Introduction

Subsequent to experiencing a first-episode psychosis (FEP), many individuals show—regardless of whether or not the symptoms remit—remarkably stable long-term impairments in major areas of everyday life [Reference Velthorst, Fett, Reichenberg, Perlman, van Os and Bromet1,Reference Austin, Mors, Budtz-Jorgensen, Secher, Hjorthoj and Bertelsen2]. Functional impairments in various areas—including work or education, interpersonal relations, and self-care—are associated with high costs of care and decreased quality of life [Reference Germain, Kymes, Lof, Jakubowska, Francois and Weatherall3]. Consequently, these areas represent a crucial therapeutic goal for people with FEP. However, the effects of treatments on functional outcomes have been somewhat neglected compared with symptom-based outcomes [Reference Hunter and Barry4].

Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis, we have previously suggested that novel treatments targeting cognitive deficits may improve functional outcomes in FEP [Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, Gonzalez-Blanch, McGorry and Gleeson5]. However, a recent meta-analysis [Reference Halverson, Orleans-Pobee, Merritt, Sheeran, Fett and Penn6] showed only small-to-medium effect sizes for the relationship of neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes, explaining 9% of the total average variance; thus, a significant proportion of the variance remains unexplained.

To date, research carried out to identify the determinants of functioning in individuals with psychotic disorders has focused mainly on illness-related variables that are considered to have a biological origin, such as cognitive impairment or symptom severity [Reference Ventura, Hellemann, Thames, Koellner and Nuechterlein7,Reference Green, Horan and Lee8]. However, according to the biopsychosocial perspective, two other major areas have also been targeted: (a) psychological and personal resources, such as self-efficacy or coping skills and (b) social factors, such as social support or the impact of episodic stressors [Reference Yanos and Moos9], although most studies conducted to date have considered these factors separately. Consequently, a cohesive understanding of how these three major domains might interact to influence functional outcomes in these in affected individuals is lacking.

In contrast to the clinical focus on deficits, consumer perspectives have focused on the positive process of recovery from psychosis, including an emphasis upon the individual’s appraisal of personal and social resources [Reference Bellack10]. This recovery model assumes that all individuals have the capacity to improve and develop a life that is distinct from their illness. The renewed focus on social recovery is also consistent with recent psychological theories and treatments, which have proposed self-constructs and positive emotions as important targets to promote social functioning in psychosis [Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Bendall, Koval, Rice, Cagliarini and Valentine11–Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Gleeson, Bendall, Penn, Yung and Ryan14].

People with psychotic disorders diagnosis may be particularly vulnerable to social isolation (i.e., loneliness), which refers to the discrepancy between the desired and achieved number and quality of the relationships, and more likely to perceive the support received from others and the quality of this support (i.e., perceived social support) as lower than the general population [Reference Gayer-Anderson and Morgan15]. In the prevailing vulnerability-stress models describing the course of schizophrenia, social support has been postulated as a key environmental protective factor [Reference Zubin and Spring16,Reference Nuechterlein and Dawson17]. Nevertheless, the relationship between social support, loneliness, and functioning in psychotic disorders remains largely unexplored [Reference Wang, Mann, Lloyd-Evans, Ma and Johnson18,Reference Lim, Gleeson, Alvarez-Jimenez and Penn19].

According to the published literature, judgments about one’s own worth and capabilities (such as self-esteem and self-efficacy) are potential factors that may directly or indirectly influence social functioning. Indeed, several studies have found links between self-esteem (i.e., one’s sense of worth or value) and social functioning in chronic schizophrenia [Reference Bradshaw and Brekke20–Reference Brekke, Levin, Wolkon, Sobel and Slade22]. The relationship of self-esteem with psychotic phenomena is more controversial, with some studies suggesting that negative self-esteem is associated with more paranoia in response to social stressors [Reference Jongeneel, Pot-Kolder, Counotte, van der Gaag and Veling23], whereas others have found instead an association between change in self-esteem and change in negative symptoms but only during the early stages of treatment [Reference Palmier-Claus, Dunn, Drake and Lewis24]. Interestingly, the relationship between self-esteem and psychosocial functioning may be moderated by neurocognitive functioning [Reference Brekke, Kohrt and Green25]. Some studies have found that lower self-efficacy (i.e., one’s confidence in the ability to perform behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments) is associated with poorer outcomes in terms of psychosocial functioning, negative symptoms, and neurocognition [Reference Cardenas, Abel, Bowie, Tiznado, Depp and Patterson26–Reference Kurtz, Olfson and Rose29] but there is still no clear support for the mediational role of self-efficacy [Reference Hill and Startup27,Reference Vaskinn, Ventura, Andreassen, Melle and Sundet30,Reference Ventura, Subotnik, Ered, Gretchen-Doorly, Hellemann and Vaskinn31]. To the contrary, several studies have suggested that negative symptoms could mediate the impact of self-efficacy on functioning [Reference Cardenas, Abel, Bowie, Tiznado, Depp and Patterson26,Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen28,Reference Vaskinn, Ventura, Andreassen, Melle and Sundet30].

