Introduction

In early medieval literature, warriors are typically associated with a specific weapon, which is part of their heroic identity (Webster, Reference Webster, Mitchell and Robinson1998). Often, such weapons are named and their history—the warriors who have carried them and the battles they were used in—is recounted like that of a hero (Culbert, Reference Culbert1960; Khanmohamadi, Reference Khanmohamadi2017). Although many types of weapons are mythologized in this way, swords are the most common. Similarly, the archaeological record suggests that swords interweave a series of cultural, personal and physical relations (Ingold, Reference Ingold2010; Paz, 2017; Lund, Reference Lund2017). Medieval swords are not physically or socially static objects. Their shape was altered with use and they were often adapted by swapping hilts, guards, or wrapping. Swords were typically owned by several people in the course of their use and this contributed to the construction of their identities (Brunning, Reference Brunning2013, Reference Brunning, Semple, Orsini and Mui2017). Swords require close quarter combat, so sword fighting is, by its nature, more personal and intimate and, perhaps for that reason, swords seem to carry memories, imbuing them with ancestral qualities. They become the agents in stories, defining status, generating events and creating or recreating identities (Kopytoff, Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986; van Houts, Reference van Houts1999; Williams, Reference Williams2005). In both the literary and the archaeological records, it appears that swords, like warriors, gained status with age and deeds; interestingly, in literature, swords are only buried after a long career or if there is no heir to claim them, an idea that appears reflected in the archaeological evidence. Here, swords deposited among grave-goods tend to be old, or at least were considered old when they were put into the ground (Brunning, 2019). Buried swords are also frequently associated with status in the interpretation of Early Anglo-Saxon and Viking graves (Härke, Reference Härke, Theuws and Nelson2000; Hadley, Reference Hadley, Crawford and Hamerow2008). Rather than being contradictory, archaeology and literature used together can deepen our understanding of swords and the construction of particular personhoods in the Early Middle Ages.

This article takes an innovative methodological approach, not only by combining archaeological and literary evidence, but also in its approach to this evidence. We use archaeological evidence to discuss the location of swords in burials and, more importantly, to explore personhood as presented in the mortuary context. This expression of personhood manifests itself in the merging of the body with swords within a performative context since the objects were positioned by mourners who had to climb into the grave themselves, which the literary evidence helps to illuminate. Poetry has sometimes been seen a problematic source of evidence since it only describes mortuary contexts incidentally (Price, Reference Price, Price and Brink2008). However, it is this very quality which makes it an excellent source for examining social expectations. Although literature recounts extraordinary events, it must reflect familiar customs, attitudes, and assumptions in order to engage its audience. Identifying these allows us to explore the context and narrative construction which engenders mortuary performance (Price, Reference Price2010).

Our study of the physical association between individuals and swords is based here on Anglo-Saxon and Viking-age contexts in the UK and Scandinavia. This geographical focus complements the locations which the literature discussed here recalls, and it also allows us to explore the interaction between body and weapon in graves from different cultural contexts. We examine the intersection of persons and swords by exploring how they were used to construct identities in poetry and intermingle with archaeological bodies. Swords are often examined as objects; however, we contend that in both literature and archaeology swords were associated with a person, inseparably intermeshed with a particular identity; their presence in a narrative or in the grave was part of the emotive context, contingent on social and personal circumstances.

Weapons are pluralistic objects, both functional and capable of wounding and killing, but also embodying values associated with identity, personhood, gender, and age. A sword is thus a practical, semiotic and symbolic object. It is a status symbol, a badge of class or group membership, and, since it takes practice to use, it changes the person it encounters (Kopytoff, Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986). Swords are transformative and used alongside other material culture in the construction and performance of an individual (Martin, Reference Martin, Blinkhorn and Cumberbatch2014; Felder, Reference Felder2015; Harrison, Reference Harrison, Barrett and Gibbon2015). Similarly debates about personhood encapsulate the aesthetic body, material, and semiotic relationships (Fowler, Reference Fowler2010a). Today, shoes which take on the shape of the body and are used in sports, social performance, sexualized behaviour, and as markers of rites of passage or class may be a reasonable analogy. A skateboarder might repair a shoe with tape or glue in certain spots, a practical response to damage, but this is also a semiotic act allowing one accomplished skateboarder to recognize another (Steele, Reference Steele1998). Another analogue might be found in the fact that a charismatic or eccentric personality may ‘get away with’ odd combinations of clothing, e.g. white trainers and a suit, where as a business or civic leader could not (Hockey et al., Reference Hockey, Dilley, Robinson and Sherlock2013; Reference Hockey, Dilley, Robinson and Sherlock2015). In the right combination objects can produce an empowering aesthetic which embodies and expresses cultural values seen in art, literature, and storytelling. Specific non-human things can be described using enigmatic, multi-layered or animistic language through which they can be ascribed person-like or empowering qualities (Paz, 2017; Lund, Reference Lund2017).

Swords in Anglo-Saxon Literature

Swords have a specific status in Anglo-Saxon literature. In Irish, Welsh, and Scandinavian literature, names are recorded for spears, axes, and other weapons, such as Gáe Bulga, the spear of the Irish hero, Cúchulainn, or the Norwegian King Magnus’ axe Hel. However, in Anglo-Saxon literature only swords bear names. The tendency to anthropomorphize is most clearly demonstrated in the Anglo-Saxon riddles on swords which always imagine them as warriors. Tatwine's eighth-century riddle, De Ense et Vagina, describes the sword as having ‘cordis compagine’ (l. 1), the ‘heart of a warrior’, while the sword in Aldhelm's riddle De Pugione vel Spada (also eighth century) says ‘domini…nitor defendere vitam’ (l. 5) ‘I fight to defend the life of my lord’. In the Exeter Book (of which the earliest extant copy dates to the tenth century, though the texts may well be earlier) there are two sword riddles. The sword in riddle 80 describes itself ‘Ic eom æþelinges eaxlgestealla’ (K-D 80, l. 1), ‘I am a warrior's shoulder-companion’, a term that is usually used of a fellow warrior, while the sword in riddle 20 says it follows a ‘waldend’, a lord (though the word literally means ‘wielder’) and that:

‘oft ic gæstberend

cwelle compwæpnu cyning mec gyrweð

since ℸ seolfre ℸ mec on sele weorþað’ (K-D 20, l. 8b–10)

(‘often I kill men with war weapons. The king adorns me with jewels and silver and praises me in the hall’).

Here, again, the sword is being described in exactly the same terms that a warrior would typically be described in heroic poetry. Interestingly, the reference to being adorned is repeated throughout the riddle, suggesting that it is part of the idea of a sword that it is altered and decorated, especially after victories, so that each alteration would contribute to the sword's history.

Swords are not only anthropomorphized, they are depicted almost as though they have a character and agency. For example, in the dragon fight in the seventh- or eighth-century poem Beowulf (Neidorf, Reference Neidorf2016), the hero's sword is described almost as though it were a person, with moral responsibilities: it ‘geswac/ nacod æt niðe swa hyt no sceoldes’ (Beo. l. 2584b–5) (‘failed as it should not have done, naked in violence’). Often, swords are introduced in more detail than heroes. When Wiglaf joins Beowulf at the crucial moment in the fight against the dragon, he is introduced in two and a half lines:

‘Wiglaf wæs haten Weoxstanes sunu

leoflic lindwiga leod Scylfinga

maeg Ælfheres’ (Beo. l. 2602–2604a)

(‘He was called Wiglaf, Weohstan's son, dear shield-fighter, man of the Scyldings, Ælfhere's kin’).

By contrast, his sword's history is given more than five times as many lines and the poet includes both the story of how the sword came into the possession of Wiglaf's family and to Wiglaf himself. This emphasis on the heritage of swords is pervasive: ‘ealde lafe’ (Beo. l. 795b; 1488b; 1688a) (‘old heirlooms), ‘gomelra lafe’ (l. 2563), (‘ancient heirlooms’) and even by the compounds ‘ealdsweord’ (Beo. l. 1558a; 1663a; 2616a; 2979a and Mal. l. 46), (‘old-sword’), ‘gomelswyrd’ (Beo. l. 2610 b), (‘ancient-sword’) and ‘yrfelafe’ (Beo. l. 1903 a) (‘old heirloom’). The literature reveals a belief that swords are hardened and improved by use in battle: ‘waepen wundum heard’ (Beo. l. 2687b) (‘weapons hardened by wounds’), so that an old sword, passed down from previous battles and tested in combat, is regarded as better and more trustworthy than a new sword. This attitude is even found in the tenth-century poem Battle of Maldon: the Anglo-Saxon leader, Brythnoth taunts the messenger of the attacking Vikings:

‘Hi willað eow to gafole garas syllan

ættrynne ord and ealde swurd’ (Mal 1. 46–7)

(‘They will pay you a tribute of good spears, deadly barbs and old swords’).

