Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

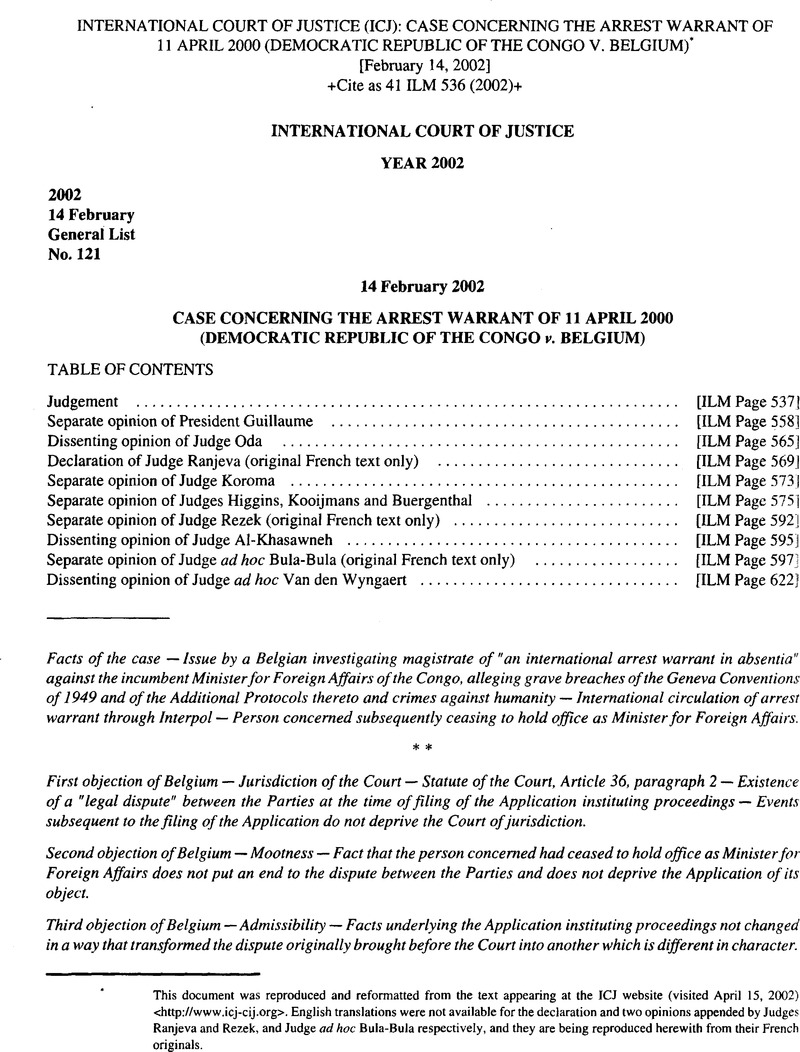

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the ICJ website (visited April 15, 2002) <http://www.icj-cij.org>.English translations were not available for the declaration and two opinions appended by Judges Ranjeva and Rezek, and Judge ad hoc Bula-Bula respectively, and they are being reproduced herewith from their French originals.

1 “Lotus,” Judgment No. 9, 1927, P.C.U., Series A, No. 10 p. 20.

2 Covarruvias, Practicarwn quaestionum Chap. II, No. 7; Grotius, De jure belli ac pacis Book II, Chap. XXI, para. 4; see also Book I, Chap. V.

3 Montesquieu, L'esprit des lois Book 26, Chaps. 16 and 21; Voltaire, Dictionnaire philosophique heading “Crimes et délits de temps et de lieu;” Rousseau, Du contrat social Book II, Chap. 12, and Book III, Chap. 18

4 Beccaria, Traite des délits et des peines para. 21.

5 de Martens, G. F., Précis du droit des gens modernes de I'Europe fonde sur les traites et I'usage 1831, Vol. I, paras. 85 and 86 (see also para. 100).Google Scholar

6 United Nations Reports of International Arbitral Awards (RlAA)t Vol. II, Award of 4 April 1928, p. 838.

7 “Lotus,” Judgment No. 9, 1927, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 10 p. 19.

8 See the Geneva Slavery Convention of 25 September 1926 and the United.Nations Supplementary Convention of 7 September 1956 (French texts in de Martens, Nouveau recueil general des traites 3rd. series, Vol. XIX, p. 303 and Colliard and Manin, Droit international et histoire diplomatique Vol. 1, p. 220).

9 Article 17 of the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, signed at Vienna on 20 December 1988, deals with illicit traffic on the seas. It reserves the jurisdiction of the flag State (French text in Revue générate de droit international public 1989/3, p. 720).

10 League of Nations, Treaty Series (LNTS) Vol. 112, p. 371.

11 United Nations, Treaty Series (UNTS) Vol. 520, p. 151.

12 UNTS Vol. 1019, p. 175.

13 UNTS,Vo\. 860, p. 105.

14 The Diplomatic Conférence at The Hague supplemented the ICAO Legal Committee draft on this point by providing for a nev/ jurisdiction. That solution was adopted on Spain's proposal by a vote of 34 to 17, with 12 abstentions (see Annuaire français de droit international 1970, p. 49).

15 Namely the international conventions mentioned in paragraphs 7 and 8 of the present opinion to which France is party.

16 For the application of this latter Law, see Court of Cassation, Criminal Chamber, 6 January 1998, Munyeshyaka.

17 Court of Cassation, Criminal Chamber, 26 March 1996, No. 132, Javor.

18 Bundesgerkhtshof 13 February 1994, / BGs 100.94 in Neue Zeitschrift für Strafrecht 1994 pp. 232-233. The original German text reads as follows: “4 a) Nach § 6 Nr. I StGB gilt deutsches Strafrecht für ein im Ausland begangenes Verbrechen des Völkermordes (§ 220a StGB), und zwar unabhängig vom Recht des Tatorts (sog. Weltrechtsprinzip). Vorraussetzung ist allerdings — über den Wortlaut der Vorschrift hinaus —, daβ ein völkerrechtliches Verbot nicht entgegensteht und aufierdem ein legitimierender Ankniipfungspunkt im Einzelfall einen unmittelbaren Bezug der Strafverfolgung zum Inland herstellt; nur dann ist die Anwendung innerstaatlicher (deutscher) Strafgewalt auf die Auslandstat eines Ausländers gerechtfertigt. Fehlt ein derartiger Inlandsbezug, so verstöβit die Strafverfolgung gegen das sog. Nichteinmischungsprinzip, das die Achtung der Souveränität fremder Staaten gebietet (BGHSt 27, 30 und 34, 334; Oehler JR 1977, 424; Holzhausen NStZ 1992, 268).“ Similarly, Düsseldorf Oberlandesgericht 26 September 1997,Bundesgerkhtshof 30 April 1999, Jorgić Düsseldorf Oberlandesgericht 29 November 1999, Bundesgerkhtshof 21 February 2001, Sokolvić.

19 Hoge Raad 18 September 2001, Bouterse para. 8.5. The original Dutch text reads as follows: “indien daartoe een in dat Verdrag genoemd aankopingspunt voor de vestiging van rechtsmacht aanwezig is, bijvoorbeeld omdat de vermoedelijke dader dan wel het slachtqffer Nederlander is of daarmee gelijkgesteld moet worden, of omdat de vermoedelijke dader zkh ten tijde van zijn aanhouding in Nederland bevindt.“.

20 House of Lords, 25 November 1998, R. v. Bartle; ex pane Pinochet.

21 “Lotus,” Judgment No. 9, 1927, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 10 p. 19.

22 Ibid p. 20.

23 Ibid p. 20.

24 Ibid. p. 23.

25 Consistency of Certain Danzig Legislative Decrees with the Constitution of the Free City, Advisory Opinion, 1935, P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 65 pp. 41 et seq.

1 Convention des Nations Unies sur le droit de la mer.

2 Convention pour la répression de la capture illicite d'aéronefs

1 Comp. l'arrêt du 5 février 1970 en l'affaire de la Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited (51 pages) avec l'opinion de MM. Ammoun (46 pages), Tanaka (46 pages), Fitzmaurice (49 pages) et Jessup (59 pages); 1'avis du 21 juin 1971 en 1'affaire du Sud-Ouest africain (58 pages) avec l'opinion de Fitzmaurice (102 pages); I'arr6t du 27 juin 1986 en l'affaire des Activites militaries et paramilitaires au Nicaragua et conlre celui-ci (Nicaragua c. Etats- Unis d'Amerique) (150 pages), avec I'opinion de S. M. Schwebel (208 pages); l’arrêt du 16 juin 1992 sur Certaines terres à phosphate à Nauru (29 pages) avec l'opinion de M. Shahabuddeen (30 pages); l’arrêt du 3 juin 1993 en l'affaire de la Délimitation maritime dans la région située entre le Groenland et Jan Mayen (Danemark c. Norvége) (82 pages) avec l'opinion de M. Shahabuddeen (80 pages); l’arrêt du 24 février 1982 en l'affaire du Plateau continental (Tunisie/Jamahiriya arabe libyenne) (94 pages) avec l'opinion S. Oda (120 pages); l’arrêt du 12 décembre 1996 en l'affaire des Plates- formes pétroliéres (République islamique d'Iran c. Etats-Unis d'Amérique) (18 pages) avec l'opinion de M. Shahabuddeen (29 pages).

