In 2014 the Israeli parliament passed a law setting 30 November as the “Day of Remembrance for the Departure and Expulsion of Jews from the Arab Countries and Iran.”Footnote 1 The date was chosen for its symbolism, as it directly follows November 29, the day on which, in 1947, the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was adopted, leading to the establishment of Israel. In Israel the day is marked annually with ceremonies, academic conferences, and exhibitions.Footnote 2 This legislation's attempt to lump many different stories together into a single simple-to-digest narrative was flawed from the outset. A fundamental flaw with this construction is the notion of collective expulsion of Jews from all Middle East and North Africa (MENA) states, including Iran. In this article I argue that the inclusion of Iran in the memorial law and the grand “expulsion” narrative stems from a profoundly erroneous analysis of the modern history of Jews in Iran and politically rooted motivations to create a unified narrative of Jewish exodus from Middle Eastern countries.

At the same time the law and narrative mean to erase the Iranian Jewish presence in Iran and deny historical agency to that community, to dismantle the anomaly that is the mere existence of a Jewish community in Iran in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and to reaffirm the long-held belief that there cannot be a Jewish presence in Iran in the age of the Islamic Republic. To be sure, I do not deny the existence of anti-Semitism in Iran or the attendant hardships that Iranian Jews continue to experience in their navigation of a terribly stymied and complicated situation. My intent is to situate them outside of the binary of either lying about their true aspirations to satisfy the ever-suspicious regime, or hiding or fleeing the country when they have the opportunity.

Such a corrective seeks to amend the way in which we read and write the contemporary history of the Jews of Iran, and to let readers see the many possibilities for Jewish existence in postrevolutionary Iran. By tracing the radical transformation of the Iranian Jews in the second half of the 20th century, until the revolution, I hope to contextualize the once-close historical and political ties between Iran and Israel. Only in this manner can one properly understand the participation of Jews in the revolution, their adjustment to life in the Islamic Republic, and their participation in the postrevolutionary nation-building project. By resituating the 20th-century experience of the Iranian Jewish community in this way, the conventional wisdom surrounding the presidencies of Mahmud Ahmadinejad (2005–13) and Hassan Rouhani (2013–21) is dramatically altered.

The narrative that connects the exodus of MENA Jews to the establishment of Israel aims to create a correlation between the mass departure of Jews due to the supposed inherent anti-Semitism of Middle Eastern societies and the inevitable solution: emigration to Israel. This is the reason that the Israeli legislature chose the 30 November date. This date—in 1947—marks, according to most historiographical traditions, the beginning of the 1948 Palestine war (also known as Israel's War of Independence, and the Nakba). Selecting this date suggests that any Jewish outflow from any Middle Eastern country, whether it occurred in 1948, 1956, or 1967, is as if it happened in 1948, explicitly because of the creation of Israel and the (again, supposed) immemorial Muslim–Jewish rivalry.

However, when we examine Jewish emigration from the Middle East and North Africa, we see a profoundly different pattern, one that is better connected to colonialism and the decolonization of the 1950s and 1960s. In the past decade, scholars have examined the legal structures that distinguished religious minorities from Muslims in Muslim-majority countries and cultivated their hybrid or empire-oriented identities. The legal and social structures granted privileges to Jews and Christians who performed their Western identity and rewarded them with capitulatory rights, representation, upward mobility, and more. In some cases, the ultimate reward was imperial citizenship (Algeria following the Cremieux Decree), and in others the social and economic benefits of easier access to imperial resources (bureaucracy, economy, education) in the MENA country, or in the metropole.Footnote 3

These colonial and imperial identities (that led to opportunities) were supplemented by cultural projects, such as European-style education in the French-medium Alliance Israelite Universelle schools and missionary and private schools that bestowed upon them a lingua franca, different than the majority society's language. This education and professional training opened doors for them to travel to the metropole for additional education and opportunities. Jewish experiences in the 19th and 20th centuries were inadvertently tied to the colonial condition.

Arguably 1948 signaled the beginning of mass emigration from most of the Arab countries (in a process that lasted almost two decades). Nevertheless, it is not the only explanation for the departure of the majority of Jews. Iraq is perhaps the clearest example of an exodus directly resulting from the establishment of Israel.Footnote 4 Morocco, which had the biggest Jewish population in the MENA region in 1948, with some 250,000 Jews, saw about 90,000 leave between 1948 and 1956.Footnote 5 In the decade following Moroccan independence and decolonization the number of Jews remaining in the country dwindled rapidly. By 1967, 53,000 remained in Morocco, and that number shrunk steadily; in 2022 only 3000 lived in Morocco.Footnote 6 Similarly, the Jews of Tunisia left after independence in 1956, most of the Jews of Algeria emigrated in 1961 and 1962, and Jews left Libya in 1951.Footnote 7 In Egypt, the majority of the community left in 1956 following a period in which there was a revolution (which was quintessentially anticolonial); a war against Israel, France, and Britain; rising xenophobia; and the implementation of “Egyptianization” laws that targeted noncitizens, a category that included many Jews, but also members of the other foreign communities, predominantly Greeks and Italians.Footnote 8 Lebanon saw its Jewish community leave with the eruption of the Lebanese Civil War in 1958, domestic political strife not directly connected to the establishment of Israel.Footnote 9

To the contrary, during these two decades in which the MENA countries lost most of their Jewish populations, Iran witnessed an incredible period of rapid integration of Jews (and other minorities) into Iranian society. During the 1950s and 1960s Jews increasingly became part of the nation-building project of the Mohammad Reza Pahlavi era (r. 1941–79).Footnote 10 This is not to say that between 1948 and the 1979 Iranian revolution the community did not experience drastic changes in its size and experience, but it helps to explain the anomaly of the Iranian Jewish experience in the Middle Eastern context. I argue that the absence of a dominant colonial power in Iran, or the existence of a merely semicolonial structure, annulled the establishment of the configuration of Jewish dependency on European powers or, at the least, avoided the typical strong identification of Jews with foreign powers, one that was normal in societies that were under direct colonial or imperial rule. Although Zionism a had significant presence among Iranian Jews as a cultural and to various degrees a political movement, Iranian Jews overwhelmingly identified with the Iranian national project, one which they claimed as their own.Footnote 11

