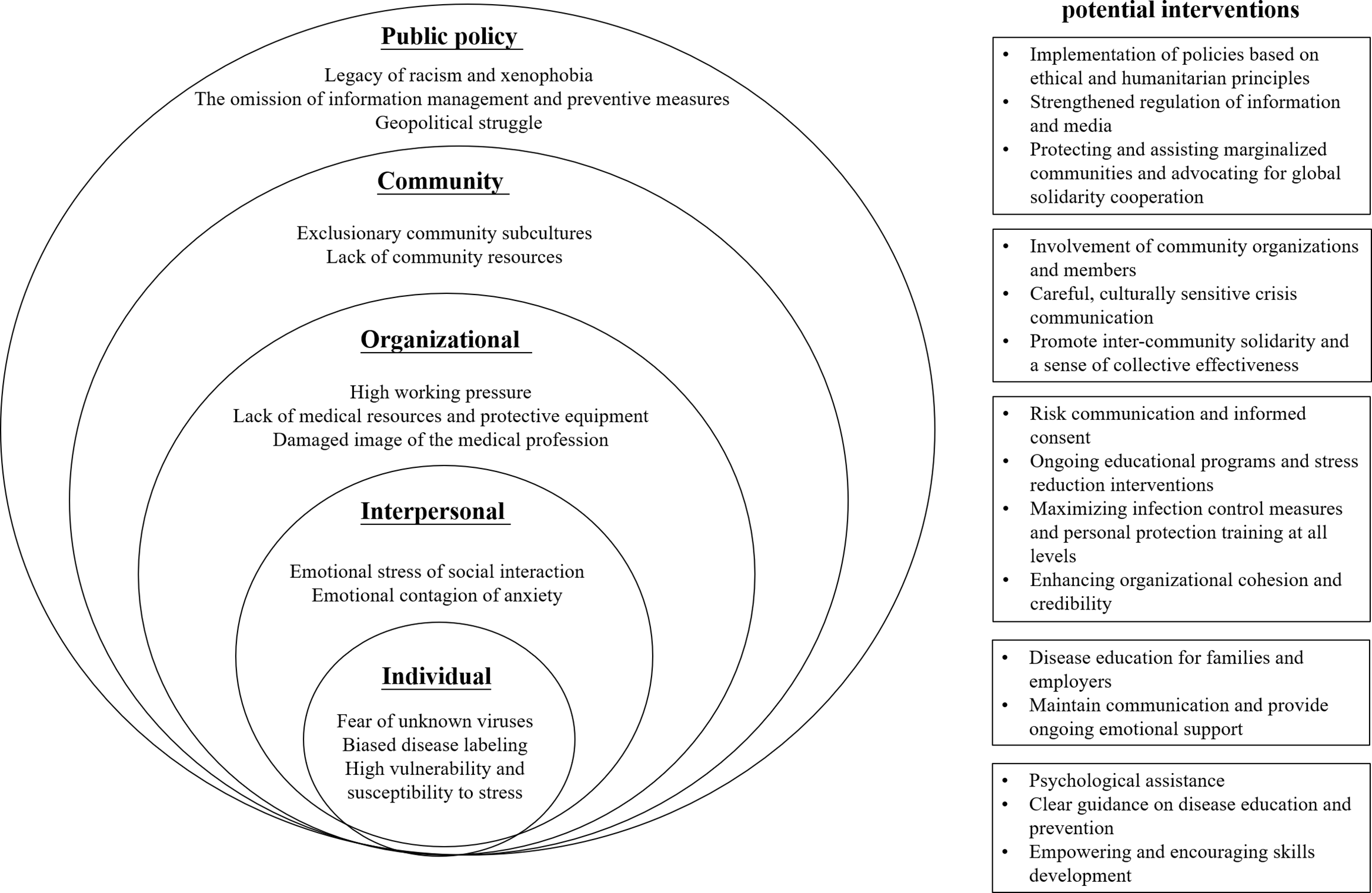

To the Editor—The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic has sparked social stigma and discrimination against people from certain regions, countries, occupations, or ethnic groups, as well as anyone perceived to have been in contact with the virus. Research on infectious diseases has suggested that stigma presents barriers to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, increasing physical suffering and psychological burden on the individual who has been victimized in the process. Reference O’Neill, Irani and Siewe Fodjo1 To describe the stigma that exists and its impact in the context of COVID-19, we provide a taxonomy by employing a socio-ecological model that categorizes the broad lessons learned from communicable diseases into the following levels: intrapersonal, interpersonal, community, institutional, and public policy. Reference Stokols2 Approaches that address stigma at each level will inform efforts to reduce and control stigma during a pandemic (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The social–ecological taxonomy of infectious disease stigma research.