2 Voir sur ce point, Charles Rousseau, «Les rapports conflictuels,” Droit international public 1.1, Paris, Sirey, 1983, p. 463.

3 Dinh, Nguyen Quoc, Patrick Daillier et Alain Pellet, Droit international public, Paris, Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence, p. 855, par. 541, 1999;Google Scholar Me Whinney, E., Les Nations Unies et la formation du droit, Pédone, Unesco, Paris, 1986, p. 150.Google Scholar

4 Lauterpacht, E., opinion individuelle jointe à I'ordonnance du 17 de'cembre 1997 en l'affaire relative à l’Application de la convention pour la prévention et la répression du crime de gänocide (Croatie c. Yougoslavie), C.I.J. Recueil 1997, p. 278.Google Scholar

5 Voir la communication de Lauterpacht, E., The role of ad hoc judges, Increasing the Effectiveness of the International Court of Justice, Kluwer Law International, The Hague, 1997, p. 370 Google Scholar.

6 Voir le commentaire de Krzystof Skubisevski, ibid. p. 378.

7 S. G. Mesrills, International Dispute Settlement, 2nd edition 1996. p. 125.

8 Voir le commentaire de Krzystof Skubisevski, Increasing the Effectiveness of the International Court of Justice, loc. cit. p. 378.

9 Voir l'intervention de Hugh W. B. Thirlway, ibid. p. 393.

10 Selon le commentaire d'A. Pellet, ibid. «judges ad hoc are very appreciated if they express their opinions during the various phases of thecase,»p. 395.

11 Les événements tragiques qui ont marqué la décolonisation du Congo ont amené l'Organisation des Nations Unies à mettre à contribution la Cour. Voir S. Rosenne, «La Cour intemationale de Justice en I961,” Revue générale de droit international public 3 e série, t. XXX III, octobre-décembre 1962, n° 4, p. 703.

12 Dénommée «conférence nationale souveraine,” le forum s'est tenu de novembre 1991 à décembre 1992. II fut organist parle gouvernement alors en place, sous pression de ses principaux partenaires et finance par ceux-ci, y compris la Belgique.! 3. Conférence nationale souveraine, rapport de la commission des assassinats et des violations des droits de l'homme, p. 18-19.

14 Ibid. témoignage de M. Cléophas Kamitatu, alors president provincial de Léopoldville (Kinshasa).

15 Ibid. p. 26.

16 Ibid. p. 40.

17 Voir G. Abi-Saab, «International Criminal Tribunals, Milanges Bedjaoui Kluwer, La Haye, 1999, p. 651. Voir aussi E. Roucounas, «Time limitations for claims and actions under international law,» ibid. p. 223-240.

18 Ibid. p. 55-56.

19 Ibid, p. 55-56.

20 Voir la Sentence du Tribunal permanent des peuples Rotterdam, le 20 septembre 1982. p. 29.

21 Vok ibid.

22 Voir, ibid. p. 30.

23 Voir, ibid.. p. 32

24 Voir ibid. p. 34.

25 Weston, B. H., Falk, R. A., d'Amato, A., International Law and World Order, 2nd edition, West Publishing Co., St Paul Minn., p. 1286 Google Scholar

26 Au sens de l'article 51 de la Charte de l'Organisation des Nations Unies, précisée par l'article 3 de la resolution 3314 du 14 décembre 1974, confirmé en tant que norme coutumiére par l’arrêt de la Cour du 27 juin 1986 en l'affaire des Activités militaires etparamilitaires au Nicaragua et contre celui-ci (Nicaragua c. Etats-Unis d'Amérique) par. 195.

27 Voir Report of the Panel of Experts on the illegal Exploitation of Natural Ressources and other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sont aussi cités, les sociétés beiges suivantes: Cogem, Muka-Entreprise pour la cassitérite, Soges, Chimie- Pharmacie, Sogem, Cogecom, Cogea, Tradement, Fining Ltd., Cicle International, Special Metal, Mbw et Transitra, pour le coltan, la cassitérite. Source: http://www.un.org/News/dh/latest/drcongo.htm

28 Voir, ibid. par. 109 et suiv. Links between, the exploitation of natural ressources and the continuation of conflict.

29 Voir plaidoiries de la Belgique, CR 2001/11, p. 17-18, par. 8, 9 et 11.

30 Ki-Zerbo, Joseph, «préface à 1'ouvrage de Dicko, Ahamadou A., Journal dune dêfaite. Autour du référendum du 28 septembre 1958 en Afrique noire, Paris, l'Harmattan, Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 1992, p. XIV.Google Scholar

31 Nicolas Politis, La morale international éditions de la Baconniére, Neuchâtel, 1943 (179 pages).

32 Affaire du Detroit de Corfou. C.I.J. Recueil 1949 p. 35.

33 Voir l'opinion de Mendelson, M. H., «Formation of International Law and the Observational Standjoint,« au sujet de «The Formation of Rules of Customary (General) International Law« International Law Association, Report of the Sixty-Third Conférence, p. 944,Warsaw, August 21st to August 27th, 1988 Google Scholar.

34 Voir M. Lachs, opinion individuelle jointe à l'ordonnance du 14 avril 1992 en l'affaire relative à des Questions dinterprétation et d'application de la convention de Montréal de 1971 résultant de I'incident aérien de Lockerbie (Jamahiriya arabe Hbyenne c. Royaume-Uni), C.I.J. Recueil 1992, p. 26.

35 Selon le demandeur, il s'agirait de représentants d'un parti d'opposition fonctionnant à Bruxelles! (Voir compte rendu d'audience publique du 22 novembre 2000, CR 2000/34, p. 20). En revanche, le défendeur excipe des raisons de sécurite devant la Cour (alors que le huis clos est permis) pour ne pas révéler I'identité des plaignants de nationalité congolaise (voir compte rendu de l'audience publique du 21 novembre 2000, CR 2000/33, p. 23).

36 Les quatorze puissances coloniales réunies à Berlin (14 novembre 1884-26 février 1885) avalisèerent le projet colonial du roi Léopold II dénommé «Etat indépendant du Congo.»

37 Le cas est arrivé” a Lomé (Togo) en octobre-novembre 1995 ou un diplomate allemand a été tué par des agents de l'ordre à un barrage routier en début de soirée. L'incident avait gravement déténoré’ les relations germano-togolaises.

38 Mémoire de la République démocratique du Congo, p. 6, par. 8.

39 Voir affaire relative à des Questions d intérpretation et d'application de la convention de Montréal de 1971 résultant de I'incident aérien de Lockerbie (Jamahiriya arabe Hbyenne c. Etats-Unis d'Amérique), C.I.J. Recueil 1998 p. 130, par. 43.

40 CR 2001/10, p. 26; les italiques sont de moi.

41 Mémoire de la République démocratique du Congo, p. 47-61.

42 Voir CR 2001/10, p. 11.

43 Voir CR 2001/10, p. 11; les italiques sont de moi.

44 Voir CR 2001/10, p. 16-17; les italiques sont de moi.

45 Affaire du Détroit de Corfou, fixation du montant des réparations, arrêt du 15 décembre 1949, C.I.J. Recueil 1949 p. 249; affaire relative à la Demande dinterpretation de l’arrêt du 20 novembre 1950 en l'affaire du droit d'asile, (Colombie c. Pérou), arrêt du 27 novembre 1950, C.I.J. Recueil 1950 p. 402.

46 Affaire de la Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, deuxiéme phase, arrêt, C.I.J. Recueil 1970 p. 37, par. 4 contre-mémoire de la Belgique, par. 0.25, 2.74, 2.79, 2.81, 10.2.

47 CR 2001/8, p. 8.

48 CR 2001/8, p.31, par. 54.

49 Charles Rousseau, «Les rapports conflictuels,” Droit international public t. V, Paris, Sirey, 1983, p. 326.

50 CR 2001/8, p. 31, par. 54.

51 Voir Tanaka, opinion individuelle jointe à l'arrêt du 24 juillet 1964 en l'affaire de Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, C.I.J. Recueil 1964 p. 65.

