Impact statement

The impact of this scoping review, a type of analysis that looks at all the research on a specific topic, shows much of our data on adults with preexisting serious mental health conditions (SMHCs) who are then exposed to trauma in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) come from a small subset of countries and certain types of interpersonal violence.

History of the topic: Trauma exposure and SMHCs, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have been shown to be interconnected. Most of the research in this area has focused on childhood trauma as a risk factor for developing an SMHC, and the bulk of this work has come from studies in high-income countries in North America and Western Europe. While it is often stated that people with SMHCs are more vulnerable to experiencing traumatic events than the general public, there is less research on having an SMHC as a risk factor for exposure to traumatic events, and particularly on populations in LMICs, which have been underrepresented in research to date. This scoping review aims to fill this gap and to synthesize what trauma types adults with SMHCs face in LMICs.

Main takeaways: After a thorough search, we found that studies on this topic came from only 10 countries (out of more than 130 LMICs) and two-thirds of these were from India, Ethiopia and China. The vast majority of these studies were about interpersonal violence, such as sexual violence, intimate partner violence and physical violence, and more than one-fifth of these were on physical restraint, such as chaining. There were no studies on man-made or natural disasters. The findings support that adulthood trauma exposure among people with SMHCs is an existing issue in LMICs and is a call to action to eradicate violent practices in both community and healthcare settings.

Introduction

There is an established link between trauma exposure and serious mental health conditions (SMHCs), such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder (Grubaugh et al., Reference Grubaugh, Zinzow, Paul, Egede and Frueh2011; Mauritz et al., Reference Mauritz, Goossens, Draijer and van Achterberg2013). Many studies have shown that trauma exposure, often defined as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), poses a significant risk for the development of SMHCs (Read et al., Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012; Woolway et al., Reference Woolway, Smart, Lynham, Lloyd, Owen, Jones, Walters and Legge2022). Most of the research on trauma and SMHCs has focused on childhood adversity and in samples from high-income countries in Europe, North America and Australasia (Read et al., Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012; Woolway et al., Reference Woolway, Smart, Lynham, Lloyd, Owen, Jones, Walters and Legge2022).

Multiple models have been proposed to explain why exposure to trauma, and particularly childhood adversity, may increase the risk for developing an SMHC, including the stress-vulnerability model (Zubin and Spring, Reference Zubin and Spring1977). This model posits that some people have a biological vulnerability to SMHCs. While individuals may be able to withstand a certain amount of stress, once a certain threshold of stress is reached or a stressor is particularly intense, people become more susceptible to developing SMHCs.

Likewise, researchers have also argued that people with SMHCs may be more vulnerable to exposure to trauma than those without such conditions. Population studies have found people with SMHCs report more victimization than the general public (Maniglio, Reference Maniglio2009; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, van Busschbach, van der Stouwe, Aleman, van Dijk, Lysaker, Arends, Nijman and Pijnenborg2019). One theory for this is that people with SMHCs may have cognitive impairments that impact their decision-making and problem-solving abilities, restricting their ability to navigate potentially dangerous situations (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, van Busschbach, van der Stouwe, Aleman, van Dijk, Lysaker, Arends, Nijman and Pijnenborg2019). People with SMHCs may also be exposed to trauma through settings due to their mental health conditions, such as inpatient and outpatient healthcare centers. Patients with SMHCs have reported high rates of trauma exposure in psychiatric settings, including physical and sexual assault by staff, police and other patients (Frueh et al., Reference Frueh, Knapp, Cusack, Grubaugh, Sauvageot, Cousins, Yim, Robins, Monnier and Hiers2005; Lundberg et al., Reference Lundberg, Johansson, Okello, Allebeck and Thorson2012a).

Like the childhood adversity literature, the research on having an SMHC as a risk factor for trauma exposure in adulthood has also primarily been from samples in high-income countries (Maniglio, Reference Maniglio2009; de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, van Busschbach, van der Stouwe, Aleman, van Dijk, Lysaker, Arends, Nijman and Pijnenborg2019). Deepening research in LMICs may shed light on the possibility of unique traumas in this population. Furthermore, identifying and codifying trauma exposure in this population may raise awareness about such incidents and lead to healthcare and human rights policy changes for people with SMHCs (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Liu, Wu, Chen, Wang, Ma, Wang, Good, Ma, Yu and Good2015; Hidayat et al., Reference Hidayat, Oster, Muir-Cochrane and Lawn2023).

