Introduction

There is an ever-growing literature on anti-EU mobilization (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2016; Magalhães, Reference Magalhães, Nielsen and Franklin2017; Zeitlin et al., Reference Zeitlin, Nicoli and Laffan2019 to name a few). Among others, Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) discuss the likely mark of political representation in the near future and point to the centrality of the EU conflict in mobilizing not only challenger and anti-EU parties but, increasingly, also mainstream parties. Eurosceptic parties have certainly been the main drivers of EU politicization (Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2012). However, in recent years, the pattern of competition between government and opposition (including the mainstream opposition) has also been interested by competition over the EU (Dolezal and Hellström, Reference Dolezal, Hellström, Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Charalambous et al., Reference Charalambous, Conti and Pedrazzani2018). Ultimately, a broad consensus has emerged in the literature about the increased politicization of European integration in member states (Hurrelmann et al., Reference Hurrelmann, Gora and Wagner2015; Hoeglinger, Reference Hoeglinger2016). This process consists of divides resulting in increased issue salience (visibility), actor expansion (range) and actor polarization (positional direction) regarding conflict over the EU (Hutter and Grande, Reference Hutter and Grande2014; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019).

Although this process has been portrayed as involving citizens and parties, what is yet not fully clear is whether a nexus exists between these two levels. Several studies show the diverse, often conflicting nature of EU attitudes between parties and their voters (Vasilopoulou and Gattermann, Reference Vasilopoulou and Gattermann2013; Sorace, Reference Sorace2018). There is a more limited number of studies which analyze how EU attitudes affect voting behavior, but they are generally focused on EP elections (Spoon and Williams, Reference Spoon and Williams2017; Treib, Reference Treib2020), individual countries (among others see Gabel, Reference Gabel2000; Tillman, Reference Tillman2004; Markowski and Tucker, Reference Markowski and Tucker2010; Hobolt and Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Conti et al., Reference Conti, Di Mauro and Memoli2022), single parties or single party families (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2015; Carrieri and Vittori, Reference Carrieri and Vittori2021). Few comparative works are exception to this, but they are built on observations dating back to twenty or more years ago (De Vries, Reference De Vries2007, Reference De Vries2010) or on different data from those used in this study (Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021). Moreover, the above studies are challenged by other works that maintain EU attitudes have only limited observable effects on national elections (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2012; Miklin, Reference Miklin2014).

In this article, we are keen to move a step further and investigate, through the comparative analysis of five EU countries (Austria, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands) what happens when we look at more recent first order national elections and at both electoral demand and political supply. To this aim, we study the degree to which party attitudes toward the EU and the voting preferences of citizens are connected. More specifically, our analysis systematically sets out to investigate the following questions: Does a link exist between parties and their voters regarding European integration? Do EU issues play a significant role in the voting preferences of citizens in national elections?

This paper proposes three ‘EU positional distance’, ‘EU party salience’ and ‘EU party ideology’ hypotheses. The first one posits that the electoral support of parties is related to the positions parties take on the EU. The second one argues that the effect of the EU positional distance between parties and voters is mediated by the salience that parties assign to the EU. The third one predicts that EU positions are important for the likelihood to vote for both Europhile and Eurosceptic parties. In line with our hypotheses, our empirical findings show that a voter's propensity to vote (PTV) for a given party increases when they are positioned closer to each other on the EU issue. Furthermore, we show that the salience parties assign to the EU moderates the impact of EU positional distance on the voting intentions in national elections. In the analysis, we also compare the relative impact of EU issue voting to other issue divides. Finally, our findings demonstrate that the EU distance is a more significant voting predictor among Europhile parties than among Eurosceptic ones.

This study makes use of mass survey data, expert survey data, and social media (Twitter) data to test our three hypotheses. Such a combination of data has never been used before to test a set of hypotheses on a wide array of factors that are expected to explain voter mobilization on the EU. The combined use of voter and party positions to measure the party-voter positional distance on the EU (our main independent variable) also represents an original contribution of our study. Finally, the novelty of our research is also grounded in the use of a relatively underexploited source of data (Issue Competition Comparative Project, ICCP) that allowed us to focus on national rather than on EP elections (as it would be more common for this kind of work), and to gather information on public opinion as well as on party communication on Twitter.Footnote 1

The article is organized as follows. In the next two sections, we review the literature and discuss our hypotheses. In a specific section, we then illustrate our data and method. The subsequent part of the paper is entirely devoted to empirical analysis. Some conclusive remarks will summarize the main findings of our work and discuss their theoretical relevance.

