1. Introduction

The Gondwana supercontinent formed by the closure of the Mozambique Ocean and subsequent amalgamation of East and West Gondwana during the Pan-African Orogeny at the end of the Neoproterozoic Era (e.g. Stern, Reference Stern1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011). This led to the formation of a 6000 km long accretionary orogen within Gondwana that extends from Arabia to East Africa and into Antarctica and is known as the East African Orogen (e.g. Stern, Reference Stern1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013), also referred to as the Transgondwanan supermountain (Squire et al. Reference Squire, Campbell, Allen and Wilson2006). In NE Africa, the Pan-African Orogeny involved the collision of Archaean cratons and the Saharan Metacraton with the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Fig. 1a). The latter evolved between 565 and 870 Ma and primarily comprises Neoproterozoic juvenile oceanic island arcs (e.g. Stern, Reference Stern1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Johnson, Reference Johnson2014).

Fig. 1. (a) Reconstruction of Gondwana in the Cambrian showing the main geotectonic units (modified after Avigad et al. Reference Avigad, Morag, Abbo and Gerdes2017). (b) Simplified geological map of North Gondwana showing present-day distribution of Precambrian basement rocks and Cambrian–Ordovician sediments (modified after Avigad et al. Reference Avigad, Gerdes, Morag and Bechstädt2012). Black arrows indicate the palaeocurrent directions of Cambrian–Ordovician sediments. Note that for illustration purposes the Red Sea has been closed, showing the Arabian–Nubian Shield (ANS) as a single entity. Kh – Khida terrane.

After the assembly of Gondwana during the early Palaeozoic, a thick pile of quartz-rich sandstones was deposited across northern Gondwana (Fig. 1b), originally eroded from the Pan-African orogens (e.g. Garfunkel, Reference Garfunkel2002; Burke et al. Reference Burke, MacGregor, Cameron, Arthur, MacGregor and Cameron2003; Avigad et al. Reference Avigad, Sandler, Kolodner, Stern, McWilliams, Miller and Beyth2005; Meinhold et al. Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013). The high mineral maturity of the sediment can be attributed to either long transport distances and/or multi-stage sedimentary recycling (e.g. Garfunkel, Reference Garfunkel2002; Morag et al. Reference Morag, Avigad, Gerdes, Belousova and Harlavan2011) or strong chemical weathering at the time of deposition (e.g. Avigad et al. Reference Avigad, Sandler, Kolodner, Stern, McWilliams, Miller and Beyth2005). The similarity of detrital zircon U–Pb age spectra in Palaeozoic sandstones throughout Gondwana let Squire et al. (Reference Squire, Campbell, Allen and Wilson2006) postulate the existence of large sediment fans that brought detritus from the East African Orogen towards the continental margins. Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013) extended the super-fan model to the northern Gondwana margin evaluating detrital zircon age spectra from Cambrian–Ordovician sandstones of North Africa, the Sinai Peninsula and the northwesternmost part of the Arabian Peninsula. Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019 a) used a more extensive dataset, including also peri-Gondwana units, and evaluated the detrital zircon age spectra, using multivariate data analysis. Detrital zircon data from Lower Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks revealed three contrasting provenance end-members of the former Gondwanan shelf, namely the Avalonian, West African and East African – Arabian zircon provinces (Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019 a, b). The East African – Arabian zircon province corresponds to the Gondwana super-fan system of Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013). Saudi Arabia would lie more distal along the sediment path to the NE. However, the Gondwana super-fan model has not been tested yet for Saudi Arabia. Besides that, a thorough provenance analysis of detrital zircon ages from the Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia does not yet exist.

In the present study, we analysed 24 sandstone samples from the Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia (Fig. 2) to determine their detrital zircon U–Pb age spectra using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). The data are essential for refining the model of the Gondwana super-fan system of Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013) at a more distal location and thus for refining the East African – Arabian zircon province of Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019 a, b). In addition, they provide complementary provenance information for the Palaeozoic sandstones on the Arabian Peninsula. A more thorough understanding of the origin of these sedimentary units is important for reconstructions of palaeosource areas and sediment transport and gives novel insights into the erosion history of the East African Orogen. Besides that, the recognition of single zircon grains with up to Eoarchaean (3.6–4.0 Ga) ages in Palaeozoic sandstones of Saudi Arabia contributes further to the discussion whether hitherto unknown Early Archaean basement can be found in the Middle East (see Paquette & Le Pennec, Reference Paquette and Le Pennec2012, Reference Paquette and Le Pennec2013; Nutman et al. Reference Nutman, Mohajjel, Bennett and Fergusson2014) or whether such Early Archaean grains are rather recycled from old, distal sources.

Fig. 2. (a) Simplified geologic map of the Arabian Peninsula showing the study areas (modified after Pollastro et al. Reference Pollastro, Karshbaum and Viger1998). For simplification, the Tethyan ophiolite complexes in Oman have been omitted. IS – Israel, JO – Jordan, KU – Kuwait, UAE – United Arab Emirates. (b) Geologic map of the southern Saudi Arabian study area (‘Wajid area’) (modified after Keller et al. Reference Keller, Hinderer, Al-Ajmi, Rausch, Martini, French and Pérez Alberti2011). (c) Geologic map of the southern Saudi Arabian study area (‘Tabuk area’) (modified after Pollastro et al. Reference Pollastro, Karshbaum and Viger1998). For simplification, the sample prefix AB-SA has been avoided in the sample localities shown in (b) and (c).

2. Geological setting

In Saudi Arabia, the Palaeozoic succession crops out in a narrow band along the southern, eastern and northern margin of the Arabian Shield (Fig. 2a), which forms the eastern part of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Fig. 1). The latter is a complex amalgamation of numerous intra-oceanic island arc terranes accreted between 630 and 870 Ma, with igneous activity extending until 565 Ma (Kröner, Reference Kröner1985; Stern, Reference Stern1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Johnson, Reference Johnson2014). During the late Neoproterozoic, terrestrial sedimentary basins formed in which molasse was deposited under subaerial to shallow-water conditions, and variably interlayered with volcaniclastic rocks (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011, Reference Johnson, Halverson, Kusky, Stern and Pease2013). The Neoproterozoic rocks of the Arabian Shield are overlain with an erosional contact by Palaeozoic sandstones (Fig. 3a). Deposition took place from Cambrian to Permian times (Powers et al. Reference Powers, Ramirez, Redmond and Elberg1966; Powers, Reference Powers and Dubertret1968; Laboun, Reference Laboun2010) (Fig. 3a). Sedimentary environments varied, mainly ranging from fluvial braided stream setting to shallow marine, prodeltaic and open marine conditions (Dabbagh & Rogers, Reference Dabbagh and Rogers1983; Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995; Al-Ajmi et al. Reference Al-Ajmi, Keller, Hinderer and Filomena2015). The sediments were deposited on a stable continental shelf at a passive margin from the Cambrian until at least the Devonian (Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995; Sharland et al. Reference Sharland, Archer, Casey, Davies, Hall, Heward, Horbury and Simmons2001). The changes in accommodation space were primarily controlled by eustacy (Sharland et al. Reference Sharland, Archer, Casey, Davies, Hall, Heward, Horbury and Simmons2001). Low subsidence rates and the high stability of the Arabian Plate during most of the Palaeozoic resulted in a ‘layer cake’ stratigraphy (Bishop, Reference Bishop and Al-Husseini1995), although several erosional hiatuses and stratigraphic unconformities exist in the Palaeozoic succession (Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995). The erosional hiatuses separating sedimentary units are used for lithostratigraphic correlations (Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995; Laboun, Reference Laboun2010) (Fig. 3a). The Palaeozoic succession shows evidence for two Gondwana glaciations during the Late Ordovician (Hirnantian) (Clark-Lowes, Reference Clark-Lowes2005; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Hinderer, Al-Ajmi, Rausch, Martini, French and Pérez Alberti2011) and Carboniferous–Permian (McClure, Reference McClure1980; Alsharhan & Mohammed, Reference Alsharhan, Nairn and Mohammed1993; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Hinderer, Al-Ajmi, Rausch, Martini, French and Pérez Alberti2011). We refer to Keller et al. (Reference Keller, Hinderer, Al-Ajmi, Rausch, Martini, French and Pérez Alberti2011), Al-Ajmi et al. (Reference Al-Ajmi, Keller, Hinderer and Filomena2015) and Bassis et al. (Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a) for details about sedimentary facies and depositional environment.

