Is geographical isolation related to development outcomes such as financial development? To the best of our knowledge, the answer to this question is missing in empirical literature. Various aspects of financial development to explain its relative presence or absence have been explored over the past decades, notably: theories related to credit information and power (Stieglitz and Weiss Reference Stiglitz and Weiss1981; Aghion and Bolton Reference Aghion and Bolton1992; Djankov et al. Reference Djankov, Mcliesh and Shleifer2007; Tchamyou and Asongu Reference Tchamyou and Asongu2017); theory of law and finance (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Florencio, Shleifer and Vishny1997; Beck et al. Reference Beck, DEMIRGÜÇ-Kunt and Levine2003); culture (Stulz and Williamson Reference Stulz and Williamson2003; Kodila-Tedika and Asongu Reference Kodila-Tedika and Asongu2015a); abuse of market power and competition in the banking sector (Coccorese and Pellecchia Reference Coccorese and Pellecchia2010; Coccorese Reference Coccorese2012); globalisation (Asongu Reference Asongu2014; Asongu and De Moor Reference Asongu and De Moor2017); remittances (Osabuohien and Efobi Reference Osabuohien and Efobi2013; Efobi et al. Reference Efobi, Osabuohien and Stephen2015); endowment theory (Beck et al. Reference Beck, DEMIRGÜÇ-Kunt and Levine2003); the role of the state (Rajan and Zingale 2003; Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Cavallo and Scartascini2012; Ang Reference Ang2013a); genetic distance (Ang and Kumar Reference Ang and Kumar2014); macro-finance (Rajan and Zingales Reference Rajan and Zingales1998; Baltagi et al. Reference Baltagi, Demetriades and Law2009); social capital (Guiso et al. Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004) and human capital (Kodila-Tedika and Asongu Reference Kodila-Tedika and Asongu2015b).

The study closest to the present inquiry is Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010), which has examined how cross-country differences in the degree of prehistoric geographical isolation affect the contemporary development process with respect to income per capita. The authors have also been motivated by the absence of studies that examine the relationship between prehistoric isolation and contemporary development outcomes. Existing studies on comparative development have emphasised a plethora of ultimate and proximate characteristics underpinning some of the substantial disparities in standards of living across the globe. The relevance of cultural, institutional, geographical and religious fractionalisation, as well as linguistic, ethnic, globalisation and colonisation features, have motivated the debate on the timing of differential economic growth from stagnation to modern growth over the past 200 years. According to Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010), whereas the underlying factors have been investigated from the perspective of contemporary effects, less attention has been paid to prehistoric characteristics that have affected contemporary development and cross-country differences in economic growth.

The motivation for assessing the nexus between geographical isolation and economic development builds on the intuition that globalisation has been documented to affect the development process, through inter alia: trade (Musila and Sigué Reference Musila and Sigué2010); capital flows (Price and Elu Reference Price and Elu2014; Motelle and Biekpe Reference Motelle and Biekpe2015); foreign aid (Kayizzi-Mugerwa Reference Kayizzi-Mugerwa2001; Obeng-Odoom Reference Obeng-Odoom2013) and technological diffusion (Tchamyou Reference Tchamyou2016). According to Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010), the reduced ability of societies that are geographically isolated to gain from progress in global technological frontiers could have compelled independent advancements in technological progress, therefore inducing a fundamental cultural setting that is favourable to innovation and development. Furthermore, geographically isolated societies might have benefited from the diminished threat of predation, which logically fostered efficient allocation of resources towards development outcomes and protected property rights, ultimately contributing to the setting of fundamental cultural values that are beneficial to economic development.

In the light of the fact that geographical isolation promoted a fundamental and persistent cultural environment that enhanced development, it is plausible to infer that prehistoric geographical isolation has played a significant role in the development process, hence, influencing contemporary development across the world.

