Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has emerged as a global pandemic with 162 million confirmed cases and 3.4 million deaths worldwide, as on 18 May 2021 [1]. As a part of control measures against COVID-19, vaccines have been launched in India from 16 January 2021, which has been subsequently scaled up in response to the surge of cases starting in April 2021 [2]. The second wave of pandemic in India has triggered a massive humanitarian crisis with unprecedented number of hospitalisations and deaths [Reference Mallapaty3]. Mass vaccination against COVID-19 has emerged as a key preventive strategy [Reference Kumar4].

In the first phase, health care workers including medical students were targeted for vaccination with either of the two vaccines approved for restricted emergency use – Covishield or Covaxin. Covishield is manufactured by Serum Institute of India under license from Astra Zeneca (adenovirus vectored ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine – AZD1222) [Reference Kumar4, Reference Padma5] whereas the inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine Covaxin (BBV152) is manufactured in India by Bharat Biotech in collaboration with Indian Council of Medical Research [Reference Padma5, 6]. From 1 March 2021, COVID-19 vaccination has been extended to those aged more than 60 years and those with comorbidities from 45 to 59 years of age [2]. Subsequently, starting 1 April 2021 and 1 May 2021, all individuals in India aged 45–59 years and 18–44 years have become eligible to receive vaccination, respectively. The process of registration for the vaccination is done online through the COVID-19 Vaccine Intelligence Network (CO-WIN) portal which is developed with the support of United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) [7]. It is also configured to track enlisted beneficiaries, issue short messaging service (SMS) reminders and vaccination certificates for users [7].

Vaccine hesitancy has been frequently studied among health care workers and especially medical students [Reference Paterson8]. The COVID-19 pandemic spurred the rapid development of vaccines with their prominent coverage in news and social media [Reference Kashte9]. Recent studies highlighted the concerns regarding adverse events, unduly rapid vaccine development and poor vaccine efficacy as some of the possible reasons for vaccine hesitancy among medical students [Reference Manning10–Reference Qiao13]. In the Indian scenario, out of the two vaccines, the safety and phase 3 efficacy data were publicly released for Covishield through a scientific publication of the parent Astra Zeneca vaccine [Reference Voysey14, Reference Bhuyan15]. For Covaxin, the safety and immunogenicity data of phase 1 trial is available [Reference Ella16]. An announcement of 81% efficacy has been made on 3 March 2021 [6], while its peer-reviewed scientific publication is awaited.

Although provided free of charge, there had been no option for the health workers to choose between the two vaccines, since allocation of vaccines to health facilities had been centrally determined owing to limited supply in the initial phase. High vaccination converge among medical students is needed not only because of their role as future physicians, but also because they are expected to provide COVID-19 care in high burden situations [Reference Wallen17]. Therefore, considering the recent surge in COVID-19 cases in India, the study of vaccine hesitancy among medical students is important. The present study aims to assess the awareness and sources of vaccine information, attitudes and possible determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students enrolled in MBBS course in India.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among the cohort of medical students in India for a period of around 5 weeks from 2 February–7 March 2021.

Sample size was calculated pertaining to the prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy or refusal among medical or nursing students from previous reports which ranged from 6% in Egypt, 13.9% in Italy and 23% in USA [Reference Lucia, Kelekar and Afonso12, Reference Saied18, Reference Barello19]. This yielded a sample size of 962 individuals corresponding to the lowest prevalence of 6% from Egypt, relative precision of 25% and alpha value of 5%.

An anonymous online structured questionnaire (Supplementary file 1) was prepared using evidence from prior studies on vaccine hesitancy in general [Reference Afonso20, Reference Kernéis21] and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students [Reference Lucia, Kelekar and Afonso12]. The questionnaire was prepared in English language which could be understood by medical students as it is the medium of instruction of medical course throughout India. It was designed to collect information regarding basic demographic details, awareness and sources of information regarding COVID-19 vaccine, attitudes regarding the vaccine and prior vaccination experience. This questionnaire was deployed online using Google forms. Its link was shared by the student investigator within the social media network of medical students – both individually and mainly through the WhatsApp groups, which included students of a particular batch studying in medical colleges. The students further circulated it among their acquaintances within the same medical college. Respondent-driven sampling strategy was used to target all medical students consenting and willing to spare the time to fill the survey. No financial or in-kind reward was offered to students who completed the survey.

Upon completion of the survey, data were downloaded in comma-separated values format and data analysis was conducted using SPSS software v23.0 and EpiInfo™ v7.2.4. Categorical variables related to the survey items were tabulated and odds ratio for vaccine hesitancy was calculated using univariate approach. Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression was conducted to test for plausible determinants of vaccine hesitancy while adjusting for gender, type of medical college, being in pre-clinical or clinical part of course and lack of prior vaccine experience. Similar analysis was repeated for exploring the determinants of hesitancy of joining COVID-19 vaccine trial. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was taken as significant.

The study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) – Jodhpur, India (Ref: AIIMS/IEC/2021/3438). Data collection was completely anonymous with no individual level identifying information such as name, email or mobile number of student or name of medical colleges being collected (Supplementary file 1).