Fig. 3. (a) Simplified stratigraphic column of both study areas. Modified after (1) Al-Ajmi et al. (Reference Al-Ajmi, Keller, Hinderer and Filomena2015), (2) Laboun (Reference Laboun2010), (3) Sharland et al. (Reference Sharland, Archer, Casey, Davies, Hall, Heward, Horbury and Simmons2001) and (4) Haq & Schutter (Reference Haq and Schutter2008). The dashed vertical line in the ‘Sea-level changes’ column represents an approximation of the present-day sea level. The ‘Climate’ column shows time interval with icehouse (cold) and greenhouse (warm) conditions. AP – Arabian plate sequence stratigraphy. PR – Proterozoic. (b) Thin-section photomicrographs of some representative samples from the Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia under regular view (left-hand side) and with crossed polarizers (right-hand side). The Lower Palaeozoic sample is a highly mature and well-sorted quartz arenite from the Dibsiyah Formation (AB-SA79), typical for most of the Palaeozoic succession. The Upper Palaeozoic sample is an arkose from the Juwayl Formation (AB-SA98) with intense calcite cementation. Mineral abbreviations: qtz – quartz; k-fsp – kali-feldspar; cc – calcite. We refer to Bassis et al. (Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016a, b) for details of the composition and maturity of the Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia and the samples analysed in this study.

Siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, mainly quartz arenites, dominate the Lower Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia (e.g. Fig. 3b; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a). The dominance of the stable minerals, such as zircon, tourmaline and rutile (high ZTR index, as defined by Hubert, Reference Hubert1962), indicating sediment maturity, among the transparent heavy mineral assemblage characterizes the Lower Palaeozoic sandstones (Babalola, Reference Babalola1999; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Babalola and Hariri2004; Knox et al. Reference Knox, Franks and Cocker2007; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b). Upper Palaeozoic sandstones are more feldspar-rich (Fig. 3b) and contain unstable transparent heavy minerals like garnet and/or staurolite (e.g. Knox et al. Reference Knox, Franks and Cocker2007; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b).

Whole-rock geochemistry and heavy mineral data reveal distinct changes in provenance between the Palaeozoic sandstones in central/northern (Tabuk area) and southern (Wajid area) Saudi Arabia (Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a, b) (Fig. 2a). Cambrian–Ordovician sandstones seem to be first-cycle sediments, probably sourced from the ‘Pan-African’ basement. The high mineralogical maturity of the sediment and the lack of apparent recycling trends seem to be a mixture of compositional variation of source rocks and reworking during deposition, coupled with intensive source area weathering and low sedimentation rates (see discussion in Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a). The overlying Upper Ordovician glaciogenic deposits likely consist of recycled Cambrian–Ordovician material. The Devonian–Permian sandstones show a significant influx of fresh basement material. The exact source for the Palaeozoic detritus is still under debate. The adjacent Arabian Shield most likely was a major contributor throughout the Palaeozoic, but far distant sources have to be taken into account as well (e.g. Al-Harbi & Khan Reference Al-Harbi and Khan2008, Reference Al-Harbi and Khan2011; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b). Possible source areas to the south include Archaean to Palaeoproterozoic terranes in Yemen (e.g. Babalola, Reference Babalola1999; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Babalola and Hariri2004; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b), metamorphic terranes in Eritrea and Sudan, as well as the Mozambique Belt in East Africa (Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b).

3. Methods

Samples analysed in this study were previously studied using thin-section petrography and whole-rock geochemistry (Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a) and conventional heavy mineral analysis including electron microprobe studies to determine the chemical composition of garnet and rutile grains (Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b). Samples were taken from surface outcrops in the Tabuk and Wajid study areas, respectively (Fig. 2). Lithology, stratigraphy and geographic coordinates of the studied samples are given in Table 1. After rock crushing, milling and dry sieving to obtain the 63−125 μm fractions, the heavy mineral fractions were separated using sodium polytungstate with a density of 2.85 g mL−1 (see Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b for details). Zircon selection from the heavy fractions was achieved by hand-picking under a binocular microscope. Zircon grains were fixed in epoxy resin mounts and polished to expose the interior of the grains. Prior to the analyses, transmitted light photomicrographs were taken with a polarizing microscope equipped with a camera system to study the zircon shape and roundness. Cathodoluminescence (CL) imaging was applied using a JEOL JXA 8900 RL electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) equipped with a CL detector at the University of Göttingen (Department of Geochemistry, Geoscience Center) to reveal the internal structures (e.g. growth zones) and to guide spot placement in the zircon grains.

Table 1. Sample information. The samples are given for each study area in stratigraphic order from old (bottom) to young (top). Locations are given in geographical coordinates (WGS84). Detailed information on the petrography, whole-rock geochemistry and heavy mineral data of each sample is given in Bassis et al. (Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016a, b). Last two columns: summary of detrital zircon ages of samples analysed in this study. Complete datasets used here are reported in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756820000576

The U–Pb age determination was performed on a sector-field ICP-MS (Element2, ThermoFisher) coupled to a 193 nm Photon Machines Analyte G2 Excimer laser ablation system at the University of Münster (Institute of Mineralogy) following the procedure described in Lewin et al. (Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a). Isotope data were acquired on masses 202, 204, 206, 207 and 238. The mass 202 was used to quantify interference of 204Hg on 204Pb. A common Pb correction was only applied to an analysis if the fraction of common 206Pb to total 206Pb exceeded 1 %. A summary of the laser ablation ICP-MS operation parameters is given in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756820000576.

Data reduction follows the procedure described by Kooijman et al. (Reference Kooijman, Berndt and Mezger2012). To account for the lower precision of 207Pb/206Pb values for young zircons, the data were filtered using two criteria as in previous detrital zircon provenance studies (Löwen et al. Reference Löwen, Meinhold, Güngör and Berndt2017; Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a): accepted were all zircon ages (1) with 90–110 % concordance [100 × (206Pb/238U/207Pb/235U)] for grains younger than 1200 Ma, and (2) with 90–110 % concordance [100 × (206Pb/238U /207Pb/206Pb)] for grains older than 1200 Ma. This age was chosen due to the natural gap of zircon ages in the analysed samples. The R-package Provenance (Vermeesch et al. Reference Vermeesch, Resentini and Garzanti2016) was used for visualization of the zircon age spectra as kernel density estimates (KDE) and for multi-sample comparison using multidimensional scaling (MDS). MDS is a useful technique to interpret, for example, large detrital zircon U–Pb age datasets by statistically comparing the data and visualizing all in a simple two-dimensional map in which ‘similar’ samples plot close together and ‘dissimilar’ samples plot far apart (e.g. Vermeesch, Reference Vermeesch2013; Vermeesch & Garzanti, Reference Vermeesch and Garzanti2015). The international chronostratigraphic chart of Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Harper, Gibbard and Fan2018) was used as a stratigraphic reference for data interpretation.