52 Contremémoire de la Belgique, p. 109, par. 3.4.1.

53 Henkin, Louis, Crawford, Richard, Schachter, Oscar, Smit, Hans, International Law West Publishing Co., 1990, p. 1188.Google Scholar

54 Ibid., p. 1191.

55 Voir notamment Jean Salmon, Manuel de droit diplomatique Bruxelles, Bruylant, 1994, p. 539: le ministre des affaires étrangéres jouit «des privilèges et immunités analogues à ceux du chef de gouvemement;» Joe Verhoeven, Droit international public Bruxelles, Larcier, 2000, p. 123: «I1 existe une tendance, au moins doctrinale, a accorder au chef du gouvernement, voire au ministre des affaires étrangères, la protection reconnue au chef de l'Etat.»

56 Affaire du Lotus, arrêt n° 9, 1927, C.P.J.I. Recueil série A n° 10 p. 31.

57 Le préambule de l'Acte général de Berlin du 26 février 1885 rassure sur I'objet et le but du traité: «le bien-être moral et matériel des populations indigènes.»

58 Voir, la communication beige du 14 Kvrier 2001 a laquelle le Congo a répondu le 22 juin 2001.

59 Pierre-Marie Dupuy, «Crimes et immunités,#x0022;#x0020;Revue générale de droit international public t. 105, 1999, n° 2 p. 289-296; les italiques sont de moi.

60 Ibid., p. 293

61 Affaire de la Délimitation de lafrontière maritime dans la region du golfe du Maine, nomination d'expert, arrêt du 12 octobre 1984, C.I.J. Recueil 1984 p. 299; les italiques sont de moi.

62 Diffirend relatifa I'immunite de juridiction dun rapporteur special de la Commission des droits de I'homme paragraphe 67,1b) du dispositif de l'avis consultatif du 29 avril 1999; les italiques sont de moi.

63 lbid.,par. 17.

64 Contre-mémoire, p. 116, par. 3.4.15.

65 Jean-Pierre Cot, A l’éipreuve du pouvoir. Le tiers-mondisme. Pour quoifaire? Editions du Seuil, Paris, 1984, p. 85. L'auteur signale que, alors qu'il éiait ministre de la coopération, il a donné des ordres afin que les coopérants militaires français ne soient pas metes a la répression de la manifestation estudiantine de juin 1981 a Kinshasa.

66 L'absence de mention de «compétence universelle” n'est pas aussi rare dans les travaux des pénalistes eux-mêmes. Voir par exemple André Huet et René Koering-Joulin, Droit pénal international Paris, PUF, 1994.

67 C'est du droit international pénal, branche embryonnaire aux régles éparses et fragmentaires, que ressortit la compétence improprement dite universelle. Cette dernière ne saurait s'affranchir des marques qui caractéi sent sa matrice. D'où le caractere quelque peu nébuleux d'un pouvoir juridique ancien, limité à quelques curiosités historiques telle que la répression de la traite des esclaves, étendu timidement au milieu des XX e siécle à la répression des infractions au droit international humanitaire. C'est de ce dernier que la doctrine et la jurisprudence spécialisées (Tribunal pénal international pour I'ex-Yougoslavie) s'efforcent de lui conferer une autonomie. Puisque la «compétence universelle” telle que revendique'e par la Belgique intéresse la mise en oeuvre coercitive des règles humanitaires genevoises. Que le droit international positif autorise les Etats à sanctionner des infractions commises en dehors de leur territoire lorsque certaines conditions de rattachement à leur souveraineté territoriale sont rdunies n'est pas contestable. Que cette compétence répressive doive être interprétée de manière stricte comme l'exige le droit pénal n'est pas non plus douteux.

68 L'article 49 dispose: «Chaque partie contractante aura 1'obligation de rechercher les personnes prévenues d'avoir commis, ou d'avoir ordonn£ de commettre I'une ou l'autre de ces infractions, et elle devra les déférer à ses propres tribunaux, quelle que soit leur nationalité.

69 Jean Pictet, (dir. pub.), Commentaire de la convention de Genève pour l'amélioration du sort des blessés et des malades dans les forces armiées en campagne Genève, CICR 1952, p. 407.

70 Ibid. p. 409.

71 Ibid., p. 411.

72 Ibid.

73 Voir par exemple 1'article 129, al. 2 de la troisieme convention de Genève du 10 aout 1949.

74 Mémoire de la Republique d£mocratique du Congo, p. 38, par. 57 «abusivement interprétées …” par [les autorités publiques beiges] … [sans] aucune mise en contexte, ni historique, ni culturelle . .. alors que le lien de causalité entre ces paroles et certains actes inqualifiables de violence… est loin dêtre clairement êtabli.” Quant au contre-mémoire du Royaume de Belgique, il reprend (page 11, paragraphs 1.10) les faits tels que repris dans le mandat du 11 avril 2000 aprés avoir annoné «il n'est pas necessaire d'approfondir ces faits qui seront traités brièvement dans la partie III.»

75 Polyakhovich v. Commonwealth of Australia (1991) 172 CLR 581.

76 Article 629 du Code de procédure pénale.

77 C.I.J. Recueil 1986 p. 134, par. 267.

78 Joe Verhoeven, «M. Pinochet, la coutume international et la compétence universelle,» Journal des Tribunaux 1999, p. 315 et du meme auteur «Vers un ordre répressif universel? Quelques observations,* Annuaire franqais de droit international 1999, p. 55. D'autre part, «Que se passeraitil si un plaignant poursuivait devant les tribunaux beiges M. Chirac qui a servi durant la guerre d'Algérie où des massacres ont été commis par I'armée française?#x0022;#x0020;aurait interrogé un haut fonctionnaire israélien à la suite de la plainte déposéepar M. Sharon, premier ministre d'Israël (The Washington Post 30 avril 2001, Washington Post Foreign Service Karl Vick, p. 101: «Death toll in Congo War may approche 3 million»).

79 Voir. S. Oda, déclarations jointes à l'ordonnance du 9 avril 1998 en l'affaire relative à la Convention de Vienne sur les relations consulaires p. 260, par. 2 et à l'ordonnance du 3 mars 1999, p. 18, par. 2, en l'affaire LaGrand (Allemagne c. Etats-Unis dAmérique) sur la nécessité de tenir compte des droits des victimes d'actes de violence (aspect qui a souvent été négligé).

80 Source: International Rescue Committee (USA), www.the IRC.org/mortality.htm

81 Adam Horschild, Lefantôme du Roi lépold. Un holocauste oublée Belfond, Paris, 1998, p. 264-274; Daniel Vangroenweghe, Du sang sur les lianes. Léopold II et son Congo Didier Hâtier, Paris, 1986, p. 18-123; Barbara Emerson, Léopold II. Le Royaume et I'Empire, éditions Soufflot, Paris/éditions Duculot, Gembloux, 1980, p. 248-251.

82 Voir CR 2000/34, p. 16, sur la plaidoirie ace're'e du Congo et Noam Chomsky, «Autopsie des terrorismes,» Paris, Le Serpent a Plumes 2001, p. 12-13. «Les puissances europennes menaient la conquete d'une grande partie du monde, avec une brutalite extrfime. A de tres rares exceptions, ces puissances n'ont pas 6t6 en retour attaquees par leurs victimes …, ni la Belgique par le Congo …»

83 Voir discours de M. Gildas Le Lidec, ambassadeur de France à Kinshasa, le 14 juillet 2001 a l'occasion de la fête nationale de la République française, Le Palmarès, n° 2181, du 16 juillet 2001, p. 8.

84 Pierre-Marie Dupuy, loc. cit. p. 293.

85 Ibid p. 294.

86 Ibid p. 29.

87 François Rigaux, «Le concept de territorialité: un fantasme en quete de réalité.>> in Mélanges Bedjaoui La Haye, Kluwer Law International, 1999, p. 210.

88 Mario Bettati, Le droit d ingétrence. Mutation de I'ordre international Paris, Odile Jacob, 1996, p. 269.

89 Nguyen Quoc Dinh, Patrick Dailler et Alain Pellet, Droit international public Paris, Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence, 1999, p. 689.

90 Olivier T. Covey, «La compétence des Etats,» Droit international. Bilan et perspectives Paris, Pédone, Unesco, 1991, p. 336.

91 Brigitte Stem, «A propos de la compétence universelle,» Mélanges Bedjaoui p. 748.

92 Jean Combacau et Serge Sur, Droit international public Paris, Montchrestien, 1993, p. 351

93 Ph. Weckel, «La Cour pénale internationale,” Revue ginerale de droit international public t. 102, n° 4, 1998, p. 886, 989. D'après les vues d'un pénaliste du Congo, Nyabirungu Mwene Songa, Droit pénal général Kinshasa, editions Droit et société.1995, p. 77 et 79, le «système dit de compétence universelle de la loi pénale donne au juge du lieu d'arrestation le pouvoir de juger.»