EU issue voting

‘EU issue voting’ is defined as ‘the process whereby individual preferences over European integration directly influence the voting choices in national elections’ (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010: 92). By referring to EU issue voting, the assumption is that voting behavior is mainly grounded in issue competition rather than social identities. De Vries' seminal work showed that the congruence between citizens' attitudes toward the EU and parties' positions on the EU can affect national elections if parties make the differences between them sufficiently salient. The distance between the EU positions of parties and those of individuals matters more in countries in which the conflict over the EU is stronger (De Vries, Reference De Vries2007), and EU issue voting is more robust where there are parties that exert an issue ownership over the EU (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010).

The question whether EU-concerns influence voters' choices has often been addressed in the empirical literature, at least since the late 1970s (De Vries and Tillman, Reference De Vries and Tillman2011). Much of that literature looked at voting in EP elections, while this research focuses on national parliamentary elections, a focus which is not completely new (Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021) but is certainly less frequent. The EU issue has long remained a ‘sleeping giant’ in many European countries due to the lack of EU mobilization by the mainstream political parties (Van der Eijk and Franklin, Reference Van der Eijk and Franklin2009). In the last decades, citizens have witnessed the deepening of EU prerogatives, with the authority transfer toward the EU institutions triggering controversies over this process at the domestic level (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Moreover, political parties have become more prone to draw attention on EU issues, making this conflict more politicized in national party systems (Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). As parties are responsive to shifts in public opinion (Williams and Spoon, Reference Williams and Spoon2015; Gross and Schäfer, Reference Gross, Schäfer, Bukow and Uwe2020), the growing influence of the EU among citizens' concerns has been reflected in making the EU more salient (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). Even mainstream parties, which have traditionally been more reluctant to make the EU prominent in their supply, have been pushed to respond to a new scenario, in which the EU is a crucial dimension of party competition (Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2020; Hobolt and Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Braun and Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021). Finally, a multiple set of crises – Brexit, the Euro crisis, and migration crises – have constituted windows of attention for the EU integration process, making the EU issues more influential on the voting behavior at the domestic level (Hobolt and Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Magalhães, Reference Magalhães, Nielsen and Franklin2017).

Therefore, a set of processes – the deepening of EU integration, the changing public attitudes and the consequences of multiple crises – have made political leaders more likely to collide on European integration. The salience assigned by parties to the EU has likely triggered the overall effects amongst voters, reinforcing EU issue voting at the domestic level (De Vries, Reference De Vries2007; Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021). Moreover, party ideological polarization on Europe has offered voters with choice on a diversified set of positions, contributing to enhancing the impact of the EU issues on the voting process (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010; Hobolt and Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020).

The party-voter linkage on the EU

In the present study we focus on the party-voter dyad. According to Hellström (Reference Hellström2008), parties are capable of strongly affecting public perceptions and attitudes regarding EU issues by effectively cueing constituents (see also: Pannico, Reference Pannico2020). At the same time, the complexity of EU issues has made voters increasingly reliant on party assessments and on their framing on this issue dimension. Charalambous et al. (Reference Charalambous, Conti and Pedrazzani2018) showed that in the presence of a political elite of public office holders who tend to reiterate the traditional elite consensus on Europe, party leadership has become more sensitive to popular pressure and to Euroscepticism. We aim to test, empirically, if the electoral mobilization of citizens on the EU represents nowadays a relevant dimension of political competition. We argue that, in order to confirm the relevance of EU issue voting, we should find evidence of a pattern of political behavior linking citizens and parties resulting in electoral mobilization.

Parties have been theorized as competing for votes by taking different positions on the same issues and by assigning salience to different matters through a process of selective issue emphasis (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Bélanger and Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). The combination of the positions taken and the issues primed by parties create their public image. According to Sartori (Reference Sartori1969: 209): ‘conflicts and cleavages may be channeled, deflected and repressed or, vice versa, activated and reinforced, precisely by the operations and operators of the political system’. Party positional polarization and issue salience (together with media coverage) are the core devices for issue politicization as they potentially reinforce the electoral relevance of issues, such as the EU ones (Van Spanje and de Vreese, Reference van Spanje and De Vreese2014).

The concept of salience in party competition hinges on the notion of issue ownership or credibility; that is, the degree to which a party has developed a good image in handling a certain policy issue (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Van der Brug, Reference Van der Brug2004). Parties choose to dismiss certain conflicts, which could potentially jeopardize their electoral stability or, vice versa, they assign salience to conflicts that could constitute an electoral asset. Political actors tend to mobilize voters by prioritizing the issue they own, and shelving those issues that could provide electoral advantages for their opponents (Bélanger, Reference Bélanger2003; Bélanger and Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). By emphasizing EU issues, parties have the ability to alter the systemic salience of European integration in the domestic agenda and transform it into one of their signatory issues for political contestation (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Hutter and Grande, Reference Hutter and Grande2014). Thus, the salience that political parties ascribe to these issues may translate into new voting alignments along the pro-/anti-European dimension (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010; Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2012).