This scoping review aims to fill this gap by synthesizing the literature on trauma that adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or depression with psychotic features are exposed to in LMICs, which have been less represented in research to date.

We framed this exploratory study around Peters et al.’s population, concept, context framework for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Marnie, Tricco, Pollock, Munn, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey and Khalil2021). Our primary research question aimed to establish the evidence base on adult trauma exposure experienced by people with SMHCs in LMICs. In other words, what is the extent, range, and nature of research about adults with SMHCs (population) being exposed to a traumatic event in adulthood (concept) in an LMIC (context)?

Our secondary research question was to ascertain whether there were any trends in the data; for example, whether there were trauma types or demographics that were more commonly studied than others. We expected most trauma exposures would be types of interpersonal violence (use of physical, sexual or psychological force against another person or small group of people) (Mercy et al., Reference Mercy, Hillis, Butchart, Bellis, Ward, Fang and Rosenberg2017) and human rights violations, such as solitary confinement for multiple years.

Methods

We followed the JBI updated guidelines for the conduct of scoping reviews (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Marnie, Tricco, Pollock, Munn, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey and Khalil2021). As part of the review, we developed an extensive search query, retrieved all articles, conducted multiple phases of screening, extracted the data and synthesized the results. We outline each step below.

Search strategy: We developed our search strategy to run in five databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad. We started with PubMed and used a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH), some of which were “exploded” to retrieve any citations that fell under its subheadings, title and abstract (tiab) fields, and keyword (kw) fields. We used Boolean operators to develop a search query based on more than 300 terms and phrases connected to SMHCs, traumatic events and LMICs.

For SMHCs, we included words that were often associated with this term, such as “schizophrenia,” “serious mental illness” and “psychotic disorder.”

For trauma exposure, we pulled terms from two commonly used measures that assess potentially traumatic events: the Life Events Checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition (LEC-5) (Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Blake, Schnurr, Kaloupek, Marx and Keane2013) and the posttraumatic stress disorder module of the World Mental Health Survey version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler and Üstün, Reference Kessler and Üstün2004), which is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). We then expanded the terms from the LEC-5 and the CIDI to include specific examples of the type of trauma in question. For example, for “natural disasters,” we listed this term and also listed typhoons, landslides, tsunamis, etc. A priori, on the basis of qualitative studies with people with SMHCs in LMICs and commentaries by leaders in the field (Alem, Reference Alem2000; Ametaj et al., Reference Ametaj, Hook, Cheng, Serba, Koenen, Fekadu and Ng2021), we included events that may be more common in LMICs than in high-income countries, although they can happen anywhere, including human rights violations, mob justice, chaining and restraining. Additionally, we included the term “idiom(s) of distress” to potentially retrieve articles that might have focused on expressions of trauma not typically captured in “Western” terminology.

For LMICs, we included the name of every country that was classified as an LMIC by the World Bank as of November 2023 (World Bank, 2023) (i.e., Afghanistan) as well as unrecognized countries or disputed territories that were not on the World Bank list but still met criteria as an LMIC (i.e., Somaliland). We also added overarching categories that are sometimes used to describe these groupings, such as “South Asia,” “developing country,” and “Global South.”

We then adapted the search string to Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad using their controlled subject vocabulary. See Supplemental File 1 for the full search strings for each database.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Our inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion:

-

• Adults aged ≥18 years.

-

• People with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or depression with psychotic features.

-

• Trauma exposure must have occurred after the psychiatric diagnosis.

-

• Study population was in an LMIC.

-

• Observational studies only.

-

• Empirical studies in peer-reviewed journals, including case studies, qualitative studies and quantitative studies.

-

• There were no restrictions on the language in which the article was written.

-

• There were no restrictions on the date the article was published.

Exclusion:

-

• Studies with data collected in high-income countries.

-

• Studies where it was not clear when the trauma occurred and the diagnosis of the mental health condition occurred.

