On October 30, 1950, the Turkish children's magazine Çocuk Postası (Children's Post) published its first installment of the comic strip “Spies of the Atom!” (Atom Casusları!), which was published weekly between October 1950 and January 1951. Set in London, this detective story revolved around the attempts of Special Agent “X” from Scotland Yard and his assistant Dick Perry to retrieve the physicist Reginald Bradley's plans for “weaponizing the atom” after the latter was killed by an unknown masked intruder during a robbery.Footnote 1 This comic was the first demonstration that the Cold War had reached Turkish children's magazines, but it was not the only one. Throughout the 1950s, the Cold War was omnipresent in Turkish children's magazines. Analyzing this can tell us a great deal about the ideological atmosphere in which Turkish children grew up as part of this global conflict and shed light on the place allocated for children by adults in this new political struggle.

In the last three decades, child-centered history has attracted increased research attention. These studies aim to explore and understand children's worlds and their emotions by constructing children and the history of childhood as a separate field of inquiry. Cultural and gender or feminist studies of children in the Middle East have recognized children as active agents in historical narratives, and they are researched as historical subjects in their own right.Footnote 2 However, research on children and childhood in the Middle East is still evolving. Although there was a growing interest in children in the Middle East in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, historical research on the Cold War period remains scarce.Footnote 3

Cangül Örnek and Çağdas Üngör, the editors of Turkey in the Cold War: Ideology and Culture, point out that since the 1990s scholarly efforts to examine the social, cultural, and ideological dimensions of the Cold War have intensified. The growing literature on the “cultural Cold War” has opened new avenues of Cold War historiography, which was previously confined to a narrow strategic perspective. This new literature has shed light on previously neglected spheres of Cold War confrontations, ranging from popular culture such as movies, books, music, exhibitions, and media to art and even sports encounters. Similarly, the experiences of daily public life have assumed new political significance in the Cold War context.Footnote 4

In her book Little Cold Warriors: American Childhood in the 1950s, Victoria M. Grieve argues that over the past decade historians of American childhood and foreign relations have begun to explore how different groups of Americans, including children, experienced and participated in Cold War politics. According to her, American children actively fought the Cold War on the home front and abroad in many ways: watching their heroes battle communism on television, in the movies, and in comic books; practicing safety drills; joining civil preparedness groups; and helping to build and stock bomb shelters in the backyard. Children also collected coins for UNICEF, exchanged art with other children around the world, prepared for nuclear war through the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, raised funds for Radio Free Europe, sent clothing to refugee children, and donated books to restock the diminished library shelves of war-torn Europe.Footnote 5

Although the experiences of children in the United States during the Cold War have received much scholarly attention, including cultural products designated for children, such as literature, television series, movies, magazines, and comics, their experiences in other parts of the world remain underresearched.Footnote 6 This should not come as a surprise, because, according to Rana Mitter and Patrick Major, many studies of the Cold War are geographically biased, focusing on the United States and Europe and neglecting other areas such as the Middle East and the Far East, consigning themes, such as Cold War “home fronts,” nuclear fears, and the production and reception of propaganda and intellectual traffic, to other places.Footnote 7

My main purpose in this article is to explore how Turkish children's magazines were impacted by the new Cold War realities and the role that they played in educating and indoctrinating children to support Turkey's pro-Western stance during the early part of the Cold War in various ways. The first was through the production of new local content in the form of articles, stories, and comics, which introduced terms such as the “Cold War” and “communism” and institutions such as the United Nations and NATO, and depicted the Turkish experience of the Cold War as part of the Western camp. The most common method was to depict the Turkish contribution to the Korean War.Footnote 8 Stories and comics also reflected common anxieties and uncertainty typical of the Cold War, including fear of espionage and fifth columns. The second approach was much more subtle and was based on the publication of American comics, translated into Turkish, and in some cases repurposing and rewriting existing comics, adapting them to Cold War Turkey. Although these magazines may have printed these comic strips for their entertainment qualities, they also exposed the children to American concepts and values prevalent in these comics such as capitalism, consumerism, and individualism (most notably in Disney comics). This article examines a large sample of children's magazines that were published during the 1950s, most of them (except for Doğan Kardeş and Çocuk Yuvası) weeklies: Acar (Brave); Armağan (Gift), Ateş (Fire); Ceylan (Gazelle); Cici-Mu (an abbreviation of “Sweet Muhamed,” as explained in the first issue); Çocuk Haftası (Children's Week); Çocuk Postası (Children's Post); Çocuk Yuvası (Nursery); Doğan Kardeş (Brother Doğan); Karınca (Ant); and Resimli Tomurcuk (Illustrated Bud).Footnote 9

Although Turkish children ages 5 to 14 constituted slightly less than a quarter of the population in the 1950s (23.5% in 1950, 23.3% in 1955), and although it is safe to assume that given their access to the Turkish education system they enjoyed a higher literacy rate than the general population (45.5% for men and 19.4% for women in 1950), only a handful of studies exist on what Turkish children were reading during the Cold War.Footnote 10 In this article I hope to contribute to the current literature on children in the Middle East and the cultural Cold War by examining the representation of the Cold War in Turkish children's magazines in the 1950s. To do so, I pose the following questions: How did these magazines introduce the Cold War to children? How did they construct the image of Turkey as part of the Western camp? Did they promote American values? How were the Soviets and communist states depicted in these magazines? Did these magazines leave any room for the children's agency, such as reader's letters or drawing competitions? Answers to these questions and others will allow us to better understand the impact of this global event on Turkey, a Middle Eastern Muslim country, contributing to expansion of study of the “cultural Cold War” beyond the United States and Europe, as well as to the study of children's history in the Middle East.

