1. Introduction

In recent decades, many welfare states have reduced the state's responsibility for providing public services (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001; Abramovitz, Reference Abramovitz, Gray, Midgley and Webb2012), parallel to the development of the New Public Management (Pollitt and Bouckaert, Reference Pollitt and Bouckaert2004) and post-New Public Management (Christensen and Lægreid, Reference Christensen and Lægreid2011) waves of reform. Often, these processes have not been carefully planned at the national level, making ad-hoc cuts and retrenching services without clearly specifying who is responsible for the neglected public services that result (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001; Hacker, Reference Hacker2004; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck, Thelen, Streeck and Thelen2005).

The retreat of the state from providing services often pushes citizens to take care of themselves and look for alternative methods of obtaining the services they had previously received from the government. This may be an easy task if there is a private market that offers services at affordable prices, leading to a process termed privatization by displacement (Savas, Reference Savas2000). However, when such a market does not exist, either because it did not evolve under the monopolistic status quo or because the private goods and services are very expensive, many citizens look for alternative methods that are neither entirely public nor private (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012). These alternatives mix public and private resources and channels, and often are either illegal or on the margins of the law. Shadow economies and black market medicine are good exemplars of such solutions (Savas, Reference Savas2000: 137; Helmke and Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004; Schneider, Reference Schneider2007). Other examples include making extra, informal payments to health care suppliers in order to receive better treatment. Furthermore, free market advocates often claim that by turning to such alternative methods people indicate their preference for private services and use these claimed signals to justify privatization (Savas, Reference Savas2000). It is therefore essential to understand how people formulate their preferences about such alternative modes of obtaining services and whether these preferences express prior deeply held beliefs or are a response to the changing reality.

Hence, the context of the paper is a situation in which highly centralized health care services are the norm, and legally operating private markets in this area barely exist. As a whole, this situation characterizes what has been called the Mediterranean welfare state. Following Esping-Andersen's (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) influential book on welfare capitalism, scholars identified several models of welfare regimes, one of which they called the southern model of the Mediterranean welfare state (Leibfried, Reference Leibfried, Ferge and Kolberg1992; Castles, Reference Castles1995; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996). As we will explain in greater detail, such regimes foster the emergence of shadow economies that people use to obtain the services they want but cannot get otherwise.

We develop a rationale for explaining citizens' behavior in such circumstances. We investigate the extent to which it is motivated by intrinsic factors, such as normative views about the responsibility of the government, or by extrinsic factors, such as the quality of the government, evident in the satisfaction that people or their friends and families receive from its services. The empirical setting focuses on the health care sector and the specific field of examination is Israeli society, which belongs to the group of Mediterranean welfare states (Gal, Reference Gal2010).

The health care sector poses major challenges to modern welfare states and their social responsibility (Arrow, Reference Arrow1963). Due to the heavy and ever increasing costs of health care services, many health care systems have faced financial crises and deterioration in the quality and quantity of services they provide (Hacker, Reference Hacker2004). As the literature reveals, this situation has triggered dissatisfaction among the citizens who utilize these services, prompting them to make informal payments for health care (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012; Cohen and Filc, Reference Cohen and Filc2017).

Such payments are a widespread phenomenon that takes different forms around the world (Gordeev et al., Reference Gordeev, Pavlova and Groot2014; Cohen, Reference Cohen2012; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mizrahi and Yuval2012; Filc and Cohen, Reference Filc and Cohen2015). Among the various definitions of this phenomenon, one of the more comprehensive and useful for the analysis of the phenomenon is that of Gaal et al. (Reference Gaal, Belli, Mckee and Szocska2006). They define it as ‘[A] direct contribution, which is made in addition to any contribution determined by the terms of entitlement, in cash or in-kind, by patients or others acting on their behalf, to health care providers for services that the patients are entitled to’ (p. 252). XXX's (XXX) typology of informal payments for health care identifies black market payments as the most discussed and critiqued type of informal payments for such services. These payments are corrupting and considered part of the shadow economy (Schneider, Reference Schneider2007; Schneider and Buehn, Reference Schneider and Buehn2007). In some cases, they involve illegal payments to health care providers to obtain higher quality care or improved access to care (e.g., paying a doctor in a public hospital to move up an appointment or receive better care). The literature asserts that the phenomenon raises numerous problems and threatens the efficiency of health care systems, as well as their equity. It can cause patients to forgo or delay care, sell assets to seek care, or lose faith in the health care system. It may also reduce its efficiency, because suppliers of health care services will pay the greatest attention to those who pay them extra. These suppliers may also try to reduce transparency and limit consumers' information about the nature and price of services (Gordeev et al., Reference Gordeev, Pavlova and Groot2014; Cohen, Reference Cohen2012; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mizrahi and Yuval2012). Thus, the prevalence of such informal payments highlights the inefficiencies of the health care system and undermines the goals and implementation of universal health care (Gaal et al., Reference Gaal, Belli, Mckee and Szocska2006: 254).

Informal payments for health care are also a recognized phenomenon in the Israeli health care system (XXX). The financing of this system and the services it provides are both public and private. Israel's four health insurance companies, to which everyone in the country belongs, are supported by government taxes and monthly fees that everyone is required to pay. In return for these taxes, Israelis receive a basket of health care services. However, Israelis can also buy additional private and semi-private plans that give them access to the use of private facilities within public hospitals and additional services such as alternative medicine and cosmetic surgery not offered in the basic basket of health care.