Results

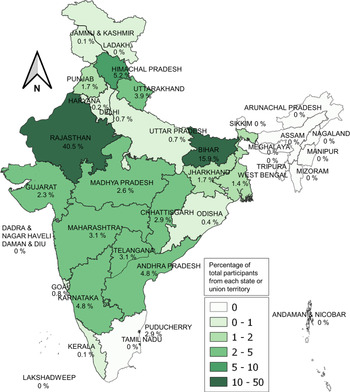

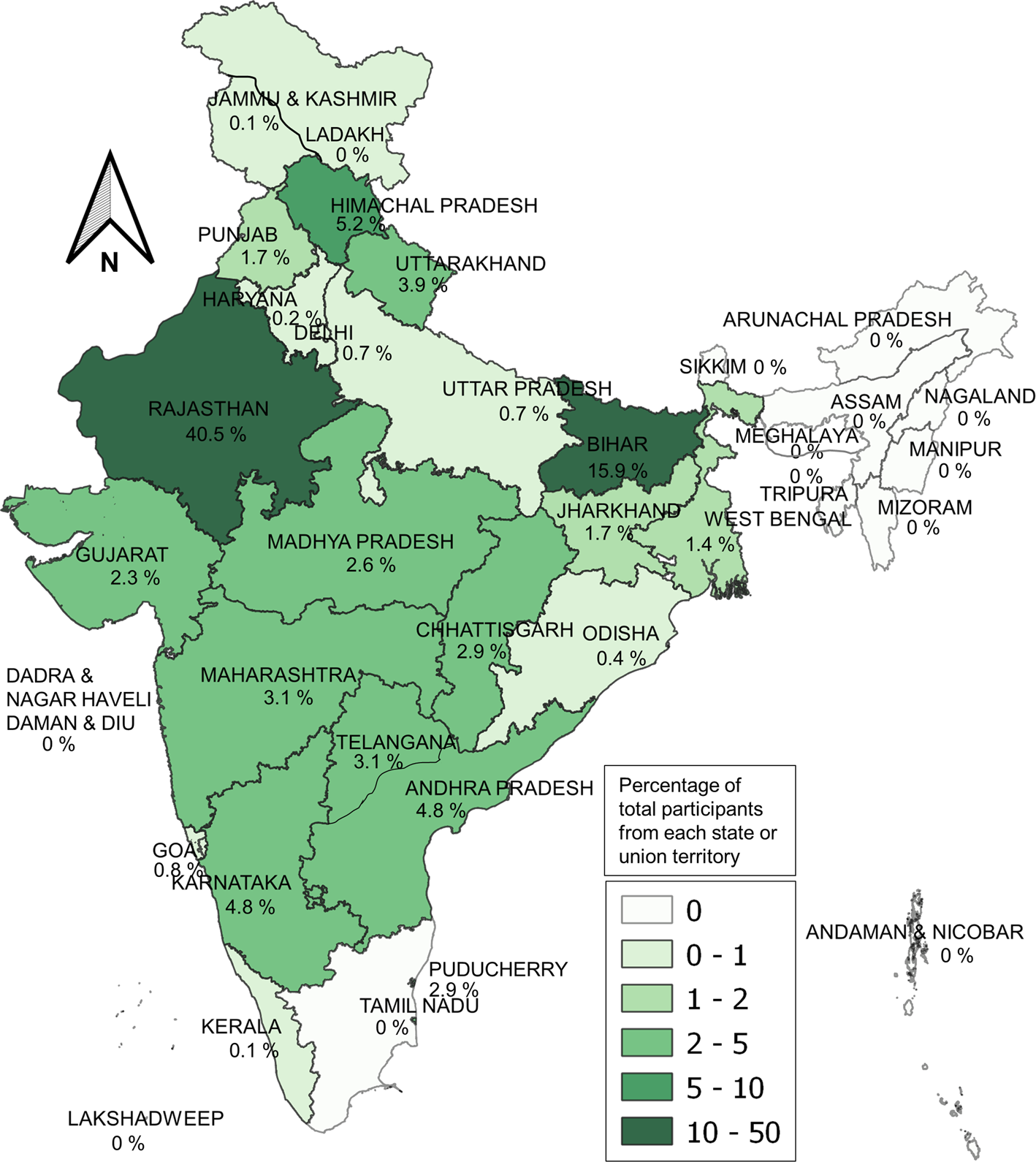

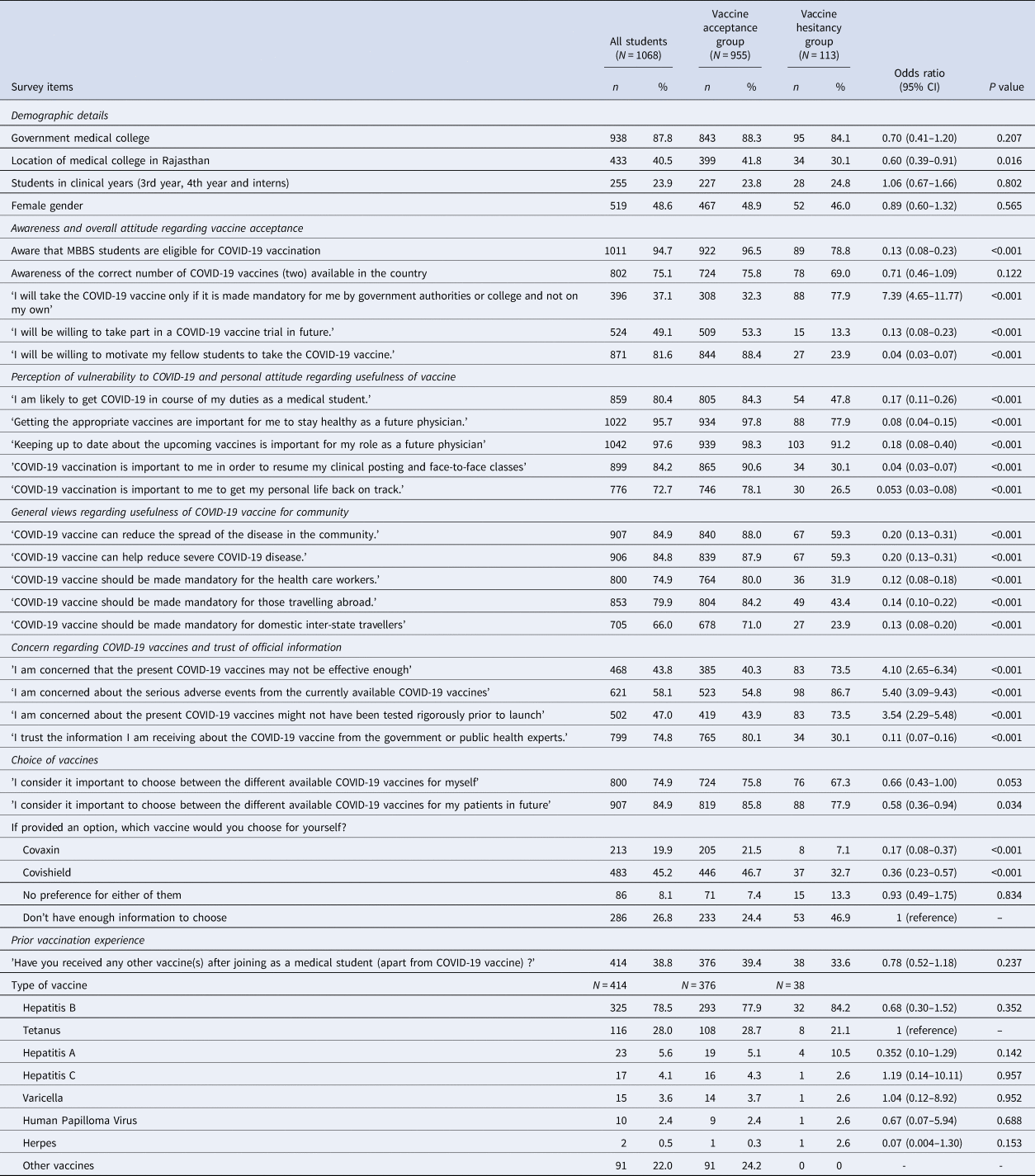

A total of 1068 students from 22 states and union territories of India participated in the online survey (Fig. 1). Around two-fifths of students were from Rajasthan state (Table 1). Gender of students was almost equally distributed (48.6% females). Nearly one-fourths students were studying in the clinical part of the MBBS course (Table 1). The data collected for the study is included in Supplementary file 2.

Fig. 1. State/Union territory-wise participation of medical students in the COVID-19 vaccine survey in India (n = 1068).

Table 1. Responses of medical students belonging to vaccine acceptance and hesitance groups (N = 1068)

