Introduction

In its official rhetoric, the European Union (EU) consistently portrays itself as an international actor committed to using trade agreements as tools to promote sustainable development, particularly in the context of its trade relations with developing countries (European Commission, 2006, 2012, 2015). Given the EU's pivotal role in international trade relations, this strategy has the potential to contribute to effectively promote sustainable development practices around the globe, but also to increase popular support for an open international trading system in the EU itself (Bastiaens and Postnikov, Reference Bastiaens and Postnikov2019).

However, this solidarity-based discourse rests on weak empirical foundations (Young and Peterson, Reference Young and Peterson2014; Smith, Reference Smith, Khorana and Garcia2018). While sustainable development provisions have become an integral part of the EU's ‘new generation’ trade agreements (Van den Putte and Orbie, Reference Van den Putte and Orbie2015), several empirical works show that the design of these provisions within the Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs), with developing countries, varies significantly, particularly with regard to their degree of bindingness, enforceability, and transparency (Adriansen and Gonzàlez-Garibay, Reference Adriansen and Gonzàlez-Garibay2013; Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2018; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Barbu, Campling and Smith2019).

PTAs are agreements that liberalize trade between two or more countries without extending this liberalization to all countries (Dür and Elsig, Reference Dür and Elsig2015). In some of the PTAs signed by the EU with developing countries, sustainable development provisions are unequivocally binding, rendered enforceable through the creation of a dispute settlement mechanism, and include transparency measures that ensure public oversight over their implementation. In other instances, the way in which these provisions are formulated contributes to significantly watering down their binding force, while enforcement mechanisms and transparency measures are weak or absent altogether (Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2018). This means there are significant differences not only in the way the EU promotes sustainable development through trade with respect to other major trading players (Postnikov and Bastiaens, Reference Postnikov and Bastiaens2014, Reference Postnikov and Bastiaens2020; Postnikov, Reference Postnikov2019) but also in the way in which the EU itself approaches different developing countries.

What factors drive this observed variation? Traditional arguments on the EU's role as a global regulator through trade are ill-equipped to account for this empirical observation. Studies that conceive the EU as a normative trade power, i.e. as an actor that is structurally bound to promote norms and values beyond its borders through trade (Manners, Reference Manners2002; Lucarelli and Manners, Reference Lucarelli, Manners and :2006; Scheipers and Sicurelli, Reference Scheipers and Sicurelli2007; Khorana and Garcia, Reference Khorana and Garcia2013; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch, Biukovic and Potter2017) have difficulties coming to terms with this inconsistent approach towards developing countries. Accounts focusing on the EU's role as an actor that uses its market size to externalize its domestic regulatory policies (Damro, Reference Damro2012; Young, Reference Young2015) also have problems explaining why sustainability provisions vary in cases marked by similar market power asymmetries. Finally, arguments focusing on the domestic political–economic foundations of EU international regulatory strategies face similar difficulties. While it has been convincingly shown that EU often exports regulatory standards through trade agreements to satisfy the demands of organized domestic producers wishing to impose costly regulatory burdens onto foreign competitors (Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2010; Kelemen and Vogel, Reference Kelemen and Vogel2010; Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2016), it is unclear why these incentives should vary across different developing countries that equally expose the least competitive sectors in the EU to imports from labor-abundant countries.

We contend that this variation can be made sense of by integrating this latter standard ‘regulatory politics’ argument with a discussion on how the growing integration of the EU economy with particular subsets of developing countries in global value chains (GVCs) affects the domestic politics of regulatory export through trade agreements. The increasing integration of the EU economy in GVCs means that there are a growing number of European firms that rely on imports of finished products or intermediate inputs produced in low-labor cost developing countries. These European import-dependent firms can be expected to oppose the export of those regulatory burdens that are more likely to generate an increase of their imports' variable costs, i.e. costs related to transportation, insurance, fees, tariffs, and regulations. When the EU engages in trade negotiations with developing countries with which it is highly integrated into GVCs, these import-dependent firms will mobilize politically to avoid the inclusion of labor and environmental provisions that will entail negative distributive consequences for them (Eckhardt and Poletti, Reference Eckhardt and Poletti2016). This, in turn, changes the domestic political constellation traditionally underpinning the politics of regulation through trade agreements. By weakening domestic coalitions supporting PTA-led regulatory export, this dynamic explains why the EU adopts a more lenient regulatory approach on sustainable development provisions in PTA negotiations with particular sets of developing countries.

We illustrate the plausibility of this argument by comparing the politics of EU regulatory export in the context of PTA negotiations with different sets of developing countries mainly including lower–middle income countries: the Andean Community (AC), the Caribbean sub-group of the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries (CARIFORUM), and Vietnam. Consistently with our factor-centric research design, these case studies have been selected because they provide for the needed variance on the side of the explanatory conditions, i.e. different degrees of GVC integration, while, at the same time, allowing us to keep constant and control for important exogenous potential sources of variation. Using a combination of congruence testing and process tracing, we (1) provide evidence of varying degrees of GVC integration between the EU and these countries, (2) show that different degrees of integration of EU trade partners in GVCs stimulated different patterns of political mobilization of import-dependent firms opposing the inclusion of labor and environmental provisions in these trade agreements, and (3) demonstrate how these different constellations of domestic political conflict lead to different treaty provisions on sustainable development.