The Anomaly of the Kalimian

This anomaly has produced serious misunderstanding of the history and conditions of Jews in Iran, especially in the second half of the 20th century and continuing into the 21st century. There are three main names for Jews in Persian: Yahudi, which is considered neutral; Juhud, which is derogatory and insulting; and Kalimi, which is the most respectful and comes from the Qur'anic epithet of Moses, Kalim-Allah, the one who spoke with Allah. The Kalimian are therefore the followers of Moses.Footnote 12 As of 2022, among Middle Eastern nations the Jewish population of Iran remained second only to Israel. Still, with around 15,000 to 20,000 Jews remaining in the country, it is only a shadow of its former self.Footnote 13 In the decades between the 1940s and the 1960s, Iran saw its Jewish population rise to 100,000 individuals as a result of regional migration from Iraq and even return migration from Israel.Footnote 14 It was in the aftermath of the 1979 revolution and the four decades since that the Jewish population shrunk to just a fraction of its prerevolutionary size. Despite this, Jewish history has not ended in Iran. Ever since 1979, Iranian Jews have battled attempts to erase their voices and narratives in Iran by the imposition of a conflated identity (Jewish/Zionist) and the growing “need” to be Muslim to be Iranian.

The attempted narrative erasure by the Israeli state is part of a much wider phenomenon. Over four decades of conflict between Iran and the West, particularly regarding Zionism, have distorted the Israeli public's ability to understand Iranian society. Additionally, the nature of Iranian historiography, which tends to focus on the Shi'i Persian majority and write history through their experiences, disregards the many religious and ethnic minorities who participate in Iranian society.

At present Israel and Iran remain trenchant enemies, embroiled in an ongoing cycle of recrimination involving vows of destruction, proxy wars, and accusations of human rights violations. Israeli public perception is that anti-Semitism within the Islamic republican context is more radical and dangerous, since, allegedly, it is rooted historically in Islam. The broader context of Iran's relations with the West after the 1979 revolution—the American hostage crisis, President George W. Bush's “axis of evil” address, the subsequent invasion of Iraq, the nuclear negotiations, President Ahmadinejad's repeated denial of the Holocaust, the confrontational anti-Western rhetoric of the Islamic Republic's regime, Israeli threats of and reputed military strikes and targeted assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, and the rhetoric of “regime change”—has impeded open public discussion and dispassionate academic work on Iran, particularly with regard to the affairs and status of minorities.Footnote 15

Ever since the Islamic Revolution, scholars and commentators have viewed Iranian Jews as existing in a state of taqiya (dissimulation), the Shi‘i practice that allows the believer to hide one's true faith to protect oneself from persecution.Footnote 16 Anything Iranian Jews might say pertaining to living in the Islamic Republic is assumed to have been articulated from this cloaked position and so would never truly express their heartfelt thoughts or deeds.Footnote 17

Another concept that is taken from the Shi‘i religious vocabulary that appears frequently in writings about the “nature” of the relationship between Shi‘a and Jews is najes (impure), for example, the belief that by a single touch a non-Muslim (or even Sunni in a Shi'a society) can make food or even a whole street impure. This condition dictates another set of limitations and additional burdens for Jews living in Muslim lands. In her inaugural speech (April 21, 2021), the newly elected member of the Knesset from the Likud Party, Galit Distal Atbaryan, talked about her childhood memories of her Iranian-born parents telling her about their trauma of being treated as najes in the bazaar in Isfahan. Atbaryan's parents left Iran at the beginning of the most profound development and upward mobility trajectory that Jews have experienced in Iran, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and after. Even then cultural and religious norms were not applied, practiced, or enforced equally across the country.Footnote 18

Concepts such as taqiya, dhimmi, and najes have special designation in the line connecting scholarship, public discourse, and policymaking. As Daniel Schroeter aptly asserted: “Although dhimmi denotes a legal status that applies to non-Muslim ‘people of the book’ generally, especially Christians, who were much more numerous in the Islamic world than Jews, scholars and activists who write on anti-Semitism without expertise on Islam and the Middle East use the term as an alarm bell regarding the dangers of Islam to the Jews.”Footnote 19

In the context of Iranian Jews, the seminal work that served the scholarly community and the general public was Habib Levy's Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran: The Outset of the Diaspora (in Persian, Tarikh-i Yahud-i Iran).Footnote 20 Levy's own biography is important in the context of this book. He was one of the leaders of the Iranian Jewish community: a prominent philanthropist, industrialist, and Zionist organizer and activist. Levy was never trained as a historian, and his engagement with writing Jewish history started in his youth when he read Heinrich Graetz's The History of the Jews.Footnote 21 Although Levy's work carries some important documentation, community narratives, and oral history, it lacks any historical methodology or theory, which proves to be highly problematic when trying to present a narrative of 2700 years.Footnote 22 Originally written in Persian and published in three volumes between 1957 and 1961, it recounted the history of Iranian Jews from the Babylonian exile until 1961 (the English-language edition extends the narrative to the 1979 revolution with very few historical additions to the original text). Jewish history is recounted through a lens of communal riots and anti-Jewish decrees.

In the past couple of decades, Middle East studies scholars have published myriad books that have revisited Jewish histories employing new integrative methodologies and perspectives. Orit Bashkin has described this trend as “the Middle Eastern Shift” in Jewish studies.Footnote 23 It is an apt conceptualization to describe a new historiographical approach that focuses on conditions that enabled Jewish communities to integrate into the national and imperial frameworks of modern MENA societies rather than through the fundamental lens of purported ancient Jewish–Muslim rivalry. Following the appearance of this scholarship, our understanding of Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, the Ottoman Empire, and even Mandatory Palestine and early statehood Israel has fundamentally changed.Footnote 24

For various reasons that are connected to the nature of Iranian studies and Jewish studies, these otherwise field-wide methodological changes did not occur in studies of Iranian Jewish communities. Instead, this scholarship preserved what Hamid Dabashi has called “the horrid and persistent anti-Jewish trait endemic in Iranian popular culture and even in Persian literature,” while overlooking additional and sometimes contradictory phenomena.Footnote 25 In doing so, it continued to produce the same type of superficial scholarship that permits Iranian Jews only a nominal existence as silent dhimmis, without agency.Footnote 26

Jewish journalism in Iran provides a neglected gateway to analysis of the developments and transformations that the Jewish communities experienced across the 20th and 21st centuries. I draw on two main publications. The first, Tamuz (named after the Hebrew month of July), was published from 1979 to 1986 by the Association of Jewish Iranian Intellectuals (AJII; Jami‘a-i Rawshanfikran-i Kalimi-yi Iran). The leadership of AJII was the de facto leadership of the Jewish community from March 1978 onward.Footnote 27 The second, Ofeq Bina (in Hebrew, Horizons of Wisdom) has appeared regularly since 1999 and continues to serve as the official publication of the Jewish community in Iran. This research focuses on those printed publications, and they provide a certain vantage point on the sectors in the community that are in direct conversation with the state. This can limit as much as it reveals. On the one hand, these resources may operate under tight constraints and navigate pressures from the community, regime, and general society; on the other, dissenting voices sound louder in this context.

