Introduction

Traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine (TCIM) has demonstrated its unique advantages and values in improving people’s health, and 170 of 194 (88 percent) WHO member states have admitted the formal use of TCIM within their health systems in an investigation (1;2). TCIM is an integrated conception, encompassing three parts: “traditional” therapy is viewed as a total sum of historical knowledge and beliefs unique to different ethnic groups, “complementary” therapy is defined as a non-mainstream practice used together with conventional medicine, while an “integrative” therapy is a combination of complementary approaches used in conjunction with conventional medicine (Reference Ng, Hilal and Maini3). Among these, acupuncture has witnessed thriving and prosperous worldwide, though this technique was originally a feature of traditional Chinese medicine. According to the WHO’s survey including 129 countries, 80 percent of them recognized the use of acupuncture, with 18 countries reimbursing acupuncture in their healthcare service system (1).

To promote the high-quality development of TCIM, plenty of policies touching on clinical efficacy evaluation and value-based HTA have been introduced in China. Those evaluation systems are designed to showcase the theories, features, and value of TCIM, and eventually to inform the reimbursement decision-making and pricing of TCIM services (4). Furthermore, the value assessment framework for Chinese patent medicine has been issued by an academic institution. Whereas, there is no value framework for non-pharmacological therapies up to now. Therefore, Chinese healthcare decision-makers are pretty eager to use such tools to support their policy adjustment.

Apparently, to galvanize the reviving of TCIM, it is imperative to incorporate more traditional medicine services into health insurance coverage based on the high-quality value evaluation evidence (Reference Kwon, Kim and Kim5). Consequently, It is necessary and valuable to conduct a scoping review of HTA practice in TCIM to have a general understanding of the evaluation dimensions and challenges. Given the wide adoption of acupuncture, the HTA reports of acupuncture can be more easily accessible than those of other traditional non-pharmacological therapies. It can bring more practical insights to develop the value assessment framework of traditional non-pharmacological technology by reviewing and synthesizing value domains and weaknesses mentioned in HTA reports of acupuncture treated for various diseases. We hope that the value framework can conduce to elucidate the potential value of traditional non-pharmacological therapies for disease prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, and inform healthcare management and reimbursement policy-making in China.

Methods

Study Design and Search Strategy

To outline the evaluation framework of TCIM informing the value assessment and reimbursement decision making, a scoping review of the HTA guidelines for TCIM and HTA reports for acupuncture was conducted, complying with the methodological framework introduced by Arksey and O’Malley and refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares6–Reference Arksey and O’Malley8).

The PRISMA-ScR was adopted to elaborate this study and the PRISMA-ScR checklist can be found in Supplement 1. HTA, traditional medicine, complementary medicine, acupuncture, and other similar terms were used as keywords to construct the search strategy, retrieving the published literature on HTA in TCIM from relevant electronic databases, such as Medline (PUBMED), EMBASE, Web of Science, the International HTA database hosted by INAHTA, CNKI, Wanfang, and HTA agencies, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Agency for Care Effectiveness (ACE), the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC), the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) from inception to January 2023. The full search strategy can be found in Supplement 2. The scoping review protocol was not registered in a registry.

Study Selection

Given the purpose was to pay attention to the HTA domains of TCIM and the HTA differences between TCIM and modern medical products, studies focusing on guidelines or standards specific to TCIM were included. In consideration of scarce assessment guidelines of TCIM, HTA reports of acupuncture for any diseases in the context of HTA organizations or agencies or other bodies worldwide were included as well, used to summarize HTA domains and characteristics of TCIM. HTA reports written in Chinese or English and available full texts were included. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The preliminary screening by titles and abstracts as well as the final screening by full texts was performed by two independent researchers (D.D. Ai and C.A.X. Duan) to determine the eventually included literature and potential disagreements were solved by a third author (B.Y. Sui).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data Extraction

A predefined qualitative data form encompassing report characteristics, HTA agency, country, year of publication, HTA domains, population, intervention and comparator, results, limitations, and implications were used to extract key information by two independent researchers.