The socio-ecological theory holds that individual factors such as knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and skills are malleable, constructed with constant feedback from the social environment. Reference Rüsch, Angermeyer and Corrigan3 During an epidemic, people develop a relatively consistent set of risk perceptions through perceived likelihood of infection, personal susceptibility, and disease severity. However, they exhibit individual emotional differences in decision making, especially when confronted with highly uncertain risks. Reference Adhikari, Kaehler, Raut, Marahatta and Ggyanwali4 Existing studies utilizing socio-ecological theory have demonstrated the effectiveness of education as an intervention tool. It is critical that local public-health risk assessments be continuously improved and that they provide real-time, context-sensitive guidance for clinical practice. Reference Heymann5 Furthermore, psychological assistance is indispensable for all people due to different vulnerabilities and susceptibility to stress. Service providers need to understand the experience and meaning of the disease to the person and to reframe the discourse by empowering the public.

According to social identity theory, the behavioral decisions of potentially stigmatized groups can be influenced not only by personal motivations and skills but also by fear of losing social ties. Reference Pryce, Mableson and Choudhary6 COVID-19 has shown the power of continuous human-to-human transmission, so family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and acquaintances may show euphemistic rejection and ostracism in words and actions, and the expected stigma may make people feel a diminished social identity. Reference Zhao, Zhuang and Ran7 Significant social relationships, under complex changes of the COVID-19 epidemic, need to be constantly adjusted and adapted to bridge differences and enhance communication. Support groups, specifically for those who are quarantined, can provide a validating, empowering experience, and a successful interactive experience may encourage people against the anticipated stigmatizing reactions.

In responding to a major public crisis, medical personnel are the most important organizational force, but even well-trained professionals subscribe to stereotypes, especially if they work in high-risk areas. Reference Engelbrecht, Rau and Kigozi8 During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs have been heroically at the forefront of the fight against the disease, but many healthcare providers experience considerable stigma and loneliness. Providing direct patient care to infected patients or those who have survived infection may initiate emotional, ethical, and cultural tensions and conflicts for healthcare providers. Reference Chen, Liang and Li9 It is the responsibility of the organization to create a supportive atmosphere of cohesion and effectiveness and to build a culture of organizational resilience. Importantly, HCWs can be motivated if risks are carefully managed and their professionalism is recognized and affirmed by public figures and the population.

Within a given geographical area, infectious diseases coincide and interact with multiple social concerns, and susceptibility to infectious diseases will expand for members of communities living in poverty with high population density and limited access to health care and other resources. Communities that were once marginalized are at risk of further disenfranchisement. Reference Stein10 Given specific networks and subcultures within the community, interventions addressing community stigma need to be adopted in a respectful manner. Community-based organizations and civil society organizations are vital stakeholders, and they should be integrated into a community-based model to eliminate discrimination. In addition, residents may be driven by a greater sense of connectivity and solidarity to engage in collective action to address community issues.

Examining the development of the outbreak narrative, stigma can be regarded as a form of “structural violence,” with policies having profound social roots and politics, economic, and ethnocultural contexts. If not applied wisely, the policy burden associated with pandemics can affect the most vulnerable populations, can exacerbate existing inequalities, and can even contribute to more abuse and violence on a global scale. The political exploitation of public policies against global contagion in some countries and regions sparks social comparisons and devaluations of other groups, which make innocent people suffer stagnation because of their nationality, ethnicity or other reasons. Reference Hirschberger11 Policy makers and health authorities should be alert to the rise of prejudice and stereotyping of particular societal groups, and they should continually review possible omissions in the way laws, social services, resource allocation, and the justice system are structured for restoring the trust of marginalized communities. Notably, globalization has resulted in international responsibility, and the challenge of COVID-19 requires sustained attention and a strengthened commitment to international equity and inclusion.

Overall, communicable diseases are generally prone to stigmatization, and stigma poses significant challenges to infected individuals, families, social networks, health networks, institutions and communities. In the specific context of a pandemic, stigma cannot contain the virus. Every level is important, and the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic will only be won when the world forms a community of mutual recognition, respect, and reciprocity toward a common destiny.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This work was supported by National Precision Cooperation Project (grant no. 2017YFC0910000) and by the Clinical Research Project of Shanghai Mental Health Center (grant no. CRC2017YB03).

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.