In addition to that, scholarship has defined policy shifts on the pro/anti-EU dimension as an important part of the EU conflict (Hutter and Grande, Reference Hutter and Grande2014; Grande and Hutter, Reference Grande and Hutter2016; Hoeglinger, Reference Hoeglinger2016; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). By expressing an extreme position on a certain issue, a political party may actually boost that issue's visibility, while, when a party adopts moderate stances on a policy, it often aims to overshadow that issue (De Vries, Reference De Vries2010). Issue salience may interact with party positional strategy. Consequently, policy position and salience manipulations are closely intertwined and together they build the overall EU issue entrepreneurship of parties (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Hobolt and De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015). It is, however, contested in the literature whether, in their competition, parties prioritize selective issue emphasis, or shift their position on a shared policy dimension.

According to the literature, the politicization of the EU conflict was mainly driven by (radical right and radical left) Eurosceptic parties to increase their shares of votes (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012). These parties assigned salience to the EU issues on which, by underlining the economic and cultural anxieties within society related to European integration, they perceived to hold electoral opportunities (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). On the contrary, Europhile (mainstream) parties tended to dismiss the EU issues from the debate, as they sought to maintain their electoral primacy on the left-right dimension (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2012). In the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis, the Eurosceptic parties have further strengthened their politicization efforts on this conflict, exploiting the growing popular dissatisfaction over European integration (Charalambous et al., Reference Charalambous, Conti and Pedrazzani2018; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). However, this Eurosceptic supply has led Europhile parties to react, adopting a more confrontational strategy on the EU issues (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). Indeed, many mainstream parties have responded to the challenge of Eurosceptic parties by increasingly emphasizing the EU issues, especially during the 2019 EP elections (Braun and Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021; Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021).

By ascribing more salience to EU issues, Europhile parties may have sparked off electoral responses, winning over votes on the EU dimension. According to Carrieri (Reference Carrieri2020), at the 2019 EP elections, Europhile parties became more likely than Eurosceptic parties to gain electoral preferences on the EU dimension. This Europhile voting pattern may also be due to the outcomes of the Brexit referendum, with the majority of citizens outside the UK reappraising the utilitarian benefits related to European integration and, thus, rejecting the leave option for their own country (De Vries, Reference De Vries2017). Other works have identified the voting potential on the EU dimension of Europhile parties (Hobolt and Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Turnbull-Dugarte, Reference Turnbull-Dugarte2020). In short, by acting as politicization agents on European integration, Europhile parties may have fostered the rise of a conflict on the EU in the party system. However, Eurosceptic parties have not deflected their strategic emphasis on EU issues to reap electoral gains (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Treib, Reference Treib2021). Ultimately, in the article, we seek to analyze the influence of EU issue voting in the national elections, predicting that this electoral phenomenon matters for both Europhile and Eurosceptic parties.

In our work, we rely on measures of both position and salience to estimate the EU attitudes of parties. We hypothesize that, conditional on voters' preferences, the more salience a party gives to the EU issue, the more support the same party will get (from those voters who are closest to its position). Thus, we turn to the combination of issue position and issue salience to trace the EU attitudes of parties (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012). Through a careful examination of the relationship between EU salience and position at party level on the one hand, and the voting preferences of citizens on the other hand, our analysis sheds light on how EU conflict contributes to determining the voting preferences of citizens and to aggregating results in national elections. This is done through the empirical test of the following hypotheses:

H1: The smaller the distance between the party and the voter position on the EU, the higher is the voter's likelihood to vote for the party (EU positional distance hypothesis).

H2: The higher the salience of the EU topic for the party, the stronger the impact of EU distance on the likelihood to vote for it (EU party salience hypothesis).

H3: The EU distance influences the likelihood to vote for both Europhile and Eurosceptic parties (EU party ideology hypothesis).

In the following sections, we test whether an electoral connection really exists between EU attitudes and voting or, alternatively, the argument about EU attitudes having only limited observable effects on national elections is more acceptable.

Data and method

We test our hypotheses, relying on a mix of data from various sources. To start with, we make use of the ICCP survey data which covers citizens' attitudes to a large array of issues and voting preferences (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Emanuele, Maggini, Paparo, Angelucci and D'Alimonte2019). These CAWI surveys were designed by a pool of country experts and conducted during the month preceding the general elections in the five countries under analysis (2017–18).Footnote 2 The focus on five countries is of course a limitation of our study, as we do not dispose of the full EU membership. At the same time, the novelty of our approach rests in the unique combination of different data sources that would not be possible through use of other large-scale datasets. Furthermore, although we dispose of a limited number of countries, they represent relevant variations within the EU, as the sample includes Northern and Southern European countries, as well as the three largest and two medium-size EU member states that, all together, stand for a clearly identifiable region such as Western Europe.