Although these options are considered completely formal, and indeed are often promoted and encouraged by Israeli decision-makers, scholars argue that they are blurring the differences between the private and public sectors (XXX). While the level of general satisfaction with health care services and the health care system has remained high, the level of confidence that one will receive help when needed in case of a severe illness is low (Gross, Reference Gross2004; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Barmeli-Grinberg and Mazliach2007; Brammli-Greenberg et al., Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Medina-Hartom and Belinsky2017). Recent studies also found that Israelis make informal payments for health care that are not legal and not part of the supplementary formal channels in order to obtain better services (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012; Filc and Cohen, Reference Filc and Cohen2015). Hence, (Filc and Cohen, Reference Filc and Cohen2015; Cohen and Filc, Reference Cohen and Filc2017) demonstrates how the lack of trust that Israelis have in the health care system is linked to their willingness to make informal payments for health care.

Using a national survey of 625 Israeli citizens as a representative sample of the Israeli population, this article contributes to these ideas and theories in several ways. We try to explain the normative attitudes of citizens toward the alternative provision of health care services by distinguishing between two types of parameters. One relates to how citizens think about and understand the social responsibility of the government or the scope of the welfare state. The second relates to real-world conditions such as satisfaction with health care services, participation in decision-making processes and the fairness of the health care system in providing services. We develop a rationale for these relationships based on ideas in the public management literature. In doing so, we integrate public management with the rationales related to the retrenchment of the welfare state and the alternative provision of public services. This exploration highlights the importance of perceptions about government responsibility as a main factor in shaping attitudes toward alternative political and consumer actions in the context of health care services.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the literature and the hypotheses derived from it. The third section describes the research model and methodology. The fourth section presents the findings, and the fifth section discusses the theoretical insights and contributions of the paper.

2. Citizens' satisfaction with and beliefs about socially responsible government

2.1 Satisfaction and alternative civic engagement

Strategies for obtaining services from other sources usually arise due to citizens' dissatisfaction with the government's provision of services. Such dissatisfaction may be deeply rooted in societies that have a long history of centralized control and corrupt regimes. Alternative politics then becomes an integral part of the political culture and may be considered normative (Helmke and Levitsky, Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004). In more decentralized societies, the insufficient provision of public services may result from deliberate neglect motivated by the goal of reducing government intervention in service provision (Savas, Reference Savas2000). Therefore, finding alternative sources for these services may be either deeply rooted in a culture or related to transformations in the scope and nature of the welfare state or both.

Citizens' dissatisfaction with governmental services may provoke various responses. Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) explains that when individuals are dissatisfied with a certain product, they might choose either the voice option, meaning they will demand better outcomes, or use the exit option and simply leave the firm. The choice between the two options depends on the degree of loyalty to the firm. As the degree of loyalty increases, the chance that the voice option will be chosen also increases, and vice versa. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that there will be a negative correlation between trust and the use of alternative channels or modes of health care. While exit is usually an individual action, voice, to be effective, requires collective action (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1993). As already explained (Dowding et al., Reference Dowding, John, Mergoupis and Van Vugt2000; Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2008, Reference Dowding and John2012), scholars distinguish between individual voice – individual complaints following poor service – and collective voice.

Lehman-Wilzig (Reference Lehman-Wilzig1991) suggests that there may be a strategy between exit and voice that Hirschman missed in his seminal work. Such a strategy, which he terms quasi-exit, includes bypassing the traditional system of governmental services, and establishing alternative social and economic networks to offer what the official political system cannot, or will not, provide. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Mizrahi and Yuval2012) and Cohen and Filc (Reference Cohen and Filc2017) argues that the strength of citizens' preferences for the extra-legal or illegal self-provision of services depends primarily on their satisfaction with the services provided by the government.

Explaining and measuring citizens' attitudes toward the alternative provision of services may be very tricky because the formal status of such services is vague, and people may interpret them in various ways. For example, if the government does not treat informal payments as a criminal offense, citizens may regard them as normative, although they are not legal. It is therefore important to evaluate how such modes of behavior are viewed in a given society and whether people understand that these practices are less desirable from normative and legal perspectives.

Studies show that Israeli citizens will not openly state their willingness to engage in illegal activities such as offering bribes. This reluctance implies the existence of a moral barrier that inhibits Israelis from identifying themselves with illegal behavior (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mizrahi and Yuval2012). Nevertheless, they are willing to make informal payments for health care, arguing that such payments already exist in the system. Some may even claim that their use is a normative strategy (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012). The fact that people are more willing to engage in black market activities when it comes to health care than in other areas illustrates the special nature of health care. The importance attached to good health, and the fear and uncertainty surrounding health problems, intensifies people's willingness to operate on the margins of the law.

2.2 The process of governing: fairness and participation in decision-making

The relations between citizens and governments have a great deal to do with the process of governing rather than solely with the outputs governments provide. At the core of the social contract between citizens and government is the expectation that the government will treat citizens fairly and be responsive to their needs (Rawls, Reference Rawls1971; Downs, Reference Downs1957). In this regard, prior expectations have a strong and consistent influence on future expectations (Hjortskov, Reference Hjortskov2018). The public management research incorporates these ideas in mechanisms of participation in decision-making and mechanisms that guarantee equal treatment and ethical behavior (King et al., Reference King, Feltey and O'Neill1998; Irvin et al., Reference Irvin, Renée and Stansbury2004). We expect that when citizens are not included in decision-making, they will be less satisfied with the government. In contrast, the desire for fair treatment will motivate citizens to favor the government's role in providing public services rather than promoting alternative methods.

To support this argument, we suggest that the management of public agencies is largely a reflection of the democratic values that various stakeholders believe are important for the quality of the administrative process (King et al., Reference King, Feltey and O'Neill1998). Examples of these values include perceived accountability and transparency, ethics and morality, feelings of just representation and absence of discrimination, and a sense of participation in decision-making. Accountability and transparency provide an indication as to the internal mechanisms of managerial self-criticism and willingness to improve existing processes and procedures. Accountability refers to the duty of governments and public officials to report their actions to their citizens, and the right of the citizens to take steps against those actions, if they find them unsatisfactory (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007).

