1. Introduction

Discrimination, the behavioural component of stigma [Reference Corker, Beldie, Brain, Jakovljevic, Jarema and Karamustafalioglu1], has been defined as, “the process by which a member, or members, of a socially defined group is, or are, treated differently (especially unfairly) because of his/her/their membership of that group” [Reference Krieger2]. Although discrimination is experienced by many individuals/groups in society, it is especially prevalent among people with mental health problems. Individual and cross-country research has shown for example, that as many as 50–90% of people with mental health problems may experience discrimination [Reference Corrigan, Thompson, Lambert, Sangster, Noel and Campbell3–Reference Corker, Hamilton, Henderson, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose6], and that in this population, discrimination can occur across a variety of domains such as in relation to mental and physical health care, as well as from family and friends [Reference Corker, Hamilton, Henderson, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose6, Reference Hamilton, Pinfold, Cotney, Couperthwaite, Matthews and Barret7].

The high prevalence of discrimination experienced by people with mental health problems is alarming given that it has been associated with a range of negative outcomes including reduced social capital and loneliness [Reference Webber, Corker, Hamilton, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose8, Reference Świtaj, Grygiel, Anczewska and Wciórka9], as well as impaired functioning (days out of role) and unemployment [Reference Breslau, Wong, Burnam, Cefalu, Roth and Collins10, Reference Brouwers, Mathijssen, Van Bortel, Knifton and Wahlbeck11]. There is also some evidence that discrimination may lead to reduced health service use [Reference Osumili, Henderson, Corker, Hamilton, Pinfold and Thornicroft12, Reference Clement, Williams, Farrelly, Hatch, Schauman and Jeffery13], and because of this, poorer clinical and personal recovery [Reference Mak, Chan, Wong, Lau, Tang and Tang14]. Moreover, mental health-related discrimination has also been recently linked to suicidality [Reference Farrelly, Jeffery, Rüsch, Williams, Thornicroft and Clement15]. Other research has indicated that not only the experience of discrimination but also its anticipation might be associated with negative outcomes among people with mental illness [Reference Lasalvia, Zoppei, Van Bortel, Bonetto and Cristofalo4]. It is also possible that experienced and anticipated discrimination may lead to greater internalized (mental illness) stigma [Reference Quinn, Williams and Weisz16], that has itself been linked to worse psychosocial functioning, increased symptom severity, and poorer treatment adherence in individuals with mental illness [Reference Livingston and Boyd17].

Despite an increasing focus on the association between discrimination and mental health, there are still important gaps in the research with the association remaining unexplored for many disorders. For example, until now, there has been little attention paid to the association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and discrimination. To address this omission, the current study will examine the relationship between ADHD symptoms and mental health discrimination in the English adult population. There are several reasons why such a focus is warranted. Not only is ADHD prevalent in the adult population (2.5–5%) [Reference American Psychiatric Association18–Reference Willcutt20], but it has also been associated with negative outcomes across a variety of different domains including worse physical and mental health problems/conditions and socioeconomic outcomes [Reference Das, Cherbuin, Butterworth, Anstey and Easteal21, Reference Agnew-Blais, Polanczyk, Danese, Wertz and Moffitt22], with even a low (subclinical) number of symptoms being relevant in this context [Reference Das, Cherbuin, Butterworth, Anstey and Easteal21, Reference Vogel, Ten Have, Bijlenga, de Graaf and Beekman23].

It is also possible that discrimination might be important in relation to this disorder given that several studies have highlighted that adult ADHD is associated with a high degree of stigmatization [Reference Lebowitz24, Reference Holthe and Langvik25]. Indeed, although there has been comparatively little research on stigma among adults with ADHD, an earlier study found that the mere diagnostic label ‘ADHD’ evoked negative attitudes and a lower desire for work-related/social engagement in college students [Reference Canu, Newman, Morrow and Pope26], while other research has suggested that the behaviours associated with the disorder might be important for negative attitudes [Reference Canu, Newman, Morrow and Pope26]. In particular, its ‘perceived dangerousness’ [Reference Mueller, Fuermaier, Koerts and Tucha27] has been suggested as a possible stigmatizing factor, while negative stereotypical behaviours that have been linked to the disorder include laziness and aggression [Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci and Casas-Brugué28]. It is possible that other factors might also contribute to the stigma associated with ADHD. Specifically, a lack of public knowledge about the adult disorder, and the fact that symptom presentation (predominantly inattentive or hyperactive) and severity can vary between individuals, may have also fed into concerns over the reliability of the diagnosis [Reference Mueller, Fuermaier, Koerts and Tucha27], and thus, the stigma attached to it. Nonetheless, regardless, of its specific antecedents, it has been suggested that the stigma related to ADHD might be associated with a number of detrimental outcomes including lower self-esteem and quality of life, as well as greater social isolation [Reference Holthe and Langvik25].