Existing arguments

The observation that labor and environmental provisions vary significantly across different trade agreements signed between the EU and different developing countries (Baccini et al., Reference Young and Peterson2014; Young and Peterson, Reference Young and Peterson2014; Van den Putte and Orbie, Reference Van den Putte and Orbie2015) challenges three sets of established explanations for the EU's role as a global regulator through trade. For one, this observation is problematic for arguments pointing at the allegedly normative character of the EU trade policy (Manners, Reference Manners2002; Lucarelli and Manners, Reference Lucarelli, Manners and :2006; Scheipers and Sicurelli, Reference Scheipers and Sicurelli2007; Khorana and Garcia, Reference Khorana and Garcia2013; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch, Biukovic and Potter2017). If it is true that the EU is structurally bound to promote norms and values beyond its borders through trade, then we should expect it to consistently promote labor and environmental standards across the board.

An alternative approach focuses on the EU's role as a market power, contending that the large size of the EU's market allows it to externalize, intentionally or unintentionally, its domestic regulatory policies (Damro, Reference Damro2012). This view suggests that observed variation in the design of sustainable development provisions could be a function of differences in the distribution of market power between the EU and its trading partners (Young, Reference Young2015). While this is a powerful explanation in general, it is hardly applicable to the cases considered here, i.e. cases in which the differences in terms of levels of socio-economic development and market size between the EU and its developing trading partners do not vary substantially.

A different set of studies suggest that the reasons for driving the EU's willingness to export labor and environmental provisions lie in the economic interests of key domestic constituencies in the EU. According to this view, including sustainability provisions in trade agreements serves the purpose of exporting costly environmental and labor standards that would raise production costs for producers located in developing countries, thereby reducing their competitive advantage over producers and workers employed in labor-abundant sectors in the EU (Raess et al., Reference Raess, Dür and Sari2018).

This line of argument has the important advantage of specifying the domestic political–economic foundations of EU regulatory export strategies through PTAs, yet in its current formulation, it provides little guidance in shedding light on why in the negotiations with labor-abundant countries such as Vietnam, the EU tends to adopt softer strategies of norm promotion than in the negotiations with other developing countries.

GVCs and the politics of sustainable development in trade agreements

When it comes to deriving preferences over regulatory export strategies, political-economy approaches usually share many features of traditional models of trade policy. These models typically assume that policymakers act as transmission belts for the demands of organized domestic societal groups and rely on the key distinction between import-competing and export-oriented sectors (Hiscox, Reference Hiscox M2001; Dür, Reference Dür2008). Producers and workers in import-competing sectors fear trade liberalization because of the increased import-penetration from more efficient foreign producers and, by extension, they should favor the inclusion of stringent labor and environmental standards in trade agreements because of their potential to curb import and wage pressures by limiting the competitive advantage of foreign producers (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Dür and Lechner2018; Raess et al., Reference Raess, Dür and Sari2018). Export-oriented sectors are not directly affected by the inclusion of a regulatory provision in trade agreements, but they can be expected to oppose discussions about political issues that may create an impasse in the negotiations they support (Lechner, Reference Lechner2016).

While standard political economy approaches to EU trade policy have traditionally overlooked the role of NGOs, assuming their inability to overcome collective action problems (Poletti and De Bièvre, Reference Poletti and De Bièvre2014), more recent studies show that they can play a key role in the politics of trade (Young and Peterson, Reference Young and Peterson2006; Pollack and Shaffer, Reference Young and Peterson2009; De Ville and Siles-Brügge, Reference De Ville and Siles-Brügge2015). These studies highlight that both a high probability of obtaining the desired policy goal (e.g. when regulatory issues are at stake and when trade negotiations become politicized) and the effective use of organizational selective incentives exist, can act as powerful triggers for the political mobilization of these diffuse interests. And since these groups consistently favor the international diffusion of labor and environmental standards, they tend to form Baptist Bootlegger coalitions with import-competing groups with a view to supporting offensive international regulatory strategies (DeSombre, Reference DeSombre2000; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2010; Kelemen and Vogel, Reference Kelemen and Vogel2010; Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Young and Peterson2012, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2016; Hannah, Reference Hannah2016). This means that NGOs acting on behalf of genuine concern for developing countries' well-being often support sustainable development in coalition with import-competing producers driven by a desire to curb these countries' export potential.

This traditional view, however, overlooks the importance of ongoing processes of globalization of production and distribution, resulting in the emergence of GVCs. While in the past retailers and producers in advanced economies bought or produced the bulk of their products and inputs domestically, since the 1990s, many retailers and producers started to outsource labor-intensive, less value-added operations to lower-income countries (mainly in Asia) while retaining the highest value-added segments of manufacturing and services (Elms and Low, Reference Elms and Low2013; OECD et al., Reference Young and Peterson2013). These processes have been carried out through the creation of foreign subsidiaries (i.e. vertical foreign direct investment) or by relying on independent foreign suppliers (Lanz and Miroudot, Reference Lanz and Miroudot2011). The EU is a central player in these GVCs, both because of the magnitude of its foreign production linkages and because of the increasing importance of regional value chains (Amador and Di Mauro, Reference Amador and di Mauro2015).