94 Voir par. 70 et 71.

95 Voir aussi: S. Bula-Bula, opinion dissidente jointe à l'ordonnance du 8 décembre 2000, par. 16.

96 Voir plaidoirie du 22 novembre 2000, CR 2000/34, p. 10.

97 Voir Le Phare, n° 818 du 28 septembre 1988, p. 3.

98 Voir aussi: S. Bula-Bula, opinion dissidente jointe à l'ordonnance du 8 décembre 2000, par. 17.

99 Paul Guggenheim, Traité de droit international public 1.1, p. 7-8, cité par Krystyna Marek, «Les rapports entre le droit international et le droit interne à la lumière de la jurisprudence de la Cour permanente de Justice internationale,” Revue générate de droit international public t. XXXIII, 1962, p. 276.

100 Affaire relative à Certains intérêts allemands en Haute-Silésie polonaise, fond, arrêt n° 7, 1926, C.P.J.l. série A n” 7 p. 19.

101 Je m'inspire ainsi de l'avis de M. Tarazi, opinion dissidente jointe à l’arrêt du 24 mai 1980, affaire du Personnel diplomatique et consulaire des Etats-Unis à Téhéran, C.I.J. Recueil 1980 p. 64.

102 Raymond Aron, Paix et guerre entre les nations Paris, Caiman-Levy, 1984, p. 389.

103 Paul Reuter et Jean Combacau, Institutions et relations internationales Paris, PUF, Coll. Themis, 1988, p. 24.

104 Sayeman Bula-Bula, «La doctrine d'ingérence humanitaire revisité,Revue africaine de droit international et comparé (Londres), t. 9, n° 3, septembre 1997, p. 626, note 109.

105 Voir Société nationale d'investissement et administration générate de la coopération au développement, Zaire, Secteur des parastataux, réactivation de l'économic Contribution d'entreprise du portefeuille de I'Etat rapport réalisé par M. Moll et J. P. Couvreur et M. Norro, professeurs à l'Université catholique de Louvain, Bruxelles, le 29 avril 1994, p. 231.

106 Voir article 2 du Statut de la Cour Internationale de Justice.

107 Voir Sayeman Bula-Bula, opinion dissidente jointe à l'ordonnance du 8 décembre 2000 rendue en l'affaire du Mandat d arrêt du 11 avril 2000 (République démocratique du Congo c. Belgique) demande en indication de mesures conservatoires, par. 4.

108 D'après Dominique Carreau, Droit international t. I, Paris, Pédone, 2001, p. 653, la Cour accomplit un «role majeur» dans «le developpement du droit international contemporain.»

109 Sayeman Bula-Bula, opinion dissidente jointe à l'ordonnance du 8 décembre 2000 rendue en l'affaire du Mandat d'arrêt du 11 avril 2000 (République démocratique du Congo c. Belgique) demande en indication de mesures conservatoires, par. 7.

110 Paragraphes 70 et 71 de l'arrêt.

111 Voir affaire du Plateau continental de la mer du Nord, C.I.J. Recueil 1969 p. 6 et suiv.

112 Certains font remonter la «compétence universelle” au Moyen Age européen. En cette matière, il faut peut-être se garder de prendre pour universel ce qui n'est probablement que régional. Ainsi, selon E. Ogueri II «the rules of conduct which, for example, governed relations between Ghana and Nigeria in Africa, or between nations in other parts of Africa and Asia, were regarded as universally, recognised customary laws» avant la colonisation. Voir E. Ogueri II, Intervention, International Law Association Report session de Varsovie, 1988, p. 969.

113 Voir Manfred Lachs, opinion individuelle jointe à l’arrêt du 24 mai 1980 rendu dans l'affaire du Personnel diplomatique et consulaire des Etats-Unis à Téhéran, C.I.J. Recueil 1980 p. 47.

114 Mohammed Bedjaoui, La «fabrication» des arrêts de la Cour internationale de Justice, Mélanges Virally Paris, Pédone, 1991, p. 105.

115 Voir Bernard Kouchner, Le malheur des autres Paris, Editions Odile Jacob, 1991 (241 pages).

116 Voir Aimé Césaire, Discours sur le colonialisme Paris, Présence africaine, 1995, p. 8.

117 Sur le militantisme juridique, voir J. Combacau et Serge Sur, Droit international public Paris, Montchrestien, 1993, p. 46; Nguyen Quoc Dinh, Patrick Dallier et Alain Pellet, Droit international public Paris, LGDJ 1992, p. 79. Les auteurs discement un courant occidental du militantisme qui serait représenté par l'Anglais Georg Schwarzenberger et les Américains Myres S. McDougal, Richard Falk et M. Reisman ainsi que l'Anglaise Rosalyn Higgins; un courant oriental sans en pr6ciser les auteurs et un courant du vieux monde

1 The Belgian Foreign Minister, the Belgian Minister of Justice, and the Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Commission House of Representatives, have made public statements in which they called for a revision of the Belgian Act of 1993/1999. The Government referred the matter to the Parliament, where a bill was introduced in Dec. 2001 ﹛Proposition de lot modifiant, sur le plan de la procédure, la loi du 16juin 1993 relative à la répression des violations graves du droit international humanitaire, Doc. Part. Chambre 2001-2002 No. 1568/001, available at http://www.lachambre.be/documentsparlernentaires.html).

2 A. Winants, Le Ministère Public et le droit pénal international, Discours prononcé à l’occasion de I ‘audience solennelle de rentrée de la Cour d'Appel de Bruxelles du 3 septembre 2001 p. 45.

3 Infra paras. 11 et seq.

4 See further infra para. 41.

5 Prominent examples are the Pinochet cases in Spain and the United Kingdom (Audiencia Nacional, Auto de la Sala de lo Pénal de la Audiencia Nacional confirmando la jurisdicción de España para conocer de los crimenes de genocidio y terrorismo cometidos durante la dictadura chilena 5 Nov. 1998, http://www.derechos.org/ nizkor/chile/juicio/audi.html; R. v. Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate and others ex parte Pinochet Ungarte 24 Mar. 1999, All. ER (1999), p. 97), the Qaddafi case in France (Cour de Cassation, 13 Mar. 2001, http://courdecassation.fr/agenda/arrêts/arrêts/00-87215.htm) and the Bouterse case in the Netherlands (Hof Amsterdam, nr. R 97/163/12 Sv and R 97/176/12 Sv, 20 Nov. 2000; Hoge Raad, Strafkamer, Zaaknr. 00749/01 CW 2323, 18 Sep. 2001, http://www.rechtspraak.nl).

6 ECHR (European Commission of Human Rights), Al-Adsani v. United Kingdom 21 Nov. 2001, http://www.echr.coe.int.

7 “Lotus,” Judgment No. 9, 1927, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 10.

8 See further infra footnote 98.

9 Infra para. 41.

10 North Sea Continental Shelf, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1969 p. 44, para. 77.

11 Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986 pp. 97-98.

12 Cour de Cassation (Fr.), 13 Mar. 2001 (Qaddafi).

13 R. v. Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate and others ex parte Pinochet Ungarte 25 Nov. 1998, All. ER (1998), p. 897.

14 Only one case has been brought to the attention of the Court: Chong Boon Kim v. Kim Yong Shik and David Kim Circuit Court (First Circuit), 9 Sep. 1963, AJIL 1964, pp. 186-187. This case was about an incumbent Foreign Minister against whom process was served while he was on an official visit in the United States (see para. 1 of the “Suggestion of Interest Submitted on behalf of the United States,” ibid.). Another case where immunity was recognised, not of a Minister but of a prince, was in the case of Kilroy v. Windsor (Prince Charles, Prince of Wales) District Court, 7 Dec. 1978, International Law Reports Vol. 81, 1990, pp. 605-607. In that case, the judge observes: “The Attorney-General… has determined that the Prince of Wales is immune from suit in this matter and has filed a ‘suggestion of immunity’ with the Court… [T]he doctrine, being based on foreign policy considerations and the Executive's desire to maintain amiable relations with foreign States, applies with even more force to live persons representing a foreign nation on an official visit.” (Emphasis added.)

15 In some States, for example, the United States, victims of extraterritorial human rights abuses can bring civil actions before the Courts. See for example, the Karadzić case (Kadićv. Karadzić 70 F. 3d 232 (2d Cir. 1995)). There are many examples of civil suits against incumbent or former Heads of State, which often arose from criminal offences. Prominent examples are the Aristeguieta case (Jimenez v. Aristeguieta, 1LR 1962, p. 353), the Aristide case (Lafontant v. Aristide WL 20798 (EDNY), noted in AJIL 1994, pp. 528-532), the Marcos cases (Estate ofSilme C. Domingo v. Ferdinand Marcos No. C82-1055V, AJIL 1983, p. 305: Republic of the Philippines v. Marcos and Others (1986), ILR 81, p. 581 and Republic of the Philippines v. Marcos and others 198>, 1988,1LR 81, pp. 609 and 642) and the Duvalier case (Jean-Juste v. Duvalier No. 86-0459 Civ (US District Court, SD Fla.), AJIL 1988, p. 594), all mentioned and discussed by Watts (A. Watts, “The Legal Position in International Law of Heads of States, Heads of Governments and Foreign Ministers,” Recueil des Cours de I'Académie de droit international 1994, III, pp. 54 et seq.). See also the American 1996 Antiterrorism and Effective Death Pénalty Act which amended the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), including a new exception to State immunity in case of torture for civil claims. See J. F. Murphy, “Civil liability for the Commission of International Crimes as an Alternative to Criminal Prosecution,” Harvard Human Rights Journal 1999, pp. 1-56.