Although I was unsuccessful in pinning down the precise circulation of children's magazines in the 1950s, according to Erdoğan Bozok, who worked for Hamit Şendur's publishing house, one of the largest players in the field during the 1950s, children's magazines were privately owned, quite successful, and enjoyed high sales after the Second World War. Bozok adds that Şendur's publications for children in many cases constituted copyright infringements of American comics.Footnote 11 As we will see below, this tactic was not unique to Şendur. To understand the impact of the ideological dimension of the Cold War on Turkish magazines for children, I begin by describing the background of the Turkish experience of the early Cold War and the official view of communism in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Turkey in the Early Cold War

On March 19, 1945, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov informed the Turkish ambassador in Moscow, Selim Sarper, that the Soviet government had decided not to renew the Turkish–Soviet Friendship Treaty of 1925.Footnote 12 A few months later, on June 7, 1945, the Soviet Union stipulated that signing a new treaty would be possible under the following conditions: “joint” Turkish–Soviet defense of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus through the establishment of Soviet bases in Istanbul; the annexation of the eastern Turkish provinces of Kars and Ardahan (occupied by Russia in 1878 and repatriated in 1918); and the amendment of the Montreux Convention of 1936 to allow free passage of Soviet warships through the straits and their closure to non–Black Sea states.Footnote 13 As a result of this Soviet pressure, Turkey tried to tie itself to the West and succeeded in doing so with its participation in the Korean War and, as a result, its accession to NATO. During the 1950s, Turkey enjoyed American funding, guidance, and protection, and had strong political and cultural ties to the US.Footnote 14

The Communist Party in Turkey had been banned in 1925; its leaders were arrested and most of its remnants operated underground with no actual power or influence on the Turkish political sphere.Footnote 15 After the Second World War, Turkey's persecution of leftists and communist groups intensified. This persecution began in the last ruling period of the Republican People's Party (CHP), in the years 1944 to 1950, and reached its peak under the rule of the Democrat Party (DP), especially during the Korean War. Among the most prominent examples were the burning of the leftist Tan (Dawn) printing press in December 1945 by right-wing supporters, and the murder of Sabahattin Ali, a socialist novelist and poet, in 1948.Footnote 16 Another famous example was the firing of Pertev Naili Boratav, Behice Boran, and Niyazi Berkes, all of whom were left-wing professors from the Faculty of Languages, History, and Geography at Ankara University, and accused of disseminating communist propaganda.Footnote 17

According to Özdemir and Şendil, the increased pressure on the left under the rule of the DP was not only because of their perceived threat, but also part of Turkey's efforts to secure a place in the Western bloc by denoting leftist ideology as a major peril.Footnote 18 Öztan and Kaynak argue that during this period Turkey's desire to be a part of the West's fight against communism was visible on every level. It extended to the realm of economics, as demonstrated by the fact that at the Izmir International Fair in the 1950s and 1960s the exhibits of Eastern Bloc countries were inspected numerous times by the Izmir police on suspicion of promoting communist propaganda, but the US received favorable attention as it promoted new consumerist values and goods. The process of engaging in the capitalist system was reinforced by mechanization in agriculture, urbanization, and extending highways, as the DP's promise to turn Turkey into “Little America” started to manifest in the form of movies, advertisements, and consumer products. The spread of American comics, Hollywood movies, and American cuisine were the first signs of this cultural influence. According to Öztan and Kaynak, Turkish school children began to be indoctrinated with a national ethos and “love for America,” integrated with anticommunism.Footnote 19 Before we turn to the representation of the Cold War in Turkish children's magazines, a short introduction to their readership and contents is called for.

