Introduction

During the past decade, the trend of global displacement has been growing (UNHCR, Reference UNHCR2020). In 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) estimated that more than 11 million people have been displaced throughout the year, and the proportion of this population has been continued to rise, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and closure of borders (UNHCR, Reference UNHCR2020). Although refugees (people who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution, are forced to escape from his or her country) and asylum seekers (people seeking protection from persecution or serious harm in a country other than their own) are defined in different ways (UNHCR, Reference UNHCR2020), both groups may have been forced to face various stressors, such as persecution, violence, torture, detention, and the loss of homes and livelihoods. Such traumatic events may result in persistent mental health problems and overall decreased functioning (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009; Marquez, Reference Marquez2016).

During the last years, several studies have examined the prevalence of mental disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. However, the resulting prevalence rates in this population present great variability (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005; Porter and Haslam, Reference Porter and Haslam2005; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015; Foo et al., Reference Foo, Tam, Ho, Tran, Nguyen, McIntyre and Ho2018; Morina et al., Reference Morina, Akhtar, Barth and Schnyder2018; Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019; Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020), ranging from 5% (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005) to 80% (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015) for depression, from 4% (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019) to 88% (Morina et al., Reference Morina, Akhtar, Barth and Schnyder2018) for PTSD, and from 1.5% (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020) to 2% (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005) for psychosis. A systematic review on the prevalence of serious mental disorders in refugees resettled in high-income western countries reported weighted average rates of 5% for major depressive disorder (MDD), 9% for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 2% for psychotic disorders (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005). A meta-analysis among refugees and asylum seekers residing outside their country of origin reported a prevalence of 31.5% for PTSD, of 31.5% for depression, and 1.5% for psychosis (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020). Another meta-analysis that examined the prevalence of mental disorders in conflict settings showed estimated rates of 22.1% for any mental disorder (13% for depression and 4% for PTSD) (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). The variability across studies could be explained by differences in the origins and background of the analysed populations, the sample size, the sampling methods, and the diagnostic tools used (e.g. self-report, semi-structured or structured clinical interview) (Westermeyer and Janca, Reference Westermeyer and Janca1997; de Jong et al., Reference de Jong, Komproe and Van Ommeren2003; Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018; Giacco and Priebe, Reference Giacco and Priebe2018; Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). Furthermore, the nature of the displacement, the context of the emergency, as well as the aspects of the host country/environment are additional aspects to consider in the variability of these studies (Giacco and Priebe, Reference Giacco and Priebe2018).

Many epidemiological studies use self-report instruments to estimate the prevalence of mental disorders in refugees because they are easily administered and cost effective. However, such instruments overestimate prevalence rates considerably (Domken et al., Reference Domken, Scott and Kelly1994; Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009). In fact, self-report instruments have been shown to overestimate true PTSD-rates by a factor of about 3.5 (Engelhard et al., Reference Engelhard, van den Hout, Weerts, Arntz, Hox and McNally2007). Similar results have been also shown in depression studies (Domken et al., Reference Domken, Scott and Kelly1994; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009; Krebber et al., Reference Krebber, Buffart, Kleijn, Riepma, de Bree, Leemans, Becker, Brug, van Straten, Cuijpers and Verdonck-de Leeuw2014). One of the reasons is that many self-report instruments are designed for quickly picking-up mental disorders while minimising false negatives, therefore cut-offs are set with high sensitivity. Therefore, they identify more patients who may have a mental disorder than those diagnosed with clinician-administered interviews (Thombs et al., Reference Thombs, Kwakkenbos, Levis and Benedetti2018). Another reason could be that self-report tools usually do not take functional impairment due to symptoms into account (McKnight and Kashdan, Reference McKnight and Kashdan2009). Besides, translations of existing self-report instruments may not adequately measure psychiatric symptoms across cultures (Hunt and Bhopal, Reference Hunt and Bhopal2004). Finally, overestimation may occur as a consequence of the so-called over-endorsement bias, the tendency of respondents to generously claim different types of symptoms on a checklist (Kroenke, Reference Kroenke2001). Thus, more rigorous instruments, such as clinical diagnostic interviews, are more appropriate to estimate the prevalence of mental health disorders in refugees and asylum seekers (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009). In addition, clinicians' experience in using structured interviews can increase the reliability of symptoms measurement and psychiatric diagnoses even among samples with different cultural backgrounds (Alarcon et al., Reference Alarcon, Westermeyer, Foulks and Ruiz1999; Aboraya et al., Reference Aboraya, Rankin, France, El-Missiry and John2006). Nevertheless, among the structured and semi-structured interviews there may also be some differences in accuracy. For example, studies have shown that the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview – MINI, which has been designed as a briefer and quicker diagnostic screen than other interviews (Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Harnett Sheehan, Janavs, Weiller, Keskiner, Schinka, Knapp, Sheehan and Dunbar1997) identified more people as depressed than the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – CIDI, and the Structured Clinical Interview – SCID (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Benedetti, Riehm, Saadat, Levis, Azar, Rice, Chiovitti, Sanchez, Cuijpers, Gilbody, Ioannidis, Kloda, McMillan, Patten, Shrier, Steele, Ziegelstein, Akena, Arroll, Ayalon, Baradaran, Baron, Beraldi, Bombardier, Butterworth, Carter, Chagas, Chan, Cholera, Chowdhary, Clover, Conwell, de Man-van Ginkel, Delgadillo, Fann, Fischer, Fischler, Fung, Gelaye, Goodyear-Smith, Greeno, Hall, Hambridge, Harrison, Hegerl, Hides, Hobfoll, Hudson, Hyphantis, Inagaki, Ismail, Jette, Khamseh, Kiely, Lamers, Liu, Lotrakul, Loureiro, Lowe, Marsh, McGuire, Mohd Sidik, Munhoz, Muramatsu, Osorio, Patel, Pence, Persoons, Picardi, Rooney, Santos, Shaaban, Sidebottom, Simning, Stafford, Sung, Tan, Turner, van der Feltz-Cornelis, van Weert, Vohringer, White, Whooley, Winkley, Yamada, Zhang and Thombs2018; Levis et al., Reference Levis, McMillan, Sun, He, Rice, Krishnan, Wu, Azar, Sanchez, Chiovitti, Bhandari, Neupane, Saadat, Riehm, Imran, Boruff, Cuijpers, Gilbody, Ioannidis, Kloda, Patten, Shrier, Ziegelstein, Comeau, Mitchell, Tonelli, Vigod, Aceti, Alvarado, Alvarado-Esquivel, Bakare, Barnes, Beck, Bindt, Boyce, Bunevicius, Couto, Chaudron, Correa, de Figueiredo, Eapen, Fernandes, Figueiredo, Fisher, Garcia-Esteve, Giardinelli, Helle, Howard, Khalifa, Kohlhoff, Kusminskas, Kozinszky, Lelli, Leonardou, Lewis, Maes, Meuti, Nakic Rados, Navarro Garcia, Nishi, Okitundu Luwa, Robertson-Blackmore, Rochat, Rowe, Siu, Skalkidou, Stein, Stewart, Su, Sundstrom-Poromaa, Tadinac, Tandon, Tendais, Thiagayson, Toreki, Torres-Gimenez, Tran, Trevillion, Turner, Vega-Dienstmaier, Wynter, Yonkers, Benedetti and Thombs2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Levis, Ioannidis, Benedetti, Thombs and Collaboration2021).