Unlike the other weapons listed here (spears and arrows), the defining and best quality in a sword is that it is old, which presumably implies that it has been gifted, or passed down. Moreover, one of the words for ‘sword’ in poetry is laf which means ‘heirloom’; this word is not used as a term for any other kind of object, and it therefore seems to convey a sword's specific emotional and symbolic significance. There is even a notion that warriors can be ‘waepnum gewurþad’ (Beo. l. 331a) ‘made worthy by weapons’; when Beowulf and his men arrive at the Danish court, the herald recommends that the king see them because ‘hy on wiggetawum wyrðe þinceað/ eorla geæhtlan’ (Beo. l. 368–9a) ‘from their war-gear, they seem worthy of the esteem of warriors’. Beowulf himself gives the Danish watchman a sword ‘þæt h syðþan wæs/ on meodubence maþma þy weorþre/ yrfelafe’ (Beo. l. 1901–1903a) (‘so that afterwards on the meadbenches, he had more honoured because of the old heirloom’.

In some contexts, inheriting a sword may even be the mark of a warrior, as the case of Wiglaf demonstrates. His father, Weohstan,

‘frætwe geheold fela missera

bill ond byrnan oð ðæt his byre mihte

eorlscipe efnan swa his aerfæder·

geaf him ða mid Geatum guðgewaeda

aeghwæs unrim þa he of ealdre gewat’ (l. 2620–2624)

(‘…held the treasures for many years—the sword and armour—until his son became a warrior like his old father. Then, among the Geats, he gave him the war-gear, much and of many kinds. Then he left this life’).

This attitude is not only found in literary but also in documentary texts. Athelstan's will (980s–1014 ce) records a bequest to his brother, the future King Edmund (before 990s–1016 ce), of a sword (apparently) centuries old; ‘þæs swurdes þe Offa cyng ahte’, ‘the sword that King Offa had’ (Tollerton, Reference Tollerton2011), in what seems to have been an endorsement of his future leadership (Danet & Bogoch, Reference Danet, Bogoch and Gibbons1994).

Perhaps the most interesting demonstration of the symbolic power of swords is when Beowulf predicts the failure of Hroðgar's truce. He imagines one Heathobard saying to another:

‘Meaht ðu, min wine, mece gecnawan

þone þin fæder to gefeohte bær

under heregriman hindeman siðe,

dyre iren, þær hyne Dene slogon,

weoldon wælstowe, syððan Wiðergyld læg,

æfter hæleþa hryre, hwate Scyldungas?’ (Beo. l. 2047–2052)

(‘Can you, my friend, recognize the blade which your father bore into battle, beneath his helmet on his last campaign, the precious iron sword—where the Danes killed him, conquered on the battlefield, once Withergyld fell, after the warriors’ defeat, the valiant Scyldings?’)

The assumption is that a warrior who sees another carrying his father's sword will seek revenge. This sword has greater symbolism than the father's killing alone and motivates a hereditary agency in which a son seeks to restore his father's legacy. The death does not prevent the warrior from making and accepting the truce but the sight of a former enemy carrying the sword ensures the warrior will break the treaty (Sebo, Reference Sebo2011).

Swords in Scandinavian Literature

Although other kinds of war-gear are named in Scandinavian heroic literature, here too swords are the dominant heroic weapon. As in the Anglo-Saxon literature, a battle-tested sword is a more certain proposition in the heat of battle, where untested weapons are something of a gamble. Consequently, the (typically young) living hero reclaiming an old sword (usually from the less-than-enthusiastic resident of a burial mound) is a common trope in the sagas. Not all weapons need to be won this way, however, and swords gain additional significance when handed down, from one accomplished or notable warrior to another. This action has the effect of bestowing the sword's pedigree and virtue to its new owner, confirming an heir's status or connecting an outsider to an illustrious tradition.

Perhaps the most obvious example of such a sword is the cursed Tyrfingr, whose creation is detailed in the Poetic Edda, and whose tragic career is charted in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks and the supporting material. Interestingly, Tyrfingr is more important as a symbol than as a weapon at the beginning of Hervarar saga. It is taken as a spoil of war and then passed down. The shield maiden Hervǫr, in her quest to avenge her father Angantyr, traces reports of his death to the island of Samsey, where she takes the unusual step of calling him out of his burial mound to demand the sword: ‘Trauðr ertu / arf at veita / eingabarni.’ (Hervarar saga, ch. 4) ‘You are slow to give that inheritance to your only child’. It is clear from Hervǫr's choice of words, and specifically from her use of arfr, ‘inheritance,’ that she views Tyrfingr as her birthright, even though it has not explicitly been declared so. Despite his reluctance, Angantyr acknowledges the validity of her claim. The sword belongs to Hervǫr, as the representative of that family and as her father's heir and avenger, and it will do so for the rest of her career as a warrior until it is passed on down through her family. Perhaps more interestingly, Tyrfingr is cursed to kill every time it is drawn and to commit three evil deeds. In practice, this means Tyrfingr kills many of its owners, a feature which imbues it with a kind of personhood.

Weapons also have a particular significance as gifts, depending of the status and relationship of those engaged in the exchange. Here the weapon, whether or not it has a name already, may be referred to in the same manner as other important gifts: by a compound name made up of the giver's forename and the ending -nautr, ‘gift.’ Thus, for example, the sword Skefilsnautr, in Reykdœla saga, is recognized as the sword given by Skefill (in this case, to the warrior Þorkell Geirason). A -nautr weapon is more than a gift, it is an extension of the giver and embodies a sort of emotional or symbolic connection between giver and recipient, gaining a character of its own (Miller, Reference Miller2007). In Reykdœla saga, for example, Þorkell returns a sword taken from the warrior Skefill's grave that he had used to kill a rival; he is visited the following night by the spirit of the dead Skefill. Skefill praises him for his achievement, and ultimately offers the weapon on the grounds that ‘ek þarf þat nú ekki, enn þú ert svá vaskr maðr at ek ann þér allvel at njóta.’ (Reyk, 67) ‘I don't need it now, and you are so valiant a man that I am wholly pleased that you should have it.’ When Þorkell wakes the next morning, the weapon is by his side, a token of esteem and a symbol of achievement from one dead hero to a living one.

Other Kinds of Weapons in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian Literature

In a few instances, warriors are defined by weapons other than swords. However, this generally indicates something about the nature of the hero, that he is unconventional in some way. The most obvious Anglo-Saxon example is Beowulf, who, unlike his men, is not ‘waepnum gewurþad’ (Beo. 331a) ‘made worthy by his weapons’, and who is regarded as a hondbana, a warrior who kills with his bare hands (Sebo, Reference Sebo2011). Although he is associated with a least six different swords, some of which he gives as gifts, the three he uses during the course of the poem fail, and the poet says:

‘Him þæt gifeðe ne wæs

þæt him irenna ecge mihton

helpan æt hilde; wæs sio hond to strong,

se ðe meca gehwane, mine gefræge,

swenge ofersohte’ (2682b–6a).

(‘It was not his fate that the edge of iron weapons could help in battle—his hand was too strong—that every blade, as I have heard, he overtaxed).

Instead, his characteristic war-gear is the armour made by Weland that belonged to Hrethel and saves his life against Grendel's Mother; he asks for it to be returned to his lord if he dies fighting Grendel, and wishes he could leave to a son as he is dying.

Although swords are also the norm in medieval Scandinavian literature, here there is a much greater variety of significant weapons. Perhaps the most notable example is Njála’s Gunnarr Hámundarson's atgeirr (a spear or pole weapon). Like Beowulf, Gunnarr's unconventional choice of signature weapon indicates his freakish capacities. He is not only strong and large, but explicitly ‘manna bezt vígr,’ (Njála, 53) ‘the best of men in combat,’ unmatched in games or feats of arms, capable of such fighting with either hand, and able to achieve such outlandish feats as being able to leap, fully encumbered, more than his own height, swim like a seal, and swing a sword so quickly that ‘at þrjú þóttu á lopti at sjá’ (Njála, 53) ‘it appeared that there were three [swords] in the air [at once]’.

Similarly, while it may not possess the long and illustrious pedigree of more famous named weapons, the origins of Gunnarr's atgeirr suggest that it stands apart from other weapons. Originally the possession of the warrior Hallgrímr, the unnamed atgeirr is said to have been ‘látit seiða til’ (Njála, 80), ‘wound about with sorcery’ to prevent Hallgrímr from being killed by anything but the weapon itself. It is likewise thought to be able to foretell death, singing aloud or ringing out when someone is about to be killed by it. Indeed, while it may not have an identifying name, Gunnarr's atgeirr can be said (with a mostly unintentional pun) to ‘speak for itself.’ In 51 references to the weapon, each time (save for its introduction and one attribution as ‘Gunnarr's atgeirr’), the definite form is used—atgeirinn—in place of the more customary use of the indefinite for an unnamed weapon (Orkisz, Reference Orkisz2016, p.187). It is simply ‘the atgeirr,’ as there is no question who it belongs to, or who it is characteristic of.