From this dataset, we consider as a dependent variable the PTV of public opinion, measured as an eleven-point continuous variable from 0 (no probability) to 10 (highest probability of voting for a given party). The PTV is also known in the literature as ‘voting probability’, ‘party preference’ or ‘party support’. This variable provides us with the voter preferences for all the available parties in the ICCP surveys. Conceptually, this measure stems from Downs' work (1957), who distinguished two different stages in the voting decision process. During the first stage, individuals assess their probability of supporting each party competing in the elections, depending on the utility expected by voting for that party. During the second stage, individuals choose the party they support the most, fulfilling their utility function. The PTV captures the first stage of voting, encompassing individuals' orientations toward all available parties (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007). This measurement of the dependent variable also overcomes the main problems rooted in alternative measurements based on the categorical choice of the respondent for one given party. In pure operational terms, by multiplying the number of respondents by the number of parties under study (so as to create party-voter dyads), the PTV tackles the problem of the low number of observations that may result from dichotomous voting choice measurements that may affect, in particular, the analysis of systems with several small parties (De Vries and Tillman, Reference De Vries and Tillman2011; Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007). The use of PTV allowed us to develop linear regression models (OLS) for the test of our hypotheses, where we also include country dummy variables to allow a cross-national generalizability of our findings. To take into account the fact that there are multiple observations within the same individual we ran models clustering the standard errors on individuals.Footnote 3

Moving to the party level, we make use of the 2017 Chapel Hill Expert Survey dataFootnote 4 (CHES; Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly and Koedam2017) to grasp party EU salience and EU position. CHES is based on an expert assessment of party positions and issue emphases on several dimensions with the respondents usually relying on a large set of information (i.e. roll-call votes, policymakers' statements, television debates, media discourse etc.: on this point see Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, De Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenburgen and Vachudova2015) to make their estimates. The CHES EU Salience is measured by asking experts to assess the relative salience of European integration in the party's public stance in a range from 0 (European integration not important at all) to 10 (European integration as the most important issue). We rely on CHES data also to measure the party's EU position, as the experts located parties along a seven-point scale varying from 1 (strongly opposed to European integration) to 7 (strongly in favor of European integration).

Beyond information about broad political discourse (better captured by CHES), the recent literature has underlined the importance of social media communication, particularly on Twitter, in catching parties' strategic and programmatic efforts (D'Alimonte et al., Reference D'Alimonte, De Sio and Franklin2020). The ‘press release assumption’ (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, De Angelis and Emanuele2018) postulates a direct influence of parties in mobilizing users on Twitter, along with an indirect impact on a broader audience with the traditional media (newspapers and television) conveying parties' tweets to the mass public. Twitter has been considered by scholarship as very much ‘media oriented’ and an ideal tool for influencing media coverage (McCombs et al., Reference McCombs, Shaw and Weaver2014). In these terms, Twitter increasingly performs an agenda-setting function in politics with news media treating Twitter feeds as news. Confirmation of this phenomenon spreading across Europe has been offered by several scholars (Paulussen and Harder, Reference Paulussen and Harder2014; von Nordheim et al., Reference von Nordheim, Boczek and Koppers2018) who demonstrate how social media have become a ‘convenient and cheap beat for political journalism’ (Broersma and Graham, Reference Broersma and Graham2013).

Conveniently, the ICCP collected information on the Twitter campaign of political parties and leaders during the month preceding the elections. The official Twitter profiles of parties and their frontrunners were monitored, calculating the number of party/leader tweets dedicated to each relevant issueFootnote 5. This unique dataset gives us a chance to gauge the Twitter EU Salience to complement the more widely used CHES EU salience of parties that is more likely to be shaped in the longer term, irrespective of the specific climate of the electoral campaign. ICCP measured the proportion of a party's tweets dedicated to the EU issue, over the total of issue-related tweets during the campaign. In the end, in our analysis, we rely on the two complementary measures of CHES and Twitter EU Salience to capture the fully-fledged party emphasis on the EU across different arenas and media outlets.Footnote 6

For the simultaneous analysis of parties and voters, and to build the independent variables for the test of our hypotheses, we followed an established method in the literature (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007) by creating a stacked (by party) data matrix that multiplies all individual observations for each party (= respondent × number of parties). In doing so, our unit of analysis becomes the voter-party dyad. As to the selection of party cases, we included all the parties available in the ICCP surveys which could be matched with the CHES surveysFootnote 7 (for more specific information on the number, the name and the positions of these parties, see the online appendix: Table A1).