In the present study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of diagnoses of serious mental disorders [MDD, PTSD, bipolar disorder (BPD), and psychosis] in refugees and asylum seekers from conflict-affected areas. Serious mental disorders are conditions resulting in serious functional impairment, which interferes with major life activities (NIH, Reference NIH2019). Other definitions (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Powell and Strathdee1997) take into account the duration and the disability they produce, for example in terms of the disability they are associated with. Within the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, the top-three mental disorders associated with the highest level of disability are MDD, BPD and psychosis (Kronenberg et al., Reference Kronenberg, Doran, Goddard, Kendrick, Gilbody, Dare, Aylott and Jacobs2017; James et al., Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdela, Abdelalim, Abdollahpour, Abdulkader, Abebe, Abera, Abil, Abraha, Abu-Raddad, Abu-Rmeileh, Accrombessi, Acharya, Acharya, Ackerman, Adamu, Adebayo, Adekanmbi, Adetokunboh, Adib, Adsuar, Afanvi, Afarideh, Afshin, Agarwal, Agesa, Aggarwal, Aghayan, Agrawal, Ahmadi, Ahmadi, Ahmadieh, Ahmed, Aichour, Aichour, Aichour, Akinyemiju, Akseer, Al-Aly, Al-Eyadhy, Al-Mekhlafi, Al-Raddadi, Alahdab, Alam, Alam, Alashi, Alavian, Alene, Alijanzadeh, Alizadeh-Navaei, Aljunid, Alkerwi, Alla, Allebeck, Alouani, Altirkawi, Alvis-Guzman, Amare, Aminde, Ammar, Amoako, Anber, Andrei, Androudi, Animut, Anjomshoa, Ansha, Antonio, Anwari, Arabloo, Arauz, Aremu, Ariani, Armoon, Ärnlöv, Arora, Artaman, Aryal, Asayesh, Asghar, Ataro, Atre, Ausloos, Avila-Burgos, Avokpaho, Awasthi, Ayala Quintanilla, Ayer, Azzopardi, Babazadeh, Badali, Badawi, Bali, Ballesteros, Ballew, Banach, Banoub, Banstola, Barac, Barboza, Barker-Collo, Bärnighausen, Barrero, Baune, Bazargan-Hejazi, Bedi, Beghi, Behzadifar, Behzadifar, Béjot, Belachew, Belay, Bell, Bello, Bensenor, Bernabe, Bernstein, Beuran, Beyranvand, Bhala, Bhattarai, Bhaumik, Bhutta, Biadgo, Bijani, Bikbov, Bilano, Bililign, Bin Sayeed, Bisanzio, Blacker, Blyth, Bou-Orm, Boufous, Bourne, Brady, Brainin, Brant, Brazinova, Breitborde, Brenner, Briant, Briggs, Briko, Britton, Brugha, Buchbinder, Busse, Butt, Cahuana-Hurtado, Cano, Cárdenas, Carrero, Carter, Carvalho, Castañeda-Orjuela, Castillo Rivas, Castro, Catalá-López, Cercy, Cerin, Chaiah, Chang, Chang, Chang, Charlson, Chattopadhyay, Chattu, Chaturvedi, Chiang, Chin, Chitheer, Choi, Chowdhury, Christensen, Christopher, Cicuttini, Ciobanu, Cirillo, Claro, Collado-Mateo, Cooper, Coresh, Cortesi, Cortinovis, Costa, Cousin, Criqui, Cromwell, Cross, Crump, Dadi, Dandona, Dandona, Dargan, Daryani, Das Gupta, Das Neves, Dasa, Davey, Davis, Davitoiu, De Courten, De La Hoz, De Leo, De Neve, Degefa, Degenhardt, Deiparine, Dellavalle, Demoz, Deribe, Dervenis, Des Jarlais, Dessie, Dey, Dharmaratne, Dinberu, Dirac, Djalalinia, Doan, Dokova, Doku, Dorsey, Doyle, Driscoll, Dubey, Dubljanin, Duken, Duncan, Duraes, Ebrahimi, Ebrahimpour, Echko, Edvardsson, Effiong, Ehrlich, El Bcheraoui, El Sayed Zaki, El-Khatib, Elkout, Elyazar, Enayati, Endries, Er, Erskine, Eshrati, Eskandarieh, Esteghamati, Esteghamati, Fakhim, Fallah Omrani, Faramarzi, Fareed, Farhadi, Farid, Farinha, Farioli, Faro, Farvid, Farzadfar, Feigin, Fentahun, Fereshtehnejad, Fernandes, Fernandes, Ferrari, Feyissa, Filip, Fischer, Fitzmaurice, Foigt, Foreman, Fox, Frank, Fukumoto, Fullman, Fürst, Furtado, Futran, Gall, Ganji, Gankpe, Garcia-Basteiro, Gardner, Gebre, Gebremedhin, Gebremichael, Gelano, Geleijnse, Genova-Maleras, Geramo, Gething, Gezae, Ghadiri, Ghasemi Falavarjani, Ghasemi-Kasman, Ghimire, Ghosh, Ghoshal, Giampaoli, Gill, Gill, Ginawi, Giussani, Gnedovskaya, Goldberg, Goli, Gómez-Dantés, Gona, Gopalani, Gorman, Goulart, Goulart, Grada, Grams, Grosso, Gugnani, Guo, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gyawali, Haagsma, Hachinski, Hafezi-Nejad, Haghparast Bidgoli, Hagos, Hailu, Haj-Mirzaian, Haj-Mirzaian, Hamadeh, Hamidi, Handal, Hankey, Hao, Harb, Harikrishnan, Haro, Hasan, Hassankhani, Hassen, Havmoeller, Hawley, Hay, Hay, Hedayatizadeh-Omran, Heibati, Hendrie, Henok, Herteliu, Heydarpour, Hibstu, Hoang, Hoek, Hoffman, Hole, Homaie Rad, Hoogar, Hosgood, Hosseini, Hosseinzadeh, Hostiuc, Hostiuc, Hotez, Hoy, Hsairi, Htet, Hu, Huang, Huynh, Iburg, Ikeda, Ileanu, Ilesanmi, Iqbal, Irvani, Irvine, Islam, Islami, Jacobsen, Jahangiry, Jahanmehr, Jain, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, Jayatilleke, Jeemon, Jha, Jha, Ji, Johnson, Jonas, Jozwiak, Jungari, Jürisson, Kabir, Kadel, Kahsay, Kalani, Kanchan, Karami, Karami Matin, Karch, Karema, Karimi, Karimi, Kasaeian, Kassa, Kassa, Kassa, Kassebaum, Katikireddi, Kawakami, Karyani, Keighobadi, Keiyoro, Kemmer, Kemp, Kengne, Keren, Khader, Khafaei, Khafaie, Khajavi, Khalil, Khan, Khan, Khan, Khang, Khazaei, Khoja, Khosravi, Khosravi, Kiadaliri, Kiirithio, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kimokoti, Kinfu, Kisa, Kissimova-Skarbek, Kivimäki, Knudsen, Kocarnik, Kochhar, Kokubo, Kolola, Kopec, Kosen, Kotsakis, Koul, Koyanagi, Kravchenko, Krishan, Krohn, Kuate Defo, Kucuk Bicer, Kumar, Kumar, Kyu, Lad, Lad, Lafranconi, Lalloo, Lallukka, Lami, Lansingh, Latifi, Lau, Lazarus, Leasher, Ledesma, Lee, Leigh, Leung, Levi, Lewycka, Li, Li, Liao, Liben, Lim, Lim, Liu, Lodha, Looker, Lopez, Lorkowski, Lotufo, Low, Lozano, Lucas, Lucchesi, Lunevicius, Lyons, Ma, Macarayan, Mackay, Madotto, Magdy Abd El Razek, Magdy Abd El Razek, Maghavani, Mahotra, Mai, Majdan, Majdzadeh, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Malta, Mamun, Manda, Manguerra, Manhertz, Mansournia, Mantovani, Mapoma, Maravilla, Marcenes, Marks, Martins-Melo, Martopullo, März, Marzan, Mashamba-Thompson, Massenburg, Mathur, Matsushita, Maulik, Mazidi, McAlinden, McGrath, McKee, Mehndiratta, Mehrotra, Mehta, Mehta, Mejia-Rodriguez, Mekonen, Melese, Melku, Meltzer, Memiah, Memish, Mendoza, Mengistu, Mengistu, Mensah, Mereta, Meretoja, Meretoja, Mestrovic, Mezerji, Miazgowski, Miazgowski, Millear, Miller, Miltz, Mini, Mirarefin, Mirrakhimov, Misganaw, Mitchell, Mitiku, Moazen, Mohajer, Mohammad, Mohammadifard, Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, Mohammed, Mohammed, Mohebi, Moitra, Mokdad, Molokhia, Monasta, Moodley, Moosazadeh, Moradi, Moradi-Lakeh, Moradinazar, Moraga, Morawska, Moreno Velásquez, Morgado-Da-Costa, Morrison, Moschos, Mountjoy-Venning, Mousavi, Mruts, Muche, Muchie, Mueller, Muhammed, Mukhopadhyay, Muller, Mumford, Murhekar, Musa, Musa, Mustafa, Nabhan, Nagata, Naghavi, Naheed, Nahvijou, Naik, Naik, Najafi, Naldi, Nam, Nangia, Nansseu, Nascimento, Natarajan, Neamati, Negoi, Negoi, Neupane, Newton, Ngunjiri, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nichols, Ningrum, Nixon, Nolutshungu, Nomura, Norheim, Noroozi, Norrving, Noubiap, Nouri, Nourollahpour Shiadeh, Nowroozi, Nsoesie, Nyasulu, Odell, Ofori-Asenso, Ogbo, Oh, Oladimeji, Olagunju, Olagunju, Olivares, Olsen, Olusanya, Ong, Ong, Oren, Ortiz, Ota, Otstavnov, Øverland, Owolabi, Pacella, Pakpour, Pana, Panda-Jonas, Parisi, Park, Parry, Patel, Pati, Patil, Patle, Patton, Paturi, Paulson, Pearce, Pereira, Perico, Pesudovs, Pham, Phillips, Pigott, Pillay, Piradov, Pirsaheb, Pishgar, Plana-Ripoll, Plass, Polinder, Popova, Postma, Pourshams, Poustchi, Prabhakaran, Prakash, Prakash, Purcell, Purwar, Qorbani, Quistberg, Radfar, Rafay, Rafiei, Rahim, Rahimi, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rai, Rajati, Ram, Ranjan, Ranta, Rao, Rawaf, Rawaf, Reddy, Reiner, Reinig, Reitsma, Remuzzi, Renzaho, Resnikoff, Rezaei, Rezai, Ribeiro, Roberts, Robinson, Roever, Ronfani, Roshandel, Rostami, Roth, Roy, Rubagotti, Sachdev, Sadat, Saddik, Sadeghi, Saeedi Moghaddam, Safari, Safari, Safari-Faramani, Safdarian, Safi, Safiri, Sagar, Sahebkar, Sahraian, Sajadi, Salam, Salama, Salamati, Saleem, Saleem, Salimi, Salomon, Salvi, Salz, Samy, Sanabria, Sang, Santomauro, Santos, Santos, Santric Milicevic, Sao Jose, Sardana, Sarker, Sarrafzadegan, Sartorius, Sarvi, Sathian, Satpathy, Sawant, Sawhney, Saxena, Saylan, Schaeffner, Schmidt, Schneider, Schöttker, Schwebel, Schwendicke, Scott, Sekerija, Sepanlou, Serván-Mori, Seyedmousavi, Shabaninejad, Shafieesabet, Shahbazi, Shaheen, Shaikh, Shams-Beyranvand, Shamsi, Shamsizadeh, Sharafi, Sharafi, Sharif, Sharif-Alhoseini, Sharma, Sharma, She, Sheikh, Shi, Shibuya, Shigematsu, Shiri, Shirkoohi, Shishani, Shiue, Shokraneh, Shoman, Shrime, Si, Siabani, Siddiqi, Sigfusdottir, Sigurvinsdottir, Silva, Silveira, Singam, Singh, Singh, Singh, Sinha, Skiadaresi, Slepak, Sliwa, Smith, Smith, Soares Filho, Sobaih, Sobhani, Sobngwi, Soneji, Soofi, Soosaraei, Sorensen, Soriano, Soyiri, Sposato, Sreeramareddy, Srinivasan, Stanaway, Stein, Steiner, Steiner, Stokes, Stovner, Subart, Sudaryanto, Sufiyan, Sunguya, Sur, Sutradhar, Sykes, Sylte, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Tadakamadla, Tadesse, Tandon, Tassew, Tavakkoli, Taveira, Taylor, Tehrani-Banihashemi, Tekalign, Tekelemedhin, Tekle, Temesgen, Temsah, Temsah, Terkawi, Teweldemedhin, Thankappan, Thomas, Tilahun, To, Tonelli, Topor-Madry, Topouzis, Torre, Tortajada-Girbés, Touvier, Tovani-Palone, Towbin, Tran, Tran, Troeger, Truelsen, Tsilimbaris, Tsoi, Tudor Car, Tuzcu, Ukwaja, Ullah, Undurraga, Unutzer, Updike, Usman, Uthman, Vaduganathan, Vaezi, Valdez, Varughese, Vasankari, Venketasubramanian, Villafaina, Violante, Vladimirov, Vlassov, Vollset, Vosoughi, Vujcic, Wagnew, Waheed, Waller, Wang, Wang, Weiderpass, Weintraub, Weiss, Weldegebreal, Weldegwergs, Werdecker, West, Whiteford, Widecka, Wijeratne, Wilner, Wilson, Winkler, Wiyeh, Wiysonge, Wolfe, Woolf, Wu, Wu, Wyper, Xavier, Xu, Yadgir, Yadollahpour, Yahyazadeh Jabbari, Yamada, Yan, Yano, Yaseri, Yasin, Yeshaneh, Yimer, Yip, Yisma, Yonemoto, Yoon, Yotebieng, Younis, Yousefifard, Yu, Zadnik, Zaidi, Zaman, Zamani, Zare, Zeleke, Zenebe, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou, Zodpey, Zucker, Vos and Murray2018). Although not included in the GBD, PTSD is particularly relevant for refugees and asylum seekers since refugees may be exposed to multiple traumatic events, including interpersonal violence that may cause severe disability (Palic et al., Reference Palic, Zerach, Shevlin, Zeligman, Elklit and Solomon2016).

