INTRODUCTION

In August 1975, a group of youth militia leaders in the southeastern city of Kétou in Benin made a striking claim; they branded the politicians and administrators in the town, including those installed after Mathieu Kérékou's ‘revolution’, the coup d’état of 1972, as ‘neocolonialist’.Footnote 1 In doing so, they placed the officials responsible for local administration in an alleged continuity of scheming politicians from the 1960s and as successors of the colonial regime.Footnote 2 And that was only a relatively late (if extreme) example of such accusations. Throughout the 1960s, activists from the north of Dahomey, the future Benin, also regularly referred to the political elites in the south as ‘neocolonialist’, especially after the overthrow of the ‘northern’ president Hubert Maga in 1963 (they directed this accusation against southern elites both from Porto-Novo and Cotonou, and from the Abomey region in the southern interior).Footnote 3

The question of continuities from colonial into postcolonial forms of political rule and social organisation in African countries is, at first glance, something of an ‘old trope’. ‘Neocolonialism’ has been the target of the most variable forms of polemics, and has been appropriated by part of the (older) research literature.Footnote 4 Frederick Cooper questioned the helpfulness of the term, but historians have struggled to come up with a more adequate one.Footnote 5 Collusion and entanglements between new African elites and French officials can indeed be analyzed, at least on a case-by-case basis, and it is possible to discuss the objects of such analysis under the category of neocolonialism.Footnote 6 However, beyond the discussion about neocolonial entanglements, an even more important issue is the broader question of colonial heritage: influential studies, such as those of Mahmood Mamdani, have insisted on the essential importance of this continuity.Footnote 7 A significant problem concerns the source base and the depth of interpretation with regard to the continuity hypothesis: the argument has thus far mainly been theoretical.Footnote 8

I would like to analyse debates about and perceptions of ‘neocolonialism’ in southern and south central Dahomey from the moment of territorial autonomy in 1958 as a member state of the French Community, with much of the late colonial administrative apparatus still in place, to the first sustained military takeover in 1965. I will argue that discussions of continuities and neocolonialism appear at various levels, and that it is important to follow them and to analyze local reactions. As can be seen from the examples I highlight, it was possible for new political figures of the period to be involved at all levels of the discussion. Indeed, in this transition phase they could appear as top politicians, regional patrons, and members of development-related committees at the local level at the same time. The case of Justin Ahomadegbé, one of Dahomey's principal politicians of the period between the mid-1950s and 1972, shows the same person responding to concerns of problematic continuities from the colonial period in different contexts, and not always with the same arguments.

