On December 30, 2020, as healthcare personnel (HCP) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination was being initiated in the United States, the infection prevention team of an acute-care hospital (hospital A) in Santa Clara County, California recognized a cluster of 22 emergency department (ED) HCP who worked on December 25 and then tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 after becoming symptomatic. The hospital notified Santa Clara County Public Health Department (SCCPHD) and California Department of Public Health (CDPH) on January 3, 2021. CDPH, SCCPHD, and hospital A requested assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to investigate potential routes of transmission, to identify infection prevention and control (IPC) gaps, and to recommend strategies to mitigate future risks.

Methods

A probable case was defined as a positive SARS-CoV-2 test by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) occurring in (1) hospital A HCP assigned to the ED (referred to as ED HCP), (2) HCP (referred to as ED-linked HCP) or patient (referred to as ED patient) who spent at least 15 minutes in the ED in the 14-day period prior to infection (symptom onset date or positive SARS-CoV-2 test specimen collection date, if asymptomatic), or (3) HCP or patient with an epidemiologic link to a confirmed case (eg, present on the same unit at the same time) provided the timing of the infection fell between and including December 11, 2020, and January 9, 2021. Notably, this date range represents a full incubation period (14 days) before and after December 25. Confirmed cases met the probable case criteria and had a SARS-CoV-2 isolate that matched the outbreak sequence; that is, they differed by ≤3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) according to whole-genome sequencing (WGS).

We reviewed California Reportable Disease Information Exchange (CalREDIE), California Connected system (CalCONNECT), and testing records of hospital A to identify SARS-CoV-2 infections among HCP and ED patients. Prior to the identification of this cluster, hospital A had been offering voluntary weekly PCR testing to asymptomatic HCP with low uptake. Following outbreak identification, hospital A offered PCR testing every 3 days between January 1 and February 28 to all HCP who were in the ED on December 25. All hospital HCP, including ED HCP who did not work on December 25, were encouraged to undergo testing for SARS-CoV-2. All patients admitted for inpatient treatment were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission, and those who were in the ED between December 25 and December 30 additionally received serial testing every 3 days during their hospitalization. Patients who presented to the ED on December 25 between 9:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. and were not admitted were offered SARS-CoV-2 testing after identification of the outbreak. The Santa Clara County public health laboratory performed WGS.

Using staffing rosters, we determined dates when infected ED HCP had worked between December 11 and January 9 and were infectious, defined as during 2 days prior to symptom onset and within 10 days after symptom onset.

The hospital IPC team conducted a survey between January 5 and January 11 of all ED and ED-linked HCP who had worked on December 25. The survey assessed potential exposures during their December 25 shift, previous exposures during December, observations on shifts between December 18 and December 25, and COVID-19 vaccination status. A team of federal, state health department, and county health department staff including infection preventionists, an industrial hygienist, medical officers, and epidemiologists conducted 2 onsite observations of clinical and nonclinical work areas and interviewed unit managers, infection preventionist, occupational health manager, facilities manager, and the facility’s management team. We used these results to describe IPC and industrial hygiene policies and practices for COVID-19 prevention in hospital A, including entry screening, physical distancing, personal protective equipment use, case investigation, contact tracing, work restriction, airflow, and ventilation.

This activity was reviewed by the CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy (eg, 45 CFR part 46, 21 CFR part 56; 42 USC §241(d); 5 USC §552a; 44 USC §3501 et seq).

Results

We identified 17 confirmed cases and 82 probable cases among HCP and 6 confirmed cases and 12 probable cases among patients (Fig. 1A). COVID-19 symptoms were reported by 86 (87%) of 99 HCP cases, and 1 individual who worked in the ED died due to COVID-19. Among all 311 ED HCP, 53 (17%) were cases; clinical and nonclinical HCP were similarly affected. Isolates from 19 HCP and 6 patients were sequenced, and with the exception of isolates from 2 HCP, all were ϵ (epsilon or B.1.427) variant and within 3 SNPs. This variant sequence had not been observed in an outbreak among community cases at the time of this investigation.