Similar to previous studies (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005; Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020), we included only studies that employed diagnostic interviews. Further, our study differs from previous studies in that we were able to include a larger number of studies than before since the number of studies increased during the past years. In addition, we were able to examine the prevalence of less common disorders such as BPD. Finally, due to the increased number of included studies, we could perform additional subgroup analyses, such as comparing the prevalence of serious mental disorders between refugees resettled in low-middle-income v. high-income countries, and among different kind of population sample (convenience samples v. probability-based samples).

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

We report our meta-analysis according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org) (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2009) (see online Supplementary materials).

The present study was registered in PROSPERO on 5th December 2018 under the number: CRD42018111778.

A comprehensive search was performed in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase.com and APA PsycInfo (via Ebsco) from inception to June 4, 2020, by a medical librarian. Search terms included controlled terms (MeSH in PubMed, Emtree in Embase and PsycINFO thesaurus terms) as well as free text terms. The following terms were used (including synonyms and closely related words) as index terms or free-text words: ‘refugees’ and ‘mental illnesses’. A search filter was used to limit the results to adults. The search was performed without date or language restrictions. Duplicate articles were excluded. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the online Supplementary materials.

Studies were considered eligible for this meta-analysis if they examined (a) the prevalence of serious mental disorders (MDD, PTSD, BPD, and psychosis), (b) in an adult (⩾18 years) population of refugees and asylum seekers who had to cross their country borders, (c) according to the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III, IV, or 5) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD 9 or10) (d) assessed with a structured or semi-structured clinical interview, such as the Structured Clinical Interview – SCID, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview – MINI, or Composite International Diagnostic Interview – CIDI. No cut-off has been considered to evaluate the diagnosis' severity. Disorders have been evaluated serious according with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIH) and GBD considerations (Kronenberg et al., Reference Kronenberg, Doran, Goddard, Kendrick, Gilbody, Dare, Aylott and Jacobs2017; James et al., Reference James, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdela, Abdelalim, Abdollahpour, Abdulkader, Abebe, Abera, Abil, Abraha, Abu-Raddad, Abu-Rmeileh, Accrombessi, Acharya, Acharya, Ackerman, Adamu, Adebayo, Adekanmbi, Adetokunboh, Adib, Adsuar, Afanvi, Afarideh, Afshin, Agarwal, Agesa, Aggarwal, Aghayan, Agrawal, Ahmadi, Ahmadi, Ahmadieh, Ahmed, Aichour, Aichour, Aichour, Akinyemiju, Akseer, Al-Aly, Al-Eyadhy, Al-Mekhlafi, Al-Raddadi, Alahdab, Alam, Alam, Alashi, Alavian, Alene, Alijanzadeh, Alizadeh-Navaei, Aljunid, Alkerwi, Alla, Allebeck, Alouani, Altirkawi, Alvis-Guzman, Amare, Aminde, Ammar, Amoako, Anber, Andrei, Androudi, Animut, Anjomshoa, Ansha, Antonio, Anwari, Arabloo, Arauz, Aremu, Ariani, Armoon, Ärnlöv, Arora, Artaman, Aryal, Asayesh, Asghar, Ataro, Atre, Ausloos, Avila-Burgos, Avokpaho, Awasthi, Ayala Quintanilla, Ayer, Azzopardi, Babazadeh, Badali, Badawi, Bali, Ballesteros, Ballew, Banach, Banoub, Banstola, Barac, Barboza, Barker-Collo, Bärnighausen, Barrero, Baune, Bazargan-Hejazi, Bedi, Beghi, Behzadifar, Behzadifar, Béjot, Belachew, Belay, Bell, Bello, Bensenor, Bernabe, Bernstein, Beuran, Beyranvand, Bhala, Bhattarai, Bhaumik, Bhutta, Biadgo, Bijani, Bikbov, Bilano, Bililign, Bin Sayeed, Bisanzio, Blacker, Blyth, Bou-Orm, Boufous, Bourne, Brady, Brainin, Brant, Brazinova, Breitborde, Brenner, Briant, Briggs, Briko, Britton, Brugha, Buchbinder, Busse, Butt, Cahuana-Hurtado, Cano, Cárdenas, Carrero, Carter, Carvalho, Castañeda-Orjuela, Castillo Rivas, Castro, Catalá-López, Cercy, Cerin, Chaiah, Chang, Chang, Chang, Charlson, Chattopadhyay, Chattu, Chaturvedi, Chiang, Chin, Chitheer, Choi, Chowdhury, Christensen, Christopher, Cicuttini, Ciobanu, Cirillo, Claro, Collado-Mateo, Cooper, Coresh, Cortesi, Cortinovis, Costa, Cousin, Criqui, Cromwell, Cross, Crump, Dadi, Dandona, Dandona, Dargan, Daryani, Das Gupta, Das Neves, Dasa, Davey, Davis, Davitoiu, De Courten, De La Hoz, De Leo, De Neve, Degefa, Degenhardt, Deiparine, Dellavalle, Demoz, Deribe, Dervenis, Des Jarlais, Dessie, Dey, Dharmaratne, Dinberu, Dirac, Djalalinia, Doan, Dokova, Doku, Dorsey, Doyle, Driscoll, Dubey, Dubljanin, Duken, Duncan, Duraes, Ebrahimi, Ebrahimpour, Echko, Edvardsson, Effiong, Ehrlich, El Bcheraoui, El Sayed Zaki, El-Khatib, Elkout, Elyazar, Enayati, Endries, Er, Erskine, Eshrati, Eskandarieh, Esteghamati, Esteghamati, Fakhim, Fallah Omrani, Faramarzi, Fareed, Farhadi, Farid, Farinha, Farioli, Faro, Farvid, Farzadfar, Feigin, Fentahun, Fereshtehnejad, Fernandes, Fernandes, Ferrari, Feyissa, Filip, Fischer, Fitzmaurice, Foigt, Foreman, Fox, Frank, Fukumoto, Fullman, Fürst, Furtado, Futran, Gall, Ganji, Gankpe, Garcia-Basteiro, Gardner, Gebre, Gebremedhin, Gebremichael, Gelano, Geleijnse, Genova-Maleras, Geramo, Gething, Gezae, Ghadiri, Ghasemi Falavarjani, Ghasemi-Kasman, Ghimire, Ghosh, Ghoshal, Giampaoli, Gill, Gill, Ginawi, Giussani, Gnedovskaya, Goldberg, Goli, Gómez-Dantés, Gona, Gopalani, Gorman, Goulart, Goulart, Grada, Grams, Grosso, Gugnani, Guo, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gupta, Gyawali, Haagsma, Hachinski, Hafezi-Nejad, Haghparast