Hence, turning to the independent variables of our study, the first one related to EU position is operationalized as the party-voter EU distance. This variable is inspired by the Downsean ‘smallest distance theory’ or ‘proximity’ (Downs, Reference Downs1957) that postulates that, in order to maximize their electoral utility, voters choose the party that is closest to (i.e. with the smallest distance from) their policy position. Our objective is to verify how much the EU party-voter distance explains the voting preferences in first order national elections, controlling for other factors. To this aim, we measured the absolute distance between CHES party positions and the voter self-assessed position on the EU (ICCP), a yardstick that indicates the voters' congruence (or discrepancy) with party positions along the pro-/-anti-EU dimension (De Vries and Hobolt, 2016).Footnote 8

We calculated the absolute distance between the position of the voter and that of the party following a common practice in the literature on EU issue voting (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, Van der Ejik and Franklin2007; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Spoon and Tilley2009; De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Franklin and Weber2016; De Vries and Hobolt, 2016). Although the spatial voting literature sometimes makes use of squared (‘Euclidean’) instead of absolute distances, several works showed that the linear proximity function tends to outperform the quadratic one and is therefore preferable (Lewis and King, Reference Lewis and King1999; Bølstad and Dinas, Reference Bølstad and Dinas2017). We therefore calculated the absolute distance for the analysis shown in the main text; however, we also performed models with a squared EU distance variable that are shown in the Online Appendix and that prove that our results hold after this test (see: Appendix 7).

ICCP provided us with voter positions, with the respondents locating themselves along a six-point scale, varying from 1 (Leave the EU) to 6 (Stay in the EU). To make the ICCP and CHES scales congruent, we changed the direction of the individual-level scale and standardized the two scales to obtain a new scale, varying from 0 (anti-EU) to 1 (pro-EU). Thus, the EU distance variable, by calculating the positional difference between voters and parties, provides us with all the existing combinations in EU positional distance across the voter-party dyads (with a range between 0 and 1).

To test H1, in the next section models show the impact of the EU distance variable on voting preferences. We included other variables for the control of the independent effects of EU distance on voting preferences. More precisely, since many works contend the bi-dimensional nature of the political space – with party competition being structured by an economic and a cultural dimension (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018) – we plugged into our models another two party/voter distance variables, measuring voters' self-perceived (dis-)agreement with party positions over economic redistributionFootnote 9 and immigration, respectively. As a further test of robustness, the models include left-right positional distance, which is considered one of the most resilient heuristics in the political world (Dalton et al., Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011).Footnote 10 We have checked for potential collinearity among the distance variables, but we only found very weak/weak correlations (as it can be seen in table A3 in the Appendix). This test allowed us to exclude problems of over-control when we include in the model immigration/redistribution positional distances and left-right.Footnote 11

To assess the differentiated patterns of EU issue voting across our cluster of countries, Model 2 includes an interaction between the country dummies and the EU distance variable. This step allows us to test if dynamics of EU issue voting can be generalized to different national contexts, providing an additional validation of our H1.

To test H2, we analyzed if parties that are more committed to emphasizing EU issues are more capable of increasing their electoral support (under the assumption that if EU issues are relevant to them, voters should care about the salience parties assign to the EU). This empirical step ascertains the differentiated impact of EU Twitter and CHES salience. In the relevant models, we plugged both measures of salience to test their moderating effects on voting preferences. Since the two salience measures are moderately correlated (r = 0.46), in order to avoid problems of multicollinearity, we built two separate models (4 and 5) for the Twitter and the CHES salience, respectively. We interacted salience with EU distance to ascertain if the former plays a multiplicative effect on the influence played by the latter. For corroborating the multiplicative power of the EU salience on EU distance, the interaction terms should hold significant and negative effects.

To test the ideological foundation of EU issue voting (H3), we included an interaction term between the party stances on European integration (EU party ideology) and the EU distance. This interaction term allows us to estimate which parties have been more likely to attract voters based on their EU position. Firstly, the party broad EU stance has been operationalized as a dichotomous variable (0 for the Pro and 1 for the Anti-EU type).Footnote 12 If the relationship between EU distance and PTV is stronger for voters of Pro-EU parties the interaction coefficient should be positive, and vice versa for Anti-EU parties. Secondly, we introduced an interaction term between the EU distance variable and the EU party position variable. The latter is a continuous variable accounting for all the existing EU party stances in the CHES dataset. This interaction term allows to identify the degree of EU issue voting by all the different party nuances in the EU integration scale, including a differentiation between soft and hard Eurosceptic/Europhile postures (see: Taggart and Szczerbiak, Reference Taggart and Szczerbiak2002; Hertner and Keith, Reference Hertner and Keith2017). The above tests aim at understanding if the impact of EU integration on electoral preferences has spread across the entire ideological spectrum, affecting both Eurosceptic and Europhile parties.

Furthermore, we analyzed the moderating impact of EU Twitter and CHES salience on the PTVs for the different party types. To assess this, we performed three-way interactions for EU distance by EU party ideology and the two salience measures (considered separately). By plotting these three-way interactions, we seek to ascertain if the salience held a greater multiplicative power on EU issue voting for Europhile or Eurosceptic parties.