A growing number of studies have focused on the implications of GVCs for EU trade policy showing that the latter has become more responsive to the preferences, patterns of political mobilization, and influence of import-dependent firms, that is firms and sectors that rely on income generated from the import of intermediate products for their production process. These contributions show that import-dependent firms have increased the weight of the domestic coalition favoring trade liberalization in the EU (Eckhardt, Reference Eckhardt2015; Eckhardt and Poletti, Reference Eckhardt and Poletti2016; Yildirim, Reference Yildirim2016; Smith, Reference Smith, Khorana and Garcia2018; Dür et al., Reference Dür, Eckhardt and Poletti2020).

An important contribution by Lechner (Reference Lechner2016) on the design of PTAs suggests that import-dependent firms can play a key role in the domestic politics of regulatory export too. These firms, be they vertically integrated multinational corporations (MNCs) or importers relying on independent foreign suppliers, accrue benefits by accessing cheap imports (Manger, Reference Manger2012). If this is true, by extension, they can be expected to oppose the inclusion of labor and environmental standards in trade agreements. For one, the decision by European import-dependent firms to either locate production or rely on imports of intermediate inputs produced abroad is mostly driven by low costs in these host countries' factor prices (Chase, Reference Chase2003). As Lechner (Reference Lechner2016: 10) notes, ‘reducing flexibility in hiring-and-firing policies, guaranteeing a minimum wage, improving safety standards, allowing workers to strike, or applying environmentally friendly policies involves costs for business.’ While import costs-related concerns are certainly more pronounced when import-dependent firms heavily rely on subcontracting and arm's length relationships with suppliers (Mosely, Reference Mosley2011), they also significantly affect vertically integrated MNCs in general, and primarily those operating in polluting and low-skilled labor endowed industries (Lechner, Reference Lechner2018; Malesky and Mosley, Reference Malesky and Mosley2018). Moreover, import-dependent firms can be expected to oppose labor standards not only to keep labor costs low but also to avoid supply chain disruptions caused by workers organization and mobilization (Anner, Reference Anner2015).

To be sure, import-dependent firms sometimes have to take into account the potential reputational costs associated with being seen supporting low labor or environmental standards in developing countries. Yet, these reputational concerns play a significant role only in a small number of instances, particularly in the case of branded or luxury goods-producing firms that can be more easily targeted by activists (Vogel, Reference Vogel, Mattli and Woods2009; Malesky and Mosley, Reference Malesky and Mosley2018). Moreover, these firms often do not lobby individually but do so through broad sectoral associations (Poletti et al., Reference Poletti, De Bièvre and Hanegraaff2016), which allows them to minimize the visibility of their lobbying activity, hence their reputational concerns. So, while import-dependent firms favor trade liberalization via PTAs they should also be expected to broadly oppose the inclusion of costly regulatory burdens that may contribute to increasing the variable costs of their imports.

Taking into account the role of GVCs and EU import-dependent firms operating within them accounts for the observed differences in EU regulatory export strategies through PTAs. When the EU negotiates trade agreements with developing countries with which it is weakly integrated into GVCs we should expect the political role of import-dependent firms to be limited. In light of the strong preferences of import-competing firms in favor of sustainable development provisions, who can also count on the backing of NGOs, and the only marginal opposition of export-oriented firms towards these provisions, it is likely that the EU trade agreements with these countries will include far-reaching and stringent labor and environmental provisions. Conversely, when the EU negotiates trade agreements with developing countries with which it is highly integrated into GVCs, we can expect import-dependent firms to play a significant political role, widening the domestic political coalition opposing these regulatory export strategies. In this case, the domestic coalition supporting sustainability provisions faces a stronger counter-coalition of import-dependent firms and export-oriented ones, making it more likely that these trade agreements, other things being equal, will include less far-reaching and less stringent labor and environmental norms.

It is important to note that while our argument primarily sheds light on the dynamics that underpin the politics of preference formation in the EU, the broad statements we formulated above implicitly extend our argument's scope to negotiation outcomes. We do so because we deem it highly plausible that in the particular context of trade negotiations with developed countries bargaining outcomes with respect to sustainable development provisions should closely reflect underlying EU policy preferences. In general, the large size of its domestic market confers the EU a huge bargaining power in trade negotiations because of the costs that its trading partners are willing to incur to gain access to it (Dür, Reference Dür2010; Damro, Reference Damro2012; Dür et al., Reference Dür, Eckhardt and Poletti2020). This is even more true in the case of negotiations with developing countries. For one, gaining access to the large EU export market is often of vital importance for these countries, something that is likely to make them prone to accept the negotiation terms dictated by the EU (De Bièvre and Poletti, Reference De Bièvre, Poletti, Falkner and Müller2014). Moreover, these negotiations are characterized by a high degree of economic power asymmetry, another important source of bargaining power for the EU (Sattler and Bernauer, Reference Sattler and Bernauer2011). For these reasons, we deem it safe to draw a direct connection between EU preferences and bargaining outcomes without systematically integrating EU trading partners' agency within our argument.

