INTRODUCTION

The primary principle of the restitutive or reformative penal system is to ensure that punishment ultimately reforms the guilty and makes them return to society as functional members. The social life of released prisoners is broadly a reflection of a host of social and legal institutions and practices at work of any given society. Concepts such as reintegration, re-entry and rehabilitation assume significance in this context where the post-release life of the ex-offender is analysed, especially in connection with concerns of recidivism and maintenance of law and order. Despite its centrality in the academic and policy realms, the social reintegration of ex-offenders remains one of the most elusive and under-studied topics in criminology and other branches of social sciences. As the literature on the reintegration of released prisoners from across countries suggests, this process is multidimensional and involves many actors, including the offenders themselves, prison and other legal institutions, and wider society.

The concept of reintegration, especially concerning ex-offenders, is fraught, as scholars have often pointed out that most of these discussions occur in a theoretical vacuum (Garland and Wodahl Reference Garland, Wodahl, Crow and Smykla2014; Maruna, Immarigeon, and LeBel Reference Maruna, Russ, LeBel, Maruna and Immarigeon2004:8). A host of other similar terms, such as resettlement, re-entry and rehabilitation, are loosely used to indicate the idea of reintegration, compromising the conceptual rigour of the term (Gisler, Pruin, and Hostettler Reference Gisler, Ineke and Ueli2018). Especially concerning prisoners, the term “reintegration” often assumes that they were already integrated into society before imprisonment, and the prison period is seen as a rupture in their social life. However, this is an erroneous idea, as lack of education, poor employment prospects, drug and alcohol misuse, mental and physical health problems, lack of housing, and lack of familial and financial support often mark the social life of offenders even before their imprisonment (Maguire Reference Maguire2014).

Scholars have also highlighted that reintegration involves a two-way process where the individual prisoner and the community play active roles (Johnson Reference Johnson2002; Maruna Reference Maruna2006). Singh (Reference Singh2016) argues that reintegration aims at facilitating the “ability of the ex-offender to function within the community, within their family, employment and be capable of managing circumstances in a manner that circumvents risk and additional conflicts with the law”. Several scholars have pointed at the centrality and pivotal role of reintegration in the entire prison system, highlighting the argument that the ultimate result of imprisonment can only be assessed based on the successful reintegration of released prisoners in the long term (Burnett Reference Burnett, Burnett and Roberts2004; Galgano Reference Galgano2009; Wilkinson and Rhine Reference Wilkinson and Rhine2005).

Maruna (Reference Maruna2006) suggests that reintegration involves the symbolic element of “moral inclusion”, which includes forgiveness, acceptance, redemption and reconciliation. This is further emphasized by Johnson (Reference Johnson2002:319), who says, “Released prisoners find themselves ‘in’ but not ‘of’ the larger society” and “suffer from a presumption of moral contamination.” Johnson (Reference Johnson2002:328) perhaps offers the most inclusive definition of reintegration and what it ought to be, when he states that reintegration requires “a mutual effort at reconciliation, where offender and society work together to make amends – for hurtful crimes and hurtful punishments – and move forward”. Hence, it becomes clear that the reintegration of released prisoners is a multi-layer concept that includes social, economic, psychological, legal and moral dimensions. Also, scholars have pointed out that the process of reintegration essentially involves two phases: programmes offering support within the institutional setting itself, in advance of the offender’s release, and community-based programmes, often called “aftercare” programmes, to facilitate the social integration of the offenders after their release from the institution (Hải and Dandurand Reference Hải and Yvon2013).

This paper presents an empirical study conducted among 100 released prisoners from India, namely Tamil Nadu (TN) and Kerala, to understand various factors influencing their social reintegration after years of incarceration in prison. The present study identified four outcome variables that capture the socio-economic reintegration and seven contributing variables that influence the released prisoners’ reintegration. Outcome variables brought under the purview of the present study are the following: stability in income, maintaining good relations with the family, maintaining good relations with the community, and membership in informal groups. A reintegration index has been constructed with the help of the responses to these four variables. This index has been used to examine the relationship between reintegration and several supporting factors that influence reintegration. The seven factors (four of them concerning the stay at the prison and three concerning life after release) that influence reintegration identified by the study are the following: visits by family members during the stay at the prison, availing of parole, participation in an employment-related orientation programme at the prison, assistance from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), monetary assistance given to prisoners, the visit by the probation officer, and the years of stay in prison. Though the present study made a comparative analysis of the reintegration of released prisoners from TN and Kerala, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test carried out indicated that there does not exist any significant difference between the respondents of the two States. A correlation matrix was also used to analyse the relationship between the reintegration index and the contributing factors of reintegration. Such an analysis was done to identify the contributing factors that play a significant role in the reintegration of released prisoners. Along with this, qualitative data in the form of interview excerpts also were used to substantiate the results of the descriptive analysis.