16 See also infra para. 48.

17 “Lotus,” supra footnote 7, p. 28. For a commentary, see McGibbon, “Customary international law and acquiescence,” BYB1L 1957, p. 129

18 A. Watts, “The Legal Position in International Law of Heads of States, Heads of Governments and Foreign Ministers,” Recueil des Cours de I'Academie de droit international 1994, III, p. 40.

19 J. Verhoeven, “L'immunite’ de juridiction et d'ex6cution des chefs d'Etat et anciens chefs d'Etat,” Report of the 13th Commission of the Institut de droit international p. 46, para. 18.

20 Convention on Diplomatic Relations, Vienna, 18 Apr. 1961, United Nations, Treaty Series (UNTS) Vol. 500, p. 95.

21 See for example, the Danish hesitations concerning the accreditation of a new ambassador for Israel in 2001, after a new government had come to power in that State: The Copenhagen Post 29 July 2001; The Copenhagen Post 31 July 2001; The Copenhagen Post 24 Aug. 2001 and “Prosecution of New Ambassador?,” The Copenhagen Post 7 Nov. 2001 (all available on the Internet: http://cphpost.periskop.dk).

22 In civil and administrative proceedings this immunity is, however, not absolute. See A. Watts, op. cit. pp. 36 and 54. See also supra footnote 15.

23 See supra footnotes 12 and 13.

24 Convention on Diplomatic Relations, Vienna, 18 Apr. 1961, UNTS, Vol. 500, p. 95 and Convention on Consular Relations, Vienna, 24 Apr. 1963, UNTS Vol. 596, p. 262.

25 Y1LC 1989, Vol. II (2), Part 2, para. 146.

26 A. Watts, op. cit. p. 107.

27 See infra paras. 24 et seq. and particularly para. 32.

28 United Nations Convention on Special Missions, New York, 16 Dec. 1969, Ann. to UNGA res. 2530 (XXIV) of 8 Dec. 1969.

29 J. Salmon observes that the limited number of ratifications of the Convention can be explained because of the fact that the Convention sets all special missions on the same footing, according the same privileges and immunities to Heads of State on a official visit and to the members of an administrative commission which comes negotiating over technical issues. See J. Salmon, Manuel de droit diplomatique Brussels, Bruylant, 1994, p. 546.

30 See also infra para. 75 (inviolability).

31 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes against Internationally Protected Persons, New York, 14 Dec. 1973,78 UNTS p. 277.

32 L. Oppenheim, and H. Lauterpacht, (eds.), International Law, a Treatise Vol. I, 1955, p. 358. See also the 1992 Edition (by Jennings and Watts) at p. 1046.

33 A. Cavaglieri, Corso di Diritto Internationale Second Edition, pp. 321-322.

34 P. Cahier, Le droit diplomatique contemporain 1964, pp. 359-360.

35 J. Salmon, Manuel de droit diplomatique 1994, p. 539.

36 B. S. Murty, The International Law of Diplomacy 1989, pp. 333-334.

37 J. S. de Erice Y O'Shea, Derecho Diplomatico 1954, pp. 377-378.

38 A. WattSj op. cit. p. 106 (emphasis added). See also p. 54 “So far as concerns criminal proceedings, a Head of State's immunity is generally accepted as being absolute as it is for ambassadors, and as provided in Article 31 (1) of the Convention on Special Missions for Heads of States coming within its scope.“

39 A. Watts, op. cit. pp. 109.

40 See the Report of J. Verhoeven, supra footnote 19 (draft resolutions) and the final resolutions adopted at the Vancouver meeting on 26 Aug. 2001 (publication in the Yearbook of the Institute forthcoming). See further H. Fox, “The Resolution of the Institute of International Law on the Immunities of Heads of State and Government,” 1CLQ 2002, p. 119-125.

41 Supra para. 18.

42 ECHR, Al-Adsani v. United Kingdom 21 Nov. 2001, http://www.echr.coe.int. In that case, the Applicant, a Kuwaiti/British national, claimed to have been the victim of serious human rights violations (torture) in Kuwait by agents of the Government of Kuwait. In the United Kingdom, he complained about the fact that he had been denied access to court in Britain because the courts refused to entertain his complaint on the basis of the 1978 State Immunity Act. Previous cases before the ECHR had usually arisen from human rights violations committed on the territory of the respondent State and related to acts of torture allegedly committed by the authorities of the respondent State itself, not by the authorities of third States. Therefore, the question of international immunities did not arise. In the Al-Adsani case, the alleged human rights violation was committed abroad, by authorities of another State and so the question of immunity did arise. The ECHR (with a 9/8 majority), has rejected Mr. Al-Adsani's application and held that there has been no violation of Article 6, paragraph 1, of the Convention (right of access to court). However, the decision was reached with a narrow majority (9/8 and 8 dissenting opinions) and was itself very narrow: it only decided the question of immunities in a civil proceeding, leaving the question as to the application of immunities in a criminal proceeding unanswered. Dissenting judges, Judges Rozakis and Caflisch joined by Judges Wildhaber, Costa, Cabral Barrêto and Vajic and also Loucaides read the decision of the majority as implying that the court would have found a violation had the proceedings in the United Kingdom been criminal proceedings against an individual for an alleged act of torture (para. 60 of the judgment, as interpreted by the dissenting judges in para. 4 of their opinion).

43 Supra footnote 22.

44 Infra paras. 24 et seq.

45 In para. 58 of the Judgment, the Court only refers to instruments that are relevant for international criminal tribunals (the statutes of the Nuremberg and the Tokyo tribunals, statutes of the ad hoc criminal tribunals and the Rome Statute for an International Criminal Court). But there are also other instruments that are of relevance, and that refer to the jurisdiction of national tribunals. A prominent example is Control Council Law No. 10 (Punishment of Persons Guilty of War Crimes, Crimes against Peace and against Humanity, Official Gazette of the Control Council for Germany No. 3, Berlin, 31 Jan. 1946. See also Art. 7 of the 1996 ILC Draft Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of Mankind.

46 Nuremberg Principles, Geneva, 29 July 1950, UNGAOR, 5th Session, Supp. No. 12, United Nations doc. A/1316 (1950).

47 Convention on the Prevention and Suppression of the Crime of Genocide, Paris, 9 Dec. 1948, UNTS Vol. 78, p. 277. See also Art. 7 of the Nuremberg Charter (Charter of the International Military Tribunal, London, 8 Aug. 1945, UNTS Vol. 82, p. 279); Art. 6 of the Tokyo Charter (Charter of the Military Tribunal for the Far East, Tokyo, 19 Jan. 1946, TIAS No. 1589); Art. II (4) of the Control Council Law No. 10 (Control Council Law No. 10, Punishment of Persons Guilty of War Crimes, Crimes against Peace and against Humanity, Berlin, 20 Dec. 1945, Official Gazette of the Control Council for Germany No. 3, Berlin, 31 Jan. 1946); Art. 7, para. 2, of the ICTY Statute (Statute of the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, New York, 25 May 1993, ILM 1993, p. 1192); Art. 6, para. 2, of the ICTR Statute (Statute of the International Tribunal for Rwanda, New York, 8 Nov. 1994, ILM 1994, p. 1598); Art. 7 of the 1996 ILC Draft Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of Mankind (Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind, Geneva, 5 July 1996, YILC 1996, Vol. II (2)) and Art. 27 of the Rome Statute for an International Criminal Court (Statute of the International Criminal Court, Rome, 17 July 1998, ILM 1998, p. 999).

48 See for example, Sub-Commission on Human Rights, Res. 2000/24, Role of Universal or Extraterritorial Compétence in Preventive Action against Impunity 18 Aug. 2000, E/CN.4/SUB.2/RES/2000/24; Commission on Human Rights, Res. 2000/68, Impunity 27 Apr. 2000, E/CN.4/RES/2000/68; Commission on Human Rights, Res. 2000/70, Impunity 25 Apr. 2001, E/CN.4/RES/2000/70 (taking note of Sub-Commission Res. 2000/24).

49 6 Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, The Administration of Justice and the Human Rights of Detainees, Question of the Impunity of Perpetrators of Human Rights Violations (Civil and Political), Revised final report prepared by Mr. Joinet pursuant to Sub-Commission decision 1996/119 2 Oct. 1997, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1997/20/Rev.l; Commission on Human Rights, Civil and political rights, including the questions of: independence of the judiciary, administration of justice, impunity, The right to restitution, compensation and rehabilitation for victims of gross violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Final report of the Special rapporteur, Mr. M. Cherif Bassiouni, submitted in accordance with Commission res. 1999/33 E/CN.4/2000/62.