Prior to the 1979 revolution, even as Iran's Jewish population of 80,000 to 100,000 inhabitants remained externally unaltered, internally it experienced profound transformations due to the emigration of lower-income Jews to Israel in the late 1940s and early 1950s, as well as the rapid urbanization and economic integration of the Jewish middle class. Indeed, Israel played an oversize role in shaping how Iran's Jewish communities were perceived both inside and outside the Middle East. Interestingly, these transformations share profound resemblance to what the Christian Armenians in Iran experienced in the same period.Footnote 28 Until the shah's overthrow, because of the tight-knit alliance between the two countries, Israel portrayed Iran as a modern society in which Jewish communities could thrive, just like any other modern Western society. After the revolution Jewish existence in Iran became almost an oxymoron, according to the Israeli narrative.Footnote 29

During the first years of statehood, Israel's emissaries worked relentlessly, with varying levels of success, to register Jews for aliya (immigration to Israel). Most of the Jews who immigrated from 1948 to 1953 were among the poorest of the Iranian Jewish communities and from the geographical and social periphery of Iran.Footnote 30 Shortly thereafter, partially thanks to this emigration, but also to wider social, cultural, and economic transformations—urbanization, the emergence of a new middle class and bourgeoisie, industrialization, and changes in commerce and bureaucracy—Iranian Jews experienced an unprecedented elevation of their status. Reflecting this change, Yossef Ness, the director of the Aliya Department in Tehran, wrote in a 1961 telegram to the chair of the Organization Department of the Jewish Agency, Tzvi Luria, “We have to take into consideration that under normal political conditions in this country, many years will pass before the majority of Jews will immigrate to Israel. In that sense, Persia is not different from other Western countries whose Jews would rather stay in the diaspora.”Footnote 31

Between 1948 and 1961, Israel's view shifted from one in which the Jewish state was “rescuing” the Iranian Jews to a perception of Iran as similar to other Western industrial welfare states. Accordingly, shortly thereafter, the Jewish Agency decided to cease its operation of encouraging Jews to immigrate to Israel. In the late 1970s, however, as violent demonstrations presaged the revolution that would overthrow Mohammad Reza Shah, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin (r. 1977–83) deployed Moshe Katsav, a young member of the Knesset and a native of Iran (and future president of Israel) on a fact-finding mission to Iran. Stunning Katsav and members of Begin's government, who began evoking 1930s Germany, the Iranian Jews did not view the revolutionary events as reason for Israel, or anyone else, to rescue them. So, even as public discourse in Israel and Katsav, in his many reports from Iran, sought to depict the situation in Iran as paralleling that of 1930s Germany, Iranian Jews refused to play the expected role of victim.Footnote 32

Even before Ruhollah Khomeini's return to Iran in February 1979, the Israeli press and leadership invoked the loaded terminology of European Jewish history. Israeli media reported on “fears of the establishment of concentration camps for Jews in Iran.”Footnote 33 Prime Minister Begin regularly used Holocaust analogies.Footnote 34 With Holocaust memory now playing such a profound role in Israeli society, the events in Iran—depicted in Holocaust-related jargon—allowed bringing current day Mizrahi communities into the folds of the Holocaust story.Footnote 35

In February 1980, Israeli president Itzhak Navon hosted a discussion on the Jews of Iran. Professor Amnon Netzer, a noted scholar of Iranian studies in Israel, wrote in preparation for this discussion that:

Only in late 1978 and early 1979 did we in Israel and around the world get the impression that Iran's Jewry is in grave danger. Some even predicted horrific occurrences that included extermination camps for the Jews of Iran. Now, a year after the revolution, there are many question marks. What is the nature of the current regime in Iran? Why in fact was there no mass exodus of Jews while they were free to leave the country? Why did the majority of those who left Iran (between 20,000-30,000) choose not to make aliya to Israel? We are astounded by the phenomenon that hundreds of Jews (if not more than that) leave Iran every month and then return to Iran, without any interruption on behalf of Iran's government.Footnote 36

Yet again, we see that experts could not explain the unpredictable (and as it was perceived, unreasonable) behavior of Jews who could leave Iran, who chose not to immigrate to Israel, and moreover who could reenter Iran, all while the revolutionary government was fully aware of their movements and did nothing to stop it.

The Politicization of Iranian Jews (1941–1979)

Missing from the Israeli story was a realization that Jews in Iran had not been mere bystanders or passive participants in Iranian society and politics. Jewish activism and participation in leftist parties had been prevalent in Iran since 1941, to the extent that they were overrepresented in some circles; even the British characterized the communist Tudeh party as one comprised of “Armenians, Jews, and Caucasian émigrés.”Footnote 37 Many such politically active Jews (not the majority by any stretch of the word, but enough to constitute a visible minority) remained active in the 1970s leading up to the revolution. I would argue that this political involvement, be it on the side of the Tudeh, other revolutionary parties, or even pro-Shah or Iranian Zionist parties, strengthened their ties and commitment to the country, culture, and society. The Iranian Zionist activism reflected Zionism as a particular cultural movement with roots in Iranian Jewish society.

