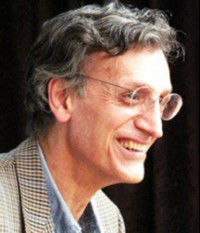

Our colleague Chahryar Adle, emeritus-senior researcher at the CNRS, passed away in Paris on Sunday 21 June 2015, at the age of seventy-one. He was born in Tehran on 3 February 1944 to a renowned family. On his mother’s side, he was a descendant of Bāyazid Bastāmi (804‒74), the famous Iranian Sufi of the ninth century, a lineage that carried a special honorific status at the royal court from the Safavids to the Qājārs. A descendant of this lineage, Qāsem Khān Vāli, son of Dūst-ʿAli Khān Moʻayyer al-Mamālek, was first a page at the court of Nāser al-Din Shāh (r. 1848‒96), but rapidly climbed the ranks and occupied several positions such as Iran’s plenipotentiary Minister in St. Petersburg (1857‒61) and the provincial governor of Gilān (1862‒69) and of Fārs (1871‒72). A connoisseur and gourmet, Qāsem Khān is known as the creator of the famous Iranian dish mirzā qāsemi, which also bears his name (this dish, made with smoked eggplant and garlic, is considered a specialty of northern Iran). Qāsem Khān had two sons, one of whom, ʿAli Khān Vāli, was appointed governor of Marāgha in 1879. He loved daguerreotype and left two exquisite albums with photos that are kept in the Golestān Palace in Tehran. ʿAli Khān Vāli was the father of Qāsem Khān Sardār Homāyūn who studied at the famous French military academy of Saint-Cyr (in 1893‒96). Returning to Iran, Qāsem Khān established in Tabriz the first municipality of Iran and filled the post of mayor. According to the French consul at Tabriz, Alphonse Nicolas, in 1902, Qāsem Khān was “a true European amidst the Persians,” who installed telephones and electricity in Tabriz for the first time. This initiative coincided with the birth of one of Qāsem Khān’s daughters, Homā, on whom Mozaffar al-Din Shāh (r. 1896‒1907) bestowed the title Ziyā’ al-Molūk (lit. “Light of Sovereigns”). Forty years later, following her marriage to her maternal cousin, Ahmad-Hoseyn ʿAdl (Adle), she gave birth to Chahryar. Chahryar’s father also came from an influential family of Tabriz. During the Ilkhānid period (1256‒1355), the ʿAdl family held the post of Qāzi al-Qozzāt (supreme judge) of Tabriz, hence their title of ʿAdl al-Molk (lit. “Justice of the Realm”) which they carried until the beginning of the twentieth century. These men of the cloth wore black turbans as a sign of their descent from the Imam Hoseyn, and hence the Prophet. Over the centuries these “Hoseyni Shām-Q˙āzāni” sayyeds became increasingly involved in commercial activity and thus under the Qājārs they became important merchants who were not indifferent to the political affairs of the country. Chahryar’s great-grandfather Hājj Sayyed Hasan Shām-Q˙āzāni ʿAdl al-Molk (1841‒1918) was influential among the constitutionalists of Tabriz. In 1906, as representative of the nobility, he was a member of the committee supervising the elections (anjoman-e nezārat bar entekhābāt) of the deputies from Azerbaijan for the first Majles. His descendants, who took the family name of ʿAdl (Adle) (lit. “Justice”), were mostly graduates from French universities and played an important cultural and political role during the late Qājār period and under the Pahlavis. Sayyed Mostafā ʿAdl Mansūr al-Saltana, one of the first law professors in Iran, also served, among other positions, as the Iranian representative at the UN; Habib ʿAdl, professor of medicine, brought the first X-ray machine to Iran; Yahyā ʿAdl, a famous surgeon, had an interest in politics and served as a member of the Senate for a number of years; and finally Ahmad-Hoseyn ʿAdl, Chahryar’s father, was several times minister of agriculture under the Pahlavis and founded Tehran University’s Agricultural School in Karaj, northwest of Tehran. This school had a significant impact on the modernization of Iranian agriculture.