The interactions between the variables described above are likely to be complex and reciprocal. To examine the relationships between social relatedness (i.e., the need to feel connected and to perceive support from others) and self-beliefs (i.e., the subjective evaluation of our own worth and capabilities), cognition, symptoms, and functioning, we conducted a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data collected in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) carried out to improve long-term social functioning in early psychosis [Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Bendall, Koval, Rice, Cagliarini and Valentine11]. Based on findings reported in previous studies [Reference Halverson, Orleans-Pobee, Merritt, Sheeran, Fett and Penn6,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Bendall, Koval, Rice, Cagliarini and Valentine11,Reference Wang, Mann, Lloyd-Evans, Ma and Johnson18,Reference Lim, Gleeson, Alvarez-Jimenez and Penn19,Reference Cardenas, Abel, Bowie, Tiznado, Depp and Patterson26,Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen28] and on theoretical speculation, we hypothesized that (a) neurocognition will have an indirect effect on functioning through social cognition, (b) positive and negative symptoms will exert a direct effect on social functioning and will partially mediate the effect of social cognition on social functioning, and (c) social relatedness (perceived social support and loneliness) and self-beliefs (self-efficacy and self-esteem) will have a direct impact on social functioning and will mediate the effect of social cognition on social functioning in patients with FEP.

Methods

Participants

In the present study, we analyzed baseline data obtained from all participants (N = 170) in the HORYZONS trial [Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Bendall, Koval, Rice, Cagliarini and Valentine11], which we considered as a single cohort. The HORYZONS RCT was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of an online intervention designed to extend the benefits of specialized FEP services. The study inclusion criteria were (a) a first episode of a psychotic disorder or a mood disorder with psychotic features according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria, (b) age 16–27 years, inclusive, (c) ≤ 6 months of treatment with an antipsychotic medication prior to registration with Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC), and (d) remission of positive symptoms of psychosis, defined as ≥4 weeks of scores ≤3 (mild) on items P2 (conceptual disorganization) and G9 (unusual thought content) on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler32] and scores ≤4 (moderate) with no functional impairment on items P3 (hallucinatory behavior) and P1 (delusions) on the PANSS. Participants were included in the HORYZONS trial at the point of discharge from EPPIC, a specialist FEP service, Melbourne (Australia). Hence, the FEP sample included in the current study represented young people in clinical remission with a broad range of DSM-IV affective and nonaffective psychotic disorders who have received treatment in line with the mainstream model of early intervention for psychosis (including pharmacological treatment and a range of psychosocial interventions). Exclusion criteria were (a) severe intellectual disability and (b) inability to speak or read English. Additional exclusion criteria to ensure safety within the online system included a DSM-IV diagnosis of antisocial or borderline personality disorder.

All participants provided written informed consent. Ethics approval for the trial was provided by the Melbourne Health Research and Ethics Committee (No. 2013.146).

Assessments

Functioning

The Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) [Reference Nasrallah, Morosini and Gagnon33], a clinician-rated instrument, was used to evaluate overall social functioning. The PSP measures four areas of social and individual performance (self-care, socially useful activities—including work and study—personal and social relationships, and disturbing and aggressive behaviors) and provides a global score ranging from 1 to 100, with higher scores representing better functioning.

