The War and the Labour Question

Historians of the Ottoman Empire during World War I have asked the question: how did “the sick man of Europe” fight four years in a World War?Footnote 1 The same question was not so readily posed of the ailing British Empire in the 1940s. In the context of India, how was the waning colonial state able to mobilize a subcontinent-sized territory, with a long history of anti-colonialism, for an imperial war effort and with what consequences? There are some clues in what historians have written up until now. In terms of Britain's Asian colonies, Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper were among the first historians to draw our attention to the grave impacts of the war, which must have been evident to contemporaries. They went as far as to refer to a “Great Asian War”, which continued to devastate and destabilize the whole region of Southeast Asia even after the conflict in Europe had ended.Footnote 2 It spelt the end of the empire and presented possibilities for a new postcolonial future.

For the case of the Indian subcontinent, Yasmin Khan has written a broad “People's History” of the Indian “home front” during the war, discussing the enormous costs and consequences of the war for the maintenance of the Raj.Footnote 3 In an issue of Social Scientist, a number of scholars focused on how the war shaped the complex and diverse processes of decolonization – Adivasi politics, Hindu Mahasabha politics, and the transition to Congress Raj in Orissa.Footnote 4 These writings have begun to explore and outline the role of the war as a watershed in the history of not just the end of the empire but, as Srinath Raghavan has argued, the making of Modern South Asia.Footnote 5 In our view, Indivar Kamtekar has provided the most precise framework for understanding the 1940s.Footnote 6 He has argued that the war simultaneously expanded the state and made it vulnerable to society. Contradictory pressures of the war produced a “sharp crisis”, and the old ways of governing collapsed in the post-war period. But the state survived and its reach in society deepened.Footnote 7

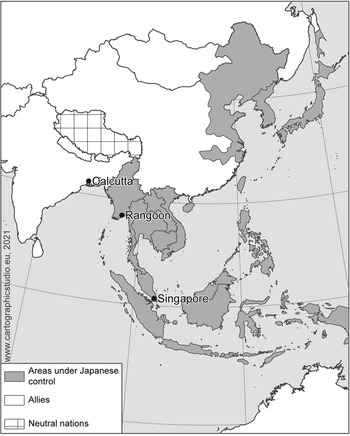

The crisis of the state and social power was felt acutely in the workplaces and was shaped by it, so much so that the late 1940s formed a “catalytic moment for the definition of labour as a political category”, as Ravi Ahuja has argued.Footnote 8 As the British Empire entered the World War II, immense uncertainties surrounded the labour question. Globally, we know that the dock workers were at the forefront of labour militancy in the 1940s, as well as at the centre of implementation of the post-war social policies.Footnote 9 In such a scenario, the port of Calcutta, which served as an important military port in Southeast Asia after the fall of Singapore and Rangoon (Figure 1), provides a fine vantage point for beginning to investigate the dramatic changes that a global war brought for Indian workers’ everyday lives, for industrial relations, for the politics of labour, and for the shape of decolonization. This article explores workers’ wartime experiences and a changing labour regime at the Calcutta docklands, contributing to the recent trend of narrating transnational histories of World War II, which go beyond the elite actors of Great Powers, and illuminate uneven and connected processes that shaped war and peace in societies worldwide.Footnote 10

Figure 1. Calcutta in the Pacific theatre of World War II (1941–1945).

Scholarship about labour during wartime in the Indian subcontinent remains scant. Historians of African workers have studied the acute conundrums and contradictions presented by the “international world of labour created by imperialism and two world wars” for the imperial administrators: drawing comparisons with metropolitan workers; claiming of universal rights, for instance the demand among workers of French West Africa for a labour code similar to the one in France; coercive recruitment; intensity of strike action.Footnote 11 In the existing scholarship on India, evidence from two major industries of colonial India – Calcutta's jute mills and Bombay's textile mills – indicates the high concentration of the strains of the war on the existing labour regime and the impetus for industry-wide changes in employment conditions.Footnote 12 Changes not only occurred at the level of industries, the state's functions with respect to labour considerably expanded, including the setting up of the Department of Labour under the Government of India in 1942 and the introduction of rationing in the same year. These were precursors to a new regime of state-centred industrial relations in the postcolonial period, forged in the face of an unprecedented strike wave in the post-war period. It was consolidated by means of extensive legislative and institutional measures that divided working classes into a more privileged “formal sector”, regulated by the state, and the largely unregulated “informal sector”.Footnote 13

Even if the role of employers, the state, and jobbers has been examined to some extent in Indian historiography, the role of workers in these momentous years has often remained in the background. This article contributes by juxtaposing a study of the changes in labour regime in the long run with that of the extraordinary, distinct, wartime experiences of workers. The first and more usual approach to investigating the labour regime from above, as it were, shows us how extensive the changes driven by wartime exigencies were, and how deeply these impacted the existing labour relations. The scale and intensity of changes at the docks seem to surpass even the textile or jute mills. A perspective “from below” illuminates workers’ wartime experiences and allows us to partly explain why these changes catalysed a transformation. The article situates changes in work organization in a highly volatile environment of wartime docks, revealing an ongoing “war” at the workplace through strikes and strike threats after the fall of British colonies in the Far East, labour flight during bombings, petitioning over food rations, and rising shop-floor tensions.

At the scale of the wider city and the region, historians of Bengal have recognized the 1940s as a time of crisis, of churning, as a decade in which it seemed that “all that is solid melt[ed] into air”.Footnote 14 Even so, the significance of the war may have been overshadowed by more familiar themes – famine, independence, partition, and the role of the left. An exception is Srimanjari's work: a multifaceted study of wartime Bengal showing the diversity of experiences of various segments of society – especially the rising destitution of rural women.Footnote 15 Janam Mukherjee's work on the connected history of war and famine uses famine as the “primary hermeneutic” to emphasize the implications of the death of at least three million people by starvation for the social and political history of Bengal.Footnote 16 This work reminds us of a contemporary novel, set in Calcutta and its hinterland, So Many Hungers, which uses hunger as an evocative metaphor to lay bare how the war moved the colonized people, from a middle-class “housewife”, to a peasant, to a scientist.Footnote 17