In addition, many studies agree that a well-functioning public administration system also encompasses ethical standards, integrity, fair and equal treatment of citizens as clients and appropriate criteria for rewarding public servants (DeLeon, Reference DeLeon1996; Bovens, Reference Bovens2007). Perceptions about the democratic values of the public sector also include a feeling of being represented in governmental and administrative organizations, a sense that services are provided without discrimination, and the public's belief that it has reasonable access to decision-makers and decision-making junctures in the administrative process. In other words, the satisfaction that citizens have with the public system is largely a function of its managerial qualities, its various agencies and organizations, public personnel and overall climate and culture.

In addition, and based on the theory of the relationship between bureaucracy and democratic participation (Mosher, Reference Mosher1982), we maintain that perceptions about the democratic values of the public sector are related to the managerial quality of the public sector as citizens see it. This relationship is also based on the idea of authentic participation and the work of Irvin et al. (Reference Irvin, Renée and Stansbury2004) and King et al. (Reference King, Feltey and O'Neill1998). One might argue that the more people know about how public services are organized and supplied, the more likely they are to have a negative view of it. However, King et al. (Reference King, Feltey and O'Neill1998) maintain that when people are deeply involved in practical administrative processes of any kind, they acquire a better understanding of and a more realistic perspective about the specific processes, difficulties and dilemmas that the public sector and its officials face in their daily activities. As a result, these citizens will tend to be more satisfied with public services simply because they get to know them better and appreciate the effort invested in supplying them to the public. In the same vein, increased transparency and accountability, higher standards of ethics and morality, better representation at major decision-making junctures and a reduction in discrimination in the administrative and procedural process may also affect the satisfaction of citizens. Distancing citizens from decision-making centers may lead to more alienation from and disaffection with public administration. In contrast, bringing customers closer to public institutions provides them with a more realistic understanding of and appreciation for the complexity and efforts invested in making bureaucracy work properly.

Hence, we hypothesize that when the process of governing reflects fair and equal treatment, citizens will most likely trust the government and believe that the alternative provision of services is less preferable than having the government provide these services to all. We also expect that participation in decision-making will increase citizens' satisfaction with health care services.

2.3 The socially responsible government

When forming their attitudes about the alternative provision of health care services, citizens draw on their perceptions about the requirement of a socially responsible government to provide such services. Broadly understood, this responsibility is usually analyzed in the context of welfare state regimes. One of the various models of the welfare state is called the southern model of the Mediterranean welfare state (Leibfried, Reference Leibfried, Ferge and Kolberg1992; Castles, Reference Castles1995; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996). Gal (Reference Gal2010) maintains that there is an extended family of Mediterranean welfare states consisting of eight different nations, some of which have been ignored in the ongoing discussion of this model. He stresses the common nature of the labor market that has developed within them. Specifically, labor market rigidity and segmentation that distinguishes between insiders, who are protected within a formal economy, and outsiders, who comprise a relatively unprotected temporary or informal segment of the labor market, are features often evident in Mediterranean welfare states. These factors have contributed to the emergence of significant shadow economies in these nations, with obvious implications both for the protection of workers within these sectors of the labor market and for the state revenues crucial for financing the welfare state (Gal, Reference Gal2010: 288). These shadow economies continue to play a much larger role in Mediterranean welfare states than in other welfare states. Indeed, there are several indications that the extra-legal and illegal alternative provision of health care services does exist in other Mediterranean countries besides Israel, such as Greece and Turkey (Liaropoulos and Tragakes, Reference Liaropoulosa and Tragakes1998; Adaman, Reference Adaman2003; Mossialos et al., Reference Mossialos, Allin, Karras and Konstantina2005; Tatar et al., Reference Tatar, Ozgen, Narcı, Belli and Berman2007). Moreover, Cunningham and Sarayrah (Reference Cunningham and Sarayrah1993) identified the concept of Wasta, which they define as a ‘hidden force behind the Mediterranean society’, as an explanatory variable of decision-making in Mediterranean societies. If one is close with the group in power, s/he will receive preferential treatment, including health care services.

It follows that in such societies, there is a limited sense that the government has responsibility for its citizens' social welfare. In such a climate, it is not surprising that the public will look for other ways to obtain health care services. We can therefore expect that the belief in the government's social responsibility will be negatively related to supportive attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care services.

However, we should bear in mind that this impact will most likely materialize when citizens are dissatisfied with the health care services offered to the public and have little trust in the government. Therefore, in addition to the direct relationships mentioned above, we also hypothesize that beliefs about the government's social responsibility mediate and/or moderate the relationships between citizens' satisfaction and supportive attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care services for several reasons. First, citizens' dissatisfaction may damage their belief in the government's social responsibility, which then increases their support for seeking alternative sources themselves, thus producing a mediating effect. Second, when citizens' dissatisfaction leads them to prefer alternative sources of health care, the fact that they believe that the government should be responsible for providing high-quality health care intensifies their disappointment with the government and hence strengthens their support for alternative sources of such services. We thus hypothesize that as beliefs about the government's social responsibility strengthen, the negative relationship between citizens' satisfaction and seeking alternative sources of health care services intensifies.

3. Research model and hypotheses

Figure 1 presents the research model. It depicts the relations between five variables: supportive attitudes toward alternative health care services, satisfaction with health services, perceptions of socially responsible government, perceptions about the existence of participation in decision-making and perceptions about the fairness of the government's provision of services. We also added control variables such as level of trust in the public health care system and individual socio-demographic characteristics. Figure 1 illustrates both the direct relations between the independent variables and the dependent variable, and the mediating and/or moderating relations.

Figure 1. The research model.

Based on the literature review and the rationales developed in the previous section, we posit that:

H1: Supportive attitudes toward alternative health care services are directly and negatively related to satisfaction with health care services.