The Magazines’ Readership and Contents

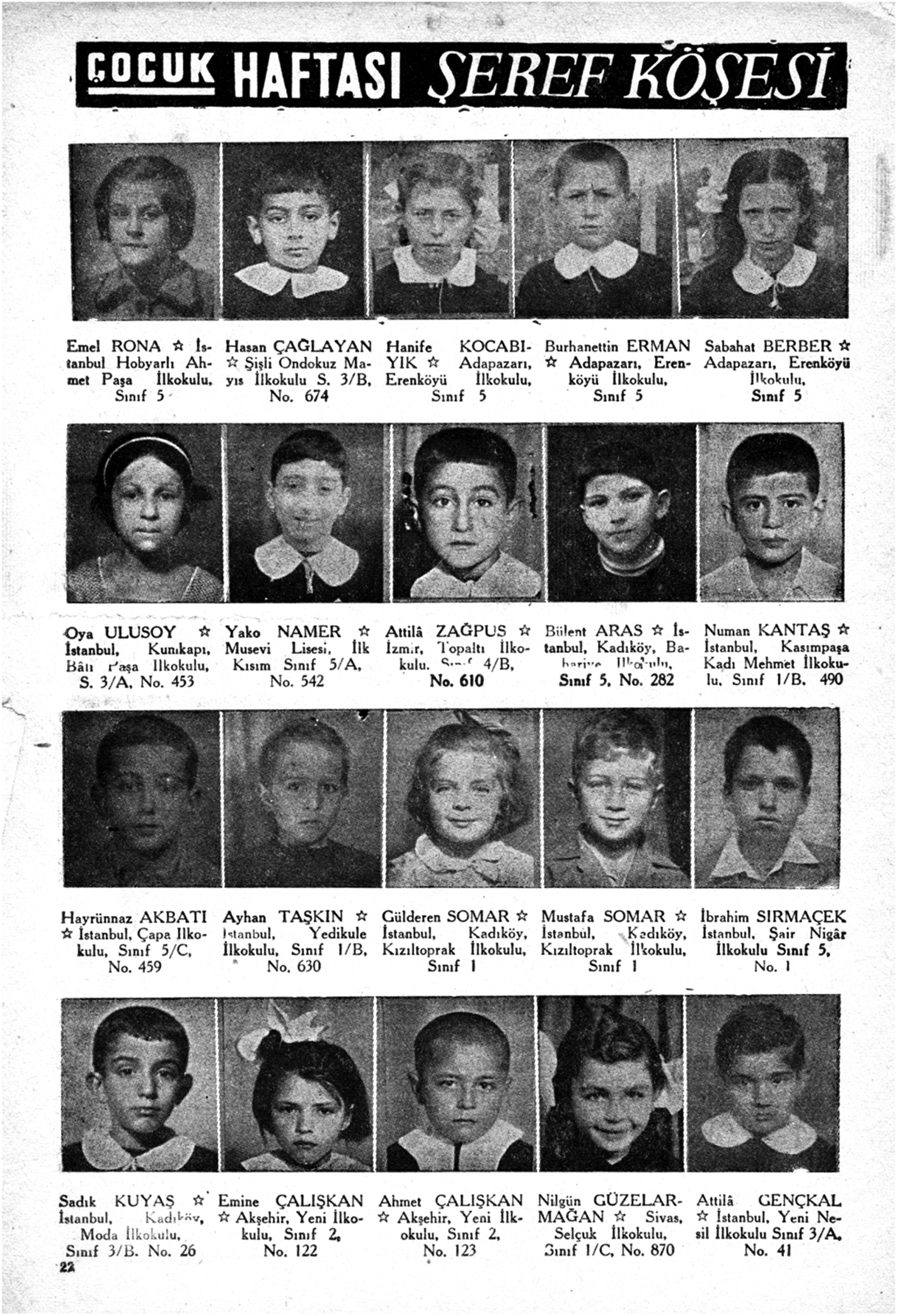

Some magazines, including Ceylan, Çocuk Haftası, Cici-Mu, and Çocuk Yuvası, invited their young readers to join their “club” (çocuk klübü) or “honorary corner” (şeref köşesi) by sending their photos to be published in future issues along with their names. Although the format was similar, the magazines differed in the details that accompanied the readers’ photos. Çocuk Haftası, for example, listed the children's names, grades (almost all of them elementary schoolchildren) and the cities (or neighborhoods) in which they lived. These honorary corners or clubs tell us quite a bit about the magazine's readership—first and foremost, that it included both boys and girls (Fig. 1). It is unclear whether these photographs reflected the ratio of boys and girls among the readers or if they were chosen specifically to showcase the magazine's diverse readership. The children's addresses suggest that the magazine was available in cities throughout Turkey, from Istanbul, Balıkesir, and Izmir in the west, to Ankara in the center, Adana in the east, and Sarıkamış and Erzurum in the south. However, we should remember that according to the census of 1950 only a quarter of the population lived in major urban centers, and we do not know whether or not these magazines reached rural areas.Footnote 20 These lists also tell us that the magazine was read by at least some minorities, as demonstrated by the photo of Yako Namer, a first-grade student at the Jewish school in Istanbul.Footnote 21 Other magazines were less detailed than Çocuk Haftası and included only the names and photos of the children.

Figure 1. Çocuk Haftası's honorary corner. Source: Çocuk Haftası, 27 August 1958.

Although most magazines did not publish reader's letters, Acar announced that since it received many letters from its readers it would answer them in a new column titled “Mailbox” (posta kutusu). In this column, the magazine usually published the name of the reader and their location, as well as the answer to their question. Although many of the letters addressed practical matters such as “where can I get previous issues of Acar” or revolved around the magazine's great lottery and prize (a bicycle), some readers asked if the magazine received the poems they had sent and whether they would be published or not. This column not only increased children's agency, but also encouraged them to show initiative. Çetin Tuna from Izmir, for example, asked whether he could serve as Acar's correspondent in Izmir. The editors promised him that if he sent small news items from Izmir that would be of interest to Acar's readers, they would publish them. They only requested that he write in a short, concise, and legible manner.Footnote 22 However, since the magazine lasted for only a few more issues, Çetin never got to publish anything.

During the Korean War, Acar informed its readers that the magazine would send a letter to Turkish soldiers fighting in Korea on behalf of Turkish children, “conveying their greetings and love to our Korean heroes,” and called upon children who wanted their names added to this letter to send their names and the names of their friends to the magazine. The magazine's editors promised to update the children upon receiving replies from Korea.Footnote 23

Slightly greater agency was given to children by the magazines Ceylan and Resimli Tomurcuk, which invited children to submit poems and drawings for publication. Ceylan even promised a lucrative payment of 1 lira for a poem or 2.5 lira for a story to those whose work was published (the price of one issue was 30 kuruş), giving the children an opportunity and a material incentive to use their unique voice and take a more active role in society.Footnote 24 Some of the children used this opportunity to show their support for the soldiers and the war: at least three poems titled “Korea” were published by Resimli Tomurcuk, as were other poems revolving around the war and Turkish heroism.Footnote 25 Although the magazine also invited its readers to send drawings, this invitation seems to have remained unanswered, maybe because of the magazine's requirement to use Indian ink.Footnote 26 Ceylan magazine faced a similar problem a few years later. When thanking a long list of children who sent their cartoons for publication, the magazine informed them that since their cartoons were made with pencil or regular paint, it was not possible to print them. It reminded the children that the drawing should be made on transparent tracing paper and using Indian ink. This may also speak to the socioeconomic status of the children whose works were published, given that these materials would need to be bought specially. The magazine also expressed its right to reject submissions, as we learn from its reply to Metin Tetik from Eskişehir. Although the editors expressed their enjoyment of the cartoon he sent, they wrote that they were waiting for him to send cartoons which were more “appropriate for the magazine,” leaving us and the original readers wondering about the content of his cartoon.Footnote 27

But what were these children reading? One of the most recurring themes in these magazines in the 1950s were locally produced historical adventure stories and comic strips promoting nationalism and patriotism.Footnote 28 These stories revolved around pre-Ottoman (pre-Islamic) Turkish heroes such as Oğuz Khan, the legendary father of the Turks, or Genghis Khan, as well as the adventures of heroic Ottoman sultans such as Mehmet the Conqueror (r. 1444–46, 1451–81) and Selim the Grim (r. 1512–20).Footnote 29 Of course, in many instances magazines were aware of their competition and published similar content. Stories and comics were not the only way to promote Turkish nationalism. Çocuk Haftası, for example, dedicated a regular column to Turkish geography, introducing the readers to one Turkish province each week. It also included a regular column on morals and religion (Ahlak ve Din), as well as one on Turkish proverbs (Atalarsözü).