Although he retains his other weapons, the atgeirr, from the time of Gunnarr's claim onwards, is inseparable from the man himself. It marks him apart from his many luckless rivals, and, perhaps more importantly, it remains onstage after his death, to act as an indicator of his son Hǫgni's eventual succession to the heroic mode when he avenges his father. Gunnarr's mother, Rannveig, takes the interesting step of refusing to bury the weapon with her son, declaring that it must be passed down, though only to the one who takes vengeance. There is, of course, no more suitable candidate than Hǫgni, who, of Gunnarr's two sons, is the most like him, if slightly less motivated to feats of valour. The atgeirr becomes his nudge into that world, a final gift from Gunnarr, who had previously made his presence manifest in the burial mound apparently to spur on his son. When Hǫgni goes to retrieve the weapon, it responds in clear fashion:

‘Hǫgni tekr ofan atgeirinn, ok song í honum. Rannveig spratt upp at œði mikilli ok spurði: “Hverr tekr atgeirinn, þar er ek bannaða ǫllum með at fara?” “Ek ætla,” segir Hǫgni, “at fœra fǫður mínum, ok hafi hann til Valhallar ok beri þar fram á vápnaþingi.” “Fyrri muntú nú bera hann ok hefna fǫður þíns,” segir hon, “því at atgeirrinn segir manns bana, eins eða fleiri”’ (Njála, 194).

(‘Hǫgni took down the atgeirr, and it sang out. Rannveig sprang up in a great anger and asked: “Who is taking the atgeirr, when I forbade anyone from taking it away?” “I intend,” said Hǫgni, “to bring it to my father, so that he can have it in Valhalla and take it to battle.” “First you will bear it now, and avenge your father,” she said, “because that atgeirr announces death, for one man or more”’).

While not explicitly bequeathed from father to son, the ringing of the atgeirr in this moment recalls both the weapon's supernatural origins and aspects, and their manifestations twice at pivotal moments in the life of Gunnarr. It is no coincidence that, following Gunnarr's death, his mother subverts expected tradition and expressly forbids the burial of the weapon with its owner; this was the moment that she was waiting for. Hǫgni's removal of it, and use in fulfilment of Rannveig's wishes, signifies a change in ownership similar to that effected by Gunnarr's own taking possession of it, and when the son exits the saga following this final act of vengeance, he takes with him his father's weapon and legacy.

The Materiality of Early Medieval Swords

The literature suggests that swords both become identified with their owner and that the swords are identifiable. Consequently, the decoration and wear visible on a sword is significant. As Brunning (Reference Brunning2013; Reference Brunning, Semple, Orsini and Mui2017) argues, wear makes a sword unique, visually identifiable, and gives it a life-history, or even ‘person-like’ qualities. For example, the sixth-century silver-gilt ring-pommel from grave 39 at the cemetery at Bifrons in Kent has lost its surface gilding, while the sword from grave C at Dover Buckland (also in Kent) shows signs of heavy wear and marking at the apex of the pommel from being worn (Brunning, Reference Brunning, Semple, Orsini and Mui2017: 441). Other examples include swords from the Kentish sites of Broadstairs, Sarre, Faversham, and Saltwood, as well as Scandinavian swords, including those from boat grave XII at Vendel, and both swords from grave 6 at Valsgärde in Sweden (Brunning, Reference Brunning2013: 123–25). These differences reflect each specific, symbiotic relationship. Swords wear with contact which differs depending on the physical dimensions and biomechanics of the carrier, and on how and if the sword is worn. Grips, naturally, also wear differently depending on their construction, composition, wrapping, use, and user. For example, the sword from boat grave I at Vendel shows evidence of wear from use on its metal handle (Brunning, Reference Brunning2013: 128). The user's body also adapts, developing calluses, muscle, or new habits of movement to accommodate the sword. In these ways, a sword becomes part of the person, aesthetically associated with them, and physically adapted in a form of relational personhood (Fowler, Reference Fowler, Garrow and Yarrow2010b). Given this symbiotic relationship, it is not surprising that early medieval literature reflects a sense that inherited swords carry with them part of their previous owner. In other words, a weapon can convey intergenerational agency. Gunnarr Hamundarson's weapon, the atgeirr, has this broader significance: it is taken up by his son in order to seek vengeance, not just a spear but also as a tool to continue an intergenerational feud. In fact, this narrative implies that the feud could have ended if no one had taken up the atgeirr. The next generation seems to have had some choice, a feature reflected in several Germanic legal codes (Jurasinski, Reference Jurasinski2006; Sebo, Reference Sebo, Wilcox, Jorgensen and McCormack2015). Similarly, Hrómundr's sword is not just simply a trophy, it helps him secure marriage and join a royal family.

The literature also stresses the value placed on old swords, an element which is reflected in a range of ways in the archaeological record. Tania Dickinson, for example, noted that the fittings on the sword in grave 31 at Brighthampton (Oxfordshire) were not stylistically consistent: ‘the deep chip-carved scabbard mouth is quite different from the chape with its plane, plated ornament, and both are distinct from the neat equal-armed silver cross which ornamented the scabbard’ (Dickinson, Reference Dickinson1976: 258). This sword, like that from grave 11 at Petersfinger near Salisbury and Chessell Down on the Isle of Wight (Hawkes & Page, Reference Hawkes and Page1967: 11–16), was a composite consisting of parts made through the fifth and early sixth century. Similarly, the Staffordshire Hoard includes a series of parts of sword hilts, deposited at the same time but some of which were over 200 years old (Fischer & Soulat, Reference Fischer and Soulat2008; Mortimer & Davis, Reference Mortimer, Davies, Mortimer and Munker2018). Old swords, then, had particular value—so much so that, in some cases, recycled fittings were used to give the appearance of age. In addition, the identification of old or reused scabbards and their fittings suggest that every part of a sword could be retained or recycled (Brunning, Reference Brunning2013: 38). For example, some have their rings removed, presumably with a change in ownership or stewardship (see Evison, Reference Evison1967: 63; Brunning, Reference Brunning, Semple, Orsini and Mui2017). Swords were worn, modified, and used objects, and although the majority we have seem to have been deposited in contemporary mortuary contexts, these are probably only a small proportion of the swords in circulation (Härke, Reference Härke, Theuws and Nelson2000).

Swords and Bodies in Early Anglo-Saxon Burials

We cannot know if early medieval swords had names like the swords in poetry (Brunning, Reference Brunning2013: 42; Mortimer & Davis, Reference Mortimer, Davies, Mortimer and Munker2018). However, in the use and wear of a weapon there is an amalgamation of body and sword, making a direct connection between the material object and the person, their identity and how they looked and were presented. This intermeshing of weapon and person is also seen in Early Anglo-Saxon mortuary contexts. To illustrate this, we have investigated Early Anglo-Saxon as well as Viking-age burials.