Finally, we included several control variables. Although declining, another factor which has traditionally swayed voting preferences is party identification (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960). In the absence of a specific question on party identification in the survey, we used party closeness as a proxy of partisanship (a dichotomous variable). We also introduced party size as control, as respondents may have a tendency to declare their PTV for the largest parties in higher numbers. Finally, we included a set of socio-demographic variables as control: gender, age, years of education, church attendance and town size.Footnote 13

Analysis and discussion

Table 1 shows the models built to test our hypotheses. Model 1 includes the socio-demographic factors, party closeness, party size, the country dummies, and the distance variables. In the model, we found that the EU distance variable is statistically significant, and it is a relevant factor in swaying electoral support for parties. As was easy to imagine, the left-right distance is the most important voting determinant (−2.519) of all positional predictors. But when the effect yielded by the EU distance (−1.398) is compared to the controls of Economic redistribution (0.906) and Immigration (−1.630) positional distance, we find that it stands between the two. The EU distance stands out as a significant voting predictor proving its relation with the electoral preferences and showing a stronger relationship than the Economic positional distance. As to the greater impact of Immigration distance, it is worth noting that the 2017–2018 elections in Western Europe (when the surveys were conducted) occurred during a peak in the conflict on immigration, with virtually all the major parties colliding over this political issue (Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). To sum up, in the analyzed elections, the EU has shaped the electoral preferences of voters, confirming other findings in the literature on the impact of EU issue voting (De Vries, Reference De Vries2007; Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021). This is verified despite other (traditional) determinants, such as left-right, still play a major role in relation to electoral preferences vis-à-vis the EU issue.

Table 1. Linear (OLS) regression models (standard errors in parentheses)

*P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

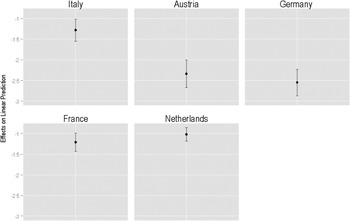

Model 2 includes an interaction term between the individual countries and the EU distance variable, accounting for the generalizability of our results to different national contexts. By plotting the average marginal effects of EU distance by country (Figure 1), we can observe that this variable is significantly related to the likelihood to vote for parties in all the analyzed countries. Although Austria and Germany have epitomized a more marked pattern of EU issue voting, all the countries considered display a negative and significant relationship of EU positional distance with the PTVs. Our analysis has provided evidence about the relationship between the EU issue and voting preferences, a result that can be generalized across different countries. The data support H1 and this allows us to argue that citizens tend to support parties that are closest to their own position on the EU.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of EU distance by country (95% CIs).

Through our analysis, we cannot prove if EU issue voting is associated with the growing authority transfer toward the EU institutions, nor if the catalyst effect of a multiple set of crises – the Euro crisis, the refugee crisis and Brexit – can help explain the phenomenon. Thus, we cannot prove if EU issue voting is linked to the general salience of the EU within society. However, the following step in the analysis allows to shed light on the intervening power of EU salience, and to verify if EU issue voting is dependent on the party strategies of giving (or not giving) emphasis to the EU.

In models 3 and 4, we interacted EU distance with the two measures of salience. The first test seeks to capture the effect of EU distance on PTV conditional on the party's social media campaign (via Twitter). The interaction coefficient is not statistically significant, with the multiplicative effects of Twitter being null and thus not affecting the probability of supporting a party. Crucially, this outcome contradicts the notion of Twitter having a mobilizing effect over European integration. Maybe because it is a media outlet that has not yet reached the mass public but is dominated by a small number of users, from our survey it emerged that Twitter was not able to re-orient voter mobilization based on positional distance. Instead, the intervening power of CHES salience is confirmed. In this case, the interaction term is highly significant and negative, with the voter propensity to support a party, conditional on EU positional distance, being multiplicated by this salience measure. Figure 3 shows that the marginal effect of EU distance varies conditional on the EU salience. Thus, from our analysis, it appears that between the two measures of EU salience, the more comprehensive one based on the CHES expert survey is more impactful than the more specific (and contingent on the electoral campaign) one based on the Twitter communication strategy of party leadership. This is an interesting finding, possibly challenging the notion of the relevance of contestation about Europe on the internet. Certainly, the social media debate about the EU is disproportionately dominated by Eurosceptic voices (Galpin and Trenz, Reference Galpin, Trenz, Caiani and Guerra2017). This is also due to the high political complexity of EU affairs that plays as a deterrent to political communication of these affairs by moderate pro-EU parties on this social platform (Umit, Reference Umit2017). Thus, efforts by parties to make the EU more salient on Twitter may have only a limited influence on voters, but more research on the specific profile of Twitter users would be needed.

Thus, our H2 has received only mixed empirical backing. The interacting power of CHES EU salience appears to indicate that parties need to adopt more eclectic strategies in conveying shortcuts to their constituents in order to spur reactions amongst them on the EU integration dimension. EU issue competition could thus be grounded on a differentiated set of party mobilization activities (that CHES is better able to capture) encompassing electoral manifestos, speeches and statements and roll-call votes, just to name a few, more than on Twitter communication. Future research may identify which communication outlets are more likely to mobilize voters on the EU and consider in greater depth the apparent limitations of Twitter in influencing the phenomenon under analysis Figure 2.