At the time, the Tudeh was one of the most popular political parties among all Iranians, in terms of membership and sympathizers.Footnote 38 In the 1950s several Jewish newspapers and publications promoted the party's political line, and they increasingly became more important and more popular. Newspapers like Nissan (named after the Hebrew month of April) and Bani-Adam (Human Beings; there are many cultural references to Bani Adam in Persian classic poetry) supported and facilitated the formation of Jewish political activism. Their work cultivated a national consciousness that exceeded the boundaries of the Jewish community alone. After 1953, Jews and Armenians continued to be disproportionately overrepresented in various underground political parties and anti-Shah circles.Footnote 39 On par with their political activism during the Pahlavi period, Jews were part of 1970s revolutionary movement groups in addition to the Tudeh, such as student organizations and the Association of Jewish Iranian Intellectuals. They, too, took to the streets and participated in political demonstrations supporting a wide variety of revolutionary movements.

It is difficult to quantify the extent of Jewish participation in the revolutionary movement, but sources suggest that it was not inconsequential. In March 1978, nine months before the shah left Iran, Jewish radicals, some of whom were socialists and republicans, won the elections for the leadership of the central organization of the Jewish communities, defeating the old guard establishment that was identified closely with the shah and his alliance with Israel.Footnote 40 These activists formed the aforementioned AJII. Later in 1978, particularly in September and December when the demonstrations grew larger and more frequent, there are multiple reports of thousands of Jewish protestors marching in Tehran, and the Jewish hospital in the city operated rescue teams together with the leadership of the revolutionary movement.Footnote 41 It should be noted that from that moment on there were no official voices in the community in support of Zionism. There were myriad motivations and reasons for Jews (and non-Jews) to support the revolution, some more prosaic than others. In her memoir, Roya Hakakian provides a glimpse into how a Jewish teenage girl from a middle-class family in Tehran understood the revolution swirling around her: “Not to those screaming strangers in the car, but to the streets, to their rapturous cascade that beckoned me with undeniable clarity, I belonged. To the revolution I belonged. To the rage that unlike me had broken free. It would guide me as no one else could, raise me as no one else knew how. And to be its daughter, I would emulate it in any way I could.”Footnote 42

Following the revolution's victory and the early days of the republic, Jews—just like non-Jews—tried to navigate their way in the rapidly changing society. In the months immediately following the revolution, chaos reigned in both the government and in the streets. The revolutionary courts executed hundreds of the shah's loyalists, power struggles ensued between the competing revolutionary movements, and there was a broad attempt to erase any evidence of the former Pahlavi domestic and foreign policies. One of the highest profile trials and executions was that of the industrialist, philanthropist, and Jewish community leader, Habib Elghanian, on 9 May 1979. Given the clearly fabricated charges of being a “friend of God's enemies, spying for Israel, and spreading corruption on earth,” Iranian Jews feared that if the new government executed Elghanian no Jews would be immune from such treatment.Footnote 43 Shortly afterward, the Iranian Jewish leader Hakham Shofet led a small delegation to Qom to meet with Ayatollah Khomeini to seek clarification. The meeting helped to allay the Jewish community's concerns. In his proclamation, Khomeini acknowledged the deep roots of the Jewish communities in Iran, underscored the elements of monotheism present in both Judaism and Islam, and distinguished between Zionism and Judaism: “We know that the Iranian Jews are not Zionist. We [and the Jews] together are against Zionism. . . . They [the Zionists] are not Jews! They are politicians that claim to work in the name of Judaism, but they hate Jews. . . . The Jews, as the other communities, are part of Iran, and Islam treats them all fairly.”Footnote 44

At the same time, this societal chaos produced euphoric dreams for the postrevolutionary republic. In less than two years, from February 1979 to summer 1980, Iran witnessed its broadest political participation and freedom of the press that resulted in hundreds of new publications, which in turn helped to inform and shape public opinion. Such participation and euphoria were enjoyed by all the religious minorities, including the Jews.

The Jewish community's leadership now had direct relations with the revolutionary leaders, and they were given a place to represent the Jews and other religious minorities in shaping the character of the new republic. One of its community's leaders, ‘Aziz Daneshrad, an ex-Tudeh activist, was elected to represent the Jews in the Constitutional Experts Council (Majlis Khobrigan-i Qanun-i Asasi). The council's main role was to write the republic's new constitution and bring it forth for referendum.Footnote 45 At the same time that news reports in Israel and around the world claimed that Iran was building extermination camps for Iranian Jews, Daneshrad as a sitting member of the council raised the idea of revoking the reserved seat for the religious minorities, allowing minority candidates to compete in the general party lists. To his disappointment, the measure was not approved.