Wartime labour experiences assume significance in this context, more so, given that the interwar period saw the emergence of an unusually militant labour movement and a proliferation of communist and revolutionary groups in the workplaces. Significantly, alternative communist groups remained influential in the 1930s in the docklands, whereas the influence of the Communist Party of India (CPI), the largest communist organization, remained marginal, a situation that offers an interesting contrast to Bombay's textile mills. In any case, the trade unions and political organizations of workers faced the full brunt of state repression, as any activist seen as anti-war was simply arrested or “externed” to a place outside the city as early as 1940. The most influential union, the Calcutta Port Trust Employees Association (CPTEA), became disorganized too. This left the field for the CPI, which collaborated in the war effort from the spring of 1942 and quickly gained a foothold in the leadership and union apparatus of the CPTEA. Although historians have remarked that the CPI support among workers waned during the war, the party's rise in the trade union leadership strengthened reformist tendencies within the docklands’ unions, but exploring this would require a separate article.Footnote 18 For the purposes of this article, our focus is on how workers related to their new circumstances. My research reveals great dissonances at work: as the whole labour regime was in flux, intense covert and open labour conflicts can be discerned in this period, while the CPI, through its local Kidderpore cell, was advocating a policy of unhindered cooperation with the employers in the war effort.

The story of labour during the war is not primarily one of workers’ anti-colonial and anti-war resistance and even less one of loyalty to the empire. It is difficult to frame the war period as a singular experience for workers. With the dramatic changes in the work organization and in the political climate, and as a result of the bombings and the famine, the balance between workers’ enhanced bargaining power and employers’ exploitative tendencies, between workers’ militancy and state's repressive powers, and between the requirements of efficiency and the need for discipline, was constantly shifting. Such fluid circumstances widened the possibilities for the politics of labour, while at the same time strong counterforces of stabilisation were also at work; it is in these processes that the paper aims to situate workers’ wartime experiences.

Shaking the Old Labour Regime

“Efficiency? Hell, we went down the Hooghly to meet the boats!”Footnote 19

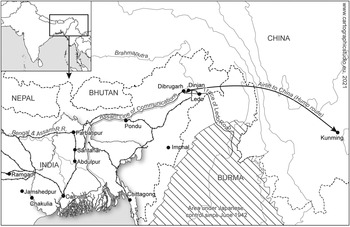

Although the American sergeant quoted above was understandably shocked at the “backwardness” of one of the major ports of the British Empire, the war rapidly transformed the industrial face of the subcontinent. Employment in factories increased by 59 per cent between 1939 and 1945, to take just one indicator.Footnote 20 Located in the East and thus geographically close to the dangers of Japanese air and naval attacks, the Calcutta port remained largely untouched by the spike in wartime activities up until 1942. In a year's time, it was to emerge as the most important port in the newly opened China–Burma–India (CBI) theatre (Figure 2), as a result of Japanese successes that blocked the Allies’ access to ports such as Singapore. The US Army declared it the number one port (in all theatres of war) from October 1944 in terms of cargo discharged. Workers handled 5,795,779,780 pounds of equipment and supplies in just three years.Footnote 21 These included anything from “PX, a toothbrush to heavy equipment, planes, gasoline”, commodities necessary for supplying the troops, building airfields, the construction of the Ledo road, building pipelines, etc.Footnote 22

Figure 2. Bengal and the China–India–Burma theatre, 1942.

Such a massive hike in the traffic at the Port could not have been managed without radical changes in the labour regime, the available technology, and the administration of the port, which, until then, had been under a semi-governmental Port Trust.Footnote 23 As early as October 1942, American Major General Wheeler raised questions about the capability of the port to carry on the war work.Footnote 24 But it was only as a great congestion blocked the port in the winter months of 1943, and the expected doubling of the traffic for the newly set-up operations of the South East Asia Command (S.E.A.C.), that the Joint Transportation Committee decided to implement a series of radical measures.Footnote 25 In administrative terms, a reorganization of the port was carried out in accordance with discussions at the viceregal level.Footnote 26 A Port Directorate was set up in 1944 on the initiative of and under pressure from the US Army. It was established as a coordinating and control body, with authority under the Defence of India rules to issue instructions to the various interests involved in running port, including: the Port Trust's various departments; stevedores; labour contractors; the Indian Jute Mills Associations; the British Army; RAF Movements; the US Army Air Force; US Army Port Transportation; War Shipping Administration (USA); and the Ministry of War Shipping (Britain).Footnote 27 A British director, F.A. Pope, and two American assistant directors, both military men, headed the directorate.Footnote 28 The setting-up of a transnational state body was crucial in shaking up the half-a-century-old labour regime. In a twist of history, the highly regulated labour regime of the post-independence docks was ushered in by the military authorities of the Allies.

In the interwar period, the Port Trust directly employed around 6745 workers: dockers (1745); the “seaman type” or mariners (2000); and in the workshop (3000). The employment of these workers was more regular and they had conditional access to benefits, such as the provident fund, leave, holidays, overtime, and regular working hours. A significant number of railway and clerical workers were also employed, but the numbers are not available for the interwar period.Footnote 29 The majority of dockers, those who did loading and unloading work, were employed through the contractors. Bird & Co., the single largest contractor for those working at the sheds and warehouses, employed between 5000 and 7000 workers. Not all these workers found regular employment, although figures for unemployment levels are unavailable.Footnote 30 The majority of shore dockers were employed on piece-rate basis or in what was known as the khatta system.Footnote 31 The stevedores or Bengali contractors provided skilled loading and unloading labour directly to the shipping companies. These companies employed roughly 15,000 workers who mainly worked on-board the ships, but half of them were unemployed at any point. Not unexpectedly, the dockers were largely casual labour, the sirdar of the Indian industrial scene or his equivalent on the dockyards, docks, and ships – the serang – was ubiquitous in their ranks.Footnote 32

It was through militarization of labour that the first steps towards “steadying labour” were taken. From 1943 onwards, the greater part of the workforce directly employed by the Port Trust and the stevedores was enrolled in Defence of India (DoI) units.Footnote 33 In the next few months, the existing defence units were complemented with specialized military units, as Indian, British, and even African-American soldiers now mingled with the dockworkers in various capacities. Those employed as part of the military and DoI units had relatively better pay scales, rations, and allowances.Footnote 34 The numerical extent of labour militarization can be gauged from the following numbers (from March 1944): 256 officers and 17,422 other ranks enrolled in the Port D of I units, and forty-seven officers and 3,856 other ranks in Calcutta Stevedore Battalion.Footnote 35 The exigencies of the situation and the strained resources resulted in a patchwork of labour regimes running the port, which also broadened horizons of expectations.