REINTEGRATION OF PRISONERS: THE INDIAN SCENARIO

Given the colonial legacy of the Indian context, explicit efforts for bringing in current administrative initiatives in prisons began with the establishment of the Prison Discipline Committee in 1836 under the initiative of Lord Macaulay. While the Indian Prison Act 1894 functions as the basis for prison administration in the country, the same has undergone significant transformations due to various initiatives undertaken during the colonial and post-colonial periods. The first-ever comprehensive study on this subject was launched with the All India Jails Committee (1919–1920). It is indeed a significant landmark in the history of prison reforms in India and is appropriately called the cornerstone of modern prison reforms. In the Indian Jails Committee (1919–1920), for the first time in the history of prisons, reformation and rehabilitation of offenders were identified as the objectives of the prison administration. The Government of India Act 1935, the Model Prison Manual of 1960, the Mulla Committee Report (Mulla et al. Reference Mulla, Khaparde, Sarada Menon, Mallaiah, Rastogi, Prakash, Rasheeduddin Khan and Saksena1983) and the V. R. Krishna Iyer Committee for the improvement of women prisoners (Justice Krishna Iyer Committee 1987) are some of the milestones in the history of India’s prison reform efforts. Especially, the Mulla Committee Report (Mulla et al. Reference Mulla, Khaparde, Sarada Menon, Mallaiah, Rastogi, Prakash, Rasheeduddin Khan and Saksena1983) suggested revolutionary measures to reform and aftercare services to the prisoners; However, sadly, many of such recommendations are yet to be implemented.

Along with a host of measures introduced as part of prison reforms, vocational training was a major aspect of all these initiatives (Hiremath Reference Hiremath2008). In 2005, to revamp the prison administration, emphasizing reform and rehabilitation, the Bureau of Police Research and Development engaged various prison officials, academics and prison experts in drafting a Model National Prison Manual. Some of the critical recommendations of the Manual include the creation of new bodies, including a Department of Prisons and Correctional Services and a full-time National Commission on Prisons; using alternatives to imprisonment; renewing the focus on prisoner rehabilitation; reducing the prison population; and modernizing the prisons themselves (Hiremath Reference Hiremath2008; Ministry of Home Affairs 2016). The Manual was shared with the States and various NGOs working in prisons and prisoners’ rights, but it remains only a policy directive whose actual implementation depends on individual States. Prison reforms are essentially a State subject according to the Indian Constitution; therefore, largely, implementing these recommendations rests with the individual States. Even national agencies – like the National Human Rights Commission or the Bureau of Police Research & Development – cannot ensure the State implementation of policies and schemes listed in the Model Act or Manual (Kumar, Minocha, and Kumar Reference Kumar, Smriti and Narain2010). A host of issues, including the demographic pressure on the prison system, low socio-economic conditions of the offenders, the preponderance of prisoners from disadvantageous communities and the inefficiency of bureaucracy associated with the penal system are contributing to the abysmal scenario of prisoners’ reintegration into India Footnote 1 (Raghavan and Nair Reference Raghavan and Roshni2013).

There have been several studies in the Indian context on prison conditions and reformation practices. However, a serious paucity of studies focusing on the social reintegration of released prisoners using empirical data exists. One of the main reasons for the lack of such studies is the extremely difficult data collection process, as tracing the released prisoners and collecting information from them is a daunting task. One of the few studies that looked at reintegration is the research report prepared by Shrivastava (Reference Shrivastava2011). In the study conducted for the Bureau of Police Research and Development, Shrivastava analyses data collected from 300 samples from the States of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. In addition, in a recent study conducted by Varghese and Raghavan (Reference Varghese and Vijay2020), the authors have highlighted the stigma associated with released prisoners and put forward several suggestions for meaningful rehabilitation of released prisoners.

PRISON REFORM INITIATIVES IN TAMIL NADU AND KERALA

The present study was carried out in two south Indian States, i.e. TN and Kerala. These States have eight types of prisons working directly under the Prisons Department of State Governments. They are Central Jails, District Jails, Sub Jails, Women Jails, Borstal Jails, Open Jails and Special Jails. Prison reform initiatives in these States include measures such as proper food and clothing, medical support, facility to meet family members, education and vocational training programmes, legal aid to prison inmates, the conduct of cultural programmes and sports, counselling extended by NGOs, library facilities, and channelling entertainment by installing television and FM radio. TN has 10.6% of the jails of India, and the corresponding figure is 4.2% in the case of Kerala. TN’s occupancy rate is 62.4%, whereas it is 109.6% for Kerala (National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs 2019). To make the inmates economically independent on their release, the Prisons Department conducts vocational training programmes from time to time. However, the vocational training programmes provided in these prisons vary greatly, as 27.84% of inmates of Kerala had undergone training, whereas it is only 12.12% for TN (National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs 2019). Generally, NGOs take the initiative in supporting the inmates with medical and legal counselling. Such guidance and supporting facilities are reported more by the prisons of TN, which imparted support to as many as 60% of inmates, whereas it is only 15% for Kerala. Both the States have provisions for welfare officers in prisons and an active probation system to monitor and facilitate parole and probation of prisoners.

The present study employed qualitative and quantitative methods to capture various aspects of the social reintegration of released prisoners as the process is complex, multidimensional and requires an interdisciplinary approach. The sample for the study was defined as those released prisoners from TN and Kerala who had served a minimum of six years of imprisonment and had been released between six months and two years before the commencement of the study. This window period was important as it provides sufficient time to evaluate the reintegration experience of the released prisoners. Contacting these released prisoners and collecting data emerged as a significant stumbling block, though the prison authorities provided the residential address of those inmates released during this time. However, there was a considerable discrepancy between the addresses given by the prison authorities and the actual addresses of the released prisoners, as many of them had moved to a new place of residence. In such a scenario, the study focused on released prisoners currently under the probation system, as contacting them through the probation officers was much easier.