-

• Studies where the trauma only occurred in childhood, adolescence or youth.

-

• Children (people aged <18 years).

-

• Intervention studies (i.e., randomized control trials).

-

• Conference papers and abstracts, commentaries, letters, news articles, scoping reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and gray literature.

-

• Biological process studies such as biomarkers, genetic studies, biospecimens and circuitry.

-

• Animal studies.

There were a few caveats to these criteria. If we could not distinguish whether an article included participants with depression vs. depression with psychotic features, we kept the article in. If an article was about “psychiatric conditions,” but we could not split out data from the disorders that met our eligibility criteria (i.e., schizophrenia) from the overall grouping, we excluded the article. If an article included participants under 17.9 years and we could separate out data for participants ≥18, we included the article and only reported on data pertaining to adults. If we could not split out participants under 17.9 from ≥18 (for example, if the age range was 15–49), the article met all our other eligibility criteria and the mean age of participants was ≥18, we included the article.

Reviewing retrieved articles

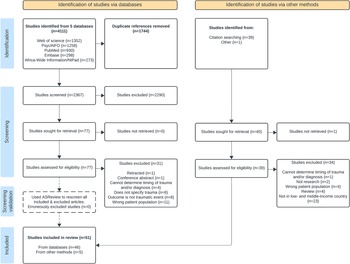

We ran our search on December 20, 2023, downloaded the citations from the retrieved articles and imported them into Covidence (www.covidence.org [Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, 2024]). Following the removal of duplicate articles in Covidence, we followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks and Hempel2018) process and created a flowchart to capture each stage (see Figure 1).

We screened the remaining articles in two stages. First, two reviewers (AS and EG) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The same reviewers then independently screened the full text of the remaining articles to assess eligibility. At both stages, for articles that were in conflict, the two reviewers discussed the articles and came to a consensus on whether they met eligibility. Following confirmation that an article met the criteria, we hand-searched its reference list to identify additional articles that should be reviewed (Dundar and Fleeman, Reference Dundar, Fleeman, Boland, Dickson and Cherry2017).

We then moved all articles into the data extraction pool. We created a Google Sheet to extract a range of fields from each article: article information (i.e., first author and title), study design, sample size, sex/gender of participants (% female), mean age, racial/ethnic composition, participant psychiatric diagnosis, method of assessment for the psychiatric condition, type of trauma exposure, tool used to assess trauma exposure, and country and municipality where the participants were recruited. AS extracted data for each article, and another reviewer independently extracted data from the same article. They then cross-checked each other’s work to ensure accuracy. We held group discussions when there were divergent decisions and came to a consensus on the final answer.

Search procedure validation

In order to validate our search procedure and to confirm that we did not exclude any articles in the screening stages that should have been included, we used a machine learning tool, ASReview version 1.6.2 (https://asreview.nl/ [van de Schoot et al., Reference van de Schoot, de Bruin, Schram, Zahedi, de Boer, Weijdema, Kramer, Huijts, Hoogerwerf, Ferdinands, Harkema, Willemsen, Ma, Fang, Hindriks, Tummers and Oberski2021]) to additionally re-check the excluded articles. ASReview is an open-source software that utilizes active-learning to screen large amounts of data primarily for scoping and systematic reviews. For this process, we uploaded all the articles from the original screening phase (following the removal of the duplicates). We then selected one article that met inclusion criteria and one that did not train the software on which articles should be included/excluded. We screened 407 articles in total, labeling each one as “relevant” (likely met inclusion criteria) and “irrelevant” (did not meet inclusion criteria). From the articles we labeled as relevant, we cross-checked these against our final list of included articles and reread the full text of any articles we had originally excluded to determine whether they met inclusion criteria.

Synthesis plan

The synthesis plan was a narrative summary following guidelines from (Cumpston et al., 2022) in which we focused primarily on the types of studies included, countries where the data collection took place and types of trauma reported. We presented the charting results as text in a table and graphical summaries of the research data.

We did not conduct a formal publication bias analysis as this is not typically done in scoping reviews (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Marnie, Tricco, Pollock, Munn, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey and Khalil2021).