In addition, the magazines published popular Western adventure stories and comics in translation. The latter included Mark Twain's Tom Sawyer, Detective (the sequel to the original Adventures of Tom Sawyer) and Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days.Footnote 30 They also included original stories inspired by foreign works, such as Peyami Safa's “Arsene Lupin in Istanbul: With and Against Cingöz Recai” (published under his pseudonym, Server Bedi); completely original pieces written by Turkish authors, such as “Children Heroes in Turkish History” or “Famous Turkish Victories”; and science fiction comics such as “Captain Lightning” (Yıldırım Kaptan).Footnote 31 Many of these magazines included an educational section with science articles, short encyclopedic entries on important people or past events, educational games, and crossword puzzles, probably not only for the children's enjoyment but also as a way to convince their parents to buy the magazine.

When considering how the Cold War was presented in these magazines, one should refrain from assuming that children and the cultural products intended for them simply mirrored the Cold War politics of adults, or that children readily assimilated the messages embedded in popular culture or government propaganda. As Grieve reminds us, each individual brings their own experiences and personal identity to reading books and playing games, including gender, class, race, and nationality. It is therefore difficult to generalize about how individual children interpreted the political content of cultural products. However, she adds, an examination of the era's juvenile pop culture can help us understand how adults conceptualized themes such as the nation's role in contemporary global politics during the Cold War years and the ways social reproduction worked through popular texts for children.Footnote 32

Atomic Spies: Fear of Espionage in the Early Cold War

One of the main characteristics of the Cold War era was the constant fear of “enemies within” (imaginary or real), such as spies and fifth columns. According to Peter Lee, from the 1940s onward, American creators catered to those fears by crafting espionage tales to simulate real life suspense and thrills.Footnote 33 These fears and their representation in comics and literature is also prevalent in contemporary Turkish children's magazines.

The first example of these themes appeared in the comic “Spies of the Atom!” mentioned at the beginning of this article. Set in London, it revolves around the attempts of Special Agent X from Scotland Yard and his assistant Dick Perry to retrieve the plans of the famous physicist Reginald Bradley for “weaponizing the atom” after their theft, during which Bradley is shot to death (Fig. 2). Based on intelligence that the killer might sail to New York, Agent X and Perry board the same ship. During their voyage they are able to arrest one of the spies, but the killer escapes. Upon arrival in the US, Agent X tracks down the spies but is apprehended by them, only to be rescued by his assistant. At the end of the comic, the heroes are able to retrieve the suitcase containing the plans and the spies (referred to as “gangsters” in the last installment) are apprehended by the police after the death of their leader. The ending leaves many questions unanswered: Who were these spies and why did they steal the plans? Were they planning to transfer them to an enemy state or sell them to the highest bidder? Why are they referred to as gangsters instead of spies? According to Ferenc Szasz, in the early 1950s several American comics borrowed characters and plots wholesale from the world of popular pulp fiction and added an atomic element to them, such as stolen plutonium or atomic plans, to turn them into a new “atomic comic” genre.Footnote 34 This seems to be the case here. The plot itself is very similar to a crime comic in which a suitcase is being stolen, only in this case, the readers are told that it holds nuclear secrets, giving the story a new dimension of urgency.

Figure 2. “Spies of the Atom!” part 2. Source: Çocuk Postası, 6 November 1950.

Although I have been unable to find the original comic, it is clear that it is not Turkish in origin: the heroes are foreigners, the story begins in London, and Special Agent X serves Scotland Yard. Either this is a British comic translated into Turkish, or it was originally an older crime-oriented comic repurposed by the publishers, who rewrote the dialogue to connect it to the Cold War, as the crude artwork and minimalist detail suggests. As we will see, repurposing older comics was not uncommon.

Espionage and atomic secrets also were the focal point of “Spies of the Atom” (Atom Casusları), an original story by the journalist, author, and translator Ali Avni Öneş, published in twenty-four installments in Armağan between 28 November 1951 and 7 May 1952. This story tells the tale of Orhan Yılmaz, a Turkish journalist who hears on the radio that his friend, the famous Turkish physics professor Mehmet Çetiner, and his plane have gone missing en route to Istanbul. Orhan suspects foul play and quickly realizes that other nuclear scientists around the world have also disappeared. He then goes to meet the professor's wife and expresses his suspicions, only to barely survive being pushed out of the ferry and into the sea by a “Chinese man with slanted eyes, yellow skin and high cheekbones.” The incident convinces him that someone is spying on the professor's house, planning to steal secret plans and formulas from his study. With the help of his friends and the professor's young, bright, and beautiful daughter, Suna, he tries to uncover the mystery and apprehend the spies. The group suspects that the newly arrived gardener and maid are a part of this spy organization (which turns out to be at least partly true), and after the professor's plans are stolen from his study, they are able to track down the spies’ cell and retrieve the documents with the help of the Istanbul police. At the end of the story, it turns out that the professor's kidnappers were a part of an international organization hiding in Africa trying to assemble nuclear weapons to control the world, and the professor is freed.Footnote 35

The prevalence of foreign elements linked to the espionage network (a Syrian gardener, a Greek maid, and an unidentified Chinese man) seem designed to spread anxiety among young readers.Footnote 36 The professor is described as someone who is well versed in “the secrets of atomic and hydrogen bombs and many other secret weapons,” but he prefers to highlight the peaceful potential of the atom: “If this mighty power is used for the sake of peace and for the good of humanity, a period of bliss will begin in the world.”Footnote 37 His daughter Suna serves as a role model for young female readers. She is described as an only child, 18 or 19 years old, an athletic girl with blonde hair and hazel eyes. But she is not only good looking; she is a quick learner, resourceful and brave, and also well educated (since she is in her final year at the American college). Her only desire is “to grow up as a knowledgeable Turkish woman and to help her father in all his studies.”Footnote 38