Empirical illustration

In order to show the plausibility of our argument, we look into three trade agreements concluded by the EU since 2008 with (1) CARIFORUM, (2) the AC, and (3) Vietnam. Consistently with our factor-centric research design, the case studies have been selected to provide for the needed variance on the side of the explanatory conditions. As we show below, these trading partners differ significantly in terms of how much they are integrated with the EU in GVCs, with Vietnam displaying the higher level of integration, the AC an intermediate level, and CARIFORUM the lowest.

At the same time, our case selection allows us to keep constant and control for important exogenous, potential sources of variation. First, all EU trading partners considered are developing countries, namely countries towards which the EU has explicitly and consistently committed to promoting sustainable provisions throughout time. Second, the differences in the distribution of market power between the EU and the considered developing trading partners are not large enough to make it plausible that they can be a major driver of observed variations in the design of sustainable development provisions. Third, and differently from other recent EU trade negotiations (e.g. the negotiations with the US and Canada), the negotiations we consider were characterized by similar relatively low levels of saliency and politicization. This enables us to control for the potential effects of different degrees of politicization on the extent to which EU trade policymakers can give in to the demands of business groups without facing a backlash. Fourth, the decision-making rules for the adoption of these trade negotiations do not vary systematically. While, in contrast to negotiations with Colombia, Peru, and Vietnam, negotiations with the CARIFORUM preceded the adoption of the Treaty of Lisbon granting veto power to the European Parliament (EP), they were embedded in the peculiar Economic Partnership Agreements' (EPAs') institutional framework, which already required the consent of the EP.

Finally, where our case studies do display significant variation in terms of relevant country-level characteristics, i.e. levels of domestic labor and environmental standards, they help us make stronger claims about the validity of our argument. Vietnam is the country that displays the worst scores on both labor and environmental standards amongst the ones we analyze (Wendling et al., Reference Wendling, Emerson, Esty, Levy, de Sherbinin and Mardel2018; Kucera and Sari, Reference Kucera and Sari2019) and on the basis of traditional regulatory politics arguments, this should translate in the strongest pressures to include sustainable development provisions in PTAs. This makes Vietnam the least likely case for our argument.

Using a combination of congruence testing and process tracing, the next sections show that: (1) the EU and the different developing trading partners considered are characterized by different levels of integration in GVCs; (2) high (low) levels of integration in GVCs triggered high (low) levels of political mobilization of organizations representing the interests of import-dependent firms, and (3) the political mobilization of import-dependent firms carried significant weight in the EU's trade policy-making process.