Bidgoli, Hagos, Hailu, Haj-Mirzaian, Haj-Mirzaian, Hamadeh, Hamidi, Handal, Hankey, Hao, Harb, Harikrishnan, Haro, Hasan, Hassankhani, Hassen, Havmoeller, Hawley, Hay, Hay, Hedayatizadeh-Omran, Heibati, Hendrie, Henok, Herteliu, Heydarpour, Hibstu, Hoang, Hoek, Hoffman, Hole, Homaie Rad, Hoogar, Hosgood, Hosseini, Hosseinzadeh, Hostiuc, Hostiuc, Hotez, Hoy, Hsairi, Htet, Hu, Huang, Huynh, Iburg, Ikeda, Ileanu, Ilesanmi, Iqbal, Irvani, Irvine, Islam, Islami, Jacobsen, Jahangiry, Jahanmehr, Jain, Jakovljevic, Javanbakht, Jayatilleke, Jeemon, Jha, Jha, Ji, Johnson, Jonas, Jozwiak, Jungari, Jürisson, Kabir, Kadel, Kahsay, Kalani, Kanchan, Karami, Karami Matin, Karch, Karema, Karimi, Karimi, Kasaeian, Kassa, Kassa, Kassa, Kassebaum, Katikireddi, Kawakami, Karyani, Keighobadi, Keiyoro, Kemmer, Kemp, Kengne, Keren, Khader, Khafaei, Khafaie, Khajavi, Khalil, Khan, Khan, Khan, Khang, Khazaei, Khoja, Khosravi, Khosravi, Kiadaliri, Kiirithio, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kimokoti, Kinfu, Kisa, Kissimova-Skarbek, Kivimäki, Knudsen, Kocarnik, Kochhar, Kokubo, Kolola, Kopec, Kosen, Kotsakis, Koul, Koyanagi, Kravchenko, Krishan, Krohn, Kuate Defo, Kucuk Bicer, Kumar, Kumar, Kyu, Lad, Lad, Lafranconi, Lalloo, Lallukka, Lami, Lansingh, Latifi, Lau, Lazarus, Leasher, Ledesma, Lee, Leigh, Leung, Levi, Lewycka, Li, Li, Liao, Liben, Lim, Lim, Liu, Lodha, Looker, Lopez, Lorkowski, Lotufo, Low, Lozano, Lucas, Lucchesi, Lunevicius, Lyons, Ma, Macarayan, Mackay, Madotto, Magdy Abd El Razek, Magdy Abd El Razek, Maghavani, Mahotra, Mai, Majdan, Majdzadeh, Majeed, Malekzadeh, Malta, Mamun, Manda, Manguerra, Manhertz, Mansournia, Mantovani, Mapoma, Maravilla, Marcenes, Marks, Martins-Melo, Martopullo, März, Marzan, Mashamba-Thompson, Massenburg, Mathur, Matsushita, Maulik, Mazidi, McAlinden, McGrath, McKee, Mehndiratta, Mehrotra, Mehta, Mehta, Mejia-Rodriguez, Mekonen, Melese, Melku, Meltzer, Memiah, Memish, Mendoza, Mengistu, Mengistu, Mensah, Mereta, Meretoja, Meretoja, Mestrovic, Mezerji, Miazgowski, Miazgowski, Millear, Miller, Miltz, Mini, Mirarefin, Mirrakhimov, Misganaw, Mitchell, Mitiku, Moazen, Mohajer, Mohammad, Mohammadifard, Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, Mohammed, Mohammed, Mohebi, Moitra, Mokdad, Molokhia, Monasta, Moodley, Moosazadeh, Moradi, Moradi-Lakeh, Moradinazar, Moraga, Morawska, Moreno Velásquez, Morgado-Da-Costa, Morrison, Moschos, Mountjoy-Venning, Mousavi, Mruts, Muche, Muchie, Mueller, Muhammed, Mukhopadhyay, Muller, Mumford, Murhekar, Musa, Musa, Mustafa, Nabhan, Nagata, Naghavi, Naheed, Nahvijou, Naik, Naik, Najafi, Naldi, Nam, Nangia, Nansseu, Nascimento, Natarajan, Neamati, Negoi, Negoi, Neupane, Newton, Ngunjiri, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen, Nichols, Ningrum, Nixon, Nolutshungu, Nomura, Norheim, Noroozi, Norrving, Noubiap, Nouri, Nourollahpour Shiadeh, Nowroozi, Nsoesie, Nyasulu, Odell, Ofori-Asenso, Ogbo, Oh, Oladimeji, Olagunju, Olagunju, Olivares, Olsen, Olusanya, Ong, Ong, Oren, Ortiz, Ota, Otstavnov, Øverland, Owolabi, Pacella, Pakpour, Pana, Panda-Jonas, Parisi, Park, Parry, Patel, Pati, Patil, Patle, Patton, Paturi, Paulson, Pearce, Pereira, Perico, Pesudovs, Pham, Phillips, Pigott, Pillay, Piradov, Pirsaheb, Pishgar, Plana-Ripoll, Plass, Polinder, Popova, Postma, Pourshams, Poustchi, Prabhakaran, Prakash, Prakash, Purcell, Purwar, Qorbani, Quistberg, Radfar, Rafay, Rafiei, Rahim, Rahimi, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahimi-Movaghar, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rahman, Rai, Rajati, Ram, Ranjan, Ranta, Rao, Rawaf, Rawaf, Reddy, Reiner, Reinig, Reitsma, Remuzzi, Renzaho, Resnikoff, Rezaei, Rezai, Ribeiro, Roberts, Robinson, Roever, Ronfani, Roshandel, Rostami, Roth, Roy, Rubagotti, Sachdev, Sadat, Saddik, Sadeghi, Saeedi Moghaddam, Safari, Safari, Safari-Faramani, Safdarian, Safi, Safiri, Sagar, Sahebkar, Sahraian, Sajadi, Salam, Salama, Salamati, Saleem, Saleem, Salimi, Salomon, Salvi, Salz, Samy, Sanabria, Sang, Santomauro, Santos, Santos, Santric Milicevic, Sao Jose, Sardana, Sarker, Sarrafzadegan, Sartorius, Sarvi, Sathian, Satpathy, Sawant, Sawhney, Saxena, Saylan, Schaeffner, Schmidt, Schneider, Schöttker, Schwebel, Schwendicke, Scott, Sekerija, Sepanlou, Serván-Mori, Seyedmousavi, Shabaninejad, Shafieesabet, Shahbazi, Shaheen, Shaikh, Shams-Beyranvand, Shamsi, Shamsizadeh, Sharafi, Sharafi, Sharif, Sharif-Alhoseini, Sharma, Sharma, She, Sheikh, Shi, Shibuya, Shigematsu, Shiri, Shirkoohi, Shishani, Shiue, Shokraneh, Shoman, Shrime, Si, Siabani, Siddiqi, Sigfusdottir, Sigurvinsdottir, Silva, Silveira, Singam, Singh, Singh, Singh, Sinha, Skiadaresi, Slepak, Sliwa, Smith, Smith, Soares Filho, Sobaih, Sobhani, Sobngwi, Soneji, Soofi, Soosaraei, Sorensen, Soriano, Soyiri, Sposato, Sreeramareddy, Srinivasan, Stanaway, Stein, Steiner, Steiner, Stokes, Stovner, Subart, Sudaryanto, Sufiyan, Sunguya, Sur, Sutradhar, Sykes, Sylte, Tabarés-Seisdedos, Tadakamadla, Tadesse, Tandon, Tassew, Tavakkoli, Taveira, Taylor, Tehrani-Banihashemi, Tekalign, Tekelemedhin, Tekle, Temesgen, Temsah, Temsah, Terkawi, Teweldemedhin, Thankappan, Thomas, Tilahun, To, Tonelli, Topor-Madry, Topouzis, Torre, Tortajada-Girbés, Touvier, Tovani-Palone, Towbin, Tran, Tran, Troeger, Truelsen, Tsilimbaris, Tsoi, Tudor Car, Tuzcu, Ukwaja, Ullah, Undurraga, Unutzer, Updike, Usman, Uthman, Vaduganathan, Vaezi, Valdez, Varughese, Vasankari, Venketasubramanian, Villafaina, Violante, Vladimirov, Vlassov, Vollset, Vosoughi, Vujcic, Wagnew, Waheed, Waller, Wang, Wang, Weiderpass, Weintraub, Weiss, Weldegebreal, Weldegwergs, Werdecker, West, Whiteford, Widecka, Wijeratne, Wilner, Wilson, Winkler, Wiyeh, Wiysonge, Wolfe, Woolf, Wu, Wu, Wyper, Xavier, Xu, Yadgir, Yadollahpour, Yahyazadeh Jabbari, Yamada, Yan, Yano, Yaseri, Yasin, Yeshaneh, Yimer, Yip, Yisma, Yonemoto, Yoon, Yotebieng, Younis, Yousefifard, Yu, Zadnik, Zaidi, Zaman, Zamani, Zare, Zeleke, Zenebe, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou, Zodpey, Zucker, Vos and Murray2018; NIH, Reference NIH2019).