4. Results

From the 24 sandstone samples of the Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia, in total, 1915 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 1734 ages (91 % of all zircons) are 90–110 % concordant (Table 1) using the respective data filters described in Section 3. Complete datasets used here are reported in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756820000576.

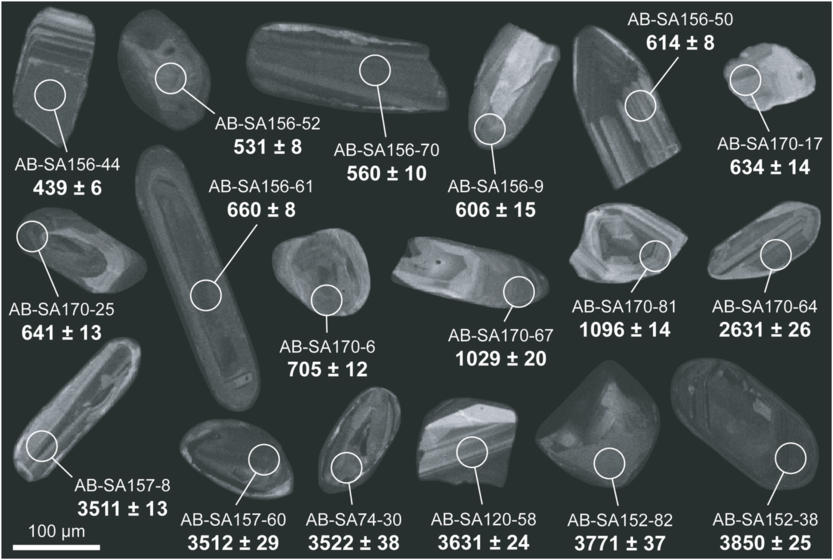

The majority of the detrital zircons are clear or translucent. Subrounded to rounded grains are dominant. Most of the zircons show undisturbed oscillatory (magmatic) zoning in the CL images (Fig. 4). Many grains also show regrowth features suggesting that these grains have subsequently recrystallized during late- or post-magmatic cooling (Corfu et al. Reference Corfu, Hanchar, Hoskin, Kinny, Hanchar and Hoskin2003). Zircons with xenocrystic cores and clearly zoned rims are minor.

Fig. 4. Cathodoluminescence images of representative zircon grains from samples analysed in this study with the location of the LA-ICP-MS analysis spot and the corresponding 206Pb/238U age reported with ±2σ uncertainty in Ma for grains younger than 1.2 Ga and 207Pb/206Pb age reported with ±2σ uncertainty in Ma for grains older than 1.2 Ga. The number after the sample name corresponds to the analysis spot as indicated in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756820000576.

Five main detrital zircon populations are identified in the Palaeozoic sandstones of the Wajid and Tabuk areas of Saudi Arabia, with main age peaks at 625 Ma, 775 Ma, 980 Ma, 1840 Ma and 2480 Ma (Fig. 5). Detrital zircons with Ediacaran–Cryogenian (541–720 Ma) ages are most prominent, making up 36 % of all concordant dates. A minor amount of all concordant zircon grains, c. 4 %, show Palaeozoic (340–541 Ma), and c. 0.6 % show up to Palaeo- and Eoarchaean (3200 to <4000 Ma) ages.

Fig. 5. Kernel density estimate plot showing a summary of U–Pb analytical detrital zircon data for all samples analysed in this study. Only grains with 90 to 110 % concordance are shown. n – number of zircon ages. For simplification, and as the majority of the detrital zircons are older than Phanerozoic, no chronostratigraphic subdivisions for Era and Period are shown for the Phanerozoic Eon. Abbreviations of Periods: E. – Ediacaran, C. – Cryogenian, T. – Tonian, St. – Stenian, Ec. – Ectasian, Ca. – Calymmian, Sta. – Statherian, Oro. – Orosirian, Rhy. – Rhyacian, Sid. – Siderian. Abbreviations of Eras: Neoprot. – Neoproterozoic, Neo. – Neoarchaean, Meso. – Mesoarchaean, Palaeo. – Palaeoarchaean, Eo. – Eoarchaean.

In the following, the zircon data are presented independently for both study areas starting for each with the oldest stratigraphic formation. We also mention the youngest zircon age for each sample/formation. However, we caution against overinterpretation of these ages in regard to estimation of the maximum age of deposition. A small amount of Pb loss can shift the U–Pb zircon age along the concordia curve toward younger ages, but the age will remain concordant using the filtering criteria as outlined in Section 3. Nonetheless, Dickinson & Gehrels (Reference Dickinson and Gehrels2009) could exemplarily show for the Mesozoic sedimentary succession of the Colorado Plateau that the youngest single grain zircon ages are compatible with depositional age for >90 % of the samples, and lie within 5 Ma of depositional age for 60 % of the samples. Also, the weighted arithmetic mean of the youngest population of detrital zircon ages is often used for the estimation of the maximum age of deposition (Dickinson & Gehrels, Reference Dickinson and Gehrels2009). However, we did not apply that here as (1) not each sample provided the required minimum number (n ≥ 3) of grains for the youngest zircon population that overlap in age at 2 standard deviations and (2) this approach does also have its shortcomings (see Spencer et al. Reference Spencer, Kirkland and Taylor2016 for details).

4.a. Wajid area

Nine Palaeozoic sandstone samples from the Wajid area were analysed for their detrital zircon age spectra (Figs 2b, 6, 7; Table 1). In total, 704 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 636 ages (90.3 % of all zircons) are 90–110 % concordant.

Fig. 6. Kernel density estimate (KDE) plots of the zircon age spectra in samples from the Wajid area (left) and Tabuk area (right) of Saudi Arabia. Samples are arranged from bottom to top according to their stratigraphic age. Only grains with 90 to 110 % concordance are shown. n – number of zircon ages.

Fig. 7. Bar chart showing the relative abundances of the defined age groups in the analysed samples from the Wajid and Tabuk areas of Saudi Arabia. Samples are arranged from bottom to top according to their stratigraphic age.

Dibsiyah Formation (Cambrian–Ordovician): Both samples show similar zircon age spectra. The majority of all grains yielded Ediacaran–Cryogenian (541 to <720 Ma; 49 % and 44 %, respectively) and Tonian (720 to <900 Ma; 33 % and 25 %, respectively) ages (Fig. 7). Sample 74 shows a higher amount of Tonian–Stenian (900–1200 Ma) ages than sample 79 (i.e. 12 % versus 5 %). This correlates with a higher amount of Ectasian–Siderian (1200 to <2500 Ma) zircon ages in sample 74 than in sample 79 (i.e. 10 % versus 3 %). Palaeozoic zircon grains are minor (5 %), as are Archaean zircon grains (4 %). The youngest zircon age in the Dibsiyah Formation is 481 ± 22 Ma (sample 79, analysis number, #: 56) whereas the oldest age is 3522 ± 38 Ma (sample 74, #: 30) (Fig. 4).

Sanamah Formation (Upper Ordovician): From two samples (73 and 62), in total, 164 zircon ages have been obtained of which 136 have been used for interpretation. Both samples show very similar zircon age spectra, with most grains yielding Ediacaran–Cryogenian (32 % and 33 %, respectively) and Tonian (32 % and 33 %, respectively) ages (Fig. 7). Sample 73 shows more Tonian–Stenian (900–1200 Ma) ages than sample 62 (i.e. 21 % versus 13 %). The amount of Ectasian–Siderian zircon ages is almost equal in both samples (i.e. 10 % versus 8 %). Palaeozoic zircon grains are minor (5 % and 6 %, respectively). Sample 62 yielded more Archaean ages than sample 73 (6 % and 1 %, respectively). The youngest zircon age in the Sanamah Formation is 453 ± 10 Ma (sample 73, #: 33). The oldest age is 2735 ± 21 Ma (sample 62, #: 3).