Differences in levels of integration in GVCs

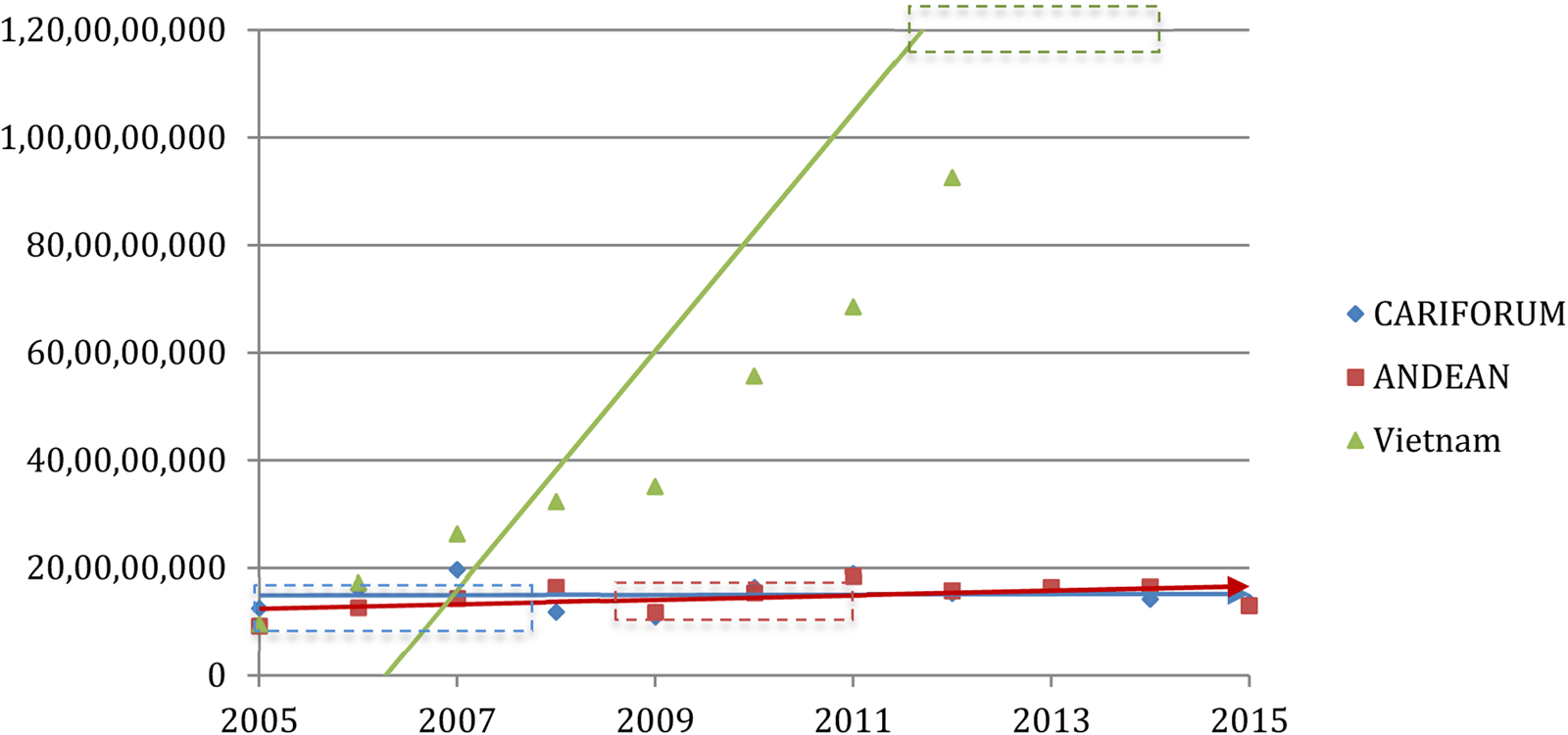

We first present evidence of varying degrees of integration in GVCs between the EU and its developing trading partners. To do so, we rely on two datasets and three different measures. In Figure 1, we make use of the OECD/WTO trade in value added (TiVA) dataset. Unfortunately, the TiVA dataset is limited in its country coverage. To alleviate this shortcoming, we also rely on the United Nations (UN) COMTRADE dataset (see Figures 2 and 3).Footnote 1 The figures are presented with marked values as well as trend lines in order to make it easier for readers to see how the values change over time. We also added dotted boxes in each figure that indicates the negotiation period for each agreement under study.

Figure 1. How much PTA partners add value to the products exported from the EU? (USD in total EU exports). Figure indicates foreign value added embodied in European Union exports by Vietnam and two AC members (i.e. Peru and Colombia), as well as total imports from CARIFORUM members. OECD TiVA added dataset used for Vietnam, Peru, and Colombia values. Total imports from CARIFORUM are calculated from UNCOMTRADE.

Figure 2. EU imports in retail products from selected trade partners (real values in USD). Figure indicates the value of European Union imports of retail products in USD, i.e. food and beverages, footwear, and textiles, from its trade partners. The values are calculated from UNCOMTRADE.

Figure 3. EU imports of intermediate products from selected trade partners (real values in USD). Figure indicates the value of European Union imports of intermediate GVC products from its trade partners, including over 800 products classified by the UNCOMTRADE under GVC inputs. The values and the classification can be found via World Integrated Trade Solutions and UNCOMTRADE.

We start by presenting the results from the TiVA dataset in Figure 1. The graph indicates the share of value-added (in real terms) by the AC (Peru and Colombia), as well as by Vietnam for products that are further processed and/or exported from the EU. For CARIFORUM members, we do not have value-added trade data, and we decided to use values of total trade to give an idea of the volume handled by these trade partners relative to the AC and Vietnam. Vietnam's value-added in EU exports is significantly higher than that of the AC, increasing from USD 8 billion in 2005 to around USD 11 billion in 2015. This means that as part of the entire exports of the EU, standing around USD 4 trillion in 2015, Vietnam's contribution was around USD 11 billion. On the other hand, we see the combined value-added of the AC is around USD 8 billion during the period under study. Total imports from CARIFORUM into the EU average at USD 5 billion between 2005 and 2015, which exaggerates value-added but even then, stands below the AC's and Vietnam's value-added.Footnote 2

Given the limited country coverage of the TiVA dataset, we provide further evidence of differences in EU PTA partners' GVC integration. Figure 2 presents a comprehensive view of the EU's import-dependence in the retail sector. Following Eckhardt and Poletti (Reference Eckhardt and Poletti2016), we focus on the manufacturing of food and beverages, footwear, and textiles, which are goods typically imported by retailers. The results are in line with previous evidence, showing that imports from Vietnam are significantly higher than any other EU partner in our study – followed by the AC and CARIFORUM.

Finally, Figure 3 provides evidence of EU's imports of intermediate products, i.e. input products that are further processed for final goods and services. Here we rely on the UNCOMTRADE data based on harmonized system classification of intermediate GVC products, referring to over 500 6-digit products ranging from apparel to electronics.Footnote 3 We observe again that EU imports of intermediates from Vietnam are much higher than those from CARIFORUM and the AC, valued over USD 1 billion after 2011, while intermediate imports from CARIFORUM and the AC remain roughly constant over time (at about USD 100 million).