H2: Supportive attitudes toward alternative health care services are directly and negatively related to perceptions of socially responsible government.

H3: Perceptions of socially responsible government mediates the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services.

H4: Perceptions of socially responsible government moderates the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services. The greater the sense of the government's responsibility, the stronger the negative effect of satisfaction with health services on alternative health care services.

H5: Satisfaction with health services mediates the relationship between perceptions of participation in decision-making and alternative health care services.

H6: Perceptions of fair and equal treatment in the government's provision of services are directly and negatively related to alternative health care services.

3.1 Israeli citizens' attitudes and the health care system

The Israeli health care system includes elements that are both public and private. By law, all Israeli citizens are required to belong to one of four national health insurance companies and must pay for membership in them. In addition, everyone must pay a national health care tax to the government. In return for these taxes, the government provides a basket of health care services and approved medications. In addition to these services, people can also buy additional private health care insurance from the national health insurance companies that give them access to medications and services that are not included in the basic health care coverage.

Furthermore, the provision of health care services is also both public and private, as the government, the city, the non-profit sector and the private sector all own health care facilities. The Ministry of Health is responsible for the planning and supervision of health care and for preventive medicine, but it also runs hospitals and psychiatric services. The health insurance funds administer and provide almost all primary and secondary care, and they finance (and sometimes provide) hospital services. Voluntary non-profit organizations also run hospitals and provide emergency care. City councils are responsible for preventive care and public health services, and some even run hospitals. The private sector provides out-patient treatment, laboratory testing and medical imaging, and hospitalization (mostly following elective surgical procedures).

The hospitals incorporate these private and semi-private initiatives into their routine activities via three main mechanisms: Sharap (an acronym for private medical services), Sharan (an acronym for additional medical services) and private facilities within the public hospitals. Sharap is a system by which patients may choose their physician in a public hospital by paying an additional fee. Sharan is a system by which public hospitals sell services not included in the public basket of services to the health insurance funds, to private insurers, or to individuals. As yet another source of income, public hospitals and the health insurance funds have begun to offer private services – and even private hospitals – that provide profit-making services (among them, plastic surgery clinics, private obstetric wards and private surgery for tourists).

These developments have begun to blur the differences between the private and public sectors (Filc and Cohen, Reference Filc and Cohen2015). The public health insurance companies sell private insurance for procedures performed in private hospitals by physicians who are paid on a fee-for-service basis but who are also salaried employees in public hospitals. In addition, two of these companies provide private dental care and own for-profit hospitals that specialize in elective surgical procedures.

Since 1995, a series of surveys have monitored public opinion about the level of services and the performance of the health care system in Israel (Gross, Reference Gross2004; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Barmeli-Grinberg and Mazliach2007; Brammli-Greenberg et al., Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Medina-Hartom and Belinsky2017). In 2019, Brammli-Greenberg et al. (Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Medina-Hartom, Belinsky and Yaari2019) depicted the ‘complex picture’ of the Israeli public's experience. On one hand, the level of general satisfaction with the health care system and the services it provides has remained high. On the other hand, the level of confidence that one will be able to obtain the services needed in case a severe illness is low. One of the troubling findings of this survey is that 6% of the respondents said that they had felt the need to make a discreet, informal payment for preferential health care services in the previous five years. A multivariate analysis controlling for background variables that they conducted found that those who had undergone surgery were more likely to report such a need.

These findings are open to various interpretations. On one hand, this study suggests that of the 6% who make such payments (far lower than reported in previous decades), 20% say they do so to obtain a service not included in the basic basket of services. Hence, one may claim that if a service is not included in the basket of services, there is nothing illegal about paying for it out of pocket. In contrast, 50% of those who reported that they made the payment to get better care may reflect a willingness to engage in illegal behavior. Moreover, one may also question the degree to which the respondents differentiate between legal supplemental payments and actual black market medicine. Finally, the survey shows that as much as 60% of the population are concerned that they will not receive service from their health care plan when they need it, meaning that we could expect much more discrete, informal, or illegal payments. The fact that this is not the case might imply that Israelis are rather unlikely to make illegal payments even to obtain medical treatment.

On the other hand, others may claim that people usually tend to hide illegal behavior, so the number of people who actually use such practices will always be higher than reported in surveys. Therefore, decision-makers should not underestimate this phenomenon. This point is especially important given that these numbers are in line with other studies (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mizrahi and Yuval2012; Filc and Cohen, Reference Filc and Cohen2015; Cohen and Filc, Reference Cohen and Filc2017) and accord with the fact that the alternative provision of health care services is not a new phenomenon in Israel (Shvarts et al., Reference Shvarts, Leeuw, Granit and Benbassat1999). Hence, 84% of Israelis believe that without a direct connection to the centers of power in the HMOs and hospitals, they will not be able to obtain appropriate medical treatment in case of serious illness (Brammli-Greenberg et al., Reference Brammli-Greenberg, Medina-Hartom, Belinsky and Yaari2019).

Indeed, the debate between Filc and Cohen (Reference Filc and Cohen2015) and Chinitz and Israeli (Reference Chinitz and Israeli2016) clearly reflects these two contradictory approaches. The former claim that the advent of increasing privatization of Israeli health care has undermined the ability of the National Health Insurance law to fulfill its promise, and that blurring the boundaries between private and public health care strengthens black market practices in Israel. Chinitz and Israeli (Reference Chinitz and Israeli2016) have taken a more sanguine view, arguing that there has not been a significant decline in the public financing of medical care as Filc and Cohen claimed. Moreover, Chinitz and Israeli also argue against focusing on informal payments and the decline in the financing of public health care because they are minimal.