Data Synthesis

A descriptive analysis and a narrative synthesis were performed employing tables to synthesize the HTA domains and the main characteristics of each report.

Results

Reports Selection

Overall, of the 993 records retrieved after deduplication, 971 were screened out since they were studies without acupuncture as an intervention, studies focusing on a narrative review of HTA in traditional medicine, or no guideline or consensus. Finally, 5 guideline or consensus records from China (Reference Yuan, Zhang and Liu9–13) and 17 acupuncture HTA reports from international HTA agencies (14–30) were included in the review. The full selection process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Description of Included Studies

Outline of HTA Guidelines or Consensus in TCIM

Five guidelines or consensus records (Reference Yuan, Zhang and Liu9–13) about value assessment of Chinese patent medicine released by Chinese academic groups were identified, while there were no published HTA guidelines or consensus for TCIM in other countries and regions. In 2021, the China National Health Commission (NHC) issued the Management Guideline for the Clinical Comprehensive Evaluation of Drugs, which involved six domains, including safety, effectiveness, economy, innovation, suitability, accessibility, to measure the value of a drug based on the HTA methods and multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) to improve clinical rational use of medicines (31). Since then, China healthcare sectors and academic groups have been promoting clinical comprehensive evaluation of drugs. With that management guideline, in the field of TCIM, the Chinese Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences and other institutions drafted or promulgated technical evaluation guidelines or technical specifications, and carried out clinical comprehensive evaluation of specific Chinese patent medicines, of which the evaluation dimensions were basically consistent with management guidelines issued by NHC (Reference Yuan, Zhang and Liu9–13). Notably, some institutions added up Chinese medicine-specific indicators, such as the traditional Chinese medicine theory, human use experiences, and so on (Reference Zhang, Wang and Xie11;Reference Zhang, Wang and Xie12). In another technical guideline developed by the Institute of Clinical Basic Medical Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, the three dimensions, namely safety, effectiveness, and economy, were drawn up from the national clinical comprehensive evaluation, and the other dimensions (application, science and standards) reflecting the features of TCM were proposed by Delphi method (see Table 2) (Reference Zhang, Liang and Chen10;13).

Table 2. Information table for comprehensive evaluation of Chinese patent medicine

Internationally, even though some HTA of TCIM were conducted to provide evidence for medical insurance coverage decision-making, there was currently no published value assessment framework or economic evaluation method aimed at traditional medicine or non-pharmacological therapies in other countries and regions. South Korea, Switzerland, Singapore, and the United Kingdom have attempted to apply HTA for traditional and complemental medicine to inform medical insurance reimbursement. In Korea, Hanbang services have been covered in the benefits schedule in the country’s National Health Insurance (NHI) since 1987. Currently, health insurance benefits of Hanbang are especially focused on treatments such as acupuncture, moxibustion, and cupping, while herbal medicines coverage is relatively rare. To promote Hanbang, it is necessary to prioritize the extension of health benefits to herbal medicines and traditional techniques with a lower rate of coverage. Consequently, the National Development Institute of Korean Medicine (NIKOM) has developed a strategic plan that includes the development of economic valuation guidelines specific to Hanbang services under the current HTA system. In line with the evidence-based decision making and value purchase principles, the government led the formulation of Hanbang clinical practice guidelines for services, the first batch of which contained 27 diseases (Reference Kwon, Kim and Kim5). In Switzerland, reimbursement for traditional and complemental medicine after 2017 will depend on the results of the evaluation projects and international HTAs (2). A systematic review of technical assessments of traditional medicine conducted by HiTAP, which included peer-reviewed articles, grey literature, and regional or international guidelines on the evaluation of herbal products and traditional and complementary medical practices found there was no organized framework to adapt economic evaluation methods to the unique features of TCIM. The reporting of costs and health-related quality of life remained uncommon in TCIM studies. There was a call for updating the guidelines on the evaluation of TCIM and developing better evaluation frameworks (Reference Lin, Ananthakrishnan and Teerawattananon32).