Overall, this descriptive evidence lends support to the view that Vietnam is the trading partner with which the EU is relatively more highly integrated into GVCs, CARIFORUM the one with which is the least integrated, while the AC is positioned somewhere in between.

Patterns of political mobilization by trade-related interests

A comparison of the patterns of political mobilization underlying trade negotiations with CARIFORUM, the AC, and Vietnam shows that while each trade deal triggered the political mobilization of traditional trade-related interests, i.e. exporters, import-competitors, and NGOs, the political role of import-dependent firms was particularly relevant in the case of Vietnam.

EU–CARIFORUM agreement (2008)

The EU and the CARIFORUM group launched the EPA negotiations in response to the ruling of the WTO against the EU's preferential trade scheme with the ACP countries, in 1997. Following this ruling, the negotiations with CARIFORUM took shape in the legal framework of the EU–ACP Cotonou agreement (2000) and started in 2004.

The negotiations with the CARIFORUM mostly mobilized import-competing farmer organizations and NGOs. Pressures from these organizations are not particularly surprising, since the EU represents the second largest destination of Caribbean agricultural export after the US. In particular, the pressures to lower European tariff barriers of Caribbean exporters of tropical commodities such as sugar and bananas and also rice (Weinhardt and Moerland, Reference Weinhardt and Moerland2018) raised defensive positions among French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and also Polish farmer organizations (Poletti and Sicurelli, Reference Poletti and Sicurelli2018).

The Stop EPA movement originated in 2004 complained about the lack of attention of the negotiators for development implications of negotiations, although later on, it ended up adopting a more pragmatic and reformist stance (De Felice, Reference Del Felice2012). As a result, the movement joined a coalition of trade unions, environmental NGOs (FOE 2006), and even farmer organizations sharing support for the negotiations under the condition that they would address the concern for the implications of the agreement for sustainable development and would include binding and enforceable labor and environmental clauses. An example of cooperation between NGOs and agriculture interest groups can be found in the banana sector. Firms involved in the banana production joined the demands of environmental NGOs for limiting the use of pesticides consistent with the EU's own strict pesticide standards (LaForce, Reference LaForce2014).

Exporter interests represented by Eurochambers only mobilized to get access to the Dominican Republic's market equal to what the US had obtained in a 2004 agreement (Faber and Orbie, Reference Faber, Orbie, Faber and Orbie2009), while import-dependent groups were altogether absent from the negotiations. An official in charge of the negotiations with CARIFORUM recalled that they never submitted any request to the European Commission (interview, Directorate General (DG) trade, June 2017).

The EU–AC trade agreement (2011)

The EU started negotiating with AC countries in 2007 following the launch of US trade negotiations with those countries in order to address European exporters' concerns for potential losses in terms of market access in the region. The negotiations had a wide echo in the European civil society concerned for the potential labor, environmental, and human rights implications of the agreement. The European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) was especially vocal (ETUC 2006, 2008, 2009) and joined European NGOs in building a network with their counterparts within the AC (interview, ETUC, July 2017, Brussels), as well as with advocacy groups, including the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) (ETUC and ITUC 2010), the International Federation on Human Rights (FIDH 2012), the International Office for Human Rights – Action on Colombia (OIDHACO 2010), and the Transnational Institution (Fritz, Reference Fritz2010). These organizations pushed for the inclusion of binding and enforceable sustainable development provisions in the agreement.

Differently from the case of EU–CARIFORUM negotiations, protectionist organizations were less aligned with NGOs, as the agricultural exporting capacity of Colombia and Peru is relatively limited and many of their agricultural exports (tropical fruit, counter-seasonal fruits, specialist grains) are not in direct competition with the EU agricultural sector (European Parliament, 2016).

Instead, and despite the low levels of total EU exports in the AC, these negotiations did trigger some mobilization of exporters' interests represented by Eurochambers (2012), especially in the services sectors (telecommunications, construction, distribution, finance, and transports). Finally, the AC countries generated relatively low levels of mobilization of import-dependent groups, since they mainly export raw materials (such as mineral products, agricultural products, beverages and tobacco, foodstuffs, animal and vegetable fats) or semi-transformed goods with little added value (Eurocommerce, 2007a, 2007b). For these reasons, both organizations representing exporters (UNICE 2006; European Services Forum, 2011; BusinessEurope, 2012) and import-dependent firms (Eurocommerce, 2007a) supported the conclusion of these agreements but did not express concerns that the inclusion of binding sustainable development provisions could end up stalling negotiations.

EU–Vietnam agreement (2015)

The EU launched negotiations with Vietnam in 2012. Exporters in service sectors such as insurance and banking sector mobilized strongly to promote this trade agreement (Dreyer, Reference Dreyer2015). Yet, what made negotiations with Vietnam different from those with the CARIFORUM and AC countries was the activism of organizations representing import-dependent firms (Eurocommerce, 2007b, 2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2012; FTA, Reference Young and Peterson2012). The EU is the main destination of Vietnamese exports in goods, which attracted European retailers and import-dependent interests (Eckhardt and Poletti, Reference Eckhardt and Poletti2016).