Chahryar, the youngest son of the family, grew up in Tehran and after attending the elementary school was sent to France in 1959 to complete his high school and university education. After receiving his high school diploma (Baccalauréat), he followed his mother’s wishes and studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts (School for Fine Arts) in Paris. Homāyūn, one of his brothers, had studied there and had just died together with their father in a car accident between Isfahan and Tehran (in 1963). His mother had wished that Chahryar would become an architect and accomplish his late brother's projects. However, Charhyar was more impassioned by history and archaeology than by architecture. Thus after a few years, without having graduated, he left architecture to study art history, Islamic art history and Oriental archaeology at the École du Louvre. At the same time he embarked on Iranian studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE) in Paris where, in 1970, under the guidance of Jean Aubin, he wrote a dissertation on “Une région frontalière iranienne, le Dâmq˙ân, de la mort de Tamerlan (807/1405) à l’avènement de Šâh ‘Abbâs le Grand (995/1587)” (History of Damghan from the death of Tamerlane to the reign of Shah Abbas). A brilliant student of Jean Aubin, for several years Chahryar Adle was asked to teach Iranian history at the École des Langues Orientales (School of Oriental Languages) in place of his professor. In 1973 he was hired by the CNRS. His doctoral thesis, completed under Jean Aubin’s supervision, was submitted to the Sorbonne nouvelle and received unanimous praise. It was a critical edition with an annotated translation and commentary of Fotūhāt-e Homāyūn (Royal victories), written by Nezām al-Din ʿAli Shirazi (1551‒1602), known as Siyāqi-Nezām, a Safavid manuscript that recounts events related to Shāh ʿAbbās I in Iran and Turkestan.

As a researcher at the CNRS, Chahryar Adle collaborated directly with the Center for Archaeological Research in Iran and with the Iranian Ministry of Art and Culture under the Pahlavi regime. This collaboration did not end with the Islamic Revolution, an event that Chahryar understood better than many of his colleagues, as could be seen from his contribution to the conference, La compréhension de leur passé par les musulmans d’aujourd’hui (The understanding of their past by today’s Muslims), held at the Collège de France in March 1979 and subsequently published in 1981.

After 1979, Chahryar Adle was quick to establish good contacts with senior officials at Iran’s Organization of Cultural Heritage (Sāzemān-e Mirāth-e Farhangi, an institution created after 1979). Therefore, during the first months after the Revolution, at the request of the Iranian government, he went to Cairo at his own expense to present the case of three Iranian archaeological and historical sites (at Persepolis, Choq˙āzanbil and the Naqsh-e Jahān square in Isfahan) for registration on UNESCO’s world heritage list. Thanks to his efforts, this initiative that had been started shortly prior to the Revolution was successfully concluded and thus helped to protect these sites that might have been threatened not only by revolutionary excesses, but also by Iraqi bombs and missiles during the Iran‒Iraq War (1980‒88).

Although the Islamic Revolution interrupted the archaeological activities of non-Iranian archaeologists in Iran, thanks to his contacts with the Organization of Cultural Heritage Chahryar Adle could not only continue his archaeological excavations at Rey and Dāmq˙ān, which had started shortly before the Revolution, but also began work on a new site at Bastām and surveyed the architecture of that city. By using photogrammetry and precise survey methods he was able to highlight the history of the city of Dämghän and show that its architecture goes back to the eighth century CE.

In the 1990s he became more interested in the restoration of Iran’s heritage than in systematic archaeological digs. The socio-political events that occurred in the 1990s and 2000s on the Iranian plateau increasingly encouraged him toward that path. In Afghanistan, after the takeover by the Tālebān and the threat to the Buddha statues at Bāmiyān, he did his utmost at UNESCO to have the site registered on the world heritage list; but it was in vain. However, this setback did not stop him from concentrating his efforts to preserve monuments and buildings of the Islamic period in the border area between Iran and Afghanistan (such as the mosque of Zūzan), and likewise in the city of Herat. Having become a member of the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), Chahryar Adle worked on the Islamic buildings in Balkh during his final years.

After the earthquake of 26 December 2003 that struck the city of Bam in southeast Iran, and severely damaged its fifth century BC citadel, Chahryar Adle, heading the FICOB (Franco-Iranian Cartographic Operations in Bam), focused on the archaeological study, restoration and protection of this site which had been registered on the UNESCO’s endangered heritage list. For him, Iranian civilization did not stop at Iran’s current borders. According to him, the entire Iranian plateau had to be taken into account and for this reason he studied religious buildings and archaeological sites in the Caucasus as well as in Central Asia. This multicultural and multi-disciplinary orientation had made him a valued contributor to UNESCO’s scientific projects concerning ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), World Heritage Center, and the history of Central Asia. In 1993, Chahryar Adle became Iran’s representative at the international scientific committee of this latter project from which an important series of six volumes were co-edited by him; the fifth volume was published in 2003. Since that year he also became the chairman-elect of the international scientific committee for the history of Central Asia. This direct and generous collaboration earned him four honors bestowed by UNESCO: the Aristotle medal (1996), the Avicenna medal (2003), the UNESCO sixtieth anniversary medal (2005) and finally the Five Continents medal (2009).