Social relatedness

The 2-Way Social Support Scale (2-Way SSS) [Reference Shakespeare-Finch and Obst34], a 21-item self-report measure, was used to measure perceptions of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental social support; higher scores are reflective of greater perceived social support. Subjective feelings of loneliness were assessed by the UCLA Loneliness Scale, version 3 (UCLA-3) [Reference Russell35], a 20-item self-report measure in which scores range from 20 (little loneliness) to 80 (great loneliness).

Self-beliefs

Self-efficacy was measured by the Mental Health Confidence Scale (MHCS) [Reference Castelein, van der Gaag, Bruggeman, van Busschbach and Wiersma36], a 16-item self-report questionnaire; the total score ranges from 16 to 96, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Self-esteem was measured by the Self-Esteem Rating Scale-Short Form (SERS-FS) [Reference Lecomte, Corbiere and Laisne37], a 20-item self-report scale comprised of two subscales to separately assess positive and negative self-esteem. For the purposes of this study, we used the total score, which was highly correlated in our study with both subscales (r > 0.85). Higher scores of the total score correspond to more positive self-esteem.

Positive and negative symptoms

Two subscales of the PANSS were used to assess negative (e.g., apathetic social withdrawal and blunted affect) and positive (e.g., hallucinatory behavior and delusions) symptoms [Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler32]. Each subscale contains seven items ranging from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Cognition

The Digit Symbol Substitution Test was used to assess neurocognitive deficits, which taps an information processing inefficiency that is a central feature of the cognitive deficit in schizophrenia and FEP [Reference Dickinson, Ramsey and Gold38,Reference Gonzalez-Blanch, Perez-Iglesias, Rodriguez-Sanchez, Pardo-Garcia, Martinez-Garcia and Vazquez-Barquero39]. This test consists of a pen-and-paper task containing rows of small blank squares, each paired with a randomly assigned number from 1 to 9. Above these rows is a printed reference key that pairs each number with a unique symbol. Using the key provided, the examinee has 120 s to fill in the corresponding symbol for each number. A higher score indicates better cognitive performance.

Two social cognition domains were assessed: (a) emotion processing and (b) theory of mind (ToM). The Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT) [Reference Bell, Bryson and Lysaker40] was used to assess emotion processing. This task consists of 21 ten-second video clips of a male actor portraying different emotions, and the participants are required to identify the emotion expressed by the actor. The total score ranges from 0 to 21, based on the total number of correctly identified emotions. The Hinting Task [Reference Corcoran, Mercer and Frith41] was used to evaluate ToM. This task consists of 10 short written passages presenting an interaction between two characters. The task is designed to measure the ability to infer true intent behind indirect speech utterances. Total score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating more appropriate responses.

Statistical analyses

As a preliminary analysis, we examined the pairwise correlation and covariance matrix for the study variables. Given that this study relies on self-reported data, we tested for possible bias due to common method variance using Harman’s single factor test [Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff42].

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the relationships among variables. The main advantage of the SEM technique is that it allows for a more precise analysis of empirical data by taking into account latent variables and complex patterns of relationships between variables [Reference Iacobucci, Saldanha and Deng43]. SEM also allows for the simultaneous use of several variables for a theoretical, unobservable construct, which ultimately leads to more valid conclusions on the construct level, helping to reduce measurement error. In the present study, social relatedness and self-beliefs were defined as latent variables. Scores on the 2-Way SSS and UCLA-3 tests were used to assess social relatedness, while scores on the MHCS and SERS-FS were used for self-beliefs. Social cognition was also defined as a latent variable, based on the Hinting Task and BLERT scores.

Social relatedness, self-beliefs, cognition (processing speed and social cognition), and (positive and negative) psychotic symptoms were included in our initial SEM model (see the initial model tested inFigure 1). The final model was obtained by removing nonsignificant effects. Since two variables may be connected in a SEM through several different pathways, direct, indirect, and total effects were estimated. Squared multiple correlations (R 2) were obtained for each endogenous variable to estimate the amount of variance explained by its predictor. Several goodness-of-fit-indices were calculated to examine the overall model fit, as follows: the absolute fit index (χ 2); the goodness of fit index (GFI); the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI); the comparative fit index (CFI); and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). GFI, TLI, and CFI values >0.90 and RMSEA values <0.08 indicated acceptable model fit, while values >0.95 (GFI, TLI, and CFI) and <0.05 (RMSEA) are indicative of excellent fit [Reference Hu and Bentler44]. All models were estimated using Mplus 7.11 [Reference Muthén and Muthén45] with a robust weighted least square (WLSMV) estimator. Previous research has shown that WLSMV results in a more accurate estimation of key model parameters than other methods [Reference Beauducel and Herzberg46,Reference Li47]. In addition, simulation studies have shown that WLSMV performs well even with sample sizes less than 200 cases [Reference Moshagen and Musch48].