Burials

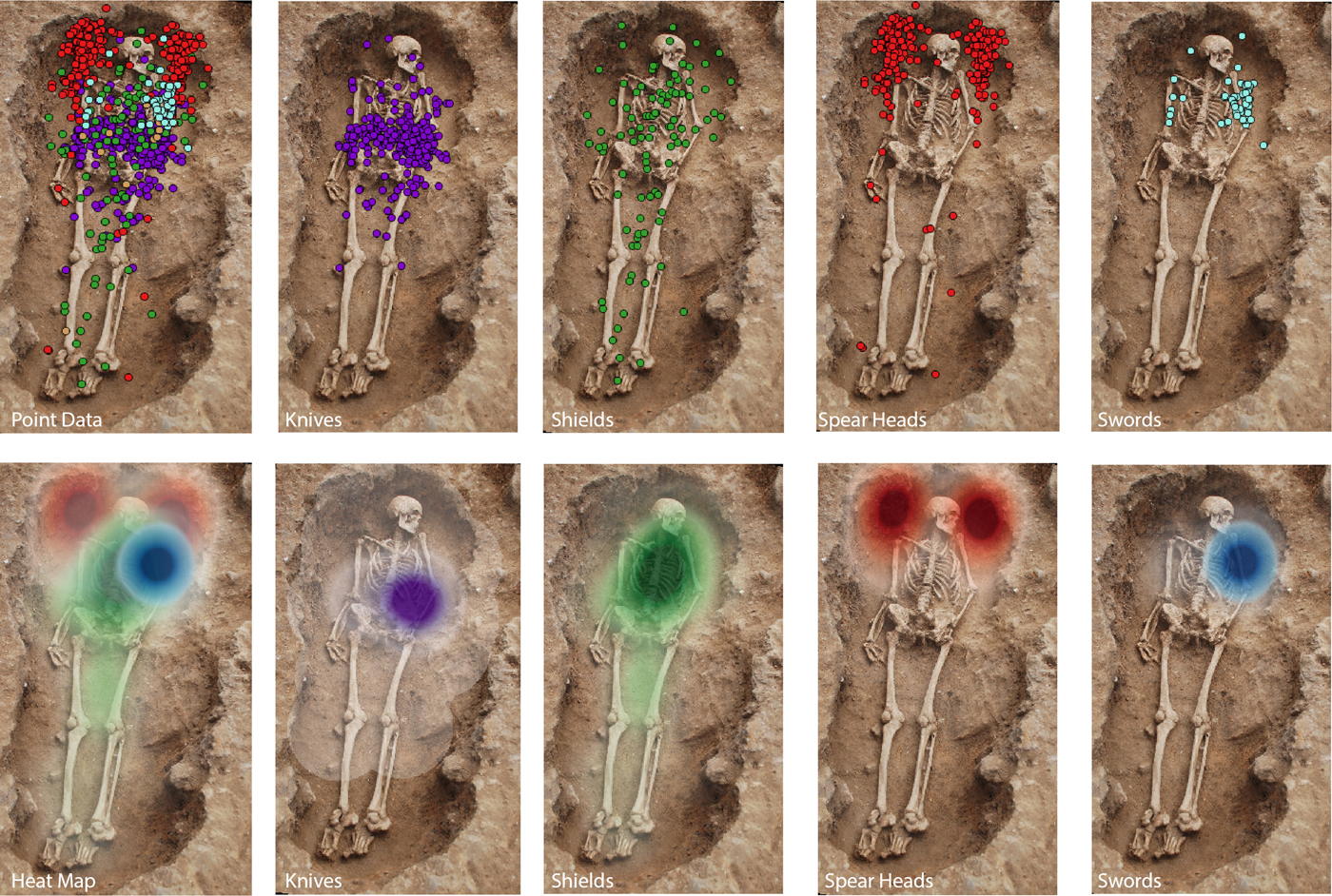

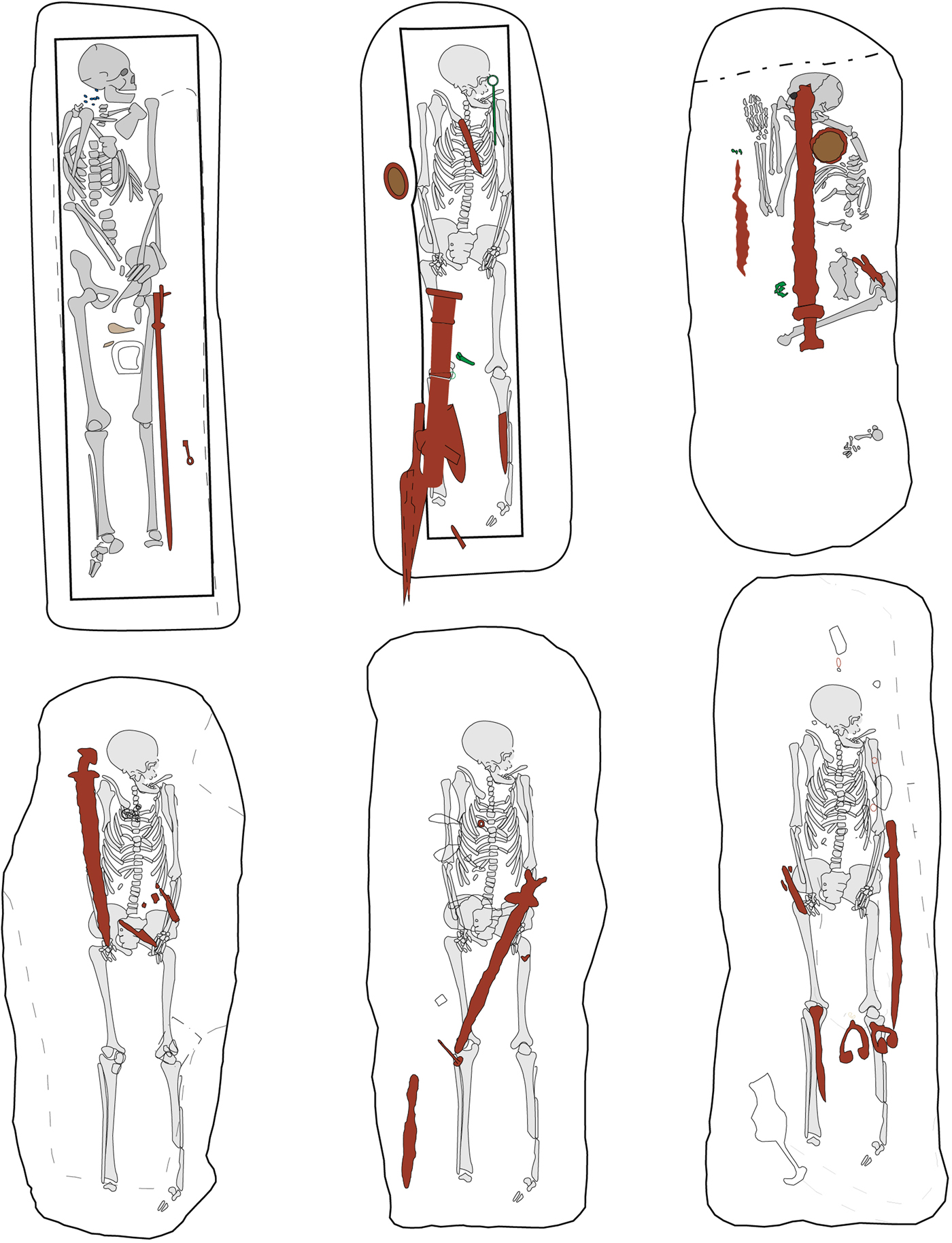

This project builds on the work of Härke (Reference Härke1992: 125–29) who plotted weapon locations onto a gridded representation of the grave in order to identify some patterning in the placement of shields and spears. To extend this and achieve a more nuanced impression of weapon locations we decided to apply GIS tools to locate each object relative to the grave and body. Initially, 407 weapons and 470 knives from seventeen Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries were located within a spatially referenced Early Anglo-Saxon grave. For swords or knives, the point plotted was the intersection between the handle and the blade; for spears it was the junction of the socket and the blade; and for a shield boss the middle of the boss. This point marks the position these objects as found in their original burial, and it highlights not only their proximity of the weapons to the body but their relationship to it as well (Figure 1 and Table 1). A photograph of a grave without grave-goods was also spatially referenced within GIS. This image provides a good visual aid to understand the relative location of weapons to the person. The photograph used is of a supine individual since the majority (84 per cent) of weapon burials were supine inhumations (Mui, Reference Mui2018: 119). This photograph can be used as a good approximation of the original body position. There is some slight variation, however, in the arm position. In the photograph, the individual's left shoulder is raised. The point data for spears traces a shoulder shape just below and to the right of the photographed shoulder. This was the location of most of shoulders. There is also some regional variation in body positioning with most variation evident in the north east of Britain, particularly at West Heslerton in North Yorkshire, a site included in this study (Mui, Reference Mui2018: 105).

Figure 1. The location of weapons and knives found in 17 Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. The point data are along the top, and along the bottom, a heat map plotted at 0.5 m, showing the area of highest density for each object, including: knives (purple), shields (green), spearheads (red), and swords (blue). Knives are concentrated on the left hip, shields along the body, spears to either side of the head, and swords were found with the hilt at shoulder and head height. Each point represents the intersection between the blade and the handle or for the shield its centre.

Table 1. Number of knives and weapons form Early Anglo-Saxon sites used in this study.

Position of other weapons: knives, spears and shields

Knives are found in both male and female graves (Härke, Reference Härke1989) and, although they are found in a number of different positions (including the waist area, legs, chest, shoulders, and arms), the vast majority are found around the left hip: 314 of the 470 (67 per cent) knives are found around the left hip, with 81 knives (17 per cent) in the area of the right hip and 75 (16 per cent) elsewhere (Figure 2). Knives were an accessory of Early Anglo-Saxon dress, probably associated with a belt around the waist area (Owen-Crocker, Reference Owen-Crocker1986: 80). Spears, by contrast, seem to have been positioned in equal numbers on either the right- or left-hand side of the body: there are 120 (48.6 per cent) on the left, 125 (50.6 per cent) on the right, and 2 (0.9 per cent) in the middle. These figures do not seem to relate to right- or left-handedness and so should not be understood as reproducing how a spear was used or seen in association with the person. Most of these spearheads (227, or 92 per cent) where positioned around the shoulder or neck area and, significantly, the majority were outside the line of the body and arms, not placed across them. Shields were found in a variety of places: 19 (19 per cent) outside the body area, 25 (25.5 per cent) over the legs, and 47 (48 per cent) over the torso, meaning that 74.5 per cent were over the body, and, if the shield board was narrow (see the horseman shown holding a small shield on the Sutton Hoo helmet, and the Pliezhausen (Baden-Württemberg) bracteates for illustrations of narrow shield boards), they need not have hidden the face. Shields provide protection for the body and, perhaps, were placed last amongst the objects, concluding access to the body and sheltering it from the soil which would fill the grave (Figure 1).