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of EU distance at different levels of EU CHES salience (95% Cis).

To test H3, Model 5 includes an interaction term between the party's broad stance (Pro-EU versus Anti-EU) and the EU distance variable. This interaction allows us to further specify H1. The interaction coefficient is significant and positive (0.469), showing that the relationship is a bit stronger for Pro-EU parties and slightly weaker for Anti-EU parties. As the margins plot shows (Figure 3), in terms of PTV, pro-European parties are more significantly affected by EU positional distance than Eurosceptic parties. Based on a different country sample (with the only overlap of Italy and Germany) and different time points (2017–2018 instead of 2014), our results are more linear than those shown by Torcal and Rodon (Reference Torcal and Rodon2021) who found that only in (a majority) of countries the EU dimension is relevant for the support given to all main parties, whereas in other countries it is relevant only for the support to Eurosceptic parties. The fact that in our analysis the relationship is a bit stronger for Pro-EU parties may show that, over time, the Europhile parties have become more effective in mobilizing voters in this dimension. We will be back on the point later in the text.

Figure 3. Average marginal effects of EU distance by EU party ideology (95% CIs).

Model 6 provides a more fine-grained test of H3 that includes the interaction between EU distance and EU party position (accounting for all the existing party EU stances in the CHES dataset). When plotting this interaction (Figure 4), it can be seen that the degree of EU issue voting is significantly more important for pro-EU parties rather than for Eurosceptic ones. In general, Figure 4 shows a linear effect of the EU distance variable, which increases for the Europhile parties and decreases for the Eurosceptic ones. In particular, the so-called hard Eurosceptic parties (those holding a position that varies from 1.1 to 2.3 in the CHES dataset, such as the National Rally, the League, Alternative for Germany, the Freedom Party of Austria, the Dutch Party for Freedom etc.) display the lowest level of EU issue voting within our sample. The soft Eurosceptic parties (those with a position between 2.6 and 3.4, such as the Five Star Movement and the Dutch Socialist Party) do not perform significantly better than the hard Eurosceptic parties in the EU dimension of electoral mobilization.

Figure 4. Average marginal effects of EU distance by EU party position (95% CIs).

On the contrary, the EU distance matters significantly more for the Europhile parties that display a stronger pattern of EU issue voting. Even more, EU distance appears particularly relevant for those parties displaying higher pro-Europeanism (those parties in a range from 6.1 to 7 on the EU CHES scale, such as the Republic on the March, the Italian Democratic Party, the Austrian and German Greens, the Social Democratic Parties of Germany and Austria, Democrats 66, etc.). Finally, the EU distance constitutes a more significant factor for the moderately Europhile parties (such as, the German Liberals, the Republicans, Forward Italy, Austrian People's Party, etc.) than for the majority of Eurosceptic parties.

This finding supports a claim that only recently – after decades of scholarly emphasis on anti-EU mobilization – has been introduced in the literature (Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2020): perhaps as a reaction to the rise of Eurosceptic parties, nowadays also pro-European parties mobilize voters on EU issues. This means that the impact of EU positional distance has spread across the entire EU political spectrum, affecting the electoral preferences for both anti-EU and (even more) pro-EU parties. Therefore, our H3 has found an empirical backing and we are allowed to maintain that the EU distance matters on the likelihood to vote for both Europhile and Eurosceptic parties.

Models 7 and 8 test the moderating effect of salience measures on the EU issue voting for different party profiles. By interacting EU Twitter salience with EU distance and EU party ideology (Europhile versus Eurosceptic), the coefficient is positive and significant (1.821). However, when plotting this interaction term, Figure 5 shows that the level of EU issue voting has remained constant across the different values of EU Twitter salience for both Eurosceptics and Europhiles. Again, this result contradicts the notion of Twitter having a mobilizing effect over European integration.

Figure 5. Average marginal effects of EU distance by EU party ideology and EU Twitter salience (95% CIs).

As for the moderating role of the EU CHES salience, also in this case we included a three-way interaction between this measure, EU distance and EU party ideology (model 8). Figure 6 plots the average marginal effects showing that the moderating power of CHES salience can be confirmed for both party profiles. Indeed, the likelihood to vote for (Eurosceptic and Europhile) parties based on EU positional closeness has been multiplicated by the salience parties have attached to the EU. More importantly, the upper values of EU CHES salience (those varying from 0.58 to 0.91) hold more significant multiplicative effects on the likelihood to vote for Europhile parties rather than for Eurosceptic ones. This test suggests a greater electoral profitability of emphasizing the EU for pro-European parties, a finding that resonates well with the latest research in the field proving a more confrontational strategy on the side of Europhiles in the recent past (Braun and Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021; Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021). In brief, by emphasizing the EU, pro-European parties have become more likely to attract voting preferences than Eurosceptic parties. This finding contradicts previous contributions arguing that Eurosceptics hold more incentives to prime EU issues than Europhiles (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). Several factors may have contributed to this dynamic of Europhile party-voter alignment, certainly the outcome of the Brexit referendum provided these parties with new strategic incentives to politicize the EU conflict their own way (De Vries, Reference De Vries2017; Carrieri, Reference Carrieri2020).