Stevedores’ labourers received the most special treatment. The first to be organized in DoI units, they were provided uniforms, as well as accommodation far away from the danger zone of the docklands in Tollygunge and Behala. They travelled “free” to work on the tramways, an unheard-of privilege for Calcutta workers.Footnote 36 They received retention money of Rs. 5, whether or not they were employed during a month and if unemployed for more than ten days, they received a daily payment.Footnote 37 Dockers had demanded an unemployment insurance since the 1920s at least, but this was the first time that the state and the employers conceded.Footnote 38

State intervention became most extensive with the setting up of the Regional Port Directorate. The role of the US Army is striking; the first US ships arrived in 1942 and the US Army took full control of one of the two dock systems – King George's Docks (KGD)Footnote 39 – from March 1944 and managed record shipping turnaround rates, reducing them from eight to three days.Footnote 40 Two port battalions employing 3500 dockers under the supervision of Army personnel worked a three-shift system at KGD.Footnote 41 Having set a high standard of efficiency, the Directorate attempted to improve the coordination of labour supply across the various employers and establish closer control over the labour processes beyond KGD. It was made clear to existing employers that rapid improvements in supervision of workers would have to be made.Footnote 42 For the Traffic department, which was the largest, a scheme for “greater supervision on the Docks and Jetties and better ladders of promotion” was set up.Footnote 43 “Detailed instructions” were outlined for supervisors and officers, aimed at curtailing the personal control exercised by them.Footnote 44 Workers found themselves under the double supervision of “Zone Inspectors” and “Assistant Zone Inspectors”, recruited mainly from the various military companies.Footnote 45 Military personnel wearing armbands with MP written on them are prominent in wartime pictures of the Calcutta port (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The photographer's caption: “GI dock workers of the port companies created order out of chaos at Calcutta's great docks, and thousands of tons of vital war supplies flowed through to China, Burma and India. The MP is on hand to see that the coolies do not pilfer from the rations they are carrying.”

Photographer: Clyde Waddell. Public domain. Available online at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Photographs_of_Calcutta_by_Clyde_Waddell#/media/File:Coolies_carry_rations_at_Calcutta_Docks_in_1945.jpg, accessed on 17 January 2020.

The Directorate also intervened to improve the working conditions. The number of permanent and directly employed workers increased.Footnote 46 It was suggested that methods of wage payments should be changed, for instance granting bonuses for better work and incentives for speeding up.Footnote 47 The issue of increasing wages was pursued consistently. Under their instructions, port workers were included in a governmental scheme that aimed to provide “adequate rations for heavy manual work”. Standardization of wages was another subject under consideration, since the existence of various wages for the same work, not just inside the port but also outside, frequently led to labour disputes.Footnote 48

It is the degree of intervention in the management of Bird & Co., which employed the most casual section of port workforce, that is telling of the impetus for regulation of labour regime during the war. The bad quality of work by casual shore labour was a matter of constant friction between the military authorities, the Port Trust, and Bird & Co. The Directorate, in particular, demanded greater supervision of workers employed by this contractor and payment of “sufficient” wages.Footnote 49 Under such pressures, Bird & Co. switched from piece-rate payments to daily rates for brief periods during the war.Footnote 50 The Port Trust made inroads into the operations of the contractor – directly recruiting labour for the crucial Coal Dock,Footnote 51 and a number of other sites were handed over to the Army units, and it is very probable that they employed the same dockers who had previously worked for the contractor.Footnote 52 In fact, the contractor's dockers’ demands increasingly converged with those directly employed, they too were provided with regular increases in rationing and dearness allowances.Footnote 53 With the end of the war, the Port Trust committed to meeting any extra expenditure by Bird & Co. on minimum wage rates, social security, and housing in anticipation of such statutory changes.Footnote 54 It had become clear that the rolling back of employment conditions as they existed in the interwar period was no longer feasible, even for the most “unskilled” workers.

These ad hoc measures laid the basis for a systematic transformation of the port labour regime, not only in Calcutta but across the Indian ports. Regulation of the employment conditions of dock labour, or decasualization, had been proposed as early as 1931 by the Royal Commission of Labour, but was only implemented in a staggered fashion from the late 1940s onwards. The Dock Labour (Regulation of Employment) Act was legislated in 1948 and the official documentation stated that: “the object of these schemes is to ensure greater regularity of employment for dock workers and to secure an adequate supply of dock workers for the efficient performance of dock work”.Footnote 55 The goals of workers’ welfare and efficiency had already become linked in a number of concrete ways, mostly under the threat of labour flights, shortages, and strikes, as discussed below. The “formal sector” at the ports of the postcolonial state was thus built on the mechanisms and precedents of state interventions inherited from the war years.

As during the war, the stevedores’ labourers were the most impacted by the state policy that sought to regulate dock work. The main features of the regulatory schemes included: employment of inspectors; registration of all workers based on identity cards; pool and monthly workers; and adoption of a three-shift system; many of these aspects had been tried during the war.Footnote 56 All workers were registered by the Dock Labour Board, monthly workers were selected and directly employed by the stevedores, but a greater proportion of workers were directly employed by the Dock Labour Board, which also allocated work to them on a rotational basis.Footnote 57 The decasualization legislations thus were crucial in undermining the role of stevedores as employers of casual labour. By the 1950s, the dockers received: time-rate wages; disappointment money; guaranteed minimum wages; attendance wages; paid sick and casual leave; and a weekly off for monthly workers.Footnote 58

The direct employment of the shore workers employed through the contractors, also known as “departmentalization”, was another major development of the late 1940s in Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.Footnote 59 In Calcutta's case, the contract of Bird & Co., which had provided labour for port work since the late nineteenth century, came to an end in 1948. A majority of shore workers were directly employed through the Port Trust, which now became part of the public sector.Footnote 60 One of the key demands of 1947 strike – that workers’ pay and conditions be in line with the recommendations the Pay Commission set up for the government employees – was won.Footnote 61 The Commission prescribed the implementation of minimum wages for Class IV workers employed by ports in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, and they received a provident fund, gratuity, leave, holidays, weekly off, and paid overtime.Footnote 62 The scope of the Calcutta Port Trust's welfare section had expanded considerably by the early 1950s. Workers were provided with uniforms, canteens, filtered water, schools, a range of sporting facilities (wrestling grounds, facilities for basketball and volleyball, interdepartmental sports and football tournaments), and entertainment options (open air-cinemas, provision of radio sets).Footnote 63 The list of reforms is not comprehensive, as major changes followed the all-India port strike of 1958, but it provides an indication of the transformation towards a highly regulated and formalized labour regime that had been set in motion.