The Public Sphere and Jewish Press in Postrevolutionary Iran

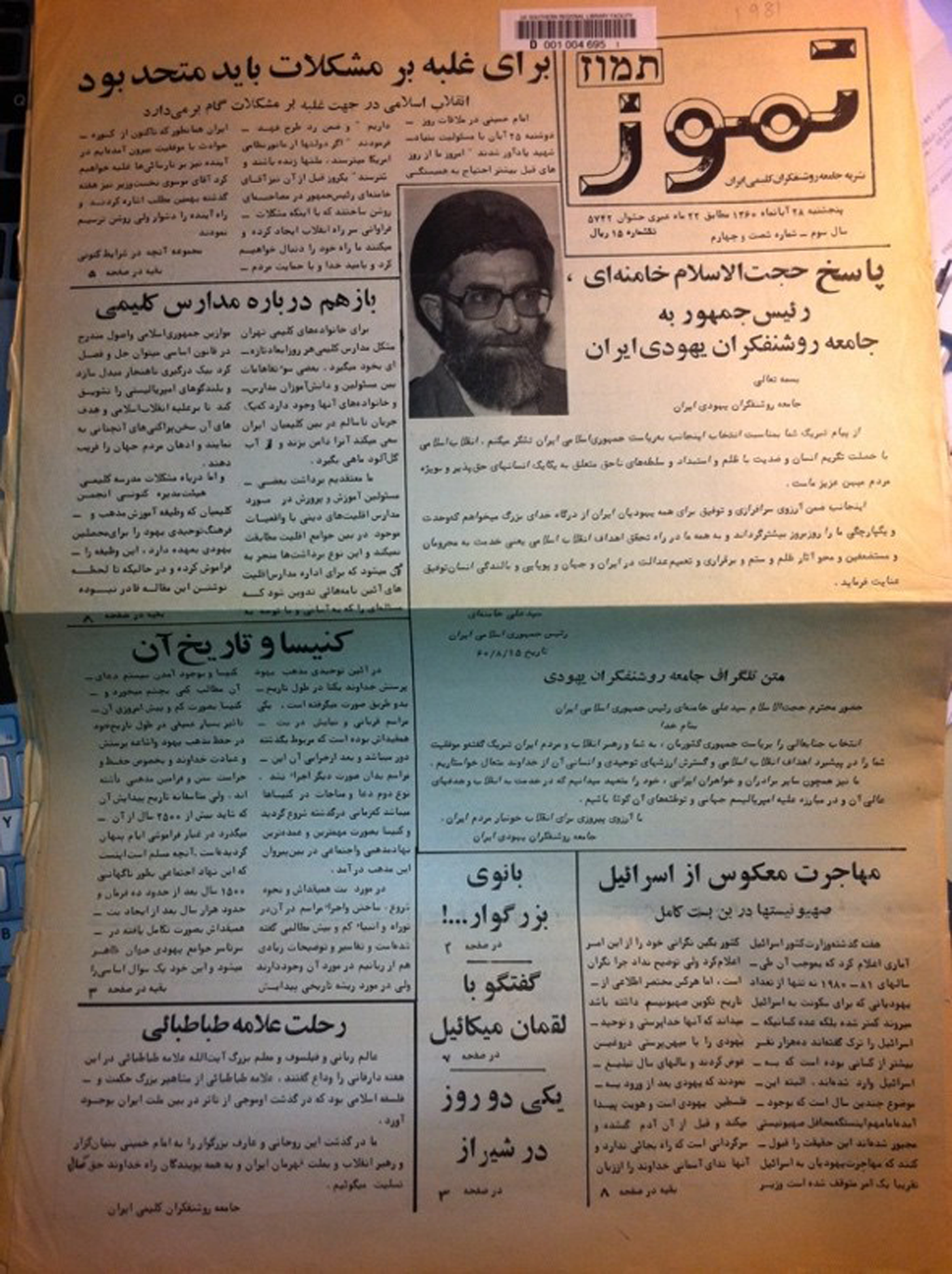

Daneshrad, for his part, did share his insights from the council's discussions and debates in Tamuz, the official publication of the AJII. Tamuz resembled previous generations of leftist Jewish publications in content and format. In its reporting, it promoted support for the revolution and the notion that being revolutionary was essentially Jewish. It also featured close analysis of the Jewish communities of Iran, Israel, and the rest of the world, while contextualizing this analysis to current events in Iran, and even served as a platform for communication between the republic's leadership and the Jewish population (Fig. 1). Daneshrad presented the AJII's position, and by proxy, the religious minority communities’ (Jewish, Christian, and Zoroastrian) position on the proposed constitution:

In article 50 of the constitution, it is written that Iranian Zoroastrians and Jews will have one representative elected, and Christians will elect two representatives. Such a proposition is drawn from years of tyranny and strangulation. Our country's strength and character are dependent upon the coexistence of the religious minorities and the national majority . . . AJII believes that every Iranian, no matter their religion, ethnicity, or race, must have the right to vote. This right must be protected and implemented by a mutual understanding and respect between all ethnic groups and religious followers in the country.Footnote 46

Figure 1. The front page of Tamuz, 19 November 1981 (28 Aban 1360). In the photo, the newly elected president (today's Supreme Leader) Hojjat al-Islam ‘Ali Khamenei responds to the Association of Jewish Iranian Intellectuals.

Daneshrad did not limit himself to dealing with Jewish or minorities affairs. He was active on economic and social issues, pronouncing the state's responsibility to workers and the poor. It was during the council's debate on Article 14 of the constitution—the article that officially recognizes Iran's religious minorities—that he proved how crucial his mission of representing minority rights was at this stage. During the debate, the deputy from Baluchistan, Molavi ‘Abdol-‘Aziz, argued against Iran's decision to recognize the official religions of Israel and America (‘Abdol-‘Aziz spoke about countries that were nominally enemies of Iran) while not recognizing his religion, Sunni Islam. Ayatollah Beheshti, the chair of this session, reminded council members that religious minorities had always been a part of Iranian society and allowed Daneshrad to respond. Daneshrad's response was emotional and agitated. He exclaimed: “I am loyal to this country, I was born Iranian, my ancestors have been in Iran for 2700 years, and I will be buried in Iran.” He then asserted that “the Israeli government is a secularist government, and its foundation is not based on religion but on the politics of usurpation which is hated by all believing Jews.”Footnote 47 The constitution was amended several times by referendum, with Iranian Jews’ place among other recognized minorities preserved. Their representation in the Majlis was also safeguarded. The year immediately following the revolution brought the most horrific revolutionary developments, such as the revolutionary trials and mass executions, assassinations, and general political instability.Footnote 48 At the same time, we should recall the feeling of institutional utopian chaos that allowed Iranians—Shi‘i Muslims and minorities—to exercise their imaginations, hopes, and fears of what the postrevolutionary republic was going to look like. It also cemented the notion that they had a say in the shaping of their future, based on past and present experiences. The next challenge would be how to most strategically redefine their Jewish and Iranian identities within the Islamic Republic.

Navigating the Maze of Identities: Being Jewish and Iranian in the Islamic Republic

Once the Islamic Republic was formalized in 1979/80, the state forced all its subjects to redefine the boundaries of their religious identity, whether they were Muslim or a recognized religious minority. Unrecognized minorities, such as the Baha'i, were denied any option for recognition within the framework of the Islamic Republic, and would be persecuted for their religious affiliation.Footnote 49 Muslims had to find their place on a spectrum of acceptable positions within Islam, as interpreted by Iran's religious leadership, even as the political winds shifted between inclusivity and exclusivity. Recognized minorities faced multiple challenges, even related to practicing their religion and their political and religious identification.Footnote 50 Categorized as different due to religious affiliation, Iranian national identity was the only acceptable path into the new society.