The study identified 50 such released prisoners each in the States of Kerala and TN, and most of them were released prematurely and were serving their probation period under the supervision of probation officers. The samples include only males as the number of women who qualify for the definition of samples was minuscule and hard to find and collect data from. For ethical reasons and confidentiality, the respondents were not asked about the details of the crime. The Department of Social Justice in Kerala and the Police Department in TN provided us with the list of released prisoners under the probation period, and they were contacted with the help of probation officers. Footnote 2 Probation officers contacted the released prisoners, and interviews were conducted in mutually convenient places such as houses of released prisoners and public places like parks and restaurants. Fieldwork for the study was carried out between January and December 2019.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RESPONDENTS

The basic information on demographic characteristics of the released prisoners on age, religion, caste, educational qualification, life after release, ownership of the shelter and years of stay in prison was collected during the survey and is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Profile of the Released Prisoners

Source: Primary data.

The majority of the respondents, i.e. 58%, belonged to the 46–60 years age group (25 from TN and 33 from Kerala). The data shows that around 80% of the respondents from both States were 35 years and below when their imprisonment began. As to religion, 81% of them belonged to Hinduism (43 from TN and 38 from Kerala), and this is followed by Christianity (14%) and Islam (5%). For caste, 49% belonged to other backward classes (24 from TN and 25 from Kerala). Footnote 3 This is followed by 32% scheduled castes and scheduled tribes (15 from TN and 17 from Kerala) and 9% general (one from TN and eight from Kerala). Around 20% of the respondents from TN did not disclose their caste identity. On educational qualifications, 12% of the respondents are illiterates, and their numbers are more in TN (10) than Kerala (two). Of the respondents, 18% have completed tenth grade and above, being more among Kerala respondents. For living arrangements, 87% stay along with their family members (44 from TN and 43 from Kerala), whereas the remainder live alone. As for ownership of shelter, 58% stated that they own a house (25 from TN and 33 from Kerala). This is followed by people who stay in rented houses (31%) and temporary shelters (11%). Of the respondents, 9% stayed in jail for more than 20 years (seven from TN and two from Kerala), 36% for 16–20 years, followed by 33% for 11–15 years and 22% for 6–10 years.

A cursory analysis of the demographic and socio-economic conditions of the sample reaffirms the need to establish robust mechanisms for the reintegration of released prisoners. The majority of them come from underprivileged sections of society, and a vast majority of them are imprisoned at a relatively young age. Predictably, with very low educational and economic backgrounds, they find their life after release from imprisonment especially hard. These factors reaffirm the relevance and necessity for standardized procedures and mechanisms to reintegrate prisoners upon their release.

FACTORS AFFECTING SOCIAL REINTEGRATION

Successful reintegration of inmates released from prisons after prolonged incarceration results from a host of factors and processes. While several prison reform initiatives have been formulated to facilitate reintegration, a host of social, economic, cultural and familial factors play a central role in this process. While numerous factors can be identified as exerting direct or indirect influence on the social reintegration of released prisoners, this paper identifies and analyses seven important factors in deciding the nature of social reintegration. The present study presumed that six factors, namely, training programmes attended at the prison, visits by family members during the prison sentence, availing of parole, help from NGOs, financial support received at the time of release, and the role of probation officers do have a positive impact on reintegration. In contrast, the years of imprisonment have a negative implication on reintegration.

The Training Programme at the Prison

While prisons in India are yet to institutionalize various mechanisms aimed explicitly at reintegrating prisoners, many prison reform measures are expected towards this objective. The welfare officers must implement a series of welfare measures for prisoners’ educational, psychological and social well-being to equip them better for the outside world upon release. Besides these initiatives by the jail authorities, several civil society organizations – mainly affiliated with different religious institutions and organizations – have taken up activities like spiritual classes, religious education, teaching yoga, vocation training and more. All these initiatives are expected to facilitate their reintegration with society once they are released. One of the most important measures adopted by the prisons in Kerala and TN is encouraging the inmates to undergo specific vocational training programmes. These programmes are intended to enable them to acquire skills that could be used to undertake income-generating activities after their release and motivate them.

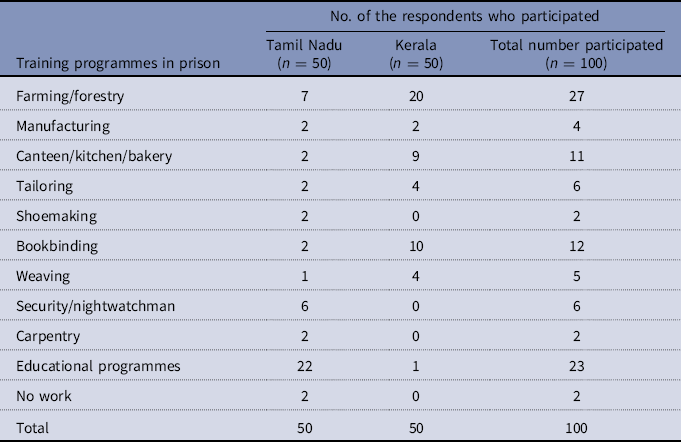

Most of the released prisoners underwent different training programmes during their stay in prison. Table 2 elaborates on the distribution of prisoners of TN and Kerala by the vocational training and jobs they had undertaken during their incarceration. Those who spent more years in prison had participated in more than one trade.

Table 2. Training Programmes Attended at the Prison by Respondents

Source: Primary data.