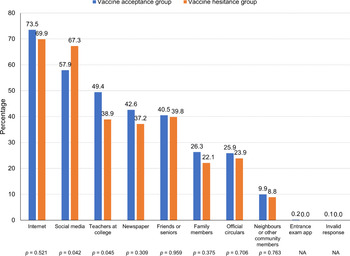

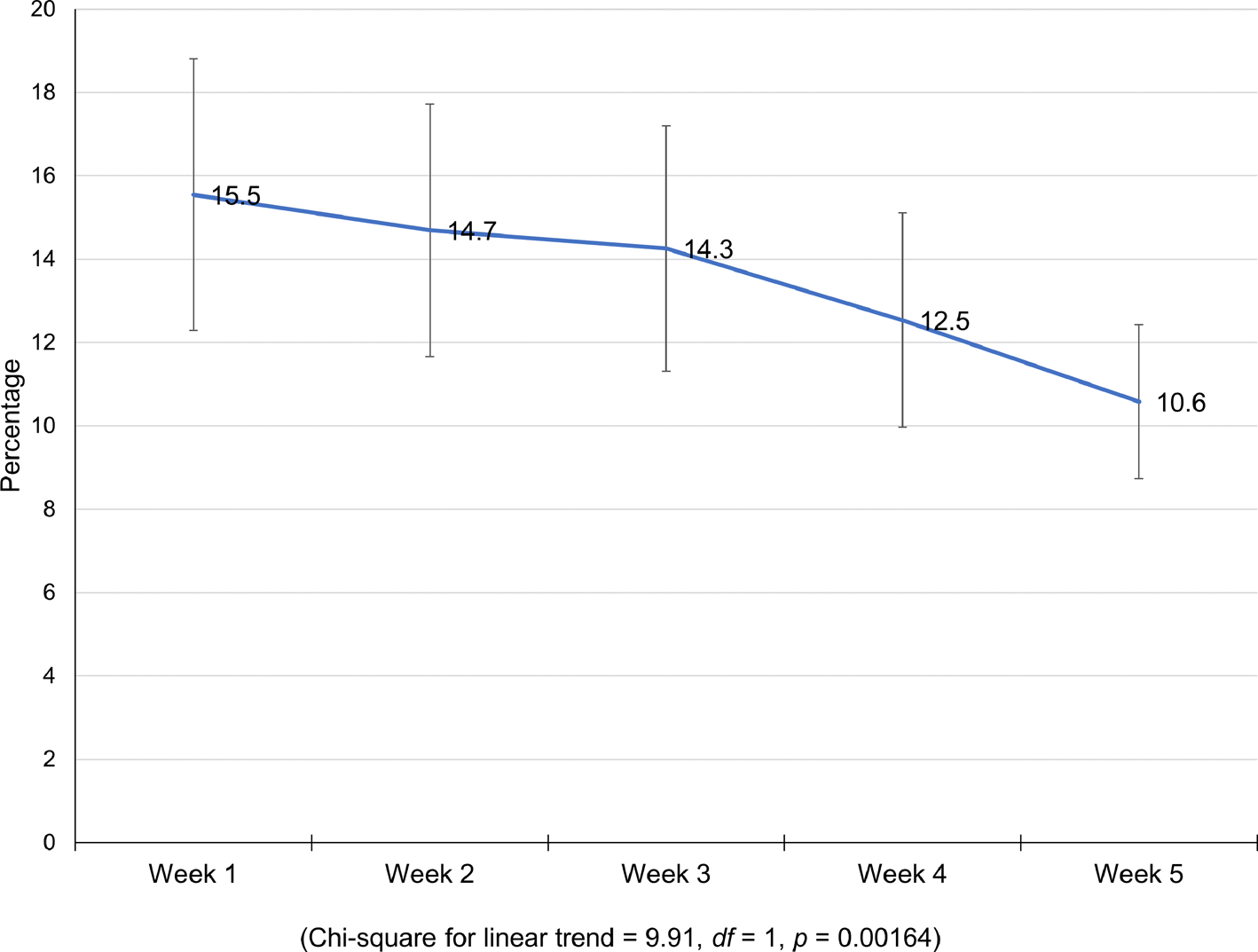

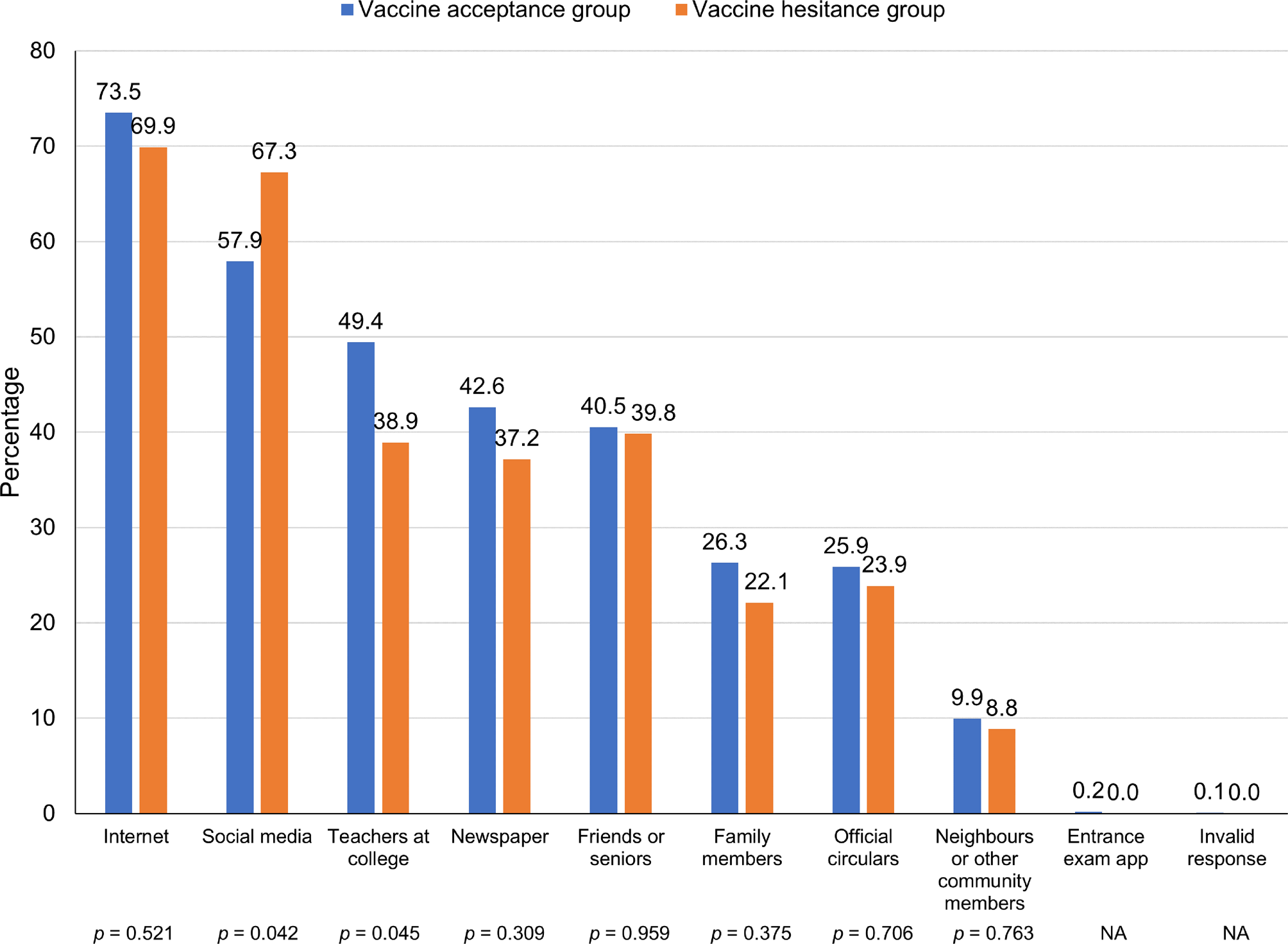

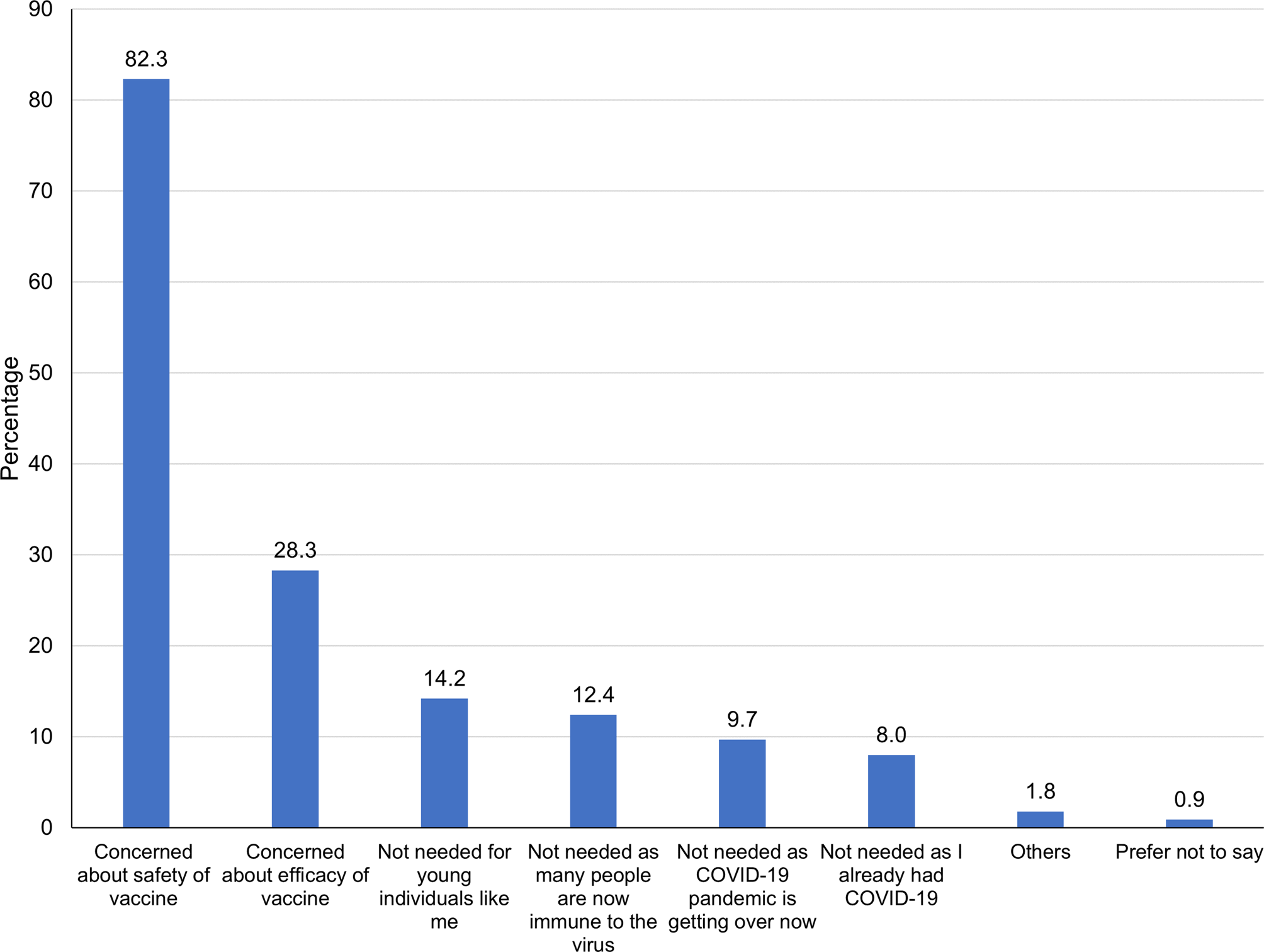

In response to the statement ‘I am willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine when offered’, 43 (4.0%) ‘disagreed’ and 70 (6.6%) were ‘not sure’. Therefore, vaccine hesitancy was found among 113 students (10.6%). Among those who agreed, 689 (64.5%) had already taken the vaccine and 266 (24.9%) were yet to receive the vaccine at the time of responding to the survey. Out of the possible responses of 'yes', 'not sure' and 'no', those responding 'yes' have been cross-tabulated in Table 1 based on whether they accepted the COVID-19 vaccine or hesitated to take it. Cumulative vaccine hesitancy based on the online responses showed a significant declining trend (P = 0.00164) from 15.5% at the end of the first week of the survey to 10.6% at the end of the fifth week (Fig. 2). Internet, social media and teachers at medical colleges were the most common source of information regarding COVID-19 vaccine for both the vaccine hesitance and acceptance groups (Fig. 3). Further, we found that larger proportion of vaccine-hesitant students obtained vaccine-related information from social media, as compared to those accepting vaccines (Fig. 3). On the other hand, lesser vaccine-hesitant students had teachers at medical college as their source of vaccine-related information (Fig. 3). Concern regarding safety of COVID-19 vaccine followed by concern regarding its efficacy was the most common reason cited by those hesitant to take the vaccine (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Week-wise trend of cumulative COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among surveyed medical students.

Fig. 3. Sources of information regarding COVID-19 vaccine for the medical students belonging to vaccine hesitance and vaccine acceptance groups (n = 1068).

Fig. 4. Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the medical students (n = 113).

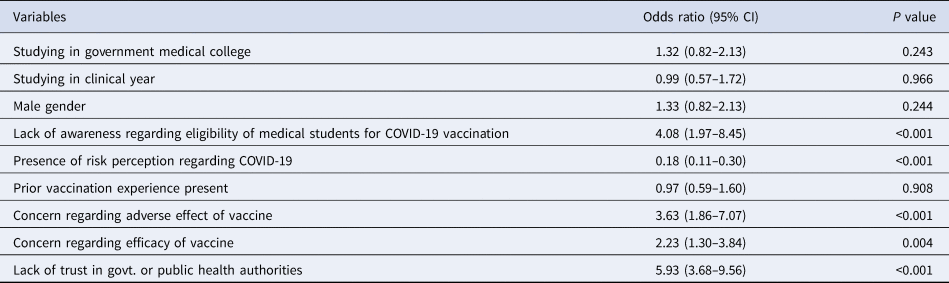

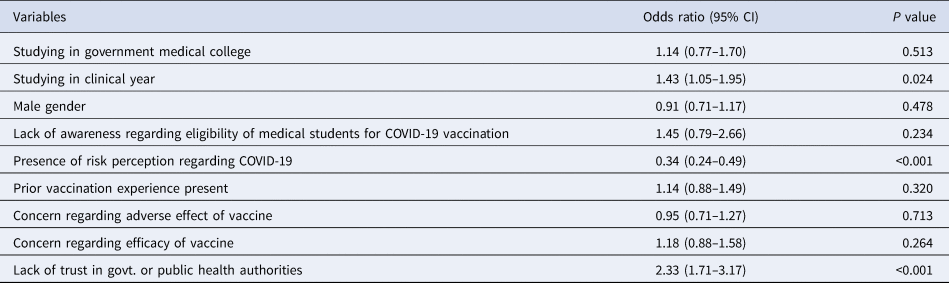

Upon conducting logistic regression, lack of awareness of medical students regarding their COVID-19 vaccine eligibility, concern regarding vaccine safety and efficacy and lack of trust in public health authorities were associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (Table 2). Hesitation in joining COVID-19 vaccine trial was predicted by lack of trust in government or public health authorities (Table 3). Conversely, the presence of risk perception among students regarding themselves getting affected by COVID-19 was associated with lesser hesitancy in receiving COVID-19 vaccine as well as for participating in COVID-19 vaccine trials (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Multivariable logistic regression for plausible determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (N = 1068)

Model parameters: Log likelihood = −247.59, minus 2 log likelihood difference vs. intercept = 226.05, df = 9, P < 0.0001. Pseudo R 2 = 0.3134.

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression for plausible determinants of hesitancy regarding participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials (N = 1068)

Model parameters: Log likelihood = −691.08, minus 2 log likelihood difference vs. intercept = 98.03, df = 9, P < 0.0001. Pseudo R 2 = 0.0662.