Khusayyayn Formation (Devonian): In total, 260 zircon ages from three samples (118, 90 and 87) have been obtained, of which 244 have been used for interpretation. Samples 90 and 87 show similar zircon spectra, with the majority of all grains yielding Ediacaran–Cryogenian (22 % and 26 %, respectively), Tonian–Stenian (34 % and 32 %, respectively) and Ectasian–Siderian (25 % and 18 %, respectively) ages (Fig. 7). The amount of Tonian (13 % and 10 %, respectively) ages is less compared with older Palaeozoic sandstone samples. Sample 118 shows a different zircon age spectrum given that it has more grains with Ediacaran–Cryogenian (34 %) and Tonian (30 %) ages (Fig. 7). Palaeozoic zircon grains make up less than 3 %. The amount of Archaean zircon grains ranges from 4 to 9 %. The youngest zircon age in the Khusayyayn Formation is 494 ± 22 Ma (sample 90, #: 11) whereas the oldest zircon age is 3347 ± 13 Ma (sample 87, #: 89).

Juwayl Formation (Carboniferous–Permian): From two samples (100 and 98), in total, 114 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 106 have been used for interpretation. The low number of obtained ages is due to the low zircon fertility of sample 98. The majority of the zircons fall into the Ediacaran–Cryogenian (40 % and 54 %, respectively) and Tonian (24 % and 21 %, respectively) age groups (Fig. 7). The amount of Tonian–Stenian (900–1200 Ma) ages is broadly similar in both samples (i.e. 12 % versus 17 %) whereas the amounts of Ectasian–Siderian ages are different (i.e. 18 % versus 8 %). Both the youngest (362 ± 8 Ma, #: 72) and oldest (2612 ± 23 Ma, #: 25) zircon ages in the Juwayl Formation come from sample 100.

4.b. Tabuk area

Fifteen Palaeozoic sandstone samples from the Tabuk area were analysed for their detrital zircon age spectra (Figs 2c, 6, 7; Table 1). In total, 1211 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 1098 ages (90.7 % of all zircons) are 90–110 % concordant.

Saq Formation (Cambrian–Ordovician): From two samples (170 and 169), in total, 165 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 141 have been used for interpretation. In both samples, Ediacaran–Cryogenian (42 % and 33 %, respectively), Tonian (26 % and 15 %, respectively) and Tonian–Stenian (14 % and 31 %, respectively) age groups are most prominent but in varying amounts (Fig. 7). Ectasian–Siderian (i.e. 12 % versus 13 %) and Archaean (i.e. 8 % versus 9 %) zircon ages are minor, with almost equal amounts in both samples. The youngest (549 ± 11 Ma, #: 39) and oldest (2660 ± 20 Ma, #: 3) zircon ages in the Saq Formation come from sample 169.

Qasim Formation (Ordovician): In total, 299 zircon ages from four samples (144/1, 145, 126 and 124) have been obtained, of which 259 have been used for interpretation. The oldest samples, 144/1 and 145, show similar zircon spectra, with the majority of all grains yielding Ediacaran–Cryogenian (47 % and 43 %, respectively) and Tonian (27 % and 41 %, respectively) ages (Fig. 7). Tonian–Stenian (900–1200 Ma) ages are only minor (6 % and 2 %, respectively). Ectasian–Siderian (14 % and 8 %, respectively) and Archaean (4 % and 2 %, respectively) ages are subordinate present in both samples. The youngest samples, 126 and 124, show similar zircon spectra. Compared with the oldest samples, however, they show lower amounts of Ediacaran–Cryogenian (27 % and 26 %, respectively), slightly lower to almost equal amounts of Tonian (31 % and 22 %, respectively) but higher amounts of Tonian–Stenian (19 % and 16 %, respectively) and Ectasian–Siderian (19 % and 21 %, respectively) ages (Fig. 7). There is an increase in the amount of Palaeozoic zircon grains with stratigraphy from old (1 %) to young (9 %) (Fig. 7). The youngest and oldest zircon ages in the Qasim Formation are 476 ± 10 Ma (sample 145, #: 14) and 2795 ± 16 Ma (sample 144/1, #: 73), respectively.

Sarah and Zarqa formations (Upper Ordovician): In total, 165 zircon ages were obtained, with 148 ages being 90–110 % concordant. Sample 123/2, from the Sarah Formation, and sample 132/1, from the Zarqa Formation, show similar zircon age spectra, with the majority of the ages falling into the Ediacaran–Cryogenian (45 % and 37 %, respectively) and Tonian (25 % for each sample) age groups (Fig. 7). The amounts of Tonian–Stenian (9 % and 11 %, respectively) and Ectasian–Siderian (11 % for each sample) zircon ages are almost equal in both samples. Archaean ages (1 % and 3 %, respectively) are almost absent. Interestingly, the increase in the amount of Palaeozoic zircon grains with stratigraphy from old (9 % in sample 123/2) to young (13 % in sample 132/1) seems to continue in the Upper Ordovician (Fig. 7). Sample 132/1 yielded both the youngest (466 ± 14 Ma, #: 36) and oldest (3066 ± 31 Ma, #: 30) zircon ages among the Upper Ordovician sample set.

Tawil, Jauf and Jubah formations (Devonian): In total, 407 zircon ages from five samples (157, 156, 160/T, 152 and 150) have been obtained, of which 384 have been used for interpretation. The oldest Devonian samples (157 and 156) are from the Tawil Formation, and they show different zircon spectra compared to the remaining Devonian samples. In both Tawil Formation samples, Ediacaran–Cryogenian (33 % and 40 %, respectively) ages are most prominent followed by Tonian (20 % and 17 %, respectively) and Tonian–Stenian (29 % and 19 %, respectively) zircon age groups (Fig. 7). The amount of zircon ages belonging to the Ectasian–Siderian (10 % and 7 %, respectively) age group is almost equal in both samples. Archaean ages (8 % and 12 %, respectively) are more prominent compared to samples from Lower Palaeozoic formations. The remaining Devonian samples from the Jauf and Jubah formations show lower amounts of Ediacaran–Cryogenian (less than 23 %) but higher amounts of Tonian (23–24 %) and much higher amounts of Tonian–Stenian (33–38 %) ages compared to the samples from the Tawil Formation (Fig. 7). The amounts of zircon ages belonging to the Ectasian–Siderian (7–11 %) and Archaean (7–10 %) age groups in the Jauf and Jubah formations are similar to those of the Tawil Formation samples (Fig. 7). The youngest zircon age in the Devonian samples is 439 ± 6 in sample 156 (#: 44). The Devonian samples yielded a high amount of Palaeo- and Eoarchaean ages and, surprisingly, the oldest zircon ages among the Palaeozoic samples from Saudi Arabia: 3771 ± 37 Ma (#: 82) and 3850 ± 25 Ma (#: 38) in the Jubah Formation sample 152 (Figs 4, 5).

Unayzah Formation (Carboniferous–Permian): From two samples (129 and 120), in total, 175 zircon ages have been obtained, of which 166 have been used for interpretation. Both samples show similar zircon age spectra, with the majority of the ages falling into the Ediacaran–Cryogenian (46 % and 49 %, respectively) and Tonian (19 % and 25 %, respectively) age groups (Fig. 7). Sample 120 has more Tonian–Stenian (900–1200 Ma) zircon ages than sample 129 (i.e. 14 % versus 9 %). The amount of Ectasian–Siderian ages is almost equal in both samples (i.e. 11 % versus 10 %). Palaeozoic (both samples 4 %) and Archaean (7 % and 4 %, respectively) ages are minor present. Both the youngest (340 ± 8 Ma, #: 78) and oldest (3631 ± 24 Ma, #: 58) zircon ages in the Unayzah Formation come from sample 120.