Chahryar Adle was a multidisciplinary researcher. In addition to history and archaeology, his two fields of choice, he was also a renowned expert of Persian miniatures. This allowed him to play a major role in the return of the illustrated Shāhnāma-ye Tahmāsbi manuscript to Iran, exchanged on 27 July 1992 for a painting by Willem de Kooning that the Iranian government gave to the heirs of the collector Arthur A. Houghton (1906‒90), who had owned this Shāhnāma.

The history of photography that began in Iran in the nineteenth century with daguerreotypes was another field in which Chahryar Adle was an uncontested expert. His writings, notably his article in Studia Iranica, co-authored with Yahya Zoka, remain standard works. From daguerreotype he passed to film and the history of cinema in Iran, when in 1983, in the Golestān Palace, he found rolls of film shot at the beginning of the twentieth century at Mozaffar al-Din Shāh’s court. Thanks to his contacts with the CNC (Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image animée) in France he was able to restore these films and thus preserve part of the cinematographic history of Iran.

Chahryar Adle, our friend and colleague, was a man of taste. Despite a car accident in the 1970s in the United States that forced him to eat no more than one meal per day, he appreciated good food and knew Iranian gastronomy very well. Many can attest to his charm, his kindness, his generosity and his total readiness to help. A friend of France and the French, he played an important role in the strengthening of bilateral cultural and academic relations after the Iranian Revolution in spite of strong tensions. In particular, he sponsored the granting of university scholarships to Iranian researchers in history and archaeology. Patriotic in spirit, he always refused to take double nationality, although his work at the CNRS would have allowed him to obtain it easily and quickly. This did not stop him from being appreciative of France, which had received him over the years.

Chahryar Adle’s heart attack on Father’s Day 2015 in France deprived his six-year-old son, Homāyūn, of a loving father and his wife, Maryam Pir, of an affectionate husband, and finally his colleagues of a great scholar who labored his entire life for Persian civilization and the protection of the Iranian heritage. His numerous publications, written in French, English and Persian, bear witness to the extent of his research (see hereunder a list of Chahryar Adle’s publications, which he had prepared shortly before his passing).

C. Adle List of Publications Footnote *

Books:

1- Ecriture de l’Union, Reflets du temps des troubles, Œuvres picturales (1083‒1124/1673‒1712) de Hâji Mohammad, Paris 1980.

2- Art et Société dans le Monde iranien (ed. by Ch. Adle), Institut Français d’iranologie de Téhéran, Edition Recherche sur les Civilisations, Synthèse no. 9, Paris 1982.

2bis- Persian translation: Honar va jâmeʻe dar Jahâhân-e Irâni, version persane et actualisée de l’Art et Société dans le Monde iranien, Téhéran, 1378/2000.

3- Les Ottomans, les Safavides et la Géorgie, 1514‒1524, co-authored with J-L. Bacqué-Grammont, Istanbul, 1991.

4- Bicentenaire de Téhéran, coedited with B. Hourcade, IFRI/ADPF, Paris, 1993.

4bis- Persian translation: Tehrân pâytaxt-e devist sâleh, ed. C. Adle & B. Hourcade, IFRI/Sâzemân-e mošâver-e fanni va mohandesi-ye Šahr-e Tehrân, Tehrân, 1375/1997.

5- History of Civilization of Central Asia, volume V, Development in Contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, eds C. Adle & Irfan Habib, 934 p., 5 maps, numerous ills and figs, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, 2003.

6- History of Civilization of Central Asia, Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century, President C. Adle, co-eds M. K. Palat and A. Tabyshalieva, volume VI, 1033p., 7 maps, numerous ills and figs, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, September 2005.

Prospectus:

1- šnâ’i bâ sinemâ va nakhostin gâmhâ dar filmbardâri va filmsâzi dar Irân, 1277 tâ hodud-e 1284š/1899 tâ hodud-e 1905m., Golestân Palace, Tehran, 1379š/2000. Revised edition as “Ashnâ’i bâ sinemâ va nakhostin gâmhâ dar filmbardâri va filmsâzi dar Irân, 1277 tâ hodud-e 1284 kh./1899 tâ hodud 1905m” (version revue et corrigée de la 1ère édition), 12 ills, Bukhara, vol. 17, no. 17, Téhéran, Farvardin‒Ordibehesht 1380š/21 mars‒30 avril 2001, pp. 322‒375.

Articles:

1- “Contribution à la géographie historique de Dâmghân”, Le monde iranien et l’Islam, Genève‒Paris, 1971, pp. 69‒96.

2- “Les monuments du XIe siècle du Dâmqân”, Studia Iranica, I/2, 1972, pp. 229‒297 (with a contribution by A. S. Melikian-Chirvani on epigraphy), pp. 250‒268.