Figure 1. Initial structural equation model. Rectangles represent observed measured variables. Circles represent unobserved latent variables. Values are standardized path coefficients. The squared multiple correlation value (R 2) of the Personal and Social Performance Scale indicates the amount of variance explained by its predictors. PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task; UCLA-3, UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3; MHCS, Mental Health Confidence Scale; 2-Way SSS, 2-Way Social Support Scale; SERS-FS, Self-Esteem Rating Scale-Short Form.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Of the 170 participants in the study, 90 (53%) were male. The mean age of the sample at intake was 20.9 years (SD = 2.9). The average level of education was 11.1 years (SD = 1.1). The median duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was 30 days. The baseline characteristics of the sample are summarized inTable 1. Pearson correlations between the study variables are presented in Table S1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample (N = 170).

Abbreviations: BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task; MHCS, Mental Health Confidence Scale; NOS, not otherwise specified; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale; SERS-FS, Self-Esteem Rating Scale-Short Form; UCLA-3, UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3; 2-Way SSS, 2-Way Social Support Scale.

a Median duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was 30 days.

Initial data exploration

To detect atypical cases on the analyses, z-scores were calculated for each item and checked for outliers (range, z ± 3), and the Mahalanobis distance statistical procedure (D 2) was applied. A total of 46 univariate and 7 multivariate atypical cases were identified. To determine if these atypical cases had an impact on the correlation coefficients, bivariate correlation matrices were calculated with and without the atypical cases. Finally, Cohen’s q [Reference Cohen49] was calculated to determine if there were any relevant differences between the r values. All q values were less than 0.10, indicating a very small effect size. Based on this, we decided to retain the atypical cases for the analysis.

Missing data accounted for less than 5% of the whole dataset, and these data were missing completely at random (MCAR) according to Little’s MCAR test (χ 2 = 93.587, df = 105, p = 0.780); as a result, we used listwise deletion. Asymmetry and kurtosis descriptive statistics showed that the distribution for all variables was close to normal, based on a ± 2 range of values [Reference George and Mallery50] (seeTable 1). Multivariate normality was verified using Mardia’s coefficient, which yielded a value (19.3) well below the critical value of 70 [Reference Rodríguez Ayán and Ruiz Díaz51].

SEM analyses

For the SEM analyses, we first performed Harman’s single factor test, the results of which revealed a poor fit to the data: χ 2 (44) = 143.59; GFI = .81; CFI = .77; TLI = .71; RMSEA = .13. This test indicated that common method variance was not a serious concern in our analyses. Next, we tested the hypothesized model (Figure 1), with the results indicating that the model presented acceptable fit: (χ 2 (38) = 73.25; CFI = 0.92; GFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.08, 90% confidence interval [CI] 0.06 to 0.10).

To specify the final model, we removed the paths that did not show a significant effect and analyzed the modification indices. Specifically, positive symptoms were removed from the model and a new path was specified between the negative symptoms and social relatedness. This model accounted for 45% of variance of PSP; it was more parsimonious and proved to have a better fit than the initial model (χ 2(38) = 45.48; CFI = .96; GFI = .94; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .06; 90% CI 0.02 to 0.10). Standardized path coefficients are reported inFigure 2.

Figure 2. Final structural equation model. Rectangles represent observed measured variables. Circles represent unobserved latent variables. Values are standardized path coefficients. The squared multiple correlation value (R 2) of the Personal and Social Performance Scale indicates the amount of variance explained by its predictors. PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task; UCLA-3, UCLA Loneliness Scale Version 3; 2-Way SSS, 2-Way Social Support Scale; MHCS, Mental Health Confidence Scale; SERS-FS, Self-Esteem Rating Scale-Short Form.