In the early 1980s, the Iranian Jewish leadership defined its political and national belonging on two levels. First, they distanced themselves completely from any identification with Israel, while stressing the long-time position of the Jewish community's leaders against Zionism. Then, with the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq war in September 1980, they showed unequivocal support for the war effort. To underscore their support, community leaders worked through synagogues and other social establishments to encourage enlistment in the Iranian army.Footnote 51 They presented the act of volunteering as an opportunity to make a blood covenant with Iran's Muslim majority. Tamuz, for example, published an article paralleling the actions of young Jewish activists during the revolution to those of joining the military efforts in defending the homeland: “Jewish Iranian youth, before and after 22 Bahman 1357 [February 11, 1979], joined their [Muslim] compatriots in the struggle against the Shah's regime, and in this way dedicated martyrs to the revolution [Shohada-yi taqdim beh enqelab namudand]. After the victory of the Islamic revolution and the stabilizing of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Jewish youth have been part of every arena from participation in the Construction Jihad [Jihad Sazendagi] to helping our brothers and sisters with the support they needed on the front in the battles against the aggressor regime of Iraq in every place and showed their commitment to the revolution.”Footnote 52

Tamuz repeatedly published stories on the failures of Zionism and connected Israeli aggression and the banishment of the Palestinians and the Mizrahi Jews to the ideological failure of Zionism. In the 1980s Tamuz writers leveled scathing criticisms at Israel for annexing Jerusalem and the Golan Heights and for the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and noted that in 1981, for the first time in Israel's history, more people emigrated from than immigrated to Israel. In fact, some of these migrants who had initially left Iran returned to the war-stricken country.Footnote 53

In 1986 Tamuz ceased publication. Iran entered its last two years of the war with Iraq (1986–88), coped with the death of Khomeini (1989), and struggled with the long process of postwar recovery. In those years, there were a few waves of emigration, mostly of middle-class families, among them many Jews. Aside from the obvious motivations of political instability, postrevolutionary violence, the fears of an unknown future, and the ongoing war with Iraq, we can also read this as an exodus of the shrinking middle class. After eight years of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani's presidency (1989–97), Sayyed Mohammad Khatami (r. 1997–2005) was elected on behalf of the reformist camp. His election was characterized by support for minority rights in civil society, discourse on human and civil rights, and attempts to lead policies of internal dialogue in Iran and a dialogue between Iran and the world. Another by-product was the appearance of myriad publications—mostly liberal leaning.Footnote 54 In that spirit, we see the start of the Jewish establishment's new publication in Tehran, Ofeq Bina.

Ofeq Bina first appeared in early 1999 as the official newspaper of the Jewish establishment (in its first year it was published under the shorter title Bina). In many ways it represents the intellectual reincarnation of previous Jewish Iranian publications. Some editorial board members had been staff members on Tamuz. The cover of the first issue of Ofeq Bina (March-April 1999/Farvardin 1378) conveyed its founders’ intentions. The title Bina appears in Persian and Hebrew along with the Hebrew and Persian date and a classic Persian miniature with the word “Bereshit” (Genesis) in Hebrew at the center. At the bottom of the cover page is written: “Religious, Cultural, and News Magazine of the Jewish Association in Tehran” (Nashriyeh dinni-farhangi-khabari argan-i anjoman-i kalimian-i Tihran; Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Cover of Bina (March-April 1999/Farvardin 1378).

The founders of Ofeq Bina perceived its role to be educational, but with a political bent. Reflecting the liberalizing trends within Iran, an early editorial explained how they chose the magazine's name.Footnote 55 Bina in Hebrew means wisdom and reason, principles the editors hoped to inculcate among readers.Footnote 56 Its educational mission encompassed the Jewish community within the Islamic Republic (political orientation, community and social organizing, national matters); Jewish culture in Iran (history, literature, contemporary culture, Hebrew learning); and Jewish history and culture around the world. In the first issues of Bina, readers could engage with a fascinating introductory article about Spinoza's philosophy, an article on the American Jewish violin maestro Yehudi Menuhin, and an article on the famed Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem accompanied by a translation of one of his short stories.Footnote 57

As part of its political project, Ofeq Bina published news items and op-eds by the editors, with regular and guest columnists who described existing opportunities for religious minorities to gain influence in Iran's national and local political systems; they presented debates and interviews regarding the constitutionally protected rights of minorities within the framework of an Islamic discourse on human rights.Footnote 58 At the same time, the magazine tried to highlight the Jews as part of Iran's national community. For example, the community establishment published announcements prior to the 22 Bahman celebrations of the 20th anniversary of the revolution.Footnote 59 It was reported that the Jewish team won the national religious minorities’ tournaments in soccer, basketball, volleyball, and table tennis.Footnote 60 This shows that Jews and other recognized religious minorities held active roles during the national holidays as well, albeit in a place designated for them as recognized religious minorities within the Islamic Republic.

Ofeq Bina also featured essays highlighting Jewish-specific topics. Essays on history and politics encouraged discussions on political identity. Essays on the place of the Jews in Iranian politics, among other religious minorities and in relation to the majority society, helped to broaden the context for their autonomous existence within Iranian society. And of course, featured essays were included on topics that were unique to their history and situation on matters such as Iranian nationalism, Judaism, and Zionism. Over the years, Ofeq Bina presented essays such as “Iran and the Question of Palestine,” which discussed at length the complex history of Iranian Jews with the Zionist movement, and “Eretz Yisrael.” In this two-part essay, Harun Yeshayaee, a leading Iranian Jewish thinker, discussed the sanctity of that land to the three Abrahamic religions, the challenges that this mutual sanctity raises, and the history of the Zionist movement within imperial institutions, the Alliance Israelite Universelle, the Qajar monarchy's relations with Europe, and the ongoing relations between Jews and Muslims in Iran from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century and the Balfour Declaration.Footnote 61

In the second part of his essay, Yeshayaee addressed the stance of Iranian Jews’ on Zionism after the establishment of Israel: “For many years and until today, in terms of shape and substance [read: numbers], the migration of Iranian Jews to Palestine did not satisfy the Zionist authorities.”Footnote 62 The article emphasizes how, despite great efforts and investment, the Jews of Iran did not respond to the call of Zionism as they were expected to do, contrary to the assumption of the Zionist establishment. It is interesting to consider the space that was given to polemic essays that addressed issues related to Zionism. Presumably, Zionism had no foothold among the magazine writers, editor, or readership. It is possible that, in addition to a nod to the potential censor, the staffers were aware of the dangers of guilt by association to Zionism and tried to preempt it by establishing a long record of essays highlighting the profound differences between Judaism and Zionism.