3- “Un disque de fondation en céramique (Kâšân, 711/1312)”, Journal Asiatique, CCLX/3‒4, 1972, pp. 277‒297.

4- “Negâhi be kongere-ye xâvar-šenâsi-ye Pâris va natâyej-e ân”, Râhnamâ-ye ketâb, XVI/7‒9, Mehr-âzar l352/Fall 1973, pp. 370‒381.

4bis- Abridged translation in Xwândanihâ, 1352/1973.

5- “La bataille de Mehmândust (1142/1729)”, Studia Iranica, II/2, 1973, pp. 235‒241.

6- “Notes sur le Qabr-e Šâhrox de Dâmqân”, Le Monde iranien et l’Islam, Paris‒Genève, II, 1974, pp. 173‒185.

7- “Le Minaret de Masjed-e Jâme’ de Semnân, circa 421‒25/1030‒34”, Studia iranica, V/2, 1975, pp. 177‒186.

8- “Recherche sur le module et le tracé correcteur dans la miniature orientale. I, la mise en évidence à partir d’un exemple”, Le Monde iranien et l’Islam, III, 1975, pp. 81‒105.

9- “Maxime Siroux (Biographie, bibliographie)”, Le Monde iranien et l’Islam, III, 1975, pp. 127‒132.

10- “Notes préliminaires sur la tour disparue de Rey, 466/1073‒74”, The Memorial Volume of the VIth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, Oxford 1972, Tehran, 1976, pp. 1‒12.

11- “Constructions funéraires à Rey circa Xe‒XIIe siècle”, Akten des VII. Internationalen Kongresses für Iranische Kunst und Archäologie München, 7.‒10. September 1976, Berlin, 1976, pp. 511‒515.

12- “Notes et documents sur Mzé-Câbûk, Atabeg de Géorgie Méridionale (1500‒1515) et les Safavides”, Studia Iranica, VII/2, 1978, pp. 213‒249 (with J. L. Bacqué-Grammont).

13- “Notes sur les Safavides et la Géorgie, 1521‒1524”, Studia Iranica, IX/2, 1980, pp. 211‒231 (with J-L. Bacqué-Grammont).

14- “La Compréhension de leur passé par les Musulmans d’aujourd’hui (Notes sur le Monde iranien)”, Actes du quatrième Colloque de l’Association pour l’avancement des Etudes Islamiques, Paris 1981, pp. 171‒208 (edited version of a paper delivered at the Collège de France, 1979).

15- “Une lettre de Kvarkvaré III?”, Bedi Kartlisa, XL, 1982, pp. 228‒236 (with J. L. Bacqué-Grammont).

16- “Un diptyque de fondation en céramique lustrée, Kâšân 711/1312” (Recherche sur le module et le tracé correcteur/régulateur dans la miniature orientale, II), Art et Société dans le Monde iranien, Paris, 1982, pp. 199‒218.

17- “Une lettre de Hasan Beg de ‘Imâdiyye sur les affaires d’Iran en 1516”, Acta Orientala Hung, XXXVI, 1982, pp. 29‒37 (with J. L. Bacqué-Grammont).

18- “Katibe-ye kâši-ye menâr-e Masjed-e Jâme’-e Dâmqân (hodud-e 450/1050). Kohantarin nemune-ye bâzmânde darjây az kârbord-e kâši dar me’mâri-ye Irân/Inscription sur kâši du Minaret de la Mosquée Jâmeʻ de Dâmqân, c. 450/1058. Le plus ancien spécimen en place illustrant l’utilisation du kâši dans l’architecture islamique de l’Iran”, Asar, VII‒IX, 1361š/1983, pp. 297‒300.

19- “Notes et documents sur la photographie iranienne et son histoire. I. Les premiers daguerréotypistes, c. 1844‒1854/1260‒1270”, Studia Iranica, XII/2, 1983, pp. 249‒280 (with Y. Zokâ).

20- “Recherche archéologique en Iran sur le Kumeš médiéval, Rapport préliminaire pour 1982‒1983”, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, avril‒juin 1984, Paris, 1984, pp. 271‒299 et p. 445 (with Louis Bazin, pp. 297‒298).

21- “Quatre lettres de Šeref Beg de Bitlîs (1516‒1520)”, with J. L. Baqué-Grammont, Der Islam, 63/1, 1986, pp. 90‒118.