Protocol deposit

The protocol for this study is available through Open Science Framework and can be found here: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/JRSQP.

Results

We ran our search in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection and Africa-Wide Information/NiPad, which retrieved 4,111 articles. After uploading all search results into Covidence, we removed 1,744 duplicates and were left with 2,367 articles for title and abstract screening. AS and EG double screened all titles and abstracts and removed 2,290 irrelevant studies. Their agreement rate was 97.5%. We then reviewed the full text of 77 articles. Forty-six studies met the criteria for inclusion. For the hand-searching process, AS identified 39 citations for articles to screen; after going through the full screening process for these articles, AS found four that met eligibility. In addition, AS discovered an additional article that met the criteria during a separate literature review. AS added these five articles to the pool for extraction. Using ASReview, AS tagged 57 articles as relevant, of which 46 were already in our included pool. Upon rereading the additional 11, they still did not meet our inclusion criteria; thus, the software did not identify any erroneously excluded articles.

We were left with 51 articles that met the criteria. (See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram that captures the search and selection process.)

We then extracted data from all the remaining articles into a Google document (see Table 1 for the articles that met eligibility and the data we extracted from each). There was 1 case study, 1 mixed-methods study (both qualitative and quantitative measures), 12 qualitative studies and 37 quantitative studies. Of the quantitative studies, the majority were cross-sectional. There were nine studies reporting on mortality, all of which were cohort studies, some of which followed patients for years and some which used national or regional health records to determine mortality rates. The number of participants in the studies ranged from 1 to 72,021,918. The percentage of female participants ranged from 0% to 100%. For studies that provided a mean age of participants (n = 42), the average age ranged from 26.7 to 51.9 years. The most represented countries were India (n = 19), Ethiopia (n = 9) and China (n = 6), which made up two-thirds of the studies. Additional countries represented in the studies were Indonesia (n = 5), Nigeria (n = 3), Uganda (n = 3), Brazil (n = 2), Egypt (n = 2), Ghana (n = 1) and South Africa (n = 1). The most studied mental health condition was schizophrenia. The most studied traumatic event was interpersonal violence (76.5%–84.3%)Footnote 1 including intimate partner violence and sexual and physical victimization types. Of the types of interpersonal violence, more than one-fifth were about physical restraint, which ranged from shackling people by their ankles to a tree to chemical restraint in a hospital (23.3%–34.9%)Footnote 1. There were no studies on man-made or natural disasters.

Table 1. Articles and their characteristics included in the scoping review

Acronyms: BP = bipolar disorder; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; IPV = intimate partner violence; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; N/A = not applicable; OPCRIT = Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness; PSE = Present State Examination; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCZ = schizophrenia; SMI = severe mental illness or serious mental illness; SZA = schizoaffective disorder; WHO = World Health Organization.

Note: the terminology in the table reflects the language the researchers used in their articles, such as SMI.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart of the search and selection process for the scoping review.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to synthesize the existing literature on trauma exposure experienced by adults with preexisting SMHCs in LMICs. By including multiple types of studies, we captured a breadth of trauma types and SMHCs that inform the different ways we conceptualize trauma exposure across mental health diagnoses in LMIC settings. The range of sample sizes, sexes represented, age of participants and variation in diagnoses also illustrates the diversity of studies in the field, which may make the findings more reflective of real-world experiences of patients with SMHCs.

Of the 51 included articles, India, Ethiopia and China made up more than 66% of the studies; thus, even though there was a broad range of types of studies and demographics, our understanding of the field derives from a small subset of countries. For example, eight of the nine mortality studies were from India, Ethiopia and China, providing data on traumas that led to death in these populations. Furthermore, with only 10 countries represented in total, there were no data from the more than 120 other LMICs. Though the additional articles outside of India, Ethiopia and China included studies from Southeast Asia, South America and Africa, these regions and the countries within them have diverse populations, geographies and cultures. As such, the studies included may not reflect the full scope of types and frequencies of traumas that people with SMHCs face within and across such heterogeneous LMICs.