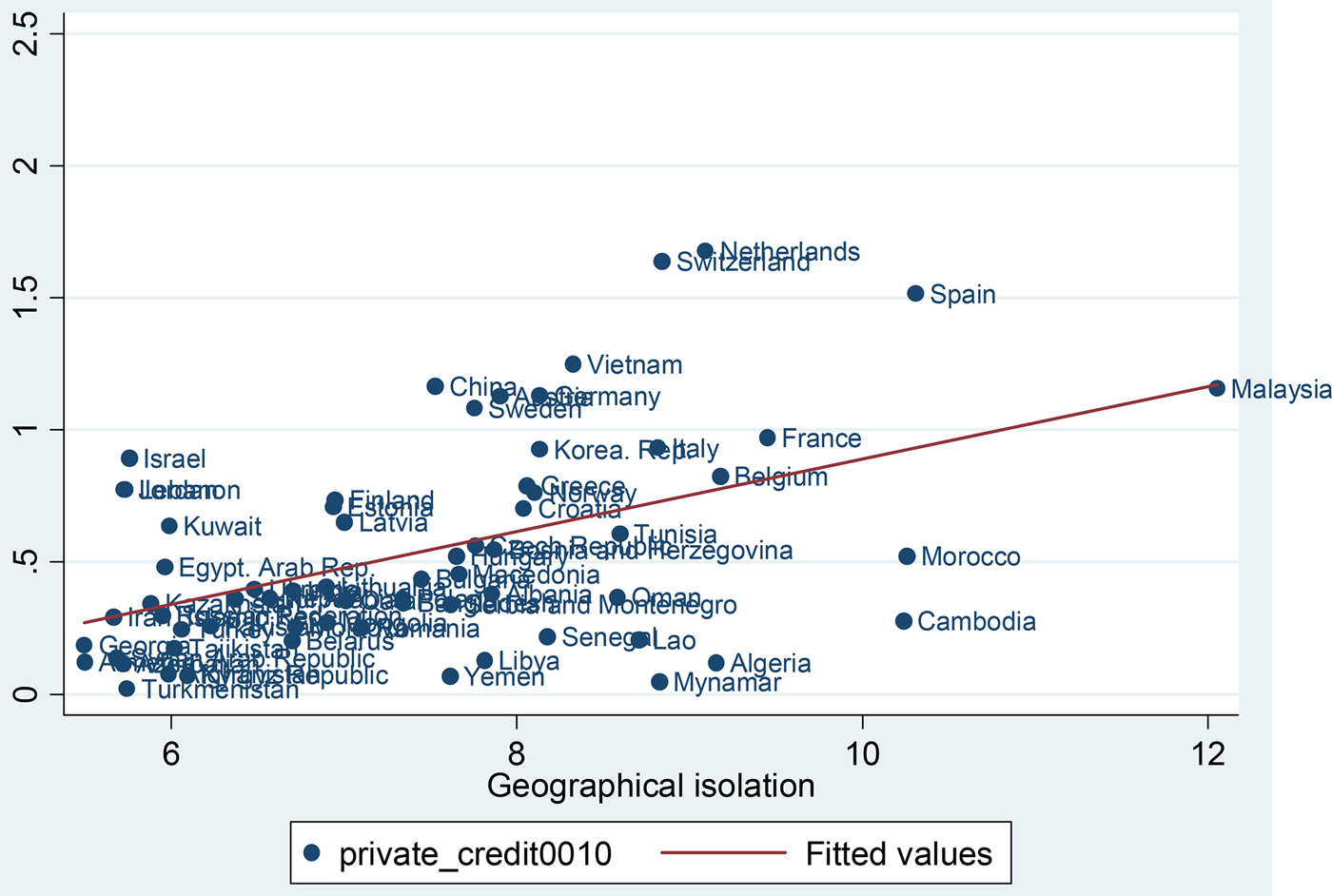

This study exploits prehistoric cross-country differences in geographical isolation in order to assess its effect on financial development across the globe. Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010) consider prehistoric geographical isolation prior to the advent of airborne and sea-faring technologies of transportation as proximate and ultimate causes underlying some of the cross-country differences in living standards across the globe. We find that prehistoric geographical isolation has had a significant positive relationship with the process of development because it has contributed to contemporary cross-country differences in financial development. The relationship is robust to alternative samples, different estimation techniques, outliers and varying conditioning information sets. The relationship between isolation and financial development is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Geographical isolation and financial development (2000–10)Footnote 1

The rest of the study is structured as follows. Section i discusses the theoretical underpinnings of the relationship between openness and development. The data and methodology are outlined in Section ii. Section iii presents empirical results, while Section iv covers robustness assessments. Concluding implications and future research directions are provided in Section v.