Examples of HTA in Acupuncture

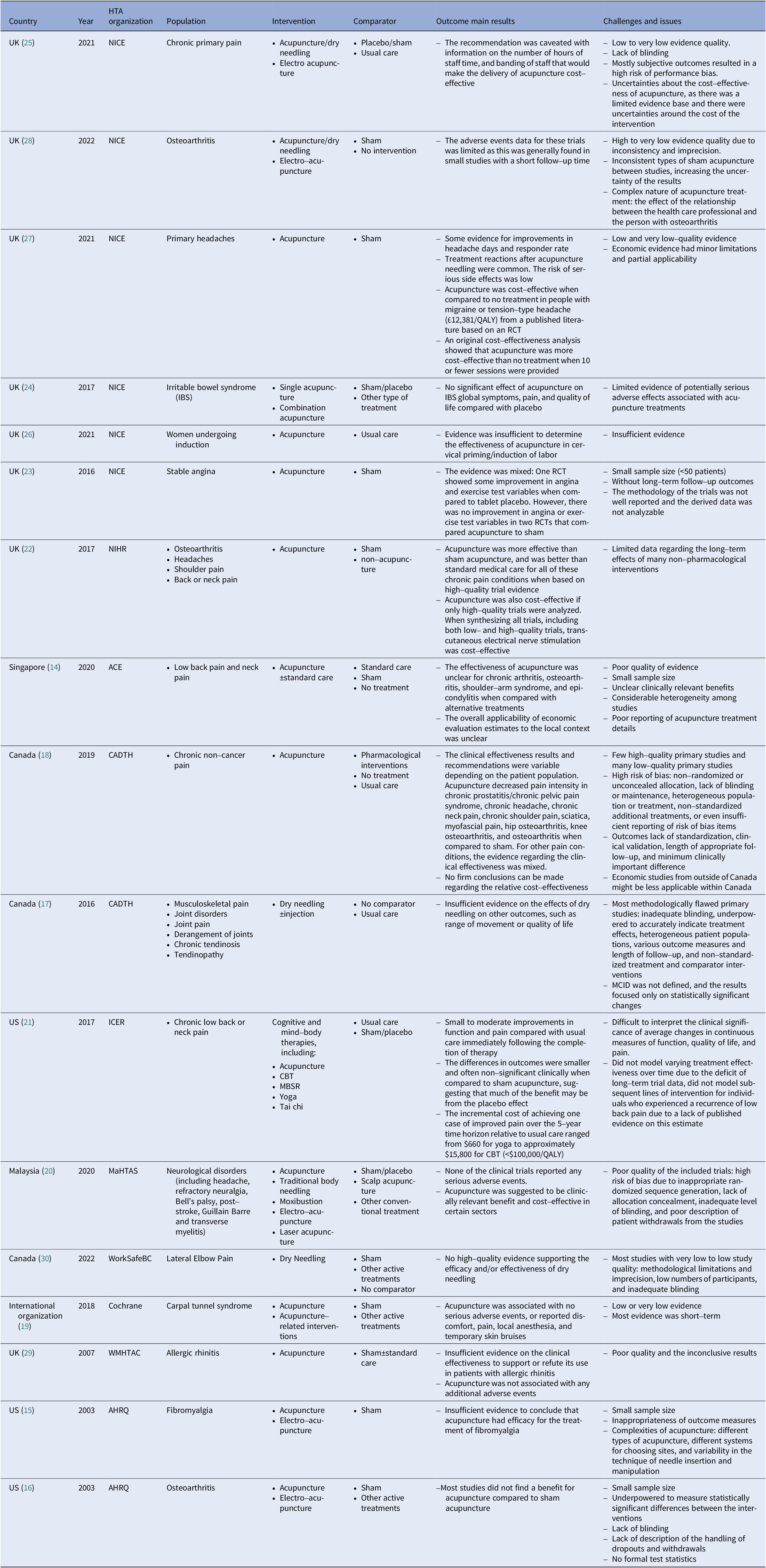

The scoping review identified 17 published acupuncture HTA reports from five countries, including the United Kingdom (8) (Reference MacPherson, Vickers and Bland22–Reference Roberts29), the United States (3) (15;16), (21), Canada (3) (17;18;30), Singapore (1) (14), Malaysia (1) (Reference Fatin and Izzuna20), and one international academic organization, Cochrane (1) (Reference Choi, Wieland and Lee19), between 2003 and 2022. The involved conditions were mainly chronic pain, and otherwise included allergic rhinitis, induction, irritable bowel syndrome, and stable angina. Usual care or a sham/placebo acupuncture were the most common comparators. Detailed characteristics of all included reports are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary characteristics of included acupuncture HTA reports

ACE, Agency for Care Effectiveness; AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CADTH, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; ICER, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review; MaHTAS, Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; WMHTAC, West Midlands Health Technology Assessment Collaboration.