This debate will probably remain unresolved in the near future, and one should interpret the findings of these studies accordingly. Given the public's fear as to whether the system will be there when they need it, they may have little confidence or trust in the system. In light of such concerns, should we expect to see much more black market medicine? Alternatively, are laws, regulations and enforcement disguising the public's willingness to make informal or illegal payments, making the 6% who admit to doing so actually a large number?

Kaplan and Baron-Epel (Reference Kaplan and Baron-Epel2016) report a large discrepancy between the public's preferences and the decision-makers' predicted preferences. They show that senior decision-makers in the Israeli health system are not familiar with the priorities of the public in whose name they act. Hence, decision-makers may be unaware that the public understands that the system has limits and would prefer options such as preventive or long-term care to expensive lifesaving technologies. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that citizens' lack of trust will be related to their perceptions about the health care system and their willingness to make informal payments for health care. Indeed, Filc and Cohen (Reference Filc and Cohen2015) and Cohen and Filc (Reference Cohen and Filc2017) has established such a link in Israel.

Although there is research documenting the effect that perceptions of health care workers' regarding their role have on enhancing patients' sense of trust in the Israeli health care system (Monas et al., Reference Monas, Toren, Uziely and Chinitz2017), there are relatively few studies of trust in the Israeli health care system overall (Chinitz, Reference Chinitz2000, Reference Chinitz2004; Chinitz et al., Reference Chinitz, Galili, Alster and Israeli2001; Mizrahi et al., Reference Mizrahi, Vigoda-Gadot and Cohen2009). A recent study using a representative sample of 820 Israeli respondents with identical health care plans reveals that when people sense that they have control over their health and the ability to participate in decisions, they have more trust in decision-makers (Gabay, Reference Gabay2015). Nevertheless, some Israelis feel that they cannot rely on the state's welfare services. According to an OECD survey (2018), Israel is second only to Mexico in the lack of trust of its citizens in their ability to obtain social services from the government.

4. Method

4.1 Sample and procedure

The sample included 625 Israeli citizens who reported their perceptions about and attitudes toward the health care system using a close-ended questionnaire. This is a procedure that has been developed and applied to similar populations in Israel since 2001. Data were collected between May and July 2015 by a random sampling method. We sampled various cities and other communities based on geographic location and the size and structure of the population. In addition, we sampled the four Israeli sick funds to guarantee that each health care organization was represented in the sample. All large, mid and small size cities were represented, as well as more rural towns across the nation. Interviewers met the participants in various locations such as public venues, governmental institutions and private homes. Anonymity was assured, and the participants were encouraged to complete the questionnaires on the spot in order to increase the return rate. Average time for completing the questionnaire was 10–15 min. However, the interviewers were instructed to be more flexible with those respondents who asked for more time. In such cases, the interviewers returned to the potential participants and collected the questionnaires in person. Alternatively, the respondents could mail or email their completed questionnaires directly to the researchers.

Of the total sample, 49% were men, 50% were married, the average age was 35.16 years (SD = 12.7) and the average years of education was 13.1 (SD = 2.03). With regard to socio-economic level, 84% were Jews, and a breakdown by income showed that 53% had a monthly income lower than the average (around $2500), 22% had an average income, and 25% reported an income higher than average. With regard to public health care services, 28% reported little use of the public health care system in the past 12 months (none to once), whereas 30% and 41% reported medium (3 times) and high level (4–5 times) use of those services, respectively. In all of these regards, the research sample was very representative of the overall Israeli population.

4.2 Measures

To explore the research hypotheses, we constructed a survey in two steps. First, we organized focus groups that included participants from different sectors and groups in Israeli society. The discussions in those groups helped us identify the major trends and decide on the items to incorporate in the questionnaire as well as verifying that the wording and phrases were clearly understood. The questions were the product of the public discourse about the health care system and the alternative provision of health care services (Mizrahi et al., Reference Mizrahi, Vigoda-Gadot and Cohen2009). We used quantitative reliability tests (Cronbach's α) to verify the validity of the first-time items and to ensure that all our respondents understood our wording. The participants indicated their responses on a scale ranging from 1 to 5.

4.2.1 Supportive attitudes toward alternative health care services

This variable was measured by three statements indicating to what extent the respondents thought that: (1) If a person needs medical treatment and is not satisfied with the services provided by the public health system, s/he has the right to make ‘a special payment’ to a physician in order to get special treatment; (2) When it is necessary, it is permissible (legitimate) to use personal contacts in order to obtain special health care services; (3) It is legitimate for physicians to increase their income through extra payments from patients of the public health system. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.66.

4.2.2 Satisfaction with health services

This variable was measured by five items indicating whether the respondents were satisfied with: (1) the quality of service of their health care service provider, (2) the quality of the management in their health care service provider, (3) the quality of the medical service provided by their health care provider, (4) the quality of the infrastructure provided by their health care provider and (5) their service provider in general. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.87.

4.2.3 Perceptions about the social responsibility of government

This variable was measured by three items indicating to what extent the respondents thought that: (1) It is the state's responsibility to provide health care services, and it should not leave it to the private sector to provide them; (2) It is the state's responsibility to narrow the gaps in health care services among citizens; (3) When the state provides health care services to citizens, it should emphasize social considerations such as equality and fairness more than economic considerations of efficiency. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.79.

4.2.4 Perceptions of participation in decision-making

This variable was measured by three items indicating to what extent the respondents thought that their service provider: (1) is interested in the public participating in the making of important decisions; (2) includes them in decision-making processes more than other public organizations do; (3) sees the public as an important factor that should participate in improving performance. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.82.

4.2.5 Perceptions of fair and equal treatment

This variable was measured by four items indicating to what extent the respondents thought that: (1) their service provider provides equal services to everyone without any distinction between people; (2) their service provider would employ any worker based on merit regardless of their race, gender, religion or ethnic origin; (3) workers in their service provider's organization are honest and impartial; (4) unethical behavior is very rare in their service provider's organization. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.76.