According to Szasz, American comic book editors could stretch the theft of atomic secrets only so far. By late 1951, American magazines had begun to deemphasize nuclear spying in favor of a basic war format, and the conflict in Korea had “moved comic book espionage cases to a new level: plans for guided missiles, secret formulas to destroy metal ships, and even biological warfare. Yet, these stories somehow lacked the intense drama associated with the search for atomic spies.”Footnote 39 Such comics were also published by Turkish children's magazines during the 1950s, for example, Abdurrahman Koçer's “Rocket Spies” (Roket Casusları) published in Cici-Mu between April and May 1955. This comic strip introduced a conspiracy in which Metin, the 14-year-old son of a Turkish rocket scientist, is kidnapped by a criminal organization to make his father hand over his plans for a new rocket so that they can be sold to foreign states. Later in the comic, Metin is rescued by a former member of the organization, who opposed the selling of state secrets to foreign powers because it would endanger the Turkish state. Although he manages to free Metin, he is captured and executed, but with his dying breath asserts, “I am dying, but I am not a traitor to the state!” (Ölüyorum! Fakat vatan haini değilim).Footnote 40

Turkish Soldiers Never Die: The Korean War in Children's Magazines

One of the recurring themes in children's magazines throughout the 1950s revolved around Turkey's participation in the Korean War, and especially the battle of Kunu-ri between 26 November and 30 November 1950, in which a Turkish brigade engaged the Chinese, who had overwhelmed the American forces with a surprise attack. The brigade was successful in enabling American forces to retreat while suffering heavy losses, which earned it praise in both local and international media. It was later awarded the American Silver Star medal for its actions.Footnote 41

On 21 March 1952, the Turkish children's magazine Acar published an article titled “The Turkish Bayonet in Korea,” which focused on the heroism of the Turkish soldiers fighting alongside Western allies, emphasizing their heroism. Reporting that many had been badly injured, the article noted that “they had only one wish: to get well soon, to return to Korea as soon as possible to avenge the death of their friends.” The article not only stressed the soldiers’ heroism but also their reluctance to brag about the battle. It gave the example of a Turkish soldier named Ömer from Ankara, who might have amazed everyone if he had shared his story, but “no matter how hard they tried to get him to tell it, it was all in vain, he always closed the topic by saying: ‘we fought . . . what is there to tell?’” The author did tell the readers how Ömer and his fellow soldiers put their bayonets on and charged a larger Chinese force that encircled them, breaking free while shouting “Allah . . . Allah.” After the unit had regathered Ömer was nowhere to be seen and was assumed dead, until he showed up the next morning, badly injured, carrying his wounded officer.Footnote 42 From Ömer's example, young readers learned how true heroes should behave.

Children's magazines continued to write about the war during the subsequent years. Cici-Mu, for example, dedicated its eighth issue, published on 12 March 1955, to the Korean War (Fig. 3). This issue included the first installment of an illustrated story titled “The Turks in Korea,” which was published between 12 March and 28 April. The story told of a group of soldiers who were retreating from battle. Although there was no explicit mention of Kunu-ri, it appears that this story was inspired by the events of that battle. The story described how a part of the group was taken captive by the Chinese and was rescued by their friends. In this story too, the religiosity of the soldiers (who prayed more than once during the very short story or referred to Allah's help in battle) was depicted.Footnote 43 The story also conveyed nationalist messages, since one of the soldiers says that “it is easier for me, for us, to die than to become a POW, more honorable.”Footnote 44 The fact that they fell captive was explained by the fact that Chinese forces were five to ten times larger. Chinese soldiers even acknowledged the Turks’ fighting spirit, mentioning that “they do not accept defeat.”Footnote 45

Figure 3. “The Turkish Soldier in Korea.” Cover photograph. Source: Cici-Mu, 12 March 1955.

Between May 28 and August 6, 1958, shortly after its renewed publication after a gap of eight years, Çocuk Haftası published an eleven-installment comic strip titled “The Hero Lieutenant” (Kahraman Teğmen). The story, set in Korea in 1951, tells the story of Metin, a Turkish lieutenant tasked with destroying a North Korean radar station and airplane hangar. Metin is given command of twenty soldiers, all of them volunteers. They parachute behind enemy lines, and although they are able to complete their mission without casualties their plane is destroyed, and they are left stranded in North Korean territory. The force is, however, able to contact their headquarters, free the lieutenant's aide who fell captive, and breach the North Korean encirclement, with the lieutenant running toward the Korean forces and throwing hand grenades, wreaking havoc among them. The comic strip ends with the soldiers back in their headquarters and their commander telling Metin that he deserves a medal, only to hear the expected overpatriotic reply: “We just did our duty!” (Biz sadece vazifemizi yaptık!).Footnote 46

Although I have not been able to find the original, it is clear that this Turkish comic is the adaptation of an American comic from the Second World War, given that it contains remnants from the original. For example, in the first installment, when the general shows the location of enemy forces on the map, these are represented by Japanese flags. In another scene, in the seventh installment, a Japanese flag again appears in the “North Korean” camp (Fig. 4, third panel).Footnote 47 The animation style is also very different from other comic strips and cartoons published by this magazine, being more detailed and mature. In addition, the most prominent symbol of the Turkish soldiers in Korea, the bayonet, is conspicuously missing from the comic.

Figure 4. “The Hero Lieutenant.” Source: Çocuk Haftası, 9 July 1958.

The Turks are depicted in this strip as smarter and stronger than their enemies. One example of this is when a North Korean soldier tries to infiltrate their post wearing the uniform of the lieutenant's captive aide. Although he is sure he is going to outsmart the Turkish soldiers, he fails to give the password to the question, “Who won in the [football] match between Fenerbahce and Galatasaray?” and is shot by the Turks. This soldier is also drawn in a way that expresses racist stereotypes against the “Yellow Peril,” such as the slanting eyes and long nails that were common in contemporary American comics, so exposing Turkish readers to them.Footnote 48 One of the most interesting aspects of this particular strip is the fact that the Turkish forces were depicted as fighting North Koreans, who were hardly mentioned in literature, cartoons, movies, or memoirs about the war, rather than the Chinese, which would have been more historically accurate.Footnote 49

Since the representation of the Korean War focused on the heroism, masculinity, and religiosity of the Turkish soldiers, ignoring most of the other participants in the war, these references did not change during the 1950s. As will be demonstrated in the next section, even the representation of the Americans did not undergo significant change in these magazines during the 1950s, which kept mirroring the official positive state discourse toward them, in times of growing anti-Americanism.