Except for two from TN, 98% of released prisoners participated in other vocational training or skill enhancement programmes. Of the prisoners, 23% had taken part in educational programmes organized by prisons, and the participation in such programmes was 22 in TN, whereas it was one for Kerala. For farming or forestry, 27% had taken part in (seven from TN and 20 from Kerala). TN prisons department promoted the education of prisoners, and this helped certain illiterates become literates. Farming was considered the best alternative for those who were not ready to learn any new skill, especially when they had compulsions to undertake some activities. Kitchen/bakery/canteen (nine) and bookbinding (10) were the important trades learned by ex-prisoners of Kerala. Security/night watchman was a job undertaken by six from TN, and it was more of a job given to reliable prisoners rather than a skilled activity that requires training. Manufacturing (4%), shoemaking (2%), tailoring (6%), bookbinding (12%), canteen/kitchen/bakery (11%), weaving (5%) and carpentry (2%) were the major trades where 37% of the released prisoners participated and such participation giving some training in new skills was well below 40%.

The wage received by the convicts as remuneration for their labour during their stay in prison is a vital financial resource for meeting their expenditures during the prison stay and those of their families. Several prisoners either sent money regularly home or systematically saved it as an important resource when released. The daily wage of prisoners in Kerala in 2019 ranged from 0.87 U.S. dollars (USD) for an apprentice to 3.17 USD for a skilled worker. TN revised the rates from 2017, and they ranged from 2 USD to 2.75 USD. Before that, 0.8 USD, 1 USD and 1.2 USD were paid in TN for unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled workers. In Kerala, the corresponding figures were 0.70 USD for an apprentice, 1.4 USD for skilled and 1.6 USD for additional duties before December 2017. The real wage was minimal for the study respondents who spent several years in prison before this revision.

Moreover, in TN, 50% of the wage was retained by the prison authorities for prison upkeep, 20% was withheld for victim compensation, and only 30% was given to the prisoners as their real wage. This left very little money with the prisoners at the time of their release, and this was evident in our study as well, as a vast majority of the released prisoners stated that they had a meagre amount with them at the time of release. In a significant judgement given in February 2019, the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court in TN ruled that 50% deduction by the jail authorities is unconstitutional, providing much-needed relief to the prisoners. In general, prisoners from Kerala had much better savings – ranging from 150 USD to 900 USD – upon their release, and it helped them settle down with their new lives more easily. Most prisoners regularly sent their savings to family members or carried them with them during parole visits.

Visits by Family Members

Another critical variable important in the process of reintegration of prisoners is the quality of relationships with immediate family, and, in this study, the same was measured by analysing the frequency of the visits to the prison by family members and close relatives. Based on the data collected, 90% of the respondents (47 from TN and 43 from Kerala) were visited by their family members. These visits played a major role in providing them emotional reassurance and also helped them to rebuild relationships. The ex-convicts vouched that these visits gave them the strength to survive the ordeal in prison and instilled hope for the future. During the visits by family members, significant discussion themes included welfare and education of the children, management of monthly family expenses, the general well-being of the family, meeting with the probation officer and availing parole. In a few instances, the prisoners were upset that those they needed the most refused to meet them at the prison. The frequency of these visits gradually reduced as prisoners could avail parole and began visiting their families more frequently. A few other prisoners also reported that they asked their family members not to come to the prison, considering that it might not be safe for women.

Availing Parole

The system of “paroles” (furloughs) where the prisoners are released for a fixed duration to spend time with their families plays a significant role in safeguarding the psycho-social well-being of the prisoners and is extremely important in making their social reintegration a smooth affair. These periods of leave, ranging from a week to one month, act as periods of relief for the prisoners and provide them an opportunity to get back to their family and immediate social circles. It is also important to note that the probability of availing of paroles for a prisoner is the function of healthy family and social ties, as these factors are taken into consideration by the probation officer and jail authorities in deciding whether a prisoner can be granted paroles. In this process, the role of the probation officer is crucial as his report is vital in deciding whether to grant parole or not to a given prisoner. The primary data collected from the respondents indicate that 91% (43 from TN and 48 from Kerala) had availed paroles during their stay, leaving only nine inmates who did not avail the same during their entire stay. A vast majority of the respondents who availed of parole pointed out that they utilized the parole period for spending quality time with their family members and immediate relatives. The following response from a released prisoner from Kerala summarizes the typical response about parole, especially those who maintained healthy relationships with family members:

I have availed parole (furlough) several times, and during that time, I was able to reconnect with my family and my neighbours. I used to take my wife and son out for shopping and movies. I also talked to the people around; they were all very welcoming and well-behaved. They always supported me and did not show any type of hatred towards me. I focused on spending more time with my family than doing anything else. Sometimes I feel sad when I have to go back to prison after my parole. I feel depressed for a while but will turn fine in a week or two.

Many inmates used parole, especially if they could avail themselves of longer periods of a month’s leave, to engage in some informal work to earn money during their stay at home. On the other hand, some respondents (seven from TN and two from Kerala) either did not avail paroles. Most of such people either had strained family relationships or lacked family support in seeking parole. Especially for those who committed murders of immediate family members, parole was not a very welcoming idea.

Financial Assistance

Given the economic backwardness of most prisoners and the precarity at the time of release, the availability of financial support is an important factor in deciding the nature of the social integration of released prisoners. Among the respondents, 64 persons (24 from TN and 42 from Kerala) stated that they received funds when released from prison. The Social Justice Department of the Kerala Government currently provides around 210 USD to every released prisoner, and most prisoners opined that while this money is a big relief, it is hardly sufficient. In TN, the Discharged Prisoners Aid Society, an institution set up during the British times to provide financial aid to released prisoners, is expected to provide 350 USD. However, the functioning of these societies has been seriously affected by legal battles and bureaucratic bottlenecks. Especially, the Discharged Prisoners Aid Society in Chennai, TN, which owns a very expansive commercial building in the heart of Chennai city, has been virtually defunct for several years, thereby denying the released prisoners their rightful help. In Vellore, TN, the society seems to be working well, and several released prisoners have availed of its financial help.