5. Discussion

The first comprehensive detrital zircon age analysis of Palaeozoic sandstones from Saudi Arabia presented here revealed three prominent age populations at 625 Ma, 775 Ma and 980 Ma, accompanied by two minor age populations at 1840 Ma and 2480 Ma (Fig. 5). These age populations are similar to those identified by Garzanti et al. (Reference Garzanti, Vermeesch, Andò, Vezzoli, Valagussa, Allen, Kadi and Al-Juboury2013) in two Palaeozoic sandstone samples from the Tabuk area. However, we do not further discuss these two samples due to their uncertain stratigraphic assignment. For example, Garzanti et al. (Reference Garzanti, Vermeesch, Andò, Vezzoli, Valagussa, Allen, Kadi and Al-Juboury2013) described an Ordovician sandstone sample, which they assigned to the ‘Tabuk Formation’. However, that term has been discarded long ago (see Laboun, Reference Laboun2010).

5.a. Possible source areas

As most of the zircons show oscillatory zoning and some show regrowth features in the CL images (Fig. 4), igneous rocks are the primary source of these grains. The Ediacaran–Cryogenian (541 to <720 Ma) and the Tonian (720 to <900 Ma) age groups represent igneous events associated with the Pan-African Orogen. Igneous crustal domains in the Arabian–Nubian Shield and the Eastern Granulites–Cabo Delgado Nappe Complex in the Mozambique Belt are likely sources, in agreement with palaeocurrent data, as igneous rocks with ages between 541 and 900 Ma are well known from these areas (e.g. Kröner, Reference Kröner1985; Stern, Reference Stern1994; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Andresen, Collins, Fowler, Fritz, Ghebreab, Kusky and Stern2011; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013; Johnson, Reference Johnson2014). Although it is difficult to narrow down the exact source, the 625 Ma zircon age peak in the studied samples (Fig. 5) is likely related to the youngest crustal growth phases in the Arabian–Nubian Shield, which are found in the eastern Arabian Shield and northern Nubian Shield. Also, 628 Ma old plutonic rocks occur in the western Nubian Shield (e.g. granodiorite at Gebel el-Asr in southern Egypt: Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Pease, Whitehouse, El-Sankary and Shalaby2019 a) and 630–500 Ma igneous rocks are known from the southern Nubian Shield (e.g. granitoids in the Southern Ethiopian Shield: Teklay et al. Reference Teklay, Kröner, Mezger and Oberhänsli1998; Yibas et al. Reference Yibas, Reimold, Armstrong, Koeberl, Anhaeusser and Phillips2002; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Ali, Abdelsalam, Wilde and Zhou2012). The 775 Ma zircon age peak (Fig. 5) is likely related to the oldest crustal growth phases, which are found in the western Arabian Shield and the southern Nubian Shield (Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013).

The few early Palaeozoic ages (439–541 Ma) reported in almost all of the samples (Fig. 7) could be derived from post-orogenic igneous rocks. Cambrian post-orogenic plutonic rocks are known from the Arabian–Nubian Shield and SE Africa and Madagascar (Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013). Cambrian and Ordovician alkaline and peralkaline plutonic rocks occur in Egypt and Sudan (Höhndorf et al. Reference Höhndorf, Meinhold and Vail1994; Woolley, Reference Woolley2001; Veevers, Reference Veevers2007). In addition, early Palaeozoic post-orogenic plutonic rocks, volcanic rocks and related products, such as volcanic ash beds (K-bentonites), as described from the Middle Ordovician of Libya (Ramos et al. Reference Ramos, Navidad, Marzo, Bolatti, Albanesi, Beresi and Peralta2003), and ascribed to volcanic activity along the northern margin of Gondwana during that time, could be an additional or alternative source (Meinhold et al. Reference Meinhold, Morton, Fanning, Frei, Howard, Phillips, Strogen and Whitham2011; Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a). Late Devonian – Early Carboniferous zircons may come from within-plate, anorogenic igneous rocks from localized regions of NE Africa and Arabia, as known, for example, from Levant and its vicinity (e.g. Stern et al. Reference Stern, Ren, Ali, Förster, Al Safarjalani, Nasir, Whitehouse, Leybourne and Romer2014; Golan et al. Reference Golan, Katzir and Coble2018). The youngest zircon ages in the studied samples should not be overinterpreted, as they are commonly single ages. Similar to the detrital zircons from Ethiopia (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a), some of the early Palaeozoic zircons from sandstones of Saudi Arabia were corrected for common Pb, and thus they may be over-corrected, leading to younger ages.

The pre-900 Ma zircon ages in the studied samples may have originally been xenocrystic zircons in Pan-African igneous rocks of the East African Orogen. This, however, will not be applicable to the majority of the pre-900 Ma ages recorded in the studied samples. Stern et al. (Reference Stern, Ali, Liégeois, Johnson, Wiescek and Kattan2010) have shown that only 5 % of individually dated zircons from igneous rocks of the Arabian–Nubian Shield are older than 880 Ma, with prominent age populations at 0.9–1.15 Ga (Tonian–Stenian), 1.7–2.1 Ga (late Palaeoproterozoic), 2.4–2.8 Ga (Palaeoproterozoic–Neoarchaean) and 3.2–3.5 Ga (Palaeoarchaean). Furthermore, most of the zircons analysed here have oscillatory (magmatic) zoning in the CL images, with xenocrystic cores a very minor component. Therefore, other sources than ‘xenocrystic’ zircons need to be considered for the pre-900 Ma detrital zircons.

The nearest basement rocks with Tonian–Stenian (900 to <1200 Ma) ages are documented from Sudan and the Sinai Peninsula. Kröner et al. (Reference Kröner, Stern, Dawoud, Compston and Reischmann1987) described high-grade metasedimentary gneisses at Sabaloka in Sudan containing detrital zircons ranging in age from 2.6 to 0.9 Ga. Küster et al. (Reference Küster, Liégeois, Matukov, Sergeev and Lucassen2008) described 900–920 Ma-old metamorphic zircons from basement rocks of the Bayuda terrane in Sudan, which indicate an orogenic event preceding the East African Orogeny. Both the Saboloka and Bayuda basement units belong to the eastern Saharan Metacraton (Fig. 1b). Be’eri-Shlevin et al. (Reference Be’eri-Shlevin, Katzir, Whitehouse and Kleinhanns2009) reported 0.9–1.13 Ga-old zircons from the Sa’al schist in Sinai. This, together with the euhedral shape of some of these grains and the lack of other pre-Neoproterozoic zircon ages in the Sa’al schist is taken as evidence for the presence of 0.9–1.1 Ga-old crust at the NE margin of western Gondwana prior to the formation of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Be’eri-Shlevin et al. Reference Be’eri-Shlevin, Katzir, Whitehouse and Kleinhanns2009). Such crust is preserved as calc-alkaline volcanic and intrusive rocks (1.02–1.03 Ga) within the Sa’al metamorphic complex on Sinai (Be’eri-Shlevin et al. Reference Be’eri-Shlevin, Eyal, Eyal, Whitehouse and Litvinovsky2012). Although the Sinai basement is in proximity to the study area, at least to the Tabuk area, sediment supply from the 1 Ga basement seems unlikely, as palaeocurrent data point toward a southerly provenance (Dabbagh & Rogers, Reference Dabbagh and Rogers1983; Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995; Babalola, Reference Babalola1999; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Babalola and Hariri2000). However, at least for the Wajid area, a prevailing northward transport direction cannot be inferred for the entire Palaeozoic succession, as opposing (NW to SE) transport directions occur in the glaciogenic units of the Upper Ordovician Sanamah Formation and the Carboniferous–Permian Juwayl Formation (Hinderer et al. Reference Hinderer, Keller, Al-Ajmi and Rausch2009; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Hinderer, Al-Ajmi, Rausch, Martini, French and Pérez Alberti2011; Al-Ajmi et al. Reference Al-Ajmi, Keller, Hinderer and Filomena2015). A change of the prevailing northward transport direction seems to have started during the Devonian because, in the Wajid area, dip measurements of cross-bedding indicate palaeocurrent directions to the north and NNE in the lower Khusayyayn Formation and already more easterly directions in the upper Khusayyayn Formation (Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995). The Arabian–Nubian Shield including its northernmost part on the Sinai Peninsula could thus be a possible source area. However, minor amounts of 1 Ga zircons are present in Neoproterozoic diamictites of northern Ethiopia (Avigad et al. Reference Avigad, Stern, Beyth, Miller and McWilliams2007) and the Eastern Desert of Egypt (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Stern, Manton, Johnson and Mukherjee2010). Thus, some 1 Ga zircons may have been recycled from Neoproterozoic siliciclastic sediments, but this probably does not account for the majority of the 1 Ga zircon grains in the studied Palaeozoic sandstones. The source of the 1 Ga zircons will be further discussed in Section 5.c in regard to the Gondwana super-fan system and the East African – Arabian zircon province, respectively.