Interpersonal violence, which accounted for the majority of studies, emerged as a significant category of traumatic events. Such studies support the notion that people with SMHCs are at additional risk for victimization given their mental health conditions. For example, having an SMHC is associated with social and physical isolation and potential cognitive impairments and/or symptoms (i.e., positive and negative symptoms), which increase the likelihood of being targeted by a perpetrator (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, van Busschbach, van der Stouwe, Aleman, van Dijk, Lysaker, Arends, Nijman and Pijnenborg2019). Alternatively, in many studies family members said they had tied up their loved ones in order to protect them from harm in the community and had no other options given the lack of treatment options and accessible and affordable health care (Asher et al., Reference Asher, Fekadu, Teferra, De Silva, Pathare and Hanlon2017).

One type of interpersonal violence, “chaining” and “restraining,” represented a significant percentage of events. However, the type of restraint differed widely. While some participants were kept in wooden cages in their community for years, some were in solitary isolation as inpatients for a short period. In both high-income countries (the United States) and in LMICs (Ethiopia and China), people with SMHCs have described restraint as traumatizing (Frueh et al., Reference Frueh, Knapp, Cusack, Grubaugh, Sauvageot, Cousins, Yim, Robins, Monnier and Hiers2005; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Xiang, Zhou, Gou, Himelhoch, Ungvari, Chiu, Lai and Wang2014; Ametaj et al., Reference Ametaj, Hook, Cheng, Serba, Koenen, Fekadu and Ng2021). In Uganda, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has described the use of physical, mechanical and chemical restraints and isolation/seclusion in psychiatric facilities in conflict with the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ Article 15 (“Freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” for all people) (OHCHR, 2016).

Even in nonpsychiatric contexts, there is evidence that physical restraint can lead to physical and psychological harm, including PTSD (Franks et al., Reference Franks, Alcock, Lam, Haines, Arora and Ramanan2021). The concept of restraint can be controversial, however, because it can be deemed necessary by hospital staff for a patient’s safety depending on an institution’s clinical guidelines. Restraint is also not captured by measures that are often used to assess trauma exposure such as the LEC and the CIDI. Such standardized measures can sometimes fail to capture a wider range of exposures as well as the subjective nature of what is considered traumatic. This may have affected how participants reported traumatic events in these countries.

This is particularly relevant in non-Western settings. Some researchers maintain that the acknowledgment of traumatic events and subsequent traumatic stress is not simply a response to objective experiences, but is shaped by the culture in which one exists and is understood through what is considered traumatic in their setting (Chentsova-Dutton and Maercker, Reference Chentsova-Dutton and Maercker2019). The value of including qualitative research is that it can augment quantitative reports by offering insights into personal trauma experiences and contextual factors in these settings.

Surprisingly, there were no studies about man-made or natural disasters, such as war, fires and landslides. There is literature about vulnerable populations being left behind in dangerous situations because they are incapable of fleeing, such as the elderly in conflict zones (Murthy and Lakshminarayana, Reference Murthy and Lakshminarayana2006) or during environmental crises like Hurricane Katrina (Dosa et al., Reference Dosa, Feng, Hyer, Brown, Thomas and Mor2010). However, none of these trauma types were elicited in this search. It is possible that this is because it is harder to conduct research during events like wars (Cohen and Arieli, Reference Cohen and Arieli2011), and this absence partially reflects a survival bias. That is, people with SMHCs who died during disasters may not be represented in studies. Despite this, there were mortality studies in the scoping review that captured types of traumas that led to death, somewhat counterbalancing this potential survival bias. Such studies were conducted in more controlled environments in which populations could be followed for years or in countries where there were strong national or regional electronic medical records where accurate patient outcome data could be pulled more easily.