Help From Non-Governmental Organizations

While many civil society organizations work within prisons, providing moral and religious classes, conducting programmes, providing yoga classes, and more, only a couple work to rehabilitate or reintegrate released prisoners. In Kerala and TN, the Prison Ministry of India (PMI), a Catholic organization run by priests, works with several released prisoners in a highly focused and systematic way. In TN, 12 respondents informed that the PMI gave help during their release from prison. Along with providing financial support, the PMI provides spiritual support to the needy prisoners and, in many instances, takes care of their families while they languish in prison. Many of these people who received financial assistance from the organization used it to buy small assets like goats and cows or start a small eatery.

Role of Probation Officers

Probation officers are expected to play a key role in the supervision of prematurely released prisoners for a stipulated time of three to four years. They are expected to facilitate the rehabilitation as well as reintegration of the released prisoners. The combination of supervisory, facilitatory roles and surveillance make probation officers extremely important players in the social reintegration of released prisoners. They are expected to be in close contact with the released prisoners and constantly supervise their life, ensuring that they do not get back to unlawful activities and recidivism. Probation officers are expected to frequently visit, monitor and provide guidance to the released prisoners to help them integrate with society. Of the respondents, 21 stated they were visited frequently – at least once per month, consisting of 19 from TN and 2 from Kerala. The remaining 79 stated that they were visited occasionally – once in three to six months. Instances of irregular visits were comparatively high in Kerala.

Duration of Stay in Prison

The longevity of incarceration has a direct bearing on the process of released inmates as prolonged imprisonment significantly hampers their ability to adapt to the external environment and lead a normal life. The data collected from the field shows that 36% of the respondents spent 16–20 years in prison, followed by 33% spending 11–15 years, 22% spending 6–10 years in jail, and 9% spending more than 20 years in jail. Especially those who hail from the socially disadvantageous sections, crippled with low economic status and educational levels, long years of imprisonment virtually hamper their prospects for gainful employment and meaningful participation in society. Several respondents mentioned that they felt clueless about the changing technologies and were incapacitated due to their lack of familiarity. The common refrain is that “the world has changed so rapidly that we found ourselves in a completely different place upon release”.

SOCIAL REINTEGRATION THROUGH ECONOMIC STABILITY, RELATIONSHIPS WITH FAMILY AND COMMUNITY, AND INVOLVEMENT IN INFORMAL GROUPS

For this study, we identified four important factors as reflective of the social reintegration of released prisoners, and the assumption is that fulfillment of these factors reflects high social reintegration. These factors are economic independence or stability of income, good relationship with family, good relationship with the community, and membership in informal groups. The following section analyses each of these factors.

Our data indicates that 80 respondents (45 from TN and 35 from Kerala) are involved in some employment activities after their release from prison to support their families. Almost 20 respondents revealed that they are not employed, mainly due to their poor health due to age and illness. While 44 respondents (16 from TN and 28 from Kerala) stated that they are the major breadwinners of their family, 29 (18 from TN and 11 from Kerala) stated that they have a stable income. It is important that released prisoners’ economic stability is weighed against the vocational training programmes that the respondents had undergone in prison. The data shows that training-cum-work that the respondents undertook in prison had not enabled them to continue with similar activities after release. Validating this assumption, a whopping 98% of the respondents (48 from TN and 50 from Kerala) stated that training received in prison did not help them find a job after release. There are several reasons for this situation. Many of them felt that their aspirations and motivations were never taken into consideration while assigning them a specific job during imprisonment, and, as a result, they did not develop any interest in them. The major problems were the lack of adequate financial capital to start a trade for which they were trained and the outdated training that made it impractical to undertake in normal life. Many of the respondents wanted to start a business of their interest rather than pursuing the trade they had learned in prison. Several respondents pointed out that they went back to their earlier job like daily wage workers, driving and so on as the trades they learned inside prison were not suitable outside. For example, bookbinding or shoemaking did not have adequate demand in the market. One of the respondents from TN pointed out that jobs like shoemaking carried a stigma in society, and people from other castes could not take up these trades easily.

One of the most significant markers of the social reintegration of released prisoners is their active involvement in familial and social activities. Their ability to mingle with the family, community, and life as a functional member is of utmost importance. The respondents were asked about their sense of acceptance within the family and wider society. They were also asked whether they were invited for family functions, community affairs, and involvement in organizations and religious gatherings.

Our data shows that respondents experienced seclusion from society after release, and, at times, circumstances forced some of them to change their place of residence on account of harassment and insults from the community they lived in earlier. Twenty-nine respondents (14 from TN and 15 from Kerala) changed their place of residence involuntarily. Twenty-five respondents (13 from TN and 12 from Kerala) found it difficult to socialize after their release. Eighteen respondents (10 from TN and eight from Kerala) experienced emotional trauma. Seven respondents (three from TN and four from Kerala) experienced harassment or insult from society. Eight respondents (four each from TN and Kerala) found it difficult to find a residence after their release. Three respondents (two from TN and one from Kerala) stated that they had been denied welfare services such as an old-age pension, social security schemes and more. Ninety respondents (45 each from TN and Kerala) stated that they maintain a good relationship with family and friends. Forty respondents (28 from TN and 12 from Kerala) are involved in the activities of religious groups. Only 15 respondents (three from TN and 12 from Kerala) have membership in informal groups. Seventy-three respondents (42 from TN and 31 from Kerala) stated that they were accepted and welcomed by their family members and community during special occasions and ceremonies.