4.2.6 Trust in the public health system

This variable was measured by seven items indicating the extent to which the respondents trust: (1) their service provider's physicians, (2) their service provider's nurses, (3) their service provider's managers, (4) their service provider's central management, (5) their service provider in general, (6) The Ministry of Health and (7) the health care system in general. The reliability of this variable was α = 0.82.

4.3 Data analysis

We used four major strategies to test our hypotheses. First, a zero-order correlation was analyzed to assess the internal relationships among the research variables. Second, a standard multiple regression analysis was conducted to test for the effect of the independent variables on public attitudes toward redistribution. Such an examination of direct relationships is appropriate for H1, H2 and H6. This assessment was followed by multiple stepwise regression analyses to evaluate H3 and H5. Finally, the last stage of the hierarchical regression analysis examined the effect of the independent variables on the alternative provision of health care services, testing potential mediating and moderating variables.

The test of mediation was conducted following the studies of Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986), Kenny et al. (Reference Kenny, Kash, Bolger, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey1998) and Kenny's Web page on mediation (http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm). The test for moderation was conducted based on Hayes (Reference Hayes2013). A moderator is a variable that moderates the relations between two other variables in either a positive or a negative way. We conducted several moderation analyses using this method.

The analysis also controls for age, gender, income and education, which are the most relevant individual characteristics for the research setting, and helps address potential common source bias, which has become an issue for lively debate among public administration scholars in recent years (Meier and O'Toole, Reference Meier and O'Toole2013; Favero and Bullock, Reference Favero and Bullock2015). Common source bias is a systematic error variance that is a function of using the same method or source (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Simmering and Sturman2009). Meier and O'Toole (Reference Meier and O'Toole2013) argue that citizens' surveys of government performance often contain valuable information that can be gathered in no other way. Segmentation according to individual characteristics showing that these factors distribute normally can solve most of the problems in such surveys (Gormley and Matsa, Reference Gormley and Matsa2014).

5. Findings

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations and reliabilities for the research variables. As the table illustrates, most of the inter-correlations hold in the expected directions. The one exception is the positive relationship between alternative health care services and satisfaction with health services. In contrast, we expected that dissatisfied rather than satisfied citizens would tend to support the alternative provision of health care. At the same time, there is a negative relationship between perceptions of socially responsible government and alternative health care services, meaning that potentially, there are mediating and/or moderating relationships of the kind discussed above. Interestingly, the relationship between trust in the public health system and alternative health care services is not significant. In addition, contrary to our expectations, there is a positive relationship between fairness of the government's provision of services and alternative health care services. Finally, none of the inter-correlations exceeds the maximum level of 0.70, which is a good indication of the absence of multicollinearity among the variables.

Table 1. Multiple correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for the research variables (Cronbach's α in parentheses)

N = 466–625.

p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***.

Table 2 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis (non-standardized coefficients and standardized) [OLS] of the effect of the independent variables on alternative health care services. It shows that all of the independent variables tested in our research model except trust in the public health system and perceptions about the existence of participation in decision-making are related to alternative health care services. Age and education are not significantly related to alternative health care services. The explained variance (R 2) of the variables satisfaction with health services, perceptions of socially responsible government, fairness of the government's provision of services and gender is 0.09, meaning that these variables help explain only 9% of the variation in alternative health care services. These findings indicate that our research model in Figure 1 grasps the core relations among the variables only to a limited extent. Hence, our findings support H1 and H2. In addition, there is a direct significant relationship between fairness of the government's provision of services and alternative health care services, but it is positive rather than negative, as we hypothesized in H6. Later, we will discuss this finding further.

Table 2. Multiple regression analysis for the direct effect of the independent variables on alternative health care (AH) (non-standardized and standardized coefficients)

N = 466–625.

p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***.

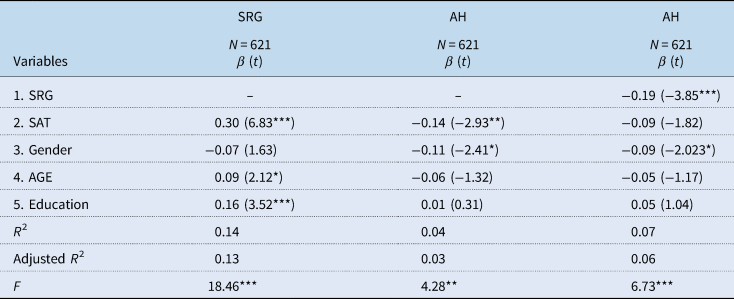

To explore these relationships further, we first conducted a mediation analysis to test H3 and H4. Table 3 shows that, as H1 posited, there is a direct, significant, negative relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services (β = −0.14). In support of H3, there is also a direct, significant, positive relationship between satisfaction with health services and perceptions of socially responsible government (β = 0.30). However, when we include both satisfaction with health services and perceptions of socially responsible government in the regression as independent variables (third column), there is a direct, significant, negative relationship between perceptions of socially responsible government and alternative health care services (β = −0.19), but the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services becomes insignificant, meaning that H1 does not hold. In this case, the explained variance is double that of the case when satisfaction with health services is the only independent variable. Most importantly, the Sobel test, which indicates the strength of the mediation, yields Z = −3.34***, meaning the mediation is intense and significant. In contrast, when testing the indirect effect between perceptions of socially responsible government and alternative health care services when satisfaction with health services is the mediating variable, the Sobel test results in Z = −0.02, meaning that mediation does not exist. Hence, our analysis supports H3.

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis (standardized coefficients) [OLS] for the mediating effect of SRG on the relationship between SAT and AH

*p ⩽ 0.05, **p ⩽ 0.01, ***p ⩽ 0.001.