Import-dependent interest groups manifested their support for the trade agreement, explained their support for voluntary initiatives of their members in the framework of corporate social responsibility rather than for binding standards, and contextually commented that ‘trade policy should not be linked with social or environmental standards’ (Eurocommerce, 2007b). Eurocommerce (2010a) more explicitly warned that the inclusion of those standards in the trade agreement ‘would risk to be instrumentalized for protectionist purposes’. In order to affect the negotiations, Eurocommerce and Foreign Trade Association (FTA) created a stable mechanism of coordination of their lobbying activities (Eckhardt and Poletti, Reference Eckhardt and Poletti2016).

Similar to the negotiations with the CARIFORUM, both civil society organizations (ETUC 2010, 2012b; Fidh, 2013) and protectionist industries in the textile, footwear, rice, and fishery sectors engaged in promoting high-sustainability standards in the agreement. Yet, these sectors, especially the textile and footwear, were characterized by internal divisions, with import-dependent industries within them seeking to challenge the defensive stance of import-competing firms (Euratex, 2010; Assocalzaturifici, interview, July 2014).

The impact of interest groups mobilization on the trade agreements

In this section, we seek to trace the influence of interest groups and NGOs on the EU negotiating position and show how variation in the content of trade agreements is driven by the causal mechanisms we postulate. While in each sub-section, we discuss some of the sustainable development provisions included in the different trade agreements, for the sake of clarity, we provide a summary overview of such provisions in Table 1.

Table 1. Sustainable development provisions in the trade agreements with CARIFORUM, AC, and Vietnam

EU–CARIFORUM agreement

Evidence suggests that pressures of import-competing groups and NGOs significantly affected the European Commission's negotiating position. Demands for higher sustainability standards ended up finding support especially in the United Kingdom, Denmark, France Sweden, the Netherlands, and Ireland (Interview, DG development, Brussels, September 2008, Interview, DG trade, Brussels, September 2008) also thanks to the fact that organizations representing European exporters and import-dependent firms were largely absent from the policy process.

The alliance between EU banana producers and environmental NGOs proved successful in persuading the European Commission to ask the Caribbean negotiators for the inclusion of stringent sanitary standards concerning the use of pesticides in the EPA (LaForce, Reference LaForce2014). More generally, the European Commission was able to obtain from CARIFORUM the most binding and detailed sustainability provisions of all the three agreements considered.

The conclusion of the EU–CARIFORUM EPA followed the publication of the Global Europe strategy of the European Commission (2006), which primarily aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the EU and devoted little attention to sustainable development. Despite this timing, the EU–CARIFORUM EPA clearly stands for its explicit commitment to establishing sustainable development as a principle governing the whole agreement (Moerland, Reference Moerland2013). The EU–CARIFORUM trade agreement is the only one that applies the general dispute settlement provisions of the agreement to trade controversies related to sustainable development. The dispute settlement contains transparency provisions. As article 216 states, ‘Any meeting of the arbitration panel shall be open to the public in accordance with the Rules of Procedure, unless the arbitration panel decides otherwise (…) or at the request of the Parties’. The agreement inaugurated the practice of including a transnational civil society forum (Orbie et al., Reference Orbie, Van den Putte and Martens2017), the CARIFORUM-EC Consultative Committee (article 231), as an instrument to ‘promote dialogue and cooperation between representatives of organizations of civil society’. The fact that the Dominican Republic had already agreed upon a similar mechanism in the context of the CAFTA-DR in 2005 facilitated the inclusion of the dispute settlement mechanism in the case of violation of labor and environmental norms (Kerremans and Gistelinck, Reference Kerremans, Gistelinck, Faber and Orbie2009). The Caribbean trade unions, NGOs, and small-to-micro-sized industries supported high-sustainability standards but complained about the lack of aid disbursement from the EU in support of those provisions (Byron and Lewis, Reference Byron and Lewis2007).

EU–AC agreement

In the case of the negotiations with the AC, the mobilization of European trade unions and NGOs interested in promoting stringent sustainability norms found a fully supportive EP (European Parliament, 2010; Bailey and Bossuyt, Reference Bailey and Bossuyt2013) and even reached national legislators such as German Bundestag (2010). Nevertheless, the lack of support for these demands in the business sector, due to the weak mobilization of protectionist interests, the pressures of service producers, and the mild activism of import-dependent firms, partially weakened the effectiveness of such advocacy coalition. It is for this reason that the EU simultaneously pushed for the inclusion of high labor and environmental standards while granting flexibility in terms of their enforcement (interview, ETUC, July 2017, Brussels).

More specifically, the EU–AC agreement entails the obligation to respect and effectively implement the fundamental ILO conventions and a number of multilateral environmental agreements and establishes a joint Trade and Sustainable Development subcommittee to monitor their effective implementation. According to article 267/7, the subcommittee shall promote transparency and public participation in its work. Yet, provisions concerning civil society monitoring in the agreement are less far-reaching than in other agreements (Orbie et al., Reference Orbie, Van den Putte and Martens2017). In contrast to the EU–CARIFORUM agreement, the EU–AC agreement does not establish a civil society forum (Leeg, Reference Young and Peterson2018), but it invites parties to ‘consult domestic labor and environment or sustainable development committees or groups, or create such committees or groups when they do not exist.’