I

There are two principal theoretical bases for the relationship between openness and development, notably: the neoliberal view and the hegemony perspective (see Tsai Reference Tsai2006; Asongu Reference Asongu2013). First, the neoliberal strand of openness argues that openness is an instrument of ‘creative destruction’ in the perspective that technological innovation, global trade and cross-border investment enhance efficiency in production and engender substantial progress in spite of job substitution and falling wages for workers that are unskilled. According to the narrative, the drawbacks of openness are assuaged by requesting workers that are unskilled to improve on their know-how in order to gain from the positive externalities of increasing openness. According to Grennes (Reference Grennes2003), such benefits can be rewarding to the population if the labour market is influenced by ‘supply and demand’.

Second, with regard to the hegemonic strand, policies favouring global openness are hidden projects that are designed to create a new world order which will be under the control of global financial institutions and developed countries. This school of thought maintains that openness encourages the accumulation of capital, growing inequality and extension of rewards of trade in goods and services to trade in financial assets. Proponents of this stream predict ‘a world-wide crisis of living standards for labor’, granting that the capital accumulation process has been borne by the working class because ‘technological change and economic reconversion endemic to capitalist development has generated an enormous growing pool of surplus labor, an industrial reserve army with incomes at or below the level of subsistence’ (Petras and Veltmeyer Reference Petras and Veltmeyer2001, p. 24).

Another dimension of the hegemonic view maintains that production modes of neoliberal policies are connected to a process of dynamic production which undermines redistribution channels that are consistent with Keynesian social democracy. According to some narratives in this strand, global openness favours the quest for private gains to the detriment of more ethical values like inclusive development (Smar Reference Smart2003) and environmental protection (Obeng-Odoom Reference Obeng-Odoom2015). Furthermore, the redistribution process of benefits from openness is skewed in favour of the faction of the population that is already in privileged socio-economic positions (Scholte Reference Scholte2000). Though from a less radical perspective, Scholte's position is shared by Sirgy et al. (Reference Sirgy, Lee, Miller and Littlefield2004).

The decision on whether a country should adopt openness policies in view of stimulating domestic financial development remains open to debate in the literature (Asongu and De Moor Reference Asongu and De Moor2017). Asongu (Reference Asongu2014) provides two perspectives on the importance of openness in financial development.

The first perspective on allocation efficiency, which is based on theoretical underpinnings of the neoclassical growth model from Solow (Reference Solow1956), considers that openness eases the efficient allocation of resources at the international level. Those that hold this view maintain that capital resources (which in part simulate financial development) will flow from countries in which capital is abundant to countries in which capital is scarce. In capital-scarce countries, positive rewards include externalities that are essential to raise standards of living, among others: increased investment, reduced capital cost and growth that is pro-poor (see Fischer Reference Fischer and Fischer1998; Obstfeld Reference Obstfeld1998; Rogoff Reference Rogoff1999; Summers Reference Summers2000; Batuo and Asongu Reference Batuo and Asongu2015). Over the past decades, many countries have justified the need for more openness with such potential rewards.

Conversely, another strand of the literature maintains that the arguments of allocation efficiency in resources are a fanciful attempt to extend gains from international trade in commodities to international trade in assets. With regard to this sceptical view, the rewards of allocation efficiency are feasible if and only if the transfer of international resources is not characterised by volatilities. Hence, as argued in recent literature (Rodrik Reference Rodrik and Fischer1998; Rodrik and Subramanian Reference Rodrik and Subramanian2009; Batuo and Asongu Reference Batuo and Asongu2015), in the light of volatilities that have been experienced by some countries, the theoretical foundations of allocation efficiency may not reflect practical reality. In this light, the pessimistic opinions are best articulated by Rodrik (Reference Rodrik and Fischer1998) and Rodrik and Subramanian (Reference Rodrik and Subramanian2009), with respective titles like ‘Who Needs Capital-Account Convertibility?’ and ‘Why Did Financial Globalization Disappoint?’ For instance, Rodrik (Reference Rodrik and Fischer1998) maintains that there is no nexus between openness and the level of ‘growth and investment’ in developing nations. He articulates that whereas it is difficult to establish the benefits of capital account openness, the costs of financial openness are growingly apparent through financial crises that are increasing in terms of frequency and magnitude. Rodrik and Subramanian (Reference Rodrik and Subramanian2009) have established that the subprime mortgage crisis, which resulted in the global financial crisis, has raised doubts about the net development benefits of growing financial openness.