22- “Katibe’i now-yâfte dar Bastâm-e Kumeš (699/1299‒1300) va Borj-e ârâmgâhi-ye az-miyân-rafte-ye Hesâm al-Dowle yâ Salm-o-Tur dar Sâri/La Frise épigraphique nouvellement découverte à Bastâm de Kumeš (699/1299‒1300) et la tour funéraire disparue de Hesâm al-Dowle ou Salm-o-Tur à Sâri”, Asar, X‒XI, 1986, pp. 175‒183.

23- “Le prétendu effondrement de la coupole du mausolée de Qâzân Xân à Tabriz en 705/1305 et son exploitation politique”, Studia Iranica, XV/2, 1986, pp. 266‒271.

24- “Se ‘Abbâs Mirzâ-ye Nâyeb al-Saltane/Les trois ‘Abbâs Mirzâ Nâyeb al-Saltane”, Âyandeh, XIII/1-3, Farvardin‒Xordâd 1366/printemps 1987, couverture et pp. 35‒41, 192‒194.

25- “Yâddâšti bar Masjed-madrese-ye Zuzan”, Asar, vols 15‒16, 1367š/1989, pp. 231‒248, 11 ills.

26- “Autopsia, in Absentia. Sur la date de l’introduction et de la constitution de l’Album de Bahrâm Mirzâ par Dust-Mohammad en 951/1544”, Studia Iranica, 19/2, 1990, pp. 219‒256, pls. X‒XIII.

27- “Entre Timurides, Mogols et Safavides, Notes sur un Châhnâmé de l’Atelier-Bibliothèque Royal d’Ologh Beg II à Caboul (873‒907) 1469‒1502”, Catalogue de vente Drout-Richelieu, Vendredi 15 juin 1990, Etude Daussy-Ricqlès, Paris, 1990, pp. 136‒147.

28- “Notes sur les première et seconde campagnes archéologiques à Rey. Automne-hiver 1354‒55/1976‒77”, Contribution à l’histoire de l’Iran, Mélanges offerts à Jean Perrot, éd. F. Vallat, Paris, 1990, pp. 295‒302, 5 pls.

29- “A Sphero-conical Vessel as Fuqqâ’a, or a gourd for ‘beer’”, en collaboration avec A. Ghouchani, Muqarnas, IX, 1992, pp. 72‒92.

30- “Investigations archéologiques dans le Gorgân, au pays turcoman et aux confins irano-afghans”, Mélanges offerts à Louis Bazin, éd. J-L. Bacqué-Grammont et R. Dor, Paris, 1992, pp. 177‒205.

31- “Jardin habité ou Téhéran de Jadis, Des origines aux Safavides”, Bicentenaire de Téhéran, éds C. Adle et B. Hourcade, pp. 15‒37, Paris, 1993.

31bis- Traduction persane : “Bâq-e maskuni yâ Tehrân dar gozaštehhâ-ye dur, az peydâyeš tâ ‘ahd-e safavi”, Tehrân paytaxt-e devist sâleh, eds C. Adle et B. Hourcade, Tehrân, 1375š/1997, pp. 1‒34.

32- “Les artistes nommés Dust-Mohammad au XVIe siècle”, Studia Iranica, 22/2, 1993, pp. 219‒296, 10 pls.

33- “Archéologie et arts du Monde iranien, de l’Inde Musulmane et du Caucase d’après quelques recherches récentes de terrain, 1984‒95”, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, janvier-mars 1996, Paris, 1996 (paru 97), pp. 315‒376.

34- “De la peinture à la photographie, naissance de la daguerréotypie iranienne”, Images, no. 36, Paris, 1997, pp. 6‒11.

35- “Une contrée redécouverte: le Pays de Zuzan à la veille de l’invasion mongole”, L’Iran face à la domination mongole, éd. D. Aigle, IFRI., Paris et Téhéran, 1997, pp. 24‒36.

35bis- “Xetteh’i bâz-yâfteh, Molk-e Malek-e Zuzan dar âstâneh-ye hamle-ye Moqol”, Majmu’eh-ye maqâlât-e Kongreh-ye târix-e me’mâri va šahr-sâzi Irân, Arg-e Bam, Kermân, 5 vols, Téhéran, 1374‒76š/1995‒97, vol. III, pp. 53‒70.

35ter- “Xetteh’i bâz-yâfteh, Molk-e ‘ Zuzan’ dar âstâneh-ye hamle-ye Moqol”, tr. Asghar Karimi, Bukhara, Téhéran, vol. 11, no. 67, Mehr-Aban 1387/novembre 2008, pp. 102‒120.

36- “Negâhi be bardâshthâ va didgâhâ-ye shomârgâni (digitâli) va fotogrâmetri shode-ye Zuzan va Bastâm”, Asar, vols 29‒30, pp. 90‒108, 13 ills + 2 in coul. sur couvertures, 1377š 998.