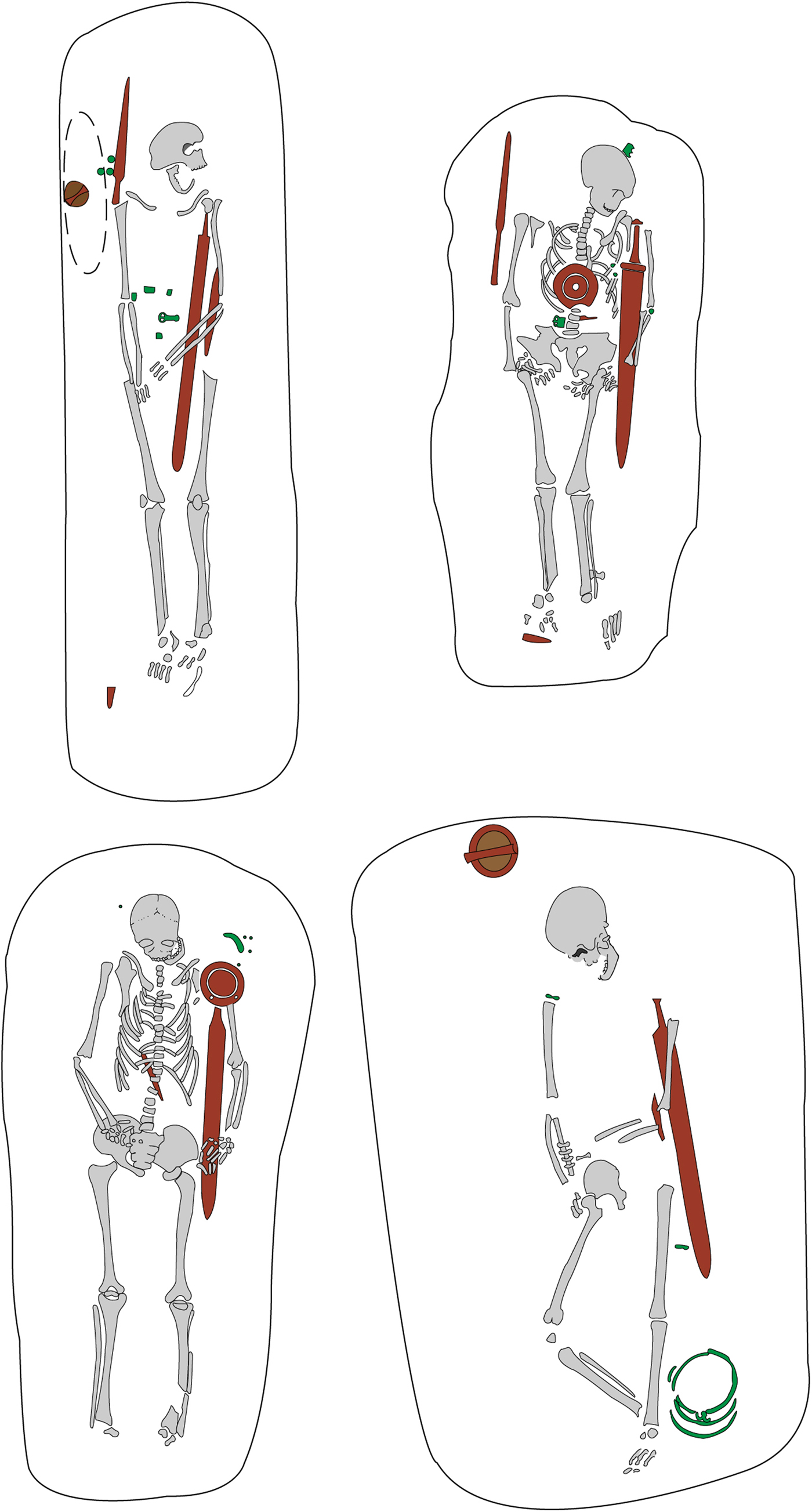

Figure 2. Four graves in which the person was placed embracing their sword. Top left: Dover Buckland grave 56; top right: Blacknall Field grave 22; bottom left: Blacknall Field grave 70; bottom right: Westgarth Gardens grave 66.

Position of swords

Swords, unlike knives, were not worn when buried; rather they were placed alongside the body, as demonstrated by Brunning's (Reference Brunning2013: 150–51) study of 97 Kentish swords. In her sample, 47 per cent were directly beside the body; 25 per cent placed completely or partially on the body, 16 per cent touched or were touched by the body, and 7 per cent were cradled. In total, 95 per cent interacted directly with the deceased. In our investigation of 51 swords we found a similar association, with just three weapons placed away from the body. The majority, 44 (or 86 per cent) were placed on the left-hand side, with the handle and hilt towards the top of the grave. This position implies an intermeshing with the body as lived, not just the corpse, because it corresponds to proportions of left or right handedness. Seven swords were found on the right (14 per cent), which corresponds roughly with the expected proportion of left-handedness (around 10 or 20 per cent). Here the sword is placed on the side it was worn, rather than near the hand that used it. Interestingly, however, this laterality is not seen in the placement of spears or shields—weapons which do not appear to have the same connection to the person of the dead. Moreover, swords are found adjacent to the torso, either inside or just outside the arm position, and not at the waist, hip, or hand. Swords are not displayed in the grave as they were worn on the body, as knives are, but rather they are intertwined with the body. They are a separate object accompanying the person—in some cases individuals were even buried embracing their sword (Figure 2).

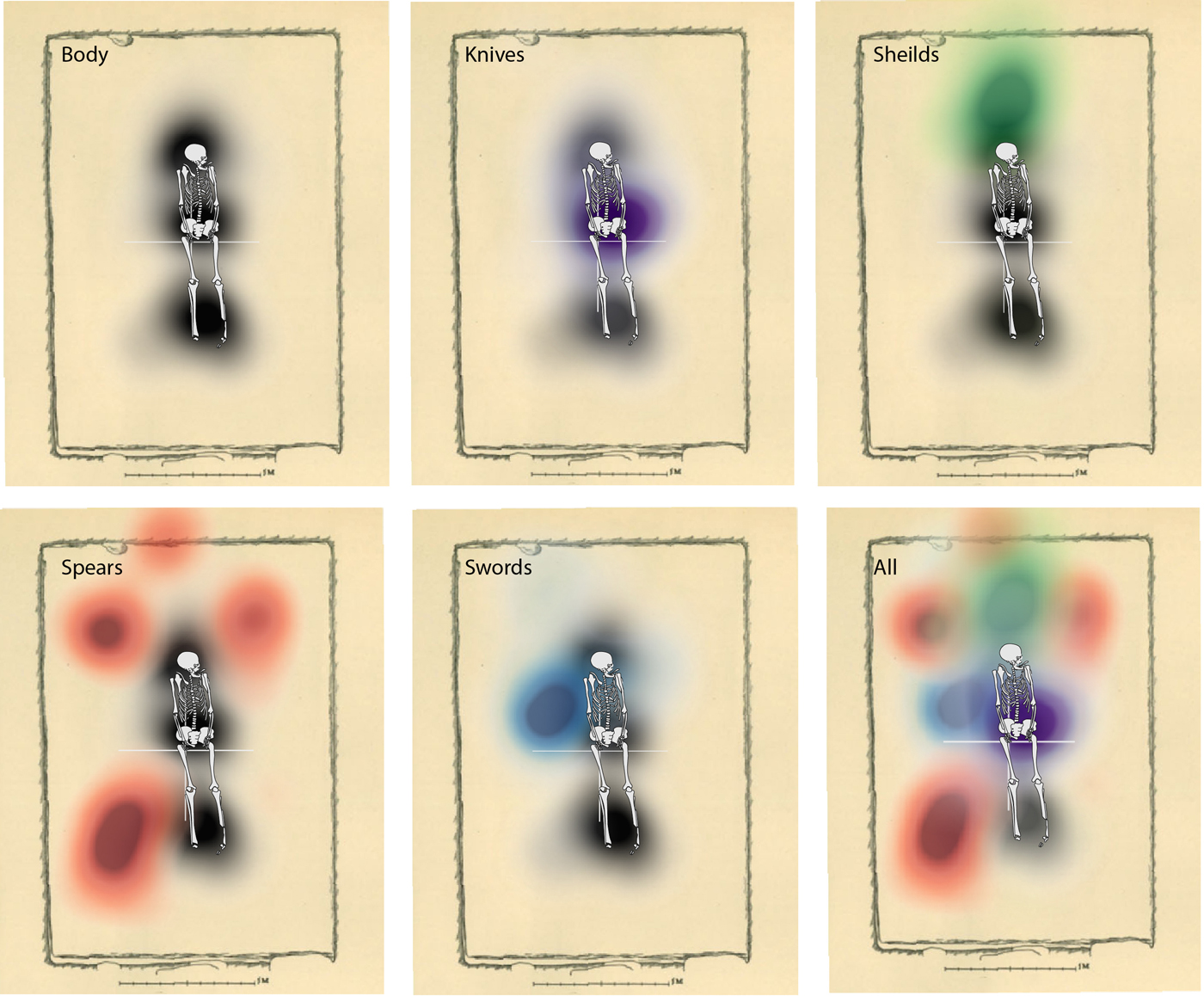

Chamber burials

It is instructive to compare these results from fifth- to seventh-century inhumations to those of seventh-century burial chambers. Since these are larger, it is possible for swords to be placed further from the body. However, most are still placed in direct association. In mound 17 at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, where soil discoloration marks the location of the body even though it had largely disintegrated, the sword was placed with the person, just as in early inhumations. This was apparently accompanied by a buckle, knife, and purse at the hilt, suggesting it had a belt attached, but not worn (Carver, Reference Carver2005: 129). The sword was on the person's right-hand side, with the hilt and grip parallel to the shoulder. In mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, the sword was at shoulder height, placed directly on top and to the right-hand side of a coffin (Carver, Reference Carver2005: 182–95) (Figure 3). Similarly, according to the 1883 sketch of the Taplow burial, the sword is on the right-hand side placed high up, hilt and grip alongside the person's head, or on top of a coffin enclosing the body (Stevens, Reference Stevens1884). The chambered grave at Prittlewell in Essex is an interesting exception to this arrangement since here the sword was placed away from the body at 90 degrees to it, on the chamber floor, with the blade facing outwards and the hilt oriented towards the coffin (Hirst, Reference Hirst2004). Nevertheless, there is an association between sword and body.