Given the “derision, ridicule, and stigmatization” that has been linked to ADHD [Reference Hinshaw29] and its possible negative consequences, determining the association between ADHD symptomatology and discrimination may have important clinical implications. This study thus had two main aims: (1) to explore whether ADHD symptoms are associated with a higher prevalence of perceived mental health discrimination; (2) to examine if ADHD symptoms are linked to perceived mental health discrimination after adjusting for a number of covariates that might be important for (mental health) discrimination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Study sample

Data were drawn from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, 2007 (APMS) (n = 7403). This survey was undertaken by the National Centre for Social Research and the University of Leicester between October 2006 and December 2007. An overview of the survey and its methodology was published shortly after its completion [Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins30]. A nationally representative sample of the adult population in England aged 16 and above residing in private households was obtained using multistage stratified probability sampling. The survey sampling frame was the small user Postcode Address File (PAF) while postcode sectors served as the primary sampling units (PSUs). These sectors were stratified by area and socioeconomic status. Responses were obtained from 7461 of the 13,171 eligible households with one person being recruited from within each household (to give a 57% survey response rate). The survey obtained information on a range of sociodemographic factors, health behaviours and outcomes and on the respondents’ psychopathology. A £5-10 gift voucher was given to all respondents who took part in the phase one interview as an acknowledgement of thanks for their time. To ensure that the survey was fully representative of its target population (i.e. to correct for survey non-response) sample weights were created. The Royal Free Hospital and Medical School Research Ethics Committee provided ethical approval for the study with all the respondents providing written informed consent for their participation.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Perceived mental health discrimination (dependent variable)

Information on perceived mental health discrimination (and other forms of discrimination) was obtained using computer-assisted self-interviews (CASI) as this was considered to be a sensitive topic and previous research has linked the use of CASI to a greater willingness to reveal sensitive information in surveys [Reference Tourangeau and Smith31]. Specifically, respondents were asked, “Have you been unfairly treated in the last 12 months, that is since (date), because of your mental health?” with yes and no answer options.

2.2.2 ADHD symptoms (independent variable)

Information on ADHD symptoms was collected with the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Screener. This 6-item scale, which obtains information on the past 6 month presence of inattention (4 items) and hyperactivity (2 items) symptoms, comprises part of a longer 18-item scale that assesses DSM-IV ADHD symptoms in adults. The frequency of symptoms is measured using a 5-point response scale with options running from ‘never’ – scored 0, to ‘very often’ – scored 4 to give an overall score that can range from 0 to 24, where higher scores indicate increased symptomatology. Following an earlier recommendation, scores were classified in two different ways. Firstly, scores were divided into 4 strata (Stratum I: (score 0–9); II: 10–13; III: 14–17; IV: 18–24) to assess the relation between discrimination and increasing symptomatology. Then the scores were dichotomized with respondents who scored ≥ 14 considered as having ADHD symptoms [Reference Kessler, Adler, Gruber, Sarawate, Spencer and Van Brunt32]. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the scale was 0.71. A previous scale validation study found that the specificity of this scale is high, although it has a lower degree of sensitivity [Reference Kessler, Adler, Gruber, Sarawate, Spencer and Van Brunt32].