Wartime changes proved to be irreversible, most crucially because of the pressures building up from below. The scaffold of a new labour regime, which was being set up to pacify class struggle, ended up producing an even more fractious set of labour relations. During the war itself, the introduction of ad hoc, piecemeal, but significant changes hardly managed to bind the workers to the employers. The changes managed to avoid major strikes, but the immediate impact of their measures was profoundly unsettling: labour relations were marked by anticipations, expectations, hostility, tensions, and increasingly sharp conflict. The situation at the workplace was compounded by impactful changes outside of it – British defeats overseas, dock bombings, and a raging famine. The following section will focus on changes that help us track the experiences of wartime labouring and tell us how the war incubated a crisis of industrial relations. The analysis is largely based on the records available at the Port Trust archive, and therefore the experiences of those employed directly are discussed in much finer details compared to those of contractors’ workers.

The Militancy of 1942

With the fall of Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya, and then Burma between December 1941 and March 1942, great uncertainty prevailed in the labour world, especially in eastern India, as to what the future held. In Calcutta, the arrival of Burmese refugees, an exodus of nearly a million, the imminence of the Japanese invasion, and hyperinflation, all made the state appear as fragile as Kamtekar has argued.Footnote 64 The “phantom crisis” of the state had enormous implications for workers’ perceptions of the urgency, as well as the possibilities of waging a fight, something that has been overlooked in the scant historiography that connects the Quit India Movement and labour. Traditionally, historians have been concerned with the role, or absence, of workers as participants in the Quit India Movement, especially in Bombay and Calcutta.Footnote 65 While it is probably true that Congress found it difficult to mobilize workers for the nationalist cause per se or even take advantage of the simmering labour discontent in a number of major industrial cities,Footnote 66 it does not necessarily follow that the labour unrest remained unaffected by the turbulent political context. In fact, the case of port workers outlined below suggests that placing the strikes of 1942 in the wider context of war and changing industrial relations will help in understanding their impactful nature.Footnote 67

As early as April 1942, the intelligence section reported of the labour world: “[there is] a general wave of uncertainty, and a disposition to raise petty grievances, restrict production and ask for long leave and advances of pay […] [in] the Calcutta and Asansol industrial areas”.Footnote 68 At the port, through the summer of 1942, the officiating secretary of the CPTEA wrote many letters to the chairman, informing him of the widespread discontent among the workers, “who are ready to go to any extent to have their demands fulfilled for the sake of their very existence [emphasis added]”.Footnote 69 The chairman was presented with an elaborate list of demands and threatened with strikes on multiple occasions.Footnote 70 British defeats in the Far East were reflected in counter-currents to the war effort among workers from the early months of 1942, and these coalesced into threatening collective actions in an opening provided by an episode of nationalist struggle.

To start with, 1942 saw the largest number of workers involved in industrial disputes (772,653) and man-days lost (5,779,965) during the war years.Footnote 71 Workers in Calcutta responded belatedly to the nationalist movement; a fortnight after the Quit India Movement began, an unusually large number of strikes were reported in Indian as well as British and state firms, especially in the engineering works.Footnote 72 At the Port, an unofficial strike broke out in the first week of September 1942.Footnote 73 According to different estimates, between 5000 and 7000 workers went on strike.Footnote 74 They won an immediate rise in dearness allowance and planned another more extensive strike with contracted-out workers from Bird & Co.

The most important unions of port workers had been beheaded before the war as a result of widespread arrests of union leaders. Yet, workers articulated elaborate and novel wartime demands in pursuit of their “life and death struggle for existence”.Footnote 75 They were well aware of changes that employers at the port and outside were willing to make, and of the new welfare measures being debated and legislated in the recently established Labour Department.Footnote 76 Port Trust workers demanded higher dearness allowances, bonuses, and access to provident fund money to enable them to leave in case of danger, as well as the provision of housing outside the danger zone or housing allowances.Footnote 77 Bird & Co. workers raised demands for regularization of employment – abolition of the piece-rate system, introduction of specified daily wages, and wages for “forced idleness”. They also demanded subsidized food at welfare shops, recognition of the union, sick leave, and one month paid leave. Footnote 78 Most significantly, abolition of the Bird & Co. contract was for the first time made a matter of a general strike at the port. Hopes were certainly running high as a liaison was set up with the Indian Seamen's Union to get the seamen to join the strike as well.Footnote 79

Workers maintained considerable control over the strike threat. Although Dipesh Chakrabarty has famously argued about the “feudal” and thus master-like control that the middle-class “outsider” assumed during strikes, owing to their elite status,Footnote 80 Anna Sailer's work on the jute mill general strike of 1929 has questioned the idea of any “absolute” loyalties commanded by the so-called leaders, and has shown that workers appropriated the strike, giving it new demands, geographies, temporality, and possibilities, arguing that the relationship between the trade union/outsider leadership and workers agency was complex, dynamic, and tense.Footnote 81 Wartime strikes present an excellent opportunity to assess the idea that “unknown” elite personalities could easily gain workers’ obedience and underline the role of grass-roots activists. The detailed nature of demands already shows the involvement of ordinary workers. The strike threat at the docks was real enough for a number of nationalist politicians to jump at the opportunity to form the official leadership of the second strike through a Joint Committee, despite their lack of experience of labour politics at the port or in the city.Footnote 82 Over the course of the next two months, the Joint Committee handled the task of negotiations, but the strike committee, through its extended networks, held the fate of the strike in its hands. Local worker-activists, with several years of experience, revived existing union structures, activated and expanded old networks, including contacting trade union leaders banned from entering Calcutta, organized basti meetings in dock neighbourhoods, formulated demand charters, and drafted novel propaganda leaflets.