Introducing the Cold War to Children

In the early 1950s, the Turkish dream of becoming like America was also present in children's magazines. In its first issue, in September 1952, Ateş, for example, published an advertisement titled “You Can Become an American Movie Star Millionaire!” The ad informed children that an American film company was looking for a Turkish child to cast in its next project, and that the child would be selected from among the magazine's readers. Potential applicants should subscribe to the magazine, be under the age of 18, and be enrolled in school. In addition, applicants should send their photograph and win a talent show and “brain games” competition organized by the magazine. According to the ad, the winners of these competitions would be given a role in a movie to be shot in Turkey, and those who succeeded in this film would be sent to America.Footnote 50 Although the advertisement appeared in several issues, it is unclear whether any of the magazine's promises, unlikely real, were ever fulfilled. In any case, the positive atmosphere of the early 1950s did not last long.

According to Güney, Türkmen, and others, anti-Americanism in Turkey started in the 1960s as a result of the withdrawal of Jupiter missiles from Turkey in the 1962–63 aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis, and continued with President Lyndon Johnson's refusal to support Turkey in Cyprus in 1964 and a subsequent arms embargo on Turkey.Footnote 51 Others accused the US of cultural imperialism, arguing that Turkey had not become an equal partner or ally of the US, but was downgraded to the level of a colony.Footnote 52 However, according to Tuba Ünlü Bilgiç, although anti-Americanism can be traced back to the late 1940s, it intensified during the late 1950s after a series of incidents between American soldiers and the locals. This led to America being characterized by the media as a “rude,” “vulgar,” “uncivilized,” “presumptuous,” and “arrogant” nation.Footnote 53

Children's magazines, however, continued to depict the Americans positively, by focusing on topics such as the UN, the Turkish-American friendship, and the (still rather new) atomic world, while also presenting young American girls visiting Turkey as positive role models for Turkish children. One example is an article published in Çocuk Haftası in October 1958, titled “A RADAR was built to protect us from the ATOM.” According to this pseudoscientific piece, the atomic bomb experiments, which were created in preparation for the great wars of the future, held great potential for humanity and included the prospect of nuclear vehicles and even atomic hearts that would prolong human life, but also possessed the danger of radioactive rays and impacting the changing of the seasons. According to the article, everyone knew the terrible destruction caused by wars, and today “no civilized person likes or wants war anymore. When wars disappear in the future, these [nuclear] bombs will no longer be needed, and scientists will spend their efforts and energy for the welfare of humanity.” The article did point out that many people “died horribly” from radiation in Hiroshima, yet it tried to dispel any fears the readers might have by explaining that “our American friends have succeeded in building an enormous radar . . . [whose] task is . . . to collect all these harmful [radioactive] substances from the air and render it harmless.”Footnote 54

Some magazines referred to global alliances, and especially the UN. Çocuk Haftası's cover story on October 22, 1958 celebrated “United Nations Day.” The cover of this issue showed a group of boys and girls holding the Turkish flag under a huge symbol of the UN (Fig. 5).Footnote 55 The article's subtitle set the positive tone for the rest of its content, by stating that the day on which the UN was established was an important day that should be celebrated: “The United Nations organization was established in 1945 for the very high ideal of realizing the cause of peace in the world. October 24 is celebrated every year in all free nations as the day of this organization.” By stating that “all free nations” celebrated this day, the author indicated to readers that since Turkey was one of those states, they also should celebrate it.Footnote 56

Figure 5. “In this issue: United Nation's Day.” Source: Çocuk Haftası, 22 October 1958.

Another example appeared in an article titled “Your American Friend” as part of the regular column “Your Teacher Says . . .” in Çocuk Haftası in January 1959.Footnote 57 The article introduced the readers to an American girl named Heidi, who goes to school in Izmir because her father is a staff sergeant at NATO headquarters. After informing the readers that “Heidi Lee Miller is your friend,” the author, a teacher named Sadik Övet, notes that “to understand why this American family is in our country,” one needs first to understand terms such as the United Nations, UNESCO, and NATO; the author proceeds to explain them. The article introduces the UN as follows:

At the end of the Second World War, the Americans established the United Nations with the idea of saving the world from the dangers of war. When the war ended, 51 states, large and small, joined this institution. . . . We are a prominent member of this institution [emphasis mine]. If a nation does not abide by this agreement, if one of the United Nations members is under attack, the others immediately unite and come to the aid of the attacked state. The best example of this is the Korean War. As you know, we kept our promise by showing heroism there.Footnote 58

Perhaps the most important focus in the article is given to NATO, described by the author as “a community that deals with the military affairs of its members,” explaining that the need for such an organization was caused by “Soviet Russia [who] tried to force the peoples of the places it entered in the Second World War to accept its form of state.” The author then thanks Heidi's parents, saying that “they know humanity and understand friendship,” and that he wished he could go to Izmir to thank them personally and assure them that Heidi's teachers would take good care of her.

In another article, published later that year, the same author describes a meeting with a friend who hosted an American exchange student. After Övet asks trivial questions about the way Turkish customs are viewed by the American guest (whose voice is absent in the article), he explains the logic behind the program. According to his friend, mature, serious, dignified students capable of leadership are picked for this program so that they would be better suited to “serve humanity” in the future. The author also describes how he invited two of his former students, who were passing by, to meet the girl, but upon hearing that she was an American, they both “frowned, and walked away.” He then remembered that the two, who studied in foreign schools, were treated badly by their administration, and speculated that they held a grudge against all Americans because of that. The article ends with the author wondering about the impact an exchange program might have had on these two boys if they were to be sent to the US and met the good people there.Footnote 59

A month later, in September 1959, Doğan Kardeş published a similar story, titled “A Lesson Taught by an American Girl.” The article introduced the readers to another American girl who arrived in Istanbul as part of an exchange program (probably the same program mentioned above) and described her as a polite and gentle girl who helped around the house and, according to her host family, also had a positive influence on their children. When asked about it, the American girl replied that in the United States children help around the house even in the richest families, which also allowed them to earn some pocket money.Footnote 60

The rare personal encounter aside, it was much easier to “run into” Americans in American cartoons. Some of the most common comic strips published in Turkish children's magazines were the seemingly innocent strips produced by Disney, with famous heroes such as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Pluto, Goofy, and others. Although Disney comics were first published in Turkish children's magazines in the 1930s, they became more popular in the 1950s and were published by several magazines. As Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart argue in their seminal work, How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic, Disney comics are “full of Americanisms, in custom and language” and “are replete with the ‘social differences’ between rich and penniless (Scrooge and Donald), between virtuous ducks and unshaven thieves; political ideas frequently come to the fore; and, of course, natives are often characterized as dumb, ugly, inferior and criminal.”Footnote 61 In the next section, I discuss how these American concepts and values were instilled in Turkish children through translated Disney comic strips, although these strips also included elements adapted for the Turkish audience.