Fig. 1. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 cases in the Emergency Department (ED) of hospital A, December 11, 2020–January 9, 2021. (A) SARS-CoV-2 cases in the ED of hospital A from December 11, 2020, to January 9, 2021 (N = 99 HCP and 18 patients). (B) Distribution of ED HCP cases by date of working in the ED while infectious with SARS-CoV-2 (N = 27). (C) ED HCP cases by days worked in the ED, relative to their COVID-19 symptom-onset date (N = 27).

Between December 27 and January 9, 98% of 146 ED and ED-linked HCP who worked on December 25 were tested for SARS-CoV-2, compared to 69% of 237 ED HCP who did not work on December 25, and 44% of 2,438 other HCP. Our review of HCP location, timing, and staffing data did not reveal any single HCP, patient, or particular event that was linked to the majority of HCP and patient cases.

In total, 27 ED HCP worked while potentially infectious: 2 days before symptom onset (n = 20), 1 day before symptom onset (n = 15), on the same day as symptom onset (n = 10), 1 day after symptom onset (n = 5), 2 days after (n = 4), or 3–10 days after symptom onset (n = 3) (Fig. 1B and 1C). Also, 9 or more infectious HCP worked on each day from December 25 to December 27. We identified 12 calendar days (54 person days, defined as any day when a potentially infectious HCP worked, regardless of shift length) between December 11 and January 9 when at least 1 infectious HCP worked in the ED on the same day as a future HCP or patient who became infected within 14 days. In addition, 6 ED HCP tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between December 4 and December 10 (not included in case definition), at least 1 of whom worked while infectious during this period.

Among 87 ED patients seen between December 25 and December 30 and admitted with a negative SARS-CoV-2 PCR test on admission, 1 (1%) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test within 2 days, and 4 (5%) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test within 3–14 days. Among them, 2 were admitted on December 25 and 3 were admitted between December 26 and December 30. Of 69 ED patients seen on December 25 between 9:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. who were not admitted and who did not have known SARS-CoV-2 infection on presentation, 13 (21%) tested positive from December 31 through January 5, 35 (49%) tested negative, and 21 (30%) were lost to follow-up. Patients seen in the ED outside this period were not followed.