In another essay, the same author discussed “Zionism in Theory and Practice: The Profound Difference between Prophetic Judaism and Political Zionism.” The article explains the rise of Zionism in the context of anti-Semitic persecution in Europe and presents Zionism as a movement of liberation, like many other similar movements of that time. Yeshayaee argued that Zionism did not have an inherent evil core (although this was certainly a mainstream view of Zionism in the Islamic Republic), but took Jewish symbols and filled them with a different substance, a political rather than religious meaning.

Side by side with its efforts to differentiate between Judaism and Zionism in Iran and abroad, the community leadership went out of its way to portray Iranian Jews as deeply rooted in their country and as an integral part of Iranian society. The presidency of Khatami provided them with several opportunities to demonstrate their commitment to Iran and its republic. Khatami's campaign was part of a democratic and popular movement that crossed sectors in Iranian society and mobilized different demographics, especially the younger generations, who had become a major voting bloc.Footnote 63 His reformist agenda and campaign promises of a “discourse of civilizations” (Guftegu-yi tamadun'ha), supporting civil society and an interreligious dialogue, raised hopes among minorities of gaining more social and political rights.Footnote 64 It is no wonder, then, that Ofeq Bina started to publish during this period. The Iranian cultural and civil establishment was part of this new spirit and did not wait for direction. Nor did its leaders need reminders of Khomeini's promise that minorities, as a vital part of the nation–state, would be protected; in fact, the government began implementing some of these core principles. In 1999, as part of the prestigious Fajr Film Festival marking the 20th anniversary of the revolution, Harun Yeshayaee received a lifetime achievement award for his decades-long work as a film producer and his influence on Iranian cinema.Footnote 65 Iranian Jews considered the awarding of this prestigious prize to Yeshayaee a real breakthrough in community relations with the Iranian government. This is not to suggest that all the barriers were removed. In June 1999, thirteen Jews from Shiraz were arrested for allegedly spying for Israel. Some of them were released immediately afterward, and others were sentenced to short prison terms, with the last prisoner released in 2003.Footnote 66 This story indicated the possibility of unforeseen, random changes in the level of freedoms and personal security Iranian Jews enjoyed, and the fragility that might factor in when they were used, however reluctantly, for geopolitical purposes.

On 11 August 2000, President Khatami met with members of the community. Religious and political leaders were in attendance, as were Jewish students and the Jewish deputy of the Majlis. Khatami expanded on his discourse of civilizations and the partnership of those who believe in one God, and even spoke about Jewish philosophy and the writings of Philo. The important issues, however, Khatami saved for later: “You defended this country shoulder-to-shoulder with Muslims and other citizens during the Sacred Defense [Dif'a muqades, the Iran–Iraq War], and today we can work together in building an independent and proud Iran.”Footnote 67 There is great significance in Khatami's recognition of the Jews’ participation in the war. Including the Jews in the narrative of the Sacred Defense was a major step in their integration with the greater narrative of the revolution and its subsequent nation-building project. In fact, this war was viewed as the formative experience of the pro-revolution generation. Khatami was also responsible for another major step when, on 8 February 2003, he became the first sitting president since the revolution to conduct an official visit to a synagogue, the Youssef-Abad synagogue in Tehran (Figs. 3, 4).Footnote 68

Figure 3. President Khatami visiting Youssef-Abad synagogue in Tehran, 8 February 2003. Image courtesy of Va'ad HaKehila Li-Yehudei Tehran.

Figure 4. President Khatami being shown the Torah scroll by Iran's chief rabbi, Youssef Kohan Hamedani Z”L, during his 2003 visit to the Youssef-Abad synagogue. Image courtesy of Va'ad HaKehila Li-Yehudei Tehran.

In 2005, following Khatami's second term, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president. After two presidents and four terms that had perhaps signaled that the revolution was becoming institutionalized and that the reformist camp might be able to counteract the religious conservative establishment, Ahmadinejad represented a counterpoint to the reformist agenda and its platform.Footnote 69 With his confrontational approach, Ahmadinejad tried to position Iran at the frontlines of the struggle against Western and American hegemony. One of the tools he used was the Iranian nuclear project, and by promoting Iran's attempts at nuclearization, he publicly and directly challenged the United States. He reinstated regional and international alliances with countries such as China, Cuba, and Venezuela. These new allies reclaimed their role in Cold War era trade agreements. Last, he challenged the foundations of the liberal post–World War II world order by questioning the authenticity of the Holocaust. Through a series of provocative speeches, an international conference (An International Convention to the Study of the Holocaust: Points of View from Around the World), and a controversial cartoon competition, he positioned Holocaust denial (in the guise of examining facts) as a major component of his administration's prioritized policy issues. In fact, this policy played a dominant role in meetings with Western statesmen, diplomats, and journalists.Footnote 70

If, as has been argued, Iranian Jews have waited in a taqiya mode, careful to avoid confrontation at all costs, the response of Iran's Jewish leadership countered their prescribed reactive role. Morris Moatamed, then the Jewish deputy in the Majlis, attacked Ahmadinejad in interviews, public letters, and even in the parliament. In an interview with the BBC, Moatamed said that “hosting this convention after [having had] the cartoon contest on the Holocaust puts pressure on Jews around the world and creates the wrong idea about Iran among nations and governments.”Footnote 71 Moatamed's letter, written in Persian, was even more pointed. Referring to the president and other Holocaust deniers, he said, “They use the cover of anti-Zionism to express their anti-Semitic views and to humiliate the religious and moral values of the Jews.”Footnote 72 Harun Yeshayaee, who served as the head of the Jewish community, penned a public letter that was published by leading newspapers in Iran, in which he assailed the president and his motives:

How can one forget that the declared main principle of the Nazi party and army was to cleanse Europe of its Jews and its racist theories of fascism? He can read Adolf Hitler's book Mein Kampf or the existing speeches of Goebbels and Himmler. How is it possible that there is so much unshakable evidence, documented evidence of the murder of Jews during the Second World War, and instead of accepting this evidence, Ahmadinejad accepts deceitful speeches of a few people? The Holocaust is not a fiction, in the same way that Saddam Hossein's genocide in Halabja is not a fiction, just like the killing of Palestinians and Lebanese in Sabra and Shatila by the murderer [Minister of Defense Ariel] Sharon is not a fiction, and the killing of Muslims in the Balkans and everything that is going on today in Afghanistan, and Iraq, and Sudan, none of it is fiction . . . you need to worry that neo-Nazi European leaders who today burn down houses of black people and raid Muslim neighborhoods, tomorrow may instigate similar treatment of Muslims, comparable to actions that occurred during the Holocaust.Footnote 73