Figure 3. Anglo-Saxon princely burials. Top left: Taplow; top right: Sutton Hoo, mound 1; bottom: Prittlewell. After Stevens, Reference Clark1884 (Taplow), Carver, Reference Carver2005: 182 (Sutton Hoo) and Hirst, 2004 (Prittlewell). In each case human skeletons have been drawn within the coffin to illustrate the relationship between the sword and the body.

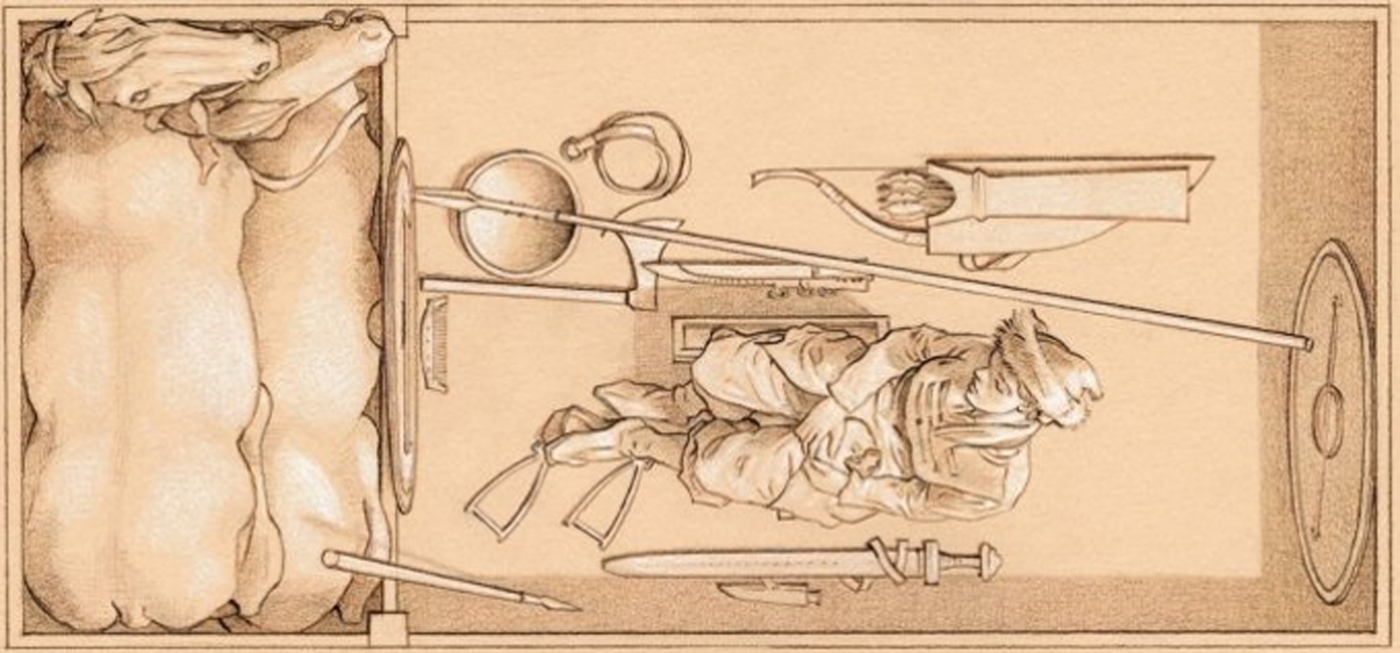

Swords and Bodies in Viking Age Burials

The Early Anglo-Saxon placement of the sword with the body, and particularly its proximity to the shoulders, head, and face, is not universally replicated by later Viking-age burials in Britain, though the association of the sword with the body remains important. Soil conditions mean that there are not comparable numbers of Viking-age sword graves. However, from those that exist, there seems to have been much more variation in burial practice than is evident in Early Anglo-Saxon cases. Grave 511 at Repton, Derbyshire, has a sword on the left of the body with the hilt at the hip, suggesting that the weapon was placed as if worn on the body when buried (Biddle & Kjølbye-Biddle, Reference Biddle and Kjølbye-Biddle1992; see Figure 4). Similarly, the grave at Ballateare on the Isle of Man has a sword low down in the coffin on the right-hand side of where the body would have been, presumably worn on the front of a belt or placed in the grave as if worn and turned outwards facing a funerary audience (Wilson, Reference Wilson2008: 31). Each of the three sword burials at Cumwhitton, Cumbria, seemed to have had different sword positions in relation to the body, though the disintegration of the bodies makes it impossible to be certain (Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Parsons, Newman, Johnson and Howard Davis2014; see Figure 4). Grave 25 has the sword to the centre left of the grave, adjacent to the body, worn or placed as worn in the grave. In grave 36, the sword is also on the left of the grave, around the middle, but the blade crosses where the body would have been. In grave 24, the sword is placed alongside the shoulder, so that the hilt would have been next to the face. Interestingly, in the Papa Westray burial on Orkney, the sword was placed on top of the body, turned around so that its tip concealed the person's temple and jaw, with the hilt over the lower thigh. Given the location of the shield boss, the sword is likely to have been placed alongside or on top of the shield, mimicking the position of the body below and representing the individual whose face was concealed under the shield. These burials probably date to between the eighth and tenth centuries (Hadley, Reference Hadley2006: 241–44).

Figure 4. Six Viking-age graves with swords. Top row, left to right: Repton grave 511, Ballateare, and Papa Westray. Both Repton and Ballateare may have been in coffins. The bottom row shows from left to right: Cumwhitton graves 24, 36, and 25. The Ballateare and Cumwhitton graves have had human skeletons superimposed to highlight the different sword positions and how they may have interacted with the body. After Biddle & Kjølbye-Biddle, 1992 (Repton); Wilson, Reference Wilson2008: 31 (Ballateare); McLaren, Reference McLaren2016 (Papa Westray); Paterson, et al Reference Paterson, Parsons, Newman, Johnson and Howard Davis2014 (Cumwhitton).

Viking-age boat burials

In Viking Age boat burials, there is a tendency to place the sword next to the body. At Ardnamurchan in the Highlands of Scotland, the sword was placed parallel on the left-hand side of the body (based on teeth survival), with the hilt at head height (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Cobb, Batey, Beaumont, Montgomery and Gray2017). Similarly, at Westness on the island of Rousay in the Orkneys (Figure 5), a sword was found on the right-hand side, although, in this case, a little away from the body. The body itself was placed to the left of the central axis of the boat, uniting the visual aesthetic of sword and body. This funerary tableau was constructed to position the body and sword as equal parts of an aesthetic whole across the centre of the boat (). The boat burial at Kaldárhöfði, Iceland, contained the poorly-preserved remains of two individuals, an adult and a child. The boat was quite small, with the weapons mostly found outside of it. However, based on the orientation deduced from teeth survival, the sword was placed with its hilt in closest proximity to the adult's head and shoulder (McGuire, Reference McGuire2009: 160–61). Finally, the multiple burial in a boat at Scar on the island of Sanday in Orkney also contained a sword associated with a specific individual. The person buried with this weapon was at the prow of the boat, on its left side, slightly flexed, and with a sword along the line of the person's spine. The sword seems to have been placed high along the individual's back, with the hilt at what was probably shoulder and head height. As this survey makes clear, there was a greater range of positions evident in Viking-age burial. From these few examples, it may be inferred that the sword was frequently worn, or placed as if worn, but also that it remained a component of the identity of the deceased.

Figure 5. Viking-age boat burial at Westness, Rousay. The white cross provides a central point of reference: the human remains and sword are placed on either side of the central point creating and aesthetic balance. This boat burial was excavated by Norsk Arkeologisk Selskap (Wilson & Hurst, Reference Wilson and Hurst1969: 242).