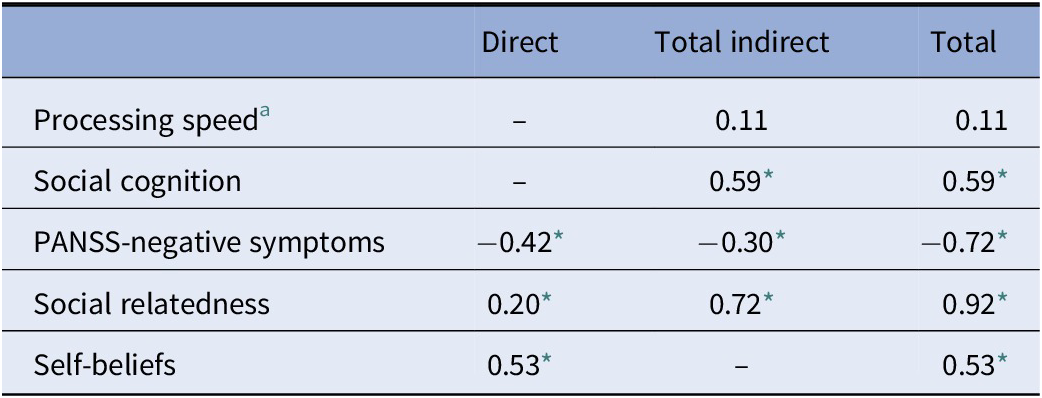

As shown inFigure 2, processing speed had a direct and significant contribution to social cognition, which in turn had a direct effect on negative symptoms and on social relatedness. Negative symptoms had a direct and significant contribution to PSP, indicating that higher levels of negative symptoms are associated with poorer functioning. Social relatedness had a significant direct on PSP and an indirect effect on PSP through self-beliefs. Finally, self-beliefs showed a direct effect on PSP. These results indicate that higher levels of social relatedness and self-beliefs were associated with better social functioning (see estimates of direct and indirect effects for each variable inTable 2).

Table 2. Estimates of direct, indirect, and total effects of illness-related and social relatedness and self-beliefs on PSP in the final model.

Abbreviations: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance Scale.

a Measured by a Digit Symbol task.

* p < 0.001.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the role of social relatedness and self-beliefs in explaining social functioning in a sample of individuals with FEP. The SEM approach was used to conduct the analysis, as it takes into account latent variables and complex patterns of relationships between variables. Our findings indicated that social relatedness and self-beliefs, together with social cognition and negative symptoms, explained 45% of the variance in social functioning.

Most previous research has linked, in separate studies, specific variables to diverse aspects of social functioning. For example, self-efficacy was found to be an independent predictor of functioning in FEP [Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen28] and, in other models, the effects of self-efficacy on functioning were mediated through negative symptoms [Reference Vaskinn, Ventura, Andreassen, Melle and Sundet30,Reference Ventura, Subotnik, Ered, Gretchen-Doorly, Hellemann and Vaskinn31]. In our study, latent variables reflecting social relatedness and self-beliefs were linked to social functioning. Overall, this finding is consistent with research showing that functioning does not depend only on illness-related factors [Reference Galderisi, Rossi, Rocca, Bertolino, Mucci and Bucci52]. There is a large body of evidence indicating that perceived personal resources are linked to performance attainments [Reference Bandura and Locke53], and some studies have confirmed this association in individuals with FEP [Reference Beck, Himelstein, Bredemeier, Silverstein and Grant12,Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen28].