The definitions of refugees (a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution, is forced to escape from his or her country) and asylum seekers (a person who seeks protection from persecution or serious harm in a country other than their own) were in agreement with the UNHCR Master Glossary of Terms (UNHCR, Reference UNHCR2006) and Asylum and Migration Glossary 6.0 (Network, Reference Network2018). No restrictions were applied to the origin of the studies. Cross-sectional studies, follow-up studies, cohort data studies and register-based studies were eligible. To reduce possible selection bias, we excluded studies conducted on samples selected in psychiatric services and concerning internally displaced people (IDPs) (UNHCR, Reference UNHCR2006).

All title and abstracts were screened by two researchers independently (MP/MS or SG). We retrieved the full texts of all abstracts that seemed eligible for inclusion. Subsequently, we performed a full-text selection according to our pre-specified eligibility criteria. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

For every eligible study, two reviewers independently (MP/MS or SG) extracted data related to the year of publication, the country of data collection, the country of the refugees' origins, the sample size of the population, the age, the gender, the time elapsed as refugees or asylum seekers, the diagnostic tool used. Finally, we extracted the prevalence rates of MDD (current episode and recurrent), PTSD, BPD and psychotic disorder. In the absence of absolute numbers and if allowed by the data reported, the percentages of prevalence rates were converted into numbers. The time since displacement was reported in three different categories: (1) people who have spent more than five years as refugees or asylum seekers (⩾5), (2) people who have spent between 5 years and 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers (>1 < 5) and (3) people who have spent less then 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers. Countries were categorised as low-, middle- (LMIC) and in high-income (HIC) based on the World Bank list of economies 2020 (WBC, Reference WBC2020).

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (MP/MS or SG) evaluated the assessment of the methodological quality of individual studies using a modified version of the Joanna Briggs tool – JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Moola, Lisy, Riitano and Tufanaru2015) based on five questions, which permitted a critical assessment of prevalence rates: (1) Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way? (2) Was the sample size adequate? (3) Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? (4) Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? (5) Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?. The response categories per each question were yes, unclear, and no. Three or more unclear or negative answers were considered to define a study with a high risk of bias (see online Supplementary materials). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by involving a third reviewer (PC).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The prevalence rates of serious mental disorders were calculated by pooling the study-specific estimates. To stabilise the variance of binomial data, the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used (Miller, Reference Miller1978). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity between studies, we computed the pooled estimates under the random effects (DerSimonian and Laird) model based on the transformed values and their variance (Nyaga et al., Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts2014). The I 2 was calculated as an indicator of the inter-study heterogeneity in percentages. Values of I 2 are considered low, moderate and high when I 2 equals 25, 50, and 75% respectively (Melsen et al., Reference Melsen, Bootsma, Rovers and Bonten2014). Based on previous meta-analyses on prevalence rates, we expected considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence estimates (Higgins, Reference Higgins2008; Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019; Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020). To examine possible sources of heterogeneity between the included studies, we ran subgroups under the mixed-effects model with inverse-variance weights under the random-effects model (time since displacement ⩾ 5 years v. time since displacement >1 < 5years v. time since displacement <1year, MINI v. other diagnostic interviews, LMICs v. HICs, high risk of bias v. low risk of bias, convenience samples v. probability-based samples). Prevalence rates were calculated per each disorder separately. Pooled rates for subgroups were indicated, when at least three studies were present for each disorder. All statistical analyses were conducted using Meta-prop package in STATA/SE 16.1 for Mac (Nyaga et al., Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts2014).