Identifying “the brother workers of Port commissioners and Bird & Co.” as its audience, the strike committee stated in a remarkable leaflet:

We, the workers of the Port Trust and Dock are carrying on our daily work in this danger zone ignoring the fear of Japanese bombardment. We are doing so for the maintenance of our family [emphasis added] in these hard days when the price of food […] You have seen that through negotiation no demands can be met […] We are all prepared to go on strike and we are making the necessary arrangements for it. We are waiting for the decision of the strike committee formed by the representatives of all the sections [emphasis added]. We must not let the chairman, Port Trust or the Bird & Co. know when and at what moment we are going to declare strike. The strike committee is the only favourable instrument in our hand. We shall declare strike at the most unguarded moment of the employers and at the cost of life to go on strike. You must not read leaflets given by outsiders […] We should abide by the decision of the volunteers and section representatives. We must go on strike until all our demands are fulfilled […] If the authority agrees to concede to our demands they should do that in a public meeting of the workers […] We must not flout the decision of the strike committee at anybody's provocation.Footnote 83

The leaflet was published in defiance of Humayun Kabir, of the Joint Committee, who suggested in a meeting of about fifteen workers, including Parmananda, Sadananda, and the union secretary of non-worker background Radheyshyam Banerjee, “maintain[ing] peace”, after he had received a promise of settlement from the then labour member of the Viceroy's Council, Dr B.R. Ambedkar. The combative leaflet is suggestive not only of the intensity of ferment but the maintenance of interwar organizational structures and networks, probably underground, into the war. The section committees that were organized in the late 1930s as part of shop-floor units of the CPTEAFootnote 84 now formed the basis of a strike committee, which offered workers an opportunity for grass-roots representation and a clandestine leadership. This strike committee is not mentioned in any of the official correspondences, apart from the leaflet itself, but its presence can be detected in the organized nature of the resistance. After the first strike, Port Trust workers sent a flood of petitions with hundreds of thumbprint impressions to the chairman, demanding pay for the strike days.Footnote 85 Such petitions could not have been organized without militants who were known among workers and who were willing to take the risk of appearing as saboteurs. The intelligence records reveal that sectional leaders played a prominent role in meetings in workers’ neighbourhoods in the docklands, which attracted hundreds at a time, including from the nearby factories.Footnote 86 In fact, the politicians of the Joint Committee revealed the strength of the grass-roots organization when one of them admitted that he would not be obeyed on the question of giving up the strike, and the Chairman had to face fifty-four worker delegates.Footnote 87 The strike preparations, even with the top union leadership previously banned from entering Calcutta, made Governor Herbert hesitant to use the members of a military corps, the Pioneer Battalion, in the event of the strike, as he suspected “strong picketing which may lead to clashes between the employees and the military”.Footnote 88

Lastly, the authors of the leaflet articulated that workers were enduring great hardships due to the war, not for reasons of loyalty but for their own survival. The strike committee was propagating an attitude of indifference to the war, arguing this with a great moral force in times of ferment, suggesting that the state was unable to eliminate antagonistic and oppositional stances halfway into the war. This is worth noting as trade union language at the port, across the political spectrum, would become tenaciously pro-war and conciliatory in a matter of a few months, with even small petitions being framed in such terms.

Workers’ acquiescence was gained by early December, which can be explained by new arrests, Chief Minister Fazlul Huq's intervention, a recommendation of the strike for adjudication, and a certain loss of momentum.Footnote 89 Still, 1942 made clear the repercussions of British wartime defeats for an Indian workplace, as it was to be the most eventful year in terms of collective action for the duration of the war. The Quit India Movement, above all, was an opportunity seized by port workers to present their own elaborate demands. Nationalist politicians rushed to assume leadership, yet a small number of worker activists, through their clandestine strike committee, maintained control over the brewing strike. They self-consciously moulded a confrontation of considerable significance, which the employers and state authorities tolerated for over two months. This was how they established their presence in front of the employers, anticipating and strengthening the impetus for wide-ranging reforms of the casual-labour regime. The workers carried the legacy of the experiences accumulated in the shadows of wartime repression with them into the post-war period.

The Despair of 1943

1942 saw a powerful moment of labour militancy, but it came to an end with the dock bombings. The spectre of death by bombing was not the only one confronting the workers; starvation and famine lurked in their midst with the onset of famine in 1943, the year ended with another, deadlier episode of bombings. A period of despair seemed to set in, which another historian has described as the “year of the corpse”.Footnote 90 Anxieties about death strained workers’ relationships with their employers, deepening hostilities, and delegitimizing both the employers and the state.

It was commonly believed that the docks were one of the primary targets of the Japanese government. And when the first major series of bombings took place in the last week of December 1942, tens of thousands of workers left the docklands.Footnote 91 The mass flight of workers, deemed as “essential workers” for the running of a major wartime port, was indicative of workers’ indifference to the war effort, as well as the authorities’ lack of preparations. Several petitions sent after the workers’ return, demanding restoration of their past conditions of work,Footnote 92 articulated a great sense of uncertainty and danger as workers’ reasons for running away.Footnote 93 An unusual and detailed petition sent by two different sections of workers (through the CPTEA) – the Jetty coolies and the railway workers – allows us to look beyond the great fear that gripped workers.Footnote 94 For hundreds who signed the petition, the employers were responsible for their sudden departure, as they made adequately clear.

Workers explained that air raids were something completely new for them and that they, “the poor and illiterate workers had any [no] concrete idea about the character [of] an air raid”.Footnote 95 Still, they had not been provided with “any scope or real training as to how to defend” themselves. They had been demanding better shelters and housing since the panic of December 1941, but despite their many appeals, the administration did nothing except build a few shelters.Footnote 96 The workers held the administration responsible for not preparing for the protection of workers’ lives against a foreseen danger. They further emphasized the culpability and the incapability of the administration, pointing out that they did not even leave immediately after the air raids started. They said, even if only to make their case, that they remained in place even as the city was deserted through the exodus of “general workers of different mills and the factories”, and even when they “in horror witnessed casualties and severity of air-raids before their eyes”.Footnote 97 Furthermore, they sent a deputation to the chairman to appeal that they be allowed to “live in the ground floor of the high storied buildings (Tea Warehouses) within the Port area”. They also approached the sectional officers, who did not know what to do themselves, and suggested that they find a way to save their lives themselves. Their only hope was to leave, as is evident from the petition, which concluded: “it was natural [emphasis added] that our panic-stricken and affected workers had to leave Calcutta”.Footnote 98