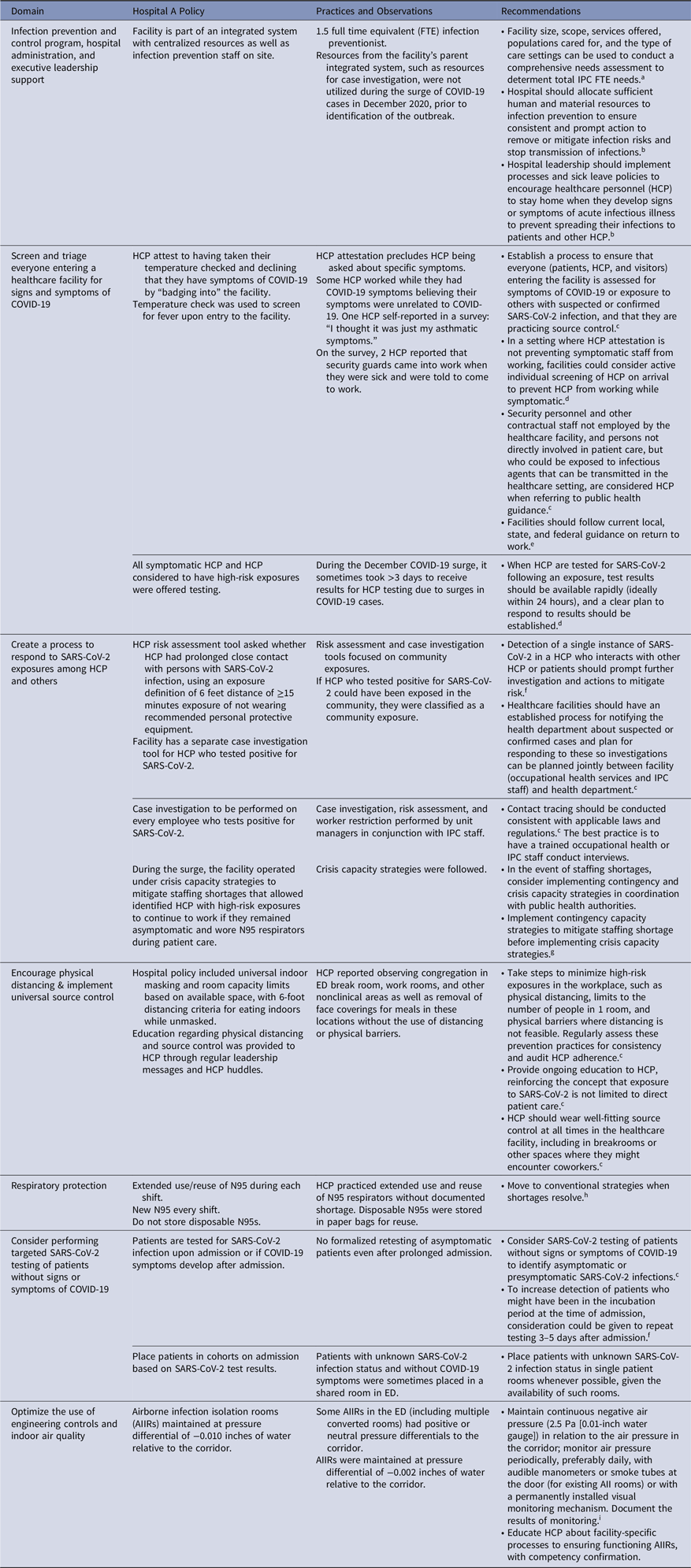

We identified multiple IPC gaps in hospital A (Table 1). In total, 118 (81%) of 146 HCP who worked in the ED on December 25 responded to the survey. Overall, 72% of HCP had received a first dose of an mRNA vaccine but no HCP had been fully vaccinated. HCP reported working while symptomatic or observing others who worked while symptomatic, citing difficulties in attributing symptoms to COVID-19. HCP noted congregating in the ED break room, work rooms, and other nonclinical areas as well as removing face coverings for meals without physical distancing or barriers. HCP entry screening relied upon an automated temperature check station and a protocol for attesting no COVID-19 symptoms by “badging in” for work. Hospital A’s exposure risk assessments for HCP in early December did not identify all possible workplace exposures. Exposed HCP were permitted to continue working if they remained asymptomatic, in accordance with California executive order no. N-27-20.

Table 1. Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) and Industrial Hygiene Practices, Observations, and Recommendations, Emergency Department (ED) of Hospital A, December 2020–January 2021

a See Bartles R, Dickson A, Babade O: A systematic approach to quantifying infection prevention staffing and coverage needs. Reference Bartles, Dickson and Babade10

b See Core infection prevention and control practices for safe healthcare delivery in all settings—recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) 2017. 11

c See Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. 2

d See Interim guidance on testing healthcare personnel for SARS-CoV-2. 12

e See Interim guidance for managing healthcare personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection or exposure to SARS-CoV-2. 13