50 See infra footnote 98.

51 International Law Association (Committee on International Human Rights Law and Practice), Final Report on the Exercise of Universal Jurisdiction in respect of Gross Human Rights Offences 2000.

52 See also the Institut de droit international's Resolution of Santiago de Compostela, 13 Sep. 1989, commented by G. Sperduti “Protection of human rights and the principle of non-intervention in the domestic concerns of States. Rapport provisoire,” Yearbook of the Institute of International Law Session of Santiago de Compostela, 1989, Vol. 63, Part I, pp. 309-351.

53 Princeton Project on Universal Jurisdiction, The Princeton Principles on Universal Jurisdiction 23 July 2001, with a foreword by Mary Robinson, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, http://www.princeton.edu/ ∼lapa/uinive_jur.pdf. See M. C. Bassiouni, “Universal'Jurisdiction for International Crimes: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Practice,” Virginia Journal of International Law 2001, Vol. 42, pp. 1-100.

54 Africa Legal Aid (AFLA), Preliminary Draft of the Cairo Guiding Principles on Universal Jurisdiction in Respect of Gross Human Rights Offenses: An African Perspective Cairo, 31 July 2001, http://www.afla.unimaas.nl/ en/act/univjurisd/preliminaryprinciples.htm.

55 Amnesty Internationa], Universal Jurisdiction. The Duty of States to Enact and Implement Legislation Sep. 2001, AI Index IOR 53/2001.

56 Avocats sans frontières, “Débat sur la loi relative à la répression des violations graves de droit international humanitaire,” discussion paper of 14 Oct. 2001, available on http://www.asf.be.

57 K. Roth, “The Case For Universal Jurisdiction,” Foreign Affairs SepVOct. 2001, responding to an article written by an ex Minister of Foreign Affairs in the same review (Henry Kissinger, “The Pitfalls of Universal Jurisdiction,” Foreign Affairs July/Aug. 2001).

58 See the joint Press Report of Human Rights Watch, the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues and the International Commission of Jurists, “Rights Group Supports Belgium's Universal Jurisdiction Law,” 16 Nov. 2000, available at http://www.hrw.org/press/2000/ll/world-court.htm or http://www.icj.org/press/press01/english/belgiumll.htm. See also the efforts of the International Committee of the Red Cross in promoting the adoption of international instruments on international humanitarian law and its support of national implementation efforts (http://www.icrc.org/eng/ advisory_service_ihl; http://www.icrc.org/eng/ihl).

59 M. C. Bassiouni, “Universal Jurisdiction for International Crimes: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Practice,” Virginia Journal of International Law 2001, Vol. 42, p. 92.

60 Convention on the Non-applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, New York, 26 Nov. 1968, ILM 1969, p. 68.

61 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-personnel Mines and on their Destruction, Oslo, 18 Sep. 1997, ILM 1997, p. 1507.

62 The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) is a coalition of non-governmental organisations, with Handicap International, Human Rights Watch, Medico International, Mines Advisory Group, Physicians for Human Rights, and Vietnam Veterans of Amenca Foundation as founding members.

63 R. v. Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate and others ex parte Pinochet Ungarte, 24 Mar. 1999, All. ER (1999), p. 97.

64 Al-Adsani case: ECHR, Al-Adsani v. United Kingdom 21 Nov. 2001, http://www.echr.coe.int.

65 See American Law Institute, Restatement of the Law Third. The Foreign Relations Law of the United States St. Paul, Minn., American Law Institute Publishers, Vol. 1, para. 404, Comment; M. C. Bassiouni, Crimes Against Humanity in International Criminal Law The Hague, Kluwer Law International, 1999, p. 610; T. Meron, Human Rights and Humanitarian Norms As Customary Law Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1989, p. 263; T. Meron, “International Criminalization of Internal Atrocities,” AJIL 1995, p. 558; A. H. J. Swart, De berechting van ‘Internationale misdrijven Deventer, Gouda Quint, 1996, p. 7; ICTY, Decision on the Defence Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction, 2 Oct. 1995, Tadic paras. 96-127 and 134 (common Art. 3).

66 M. C. Bassiouni, “International Crimes: Jus Cogens and Obligatio Erga Omnes,” 59 Law and Contemporary Problems 1996, pp. 63- 74; M. C. Bassiouni, Crimes against Humanity in International Criminal Law The Hague, Kluwer Law International, 1999, pp. 210-217; C. J. R. Dugard, Opinion In: Re Bouterse para. 4.5.5, to be consulted at: http://www.icj.org/objectives/opinion.htm; K. C. Randall, “Universal Jurisdiction Under International Law,” Texas Law Review 1988, pp. 829-832; ICTY, Judgment, 10 Dec. 1998, Furundžja. para. 153 (torture).

67 See the conclusion of Professor J. Verhoeven in his Vancouver report for the Institut de droit international, supra footnote 19, p. 70.

68 See also supra para. 26.

69 Convention on the Prevention and Suppression of the Crime of Genocide, Paris, 9 Dec. 1948, UNTS Vol. 78, p. 277.

70 “Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind,” ILCR 1996, United Nations doc. 1/51/10.

71 Statute of the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, New York, 25 May 1993, ILM 1993, p. 1192; Statute of the International Tribunal for Rwanda, 8 Nov. 1994, ILM 1994, p. 1598.

72 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Rome, 17 July 1998, ILM 1998, p. 999.

73 Supra footnote 46.

74 See, e.g.. Principle 5 of The Princeton Principles on Universal Jurisdiction. The Commentary states that “There is an extremely important distinction, however, between ‘substantive’ and ‘procedural’ immunity,” but goes on by saying that “None of these statutes [Nuremberg, ICTY, ICTR] addresses the issue of procedural immunity.” ﹛supra footnote 53, pp. 48-51)

75 See the Judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Trial of German Major War Criminals, Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 22, p. 466 “Crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced.“

76 A. Watts, “The Legal Position in International Law of Heads of States, Heads of Governments and Foreign Ministers,” Recueil des Cours de I'Académie de droit international 1994, III, p. 82.

77 See also supra para. 17.

78 Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind, 1LCR 1996, United Nations doc. A/51/10, at p. 41.

79 Supra footnotes 48 and 49.

80 CR 2001/8, para. 5; CR 2001/11, paras. 3 and 11.

81 CR 2001/10, p. 7.

82 G. Fitzmaurice, “The General Principles of International Law Considered from the standpoint of the Rule of Law,” Recueil des Cours de I'Academie de droit international 1957, II (Vol. 92), p. 119 writes: “'He who comes to equity for relief must come with clean hands.’ Thus a State which is guilty of illegal conduct may be deprived of the necessary locus standi injudicio for complaining of corresponding illegalities on the part of other States, especially if these were consequential on or were embarked upon in order to counter its own illegality — in short were provoked by it.“ See also S. M. Schwebel, “Clean Hands in the Court,” in Brown, E. Weiss, et al. (eds.), The World Bank, International Financial Institutions, and the Development of International Law American Society of International Law, 1999, pp. 74-78 and Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986 dissenting opinion of Judge Schwebel, pp. 382-384 and 392-394.

83 H. Lauterpacht, “The Problem of Jurisdictional Immunities of Foreign States,” BYBIL 1951, p. 232.

84 See also para. 55 of the Judgment, where the Court says that, from the perspective of his “full immunity,” no distinction can be drawn between acts performed by a Minister of Foreign Affairs in an “official capacity” and those claimed to have been performed in a “private capacity.“

85 See supra footnotes 12 and 13.

86 R. v. Bow Street Metropolitan Stipendiary Magistrate and others ex parte Pinochet Ugarte 25 Nov. 1998, All. ER (1998) 4, p. 945.

87 See for example, the trial of four Rwandan citizens by a Criminal Court in Brussels: Cour d'Assises de I'Arrondissement Administratif de Bruxelles-Capitale, Arrêt du 8juin 2001 not published.

88 See also infra para. 65.

89 C. Tomuschat, Intervention at the Institut de droit international's meeting in Vancouver, Aug. 2001, commenting on the draft resolution on Immunities from jurisdiction and Execution of Heads of State and of Government in International law, and giving the example of Iraqi dictator Sadam Hussein: Report of the 13th Commission of the Institut de droit international, Vancouver, 2001, p. 94, see further supra footnote 19 and corresponding text.