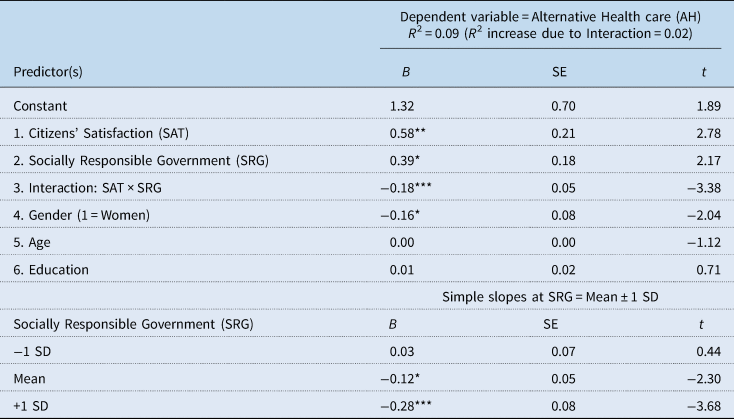

We also tested whether perceptions of socially responsible government moderates the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services. Table 4 shows that the interaction variable (SAT × SRG), which represents the moderating effect of perceptions of socially responsible government, is negative and significant (B = −0.18, p < 0.001). At the same time, the explained variance (R 2) increases by 2% due to the interaction. Together, these two findings indicate that moderation does exist, thus supporting H4. Note, however, that there is also a direct relationship between perceptions of socially responsible government and alternative health care services (B = 0.39, p < 0.05).

Table 4. Moderation analysis by SRG

N = 466–625.

p < 0.05*, p < 0.01**, p < 0.001***.

Figure 2 illustrates the moderating effect of perceptions of socially responsible government on the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services. It shows that for those who believe strongly in the social responsibility of the government, greater satisfaction reduces the support for alternative models of health care. On the other hand, for lower levels of perceptions of socially responsible government, greater satisfaction leads to a much more moderate negative change in alternative health care services. At the lower level of perceptions of socially responsible government, greater satisfaction with health services causes no significant change in alternative health care services.

Figure 2. The moderating effect of SRG on the relationship between SAT and AH.

Our interpretation of these findings builds on the centrality of the belief in the government's responsibility for social welfare as a core determinant of the relationship between satisfaction with health services and alternative health care services. The extent to which people believe that the government is socially responsible creates expectations for the provision of high-quality services. When people with high expectations become less and less satisfied with the services they receive from the government (whether it is indeed what is happening or is a distortion of reality presented to them by the media), they become disappointed and believe more in the use of alternative methods to obtain health care. Similarly, citizens who believe that the government is not responsible for the quality of public services are also those with fewer expectations about the government's role in health care. When these citizens with low expectations also become less satisfied with the quality of health care, they may become aphetic or disappointed, but do not look for these services elsewhere.

Finally, we conducted a mediation analysis to test H5. Table 5 shows that there is no direct significant relationship between perceptions about the existence of participation in decision-making and alternative health care services. However, there is a direct, significant, positive relationship between perceptions about the existence of participation in decision-making and satisfaction with health services (β = 0.37). When we include both of these factors in the regression (third column), the direct relationship for both independent variables is significant. In this case, the explained variance is more than double that of the case when perceptions about the existence of participation in decision-making are the only independent variable. Note that socio-economic status did not appear to be a factor in any of our analyses. Most importantly, the Sobel test, which indicates the strength of the mediation, yields Z = −3.45***, meaning the mediation is intense and significant. Hence, our analysis supports H5.

Table 5. Multiple regression analysis (standardized coefficients) [OLS] for the mediating effect of SAT on the relationship between PDM and AH

*p ⩽ 0.05, **p ⩽ 0.01, ***p ⩽ 0.001.

6. Discussion and conclusions

This paper explores the factors that may influence citizens' normative attitudes toward alternative methods for obtaining health care services. We question whether these attitudes depend primarily on inherent normative preferences, such as beliefs about the government's responsibility to its citizens, or on certain aspects of the reality that people experience, such as satisfaction with the quality and quantity of services as well as the fairness of public systems. This exploration may help assess to what extent the move to seek alternative sources of public services indicates deeply held beliefs or is simply a result of real-world conditions. We focus on the health care sector where the importance of such services and the complex nature of health care systems (Arrow, Reference Arrow1963) promote the search for alternative means of acquiring them.

Our analysis leads to mixed conclusions about the fundamental sources of attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. On one hand, inherent normative beliefs about the government's responsibility to its citizens relate to attitudes toward obtaining health care services from sources other than the government. On the other hand, this relationship is not strong and exists mainly in response to conditions that the public experiences. At the same time, perceptions about the fairness of health care service providers have a direct relationship with the alternative provision of health care without a link to any other variable. One might argue that the system provides a reasonable minimum level of service. However, those who want more than the minimum go outside the system to find it. On the other hand, given that these perceptions may be the result of real-world conditions and experience, this finding limits the role of ideological and normative beliefs in explaining attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. With regard to the relatively new variable of socially responsible government, we show that beliefs about the government's responsibility in this area both mediate and moderate the relationship between citizens' satisfaction with and supportive attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. The greater the responsibility of the government in the eyes of citizens to promote social welfare, the stronger the negative relationship between their satisfaction and the support for using alternatives to public health care services.

Our findings question to some degree the ability of Hirschman's (Reference Hirschman1970) model to explain the Israeli case. Hirschman's model begins with dissatisfaction, which provokes an action that could be exit or voice, depending on the costs of each and on the degree of loyalty to the organization, including the possibility of choosing to remain within the organization without complaining. Unlike in other cases, exit and voice are possible in the Israeli context. There is a growing private market in health care, and semi-private insurance plans marketed by the public health insurance companies have allowed for a significant increase in the number of surgical procedures performed within the private sector. In addition, organizations such as patient associations and groups committed to social change have been very vocal in demanding the improvement and broadening of health care services. Therefore, it seems paradoxical that people support the alternative provision of such services, which represents a quasi-exit strategy, rather than preferring exit or voice.