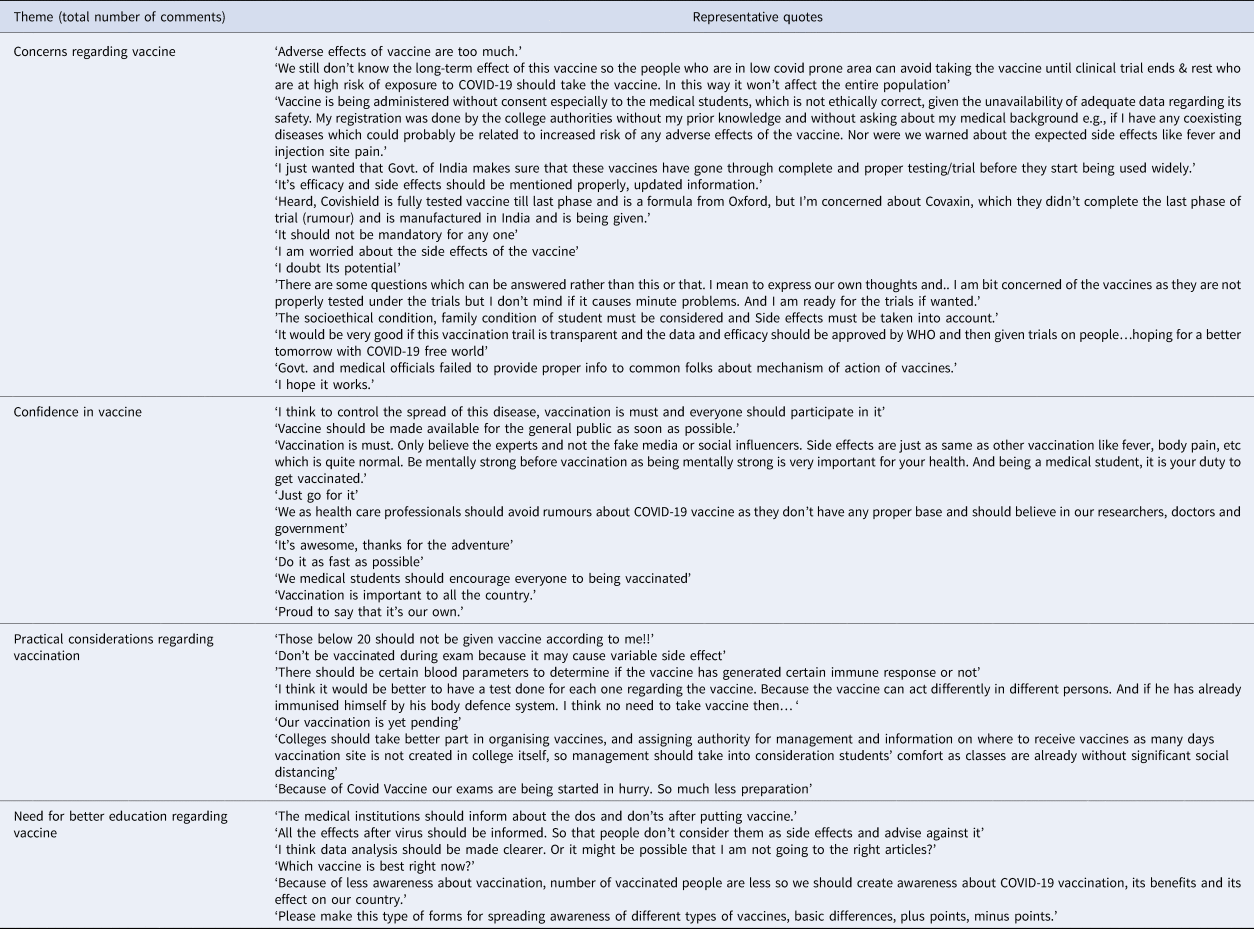

Comments by medical students were arranged in four themes – ‘confidence in vaccine’, ‘concern regarding vaccine’, ‘practical considerations’ and ‘need for better education’ (Table 4).

Table 4. Comments provided by medical students regarding COVID-19 vaccine

Discussion

Awareness of COVID-19 vaccine and sources of information

COVID-19 vaccination provides a renewed opportunity to closely study the dynamics of health-related behaviour change in a well-informed young adult population. We found that better awareness regarding the COVID-19 vaccine was associated with reduced hesitancy, similar to study conducted earlier [Reference Paterson8]. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy reduced over time in our study, which has also been observed earlier [Reference Mo22, Reference Nguyen23]. COVID-19 vaccine uptake, especially among young college students has been explained through diffusion of innovation theory through openness to experience and adoption of descriptive norm [Reference Mo22]. Innovators and early adopters of COVID-19 vaccination could play a role in facilitating its wider acceptance in the medical student community [24].

The views of students should also be seen in relation to the matrix of multiple sources of information available to them. Our findings support that the role of internet and social media as an information source of health behaviours has been increasingly important for medical students [Reference Afonso20]. Any future intervention to reduce vaccine hesitancy among the student population should take into account this realignment of sources of information. Contribution of social media as a source of information was significantly greater among vaccine-hesitant students, which could be explained by unverified and potentially misleading information promoted by anti-vaccination groups [Reference Wilson and Wiysonge25, Reference Hotez26]. Therefore, we recommend countering this by systematic promotion of more reliable sources of information such as through peers, teachers and official websites.

Determinants of vaccine hesitancy

Adoption of vaccination practices by healthcare workers plays a key role in motivating the general population through setting an example [Reference Manning10, Reference Szmyd27]. Concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccine adverse events as a possible reason for hesitancy has been highlighted by most studies concerning university students, health care workers and in the general population [Reference Manning10–Reference Qiao13, Reference Saied18, Reference Shekhar28]. Further, concerns regarding vaccine efficacy were also seen to limit the adoption of the COVID-19 vaccine [Reference Manning10, Reference Taylor11, Reference Saied18, Reference Shekhar28]. The real concern regarding adverse events appeared to be from the possible ‘long term’ effect of the vaccine. This was coupled with the apprehension that the vaccines had not been tested rigorously enough to determine all possible adverse events and efficacy in a proper manner. The short-term adverse events were also inconveniencing the students owing to vaccination sessions held close to their examinations. The concern regarding vaccine adverse events and efficacy were further elaborated by the comments provided by students. Additionally, concern of lack of consent for provision of data for registration of COVID-19 vaccine by medical students was also observed.