37- “New Data on the Dawn of Mughal Painting and Calligraphy”, Making of Indo-Persian Culture, Indian and French Studies, eds. M. Alam, F. Nalini Delvoye & M. Gaborieau, pp. 167‒222, 16 ills, New Delhi, 2000.

38- “Khorheh, The Dawn of Iranian Scientific Archaeological Excavation”, Tavoos, no. 3 and 4, Spring and Summer 2000, pp. 4‒29, accompagné d’une version persane intitulée “Khorheh, talieʻ-ye kâvosh-e ‘elmi-ye Irâniyân”, pp. 226‒249.

39- “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran. 1899 to ca 1907 AD/1277 to ca 1284 kh” (Second version)/Ashnâ’i bâ sinemâ va nakhostin gâmhâ dar filmbardâri va filmsâzi dar Irân, 1277 tâ hodud-e 1284 kh./1899 tâ hodud 1905m. (Tahrir-e dovvom)”, 52 ills, Tavoos, nos 5‒6, texte persan pp. 58‒90, texte anglais pp. 180‒215, Téhéran, 1379š/2000-01 (paru été 1380sh/2002).

40- “Sâheb Nasaq, ʿAli Khân va Sardâr Homâyun-e Vâli”, Bukhara, bahman-esfand 1381/February‒March 2003, vol. V, no. 28, pp. 36‒55, 5 ills.

41- “Khorheh dar nakhostin tasavirash, taliʻe-ye kâvoshhâ-ye ‘elmi dar Irân (nime-ye dovvom-e qarn-e 19 milâdi)” (Khoreh présenté dans ses premières images, 2e moitié du 19e s.), dans Kâvoshhâ-ye bâstânshenâsi-ye Khorhe (Archaeological Excavations at Khorhe) par M. Rahbar, Téhéran, 2003, pp. 165‒180.

42- “Qanats of Bam: An Archaeological Perspective. Irrigation system in Bam, its birth and evolution from the prehistoric period up to modern times”, Qanats of Bam, A Multidisplinary Approach, eds M. Honari, A. Salamat et al., pub. UNESCO Tehran Cluster Office, Tehran, 2006, pp. 33‒85, 20 figs. in colour.

43- C. Adle, K. Ono, E. Andaroodi et al., “3DCG Reconstruction and Virtual Reality of UNESCO World Heritage in Danger: The Citadel of Bam”, Progress in Informatics, pub. National Institute of Informatics (NII), no. 5, March 2008, Tokyo, pp. 99‒136, 61 figs. in colour.

44- “ La Mosquée Hâji-Piyadah/Noh-Gonbadân à Balkh (Afghanistan), un chef d’œuvre de Fazl le Barmacide construit en 178‒179/794‒795 ?” , Comptes redu de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (CRAI), vol. I (séances: janvier‒mars 2011), Paris, 2011, pp. 565‒625.

Directed and Supervised Publications:

1- History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol. III, The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750, edited by B. A. Litvinsky, pub. UNESCO, Paris, 1996.

2- History of Civilizations of Central Asia, vol. IV, The Age of Achievement, A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century, 2 vols, eds M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth, pub. UNESCO, Paris, 1998‒2000.

3- History of Civilization of Central Asia, volume V, Development in Contrast: From the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, ed. with Irfan Habib, 934 p., 5 maps, numerous ills and figs, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, 2003.

4- History of Civilization of Central Asia, Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century, President C. Adle, co-eds M. K. Palat and A. Tabyshalieva, volume VI, 1033 p., 7 maps, numerous ills and figs, UNESCO Publishing, Paris, septembre 2005.

Encyclopaedia Entries and Reference Essays:

1- “Kashi”, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. IV, 2nd ed., Leiden, 1978, pp. 701‒702.

2- “Bestâm”, Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, IV/2, pp. 1771‒80, New York, 1989. NB: les éditeurs ayant procédé à une réduction exagérée des pls de cette notice (figs 17 et 18), elles ont du être reproduites à la fin du vol. IV, dans les “addenda et corrigenda”.

3- “La reconstruction photogrammétrique de la Mosquée-Médressé de Zuzan”, Bulletin, Fondation Max Van Berchem, Genève, no. 4, novembre 1990, pp. 1‒2.

4- “Daguerreotype”, Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. VI, pp. 577‒78, Columbia University, New York, 1993.

5- “Dâmgân”, Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. VI, pp. 632‒38, Columbia University, New York, 1993.

6- “Dust-Mohammad” [The Calligrapher], Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, New York, 1996, vol. VII, p. 601.