Palaeoproterozoic and Archaean detrital zircons recorded in Palaeozoic sandstones of Saudi Arabia may have been recycled from Neoproterozoic sediments of the Arabian–Nubian Shield, as these sediments contain Palaeoproterozoic and Neo- and Mesoarchaean detrital zircon grains (Agar et al. Reference Agar, Stacey and Whitehouse1992; Wilde & Youssef, Reference Wilde and Youssef2002; Ali et al. Reference Ali, Stern, Manton, Johnson and Mukherjee2010). Alternatively, they may represent xenocrystic cores originally derived from igneous rocks of the Arabian–Nubian Shield, but this would only account for a small number of grains (see Stern et al. Reference Stern, Ali, Liégeois, Johnson, Wiescek and Kattan2010). A primary derivation from Palaeoproterozoic and Archaean basement is also likely, as meta-igneous rocks of such age occur in the vicinity of the study area, e.g. 1.66 Ga crust (and probably also older crust based on Sm–Nd isotope data) in the Khida terrane of the eastern Arabian Shield (Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Stoeser and Stacey2001), and 2.55–2.95 Ga crust in the Arabian Shield of Yemen (Whitehouse et al. Reference Whitehouse, Windley, Ba-Bttat, Fanning and Rex1998). The eastern Saharan Metacraton also contains Palaeoproterozoic and Archaean crustal components (e.g. Küster et al. Reference Küster, Liégeois, Matukov, Sergeev and Lucassen2008; Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Abu Anbar and Talavera2011; Kongnyuy et al. Reference Kongnyuy, Giulio and Satir2012; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Pease, Whitehouse, El-Sankary and Shalaby2019 b) and thus can be seen as a possible source area. This may be supported by the fact that the eastern and southeastern parts of the Saharan Metacraton were exposed at the surface and thus were prone to erosion throughout most of the Palaeozoic, according to palaeogeographic reconstructions (e.g. Torsvik & Cocks, Reference Torsvik and Cocks2013).

Although Palaeo- and Eoarchaean zircon ages make up only 0.6 % of the obtained concordant age spectrum (Fig. 5), they are of great interest, as pre-3.2 Ga crust is not known from anywhere in the surrounding area (e.g. Hargrove et al. Reference Hargrove, Stern, Kimura, Manton and Johnson2006; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Ali, Liégeois, Johnson, Wiescek and Kattan2010; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz, Abdelsalam, Ali, Bingen, Collins, Fowler, Ghebreab, Hauzenberger, Johnson, Kusky, Macey, Muhongo, Stern and Viola2013; Johnson, Reference Johnson2014). The exception is uppermost Palaeoarchaean basement rock in SW Egypt, i.e. 3.22 ± 0.02 Ga gneiss at Gebel Kamil (Bea et al. Reference Bea, Montero, Abu Anbar and Talavera2011) and 3.245 ± 0.05 Ga gneiss at Gebel Uweinat (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Pease, Whitehouse, El-Sankary and Shalaby2019 b). The Devonian samples yielded the highest amount of Palaeo- and Eoarchaean zircon ages compared to all other studied samples and, surprisingly, they yielded the oldest zircon ages yet recorded from Arabia and the surrounding area: 3771 ± 37 Ma (#: 82) and 3850 ± 25 Ma (#: 38) in the Jubah Formation sample 152 (Figs 4, 5). Similar old ages (3729–3769 Ma, n = 4) were reported from inherited zircon crystals in Neogene ignimbrites of Central Anatolia in Turkey, and this was suggested to be an indication for the presence of Early Archaean basement in the Anatolian subsurface (Paquette & Le Pennec, Reference Paquette and Le Pennec2012, Reference Paquette and Le Pennec2013). However, an alternative explanation such as derivation from a Gondwanan source and later reworking by sedimentary and/or igneous events has been put forward (Köksal et al. Reference Köksal, Toksoy-Köksal, Göncüoglu, Möller, Gerdes and Frei2013). Nutman et al. (Reference Nutman, Mohajjel, Bennett and Fergusson2014) reported an inherited zircon core of 3579 Ma from a Pan-African granite of the Sanandaj–Sirjan Zone and discussed it as the oldest crustal material yet found in Iran. The source of these old grains is not yet known. Archaean zircons may represent xenocrystic zircons assimilated from terrigenous sediment, may reflect assimilation of cryptic Archaean continental crust that underlies the juvenile crust of the Arabian–Nubian Shield (Hargrove et al. Reference Hargrove, Stern, Kimura, Manton and Johnson2006), or may indicate a more distal source area such as the Saharan Metacraton. It can be speculated that yet unknown terrigenous sediment and/or igneous rocks containing inherited up to Eoarchaean components may occur in the Saharan Metacraton. These rocks were later eroded, and the detrital material was transported by continental-scale river systems and/or glaciers toward the Arabian Peninsula.

5.b. Sample comparison

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) has successfully been applied to detrital zircon age datasets from Palaeozoic sandstones of northern Gondwana (Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019 a; Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a) and is applied here to Palaeozoic sandstones from Saudi Arabia (Section 5.b.1), followed by a comparison with samples from Ethiopia (Section 5.b.2). However, it is worth keeping in mind that quantitative comparisons of U–Pb age distributions can be biased because, for example, there is a grain-size dependence on age-data acquisition and interpretation (e.g. Yang et al. Reference Yang, Zhang and Wang2012; Ibañez-Mejia et al. Reference Ibañez-Mejia, Pullen, Pepper, Urbani, Ghoshal and Ibañez-Mejia2018).

5.b.1. Comparison of samples from Saudi Arabia

First, among the samples from Saudi Arabia, the Cambrian and Ordovician samples (Fig. 8a) are separately discussed from the Devonian to Permian samples (Fig. 8b) before discussing all samples in a single MDS plot (Fig. 8c). Among the Cambrian and Ordovician samples, there is no clear separation according to stratigraphic age or study area, i.e. Wajid versus Tabuk. However, among the Wajid samples, the Cambrian–Ordovician Dibsiyah Formation samples (74 and 79) differ from those of the Upper Ordovician Sanamah Formation (62 and 73), and the two samples from the Sanamah Formation are very similar in their zircon spectra (Fig. 8a). The Cambrian–Ordovician Saq Formation sample 169 from the Tabuk area shows some resemblance to the Cambrian–Ordovician Dibsiyah Formation sample 74 of the Wajid area whereas the Cambrian–Ordovician Saq Formation sample 170 from the Tabuk area shows the least similarity to the Cambrian–Ordovician Dibsiyah Formation of the Wajid area (Fig. 8a). The Ordovician Qasim Formation samples from the Tabuk area form two sample groups. Group 1 comprises the older samples 144/1 and 145 whereas group 2 comprises the younger samples 124 and 126 (Figs 7, 8a). Overall, these patterns among the Cambrian and Ordovician samples suggest times of a homogeneous sediment source and times of sediment supply from different sources to the Wajid and Tabuk areas.