90 On the subject of inviolability, see infra para. 75.

91 Loi du 16 juin 1993 relative à la répression des violations graves du droit international humanitaire, Moniteur beige 5 aout 1993, as amended by Loi du 10 février 1999, Moniteur beige 23 mars 1999; an English translation has been published in ILM 1999, pp. 921-925. See generally: A. Andries, C. Van den Wyngaert, E. David, and J. Verhaegen, “Commentaire de la loi du 16 juin 1993 relative à la répression des infractions graves au droit international humanitaire,” Rev. Dr. Pén. 1994, pp. 1114-1184; E. David, “La loi beige s les crimes de guerre,” RBDI 1995, pp. 668-684; P. d'Argent, “La loi du 10 février 1999 relative a la répression des violations grave du droit international humanitaire,” Journal des Tribunaux 1999, pp. 549-555; L. Reydams, “Universal Jurisdiction over Attrocities in Rwanda: Theory and Practice,” European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, 1996, pp. 18-47; D. Vandermeersch, “La répression en droit beige des crimes de droit international,” RIDP 1997, pp. 1093-1135; Vandermeersch, “Les poursuites et le jugement des infractions de droit international humanitaire en droit beige” in D. H. Bosly et al., Actualité du droit international humanitaire Bruxelles, La Charte, 2001, pp. 123-180; J. Verhoeven, “Vers un ordre répressif universel? Quelques observations,” Annuaire Français de Droit International 1999, pp. 55-71.

92 For a survey of the implementation of the principle of universal jurisdiction for international crimes in different countries, see, inter alia: Amnesty International, Universal Jurisdiction. The Duty of States to Enact and Implement Legislation Sep. 2001, AI Index IOR 53/2001; International Law Association (Committee on International Human Rights Law and Practice), Final Report on the Exercise of Universal Jurisdiction in respect of Gross Human Rights Offences Ann., 2000; Redress, Universal Jurisdiction in Europe. Criminal prosecutions in Europe since 1990 for war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture and genocide 30 June 1999: http://www.redress.org/inpract.html; see also “Crimes intenationaux et juridictions rationales” to be published by the Presses Universitaires de France (in print).

93 Attorney-General of the Government of Israel v. Eichmann 36ILR 1961 p. 5. See also US v. Yunis (No. 2), District Court, DC, 12 Feb. 1988, ILR 1990, Vol. 82, p. 343; Court of Appeals, DC, 29 January 1991, ILM 1991, Vol. 3, p. 403.

94 Audiencia Nacional, Auto de la Sala de lo Pénal de la Audiencia Nacional confirmando la jurisdicción de España para conocer de los crimenes de genocidio y terrorismo cometidos durante la dictadura chilena,5 Nov 1998 http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/chile/juicio/audi.html. See also M. Marquez Carrasco and J. A. Fernandez, “Spanish National Court, Criminal Division (Plenary Session). Case 19/97,4 Nov. 1998, Case 1/98,5 Nov. 1998,” AJIL 1999, pp. 690-696.

95 CR 2001/8, p. 16.

96 Some confusion arose over the difference between the notion of “victim” and the notion of “complainant” (partie civile). Belgian law does not provide an actio popularis but only allows victims and their relatives to trigger criminal investigations through the procedure of a formal complaint (constitution de partie civile). On the Belgian system, see C. Van den Wyngaert, “Belgium,” in C. Van den Wyngaert, et al. (ed.), Criminal Procedure Systems in the Member States of the European Community Butterworth, 1993.

97 The notion “victim” is wider than the direct victim of the crime only, and also includes indirect victims (e.g., the relatives of the assassinated person in the case of murder). Moreover, for crimes such as those with which Mr. Yerodia has been charged (incitement to war crimes and crimes against humanity), death or injury of the (direct) victim is not a constituent element of the crime. Not only those who were effectively killed or injured after the alleged hate speeches are victims, but all persons against whom the incitements were directed, including the victims of Belgian nationality who brought the case before the Belgian investigating judge by lodging a constitution de partie civile action. By focusing on the victims of the violence in para. 15 of the Judgment, the International Court of Justice seems to adopt a very narrow definition of the notion of victim.

98 For a very thorough recent analysis of the various positions, diachronically and synchronically, see M. Henzelin, Le principe de Vuniversalité en droit pénal international. Droit et obligation pour les Etats de poursuivre etjuger selon le principe de I'universalité Brussel, Bruylant, 2000, p. 527. Other recent publications are M. C. Bassiouni, “Universal Jurisdiction for International Crimes; Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Practice,” Virginia Journal of International Law 2001, Vol. 42, pp. 1-100; L. Benavides, “The Universal Jurisdiction Principle,” Annuario Mexicano de Derecho Internacional 2001, pp. 20-96; J. I. Charney, “International Criminal Law and the Role of Domestic Courts,” AJIL 2001, pp. 120-124; G. de La Pradelle, “La Compétence Universelle,” in H. Ascensio, et al. (eds.), Droit International Pénal Paris, A. Pedone, 2000, pp. 905-918; A. Hays Butler, “Universal Jurisdiction: A Review of the Literature,” Criminal Law Forum 2000, pp. 353-373; R. van Elst, “Implementing Universal Jurisdiction over Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions,” LJIL 2000, pp. 815-854. See also the proceedings of the symposium on Universal Jurisdiction: myths, realities, and prospects, New England Law Review 2001, Vol. 35.

99 For example, some writers hold the view that an independent theory of universal jurisdiction exists with respect to jus cogens international crimes. See for example, M. C. Bassiouni, “Universal Jurisdiction for International Crimes: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Practice,” Virginia Journal of International Law 2001, Vol. 42, p. 28.

100 “Les juridictions beiges sont compétentes pour connaître des infractions prévies à la présente loi, indépendamment du lieu où celles-ci auront été commises.” See footnote 91 for further reference.

101 Supra footnote 53.

102 Supra footnote 54.

103 Supra footnote 51.

104 “Lotus,” Judgment No. 9, 1927, P.C.I.J., Series A, No. 10 p. 19.

105 Ibid. p. 18.

106 See infra paras. 68 et seq.

107 Cf:American Law Institute, Restatement (Third) Foreign Relations Law of the United States, (1987), pp. 235-236; I. Cameron, The Protective Principle of International Criminal Jurisdiction Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1994, p. 319; F. A. Mann, “The Doctrine of Jurisdiction in International Law,” Recueil des Cours de l'Académie de droit international Vol. Ill, 1964, I, p. 35; R. Higgins Problems and Process. International Law and How We Use It Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1994, p. 77. See also Council of Europe, Extraterritorial jurisdiction in criminal matters Strasbourg, 1990, pp. 20 et seq.

108 Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1996, pp. 16-17, para. 21.

109 I.C.J. Reports 1996 p. 270, para. 12.

110 Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, 12 Aug. 1949, UNTS Vol. 75, p. 287. See also Art. 49 Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, Geneva, 12 Aug. 1949, UNTS Vol. 75, p. 31; Art. 50 Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea, Geneva, 12 Aug. 1949, UNTS Vol. 75, p. 85; Art. 129 Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva, 12 Aug. 1949, UNTS Vol. 75, p. 135; Art. 85 (1) Protocol Additional (I) to the Geneva Conventions of 12 Aug. 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts, Geneva, 8 June 1977, UNGAOR doc. A/32/144, 15 Aug. 1977.

111 See further infra para. 62.

112 See, e.g. the Swiss Pénal Code, Art. 6bis 1; the French Pénal Code, Art. 689-1; the Canadian Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Act (2000), Art. 8.

113 Public Prosecutor v. T., Supreme Court (Hojesteret), Judgment, 15 Aug. 1995, Ugeskrift for Retsvaesen 1995, p. 838, reported in Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law 1998, p. 431 and in R. Maison, “Les premiers cas d'application des dispositions pénales des Conventions de Genève: commentaire des affaires danoise et française,” EJIL 1995, p. 260.

114 Cour de Cassation (Fr.), 26 Mar. 1996, Bull. Crim. 1996, pp. 379-382.

115 Bundesgerichtshof 30 Apr. 1999, 3 StR 215/98, NStZ 1999, p. 396. See also the critical note (Anmerkung) by Ambos, ibid. pp. 405- 406, who doesn't share the view of the judges that a “legitimizing link” is required to allow Germany to exercise its jurisdiction over crimes perpetrated outside its territory by foreigners against foreigners, even if these amount to serious crimes under international law (in casu genocide). In a recent judgment concerning the application of the Geneva Conventions, the Court, however, decided that such a link was not required, since German jurisdiction was grounded on a binding norm of international law instituting a duty to prosecute, so there could hardly be a violation of the principle of non-intervention (Bundesgerichtshof, 21 Feb. 2001, 3 StR 372/00, retrievable on http://www.hrr-strafrecht.de).

116 See for example, the prosecutions instituted in Spain on the basis of Art. 23.4 of the Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial (Law 6/1985 of 1 July 1985 on the Judicial Power) against Senator Pinochet and other South-American suspects whose extradition was requested. In New Zealand, proceedings may be brought for international “core crimes” regardless of whether or not the person accused was in New Zealand at the time a decision was made to charge the person with an offence (Sec. 8, (\)(c) (iii) of the International Crimes and International Criminal Court Act 2000).