Dornbusch (Reference Dornbusch1996) considered capital controls as ‘an idea whose time had past’ and reaffirmed his position two years later that ‘the correct answer to the question of capital mobility is that it ought to be unrestricted’ (Dornbusch Reference DORNBUSCH and Fischer1998, p. 20), while Fischer (Reference Fischer and Fischer1998) recommended orderly openness. The perspective of Fischer (Reference Fischer and Fischer1998) is shared by Henry (Reference HENRY2007) and Kose et al. (Reference Kose, Prasad and Taylor2011), with the latter perspective building on Kose et al. (Reference Kose, Prasad, Rogoff and Wei2006) who have surveyed the literature and concluded that the indirect benefits are more relevant than traditional financial mechanisms articulated in previous studies. This has led to a recent stream of scholarly debates on China being de jure closed and de facto open (Prasad and Wei Reference Prasad, WeI. and Edwards2007; Aizenman and Glick Reference Aizenman and Glick2009; Shah and Patnaik Reference Shah and Patnaik2009).Footnote 2 Moreover, according to recent literature, the gains in financial openness are increasingly blurred because financial openness is associated with, inter alia, growing external debt that is fuelling inequality (Azzimonti et al. Reference Azzimonti, De Francisco and Quadrini2014) and worsening business cycles (Leung Reference Leung2003) on the one hand and decreasing productivity and efficiency on the other hand (Mulwa et al. Reference Mulwa, Emrouznejad and Murithi2009).

The positioning of this inquiry steers clear of the above in that it assesses the role of geographical isolation in financial development. In other words, we examine whether prehistoric geographical isolation has been beneficial to financial development.

II

We examine a sample of 66 countries with average contemporary data for the period 2000–10 and prehistoric data on geographical isolation. The financial development dependent variable is private domestic credit as a percentage of GDP.

The independent variable of interest is the index of isolation from Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010). According to the authors, this is a new indicator of geographical isolation that was prevalent in the distant past and it represents the average time needed to travel from a country's capital to each kilometre square of land on earth, accounting for routes that can minimise the time to travel in the absence of airborne and maritime transportation technologies. The isolation index developed by the authors enables the exploitation of exogenous variation in extent of isolation, before the advent of underlying transportation technologies.

In the light of the above, for any given country, the isolation index represents the unweighted mean of the time that is needed to reach the capital of a country along paths that are cost minimising. While employing an alternative index of isolation that is limited to the average time needed to travel from the capital of one country to the capital of another does not generally change the main empirical results from a qualitative standpoint, the adopted index is better because it accounts for the potential endogeneity that arises when the locational choice associated with the development of major urban centres was not parallel to main cities’ spatial distribution. Hence, the isolation index employed within the framework of this study enables the exploitation of exogenous differences in the level of isolation before the advent of airborne transportation and sea-faring. This articulation is meant to identify the effect of geographical isolation in the prehistoric era on the path of economic development via history (Ashraf et al. Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010).

Following Ang and Kumar (Reference Ang and Kumar2014) and Kodila-Tedika and Asongu (Reference Kodila-Tedika and Asongu2015b) in recent financial development literature, we control for: aerial isolation, financial openness, trade openness, interaction between financial openness and trade openness, creditors’ rights, religions (Protestants, Muslims and Catholics), legal origins (French, British, Scandinavian and German), tropics and latitude. The definitions of the variables, summary statistics and correlation matrix are provided in the Appendix. We discuss the expected signs concurrently with the estimation of results.