7- “Herat, Afghanistan”, résumé d’une communication intitulée “Keeping a City’s Memory Alive: Rescuing Herat’s Endangered Monuments”, The Future of Asia’s Past, Preservation of the Architectural Heritage of Asia, p. 28, Los Angeles, 1996.

8- “Damghan” et “Bastam”, entries in The Dictionary of Art, London.

9- “Dust-Mohammad” [the Painter], Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, New York, 1996, vol. VII, pp. 602‒603.

10- “Investigations et relevés archéologiques à Zuzan dans le Khorassan, à la frontière irano-afghane, 1988‒1999”, Bulletin de la Fondation Max van Berchem, Genève, no. 13, Décembre 1999, pp. 2‒6,

11- “Faryumad”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Colombia University, vol. F, pp. 384‒385, New York, 2000.

12- “Zawzan”, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., vol. XI, Leiden, 2002, pp. 471‒472, 1 fig. and pl. X.

13- “Dâstân-e sabt-e Takht-e Jamshid, Naqsh-e Jahân va Choghâ-Zanbil dar UNESCO”, Bukhara, vol. 11, no. 62, Khordâd‒Shahrivar 1386/May‒September 2007, pp. 266‒68.

14- “Changement climatique, Qanât /Kâriz: système d’irrigation pour un développement durable”, p. 58 in E. Fouache, “Le passé des villes pour comprendre leur futur”, in Géoscience, no. 10, décembre 2009, pp. 54‒61.

On Maps and Cartography:

1- Carte no. 1, “Le littoral du Gujarat au début du XVIe s.”, Mare luso-indicum, I, 1971.

2- Carte no. 2, “Centres politiques et commerciaux cinghalais au début du XVIe s.”, Mare luso-indicum, I, 1971.

3- Carte no. 3, “La navigation d’Albuquerque de Socotra à Ormuz”, Mare luso-indicum, I, 1971.

4- Carte no. 2, “Le Golfe Persique au début du XVIe siècle”, Mare luso indicum, II, 1973.

5- Carte no. 3, “Garun et la côte de Perse”, Mare luso indicum, II, 1973.

6- Cartes politiques du Monde iranien (collaboration à la réalisation de), Atlas historique, G. Dubuy, Larousse 1978.

7- “Iranian World”, carte sur double page in 4°, publiée par A. S. Melikian-Chirvani dans Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, Londres, 1982.

Articles for General Readership:

1- “Iran islamique” (histoire de l’), Le Grand Larousse Encyclopédique, pp. 6433‒6437.

2- “Safavides (l’Iran des)”, ibid.

3- “Calligraphie”, L’Iran d’aujourd’hui, Paris, 1975, p. 30.

4- “Le Mausolée d’Abu-Yazid Bastâmi”, Dossiers Histoire et Archéologie, Archéologia, no. 122, 1987, pp. 72‒73.

5- “A la recherche des vestiges aux confins irano-afghans”, Archéologies, 20 ans de recherches françaises dans le monde, foreword by President Sarkozy, preface by Minister of Foreign Affairs, Maisonneuve et Larose—ADPF/CIC, Paris, 2005, pp. 571‒573.

Book Reviews:

1- R. Savory, Iran under the Safavids, Cambridge, 1980, in Revue française d’Histoire d’Outre-Mer, LXIX, 1982, pp. 278‒281.

2- O. Grabar et S. Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History, in Studia Iranica, XII/1, 1983, pp. 129‒131.

3- M. S. Simpson, The Illustration of an Epic, New York et Londres 1979, in Studia Iranica, XII/1, 1983, pp. 131‒133.

4- Lowery, G. and M. C. Beach et collabrateurs, A Jeweler’s Eye, Islamic Arts of the Book from the Vever Collection et An Annotated and Illustrated Checklist of the Vever Collection, Washington, 1988, Studia Iranica, XX/1, 1991, pp. 164‒168.

Abstracts in Abstracta Iranica (vol., année, p./no.):

A- Abstracta, critical, analytical:

-

2, 1979: 24‒25/70; 171‒173/565.

-

3, 1980: 6‒8/26‒27; 84‒85/325.

-

5, 1982: 35‒36/151; 89‒90/336; 124‒132/451‒453; 135‒136; 465.

-

7, 1984: 80/307; 95/357; 95‒96/359; 133/471; 224/814.

-

8, 1985: 56‒57/253; 69/297; 72/306; 81/339; 103/406; 107/426; 169/650.

-

9, 1986: 130/489; 135/503; 138/512; 144‒145/540; 148‒149/548; 151‒152/555.