Not much changed in terms of provision of air-raid precautions for workers when the second major bombing took place a year later, in December 1943. A series of daylight air raids continued for two days and directly targeted the docks, leading to a far greater number of injuries and deaths.Footnote 99 The coal berths of the docks and some of the “coolie lines” were severely hit, and burnt for hours on end. The damage was not limited to the docks, and spread through the surrounding factories, shops, and residencies.Footnote 100 This time, although the casualties from the bombings were great, there was no accurate information on the number of dead. The docks were reportedly rife with rumours. The number of dead was claimed to be anywhere between 3000 and 4000,Footnote 101 in the context of obviously misleading official information.Footnote 102 The details of these rumours are highly interesting from the point of view of understanding workers’ perceptions of the official response to the bombings. We have access to them through a revolutionary communist leaflet.Footnote 103 In order to make the required political points, the leaflet relied on giving voice to the horrors, the resentments and the predicaments of workers. One of the unusually palpable passages of the leaflet, in its gory description of the brutality of the actions of authorities, seems to have relied on a number of such rumours.

It was stated in the leaflet:

[T]he white people […] took shelter inside big and strong buildings and houses. The military police saved their lives by taking cover under the brick and stone-built shelters. But there was not a space for the unfortunate workers […] Being bombed, 5,000 workers were scattered on the Kidderpore docks, in the Port, the jetties, the factories and in and round the demolished Tinned, Tyled, Khola sheds like cattle with their limbs separated […] They threw away the shattered bodies of about 3,000 workers in the Ganges. They shot 1,500 half-dead workers to death and buried them under dock water and sent about 500 workers only to the different hospitals of Calcutta.Footnote 104

In this case, the rumours reflected a strong sense among sections of workers that their employers and government officials were capable of being accomplices in an enormous tragedy in which thousands had died. In addition, they revealed a perception of indifference and callousness on the part of the authorities to the point of not differentiating between the dead and the dying. If it was too inconvenient administratively to deal with the dying, they had to join the dead. Workers repeatedly insinuated and, after the end of the war, openly remarked, in letters to the management and in union leaflets, that the authorities had failed to provide when Japanese bombs “stained the soil of this city with the blood of brother workers”.Footnote 105

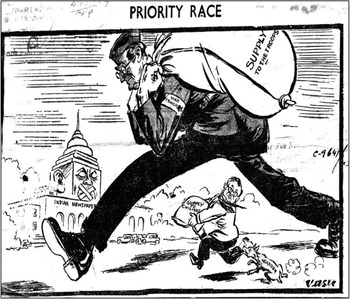

Workers were terrified of the bombs, but they returned in a matter of couple of months. After all, they were assured not only a wage at the workplace, but also food rations at concessional rates, at a time when famine engulfed large parts of Bengal and Bihar. The authorities had realized as early as 1942 that food rations will be crucial for keeping workers at work and this they emphasized repeatedly; rations were thus organized and assured as the most crucial new incentives. A larger proportion of port workers received their rations through the military, as they were part of the Defence of India units.Footnote 106 Food rations hardly evoked gratitude, they became a site of pervasive low-key, everyday contestations carried through petitions and occasional strikes (Figure 4). More than a year into rationing, union activists reportedly complained of “worm-eaten” and “bitter in taste” rice and atta (wheat flour). The chairman admitted that this was the case sometimes.Footnote 107 He also noted that the rationed food continued to be “very poor” and at times was “even unfit for human consumption”.Footnote 108

Figure 4. A contemporary newspaper cartoon depicting the discriminatory rationing practices of the colonial government.

Benthall Papers, Box no. 18, newspaper cuttings. Centre for South Asian Studies, Cambridge, UK.

Food was the subject of the widest variety and a large number of petitions and letters to the management after the food crisis worsened in 1943. Petitioners frequently, but not always, adopted a pro-war and pro-employer idiom, reflective of the CPI's influence. Even so, these petitions are windows into everyday experiences at work and, claim-making and negotiations beyond major events. A number of historians have argued that petitions were generally coded in a language of supplication expected by the colonial authorities, but it is possible to probe the narrative strategies used by the authors to gain access to more textured accounts of perspectives of the petitioners.Footnote 109 One such petition was written by those who worked at the C.D. Barge no. 3 and Marine Point:Footnote 110

[…] food stuff […] is unsuitable and now is already telling on our health. As such our efficiency for work tends unperceptibly [sic] to deteriorate and we apprehend it will ultimately result in the loss [emphasis added] of the company for which we are so anxious to offer our loyal and sincere service.

[…]

We further beg most humbly that if under present circumstances the company may not manage to provide us with the desired quality of materials at the existing rates, we shall try our utmost to pay a higher one for the sake of our health and above all, the interest of the company under which we serve […]

The exaggerated and repeated claim that the petitioners cared “above all” for the interests of the company casts doubts on their intentions. At the same time, it is also clear that workers decided to invoke the logic of efficiency to support their demands. Many similar petitions showed a remarkable consciousness among workers of the importance of their labour, as well as the seepage of a certain productivism preached as part of wartime propaganda as well as by the CPI. In another petition, workers argued:

Yet we are lingering to the work [sic] of our Port on which depends the fate of the country and the future of the mankind, but the nature will not forsake us – we are languishing and day by day getting weak. We must not indulge in this condition. We know that to indulge in this means to indulge in the slowdown of and obstruction of the vital work of our port, which will hamper the defence of our sacred mother-land and the victory of the democratic forces.

Such petitions, even as they voiced commitment and loyalty to the employers, if not the Allies, were polyvalent. The first petition quoted above presented a veiled threat, for instance. In not so many words, workers threatened their bosses with the losses that would “ultimately result” from the ongoing “unperceptible” deterioration in work. The petition is suggestive of go-slow as a tactic being used by workers during the war.

As previously said, petitions were not always coded in loyalist idioms, sometimes they were pointed and directly addressed the issue. Employers had conceded food rations as essential incentives, workers continually pushed the boundaries of what these should consist of. The firemen and coal trimmers of Dredger Gunga compared their rations to the seamen, who were “better fed” even though their “working conditions are far lighter”. They argued that their rations should be commensurate with the amount of work they performed, and, as they did more work, they deserved more rations.Footnote 111 They threatened their reluctant resignation and demanded an “early reply”.