Chamber burials

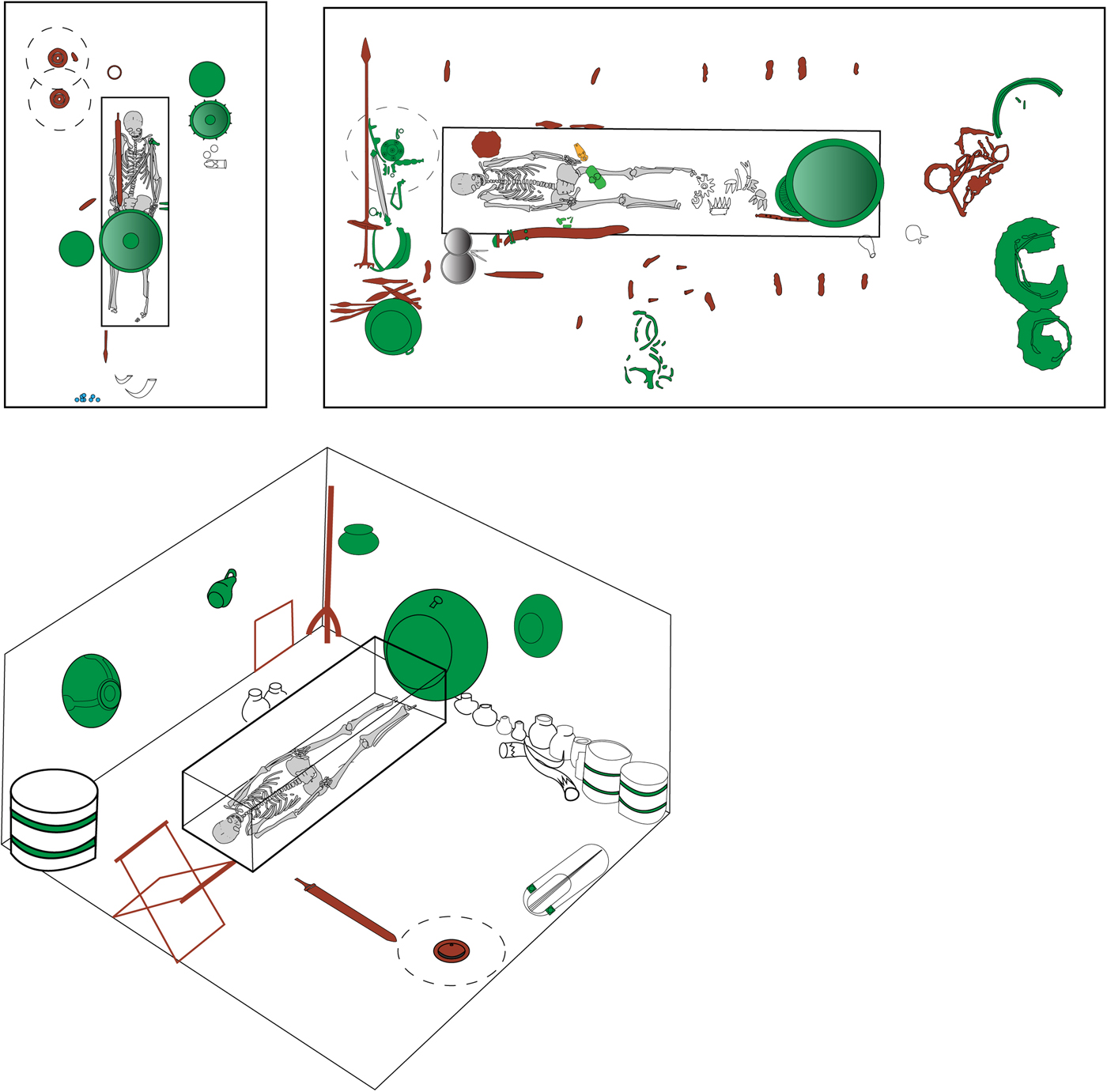

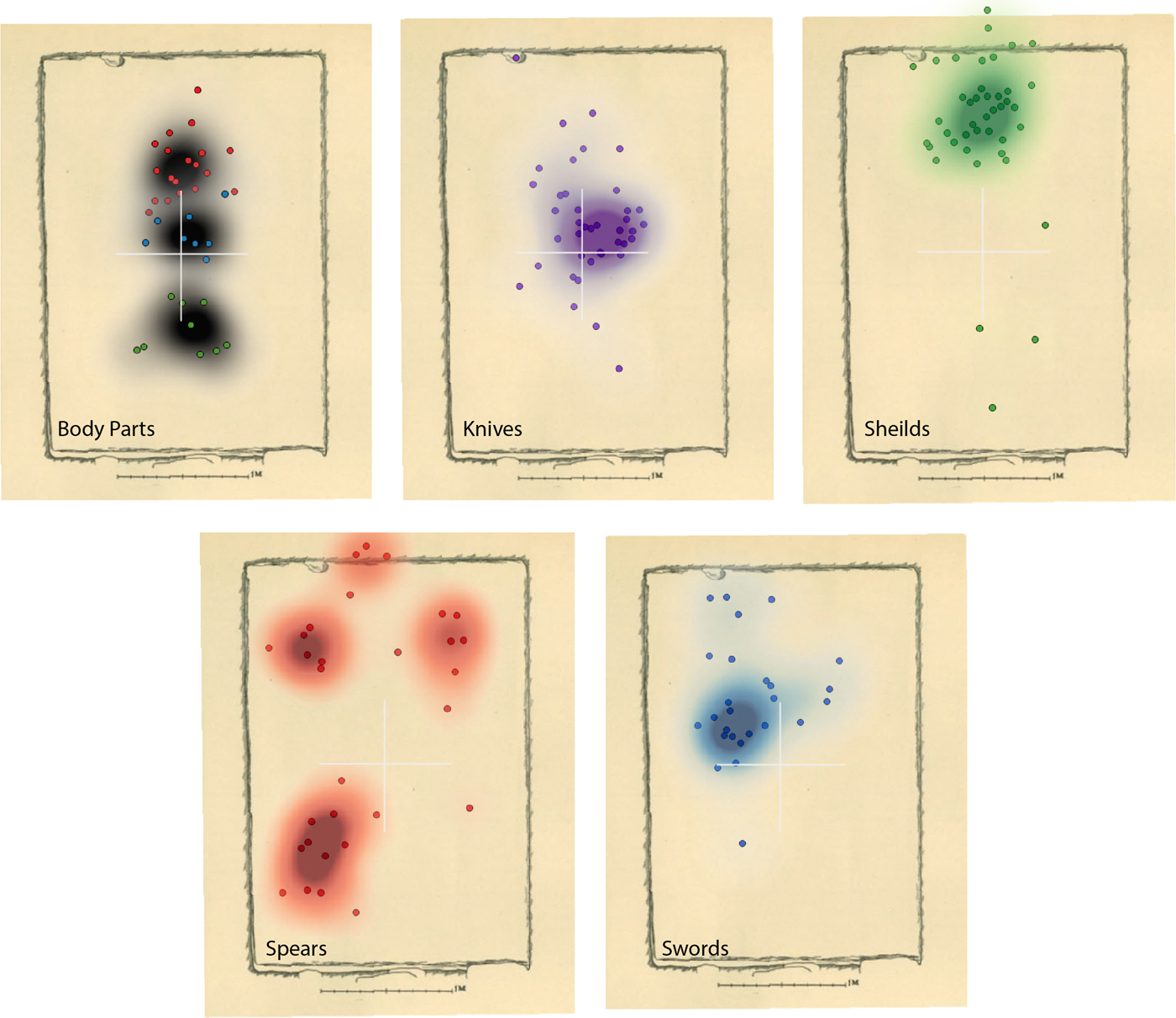

This significance in the placement of swords in Viking-age burials is also seen in the ninth- and tenth-century chamber burials at Birka in Sweden. For this study, we looked at the internal layout of 39 chamber graves, based on Arbman's (Reference Arbman1943) notes and illustrations, with a particular focus on the location of swords, spears, shields, and knives. Unfortunately, as with the Viking-age burials in the UK and Iceland, human remains are typically poorly preserved. Each of these 39 chambers has a different size and shape, although they are all roughly rectangular. To facilitate comparison of these spaces, the central point of each chamber was measured and spatially referenced. The relative location of each object and the evidence for the head (skull or teeth), pelvis (pelvis or upper femur), or feet (feet or lower legs) of the deceased could be recorded in relation to this central point which then allowed comparison. The locations of these human remains were plotted onto the georeferenced chamber, and their clustering suggest that bodies were predominantly placed with the head to the north, the pelvis in the centre, and the legs to the south of the chamber. To aid visualisation, an illustration of a skeleton was placed within the chamber with its head, pelvis, and feet corresponding to a heat map of where the human remains were found.