2.2.3 Covariates

Several sociodemographic indicators were included in the analysis: sex, age, ethnicity (white British or other), educational qualification [(degree, non-degree, A-level, General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), other): yes or no], marital status (married/cohabiting or single/divorced/widowed) and equivalized income tertiles (high ≥£29826, middle £14,057-<£29826, low <£14,057). A question which inquired about 18 negative events across the life course (e.g. being expelled from school, bullied, experiencing the death of an immediate family member etc.) was used to assess stressful life events. The number of events was summed to give a continuous score that could range from 0-18. Alcohol dependence was examined with two instruments. In the first stage, the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to quantify alcohol consumption [Reference Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente and Grant33]. Respondents scoring 10 or above were subsequently assessed for alcohol dependence with the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ-C) [Reference Stockwell, Sitharthan, McGrath and Lang34] with a score of four and above being used to signify past 6-month alcohol dependence. Past year drug use was determined by asking respondents if they had consumed one or more of 13 different types of drug in the previous 12 months: cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, crack, ecstasy, heroin, acid or LSD, magic mushrooms, methadone or physeptone, tranquilizers, amyl nitrate, anabolic steroids, and glues. Those who consumed any of these drugs were coded as positive for drug use. Physical health conditions were assessed by obtaining information on 20 different health conditions diagnosed by a doctor or other health care professional that were present in the previous year (cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, migraine, cataracts/eyesight problems, ear/hearing problems, stroke, heart attack/angina, high blood pressure, bronchitis/emphysema, asthma, allergies, stomach ulcer or other digestive problems, liver problems, bowel/colon problems, bladder problems/incontinence, arthritis, bone/back/joint/muscle problems, infectious disease, and skin problems). The total number of conditions was summed for each respondent. Common mental disorders were assessed with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R) [Reference Lewis, Pelosi, Araya and Dunn35]. This measure was used to generate past week ICD-10 diagnoses of depressive episode and anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder).

2.3 Statistical analyses

The overall sample characteristics were calculated, as were differences in the sample characteristics by any mental health discrimination using Chi-square tests and student’s t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Next, the prevalence (%) of mental health discrimination across the four ADHD strata was computed. Finally, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association between ADHD symptoms (i.e. score ≥ 14 based on the ASRS) and mental health discrimination. We were unable to use the four ADHD strata for this analysis as the small numbers especially among those with high ASRS scores rendered unstable estimates. To determine the degree to which the inclusion of different covariates affects the association between ADHD symptoms and mental health discrimination, a hierarchical analysis was performed with different sets of variables being entered sequentially into the analysis. Five different models were constructed: Model 1 - adjusted for sex, age, ethnicity, education (qualification), income and marital status; Model 2 - adjusted for the variables in Model 1 and stressful life events; Model 3 - adjusted for the variables in Model 2 and alcohol dependence and drug use; Model 4 - adjusted for the variables in Model 3 and physical health conditions. Finally, the fully adjusted Model 5 adjusted for the variables in Model 4 while also including common mental disorders.

In all the models, the covariates were categorical variables with the exception of age, number of physical health conditions and stressful life events (continuous variables). As many of the participants had missing data for income (20.7%), and in an attempt to retain as many cases in the analysis as possible, a missing category was created for this variable and included in the analysis. For other variables, only ≤1.5% of the values were missing. In all analyses, Taylor linearization methods were used so that the sample weighting and the complex study design could be taken into account to enable nationally representative estimates to be produced. The results are presented in the form of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Analyses were performed with Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Details of the sample characteristics and also stratified by mental health discrimination are presented in Table 1. The analytic sample included 7274 individuals aged 18–95. The mean (SD) age of the sample was 47.5 (18.2) years old and 51.6% of the sample was female. The prevalence of ADHD symptoms and discrimination due to mental health was 5.4% and 1.1%, respectively. Compared to those who did not experience discrimination due to mental health in the past 12 months, those who did were significantly younger, had a low income, were not married/cohabiting, were more likely to be alcohol dependent and engage in drug use, and have common mental disorders, while they also had greater numbers of stressful life events and physical health conditions.

Table 1 Sample characteristics (overall and by discrimination due to mental health).

Abbreviation: SD Standard deviation.

a P-value was estimated by Chi-squared test and Student’s t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Fig. 1. Prevalence of discrimination due to mental health by severity of ADHD symptoms. Abbreviation: ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Higher scores on the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Screener represent increased ADHD symptoms. Bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

3.2 ADHD symptoms and the prevalence of mental health discrimination

The association between ADHD symptomatology and the prevalence of perceived mental health discrimination is depicted in Fig. 1 using the 4 ADHD strata. For the lowest level of symptoms (Stratum I) there was almost no mental health discrimination reported (0.3%). As the number of ADHD symptoms increased so did the prevalence of discrimination rising to 2.3% for those with 10–13 symptoms and to 5.2% for those with 14–17 symptoms. However, for those with the most severe symptoms (Stratum IV, 18–24) there was a large and statistically significant difference in the prevalence of perceived mental health discrimination (as signified by the non-overlapping confidence intervals) with 18.8% (95% CI:11.0–30.3%) reporting that they had experienced mental health discrimination in the previous 12 months.