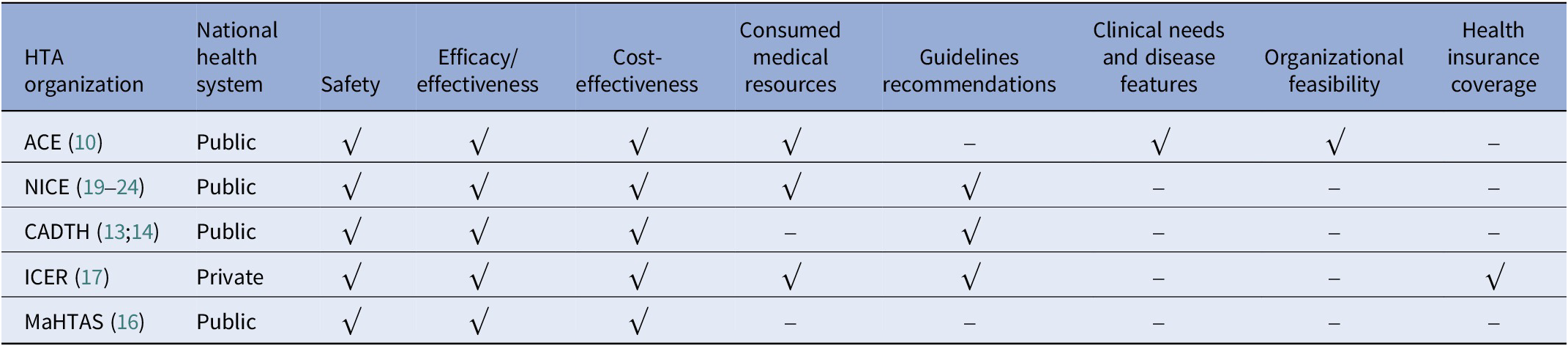

The evaluation dimensions mainly contained safety, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, medical resources consumed, and guideline recommendations (see Table 4). Agency for Care Effectiveness (ACE), a Singaporean HTA organization, also took three other factors, the clinical needs and disease characteristics, organizational feasibility, and ethical or social issues, into consideration (14). The assessment report of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in US mentions health insurance coverage, other important benefits or risks (21). Generally speaking, all evaluation bodies attached importance to the quality of the evidence of safety and effectiveness. In Singapore, guided by the medical device technology guidelines, ACE conducted the evaluation of acupuncture, which predicted the resources utilization with the technology’s annual cost and the number of patients who may benefit from it. The organizational feasibility assessment aimed to identify barriers and facilitate technology’s adaptation into their public healthcare system, and any organizational factors that might influence the technology’s performance or use in clinical practice.