The nature of the crime, family situation and affiliation with social groups play an important role in deciding the respondents’ integration into society. Released prisoners who were sentenced for political murders continue to be active members of the party even after their release, and this is especially true in the case of Kerala. On the other hand, people who got involved in crimes as a part of criminal gangs were highly apprehensive of the influence of friends and would like to lead a more isolated life. “No more friends, I got into problems only because of them, now I lead a very reclusive life, focusing only on our matters” seems to be a common refrain. Most of them found it very hard to socialize immediately after the release but later found it easier. Many respondents informed that people in the locality have come to terms with the crime and have reconciled with them, leading to their gradual acceptance. Many expressed the confidence that their innocence is known widely by the public, and hence they are easily accepted back after their release.

An important observation in qualitative data is the close connection between economic independence and acceptance within family and society. Those who could come out of prison with some reasonable savings and find a job received more acceptance within their family and outside. Similarly, those who had property in their names found better acceptance by the family. Many elderly respondents who were unable to find a job or were incapable of pursuing one felt that they had become a burden on their family and found no reason to believe that they were important community members. Most of these respondents wished for a regular income or economic independence and felt the government must do more for them. Many of them complained that a self-reliant life is impossible as they do not have enough capital to start their ventures like buying an auto-rickshaw or starting a small eatery. The technical difficulties in getting a loan from a bank or other private enterprises due to their history of imprisonment and lack of proper documents are major hurdles. Statements such as “I avoid functions and events because without money they do not give respect to me. They usually talk behind my back” reflect these difficulties.

ASSESSING SOCIAL REINTEGRATION – REINTEGRATION INDEX

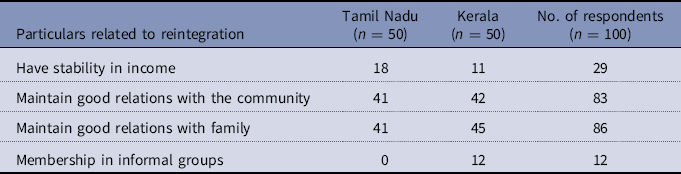

To present the nature of the reintegration of released prisoners in a more cryptic manner, we developed a table (Table 3) that shows the distribution of the samples across four outcome variables of reintegration.

Table 3. Outcome Variables on Reintegration

Source: Primary data.

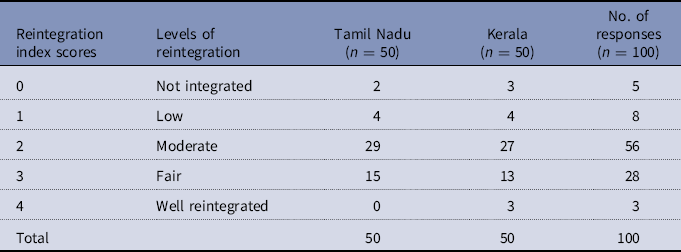

Based on the distribution of outcome variables, a reintegration index was constructed to capture the combined effect of the outcome variables and is presented in Table 4. It is constructed by giving equal weighting to all four outcome variables. The value of the reintegration index varies from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates no reintegration of the released prisoner and 4 indicates a complete reintegration of the person with the society.

Table 4. Reintegration Index

Source: Primary data.

Based on the reintegration index constructed, we grouped the released prisoners into four levels: not integrated, low, moderate, fair, and well reintegrated. Only three respondents were completely reintegrated (none from TN and three from Kerala). On the other hand, five respondents were not reintegrated with society (two from TN and three from Kerala). Of the ex-prisoners, 56% of were moderately integrated (29 from TN and 27 from Kerala), and 28% of the respondents were fairly integrated (15 from TN and 13 from Kerala). There are no significant differences in the reintegration of respondents from TN and Kerala. Poor membership in informal groups and lack of stability in income expressed by the respondents contributed to most respondents being under moderate to fair reintegration, though they maintained good relations with community and family.

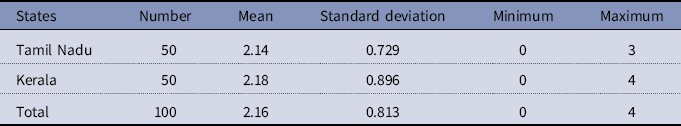

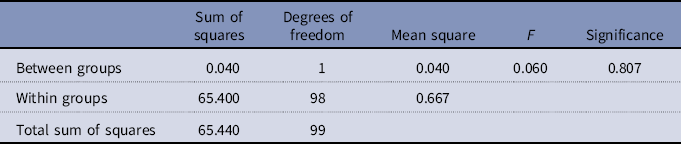

Descriptive statistics on the reintegration index and the results of the ANOVA test are presented in Tables 5 and 6. The ANOVA test was carried out to examine whether there are significant differences in the reintegration indices of TN and Kerala.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics of Reintegration Index

Source: Primary data.

Table 6. Analysis of Variance Table

Source: Primary data.

Mean integration indices show that Kerala respondents are more reintegrated than in TN but with a higher standard deviation. Kerala’s maximum reintegration score is 4, whereas it is only 3 for TN.