-

10, 1987: 7‒8/19; 20‒21/53; 90‒91/289; 97‒98/320; 109‒110/373; 121/416; 133‒134/458; 146‒147/513; 151‒152/526; 152‒153/ 531; 153/533;154/536; 155/540; 155/541; 157/547; 158/553; 159‒160/556; 160/559; 161/561; 161/562; 163‒164/571; 261/933.

-

11, 1988: 12‒13/42; 46/170; 95/363; 183‒184/702.

-

12, 1989: 34/143; 46/174; 55/198; 83/337; 84/339; 86/349; 144/569; 152/596; 152‒153/597; 153/598; 153/599; 154/600; 154/601; 154/602; 157/608; 160/614; 261/1014.

B- Abstracta, descriptive:

-

3, 1980: 118‒119/414.

-

4, 1981: 90‒91/339; 93/348; 95/354.

-

5, 1982: 8‒9/30; 9/31; 11/39; 37/153; 76/291; 92/345; 132‒133/457; 134‒135/ 462; 197/655; 202/682; 216/727.

-

6, 1983: 9‒10/32; 33/133; 33‒34/134; 65/257; 66.

-

7, 1984: 8/24; 11/35; 89/338; 89/338; 122/433; 123/436‒437; 123‒124/438; 126/144; 127/446; 129/451, 452; 129‒130/455; 130/457; 130‒131/459, 460, 461, 462; 132/464; 178/619; 232/836.

-

8, 1985: 12‒13/50; 13/51; 60/264; 66/283; 85/347; 99/390; 101‒102/400; 107/424.

-

9, 1986: 137/507; 149/550; 150‒151/554; 153/558.

-

10, 1987: 26‒27/66; 83‒84/253; 109/371; 117/399; 119‒120/409;124/428; 124‒125/429; 155/537; 155/538; 155/539; 156/544; 156/545; 157/548; 157‒158/549.

-

11, 1988: 11/38; 24/77; 109/425; 118/467; 181/693.

-

12, 1989: 87/352; 161/618; 142‒143/568; 149‒150/591.

Reports:

1- Rapport sur les peintures persanes et orientales conservées au Musées d’Etat géorgien d’art Shalva Amiranashvili à Tbilissi, UNESCO, Paris, Août 1995, 63 p., 10 pls.

2- Protection des monuments de l’Afghanistan, Dossier pour l’Inscription des Buddhas et site de Bamiyan sur la liste du Patrimoine culturel Mondial, Unesco, 1997‒98.

3- Archaeological Comprehensive Management Plan for Bam and its Cultural Landscape, Sixth Stakeholders’ Meeting for the Final Draft Comprehensive Management Plan of the World Heritage Property of Bam and its Cultural Landscape, Bam, 14‒17 April 2007.

4- Rapport pour la Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghansitan (DAFA) : A preliminary draft report on the Noh-Gonbad/Gonbadân (Hâji-Piyâda) ‘Mosque’ at Balkh, A masterpiece and one of the earliest religious Islamic buildings in the East, Early 8th to the 1st half of the 9th centuries, Paris 2007.

Ready for Publication:

Books:

1- Proceedings of the International Training Course on Qanats, C. Adle ed., pub. Markaz-e Beynolmellali-ye qanât va sâze-hâ-ye târikhi-ye âbi, bâ moshârekat-e UNESCO/The International Center on Qanats and Historic Hydraulic Structures (ICQHS), under the auspices of UNESCO, Yazd.

2- Communications of the Conference concerning: “Qajar Epoch, Art and Architecture”, Londres, British Institut of Persian Studies, SOAS, 1st‒4th September 1999, eds C. Adle & P. Luft, Londres.

Papers:

1- “Birth of Early Irrigation Systems in Connection with Qanâts in Iran”, in International Training Course on Qanats, A Multidisciplinary Approach to Integrating Traditional Knowledge with Modern Development, Yazd, 1 to 4 July 2007, ed. C. Adle, UNESCO, IQHS (International Centre on Qanats and Historic Hydraulic Structures, Yazd).

2- “Balkh as a World Cultural Landscape”, Current Status of Cultural Heritage in Afghanistan, UNESCO Office, Kabul.

3- “ Bastâm, Noh-Gonbadân/Hâji-Piyâdah de Balkh et Zuzan, trois mosquées du début de l’ère islamique au Grand Khorassan d’après les investigations archéologiques”, Le grand Khorassan, Louvre Museum, Paris.

4- “Photography in Persia. The First Two Decades: 1839‒1860”, in Qajar Epoch, Art and Architecture, eds C. Adle & P. Luft, London.

5- Rapport sur la première Campagne de Fouilles archéologiques à Rey, 5 fasc., textes et pls, remis au Gouvernement iranien depuis 1977.