Consistent with the above and the geographical isolation (Ashraf et al. Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010) literature, we employ Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) in order to assess the nexus between geographical isolation and financial development. The specification is presented in equation (1).

Where: FD i (GI i ) represents financial development (geographical isolation) indicator for country i, α1 is a constant, X is the vector of control variables, and ε the error term. X consists of: aerial isolation, trade openness, creditors’ rights protection, financial openness, legal origins, tropics and latitude.

III

Table 1 presents findings based on regressions in equation (1). The first column which shows univariate regressions establishes a positive correlation between historical geographical isolation and financial development; that is, a one standard deviation increase in the average time required to walk to a country's capital from all locations in the Old World is associated with 0.48 percentage points increase in financial development and significant at 1 per cent. In fact, this indicates that isolation is positively correlated with private sector credit. Columns 2 to 8 examine the nexus conditional on other covariates (control variables). The ordering of the specification is in line with recent financial development literature (Ang and Kumar Reference Ang and Kumar2014; Kodila-Tedika and Asongu Reference Asongu2015b). The positive magnitude varies between 0.086 (column 7) and 0.159 (column 3). The coefficient varies from 22.7 per cent in univariate regressions (column 2) to 66.2 per cent (columns 7 and 8). This consistent increasing magnitude in the adjustment coefficient is in line with the intuition because the explanatory power of a model should increase with improvements in the conditioning information set.

Table 1. OLS for the relationship between isolation and financial development

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively.

Most of the significant control variables have the expected signs. These include: (i) the protection of creditor rights has been documented to be linked to higher levels of financial development (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Florencio, Shleifer and Vishny1998); (ii) given that financial openness is connected with availability of more external flows, it should also be linked with more possibilities for private domestic credit; (iii) countries with French legal traditions are associated with less financial development (La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes and Shleifer2008; Asongu Reference Asongu2012a Reference Asongub); (iv) compared to Muslim and Catholic nations, countries which are dominated by ‘Protestants’ are more likely to enjoy higher levels of financial development. The edge of the Protestant culture typically builds on Weber's (Reference Weber, Baehr and Wells1930) ‘Protestant Ethic Thesis’. According to Weber, the northern region of Europe experienced more advanced capitalism because a substantial part of the population was motivated by the Protestant ethic to set up its own enterprises.Footnote 3 It is in this light that the region adopted a culture of: (i) engaging in trade and investment activities for the accumulation of wealth and (ii) working in a secular world. The ‘Protestant Ethic Thesis’ also elicits the negative nexus between the dependent variable and the ‘Muslim dummy’. This is in accordance with the evidence that Muslim nations are less democratic (Fish Reference Fish2002, p. 4).

IV

In this section, we perform several robustness checks using the specification in column 7 of Table 1 as baseline. These checks include: controlling for influential observations; using alternative sample periods and varying the conditioning information set.

In order to further improve the quality of estimations, we control for influential observations following M-estimators of Huber (Reference Huber1973) by employing iteratively weighted least squares (IWLS). As documented by Midi and Talib (Reference Midi and Talib2008), compared to the approach by OLS, the IWLS technique has the advantage of simultaneously controlling for problems arising from the presence of outliers and/or heteroscedasticity. The results in Table 2 in terms of signs and significance remain consistent with those established in Table 1. Moreover, the estimate corresponding to aerial isolation is now significant. Next, in column 3, we perform the sensitivity check on baseline estimates with control variables, after dropping the smallest observations. The corresponding findings are consistent with baseline results. Lastly, following Nunn and Puga (Reference Nunn and Puga2012, pp. 25–6) and Kodila-Tedika and Asongu (Reference Asongu2015b), we adopt a systematic approach of eliminating influential observations for which DFBETA| >2/

![]() $ \sqrt {\rm N} $

, where N is the number of observations. Corresponding findings in column 4 of Table 2 are consistent with baseline specifications.Footnote

4

$ \sqrt {\rm N} $

, where N is the number of observations. Corresponding findings in column 4 of Table 2 are consistent with baseline specifications.Footnote

4

Table 2. Controlling for outliers

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

In Table 3, we employ the alternative sample periods for further robustness purposes. These include: 1980–2010; 1985–2010; 1990–2010; and 1995–2010. The resulting findings confirm the direction of the underlying correlation and further reveal that irrespective of periodicities, the link between financial development and geographical isolation is positive. Moreover, the coefficient on geographical isolation increased slightly from 1980–2010 to 1995–2010. This incremental effect suggests that the nexus is more apparent in the contemporary era.