Limitations

There are some limitations that should be noted here. Although we tried to capture an extensive range of trauma types, we know that there are traumas that are culturally relevant in the countries we looked at that might not meet DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria. While we tried to account for this by including “idioms of distress” and terminology about human rights violations and chaining/restraint, it is likely that there were trauma types that have not been studied by researchers in these contexts or that used different terms from ours that we did not retrieve. In addition, if an article did not include the name of the country in its title or abstract or a grouping term for the countries that met our criteria (i.e., “LMIC” or “East Africa”), we would likely have missed it. We may have missed articles that were not indexed in the American or European databases used here, as some articles from LMICs do not get included in these databases. However, we included Africa-Wide Information/NiPad in order to capture some of the articles that might have been otherwise missed. We limited inclusion to published studies in the interest of completing this scoping review in a timely manner. We acknowledge that excluding gray literature may potentially introduce publication bias. Inclusion of gray literature to address this research question should be considered in a future systematic review. Lastly, we did not include articles with potential mediators between SMHCs and trauma exposure, such as substance use or economic disadvantage. Studies with mediators would be worthwhile to look at in the future.

Conclusion

Future research on trauma types that people with SMHCs are exposed to in LMICs should expand beyond 10 countries to more than 120 additional countries that qualify as LMICs. Research on man-made and natural disasters in this population is warranted. Additional qualitative research may help identify locally relevant trauma types as well as understand people’s lived experiences.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.123.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found as a Word document, which is attached to this article.

Data availability

No new data were created as part of this manuscript. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Supriya Misra, Carol Mita, Carrie G. Wade, Lucia Fernandez, Almalina Gomes and Sofia Paredes.

Author contribution

Study conceptualization: AS; Search query development: AS with input from Carol Mita and Carrie G. Wade at Countway Library; First draft of the manuscript: AS; Revising it critically for important intellectual content: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS; Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work: AS, EG, BK, BH and SS; Final approval of the version to be published: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: AS, EG, BK, BH, KCK and SS.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

None.

Comments

Dear Drs. Bass and Chibanda,

We are pleased to submit an original research article, “Serious mental health conditions and exposure to adulthood trauma in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review,” for consideration by Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

This review aims to synthesize the nature and extent of research on traumatic events that adults with serious mental health conditions (SMHCs), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, face in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and offers an important contribution to the field of trauma and mental health conditions.

There is a strong link between trauma exposure and SMHCs. The majority of research in the field has focused on childhood trauma as a risk factor for developing a SMHC and on samples from high-income countries. There is less research, however, on having a SMHC as a risk factor for exposure to traumatic events, and particularly on populations in LMICs.

After conducting a search across <b>5 databases, 51 articles met criteria for inclusion of which 66% were from India, Ethiopia, and China. More than 76% of the trauma exposures were on interpersonal violence, such as sexual and physical violence. Of the interpersonal violence studies, more than 23% were on physical restraint (e.g., shackling).</b>

<b>Main takeaways:</b> Much of our data in this population is informed by a small subset of countries and by certain types of interpersonal violence. Future research should aim to expand to additional countries in LMICs. Additional qualitative research would likely identify context-relevant types of traumas amongst this population.

As we know it <b>can be challenging to find reviewers for manuscripts, we have suggested 15 potential reviewers</b> who have extensive experience in the intersection of trauma exposure and psychosis, and many of them are from the countries which are cited in the manuscript.

As the corresponding author, I take full responsibility for the content and integrity of the manuscript, and I confirm that it is not under review at any other journal.

Kind regards,

Anne Stevenson

Stellenbosch University

<u>Potential reviewers:</u> (full names, emails, and affiliations are in the portal)

1 Taiwo Opekitan Afe afeet23@yahoo.co.uk;

2 Laura Asher Laura.Asher@nottingham.ac.uk;

3 Ursula M Read ursula.read@warwick.ac.uk;

4 Vuyokazi Ntlantsana Ntlantsanav@ukzn.ac.za;

5 Keneilwe Molebatsi Molebatsik@ub.ac.bw;

6 Habte Belete habte.belete@gmail.com;

7 Richard Stephen Mpango Richard.Mpango@lshtm.ac.uk;

8 K Janaki Raman janakitrichy@gmail.com;

9 Lynette Moodley lynette_moodley@yahoo.ca;

10 Bonga Chiliza ChilizaB@ukzn.ac.za;

11 Iyus Yosep iyuskasep_07@yahoo.com;

12 Atalay Alem atalay.alem@gmail.com;

13 Heni Dwi Windarwati henipsik.fk@ub.ac.id;

14 Anindita Bhattacharya ab4050@uw.edu;

15 Guru S. Gowda drgsgowda@gmail.com.