Workers also demanded provision in accordance with their cultural requirements and preferences, for instance, higher rations for the month of Ramzaan. The East Bengali workers refused to accept reductions in their rice rations.Footnote 112 They sent a petition with 200 thumbprint impressions when rice rations were replaced with atta due to non-availability of rice.Footnote 113 They explained: “we belong to Bengal and are habituated of rice food [sic] […] atta will never suit our health for the reason we have been attacked from various kinds of diseases [sic]”.Footnote 114 Writing half a century after the events, Jolly Mohan Kaul, who had been a communist activist at the port, recalled in his memoir how workers managed a reintroduction of rice rations: “there was a lightning strike by the entire marine staff that spread from Budge Budge to Hooghly Point”.Footnote 115 This sole record of the strike is valuable, as it points to the hidden transcripts of wartime resistance that surfaced in certain moments, took local communists by surprise, and which remain missing in the official record. Just like the strikes of 1942, this one seems to have been organized at the workers’ own initiative.

On the whole, the employers and the state managed to keep workers labouring with rations that were hardly sufficient, but they aroused great indignation, which workers repeatedly registered in terms such as: “strained of inanition”; “our health will breakdown”; “we will be reduced to dead”.Footnote 116 Even in the depths of despair, hundreds of workers unhesitatingly, frequently, and collectively demanded food as compensation for their labour, making new and urgent claims on their employers and the state. These were made in largely accommodationist petitions and frequently coded in loyalist rhetoric. Sometimes, the petitions carried militant undertones and held veiled threats of withdrawal of labour.

Shop-Floor Conflict

So far, a troubled workplace has been sketched through events that were extraneous to it but which nevertheless heavily impinged on it. It is even possible to directly trace the impact of changing work organization on workers’ relationship with the employers. The Directorate had been set up to aid an intensive exploitation of labour through a centralized, tightened, and rational control. This was not easily done in practice, however. The Directorate, partly due to the abruptness and rapidity of changes, sometimes undermined the various layers of the existing management and deepened tensions on the shop floor. Dissonances between management practices and state policy resulted in opportunities for workers to start intervening in the authority of the management over the labour processes. Although workers’ control did not emerge as a trade-union demand, it is reasonable to suggest that sections of workers were conscious of the power they wielded on the shop floor. For the employers, this changing balance of power was far more threatening than demands for food rations or wages. Indiscipline was bosses’ foremost complaint in the post-war period; indeed, discipline had already become difficult to impose during the war as sections of workers acquired new confidence.

It is illuminating to consider the growing assertiveness of crane drivers, at times along with workers of other occupations, over their supervisors and managers at the height of wartime activities. Crane workers/drivers, and khalasis, were one of the most vital and skilled sections of the workforce. As war imports rose dramatically in 1944, cranes remained in “universal shortage”,Footnote 117 as did the workers who operated them. They also learnt to operate various kinds of technologically advanced cranes.Footnote 118 Crane drivers were on the highest pay scale among the manual workers, paid double the wage of lowest paid ones – a porter or a crane khalasi, and even earned better than some clerical workers.Footnote 119 The crane driver was set apart from rest of the workers, but he started his journey as a khalasi.Footnote 120 The growing importance of crane drivers did not strengthen their affinity with the local management. On the contrary, they gained a reputation for their “recalcitrance”.Footnote 121 So much so that Crane Inspectors, many of whom were British soldiers, were specially employed and trained to keep them “up to the mark”.Footnote 122

In 1944, the busiest year of the war, letters from workers at the Jetty Engine House became unusually expressive about the mistreatment by senior managers, unfair dismissals, lack of promotions, and disruptive activities of dalals (stooges).Footnote 123 The crane workers, along with the staff of Jetty Engine House, even forced the removal of the Engineer-in-Chief, Mr Ross.Footnote 124 Such dismissals of senior management based on complaints by workers were rare, especially since it could encourage further insubordination. This is precisely what happened; the relations between the local managerial staff and workers remained tense, and the latter did not shy away from complaining against the new Engineer-in-Chief, Mr Hogan.

Moreover, workers continued to be critical of the arrangement of work. They reported that their complaints about defects in cranes were often not taken seriously, and sometimes they were even abused for doing so.Footnote 125 One of their petitions, which had 117 thumbprint impressions, explicitly stated: “We are drawing your attention to the following defects of arrangement of work [emphasis added] for necessary readjustment.”Footnote 126 They stated that they were supposed to work until 6 pm, but the water pressure was sometimes stopped before. In an agitated tone, they explained how such a sudden stoppage in supply of water is a dangerous operation. Since they had no indication of time, they also demanded that they be provided with it.

Such assertions over the labour process could translate into workers posing direct challenges to their local supervisors and even senior managers, which, given the risks that were involved in such individual acts of resistance, should be considered as one step further from collective petitions or complaints. While a crane driver called Balaram Ahir was unloading some carts, a supercargo ordered him to load lorries for the Director General Military Personnel (DGMP).Footnote 127 He dared to ask for an “Order Sheet”, and when the supercargo did not give him any piece of paper, he refused to obey the order.Footnote 128 The angry supercargo called the Engineer-in-Chief, Mr Hogan, who, in turn, told Ahir to strictly follow the supercargo's orders. In the words of the union secretary, Ahir argued that he “would have carried out the order long before if he would receive any any [sic] such order [written] beforehand”.Footnote 129 The Engineer asked Ahir to get down from the crane and took him to his office.Footnote 130 He also called a nearby MP, and Ahir was threatened with jail. Ahir, meanwhile, submitted a complaint against the Engineer via the union to the Welfare Office.Footnote 131 The Welfare Officer was aware of the unrest among workers in the Jetty Engine House and especially their antipathy towards Mr Hogan. He decided to frame this case as that of “labouring under misapprehension”, and concluded in his enquiry that this was not “a case of deliberately flouting an order”.Footnote 132

Ahir might have been confused about the rule, but what is less clear is why he stuck to his version of the rule even when he was confronted by the Engineer-in-Chief. When told to follow orders without clarification of the rule, Ahir defied his boss. Certainly, he was not afraid of directly challenging the authority of his superiors. And he did so in front of a large group of workers, adding to the prevailing “unrestness [sic]” among them.Footnote 133