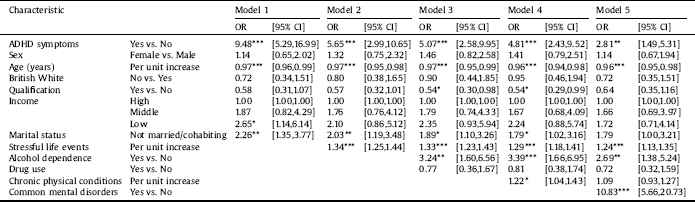

3.3 ADHD symptoms and mental health discrimination: multivariable analysis

The results from the multivariable analysis between ADHD symptoms (ASRS ≥ 14) and perceived mental health discrimination are reported in Table 2. Model 1 that adjusted for sociodemographic variables, showed that ADHD symptoms were associated with almost 10 times higher odds for mental health discrimination (OR: 9.48, 95% CI: 5.29–16.99). However, the inclusion of stressful life events in Model 2 attenuated the odds greatly (OR: 5.65, 95% CI: 2.99–10.65). The inclusion of negative health behaviours in Model 3 and physical health conditions in Model 4 also attenuated the odds but to a much smaller degree. The inclusion of common mental disorders in Model 5 also greatly reduced the odds. Indeed, an additional analysis revealed that common mental disorders were much more prevalent in those with more (ASRS ≥ 14) rather than fewer ADHD symptoms (37.5% vs. 6.2%). Nonetheless, in the fully adjusted model ADHD symptoms were still associated with almost 3 times higher odds for reporting mental health discrimination (OR: 2.81, 95% CI: 1.49–5.31).

4. Discussion

This study used data from a nationally representative sample of over 7000 household residents in England to examine the association between ADHD symptomatology and perceived mental health discrimination. Increasing ADHD symptoms were associated with a higher prevalence of mental health discrimination, but among those individuals with the highest ADHD symptom scores (ASRS 18–24), the prevalence of mental health discrimination was particularly elevated. Results from a multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that, individuals with ADHD symptoms (ASRS ≥ 14) had almost three times higher odds for experiencing mental health discrimination in the previous year even after adjustment for a variety of different covariates.

Overall, 8.1% of adults with ADHD symptoms (vs. 0.7% among those without ADHD symptoms) stated that they had experienced mental health discrimination in the previous year. Assessing this figure is complicated by the fact that previous research on mental health discrimination has focused on populations with specific mental health diagnoses where the prevalence of mental health discrimination is often very high across different life domains [Reference Corrigan, Thompson, Lambert, Sangster, Noel and Campbell3–Reference Corker, Hamilton, Henderson, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose6]. However, in an earlier large-scale general population study in the United States, although 33.5% of the respondents reported any lifetime discrimination, only 3.6% stated that physical/mental disability was the reason for their perceived (lifetime/day-to-day) discrimination [Reference Kessler, Mickelson and Williams36]. Given this, our results suggest that mental health discrimination may be significantly elevated in those with ADHD symptoms and especially among individuals with the most severe symptoms.

Table 2 Association between ADHD symptoms (ASRS ≥ 14) and discrimination due to mental health estimated by multivariable logistic regression.

Abbreviation: ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Data are odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

ADHD symptoms were defined as a score of ≥14 with the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Screener. Models are adjusted for all variables in the respective columns.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

It is uncertain what exactly underlies the higher odds for mental health discrimination among those with ADHD symptoms. Even after adjusting for factors that are common in individuals with ADHD symptoms [Reference Friedrichs, Igl, Larsson and Larsson37, Reference Stickley, Koyanagi, Takahashi, Ruchkin, Inoue and Kamio38], and that have been linked to mental health discrimination in groups with other mental health disorders, ADHD symptoms continued to be associated with significantly increased odds for past year mental health discrimination. This uncertainty is compounded by the fact that almost no individuals in the sample were taking ADHD medication (Ritalin or Straterra) [Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins30], so it is feasible to assume that the vast majority of individuals in the ADHD symptom category either did not have an ADHD diagnosis or did not know that they might have ADHD, a supposition which is supported by findings from the most recent version (2014) of the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey where very few adults who screened positive for ADHD either believed they had the disorder (3.7%) or had an ADHD diagnosis by a professional (2.3%) [Reference Brugha, Asherson, Strydom, Morgan, Christie, McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha39]. The question then becomes why would they report experiencing mental health-related discrimination?