f See Responding to SARS-CoV-2 infections in acute care facilities. 14

g See Strategies to mitigate healthcare personnel staffing shortages. 15

h See Strategies for optimizing the supply of N95 respirators. 16

i See Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. 17

Discussion

A large outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 occurred in the ED of an acute-care hospital. During December 2020, the daily incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Santa Clara County was 68 per 100,000 population, 1 representing potential opportunity for SARS-CoV-2 introduction into a healthcare facility. WGS results were available for 25 cases; 23 of these matched within 3 SNPs, suggesting that a single introduction might have precipitated subsequent transmission events among ED patients and HCP. We were unable to fully evaluate all potential exposures and events that could have contributed to the spread of SARS-CoV-2. However, our investigation did demonstrate that within-facility transmission could have started in early December. During mid-December and early January, we identified 12 calendar days in which a total of 27 HCP worked in the ED while infectious on the same day as a future HCP or patient case who developed symptoms or tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 within 14 days after that exposure. This finding suggests many opportunities for transmission contributing to the later increase in cases. We recommended that there should be a process to ensure identification of everyone entering the facility with COVID-19 symptoms or exposure to others with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1). Detection of a single case of SARS-CoV-2 in an HCP should prompt further actions, such as contact tracing to mitigate risk to other HCP, patients, and visitors. Engineering and administrative controls such as ensuring adequate ventilation in break rooms, limiting room capacity, and adhering to recommended work exclusions are vital to preventing higher-risk exposures between HCP. 2

This study had several limitations. The uptake of SARS-CoV-2 testing at the hospital was incomplete, and the survey was only distributed to HCP who worked on December 25. However, we incorporated data from state surveillance systems to identify all SARS-CoV-2 diagnoses among ED HCP and identified potential transmission chains beyond HCP who worked on December 25. SARS-CoV-2 isolates from before December 26 were not saved and therefore could not be sequenced for comparison with outbreak cases. Similarly, hospital A limited case finding to ED patients seen on December 25, so we were not able to identify SARS-CoV-2 infections among ED patients seen on other days or lost to follow-up. By contrast, patients who were asymptomatic were not tested for SARS-CoV-2 at the time of ED presentation, causing potential misclassification of patient cases. The scope of IPC gaps may have also been underestimated because HCP symptoms and IPC practices were self-reported after the identification of the outbreak. Despite these limitations, observed IPC lapses and the large number of HCP who worked while potentially infectious strongly suggest multiple opportunities for transmission within the ED in December.

SARS-CoV-2 transmission between HCP is a well-known driver of acute-care hospital outbreaks. Reference Schneider, Piening, Nouri-Pasovsky, Kruger, Gastmeier and Aghdassi3–Reference Paltansing, Sikkema, de Man, Koopmans, Oude Munnink and de Man6 Despite HCP vaccination, breakthrough infections via symptomatic and asymptomatic vaccinated HCP can still contribute to transmission to patients and other HCP. Reference Hetemäki, Kääriäinen and Alho7 Gaps in physical distancing and source control in non–patient-care areas, delays in testing, and HCP working while infectious have previously been identified as contributing factors. Reference Schneider, Piening, Nouri-Pasovsky, Kruger, Gastmeier and Aghdassi3,Reference Klompas, Baker and Rhee8 Our investigation reinforces the importance of monitoring and ensuring HCP adherence to well-fitting masks for source control and physical distancing, especially in common work and break areas. Reference Richterman, Meyerowitz and Cevik9 This aspect may be especially challenging and important during holiday periods when hospital staff are accustomed to engaging in celebratory activities and interacting socially. Early identification of risk and work restriction can prevent further transmission: hospitals should have systems to accurately detect and respond to HCP exposures and should be prepared to notify and follow the recommendations of public health authorities. 2

During surges of SARS-CoV-2, efforts to fully implement vaccination and promote IPC practices are paramount in mitigating within-facility transmission. This outbreak occurred as HCP vaccination was being initiated in the facility. Our findings could additionally inform healthcare facilities’ response to novel emerging respiratory pathogen or an emerging variant that evades vaccine-induced immunity (eg, the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant).

Acknowledgments

We thank hospital A for sharing data on testing, HCP survey, and staff roster; for providing feedback on the manuscript; and for their care of patients throughout the pandemic. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.