Table 3. Estimates based on alternative sample periods

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

In Table 4, we control for other impacts to further assess the robustness of our baseline findings. We augment our baseline model with other controls such as: ethnic fragmentation; institutions; social capital; continents and income. The definitions of these variables and corresponding sources are disclosed in the Appendix. From a more general perspective, the new variables account for the unobserved heterogeneity that was not included in baseline regressions. The baseline results are confirmed in terms of significance and sign, though the correlation is lower with the addition of income, institutions and ethnic fractionalisation and higher when social capital is added. The additional control variables display anticipated signs because income levels, institutions and social capital are positively related to financial development whereas ethnic fractionalisation has the opposite effect, as demonstrated in Girma and Shortland (Reference Girma and Shortland2008), Ang and Kumar (Reference Ang and Kumar2014) and Guiso et al. (Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004).

Table 4. Controlling for other effects

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

We briefly document the selection of additional covariates. Guiso et al. (Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004) have articulated that social capital has been instrumental in improving financial development. The positive role of institutions has also been documented by Girma and Shortland (Reference Girma and Shortland2008). Beck et al. (Reference Beck, DEMIRGÜÇ-Kunt and Levine2003) have demonstrated that ethnic diversity impairs financial development. Asongu (Reference Asongu2012a) and Ang and Kumar (Reference Ang and Kumar2014) have shown that wealthy countries are associated with higher levels of financial development.

We perform further robustness checks by using alternative financial development indicators. The scope of this extension is not limited to the financial intermediary sector (or short term finance) but is extended to stock markets (or long-term finance). Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 respectively show results corresponding to domestic credit, stock market capitalisation, stock-market-value traded and stock market turnover ratio. The findings are not consistent with those established earlier because financial intermediary development is more connected to geographical isolation compared to stock market development, which is more related to aerial isolation.

Table 5. Using domestic credit as a measure of financial development

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

Table 6. Using stock market capitalisation as a measure of financial development

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

Table 7. Using stock market value traded as a measure of financial development

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

Table 8. Using stock market turnover ratio as a measure of financial development

Notes: *; **; *** denote significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1% respectively. Control variables in the last column of Table 1 are included.

The findings established broadly confirm the strand of literature questioning the relevance of openness in financial intermediary development by means of allocation efficiency and international risk-sharing. As discussed in the theoretical underpinnings of the study, there is a strand of literature maintaining that openness results in global financial instability (Stiglitz Reference Stiglitz2000; Rodrik Reference Rodrik and Fischer1998; Bhagwati Reference Bhagwati1998), while another strand maintains that growing financial integration has improved economic stability in developed countries while enabling low-income countries to make the transition to middle-income countries (Fischer Reference Fischer and Fischer1998; Summers Reference Summers2000).

The findings can also be viewed to be in accordance with recent development literature that holds that openness has not resulted in more investment in developing countries and stability in developed countries (see Rodrik and Subramanian Reference Rodrik and Subramanian2009). This is essentially because, according to the narrative, countries that have enjoyed more economic development in recent decades have surprisingly been those that have been least opened. For instance, Asongu (Reference Asongu2014) has argued that contemporary evidence for the development rewards from openness remain unpersuasive, indirect and speculative. Moreover, the findings also support the view that more resources from economic openness are not necessarily better.