Results

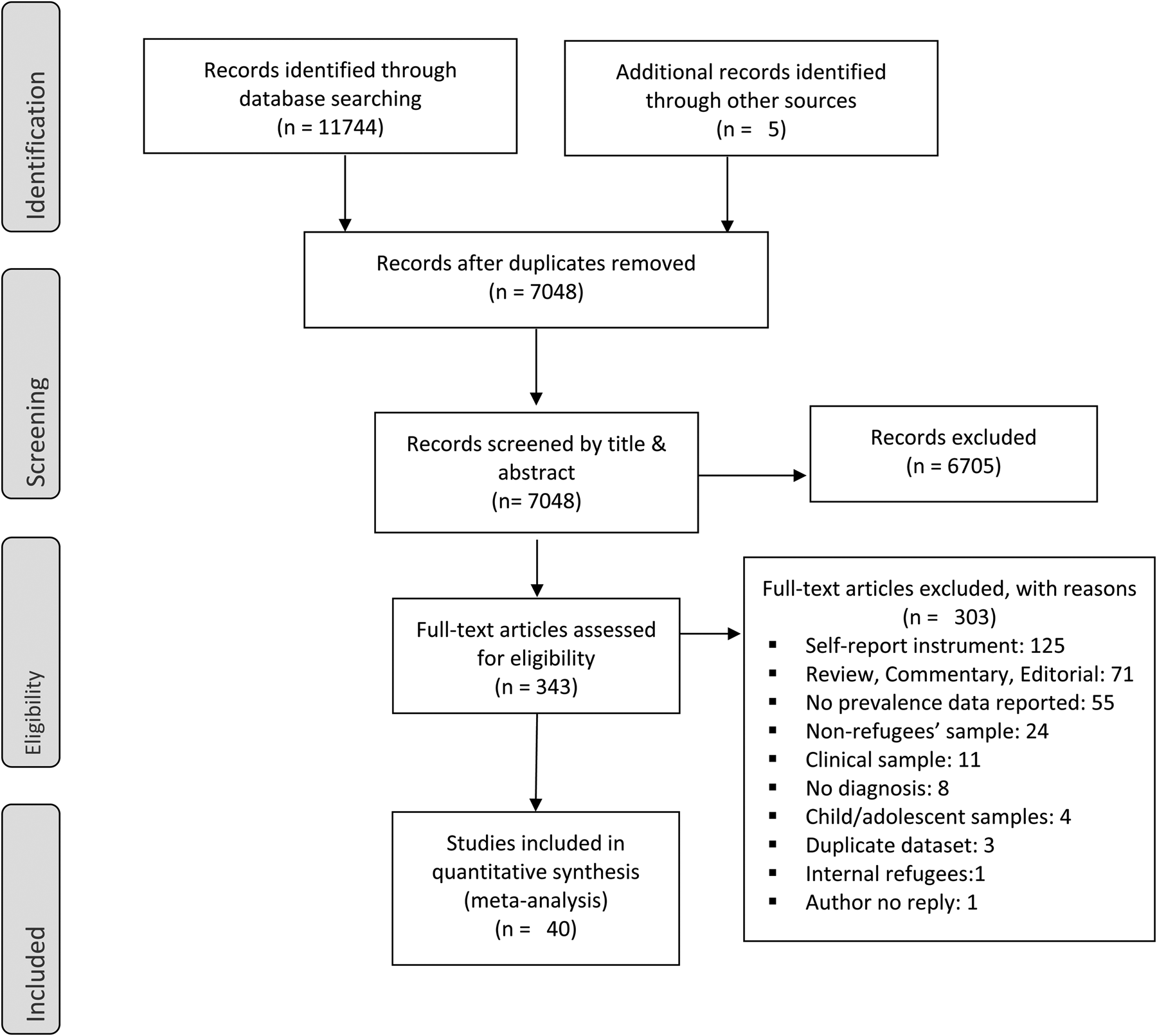

We initially identified 11 749 records. After exclusion of duplicates, 7048 records remained. We excluded 6705 studies based on titles and abstracts selection. We examined 343 full texts against our eligibility criteria and included 40 studies in the present meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Study identification, screening, and eligibility test, following the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews (PRISMA).

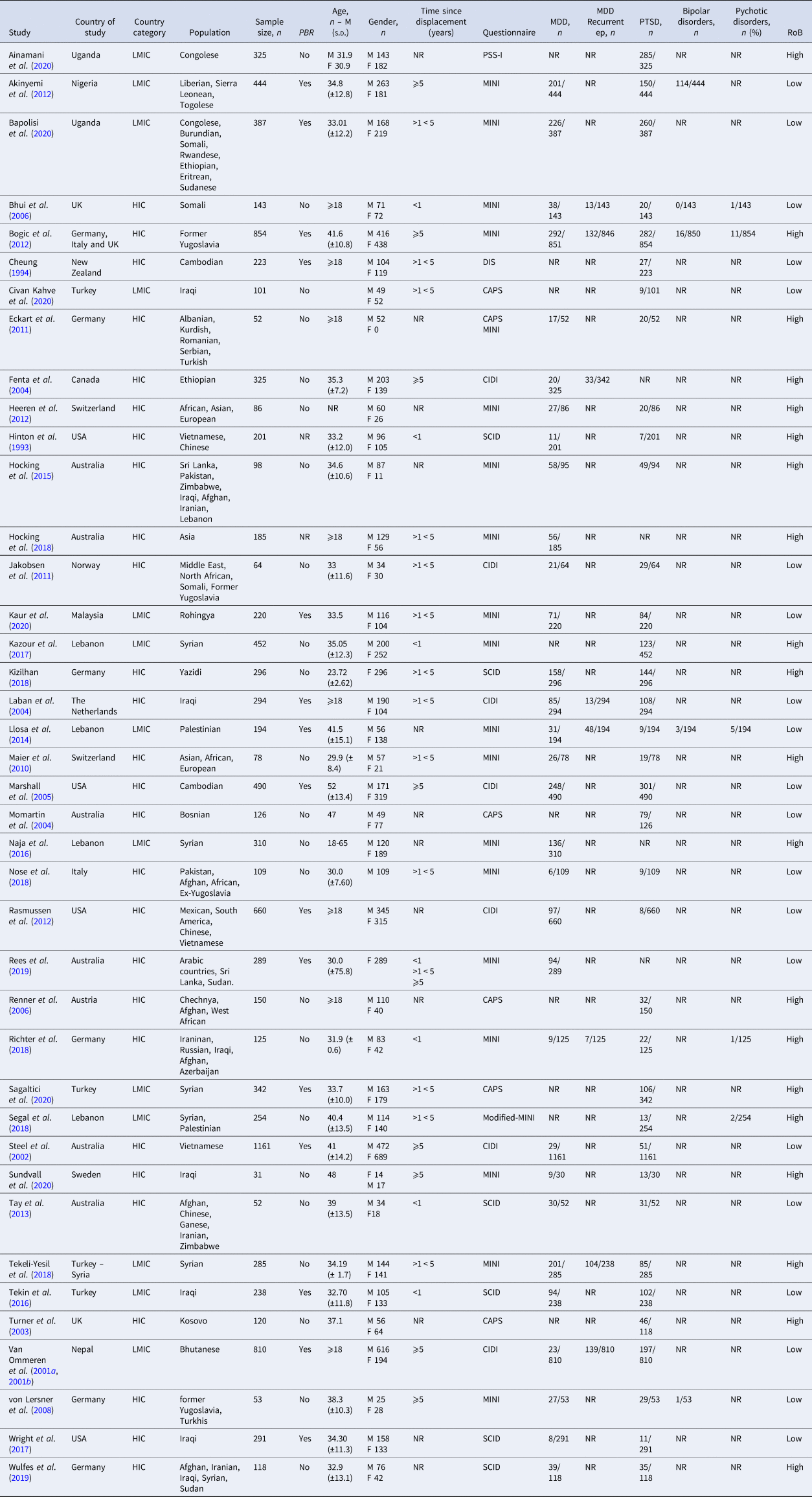

Studies included were conducted across 18 countries, 7 LMICs (Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Kazour et al., Reference Kazour, Zahreddine, Maragel, Almustafa, Soufia, Haddad and Richa2017; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Khoury, Salah and Ghannam2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Ainamani et al., Reference Ainamani, Elbert, Olema and Hecker2020; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Civan Kahve et al., Reference Civan Kahve, Aydemir, Yuksel, Kaya, Unverdi Bicakci and Goka2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sagaltici et al., Reference Sagaltici, Alpak and Altindag2020) (Lebanon, Malaysia, Nepal, Nigeria, Turkey, Syria and Uganda) and 11 HICs (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Cheung, Reference Cheung1994; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Bowie, Dunn, Shapo and Yule2003; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Renner et al., Reference Renner, Salem and Ottomeyer2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015; Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) (Australia, Austria, Canada, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, The Netherlands, United Kingdom and United States of America) and they reported the prevalence of mental disorders of 11 053 participants (5309 men – 48%). Of these 11 053 participants, 6897 (62.3%) had taken part in population-based representative surveys (PBR). The majority of the studies included have used MINI as diagnostic interview (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015, Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Kazour et al., Reference Kazour, Zahreddine, Maragel, Almustafa, Soufia, Haddad and Richa2017; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Khoury, Salah and Ghannam2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020). CIDI was used by 7 studies (Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012), SCID by six studies (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019) and one study (Cheung, Reference Cheung1994) used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule – DIS. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale – CAPS and the PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview- PSS-I were used by six studies (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Bowie, Dunn, Shapo and Yule2003; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Renner et al., Reference Renner, Salem and Ottomeyer2006; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Civan Kahve et al., Reference Civan Kahve, Aydemir, Yuksel, Kaya, Unverdi Bicakci and Goka2020; Sagaltici et al., Reference Sagaltici, Alpak and Altindag2020) and one study (Ainamani et al., Reference Ainamani, Elbert, Olema and Hecker2020) respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Studies meeting inclusion criteria

PBR, population-based representative surveys; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; HIC, High-income country; LMIC, Low middle-income country; MDD, Major depressive disorder; MINI, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NR, Not reported; PSS-I, PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview; SCID, The Structured Clinical Interview for DS.