Table 4. HTA domains of acupuncture evaluation

The clinical comparative effectiveness results varied from different patient population in the comparison of acupuncture with placebo or sham acupuncture (14–30). When only synthesizing high-quality clinical evidence, acupuncture was more effective than sham acupuncture or usual care for all of these chronic pain conditions. However, there were plenty of low-quality clinical studies, resulting the inconclusive conclusions. Methodological flaws leading to the generally downgraded evidence quality, were pointed out most frequently. The evidence quality was typically downgraded due to risk of bias and imprecision, like small sample size, inappropriate randomized sequence generation, lack of allocation concealment, inadequate level of blinding, various types of sham acupuncture, considerable heterogeneity among studies, poor reporting of treatment details about interventions and comparators, high placebo response, and non-standardized additional treatments, which finally resulted in unclear and inconsistent clinically relevant benefits. Plus, subjective measures lack of standardization, clinical validation, length of appropriate follow-up, and minimum clinically important difference (MCID) were also challenged. Typically, the continuous outcome results focused only on statistically significant changes, so it was difficult to interpret the clinical significance of average changes in measures of function, quality of life, and pain. Furthermore, although most of the therapies were for chronic pain, long-term follow-up clinical outcomes were not reported in these studies.

Otherwise, the adverse events data for these trials was limited as this was generally found in a few studies with a short follow-up time and so it was unclear whether this was representative of the events expected to be seen in real-life clinical practice. Also, severe adverse reactions were scarce. Considering the beforementioned limitations about clinical effectiveness, there was a limited evidence, and thus many extrapolation assumptions applied in the cost-effectiveness analysis models were lack of robust evidence. The cost-effectiveness results of acupuncture compared with no treatment were inconsistent among various studies, and by limiting the treatment session and duration, acupuncture was likely to become a cost-effective intervention within the country’s threshold (25;27).

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

Overall, there were still no other HTA guideline or consensus of TCIM besides clinical comprehensive evaluation guideline published by academic agencies in China. Typically, the evaluation of TCIM adhered to general guidelines drafted by HTA agencies. The evaluation domains included safety, effectiveness, economy (involving cost effectiveness and consumed medical resources), innovation, suitability, accessibility, specialties of TCM, application, science, standards, guidelines recommendations, clinical needs and disease features, organizational feasibility, health insurance coverage, among which safety, effectiveness, and economy were the most frequent domains.

The role and function of TCIM HTA in policy-making varied across the countries. Despite the fact that forty-five of the WHO member states currently had health insurance coverage for traditional medicine and T&CM practices (e.g., acupuncture and chiropractic) (2). Few countries or regions applied HTA to support medical insurance decision-making for traditional medical services (Reference Chen33), and countries with well-developed HTA knowledge translation mechanism such as the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Switzerland are exploring the use of HTA to support medical insurance access for acupuncture (2;14;Reference MacPherson, Vickers and Bland22–Reference Roberts29). With the need to cover more tradition medical technologies in insurance coverage, evidence-based assessment of its value for money would become a matter of growing importance. There was an appeal to focus on developing better frameworks for evaluating TCIM in order to obtain regulatory approval and/or reimbursement (Reference Lin, Ananthakrishnan and Teerawattananon32).

Compared with other narrative reviews about the status and challenges of HTA and economic evaluation in traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture, this study qualitatively synthesized the value evaluation domains and issues by systematic retrieving evaluation guidelines of TCIM and HTA reports of acupuncture according to the methodology framework of scoping review. It was the first time to synthesize the value evaluation domains of TCIM, even though those domains were mostly consistent with general drug or medical device technology evaluation domains. However, some researchers were appealing and making efforts to add traditional medical-related factors to value framework (Reference Zhang, Liang and Chen10–13;Reference Lin, Ananthakrishnan and Teerawattananon32). Currently, it is evident that economic evaluation plays a limited role in reimbursement decisions for acupuncture (Reference Li, Jin and Herman34). Given that specific healthcare system, costing, healthcare service pathway, and population health preferences, it was difficult to generalize the economic evaluation results to other countries. In terms of the issues, apart from the study design, lack of long-term effectiveness, and poor reporting quality, previous studies also depicted other challenges, such as cost measurement and PICO definition. It was difficult to accurately collect due to dosage and duration adjustment based on the symptoms and characteristics of the patient at each visit, self-pricing and unpublished price. And “Intervention” was not easy to be determined because the number and dosage of traditional medical service were adjusted based on patients’ characteristics and doctors’ experience (Reference Chen33;Reference Yang, Tian and Bai35).