Fig. 8. Non-metric multidimensional scaling maps for the detrital zircon age spectra of Palaeozoic sandstone analysed in this study. Only ages >500 Ma are used here due to the low reliability of younger ages following Lewin et al. (Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020a). The colours in the circles correspond to the colours used for the stratigraphy shown in Figure 3a.

Among the Devonian to Permian samples, there is a clear separation according to stratigraphic age, Devonian versus Carboniferous–Permian, but not according to the study area, i.e. Wajid versus Tabuk (Fig. 8b). Thus, during the Devonian the sediment provenance was relatively similar for both the Wajid and Tabuk areas. The sediment source changed in the Carboniferous–Permian but again it was similar throughout both study areas.

Comparing the Devonian to Permian samples with the Cambrian and Ordovician samples in an MDS plot reveals some interesting similarities (Fig. 8c). According to that, zircon populations of the Upper Palaeozoic sandstones resemble those of the Lower Palaeozoic sandstones in both study areas. However, the Upper Palaeozoic sandstone composition cannot simply be explained by sediment recycling of Lower Palaeozoic sandstones because the latter are mainly quartz arenites (Fig. 3b) with a dominance of zircon, tourmaline and rutile among the transparent heavy minerals (Babalola, Reference Babalola1999; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Babalola and Hariri2004; Knox et al. Reference Knox, Franks and Cocker2007; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b) whereas the Upper Palaeozoic are more feldspar-rich (Fig. 3b) and also contain unstable transparent heavy minerals like garnet and/or staurolite (e.g. Knox et al. Reference Knox, Franks and Cocker2007; Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 b). Thus, it is more likely that fresh basement rocks with zircon ages resembling that from basement rocks, which supplied sediment to the Lower Palaeozoic sandstones, also supplied detritus to the Upper Palaeozoic sandstones. Minor sediment recycling from Lower Palaeozoic sandstones may have occurred, but it certainly cannot account for the majority of the detrital material in the Upper Palaeozoic sandstones.

5.b.2. Comparison of samples from Saudi Arabia with those from Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, Palaeozoic successions are present around the Mekelle Basin in the Tigray province of northern Ethiopia and, to a minor extent, in the Blue Nile region in the west of the country, and comprise Upper Ordovician and Carboniferous–Permian glaciogenic sandstones (e.g. Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit and Bussert2018, and references therein). Comparing detrital zircon data from Upper Ordovician sandstones of Ethiopia (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a) with those from Saudi Arabia (this study) in an MDS plot reveals that Upper Ordovician samples from the Wajid area resemble those from northern Ethiopia whereas Upper Ordovician samples from the Tabuk area resemble those from northernmost Ethiopia (Fig. 9). The slight dissimilarity of the age spectra among the glaciogenic sandstones leads to the assumption that a change in provenance occurred during the Late Ordovician (Hirnantian) glaciation. Overall, however, the high similarity of many of the Cambrian–Ordovician age spectra to those of the Upper Ordovician glaciogenic sandstones (Fig. 8a) suggests that no change in provenance occurred with the onset of glaciation. Rather, the glaciers reworked sediment from the underlying Cambrian to Middle Ordovician successions to account for the high maturity of the Upper Ordovician siliciclastics (e.g. Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit and Bussert2018, Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a, b). Thus, large-scale sediment recycling occurred across NE Africa and Arabia during the Hirnantian Gondwana glaciation.

Fig. 9. Non-metric MDS map comparing the detrital zircon age spectra of Upper Ordovician sandstones analysed in this study with published data from Upper Ordovician – Silurian sandstones of Ethiopia (data taken from Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020a). Only ages >500 Ma are used here due to the low reliability of younger ages.

The Carboniferous–Permian samples from Ethiopia plot distinct from those of Saudi Arabia, but with one sample from each of the Wajid and Tabuk areas being close to those from Ethiopia (Fig. 10). Carboniferous–Permian glaciogenic sandstones from Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia show a similar sediment composition, i.e. being feldspar-bearing and containing unstable heavy minerals (Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a, b; Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit and Bussert2018, Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Lünsdorf2020 b). The detritus of the Carboniferous–Permian glaciogenic sandstones of Ethiopia was probably derived from the south, i.e. from basement rocks of the Nubian Shield as inferred from detrital zircon data (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a), and a northward transport direction was inferred by Bussert (Reference Bussert2010) based on the orientation and geometry of palaeolandforms, such as roches moutonnées (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a). In northern Ethiopia, the glaciogenic sandstones were deposited in a large NNE-trending trough in which glacial erosion may have followed and reinforced this preglacial topography (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020 a). Before the opening of the Red Sea, the Arabian Peninsula was attached to NE Africa (Fig. 1b), and thus the Wajid area was in proximity to Ethiopia. Taking all data together, it is suggested that the Carboniferous–Permian glaciogenic sandstones of Saudi Arabia received the majority of their detritus due to erosion of fresh basement rocks likely from the Nubian Shield such as in Ethiopia. On their way to the northeast, only minor amounts of detritus were admixed from the Arabian Shield.

Fig. 10. Non-metric MDS map comparing the detrital zircon age spectra of Devonian and Carboniferous–Permian sandstones analysed in this study with published data from Carboniferous–Permian sandstones of Ethiopia (data taken from Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020a). Only ages >500 Ma are used here due to the low reliability of younger ages.