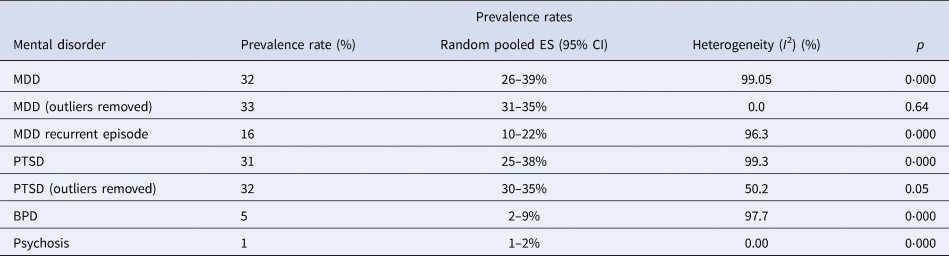

The prevalence of MDD was reported in 31 studies (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015, Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020): 23 reported only the prevalence of a current episode of MDD (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015, Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) (MDD) and 8 reported also prevalence of recurrent episode of MDD (reMDD) (Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018) (Table 1). The pooled prevalence rate of MDD was 32% (95% CI 26–39%) with a very high heterogeneity between sample (I 2 = 99.05%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of reMDD was 16% (95% CI 10–22%) and the rates ranged from 4% to 44% (I 2 = 96.3%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.2).

Table 2. Prevalence rates of serious mental disorders

MDD, Major depressive disorder; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; BPD, Bipolar disorder.

The prevalence of PTSD was reported in 36 studies (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Cheung, Reference Cheung1994; Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, Sharma, Komproe, Poudyal, Sharma, Cardena and De Jong2001b; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Bowie, Dunn, Shapo and Yule2003; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Renner et al., Reference Renner, Salem and Ottomeyer2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Kazour et al., Reference Kazour, Zahreddine, Maragel, Almustafa, Soufia, Haddad and Richa2017; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Khoury, Salah and Ghannam2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Ainamani et al., Reference Ainamani, Elbert, Olema and Hecker2020; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Civan Kahve et al., Reference Civan Kahve, Aydemir, Yuksel, Kaya, Unverdi Bicakci and Goka2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sagaltici et al., Reference Sagaltici, Alpak and Altindag2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) (Table 1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of PTSD was 31% (95% CI 25–38%) and the rates ranged from 1% to 88%. The heterogeneity between samples was high (I 2 = 99.3%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.3).

The prevalence of BPD was reported in five articles (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014) (Table 1) and the random-effects pooled prevalence was 5% (95% CI 2–9%; I 2 = 97.7%) (Table 2 and figure 2.4).

The prevalence of psychotic disorders was reported in five articles (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Khoury, Salah and Ghannam2018) (Table 1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of the psychosis was 1% (95% CI 1–2%; I2 = 0.00%) (Table 2 and figure 2.5).

To reduce the high heterogeneity and confirm our prevalence rates, we also ran analyses without the outliers when it was possible. The analysis showed a prevalence of 33% of MDD and 32% of PTSD (Table 2 and online Supplementary materials).

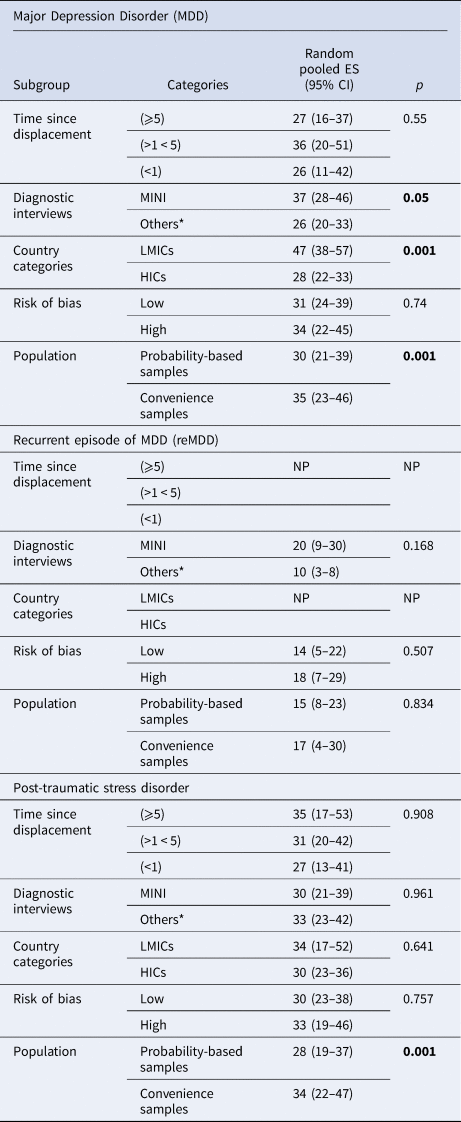

Subgroups analysis showed a significant prevalence rates difference (p = 0.001) of MDD between studies conducted in refugees resettled in LMICs (Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020) (47%; 95% CI 38–57%) and those in HICs (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015, Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) (28%; 95% CI 22–33%) (Table 3 and figure 3.1). Besides, a significant (p = 0.05) higher prevalence rate of MDD (37%; 95% CI 28–46%) has been reported in studies (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Kennedy and Sundram2015, Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) conducted using the MINI as compared to studies that used others diagnostic interviews (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Chen, Du, Tran, Lu, Miranda and Faust1993; Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019) (26%; 95% CI 20–33%) (Table 3 and figure 3.2). In addition, studies (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Bowie, Dunn, Shapo and Yule2003; Fenta et al., Reference Fenta, Hyman and Noh2004; Momartin et al., Reference Momartin, Silove, Manicavasagar and Steel2004; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Craig, Mohamud, Warfa, Stansfeld, Thornicroft, Curtis and McCrone2006; Renner et al., Reference Renner, Salem and Ottomeyer2006; Von Lersner et al., Reference Von Lersner, Wiens, Elbert and Neuner2008; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Schmidt and Mueller2010; Eckart et al., Reference Eckart, Stoppel, Kaufmann, Tempelmann, Hinrichs, Elbert, Heinze and Kolassa2011; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Thoresen and Johansen2011; Heeren et al., Reference Heeren, Mueller, Ehlert, Schnyder, Copiery and Maier2012; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Frommer, Hunter, Silove, Pearson, San Roque, Redman, Bryant, Manicavasagar and Steel2013; Naja et al., Reference Naja, Aoun, El Khoury, Abdallah and Haddad2016; Kazour et al., Reference Kazour, Zahreddine, Maragel, Almustafa, Soufia, Haddad and Richa2017; Hocking et al., Reference Hocking, Mancuso and Sundram2018; Kizilhan, Reference Kizilhan2018; Nose et al., Reference Nose, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Richter et al., Reference Richter, Peter, Lehfeld, Zaske, Brar-Reissinger and Niklewski2018; Segal et al., Reference Segal, Khoury, Salah and Ghannam2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., Reference Tekeli-Yesil, Isik, Unal, Aljomaa Almossa, Konsuk Unlu and Aker2018; Wulfes et al., Reference Wulfes, Del Pozo, Buhr-Riehm, Heinrichs and Kröger2019; Ainamani et al., Reference Ainamani, Elbert, Olema and Hecker2020; Civan Kahve et al., Reference Civan Kahve, Aydemir, Yuksel, Kaya, Unverdi Bicakci and Goka2020; Sundvall et al., Reference Sundvall, Titelman, DeMarinis, Borisova and Çetrez2020) which included participants from a convenience samples showed significant (p = 0.001) higher prevalence of MDD and PTSD (MDD: 35%; 95% CI 23–46%; PTSD: 34%; 95% CI 22–47%) than studies (Cheung, Reference Cheung1994; Van Ommeren et al., Reference Van Ommeren, de Jong, Sharma, Komproe, Thapa and Cardena2001a; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Silove, Phan and Bauman2002; Laban et al., Reference Laban, Gernaat, Komproe, Schreuders and De Jong2004; Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Schell, Elliott, Berthold and Chun2005; Akinyemi et al., Reference Akinyemi, Owoaje, Ige and Popoola2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schutzwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Crager, Baser, Chu and Gany2012; Llosa et al., Reference Llosa, Ghantous, Souza, Forgione, Bastin, Jones, Antierens, Slavuckij and Grais2014; Tekin et al., Reference Tekin, Karadag, Suleymanoglu, Tekin, Kayran, Alpak and Sar2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Talia, Aldhalimi, Broadbridge, Jamil, Lumley, Pole, Arnetz and Arnetz2017; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019; Bapolisi et al., Reference Bapolisi, Song, Kesande, Rukundo and Ashaba2020; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Sulaiman, Yoon, Hashim, Kaur, Hui, Sabki, Francis, Singh and Gill2020; Sagaltici et al., Reference Sagaltici, Alpak and Altindag2020) conducted among probability-based samples (MDD: 30%; 95% CI 21–39%; PTSD: 28% 95% CI 19–37%) (Table 3 and figure 3.3). The heterogeneity between samples was high in all the subgroup analyses (I 2 = 99.05%). The other analyses of the MDD, reMDD and PTSD subgroups, showed no significant differences among prevalence rates and high heterogeneity (Table 3 and online Supplementary materials). For psychotic disorders and BPD subgroup analyses were not conducted due to the limited number of studies.