Our findings highlight the practical considerations and real-world conditions involved in the formation of attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. Moreover, when we incorporate rationales from the public management literature, it seems that citizens evaluate performance mainly based on their satisfaction with outcomes rather than with managerial processes. Two important variables related to the process of governing – trust and participation in decision-making – either do not influence or indirectly influence attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. We found that trust in government cannot help explain such attitudes, and that perceptions about participation in decision-making are related to such attitudes through satisfaction with the outcomes. In other words, participation in decision-making increases satisfaction with the outcomes, which then influences attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care. A third variable related to the process of governing – equal and fair treatment by the health care provider – is directly related to attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care but positively rather than negatively. Contrary to our hypothesis that fair managerial processes would motivate citizens to stick with the public system rather than legitimize obtaining services elsewhere, such processes actually weaken the inclination to remain with the public system. A possible explanation for this counter-intuitive result relates to the civic and political culture of the society. If the civic culture praises the alternative provision of public services as a means of achieving results when unfair and unequal treatment are common, citizens may view a fair public system as relatively weak and as having limited ability to achieve effective outcomes. In this case, they legitimate turning to alternative methods of obtaining services. As explained earlier, to a large extent this situation characterizes Israeli society (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012). Therefore, the variables related to the process of governing that the managerial literature emphasizes fall short in explaining attitudes toward the alternative provision of public services in societies such as Israel where alternative politics is widespread.

The paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we combine several theoretical approaches in order to evaluate whether the fundamental sources of attitudes toward the alternative provision of public services are normative perceptions about the government's responsibility or responses to actual conditions. Despite our mixed results, we conclude that practical considerations and real-world conditions have a stronger relationship to attitudes toward the alternative provision of health care services than normative perceptions do. The literature indicates that people formulate their preferences at two levels – the normative level, which is expressed by declared preferences about issues such as the scope of the welfare state – and their preferences in a given situation, which are subject to structural constraints, often termed ‘induced preferences’ (Katzanelson and Weingast, Reference Katzanelson, Weingast, Katzanelson and Weingast2005). Our findings imply that these two types of preferences are indeed categorically different and exist in different dimensions of people's minds. Furthermore, the fact that we find strong support for the welfare state implies that people are willing to turn to alternative sources for services not necessarily because they believe in the private market or favor the retrenchment of the welfare state, but, rather, due to short-term calculations aimed at improving their immediate situation.

Nevertheless, one might argue that practical considerations are combined with the public's acceptance of the fact that an entirely public system has provided the best minimum level of service that it can. If our conclusion is correct, it may have implications for the study of the welfare state and privatization. It indicates that people prefer alternative methods of obtaining public services primarily because they are forced to do so rather than because they have strong preferences for the non-governmental, private provision of such services. Therefore, those who justify privatization using support for the alternative provision of health care services as an indication of the normative preference for the private market may be on shaky ground. Theoretically, this result means that we should be very careful about making inferences about normative attitudes from behavior.

Second, we expand and extend Hirschman's seminal model further so it can help explain complex situations. People have more choices than voice and exit. Their choices depend not only on satisfaction and loyalty but also on how they perceive the responsibility of the service provider to provide high-quality services. When we refer to services that the government traditionally provides, people include their perceptions about the government's responsibility to provide these services. These perceptions are closely related to the way they perceive the role of government in general as well as their normative attitudes toward the welfare state. In other words, our analysis points to perceptions about government responsibility and attitudes toward the welfare state as another dimension that should be considered in analyzing the strategies that dissatisfied citizens adopt.

Third, and related, we show that people prioritize outcomes over managerial processes in evaluating the effectiveness of the public sector. In doing so, they are also influenced by the civic and political culture, which emerges as a significant factor in these interactions. Future research should investigate the role of this factor further.

Fourth, our analysis has managerial implications for both the public and private sector. A possible generalization of our findings implies that, when making judgments about how to obtain these goods and services, consumers consider not just prices, quality or certain personal inclinations such as loyalty, but also their perceptions about the responsibility of the provider to offer high-quality goods and services. Subsequently, consumers may be dissatisfied not only with their quality or price but also with the failure of the provider to meet its overall responsibility for the quality of its products.

The case presented here is specific with regard to time, place and policy content. Thus, we do not claim that precisely the same mechanism will operate in all circumstances. Nevertheless, although other or additional factors may influence citizens' perceptions and actions in other contexts, the analytical model presented here underscores the critical role of citizens' attitudes in health care systems. It is important to note that our findings in this paper are subject to several limitations. First, the current study examined only the Israeli case. Hence, although we may generalize from our experience to other cases, one should remember that different findings might emerge in other places around the world. As we explained, the context of the paper is one of highly centralized services where legally operating private markets barely exist. Such a situation is characteristic of Mediterranean welfare states. Moreover, the small number of prior studies on the topic forced us to develop relatively new measurements for complicated theoretical variables, with all the implications of such practices. Therefore, additional studies should be conducted on this issue. Second, due to budgetary limitations, the sample size does not allow for a more representative distribution of the population, meaning that a larger sample might have produced more significant findings. Third, our data do not include information about the status of the participants' health, which might influence their attitudes towards the health care system. Fourth, despite our attempts to minimize the problem, common source bias remains a potential issue.

Identifying weaknesses is the first important step toward formulating new research questions (Ioannidis, Reference Ioannidis2007: 328). Hence, this study has highlighted several findings and insights for future research. In this regard, more studies that focus on other experiences around the world may increase our knowledge about alternative models of public health care, as well as their relationship to beliefs about the social responsibility of governments. The integration of quantitative and other qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews and focus groups would be a good basis for these future studies.