Our findings also seemed to match with the health belief model [24] wherein the perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 and perceived benefits of vaccination had a role in reducing the hesitancy for COVID-19 vaccination. We also found that a sizeable proportion of students had indeed received the vaccination despite having concerns which indicated that acceptance of vaccination was not purely voluntary. It appears unlikely that this coercion could be entirely driven by pressure from college authorities. Within this framework, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance could have been a subjective norm and pressure of social conformity could have influenced some hesitant students to finally get vaccinated. Further, majority of those choosing to be vaccinated were motivated by desire for resumption of clinical and face-to-face classes and by the prospect of getting their personal lives back on track. Therefore, COVID-19 vaccination was also seen a confidence building measure which could help the students ease their restricted life during COVID-19 pandemic. Confidence regarding the vaccine was also expressed by the students through free comments. On the other hand, those hesitating were much less likely to believe in this enabling effect of COVID-19 vaccination.

Hesitancy for participation in COVID-19 vaccine trials

Concern for adverse events did not deter medical students to participate in vaccine trials unlike their counterparts in the United States of America [Reference Lucia, Kelekar and Afonso12]. Risk perception of self-regarding COVID-19 increased the students’ willingness to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trial. On the other hand, lack of trust in government or public health authorities deterred them from participating in vaccine trials, similar to what was observed in previous studies [Reference Lucia, Kelekar and Afonso12, Reference Fisher29, Reference Sun, Lin and Operario30].

Attitudes regarding COVID-19 vaccine mandates

Overall, more than three-fourths medical students viewed that COVID-19 vaccine should be made mandatory for both health care workers and international travellers. However, those hesitating to take COVID-19 vaccination were also less convinced about the various aspects of usefulness of the vaccine for the community such as its potential in reducing the spread of infection or severe COVID-19 disease. They were also much less likely to have it mandated for health care workers and domestic and international travellers. Majority of even those hesitating displayed a sense of responsibility in their role as future physicians to keep up to date regarding the upcoming vaccines and their importance in keeping themselves healthy. This suggests that hesitation regarding COVID-19 vaccination could be related to issues specific to it rather than due to apathy towards vaccines in general. Therefore, targeted education and trust building by regulatory agencies and medical colleges could considerably reduce COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students.

Choice of vaccines and previous vaccination

Students considered it important to choose between the available COVID-19 vaccines both for themselves and for their future patients. Between the two available vaccines, Covishield was preferred whereas a considerable proportion also felt that they did not have enough information to choose. Acceptance of Covaxin was found to be less in general and was even lesser among those hesitating to take the vaccine. This situation might change in future with more information on safety and efficacy of vaccines being available.

Experience of prior vaccination has been found to have a role in increasing the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine [Reference Fisher29, Reference Pastorino31]. However, this was not replicated in the present study. This could be mainly because in the present setting, Hepatitis-B was the vaccine taken by majority of the students unlike the studies from outside India in which annual Influenza vaccination had been considered [Reference Fisher29, Reference Pastorino31]. Since the importance of Hepatitis B vaccine is well-accepted for healthcare professionals, its uptake might be more related to medical colleges’ policy of offering vaccination to medical students during their course rather than vaccine hesitancy per se.

Limitations

Our survey had the limitation that it was conducted after COVID-19 vaccination had started in some of the medical colleges. Therefore, it could have underestimated the initial vaccine hesitancy of those who subsequently converted to the vaccine acceptance group and were ultimately vaccinated. Since participation in this survey was based on peer-to-peer communication through social media networks, the denominator for calculation of response rate could not be determined. Due to the non-probability sampling approach in the study, the generalisability of vaccine hesitancy among medical students across India would need to be further informed by the local context. We also did not specifically ask about scientific journals as a source of vaccine information. Although we captured students’ responses through open comments, the online mode of data collection often fails to capture the depth of information which could otherwise have been possible through qualitative methods applied in face-to-face settings.

Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy was found in one out of every 10 medical students. Lack of awareness regarding vaccination eligibility, concern regarding adverse events and efficacy of the vaccine and lack of trust in government were independently predictive of vaccine hesitancy. Heightened risk perception regarding COVID-19 seemed to reduce vaccine hesitancy. Concerns regarding lack of vaccine-related information and launch of vaccine prior to release of safety and efficacy data were noted. Although vaccine hesitancy showed a diminishing trend over time, health education programmes tailored to boost awareness regarding vaccine and improve trust in government agencies would be helpful. Focus should be on promoting official sources of information to counter apprehension generated through social media use. Taking due informed consent for registration of personal information in vaccine portal and ensuring that vaccination sessions are not held just before examinations could further improve acceptance of newly launched vaccines. As future health care providers, concerns of medical students should be addressed on priority.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268821001205

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the help of medical students who participated in the study.

Author contributions

JJ conceived the idea of the study. JJ and SS designed the data collection format with inputs from MKG, PB. JJ, PK, MKV and SS conducted data collection. SS wrote the manuscript with inputs from JJ, MKG, PB, AG, MKV, PK and PRR. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

The authors declare that no funding was received from any source for the study and preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest for publication of this article. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the views of their organisations.

Ethical standards

The study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) – Jodhpur, India (Ref: AIIMS/IEC/2021/3438).

Data availability statement

Data file upon which the study findings are based is included as Supplementary file 2.