protect their families.Reference Trainor and Barsky12 Other research studies show that family safety was number one concern for all health-care professionals during disease outbreaks.Reference Barnett, Levine and Thompson19,Reference Ives, Greenfield and Parry21,Reference Mackler, Wilkerson and Cinti22 For instance, although Mackler et al. (2007) found that 91% of the participants would remain on duty if they have been vaccinated, this percentage falls to 38% if their families have not received the vaccine.Reference Mackler, Wilkerson and Cinti22

This study provides one of the first empirical examinations of the potential behavior of EMS providers toward working during disease outbreaks in Jordan, and probably the Middle East. EMS employers need to know their potential workforce, the expected number of personnel who may, or may not, show up, and the factors that led to their absenteeism. Knowing the intended behavior of EMS providers enables decision-makers to plan for them and to implement measures that enhance willingness to report for duty. EMS needs to be efficient when it comes to plan for, respond to, and recover from health disasters.

Limitations

There are several limitations need to be discussed here. The study conducted on EMS providers of the Jordanian Civil Defense. While the sample size was more than 20% of the total EMS population and fairly representative in terms of demographics, we cannot exclude selection bias. That is, while the survey distribution was clustered according to Civil Defense departments and stations, there was no control over giving equal chance for all potential participants due to the quasi-military style of the Civil Defense in Jordan. Therefore, the findings of this study should be considered with caution. It is worth mentioning here that EMS in Jordan is much like the fire-based EMS, which is the most common in the United States and represents approximately 40% of all EMS agencies.25

The study looks for the potential attitude of people after receiving a hypothetical situation, an approach called perception studies.Reference Trainor and Barsky12 In real disease outbreaks; however, there will be many coincidental situations for each individual in the EMS system that the researcher cannot bring about in a simple case scenario. Therefore, this approach has difficulty in simulating the real-life situations of participants, which ultimately could affect the real beliefs and views of them. However, with little, if any, previous disease outbreak experience, it is challenging to anticipate with confidence the expected behavior of EMS participants, making perception studies the appropriate methodology to explore pandemic disasters.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found that even with the quasi-military style of EMS, approximately one-third of EMS providers may not show up if they believe that they or their family members become at risk of infection. The strict disciplinary actions by the authoritative EMS system was not a factor to enhance reporting for duty. Rather, confidence in employer of providing adequate supplies of PPE and vaccines as well as adequate knowledge and training for disease outbreak are the main predictors of willingness to come and work during pandemics. On the other hand, concerns for family safety and shortage in PPE found to be the major barriers for fulfilling their duties.

Continuing education courses about infectious diseases and infection control could be the starting point for improving the EMS workforces during pandemics. Equally important, the EMS employers need to provide appropriate supplies of PPE and the training on their use such as donning and doffing procedures. This would protect providers from the risk of infection, ameliorate their concerns of infection, and enhance their trust relationship with their employers.

Funding

This project was funded by Jordan University of Science and Technology (Research grant number: 20180092).