117 The German Government very recently reached agreement on a text for an “International Crimes Code” (Völkerstrafgesetzbuch) (see Bundesministerium der Justiz, Mitteillung für die Presse 02/02 Berlin, 16 Jan. 2002). The new code would allow the German Public Ministry to prosecute cases without any link to Germany and without the presence of the offender on the national territory. The Prosecutor would only be obliged to defer prosecution in such a case when an International Court or the Courts of a State basing its jurisdiction on territoriality or personality were in fact prosecuting the suspect (see Bundesministerium der Justiz, Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Einführung des Völkerstrafgesetzbuches, pp. 19 and 89, to be consulted on the Internet: http://www.bmj.bund.de/images/11222.pdf).

118 See supra footnote 5. The Court of Appeal of Amsterdam had, in its judgment of 20 Nov. 2000, decided, inter alia that Mr. Bouterse could be prosecuted in absentia on charges of torture (facts committed in Surinam in 1982). This decision was reversed by the Dutch Supreme Court on 18 Sep. 2001, inter alia on the point of the exercise of universal jurisdiction in absentia. The submissions of the Dutch Advocate General are attached to the judgment of the Supreme Court, loc. cit. paras. 113-137 and especially para. 138.

119 See supra para. 13.

120 ECHR, Al-Adsani v. United Kingdom 21 Nov. 2001, para. 18 and the concurring opinions of Judges Pellonpää and Bratza, retrievable at: http://www.echr.coe.int. See the discussion in Marks, “Torture and the Jurisdictional Immunities of Foreign States,” CLJ 1997, pp. 8- 10.

121 See Journal Officiel de l'Assemblée nationale 20 décembre 1994, 2 e stance, p. 9446.

122 For recent sources see supra footnote 98

123 Supra footnote 53.

124 Supra, footnote 54.

125 Supra footnote 51.

126 Although the wording of Princeton Principle 1(2) may appear somewhat confusing, the authors definitely did not want to prevent a State from initiating the criminal process, conducting an investigation, issuing an indictment or requesting extradition when the accused is not present, as is confirmed by Principle 1(3). See the Commentary on the Princeton Principles at p. 44.

127 On the subject of genocide and the Genocide Convention of 1948, the International Court of Justice held that “the rights and obligations enshrined by the Convention are rights and obligations erga omnes” and “that the obligation each State thus has to prevent and to punish the crime of genocide is not territorially limited by the Convention” (Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Preliminary Objections, I.C.J. Reports 1996 (II), p. 616, para. 31.

128 See supra, footnote 110.

129 See International Committee of the Red Cross, National Enforcement of International Humanitarian Law: Universal Jurisdiction Over War Crimes retrievable at: http://www.icrc.org/; R. van Elst, “Implementing Universal Jurisdiction over Grave Breaches of the Geneva Conventions,” LJIL 2000, pp. 815-854.

130 Guillaume, “La compétence universelle. Formes anciennes et nouvelles,” X, Mélanges offerts à Georges Levasseur Paris, Editions Litec, 1992, p. 27.

131 Slavery Convention, Geneva, 25 Sep. 1926,60 League of Nations, Treaty Series (LNTS) p. 253.

132 International Convention for the Suppression of Counterfeiting Currency, Geneva, 20 Apr 1929, LNTS p. 371, para. 112.

133 Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, signed at The Hague on 16 Dec. 1970, ILM 1971, p. 134.

134 Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman of Degrading Treatment of Punishment, New York, 10 Dec. 1984, ILM 1984. p. 1027, with changes in ILM 1985, p. 535..

135 The Geneva Conventions of 1949 are unique in that they provide a mechanism which goes further than the ‘aut dedere, aut judicare” model and which can be described as “autjudicare, aut dedere,” or, even more poignantly, as “primoprosequi, secundo dedere.” See respectively, R. van Elst, loc. cit. pp. 818-819; M. Henzelin, op. cit. p. 353, para. 1112.

136 See M. Henzelin, op. cit. p. 354, para. 1113.

137 See Memorial of the Congo, p. 59, “Obligation de ne pas priver le Statut de la C.P.I, de son objet et de son but.“

138 See footnotes 48 and 49.

139 See also supra para. 37.

140 Mr. Yerodia's visit to Belgium is not mentioned in the judgment because the parties were rather unclear on this point. Yet, it seems that Mr. Yerodia effectively visited Belgium on 17 June 2000. This was reported in the media (see the statement by the Minister of Foreign Affairs in De Standaard 7 July 2000) and also in a question that was put in Parliament to the Minister of Justice. See Question orale de M. Tony Van Parys au ministre de la Justice sur “l'intervention politique du gouvernement dans le dossier à charge du minister congolais des Affaires étrangères, M. Yerodia,” Chambre des représentants de la Belgique, Compte Rendu Intégral avec compte rendu analytique Commission de la Justice, 14 Nov. 2000, CRIV 50 COM 294, p. 12. Despite the fact that this fact is not, as such, recorded in the documents that were before the International Court of Justice, I believe the Court could have taken judicial notice of it.

141 Supra para. 18.

142 See the statement of the International Law Commission's special rapporteur, referred to supra para. 17.

143 CR 2001/5, p. 14.

144 CR 2000/32.

145 Convention on Diplomatic Relations, Vienna, 18 Apr. 1961, UNTS Vol. 500, p. 95.

146 J. Salmon, Manuel de droit diplomatique Brussels, Bruylant, 1994, p. 304

147 J. Brown, “Diplomatic immunity: State Practice Under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations,” 37 ICLQ 1988, p. 53.

148 Supra para. 49.

149 See the Proposal for a Council Framework Decision on the European Arrest Warrant and the Surrender Procedures between the Member States COM(2001)522, available on the Internet: http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/com/ pdf/2001/en_501PC0522.pdf. An amended version can be found in: Council of the European Union, Outcome of proceedings, lODec.2001,14867/1/01 REV 1 COPEN 79 CATS 50.

150 Often, governments refrain from requesting extradition for political reasons, as was shown in the case of Mr. Ocalan, where Germany decided not to proceed to request Mr. Ocalan's extradition from Italy. See Press Reports: “Bonn stellt Auslieferungsersuchen für Öcalan zurück,” Frankfürter Allgemeine 21 Nov. 1998 and “Die Bundesregierung verzichtet endgültig auf die Auslieferung des Kurdenführers Öcalan,” Frankfürter Allgemeine 28 Nov. 1998.

151 Interpol, Secretariat général, Rapport sur la valeur juridique des notices rouges ICPO — Interpol — General Assembly, 66th Session, New Delhi, 15-21 Oct. 1997, AGN/66/RAP/8, No. 8 Red Notices, as amended pursuant to res. No. AGN/66/RES/7.

152 See the Danish hesitations concerning the accreditation of an Ambassador for Israel, supra footnote 21.

153 CR 2001/10/20.

154 See Art. 14 of the 2001ILC Draft Articles on State Responsibility, United Nations doc. A/CN.4/L.602/Rev. 1, concerning the extension in time of the breach of an international obligation, which states the following: “1. The breach of an international obligation by an act of a State not having a continuing character occurs at the moment when the act is performed, even if its effects continue. 2. The breach of an international obligation by an act of a State having a continuing character extends over the entire period during which the act continues and remains not in conformity with the international obligation …“

155 Questions of Interpretation and Application of the 1971 Montreal Convention arising from the Aerial Incident at Lockerbie (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. United Kingdom), Preliminary Objections, I.C.J. Reports 1998 p. 23, para. 38 (jurisdiction) and p. 26, para. 44 (admissibility). See further S. Rosenne, The Law and Practice of the International Court, 1920-1996 Vol. II, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1997, pp. 521-522.

156 In the Questions of Interpretation and Application of the 1971 Montreal Convention arising from the Aerial Incident at Lockerbie (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya v. United Kingdom) case the Court only decided on the points of jurisdiction (ibid., Preliminary Objections, I.C.J. Reports 1998 p. 30, para. 53(1)) and admissibility (ibid. para. 53 (2)), not on mootness (ibid. p. 31, para. 53(3)). The ratio decidendi for paras. 53(1) and (2) is that the relevant date for the assessment of both jurisdiction and admissibility are the date of the filing of the Application. The Court did not make such a statement in relation to mootness.

157 See supra para. 35.

158 This expression is not synonymous to de minimis non curat praetor in civil law systems. See Black's Law Dictionary West Publishing Co.

159 See supra para. 37.

160 60 J. Verhoeven, “M. Pinochet, la coutume Internationale et la compétence universelle,” Journal des Tribunaux 1999, p. 315; J. Verhoeven, “Vers un ordre répressif universel? Quelques observations,” AFDI1999, p. 55.