The F value of the ANOVA table indicates that there is no significant difference in the reintegration of released prisoners across States. Since the ANOVA test result does not show any significant variation in the reintegration of released prisoners, a grouping of respondents by the State for further analysis appeared insignificant.

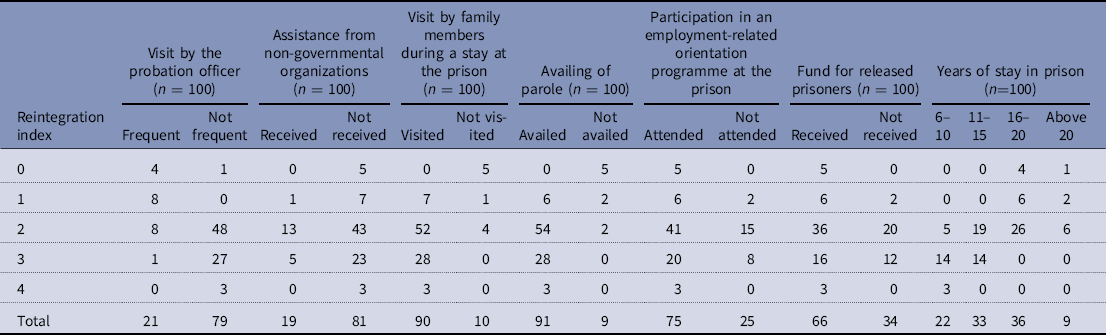

Table 7 shows the cross-tabulation between the seven contributing factors and reintegration index. The study hypothesized that all the six variables positively contribute to reintegration, except the years in prison. On the other hand, the years of stay are expected to have a negative relationship with reintegration.

Table 7. Relationship Between Contributing Variables and Reintegration Index

Source: Primary data.

Table 7 indicates that the majority of the respondents had received assistance from NGOs (81), been visited by family members during their stay in prison (90), availed parole (91), participated in training programmes (75) and received funds for released prisoners (66). Among those who had not reintegrated (reintegration index=0), factors such as participation in employment generation programmes at prison and funds received for released prisoners had not contributed towards reintegration. This was supported by the interview statements that the respondents found it difficult to undertake income-generating activity based on the skills they learned in prison. Thus, economic integration becomes an unrealized goal for most of them, even though they were trained in various skills in prison. Similarly, visits by family members during the stay in prison, availing parole and shorter years of stay in jail contributed positively towards a higher reintegration index (reintegration index=4), as could be seen from the responses of those reintegrated completely.

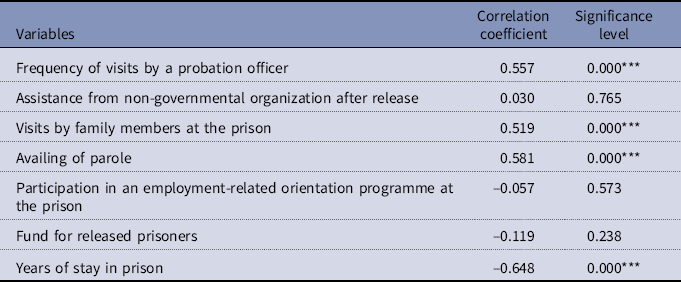

A correlation matrix has been constructed to examine the relationship between these seven contributing factors and the reintegration index and is presented in Table 8.

Table 8. Correlation Matrix of Reintegration Index and Seven Contributing Factors

Source: Primary data.

*** p<0.001.

Availing parole during the stay in prison and having visiting family members at the prison are highly correlated with the reintegration index, and it is significant at the 1% level. A close contact established with the family through parole and visits of the family members enable the ex-prisoners to reintegrate quickly after their release. Another significant variable (at 1%) is the probation officers’ frequent visits after release. Close supervision and monitoring by a probation officer are likely to create confidence in the mind of the released to be careful in his deeds and inculcate the necessity of reintegrating with society. Another significant variable correlated with the index is years of stay in prison, and the result indicates that it is negatively correlated at a 1% significance level. Thus, more years of stay in prison bring down their connection with family and community, thereby negatively affecting reintegration after their release.

An examination of participation in vocational training programmes at the prison, fund for released prisoners, and NGO/civil society organizations’ assistance for released prisoners indicates an insignificant correlation with the reintegration index. Since the above four factors could contribute significantly to the economic integration of the released prisoners and their easy reintegration with society, it is expected to play a positive role in the reintegration process. However, according to the responses given by the prisoners, the vast majority of them found that the vocational training received during their stay in prison had no significant role for their livelihood initiatives outside prison due to a host of reasons, as elaborated earlier in the present article. Similarly, as mentioned earlier, the role of civil society organizations and the fund received at the time of release also appear inconsequential in social reintegration.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Analysis of our data shows that the extent of social reintegration of released prisoners in this study provides a somewhat favourable picture, as the vast majority show moderate to fair degrees of reintegration. However, it needs to be reiterated that this relatively favourable picture results from the very nature of samples selected for the study: the respondents were released after their imprisonment – mostly prematurely – and currently under the probation system of supervision. By default, these released prisoners are bound to be endowed with better social and familial support as these factors are considered by prison officials and probation officers while providing timely parole and their release.