5.c. Gondwana super-fan system and East African – Arabian zircon province

Based on the similarity of detrital zircon U–Pb age spectra in Palaeozoic sandstones throughout Gondwana, Squire et al. (Reference Squire, Campbell, Allen and Wilson2006) postulated the existence of large sediment fans that brought detritus from the East African Orogen towards the continental margins of Gondwana. Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013) extended the super-fan model to the northern Gondwana margin evaluating detrital zircon age spectra from Cambrian–Ordovician sandstones of Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Israel and Jordan. Sediment belonging to the Gondwana super-fan system contains a prominent amount of 1 Ga detrital zircons besides grains with ages of 0.53–0.75, 1.75–2.15 and 2.5–2.7 Ga (Meinhold et al. Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013). The 1 Ga zircons are a key feature of the Gondwana super-fan system and were likely transported from regions in the centre of the East African Orogen, i.e. from the Mozambique Belt, or from regions of the SE Saharan Metacraton towards the continental margin of Gondwana during the early Palaeozoic. Intensive source area weathering, low sedimentation rates, and reworking during deposition lead to the high mineralogical maturity of the Lower Palaeozoic sediment (see discussion in Bassis et al. Reference Bassis, Hinderer and Meinhold2016 a) containing 1 Ga zircons. According to the Gondwana super-fan model, Saudi Arabia would lie more distal along the sediment path to the northeast. Based on a more extensive detrital zircon dataset including also peri-Gondwana units and using multivariate data analysis, Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019 a) showed the existence of three contrasting provenance end-members in Lower Palaeozoic sedimentary rocks of the former Gondwanan shelf, namely the Avalonian, West African and East African – Arabian zircon provinces (see also Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Kroner, Romer and Rösel2019 b). The East African – Arabian zircon province corresponds to the Gondwana super-fan system of Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013). To test whether the East African – Arabian zircon province is also a feature of the Lower Palaeozoic sandstones of Saudi Arabia, we compared in an MDS plot the newly obtained detrital zircon data from Saudi Arabia (this study) with those from the literature for north and northeast Africa, Israel and Jordan (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Non-metric MDS map comparing the detrital zircon age spectra of Cambrian–Ordovician sandstones analysed in this study with published data from Cambrian–Ordovician sandstones. Only ages >500 Ma are used here due to the low reliability of younger ages. Published data: (1) Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton, Fanning, Frei, Howard, Phillips, Strogen and Whitham2011); (2) Morton et al. (Reference Morton, Whitham, Howard, Fanning, Abutarruma, El Dieb, Elkatarry, Hamhoom, Lüning, Phillips, Thusu, Salem and Abadi2012); (3) Linnemann et al. (Reference Linnemann, Ouzegane, Drareni, Hofmann, Becker, Gärtner and Sagawe2011); (4) Kolodner et al. (Reference Kolodner, Avigad, McWilliams, Wooden, Weissbrod and Feinstein2006); (5) Altumi et al. (Reference Altumi, Elicki, Linnemann, Hofmann, Sagawe and Gärtner2013); (6) Avigad et al. (Reference Avigad, Gerdes, Morag and Bechstädt2012); (7) Lewin et al. (Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020a). Note that the published data are those compiled by Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013) augmented by those from Altumi et al. (Reference Altumi, Elicki, Linnemann, Hofmann, Sagawe and Gärtner2013) and Lewin et al. (Reference Lewin, Meinhold, Hinderer, Dawit, Bussert and Berndt2020a). The orange field outlines the Gondwana super-fan sediments of NE Africa and Arabia, as defined by Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013), which are characterized by detrital zircons with ‘Pan-African’ U–Pb ages accompanied by zircon grains with Tonian–Stenian (1 Ga) and minor older ages. Sediments with such ages correspond to the East African – Arabian zircon province of Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019a).

The majority of the Lower Palaeozoic samples from Saudi Arabia reveal a high similarity to samples from Libya, Israel, Jordan and Ethiopia (Fig. 11). This suggests that the Gondwana super-fan system was extensive and supplied detritus with a signature of an East African – Arabian zircon province also to the Lower Palaeozoic succession of Saudi Arabia (Fig. 12). The Algerian samples are not part of the cluster. In addition, some Cambrian and Lower Ordovician samples from Libya, Israel and Jordan are not part of the cluster. This is because the Gondwana super-fan system with an East African – Arabian zircon province seems to have been active at different times across NE Africa and Arabia, with the main phase of activity starting at some point between the Late Cambrian and late Middle Ordovician (Meinhold et al. Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013).

Fig. 12. Palaeogeographic reconstruction of Gondwana (480 Ma) modified after Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner, Romer and Rösel2019b) showing the main zircon provinces recognized in Cambrian–Ordovician siliciclastic sediments of northern Gondwana and its periphery. The East African – Arabian zircon province defined by Stephan et al. (Reference Stephan, Kroner and Romer2019a) corresponds to the zircon province of the Gondwana super-fan system of Meinhold et al. (Reference Meinhold, Morton and Avigad2013). According to the detrital zircon U–Pb ages from Palaeozoic sandstones of Saudi Arabia (this study), the East African – Arabian zircon province can be extended to the central and southern Arabian Peninsula. White arrows show main sediment transport direction.

As discussed in Section 5.a, the Sa’al metamorphic complex on the Sinai Peninsula comprises 1 Ga basement rocks (Be’eri-Shlevin et al. Reference Be’eri-Shlevin, Eyal, Eyal, Whitehouse and Litvinovsky2012) and it is in proximity to the study area, at least to the Tabuk area. However, sediment supply from the Sinai basement to the Ordovician succession of Saudi Arabia is rather unlikely taking into account the roundness of the detrital zircon grains (this study) and the palaeocurrent data that point toward a southerly provenance (Dabbagh & Rogers, Reference Dabbagh and Rogers1983; Stump & van der Eem, Reference Stump and van der Eem1995; Babalola, Reference Babalola1999; Hussain et al. Reference Hussain, Babalola and Hariri2000). For example, palaeocurrents of Upper Ordovician sandstones from the southeastern Tabuk area show sediment transport away from the Arabian Shield toward the northeast (Clark-Lowes, Reference Clark-Lowes2005).

6. Conclusions

The erosion history of the East African Orogen and sediment recycling in northern Gondwana during the Palaeozoic have been topics of much debate. Our new detrital zircon U–Pb ages from 24 sandstone samples from the Cambrian to Permian succession of Saudi Arabia provide new insights into these topics.

Five main zircon age populations have been identified in varying amounts, with age peaks at 625 Ma, 775 Ma, 980 Ma, 1840 Ma and 2480 Ma. Igneous rocks are the primary source of these grains, as most of the zircons show undisturbed oscillatory zoning and some also show regrowth features in the CL images. Ediacaran to middle Tonian zircon grains are likely derived from igneous rocks of the Arabian–Nubian Shield. Palaeoproterozoic and Archaean grains may be xenocrystic zircons. However, this likely only accounts for a small number of grains. Recycling from older terrigenous sediment is possible. A primary derivation from Palaeoproterozoic and Archaean basement is also likely, as meta-igneous rocks of such age occur in the vicinity of the study area. A minor amount (4 %) of the detrital zircons show Palaeozoic (340–541 Ma) ages. Early Palaeozoic zircons are likely derived from Cambrian and Ordovician post-orogenic igneous rocks, as present in the Arabian–Nubian Shield and to the south. Late Palaeozoic zircons may come from within-plate, anorogenic igneous rocks, as known from northern Arabia.

It is worth emphasizing that the zircon grains with up to Eoarchaean (3.6–4.0 Ga) ages are the oldest zircons yet presented from Arabia and its vicinity. It can be speculated that these grains represent xenocrystic cores originally derived from igneous rocks of the Arabian–Nubian Shield. However, such old ages have not yet been described from basement rocks of NE Africa and Arabia, and thus their origin is enigmatic. Tonian–Stenian (900 to <1200 Ma) zircons are present in varying amounts in all of the samples and are a feature of terrigenous sediment belonging to the Gondwana super-fan system and the East African – Arabian zircon province, respectively, in early Palaeozoic time. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) reveals similarities between detrital zircon age spectra from Ordovician sandstones of Saudi Arabia and time-equivalent successions of Ethiopia, Libya, Israel and Jordan. Thus, the Gondwana super-fan system with an East African – Arabian zircon province had a larger size than previously thought, as it also reached the Arabian Peninsula during the early Palaeozoic. Glaciogenic sandstones from Saudi Arabia related to the Late Ordovician (Hirnantian) Gondwana glaciation resemble time-equivalent successions from Ethiopia, suggesting prominent sediment transport and recycling with similar provenance. Besides that, MDS shows dissimilarities between detrital zircon spectra from Devonian and Carboniferous–Permian sandstones of Saudi Arabia, suggesting a prominent provenance change with the onset of the late Palaeozoic Gondwana glaciation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG grant numbers HI 643/13-1, ME 3882/4-1). We are grateful for the logistical support of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and Dornier Consulting International (DCo) GmbH in Riyadh. A special thanks goes to Randolf Rausch and the entire GIZ/DCo staff for their assistance and support during the field campaign and their interest in this study. We are grateful to Andreas Kronz for providing access to the electron microprobe for cathodoluminescence imaging, and to Beate Schmitte for assistance at the laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry facility. Careful and constructive reviews by Victoria Pease and an anonymous reviewer are greatly appreciated.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756820000576