Our final model showed a direct effect of social relatedness on functioning and an indirect effect through self-beliefs. Furthermore, a path was specified between negative symptoms and social relatedness, indicating that at least part of the well-recognized effect of negative symptoms on social functioning is due to its influence on loneliness and perceived lack of social support. This is consistent with data from meta-analyses showing that there is a significant relationship between loneliness and psychotic symptoms in people with psychosis [Reference Michalska da Rocha, Rhodes, Vasilopoulou and Hutton54]. Specifically, higher levels of negative symptoms have been associated with a lack of friendships in individuals with psychotic disorders [Reference Giacco, McCabe, Kallert, Hansson, Fiorillo and Priebe55], and low satisfaction with social support and loneliness have been associated with more negative symptoms [Reference Sundermann, Onwumere, Kane, Morgan and Kuipers56]. The association between social relatedness and negative symptoms could be partly due to social anhedonia, a type of social withdrawal driven by the lack of perceived reward from social situations. However, the so-called “anhedonia paradox” posits that individuals with schizophrenia spend a smaller proportion of their time in social situations and other pleasurable activities despite their apparently normal hedonic responses [Reference Cohen and Minor57]. A possible explanation for this is the dissociation of anticipatory (the experience of pleasure related to future activities) versus consummatory (in-the-moment pleasure experience) hedonic systems. It has been postulated that the negative symptoms could be largely related to deficits in anticipatory anhedonia. Interestingly, social functioning has been related to individuals’ reports of anticipatory but not consummatory pleasure [Reference Gard, Kring, Gard, Horan and Green58].

In line with previous research [Reference Hunter and Barry4,Reference Ho, Nopoulos, Flaum, Arndt and Andreasen59–Reference Verma, Subramaniam, Abdin, Poon and Chong63], negative symptoms in our model had a strong and direct relationship with functioning and also influenced individuals’ social relatedness. Contrary to our hypothesis, however, positive symptoms dropped-out of the final model. A possible explanation for this is that most participants in this study were in remission of positive symptoms. Besides this, negative symptoms have been shown to be more strongly related to functioning than any of the other symptoms [Reference Ventura, Hellemann, Thames, Koellner and Nuechterlein7,Reference Rabinowitz, Levine, Garibaldi, Bugarski-Kirola, Berardo and Kapur62,Reference Lin, Huang, Chang, Chen, Lin and Tsai64].

The relationship between neurocognition (as measured by a processing speed task) and functioning was mediated by social cognition, which is in line with previous studies [Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder65]. However, at odds with most previous research [Reference Halverson, Orleans-Pobee, Merritt, Sheeran, Fett and Penn6], our model did not show a direct path between social cognition and functioning. Instead, the influence of social cognition on functioning was mediated by social relatedness and negative symptoms. Interestingly, in Lin and colleagues’ study, [Reference Lin, Huang, Chang, Chen, Lin and Tsai64] the direct path from cognitive function (a latent variable which included neurocognition and social cognition variables) to functional outcome was no longer significant when symptoms were entered into the model. A possible explanation is that the unique contribution of social cognition to social functioning depends on the domains of social cognition assessed [Reference Halverson, Orleans-Pobee, Merritt, Sheeran, Fett and Penn6] as well as the constructs examined in the model. As has been suggested by Beck et al. [Reference Beck, Himelstein, Bredemeier, Silverstein and Grant12], the fact that in most previous studies, psychological and social factors have typically been viewed as confounds rather than as meaningful sources of variance might have led to an overestimation of the magnitude of the effect of neurocognition and social cognition on functioning. This is consistent with earlier research that overestimated the effect of neurocognition on functioning because the role of social cognition was not taken into account (e.g., [Reference Schmidt, Mueller and Roder65]).

It is worth noting that the proportion of the variance of social functioning explained by our model is greater than that found in other cross-sectional studies using path analysis or SEM with a more restricted set of constructs related to social support and self-beliefs (variance accounted for ranges from 5 to 25%) [Reference Brekke, Kay, Lee and Green66–Reference Couture, Granholm and Fish69] and more similar to other studies that have included self-efficacy (31%) [Reference Chang, Kwong, Hui, Chan, Lee and Chen28] or a comprehensive set of illness-related variables, personal resources, and context-related factors (54%) [Reference Galderisi, Rossi, Rocca, Bertolino, Mucci and Bucci52].