The case involved loading of military goods and was discussed at the highest levels of management. The Chief Mechanical Engineer contemptuously argued that such written orders were “unnecessary and useless”, since the crane drivers could not read English.Footnote 134 Moreover, he argued that such an order “serves to give a recalcitrant crane driver an opportunity to make trouble [emphasis added]”, revealing the anxieties as well as the reluctance even on the part of some in the top management with regards the new rules.Footnote 135 But the Docks Manager disagreed and argued that the case showed that crane drivers “are not ignorant of the procedure and they actually do recognise and understand the form”.Footnote 136 Verbal orders would no longer suffice and a form serving as written proof for “Crane Man's authority in use of the crane” was made a requirement.Footnote 137 In fact, the form symbolized the crane drivers’ changing position vis-à-vis “the authorities”. The observation of the Docks Manager reveals that the crane drivers valued this piece of paper, which gave them a limited authority over the operation of the crane, and certain immunity from the orders and authority of their superiors. Finally, Ahir won his case against a senior manager despite his public disobedience and an important breach of discipline. At the same time, the incident is reflective of the audacity with which some of the workers were confronting their managers.

The crane men were certainly unusual in terms of the skills and training that their work required, as well as the strategic importance of their work, and no doubt they were thus relatively more conscious of their value, their place and power on the shop floor. Yet, in the circumstances that the war had created, their attitudes, modes, and forms of resistance were shared with other sections of workers. Cases with subjects such as “discipline”, “insubordination”, and “insolence” multiplied in the correspondences within the management and between the managers and the union leadership, from the end of 1945. For instance, Amir Hossain interrupted Mr Fountaine as he was instructing a Serang of the Tug Active as to the best way of speeding up the work. He was called to a senior manager's office and initially refused to come on the grounds that he was off duty.Footnote 138

To be sure, the situation was different from what has been described in the immediate aftermath of 1937 general strikes in the jute mills in Calcutta and textile mills in Kanpur, where mill-level workers’ committees became assertive and undermined the mill authority, especially that of the sirdar and the mistry.Footnote 139 The 1940s formed a prolonged period of simmering tensions in the workplace and with direct implications for the long-term structure of industrial relations. For the case of Bombay, Chandavarkar has shown how the mill “jobber” came under untenable pressures for a number of reasons – including the hostility of workers, and was replaced by the “employment exchanges” in the 1950s.Footnote 140 The wrath of port workers was not limited to the immediate supervisor but extended to higher levels of the management, which was reflected in a number of complaints about the “insubordination” of workers. Just as the war came to an end, workers’ participation in stoppages, strikes, and demonstrations multiplied.Footnote 141 The 1947 strike, for the first time, involved all sections of Port Trust workers and lasted for three months; simultaneously, strikes occurred among the contractors’ dockers, and the watch and ward guards went on a strike in 1948. In fact, one of the most striking aspects of the 1947 port strike, was the number of incidents in which the officers (including the Indian welfare officer), senior managers, and engineers were physically attacked at the workplace.Footnote 142

The case of the port suggests that the relationship between workers and the management, more generally, had become very strained. Skilled workers, who could be expected to be more loyal, emerged as “recalcitrant” and claimed their control over labour processes and on the shop floor. Such steps may not have been expressed in trade union bulletins, but they remind us of developments in class struggle in the technically advanced industries of post-World-War-I Britain – engineering and railways, from wherein the demands for workers’ control first found wider resonance.Footnote 143 It is important to recognize that the post-war period raised difficulties for the employers for the subordination of workers, at various levels and, crucially, at the point of production. A crisis of authority at that level of the shop floor marked most visibly the cracking open of the interwar labour regime, which could no longer remain as it had been. Considerable anxiety was palpable in the ranks of the employers. In his presidential address to the first meeting after Independence of the Associated Chambers of Commerce in Calcutta, Mr Cumberbatch complained bitterly to Nehru about discipline, the biggest problem of all: “without discipline, control is ineffective, whether it be control by government through the forces of law and order or control of efficiency in a mill or factory […]”.Footnote 144

Conclusion

There is a recent recognition in scholarship of the uneven yet worldwide impact of World War II on state, society, and politics. The role of global wars in reshaping of society in South Asia is only beginning to be studied.Footnote 145 This article shows that a focus on dock workers opens new perspectives on the dramatic and direct impacts of the war on the colonial and postcolonial labour relations, the (post)colonial state, the processes of decolonization, and the politics of labour. It has made clear how the upheavals of the war pushed the “social question” to the forefront and brought the state into the lives of labour in the colonial world, in ways more familiar in the history of twentieth-century Europe.

The war prepared a new labour regime, in employers’ chambers, government offices, and in the newly set up Labour Department, but, crucially, also in the workplace and on the shop floor. Focusing on the microhistory of the Calcutta port allows us to see the complex historical processes that generated an unprecedented impetus for the transformation of labour regime – from one based on casual labour and contractors, to one of the most formalized and state-regulated workplaces in the post-independent India, with significant welfare provisions.

There was nothing smooth or inevitable about this war-induced transition, and it had not been planned as such. Since the late 1930s, the employers and the state had anticipated that the labour question would be the key to the war, but they only introduced ad hoc, piecemeal, even if significant changes under wartime exigencies. The account of workers’ experiences as presented in this article shows us how the measures designed for stabilization and efficiency proved to be profoundly unsettling in the context of dramatic wartime events that pervaded the workplace. In the shadows of the war, workers and employers experienced a major shift in the balance of forces. At the most hopeful moment, workers staged a major strike threat, backing elaborate wartime demands and those relating to decasualization of labour. In a matter of months, however, faced with bombings, they took flight and returned to work on the barest of food rations. This was clear evidence of their vulnerability and precarity, but even in the depths of despair, many held the employers responsible. They expressed their indignation, through largely accommodationist food-related petitions as claims for compensation of labour. Towards the end of the war, a crisis of authority emerged on the shop floor, as skilled workers, especially crane workers, confronted the management with rising self-confidence. Wartime hostility charged the hopeful atmosphere on the eve of independence, major strikes involved all categories of port workers between 1945 and 1948, involving previously unseen violence, but these still did not take the form of city-wide general strikes. Employers and the state had feared and expected this crisis of industrial relations, and much worse. With hurried and bold steps, they extended and systematized many of the wartime measures. A transformation of the docks’ casual-labour regime was the price that they paid for winning an “industrial truce”, as it was appropriately called,Footnote 146 by the end of the decade.