In terms of perceived/experienced discrimination more generally, it can be hypothesized that those with the highest level of ADHD symptoms encounter this more often because they exhibit the most problematic behaviours which are met with a more negative response. The main symptoms of ADHD – inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity [Reference American Psychiatric Association18] have all been associated with a range of negative outcomes for adults across different domains including in the home and at work. For example, the reduced occupational functioning that has been observed in adults with ADHD [Reference Kirino, Imagawa, Goto and Montgomery40] might explain why ADHD carries an increased risk for unemployment [Reference de Zwaan, Gruss, Müller, Graap and Martin41]. Moreover, other research has described how individuals with ADHD may suffer from a range of deficits such as indecisiveness, procrastination, poor time management, motivational difficulties as well as being easily bored, which not only create difficulties in their own everyday lives [Reference Holthe and Langvik25] but might also affect the people around them and provoke a negative response. This might explain why there is some evidence that individuals with ADHD not only have greater interpersonal difficulties but may also perceive more negative behaviours being directed against them (e.g. receiving more criticism of their behaviour and being taken advantage of) [Reference Able, Johnston, Adler and Swindle42], which for some, might fuel feelings of being discriminated against.

It can only be speculated why many individuals, most probably without a diagnosis of ADHD, might perceive some of the life course difficulties they encounter as being examples of mental health discrimination. Given the reduction in the odds ratio when common mental disorders were included in the analysis and the fact that common mental disorders were much more prevalent among those individuals with ADHD symptoms, it is possible that some individuals may have had a comorbid/differential diagnosis or other undiagnosed disorders and it is that which they were associating with mental health discrimination. Nonetheless, by itself, this may not fully explain the association we observed, as even after controlling for common mental disorders in the analysis, the odds ratio for discrimination was still significantly elevated in those with ADHD symptoms. This highlights the need for future research to determine the specific factors that are associated with perceived mental health discrimination in adults with ADHD symptoms.

This study has several limitations that should be discussed. First, information on mental health discrimination was collected with a single dichotomous item. Hence, we had no details of the type/nature of the discrimination, who was involved, whether there was more than one episode occurring across different domains, how severe it was, or what were the consequences of the discrimination. This information would have helped us to better understand the association between ADHD symptoms and mental health discrimination and should thus be collected in future studies on this topic. Second, as the survey response rate was only 57% [Reference McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington and Jenkins30] it is possible that those with ADHD symptoms and/or more experience of mental health discrimination might have been less likely to participate, thus potentially affecting the results. An earlier study of discrimination among people using mental health services in England reported very low response rates for example [Reference Corker, Hamilton, Henderson, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose6]. Third, given the potentially sensitive nature of the topic of mental health discrimination, it is possible that this phenomenon may have been underreported, although allowing the respondents to self-complete this question may have reduced the risk of social desirability bias. Fourth, the dataset we used at the time of writing this paper was the most up-to-date publicly available version of the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Nonetheless, it was still a decade old. Further research is thus needed with more recent data to see if/how the associations we observed in this study have changed across time. Fifth, as the number of individuals in the most severe ADHD symptom category was small, there was a wide confidence interval for the discrimination point estimate. Sixth, given that we focused on ADHD symptoms, rather than diagnosed ADHD, we cannot discount the possibility that we may have been measuring symptoms of other disorders which can sometimes overlap with ADHD symptoms such as those related to bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorders [Reference Katzman, Bilkey, Chokka, Fallu and Klassen43] although we were able to control for common mental disorders in the analysis.

In conclusion, this study has shown that individuals with ADHD symptoms have a significantly increased risk of experiencing mental health discrimination. This is an important finding given that mental health discrimination has been associated with detrimental consequences in individuals with mental health disorders and therefore might also be a factor in the negative outcomes that have been noted in adults with ADHD/ADHD symptomatology. As ADHD continues to be underdiagnosed and untreated in adults [Reference Kooij, Bejerot, Blackwell, Caci and Casas-Brugué28], the results of this study highlight the importance of identifying and treating these individuals and suggest that interventions to inform the public about ADHD may be important for reducing the stigma and discrimination associated with this condition.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

AK’s work was supported by the Miguel Servet contract financed by the CP13 / 00150 project, integrated into the National R + D + I and funded by the ISCIII - General Branch Evaluation and Promotion of Health Research - and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF-FEDER). These organizations had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.