EU–Vietnam agreement

A brief overview of the sustainable development provisions included in the EU–Vietnam trade agreement shows that, in line with our argument, these are the least stringent and enforceable ones across the three agreements considered.

The sustainable development chapter in the EU–Vietnam agreement calls on the parties to implement the ILO conventions and multilateral environmental treaties they have ratified and to ratify the other remaining conventions and treaties. In contrast to trade agreements concluded with the AC and CARIFORUM, the trade deal with Vietnam uses a ‘weaker language’ in the provisions concerning the sensitive sector of labor (Tran et al., Reference Young and Peterson2018, 4052): ‘each party will make continued and sustained efforts toward ratifying… core ILO conventions’ (article 3.3). The contracting parties will consider ‘the ratification of other conventions that are classified as up to date by the ILO, taking into account its domestic circumstances’ (article 3.4). Furthermore, and again in contrast to the other agreements, the trade deal with Vietnam does not formally establish a civil society forum. It establishes, instead, a forum ‘based on a balanced representation of economic, social and environmental stakeholders’ (articles 13–15). Article 15 of the chapter on Trade and Sustainable Development does foresee the meetings of domestic advisory groups, which ‘should include independent representative organizations of economic, social and environmental stakeholders’. The lack of legal recognition of independent NGOs and trade unions in the country, though, makes this clause hardly enforceable. It provides the two parties of the agreement with high discretion in shaping those advisory groups and states that ‘Each party shall decide on its domestic procedures for the establishment of its domestic advisory group or groups and the appointment of the members of such group or groups’ (article 13.15). Secondly, public transparency in the decisions and recommendations of the panel of experts is not guaranteed (Tran et al., 2018), because, unlike in the trade agreements with CARIFORUM and the AC, it is subject to a political decision of the parties. According to article 17.8, the sub-committee on sustainable development will decide whether to release its findings, calling the panel of experts to publicize its findings ‘unless the parties mutually decide otherwise’ (article 17.8).

In addition to the parallels between the demands of the organizations representing import-dependent firms reported in the previous section and the content of the sustainable development provisions included in the agreement, two other factors make it plausible that the pressures of organizations representing import-dependent firms did indeed influence negotiations. For one, both officials of the European Commission involved in the negotiations and members of the EP explicitly acknowledged that, in light of the high complementarity between the economies of the EU and Vietnam, European import-dependent interests proved particularly influential in defining the EU position in the negotiations with Vietnam (interviews, DG trade, January 2010, April 2010, and February 2013, member of the EP, august 2014). As a confirmation of these dynamics, a DG trade official commented that for the first time the EU obtained a highly reciprocal liberalization schedule from negotiations with a developing country (Borderlex, Reference Young and Peterson2015). Moreover, after the adoption of the agreement the FTA (FTA, 2016), in a report on ‘Free Trade, Sustainable Trade’, an important organization representing European import-dependent firms, expressed great satisfaction concerning the content of the agreement, with particular emphasis on the content of sustainable development provisions. According to the organization, the norms included in the chapter are sufficiently ‘comprehensive and binding’.

Conclusions

In this article, we have made a plausible case that observed variations in the sustainability provisions included in the trade agreements signed by the EU with different developing countries can be ascribed to their different degrees of integration in GVCs. More specifically, we presented evidence in support of the argument that high levels of integration between the EU and its developing trading partners in GVCs stimulate the political mobilization of import-dependent firms opposing the inclusion of stringent and enforceable sustainable development provisions that would entail negative distributive consequences for them in the form of increased variable costs of imports.

We illustrated the plausibility of this argument by way of a comparison of the EU domestic political dynamics underlying trade negotiations with different sets of developing countries: CARIFORUM, the AC, and Vietnam. Several implications of our article deserve attention. First, we contribute to the broader literature focusing on the domestic constellation of interests as the main drivers of the EU's behavior in trade governance – highlighting once again that the preferences of organized societal actors and their related patterns of political mobilization have an important causal role in EU trade policymaking. Far from wishing to advance the argument that organized societal actors alone drive EU trade policy, or that they consistently affect trade policy across time and space, we more modestly wish to underscore the importance of taking into account the domestic societal origins of EU trade policy preferences. Second, and within this context, our article shows that fully understanding the politics of regulatory export through trade agreements requires taking into account the interests and political role of import-dependent firms. While a growing number of works show that these groups are critical in supporting the elimination and/or reduction of traditional tariff barriers to trade, our analysis highlights that their political role extends to the politics of regulation through trade too. Finally, our findings contribute to the study of the EU as a norm promoter through trade by showing that the EU acts as a selective normative power, namely a trade power that is more likely to prioritize normative goals when doing so is compatible with the interests of its domestic producers.

Funding

Aydin B. Yildirim acknowledges the support of the European Union Horizon 2020 research programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement PROSPER No. 842868.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp. The raw data were collected from UNCOMTRADE and OECD TiVA datasets.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend theirs thanks to the editors for their assistance as well as to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.