Table 3 Subgroups analysis results

* Others: (CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; SCID, The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM); MINI, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; (⩾5): people who have spent more than five years as refugees or asylum seekers; (>1 < 5): people who have spent between 5 years and 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers; (<1): people who have spent less than 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers; HICs, High-income countries; LMICs, Low middle-income countries; NP, The aggregate prevalence of random effects was not allowed due to the limited number of the sample.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide the most recent and extensive overview of the prevalence rates of serious mental disorders across refugees and asylum-seeking populations. A comprehensive search was performed from inception to June 4, 2020 and was not intentionally updated to avoid interference caused by the effect of COVID-19 pandemic in this population. We included 40 studies in 11 053 participants, and all diagnoses were established with diagnostic interviews. Our study revealed that the most prevalent serious mental disorder in refugees and asylum seekers was MDD (32%), followed by PTSD (31%), recurrent episode of MDD (16%), and BPD (5%). The prevalence of psychotic disorders was 1%. Subgroup analyses showed that MDD appeared to be more prevalent (47%) among studies conducted in LMICs than in HICs (28%), and when the MINI (37%) has been used, compared to other diagnostic instruments (26%). PTSD and MDD showed higher prevalence rates (34% and 35% respectively) in studies where participants were from convenience samples in comparison to studies that used probability-based samples. PTSD and MDD were the most frequently evaluated disorders with 36 studies and 32 studies respectively, as opposed to BPD and psychosis of which we had only a few studies.

According to previous studies, the world-wide prevalence rate reported for MDD is 4.4% (WHO, Reference WHO2017), the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in World Mental Health Surveys has been calculated between 3.9% and 5.6% (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Ratanatharathorn, Ng, McLaughlin, Bromet, Stein, Karam, Meron Ruscio, Benjet, Scott, Atwoli, Petukhova, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bunting, Ciutan, de Girolamo, Degenhardt, Gureje, Haro, Huang, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Sampson, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Williams, Xavier and Kessler2017) and the prevalence rates of psychosis and BPD in the general population are 0.4% (Moreno-Kustner et al., Reference Moreno-Kustner, Martin and Pastor2018) and 2.5%, respectively (Carta and Angst, Reference Carta and Angst2016). Comparing our results with the prevalence of the same disorders in the general population, suggests that MDD is seven times more likely in refugees and PTSD is 4 to 5 times more prevalent than in the general population (Koenen et al., Reference Koenen, Ratanatharathorn, Ng, McLaughlin, Bromet, Stein, Karam, Meron Ruscio, Benjet, Scott, Atwoli, Petukhova, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Bunting, Ciutan, de Girolamo, Degenhardt, Gureje, Haro, Huang, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Sampson, Ten Have, Torres, Viana, Williams, Xavier and Kessler2017; WHO, Reference WHO2017). Although BPD and psychosis are much rarer than MDD or PTSD, our study also indicated that externally displaced refugees and asylum seekers are two times more likely to be diagnosed with BPD and with psychosis than the general population (Carta and Angst, Reference Carta and Angst2016; Moreno-Kustner et al., Reference Moreno-Kustner, Martin and Pastor2018). Studies have highlighted the role of trauma and stress experienced by minorities, social defeat, and discrimination as important risk factors for psychosis in refugees (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Henssler, Müller, Wall, Gabel and Heinz2019; Duggal et al., Reference Duggal, Kirkbride, Dalman and Hollander2020; Selten et al., Reference Selten, van der Ven and Termorshuizen2020).

Our results are in line with the prevalence rates of the Blackmore and colleagues (Blackmore et al., Reference Blackmore, Boyle, Fazel, Ranasinha, Gray, Fitzgerald, Misso and Gibson-Helm2020) study, who found a prevalence rates of 31.4% (95% CI 24.43–38.5) for PTSD, of 31.5% (95% CI 22.64–40.38) for depression, and 1.5% (95% CI 0.63–2.40) for psychosis. In addition, our study reports the random-effects pooled prevalence for BPD which has never examined before. Compared to the 2005 systematic review findings (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005), our rates prevalence showed an increase of serious mental disorders prevalence among refugees and asylum seekers from 5% (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005) to 32% for MDD, and from 9% (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005) to 31% for PTSD. One of the reasons for the discrepancy between these results could be the LMICs exclusion in Fazel and colleagues' systematic review. Furthermore, it might be explained by increased exposure to adverse events, increased financial hardship, social isolation, decreased access to adequate health care, as well as the lack of appropriate policies and investments in the last 15 years.

Our study methodology has several strengths, among which strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, a large number of included studies, and updated statistical methods. However, due to the low number of studies that examine refugees and asylum seekers separately, a limitation of this study was to consider these two groups together. Further, we found a large variability of prevalence rates and a high level of heterogeneity between studies. While high heterogeneity is very common in meta-analyses on prevalence rates (Higgins, Reference Higgins2008), we examined possible sources of heterogeneity between the included studies. Running the analyses without outliers did not alter the main results. Upon inspection of the pattern of outliers, no systematic differences between outlier studies from the rest of the studies were identified that might explain the high heterogeneity. However, due to the limit number of studies greater caution is required in interpreting the prevalence rates of BP and psychosis. In addition, we analysed subgroups under the mixed-effects model with inverse-variance weights under the random-effects model. The results of these subgroup analyses showed that significantly higher prevalence rates of MDD and PTSD in studies conducted among convenience samples than in studies that used probability-based samples. This result highlights the importance of having an adequate statistically representative sample of participants to avoid overestimating prevalence rates in a population as various and difficult to study as that of refugees and asylum seekers.

Furthermore, higher prevalence rates of MDD were found in LMICs than in HICs. This difference was not found for PTSD, where the prevalence rate was comparable between refugees and asylum seekers resettled in LMICs and HICs. The higher prevalence of MDD in refugees resettled in LMICs may be driven by higher exposure to post-migration living difficulties. Feelings of hopelessness, the failure of the migration project, and difficulties in integration may promote higher levels of depression (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009; Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). Further, refugees resettled in LMICs can have a higher risk of developing MDD because of the lack of integration programs and mental health care due to the low investments in mental health care that unfortunately characterises the majority of these countries (Patel, Reference Patel2007). On the other hand, compared to MDD, PTSD may have a stronger association with trauma exposure in the country of origin, which may not differ significantly between refugees in LMICs and HICs.

Another interesting finding was that we found a higher rate for MDD for studies conducted with the MINI than in studies that used different diagnostic interviews. This may be explained by the fact that the MINI may be administered by non-clinicians (similar to the CIDI, but dissimilar to the SCID I/P), and that its administration is shorter and its outcomes therefore potentially less precise.

Despite the high heterogeneity and methodological limitations of included studies, a high prevalence of serious mental disorders was found in refugees and asylum seekers diagnosed through structured clinical interviews. However, specific instruments culturally adapted for use across different local cultures and contexts for refugees would be advisable, since no one of the diagnostic instruments currently in use has been developed for the non-western populations, who represent the highest sample of refugees. For this reason, to reduce the high heterogeneity, more rigorous studies, using representative samples and culturally adapted instruments, to measure cultural concepts of distress would be recommended. Moreover, to strengthen the evidence base concerning the more serious mental disorders, further research on the prevalence of psychosis and BPD is imperative. To follow this goal, international and government investments in mental health research, population screening, and specific interventions on asylum seekers and refugees are warranted. However, until we have more rigorous studies and adequate diagnostic tools, due to the high heterogeneity between these studies, our results should be considered with caution.

Conclusion

In sum, our systematic review and meta-analysis show that it is imperative that governments and actors across the world acknowledge the devastating effect of war and prosecution on individuals' mental health. In order to prevent cycles of violence and victimisation, effective public mental health responses may be put in place to address worldwide suffering.

Data

All the data involved have been included in Tables and Figures of this paper, including online Supplementary materials.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.29.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This work was supported by Ayala Scholarship of Sapienza Foundation of Rome in Italy. Ayala Scholarship of Sapienza Foundation of Rome did not participate in any part of the process of the study (study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing the paper). The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.