At the same time, the study results also point towards a host of limitations associated with the prison reformation processes in place. One of the significant findings of this study is the disconnect between the vocational training programmes offered in prison and their futility in providing livelihoods after prisoners’ release. The vast majority of the respondents are emphatic about this disconnect. Scholars have also pointed out that the idea of vocational training in India indeed plays a minimal role in the rehabilitation of released prisoners as they are mostly aimed at keeping the prisoners occupied (Vineetha and Raghavan Reference Vineetha and Vijay2018). This is also an indication of the ineffectiveness of prison mechanisms to facilitate rehabilitation upon release, including the very limited role of welfare officers. Released prisoners did not see any significant role of welfare officers in making their re-entry more efficient and smooth. In their responses, only 12 released prisoners (three from TN and nine from Kerala) stated that they received any meaningful support from the welfare officer for their rehabilitation and reintegration. Especially given the uncertainty associated with premature release and the lack of a support system, prison officials, especially the welfare officers who are already overburdened with workload, are not in a position to offer any meaningful advice or handholding to these people. A vast majority of the respondents informed that they were given friendly advice/warning to “never come back here” by the jail officials and welfare officials.

Despite the ineffective measures within prison, many respondents demonstrated a reasonably good degree of social reintegration, mainly because of their favourable familial and community relationships. The released prisoners repeatedly affirmed the importance of periodic paroles as a pivotal factor in their reintegration as they provided them much-needed opportunities to reunite with their families and the larger community. As mentioned above, the nature of the crime, relationship with the victims, degree of social stigma, economic resources and so on play a vital role in this process. In particular, the lack of economic resources to initiate a new livelihood upon release continues to be the most significant challenge for most released prisoners, especially those from poor backgrounds. The assistance given by the government (in the case of Kerala) and other agencies like the Discharged Prisoners Welfare Society (in the case of TN) and NGOs was insufficient to address this challenge.

It is disheartening to note that even after several decades of prison reforms and numerous committee reports to implement a systematic and coordinated protocol for effective rehabilitation and reintegration of released prisoners, this critical component of the modern penal system remains rather neglected. A pertinent vision was given by the Justice Mulla Committee that “a prison system which shall not be just another link in a chain of persecution of an offender but will attempt at reforming and reconstructing him into a self-respecting, self-reliant individual through a purposeful approach of training and treatment” remains unfulfilled (Mulla et al. Reference Mulla, Khaparde, Sarada Menon, Mallaiah, Rastogi, Prakash, Rasheeduddin Khan and Saksena1983:262). The Committee listed out 16 concrete proposals for strengthening the reformative and rehabilitative focus of the Indian prison system. Sadly, many of these recommendations have not been implemented in India, and the States of Kerala and TN are not exceptions when implementing the Mulla Committee’s recommendations.

While the situation in these prisons has improved tremendously over the past several decades and the outlook of prison officials has changed significantly, a lot more concerted efforts with specific policies and programmes with a heavy focus on prison as a space of correction must be implemented. As a primary step in this direction, a systematic classification of prisoners must be introduced in every prison. These classifications must be based on the following parameters: nature of the crime, whether repeat offence, first-time offence, severity and premeditated, and so on; socio-economic and familial background, education and possession of skills; emotional and psychological characteristics. This classification must be used as a benchmark to devise a focused reformation plan during their stay in prison. At the same time, this classification must not be based only on certain psychometric tests that classify the inmates mechanically into certain groups. This classification will also help to devise better reformation practices for offenders of the new-age crimes such as the ones that come under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (2012), the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005), Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (2019) and cybercrimes that require more sophisticated intervention plans in prisons so that the offenders are given specialized counselling and awareness along with psycho-social interventions with the goal that a definite attitudinal change takes place among them.

In order to plan and execute a classification-based regime in prison and evolve a more sensitive and effective reformative mechanism, the correctional branch of prison must be strengthened with additional personnel and resources. The correctional aspect of prison must be seen as a pivotal domain that requires the service of qualified professionals. While more social workers and counsellors are required as professionals, existing operational staff who take care of retention/custody must be given sufficient training and awareness in these matters so that their support also can be harnessed.

It becomes evident from the study’s findings that skill enhancement programmes and vocational programmes introduced in prison must be sensitive to the changes taking place outside in society. Archaic and outdated skills might be useful in keeping the prisoners busy during their tenure but do not contribute much to their rehabilitation and social reintegration. Similarly, given the centrality in facilitating social reintegration, the parole system must be regularized and procedures standardized. Similarly, the Probation Office must be strengthened, and the probation officers must act as liaison officers between the wider society and the institution of prison. Their role must be seen as a professional one that requires specialized skills, knowledge base, and methodological rigour, and, hence, people with professional qualifications in disciplines like criminology, social work, and so on must be considered for this post. Probation officers must work with the local community to explore rehabilitating the released prisoner who requires such assistance. Community participation has been proven effective in many places for ensuring the effective social reintegration of released prisoners. It becomes evident through the study that the rehabilitation and reintegration of released prisoners depend on complete and structural changes in the prison system and the overall philosophy that informs the ultimate aim of imprisonment. While the prison system has seen a substantial transformation over the last several decades in prison reforms, more concerted efforts must be adopted for the needy prisoners who require help in their reintegration process.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Human Rights Commission, Government of India, New Delhi, for funding this research.

R. Santhosh has a PhD in Sociology and is an Associate Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India. He specializes in the Sociology of Religion and has published articles in journals such as Modern Asian Studies, Ethnicities, European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, and Journal of Historical Sociology.

Emil Mathew has a PhD in Economics and is currently working as Assistant Professor in the School of Maritime Management, Indian Maritime University, Chennai, India. She specializes in areas of sustainable development and maritime economics.