Figure 6. Average marginal effects of EU distance by EU party ideology and EU CHES salience (95% CIs).

Conclusions

According to several scholars, the European integration process has played an important role in affecting voting choices at the EP elections, to the point of bringing to evidence the phenomenon of EU issue voting (Jurado and Navarrete, Reference Jurado and Navarrete2021). We have inserted our work in the same literature and offered an updated analysis of how much the EU conflict has contributed to determining the electoral preferences in the national elections of five countries in the 2017–2018 period.

This article has provided a detailed analysis about the relation between the EU party-voter distance and the voting preferences. We tested whether the electoral support of political parties was influenced by EU positions and by the salience that parties assigned to the EU. Our research provides a detailed demand-supply analysis (measured in terms of voting preferences and party-voter positional distances) of the influence of the EU issue on national elections. It is innovative since it is based on the empirical analysis of data gathered from various sources (public opinion surveys, Twitter, CHES expert surveys) that have never been used before in such triangulation to test the same kind of hypotheses linking mass and party levels.

Our empirical findings show that the EU positional distance is a significant factor in determining the electoral support for parties: the smaller the EU distance between a voter and a party, the more likely is the propensity of the same voter to support that party. These results may be generalized across all the countries under study where the EU issue systematically affects the electoral potential of parties.

At a more specific level, another original finding of our work is related to what we may define a ‘Pro-EU mobilization’. In this respect, we demonstrated that the effects of the EU issue have been more significant in influencing the electoral preferences of pro-EU parties. While an overwhelming body of literature has illustrated the powerful effects of anti-EU mobilization in the past few decades (De Vries and Hobolt, 2016), we show how in more recent years voters have also become significantly mobilized in support of Europhile parties. Thus, we can draw from our study the following generalized lesson: the effects of the EU positional distance have spread across the whole political spectrum, influencing the PTVs of both Eurosceptic and pro-European parties.

This work has also examined if the salience assigned by parties to the EU has increased EU issue voting. We combined different sources of salience and, in the end, the moderating effects of EU salience are mixed. On the one hand, the EU Twitter salience does not hold any significant influence on the relationship between EU positional distance and the PTV for different parties. Even if we do not question the importance of social media in contemporary party communication (D'Alimonte et al., Reference D'Alimonte, De Sio and Franklin2020; Stier et al., Reference Stier, Froio and Schünemann2021), this evidence may suggest that the Twitter mobilizing effect on the EU is not able to reach a broad audience, thus it is not as significant as some may expect in mobilizing the electorate on the EU. On the other hand, higher levels of EU salience – as documented by CHES – significantly enhance the effects of EU positional distance on voting preferences. This finding seems to suggest that it is important for parties to adopt a wide-range of communication strategies across many different arenas and media outlets to mobilize voters on the EU, rather than investing on Twitter as their primary promotional strategy. Importantly, the EU CHES salience holds more significant moderating powers on the EU issue voting for the Europhile parties (though it shows a similar direction for both party types). Europhile parties have probably become more willing to collide on the EU issues with the Eurosceptics (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Braun and Grande, Reference Braun and Grande2021), gaining as a result electoral benefits on this issue dimension.

We were able to confirm the relative autonomy of EU positional distance and EU salience as voting determinants controlling for other distance variables (i.e. immigration, economic redistribution, left-right). This step in the analysis allowed us to demonstrate the primary importance of EU issues at the electoral level, not a subsidiary parcel within a new system of conflicts dominated by migration, but a fully-fledged driver behind electoral mobilization. Since we focused on the 2017–2018 general elections, we were able to draw evidence about the very nature of the party-voter linkage based on the EU, not as a mere outgrowth of the EP elections. The electoral pattern that has emerged from our research definitely appears to reflect a stable phenomenon rather than a more erratic dynamic depending on the electoral arena (European vs. national elections). Thanks to this evidence, we can reject the argument about the EU issue having only limited observable effects on national elections and conclude that a fully-fledged party-voter linkage on the EU exists, with European integration playing a significant role in relation to the voting preferences in first order national elections. In our view, this overall evidence vindicates the theoretical argument about the ascendance of EU issue voting and provides solid empirical results about its incidence in the EU member states.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2023.1

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.