American Values and Concepts in Disney Comics

One of the best examples of Disney comics “translated” into Turkish is a Donald Duck adventure, “VakVaka Buzlar Ülkesinde,” published in Resimli Tomurcuk between October 29, 1952 and May 20, 1953.Footnote 62 Originally published in English in December 1949 under the title “Luck of the North,” this comic tells the tale of how Donald Duck, sick of his cousin Gladstone bragging about his luck, winning every possible lottery and finding money in unlikely places, tries to trick him into leaving the city for a while, sending a phony map to a “lost uranium mine” his way. When Donald realizes that the coordinates that he wrote on the fake map are in the middle of an Arctic wasteland, though, he begins to have second thoughts about putting Gladstone in such peril and decides to go to the polar regions with his nephews, Huey, Dewey, and Louie, to save Gladstone and bring him back home. In the end, the ducks find Gladstone, as well as an ancient Viking ship containing a golden treasure. Gladstone declares ownership of the ship's cargo and abandons the ducks to their fate on board the Viking ship. They then use it to sail home, depressed and barely surviving the weather, only to realize that an old map they found on the ship is actually priceless and is worth more than all the gold taken by Gladstone.Footnote 63

According to Kenan Koçak, when Tintin appeared in Turkish children's weeklies it was adapted to Turkish culture.Footnote 64 Similarly, there are several major differences between the original “Luck of the North,” and the Turkish “VakVaka Buzlar Ülkesinde.” First, the original was published in color, whereas the Turkish adaptation is traced in black and white. In addition, the Turkish version skips the first two installments of the English version, in which Gladstone shows off his luck and rubs it in Donald's face. Another major difference is that both Donald and Gladstone are called VakVaka, which makes the comic more difficult to understand. The Turkish animators also tried to make the story a little more familiar to the readers. One such example occurs when Gladstone is leaving for Alaska. He boards the plane from Yeşilköy airport in Istanbul (the original version did not include a specific location). One of the most interesting interactions in the comic takes place between the ducks (first, Gladstone, and later Donald and the nephews) and the Inuit (Eskimos in the original). According to Dorfman and Mattelart, indigenous and native populations are usually depicted in a stereotypical manner as primitive, residing in backward dwellings such as huts (or in this example, igloos), and wearing their traditional clothes. Moreover, they are depicted like children; they speak the same language as the heroes (but in many cases using very basic expressions and faulty grammar), they are friendly, carefree, naive, trusting, and happy, but it is never easy to deceive them.

As Dorfman and Mattelart note, Disney comics represent American imperialism as harmless; natives are usually willing to give up everything material (including treasures that are just sitting around waiting for Western people to take) in exchange for trinkets and useless items.Footnote 65 In this comic, Gladstone uses his great luck to summon a whale using what he misleads the natives to think is a magical horseshoe, in exchange for the Inuit's main source of livelihood, their two kayaks used for hunting whales. He then leaves in one kayak, destroying the other to prevent anyone from following him.Footnote 66 In the original English version the Inuit speak a very basic English using faulty grammar; for example, when Gladstone asks if they use their boats for hunting, the local chief replies: “Yes! Need Kayak plenty! They no for sale!” However, in the Turkish version, it seems that the translator “corrected” their original faulty expressions, and their Turkish does not convey the same message of backwardness as the original.

Donald and his nephews also promoted capitalism and consumerism in other children's magazines as well, such as Karınca, in which the nephews, who have prepared a long list of hoped-for presents for the holiday (including, of course, a subscription for Karınca), are told by Donald that their list “should not exceed the size of a postage stamp.” Huey, Dewey, and Louie then outsmart their uncle by writing their list in tiny letters and using a projector to show it to Donald.Footnote 67 The magazine's cover, unrelated to this comic, also promoted capitalism by presenting Donald standing in front of a mirror, imagining himself to be a rich duck (Fig. 6).Footnote 68

Figure 6. Donald Duck imagines being rich. Source: Karınca, 3 May 1952.

A classic example of the dissemination of American values and concepts in Disney comics is demonstrated by a short comic published in Ateş magazine in March 1953. This comic starts by showing Mickey Mouse reading Goofy the morning newspapers, according to which Goofy is one of the ten worst dressers in the city (it does not say which city). When Mickey criticizes the poor state of Goofy's clothes, the latter replies “What about it? I have lived with these clothes for years like a close friend!” The shocked Mickey then decides to take Goofy to a tailor to buy some new clothes. After the tailor promises to bring Goofy new clothes made especially for him (which he delivers immediately), Goofy agrees to try them on. Upon seeing his reflection in three mirrors in the store and mistakenly thinking they are other people, he accuses the tailor of trying to cheat him because “he had already seen three other people wearing the same ‘special’ outfit.” The annoyed Goofy throws the clothes at the surprised tailor and storms out, where he complains to Mickey (Fig. 7).Footnote 69

Figure 7. “Mickey and Goofy Buying Clothes.” Source: Ateş, 25 March 1953.