The Holocaust and its history remained an issue of debate during Ahmadinejad's presidency. During the televised presidential debate in 2009, the leader of the reformist movement, Mir Hossein Moussavi, confronted Ahmadinejad for his Holocaust denial and argued that the president's stance disgraced Iran and created unnecessary friction with Iran's allies.Footnote 74 Harun Yeshayaee himself continued to write on this issue for some time, and in 2013 he published an article in Sharq (East), the popular newspaper identified with the reformist camp, under the title “Afsaneh ya Vaqiyat” (Myth or Fact). Yeshayaee reminded readers that there was no shortage of scholarship and research on the Holocaust or Zionism's manipulation of Holocaust history for its own benefit. He challenged the denialists’ assertions that the Holocaust was organized by the Jewish lobby in Europe or America. Hitler's death squads operated with the expressed goal of cleansing Europe of its Jewry, he countered, and did not hesitate to kill Jews who had recently converted, or even those who had converted generations earlier. Yeshayaee ended the article by removing Zionism and Zionist politics from the narrative. The Nazis “killed the Jews because of their race and religious beliefs, and did not care about the politics of the Jews.”Footnote 75

Conclusion: New Narratives

In the years following the 1979 revolution, the overwhelming majority of Iranian Jews left the country. Most of them emigrated to the United States, others to Israel, and still others to Europe and other destinations. The forced overlap between the “Islamic” and “Iranian” parts of national identity made it much harder to stay in Iran as Jews, but not impossible.Footnote 76 Iran's recognized minorities (Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians) were by and large spared the ordeals faced by the Baha'i communities in Iran: persecution, arrests, and even executions; closure of institutions; and reappropriation of property and assets. Yet these recognized minorities understood that if the government could afflict such horrors upon the Baha'is the relative tolerance toward them also might have limits.

Today, forty years after the revolution, we know that no concentration camps were established for the Jews of Iran in the aftermath of the revolution. We know that Jews were not limited in their movements in Iran, nor were they banned from leaving the country (traveling abroad became harder in general, and some Jews faced more hardships than others, but the fact that about 60,000 of them left in the first two decades after the revolution adds much-needed context). Still, official Israeli speakers have characterized the past four decades of the Islamic Republic of Iran as “Germany in 1938.”Footnote 77 Public conversations continue to shape academic discourse and scholarship on Iran and Iranian Jews. In a prevailing atmosphere of mutual suspicion, a fabricated story of a group of Iranian exiles in Canada forcing minorities to wear a yellow star was reported as a fait accompli in the Israeli press, generating outrage from voices on both the left and the right of the Israeli political map.Footnote 78 Iranian Jews are not hiding in taqiya mode. In present-day Iran, those who remain speak up against injustices. They express a desire to be part of the Iranian nation and maintain independent positions relative to the Islamic Republic, as well as to Israel and Jewish issues worldwide. The Iranian Jewish response to an ongoing discourse of “rescue” has been far less enthusiastic than expected.Footnote 79 In general, Iranian Jews living in Iran want to remain Jewish and Iranian without compromising any component of their identity.

After Ahmadinejad's two presidential terms, Iranians elected a pragmatist, Hassan Rouhani. Under his leadership (r. 2013–21), Jews experienced a number of political and cultural achievements. In December 2014, the government unveiled a monument with Persian and Hebrew text that commemorated the Jewish soldiers who sacrificed their lives during the Iran–Iraq war.Footnote 80 In addition, the Majlis passed new laws that corrected prevailing inheritance laws, which prioritized Muslim heirs over their Jewish relatives, and another law that excused Jewish students in public schools from attending classes on Shabbat.Footnote 81 Under Rouhani's tenure, the president and his foreign minister made it a tradition to bless the Iranian Jewish community on their official Twitter accounts on Rosh HaShana.Footnote 82 In one of his many Twitter threads, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif referred to the former president's Holocaust denial and countered: “Iran never denied the Holocaust. The man who denied the Holocaust is now gone. Happy New Year.”Footnote 83 Although Zarif meant to draw a line between Ahmadinejad as the most prominent Holocaust denier and the Rouhani administration that he (Zarif) was part of, it is important to note that Holocaust denial remains prevalent in the ranks of the Iranian government. Iran's Supreme Leader, ‘Ali Khamenei, has himself engaged in Holocaust denial and such references remain on his social media and official website.Footnote 84 Zarif's point, however, has some merit in that Holocaust denial is not as dominant as in other Middle Eastern societies.Footnote 85 Even during Ahmadinejad's presidency, state-run TV aired the drama Zero Degree Turn, based on the story of Abdol Hossein Sardari, the Iranian diplomat in Nazi-occupied Paris who forged passports for French Jews.Footnote 86

Historiography needs to reflect the many streams of Jewish realities and experiences, especially throughout the turbulent eras of the 20th and 21st centuries. Presenting complex and nuanced narratives should not and can not whitewash the brutality and crimes of the Islamic Republic toward its minorities, and especially the persecution of those of the Bahai'i faith who do not have even the nominal legal protection other minorities enjoy. Rather, these narratives and complex histories help readers see the ways in which Jews in Iran (and other places as well) have sought to overcome legal and social hardships and reach, despite pressure from powerful forces, a well-rounded definition of their ethnic, religious, and national identities. Presenting simplistic narratives, let alone conjoining them into one congruent and self-serving narrative, will be disastrous to our attempts to understand Iran, Jewish history in Iran, and even Jewish history in the contemporary Middle East. Iranian Jews speak and write, and their views, opinions, struggles, and actions can represent their complex experiences of living in Iran. Scholars can understand Iran and Iranian Jews better when they listen to Iranian Jews when they speak and write about their experiences of being Kalimian in Iran.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank David Atwill, Arash Azizi, James Barrry, Michelle Campos, Alma Rachel Heckman, Chris Heaney, Afshin Marashi, Ran Shauli, Tamir Sorek, and Murat C. Yildiz, who read earlier versions of this article; the IJMES anonymous reviewers; and the Penn State Humanities Institute, where I was able to complete the research and writing of this article.