The direct explanatory power of social relatedness and self-beliefs highlights the importance that these experiences might play in the theoretical explanation of the relationship of negative symptoms and cognition with social functioning in FEP, which is crucial for enhancing the effects of early interventions in this population. In practical terms, there is a need to address these subjective domains and not just illness-related factors such as symptoms or cognitive functioning. Furthermore, given the central role of social relatedness, it is possible that the functional benefits of social cognition interventions can be explained best by the impact of these domains on the individual’s appraisals of social relatedness. On the other hand, developing psychosocial interventions targeting personal competence and connectedness with others might be the best way to augment social functioning in young people at the early stages of a psychotic disorder [Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Bendall, Koval, Rice, Cagliarini and Valentine11,Reference Browne, Estroff, Ludwig, Merritt, Meyer-Kalos and Mueser13,Reference Lee and Goldstein70,Reference Wu, Outley, Matarrita-Cascante and Murphrey71].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we used a cross-sectional design, thus causality can only be inferred, and we cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causation as an explanation of our findings. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the directionality of the investigated variables. Second, the sample size was only moderate for conducting a SEM analysis, which might have resulted in inaccurate parameter estimates and model fit statistics. However, to ameliorate this limitation, we tested the validity of the model with fit indices which are less affected by sample size (such as CFI), and we used WLSMV, which has proven to perform well with sample sizes with less than 200 cases [Reference Moshagen and Musch48]. Third, this study involves a secondary analysis of an RCT, and data were not collected to test our hypothesis; other variables potentially related to social functioning (for example, personality, motivation, childhood trauma, or socioeconomic conditions) were not included in this study. Fourth, this study uses an FEP sample with a broad range of diagnoses; given the sample size, the model could not be tested separately for affective and nonaffective psychoses. Moreover, the relevance of illness-related factors can arguably change with the progression of the illness- or treatment-related processes. However, contrary to the earliest conceptions of schizophrenia, recent meta-analytic data suggest that negative symptoms are likely to improve over time [Reference Savill, Banks, Khanom and Priebe72] and cognitive deficits in first-episode samples are comparable to those in later phases of the illness [Reference Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone and Seidman73]. Affective psychotic disorders, however, might exhibit a different longitudinal course [Reference Lewandowski, Cohen and Ongur74]. Hence, our findings could not be generalized to other phases of illness. Fifth, DUP, a predictor of long-term functional recovery [Reference Santesteban-Echarri, Paino, Rice, Gonzalez-Blanch, McGorry and Gleeson5], was comparatively briefer in our cohort than in the general FEP population. Finally, we used a global measure of social functioning (PSP total score), which might not be sufficiently precise to detect more specific relationships between variables. Nonetheless, the PSP has been shown to have high reliability and validity in both acutely ill [Reference Patrick, Burns, Morosini, Rothman, Gagnon and Wild75] and stable [Reference Nasrallah, Morosini and Gagnon33] mental health patients. In addition, we used a single measure of processing speed (a Digit Symbol task) instead of a more comprehensive set of measures to assess more varied and specific neurocognitive domains. Although Digit Symbol tasks have shown to be particularly good in capturing the generalized dysfunction that may underlie widespread cognitive failures in psychotic disorders [Reference Gonzalez-Blanch, Perez-Iglesias, Rodriguez-Sanchez, Pardo-Garcia, Martinez-Garcia and Vazquez-Barquero39] and have shown the largest association with social functioning [Reference Dickinson and Coursey76], it is plausible that other measures of specific cognitive domains could yield different results.

Conclusions

This study underscores that self-beliefs and the perceptions of social connections with others in young people with FEP are related to their social functioning. Psychological therapies focused on developing positive ways of self-relating and enhancing social connections may offer a fruitful approach to improve functional outcomes in young people with psychosis. In addition, the findings of this study also suggest that both individuals’ subjective experiences and illness-related factors play complementary roles in influencing functional outcomes in FEP, and, therefore, importantly, the lack of acknowledgment of social relatedness and self-beliefs in the explanatory models of social functioning in FEP can lead to an overestimation of the effect of the illness-related factors.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.90.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request, Prof. Mario Alvarez-Jimenez (mario.alvarez@orygen.org.au).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Orygen Youth Advisory Council and Orygen Youth Research Council for their input into the development of Horyzons. The authors also wish to thank the inspiring and generous young people who took part in the study.

Financial Support

The HORYZONS trial was supported by the Mental Illness Research Fund from the State Government of Victoria. C.G-B was supported by a Research Intensification Grant (INT/A19/02) from the IDIVAL. S.B. was supported by the McCusker Charitable Foundation (grant number N/A). S.O.S. was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1144563). M.A-J. was supported by a Career Development Fellowship (APP1082934) and by an Investigator Grant (APP1177235) from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.