Limitations

There were also several limitations in this article. First of all, studies might have been missed because only peer-reviewed publications or HTA reports released by HTA agencies and written in English or Chinese were considered. Therefore, the included literatures might not be completely representative of the research available. In addition, the study limitations were mainly due to the applicability of generalizing acupuncture assessment domains to traditional non-pharmacological technology assessment, especially considering the specialities of other Chinese medical technology, like tuina, acupotomy, and so on. Furthermore, some included HTA reports might contain inadequate information, leading to insufficient data extraction of the study characteristics of interest, which also restricted the extrapolation of results.

Future Research and Implication

It can be expected value framework of TCIM could expedite the generation and accumulation of high-quality primary evidence. As human-use experience plays an extremely important role in the development of TCIM, real-world diagnosis and treatment data have significant advantages in the effectiveness evaluation of TCIM, which also conduce to address the questions about blindness in RCT and complex peculiarity of traditional non-pharmacological technology to enhance the quality of clinical effectiveness evidence. The well-designed pragmatic randomized clinical trials and other observational studies are very suitable to consider the features of TCIM, which can not only standardize, but also reflect the characteristics of dialectical treatment of Chinese medicine. Recently, eRCT-pRCT-RCDOS-REGOS,Footnote 1 a stepwise progressive clinical effectiveness evaluation system of TCIM was proposed, aimed to enhance study quality by broadening the study populations and interventions to assess the net benefits in more contexts, such as practitioner proficiency, equipment quality, and others (Reference Sun, Li and Liu36). For continuous outcomes, particularly when using a patient-reported outcome measurement tool, researchers should report both statistical and clinical significance, taking MCID into consideration. Considering the wide usage of subject clinical outcomes in the clinical value assessment of TCIM, the study regarding MCID of clinical outcome measures should be encouraged. Categorical measures reporting the proportion of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in function, quality of life, and pain are more useful and should be reported in addition to average group changes. Those factors are beneficial for generating high-quality value evidence for TCIM.

Conclusion

This scoping review provided an overview of the HTA guideline of TCIM and acupuncture HTA reports across various countries. With China vigorously promoting the inheritance and innovation of traditional Chinese medicine and increasingly emphasizing evidence-based decision making, the demand for HTA of TCIM is on the rise, providing evidence for the price adjustment of traditional medical services and the coverage decisions of Chinese patent medicine. Currently, domestic studies about comprehensive value assessment of Chinese patent medicine are on the rise, while few studies address the question of how to assess the value of traditional non-pharmacological technology in order to pursue the decision-makers to purchase traditional and complementary medical services widely. International HTA agencies have published several evaluation reports of acupuncture for various conditions, and the results were used to inform medical insurance reimbursement decisions. The most common assessment domains are clinical effectiveness, safety, and economy. In the process of evidence synthesis, however, some issues, such as poor clinical evidence quality, sophisticated costing, lack of long-term effectiveness, and so on, set obstacles to conclude robust value evaluation results for traditional non-pharmacological technology. In the future, more efforts should be put on how to transform tons of human-usage experience in real-world clinical practice into high-quality evidence. It is a valuable topic to determine if economic evaluation best practice demonstration case is needed for traditional non-pharmacological technology considering these unique features like short-term intervention and potential long-term benefits for physical and mental health, in order to improve study quality and inform scientific decision making.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462324000151.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: D.-D.A., C.-A.-X.D., B.-Y.S., K.Z.; Data extraction: D.-D.A., Q.X., C.-A.-X.D., B.-Y.S.; Literature research and selection: C.-A.-X.D., D.-D.A., Q.X.; Project administration: B.-Y.S., K.Z.; Qualitative analysis: C.-A.-X.D., D.-D.A.; Supervision: K.Z.; Visualization: D.-D.A., C.-A.-X.D.; Writing – Original draft: D.-D.A., B.-Y.S.; Writing – Review and editing: D.-D.A., C.-A.-X.D., K.Z.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.