As long as the world economy remains politically divided among different sovereign and regulatory authorities, global finance is condemned to suffer from deformation far worse than those of domestic finance. Depending on the context and country, the appropriate role of policy will be as often to stem the tide of capital flows as to encourage them. Policymakers who view their challenges exclusively from the latter perspective will get it badly wrong. (Rodrik and Subramanian Reference Rodrik and Subramanian2009, pp. 16–17)

V

There is a recent strand of literature documenting evidence that prehistoric geographical isolation had a fundamental cultural impact on the development process that has contributed to contemporary variations in economic development. This study has expanded this strand of literature by assessing whether prehistoric geographical isolation is related to development outcomes such as financial development. We have exploited prehistoric cross-country differences in geographical isolation in order to assess its effect on financial development across the globe. Prehistoric geographical isolation is defined as prior to the advent of airborne and sea-faring technologies of transportation. We find that prehistoric geographical isolation has been beneficial to development because it has contributed to contemporary cross-country differences in financial intermediary development. The relationship is robust to alternative samples, different estimation techniques, outliers and varying conditioning information sets. The findings broadly confirm the positive relationship between geographical isolation and GDP per capita established by Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010). Unfortunately, the established positive relationship between geographical isolation and financial intermediary development does not significantly extend to stock market development.

Ashraf et al. (Reference Ashraf, Özak and Galor2010) and Özak (Reference Özak2016) have shown that isolation may affect development through various cultural or institutional channels; one such channel may thus be financial development as established in this study, given the consensus on the positive relationship between financial development and economic development (Nyasha and Odhiambo Reference Nyasha and Odhiambo2015a, Reference Nyasha and Odhiambo2015b). Notwithstanding, financial development is the final result of development. Under this scenario, it implies that the hegemonic and neoliberal arguments may be used to justify the need for isolation in view of increasing financial development. These arguments also double as channels that may dissuade openness or motivate isolation. We discuss these arguments in detail below.

First, hegemonic deterrence to openness which has been clarified in Section i maintains that governments may be averse to opening up their economies because openness, especially in the perspective of globalisation, is viewed as a hidden attempt by the more powerful nations and corporations to control the less powerful. This view is well articulated in a study on recent advances in finance for inclusive development by Asongu and Nwachukwu (Reference Asongu and Nwachukwu2017), a study which has been motivated by the hegemonic perspective. Accordingly, the following facts are for the most part traceable to growing openness. World Hunger (2010) has maintained that the principal cause of hunger and poverty in the contemporary world is a globalised economic system which encourages a very tiny minority to own a vast majority of global wealth, whereas the rest of the world is just left to survive. Global inequality has been rising over the past decades (Freeman Reference Freeman2010; Milanovic Reference MILANOVIC2011) and according to Joseph Stiglitz: ‘There has been no improvement in well-being for the typical American family for 20 years. On the other side, the top one percent of the population gets 40 per cent more in one week than the bottom fifth receive in a full year’ (Nabi Reference Nabi2013, p.10). Some narratives posit that only the top 1 per cent have benefited from the recent economic recovery (Cover Reference Covert2015). While in 2015 the income of the top 1 per cent was estimated to exceed that of the bottom 99 percent by 2016 (Oxfam 2015), in 2017 eight men in the world owned the same wealth as half of the world's population or 3.6 billion people (Oxfam 2017).

Second, the neoliberal deterrent to openness may build on the evidence that openness has been detrimental to financial development owing of the intensity and magnitude of global crisis. This position can be summarised by Buckle (Reference Buckle2009): ‘The modern era of globalisation has been associated with significant economic transformation around the world, but also an increasing frequency of financial crises. According to Eichengreen and Bordo (Reference Eichengreen and Bordo2002) there were 39 national or international financial crises between 1945 and 1973. Their frequency increased to 139 between 1973 and 1997, culminating in the Asian financial crisis. These crises occurred predominantly, but not exclusively, in emerging economies’ (Buckle Reference Buckle2009, p. 36).

Future studies can improve the extant knowledge by assessing whether established linkages withstand further empirical validity when ‘contemporary development’ is replaced with ‘historic development’ as an outcome variable. Moreover, assessing the relationship between isolation and other macroeconomic outcomes is also an interesting future research direction. The main caveat of the study is that the findings can be interpreted exclusively as relationships, not causality. Hence, as more data become available, it will be interesting to assess whether the established linkages hold from the perspective of causality.

Appendix: Data sources and summary statistics of variables

Table A1. Definitions and sources of variables

Table A2. Descriptive statistics

Table A3. Correlation matrix (to add geographical isolation and aerial isolation)