The Birka graves investigated contained 138 weapons, including 26 swords, 30 spears, 42 shields and 40 knives (Table 2). The human remains tended to be located to the right of the chamber's centre (Figure 6 and Figure 8 for the point data). Notably, the majority of swords were found to the left of centre, or on the body's right-hand side, placed next to the body whose position varied but was most probably supine, sitting, or in a semi-supine sitting position, as in grave BJ 581(Price, Reference Price, Price and Brink2008; see Figure 7). Spears were placed across the chambers, on either the right or left side, with 17 spearheads above the centre and 13 below. These concentrate in three places, towards the bottom of the chamber and to the left, lower than the body, or on either the right- or left-hand side, and above the head (if supine), suggesting that laterality was not important. The lower spears tended to be placed on the right-hand side of the chamber and the body, perhaps thrown or placed in a forward facing or defensive position. Spears thus show a degree of complexity in their placement as either mobile actors within the mortuary space, or placed alongside the deceased. Knives were located all around the chambers but with a specific concentration corresponding to the pelvis, right of centre, implying that they were part of a worn costume, perhaps on a belt, like our Early Anglo-Saxon examples. At Birka the aesthetic of the burial chamber was important and, like the Westness boat grave, the body and the sword were placed around the central axis so that, when viewing the chamber, the sword and the person are aesthetically balanced. Both sword and body were surrounded by war-gear, i.e. spears, shields, horse equipment, horses, and arrows. As suggested above, the sword does not have the same association with the laterality of the body as that shown in the Anglo-Saxon examples but, rather, it is displayed prominently and centrally, harmonizing the aesthetic of the chamber. In this way, there is a distinction between weapons and a personal sword. Interestingly, swords were sometimes the target of grave robbing, intended to subvert their role in the construction of a post-mortem personhood (Klevnäs, Reference Klevnäs2017), or within landscapes of fluctuating familial, and power dynamics (Raffield, Reference Raffield2014). The swords from the ship burials at Högom and Valsgärde were placed much more like the swords from the Early Anglo-Saxon examples: on the left, close to where adult bodies had been, as if worn or raised up the shoulder. This might imply that the Birka chamber graves were a very specific mortuary context designed to display the dead in a defined way.

Figure 6. Heat maps illustrating the most common position in a Birka chamber of weapons in relation to the body. The positions of knives are marked in purple, shields in green, spearheads in red, and swords in blue. The body location is also shown in the heat maps in black, based on the most common location of skull or teeth, pelvis, and lower legs; human skeletons were superimposed on the most common positions to allow comparison with earlier illustrations. The white cross shows the central point of the chamber and each arm of the cross is 1 m in total. The image has been superimposed on a typical Birka chamber, with its contents removed.

Figure 7. Grave BJ 581 at Birka, Sweden. An artistic reconstruction by Þórhallur Þráinsson of the female burial with weapons laid out around her body.

Figure 8. The Birka chamber layout. Top left (body parts): the red points show the position of teeth and skulls in relation to the chamber's central points; blue represents pelvises and green the lower legs. Top middle: the point data and heat map for knives, with the heat map plotted at 0.5 m. The top right shows the same data for shields, the bottom right for spears, and the bottom left for swords.

Table 2. Quantity of knives, weapons, and human remains from Birka used in this study.

Discussion

Both the literature and the archaeology suggest that swords had a specific status, and even a tendency to be anthropomorphized. It is not surprising that swords occupy a place in the poetic imagination (and perhaps broader cultural imagination), being closer to an ally than an instrument of war. The placement of the swords at the Birka, Sutton Hoo, Taplow, Högom and Valsgärde burial chambers, although different, suggests a specific, personal connection with the body. Spears, shields, and other types of war-gear (including horses, axes, seaxs, arrows, and even chain mail, which were not studied here because of their small numbers) seem to have been placed according to an expected aesthetic and without deliberate relationship to the body. The Viking flat graves in the UK incorporate the practical sword, placed as worn, or fixed to the body, inside the coffin: a hidden position that suggests the sword was understood to be a tool or weapon, rather than as the overt, symbolic display of power and identity seen in ship burials and chamber graves. Brunning's (Reference Brunning, Semple, Orsini and Mui2017) comprehensive study suggested that identifiable characteristics make a sword instantly recognisable, and old swords would convey or create histories for the observer. An association between the sword hilt and the head and shoulders of the person is notably evident from our study. When viewed as a part of a funerary performance, this placement seems to indicate that the sword is construed more as a companion than a tool, an eaxlgestealla or shoulder-companion just as in the Anglo-Saxon riddles, and to show the relationship between the deceased and their guðwine or ‘friend in war’ (Brady, Reference Brady1979: 103–04). In life, the sword is worn on display at the waist, visible and intertwined with the individual; in literature, it is characteristically called ‘on bearm’, a phrase which may either mean lying across the lap or the bosom (e.g. Beo. 40b, 1143–4, 2194b) to indicate peace. In Maxims II the poet insists, ‘sweord sceal on bearme’, (25b), i.e. ‘a sword should be in the lap’. In the grave, the sword was placed next to the corpse so that its distinctive characteristics could be displayed, placed prominently beside, and just below, the deceased's head and face, creating a proximity with the primary identity locator (Synnott, Reference Synnott1993: 22) and hence intertwining the identities of the dead and the weapon.

Despite the similar emphasis on the aesthetic and material construction of the grave, especially the focus on the head and neck area, there are still significant differences between the Viking and Anglo-Saxon examples presented. Their social contexts are dissimilar in terms of religious change, personal mobility, and the fluctuation of royal or personal power shaping the respective social and material landscapes. Importantly, our study highlights this variation within the construction of mortuary space, with weapons enmeshed with Early Anglo-Saxon bodies, the sword being central to the layout of chamber and grave, in a way that other war-gear was not. Swords were part of the mortuary drama, and in the Viking burials they take on a prominent role in the interplay between material identity and personhood, displayed alongside the body.

In the literature, the distinctive weapon is usually, but not always, a sword and this, potentially, has implications for how we read graves in which the swords are not in association with the body. This may help explain the position of the Prittlewell sword away from the body, suggesting it was placed as a sign of wealth, of war, or as an indicator of social rank not enmeshed with the individual's identity as it was in other Early Anglo-Saxon examples. The woman in grave BJ 581 at Birka has a sword close to the body, but on her left-hand side, away from the centre of the grave (Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., Reference Hedenstierna-Jonson, Kjellström, Zachrisson, Krzewińska, Sobrado and Price2017). She seems to have a stronger association with other weapons, including arrows, a sheath, and an axe, a placement that may suggest some more complex nuances in her identity (Figure 7). The location of this sword may have jarred with an observer who had witnessed weapon burials or the wearing of weapons. These types of burial narratives created tropes about their construction, and were familiar to the observers, from stories and poetry. Either BJ 581 was a burial conducted by someone unfamiliar with these tropes, or this unusual arrangement indicated something unconventional about the dead woman's identity. In this connection it is worth considering the example of Hervǫr. When claiming her father's sword, she stresses that she is his only child, presumably because a female heir was usual. On the other hand, although her father begs her not to claim the sword, he never suggests that her gender precludes her. The identity of the woman in BJ 581 might be similarly martial if unconventional. The latter seems likely since grave BJ 977 has a similar arrangement, in that the sword was positioned away from the central area of the grave and away from the body (inferred from the positions of buckles and knives). While these individuals could have been left-handed, especially BJ 977, laterality seems to have been less important in these chamber graves and so is less plausible as an explanation for the variation. It seems more likely that the variations in BJ 581 and BJ 977 indicate that martial identity in the Early Middle Ages was intricate and complex.

Conclusion

There is a clear and direct association between objects and bodies in early medieval graves. Some, like knives, were worn as clothing. Others, such as war-gear, may have signalled a social rank that was interdependent with martial status. Swords, however, seem to have been special objects, intermeshed with personhood and the performance of an elite but nuanced masculinity, just as they are in literature. This is evident in Early Anglo-Saxon graves and princely burials where the sword was embraced, placed by the head and shoulder, with the hilt accompanying the face, or positioned on top of a coffin, replicating the position of the body. In early Viking-age burials (such as the Repton grave), swords were probably seen in a more practical light, worn as objects and tools of battle. Equally, at Birka and in the North Sea boat graves, the sword and the body created an aesthetic whole, bringing a visual balance to the central area of the grave; swords were an important part of the aesthetic of commemoration, just as they were an important part of a hero's identity in the poetic corpus. A sword could be a means of transmitting identity, fulfilling obligations, or authenticating heirs. Swords are preserved in mortuary contexts but we cannot assume that all swords were buried. The literature emphasizes passing a weapon down, and there is geographic and chronological variation in sword deposition. Equally, a person might own, be given, or inherit multiple swords, which are in turn given, inherited, or placed in a grave. The inclusion of a sword in the grave was contingent on the mortuary context, inheritance, the person being buried, and the participants in the funeral. But we must also be wary. Swords placed in aesthetically awkward arrangements suggest a plurality of meaning and symbolism bound up with the sword, and its place within a grave. Moreover, burial without a sword does not mean that a person did not use one, own one, or merit one in life, a circumstance strongly supported by the many heroes who are depicted in literature as buried without their sword.