Although this short comic might be viewed as harmless and amusing, making fun at Goofy's expense, one should also remember that Disney comics “could be read on multiple levels, appealing both to children and adults.”Footnote 70 This comic seems to promote American capitalist values and concepts while spoofing them at the same time, depending on the reader's perspective. The starting point is the fact that Goofy is being judged (we do not know by whom) for his appearance. Mickey's immediate response is to go and buy new clothes, demonstrating one of the main tenets of capitalism, consumerism. This should not come as a surprise; Dorfman and Mattelart have already pointed out that “in the world of Disney . . . [t]here is a constant round of buying, selling and consuming, but to all appearances, none of the products involved has required any effort whatsoever to make.”Footnote 71 This also is true here. The tailor promises Goofy clothes made especially for him, and then appears with everything made, without even taking Goofy's measurements. Goofy's anger at the tailor for seeing “three other people wearing the same ‘special’ outfit” might be taken at face value, especially by younger readers, legitimizing another American value, individualism, expressed by the importance Goofy gives to buying specially made clothes. One should note that although the comic is making fun of Goofy, it does so by laughing at the fact that he mistook his reflection for other people, not by ridiculing or criticizing his desire for unique clothes. However, older readers may understand the same comic as criticizing, or at least making fun of, the value of individualism, because Goofy, who usually plays the role of the village idiot in Disney, is the one promoting it.

Conclusion

Turkish children's magazines in the 1950s not only supported and promoted Turkish nationalism but also played an important role in exposing children to the new Cold War realities, introducing a positive view of the US and supporting Turkey's Western stance during the early years of the Cold War. Original Turkish content was based mainly on stories and comics that reflected common anxieties typical of the Cold War, such as fear of espionage and fifth columns, also focusing on the Turkish heroism in the Korean War, instilling children with patriotism and militarism. Turkish content also stressed the importance of international organizations in which Turkey was a member, such as the UN and NATO. Surprisingly, there were hardly any references to the Soviet Union or the “Red Menace” as the enemy. Foreign comics translated into Turkish reproduced American concepts, such as racism against Asians, which coincided with China's role as the enemy in the Korean War.Footnote 72 During the Korean War, several American comics criticized politicians and the government for not supporting the troops enough and not supplying them with the means to win the war. The soldiers themselves were not invincible and were often described as frustrated, suffering the hardships of war, and even hurt in battle or killed. American soldiers were even depicted losing battles in Korea.Footnote 73 However, these kinds of comics were not translated into Turkish. It appears that Turkish publishers were happy enough to reprint a more naive version of the war for the public, a version that viewed the war as a just one, with a clear distinction between good and evil, in which victory was achieved easily and heroically. One also should remember the threat of censorship hanging over the heads of Turkish publishers, which may explain their reluctance to print translations of controversial American comics. According to Çağrı Erhan, in August 1950 seventeen satirical magazines in Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir were closed down because they published articles and cartoons that were critical of troop deployment in Korea.Footnote 74

Although most Turkish children's magazines published during the 1950s referred to the Cold War, there were some who ignored it. Yavrutürk (1957–58), for example, addressed a very young audience and printed apolitical contents suitable for its readers, such as animal cartoons with very short texts (or no text at all), stories and comics introducing ancient Turkish history, and pictures and games for children to draw and play.Footnote 75 Others, like Doğan Kardeş, tried to promote more liberal political views, highlighting internationalism, or nonviolence as demonstrated by India, with Gandhi as a possible role model.Footnote 76 However, even Doğan Kardeş used the United States as an example of progress, supporting the positive view of America.Footnote 77

Turkish children in the 1950s were told in many ways, either at school or in their favorite magazines, that they were a part of the Western camp and close allies of the United States. However, a series of events in the 1960s put that to the test. Growing political and economic instability in Turkey ended in the 1960 military coup. The Democrat Party that had ruled for a decade was abolished, some of its leading figures were hanged, and others found themselves in jail; a new, more lenient constitution was put in place.Footnote 78 How this new liberal constitution and the rise of anti-Americanism impacted Turkish magazines in the 1960s remains to be seen.

Appendix: Publication Details of Magazines Discussed in This Article

1. Acar (Brave). Editor and owner: Faruk Riza Güloğul. Istanbul: Anıl Matbaası (1952).

2. Armağan (Gift). Editors: İlhan Gürsoy (1950–51), M. Turhan Şimga (1951–57); owner: Hamit Şendur. Istanbul: Çocuk Yayınları Kollektif Şirketi Matbaası (1950–57).

3. Ateş (Fire). Editor: Nazim Ünverdi; owner: Hamit Şendur. Istanbul: Çocuk Yayınları Müessesesi (1952–53).

4. Ceylan (Gazelle). Editor: Erdoğan Egeli; owners: Erdoğan Egeli and İsmet Tekdal. Istanbul: Dizerkonca Matbaası (1955–56, 1966).

5. Cici-Mu. Editor and owner: Mehmet Cemil Dağlaroğlu. Istanbul: Rıza Koşkun Matbaası (1955).

6. Çocuk Haftası (Children's Week). Editor and owner: Celal Demiray. Istanbul: Türkiye Basımevi (1958–64).

7. Çocuk Postası (Children's Post). Editor: Orhan Yüksel; owners: Orhan Yüksel and Arman Atuf Kansu. Istanbul: Tan Matbaası (1950–51).

8. Çocuk Yuvası (Nursery). Editor: Çocuk Yayınları Müessesesi. Istanbul: Çocuk Yayınları Müessesesi Matbaası (1954–58; 1962–75).

9. Doğan Kardeş (Brother Doğan). Editor: Vedat Nedim Tör. Istanbul: Doğan Kardeş Yayınları A.Ş Basımevi (1945–78).

10. Karınca (Ant). Editor: Ramazan Gökalp Arkın. Istanbul: Osmanbey Matbaası (1952–53).

11. Resimli Tomurcuk (Illustrated Bud). Editor: M. Turhan Şimga; owner: Hamit Şendur. Istanbul: Çocuk Yayınları Müessesesi Matbaası (1952–54).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Umut Uzer and Fruma Zachs for their helpful comments and remarks at the various stages of this article. I also am grateful to the editor and the anonymous reviewers at IJMES for their helpful critiques, insights, and suggestions.