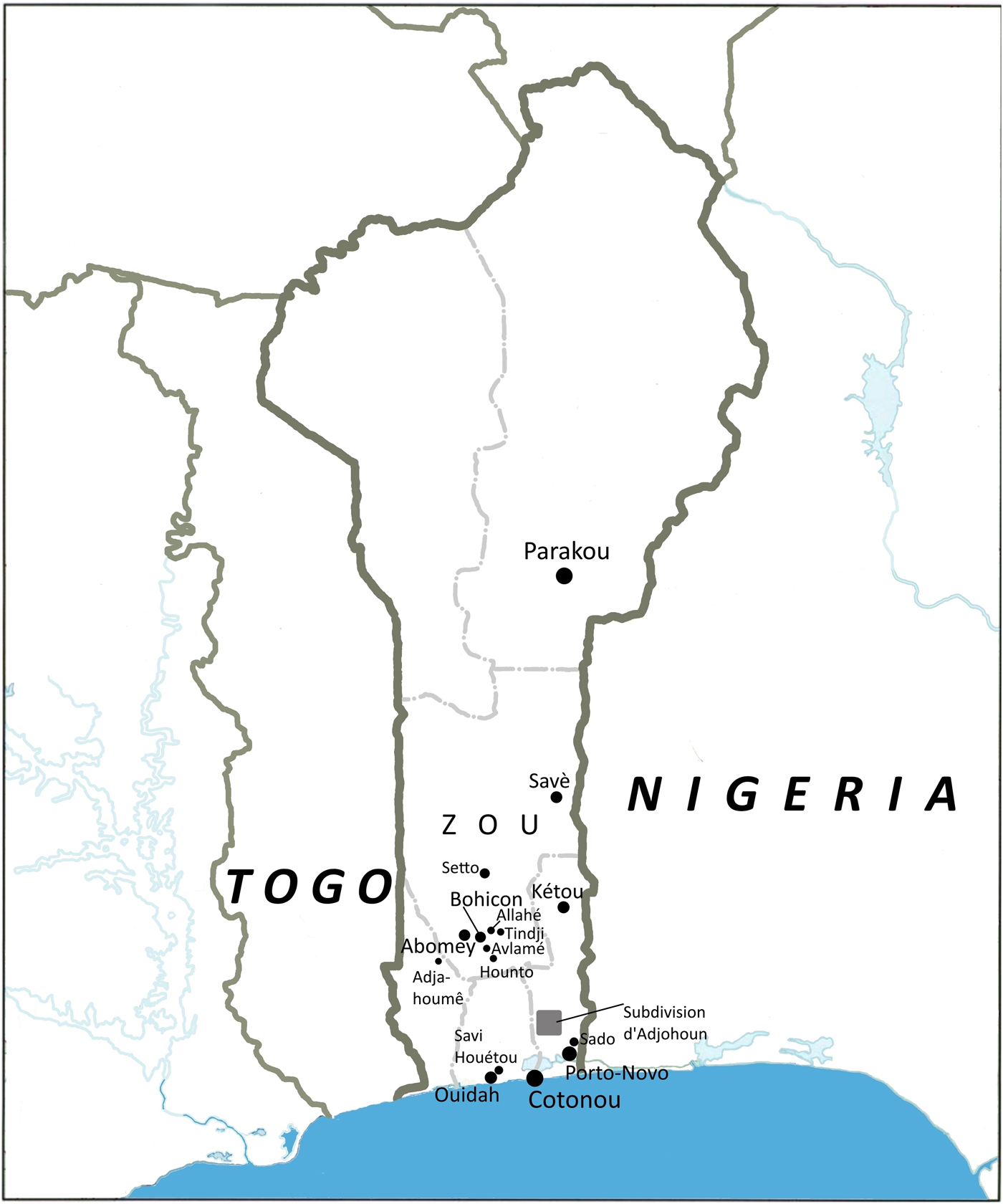

Fig. 1. Dahomey (Benin). This map profited from a map design that is courtesy of the Perry Castañeda Library of the University of Texas.

Despite the striking example of Ahomadegbé, it is not my intention here to make a contribution to Dahomean or West African elite biographies.Footnote 9 Certainly, Ahomadegbé is a remarkable figure whose life invites a biographical approach: he was a member of precolonial Dahomey's royal family in Abomey, albeit building his reputation on a reinvented past; he made a name for himself as a former graduate of France's prestigious administrative school for an African elite, William Ponty in Senegal, and practiced as a trained dentist in Porto-Novo. He became a politician from the period of political emancipation in 1945 onwards, was a councillor in the territorial assemblies, and a founding father and leader of the Union Démocratique Dahoméenne (UDD) associated with the trade union movement from 1955. After a phase of vigorous activity in opposition, Ahomadegbé was imprisoned in 1961/62, but was later freed and rehabilitated; he was installed as president of the council of ministers in 1964 after the first military coup of Christophe Soglo. Ousted from power and exiled in 1965, in a context of military and public anger against political blockade within the democratic government, he returned once more and became part of the triumvirate of three national leaders governing between 1970 and 1972, but was eventually put under house arrest for nine years after Mathieu Kérékou's coup d’état in 1972.Footnote 10 Ahomadegbé is interesting in terms of interactions with rural populations in the Abomey region, his particular political stronghold, as he cultivated (including with French observers) his image of being ‘a solid and good-spirited man of the land, a nationalist in the tradition of the Kingdom of Abomey, who is distrustful of foreign theories and utopias; he is little interested in the state of the soul of President Houphouët, the Negritude of Mr. Senghor or the Marxism of Mr. Sékou Touré; he speaks of ‘Cassava balls’, of bush routes, of village chiefs, and not of African socialism or internal conferences’.Footnote 11

However, in this article, Justin Ahomadegbé’s voice on continuities and neocolonialism is only one, albeit top-level, opinion. Rather than focusing on his views, I show that sentiments on ‘neocolonialism’ existed at the grassroots and in high politics at the same time.Footnote 12 They played a role in the responses of independent Dahomey's political leadership to trade union demands, in the organisation and perception of development projects at the regional level, and the reaction to tax exercises at the local level.

In the first example, the perspective I choose is indeed that of ‘high politics’, meaning here the discussion between trade union leaders and the president of the council of ministers. By 1964, Dahomean trade unions were fragmented but less neutralized than in other West African states.Footnote 13 Some union leaders managed to come to a consensus in order to challenge decisions specifically made under Ahomadegbé’s mandate in 1964. The debate is recorded in the detailed secret minutes of the meeting.

A second sphere in which individuals experiencing new policies evaluated them as ‘grassroots neocolonialism’ was that of advocating, discussing, and resisting agricultural ‘modernisation’. In southern Dahomey by 1958, such ‘modernisation’ meant not only the improvement of the palm fruit and palm oil sector, but also experiments with intensive rice cultures, tropical fruits, and coffee.Footnote 14 In the region of Porto-Novo, this led to complex debates about water distribution and use.Footnote 15 In the Abomey region, local political committees visited villages, made recommendations, and observed the local reactions.Footnote 16 One important question was the need for coercion. Already in 1941, under Vichy rule, the colonial administration in southern Dahomey had in an influential report made the point that ‘our means of persuasion is the appeal to interest; and the lure of gain is not attractive except when need makes it essential; coercion and fear are no longer à la mode’.Footnote 17 Consequently, we must consider whether locals interpreted the new methods from 1958 onwards to be compulsory. Furthermore, my discussion also connects to issues of ‘modernisation’ that most historians assume to be coterminous with the end of the late colonial state.Footnote 18 For Ghana and Nigeria, and more recently also for Côte d'Ivoire, the state of historical research on ‘development’ after independence has garnered increasing scholarly interest, but for Dahomey/Benin it is still in its infancy.Footnote 19 Much more work is also to be done on the French nationals who worked in Benin as part of the Coopération accords, known as coopérants.Footnote 20

The third level of potential analysis concerns local practices of and experiences with taxation. We know from some Beninese contexts that local populations had a long memory when it came to what they regarded as abusive taxation; therefore, it is essential to understand the view of the new, local officials on fiscal practices, but also, and especially, the perceptions and reactions of villagers.Footnote 21 Once again, the study of taxation — for Dahomey/Benin and much of West Africa — has remained focused on colonial experiences.Footnote 22 For Benin, taxation as problem rarely surfaces in scholarly works, except in interpretations of the end of the Kérékou regime (1990/91).Footnote 23 As an issue of practices of and debates on ‘grassroots neocolonialism’, local views of taxation after 1958 demonstrate the current gaps in research on the social history of taxation.

There are certain elements to Dahomey's trajectory from the late colonial period onwards that make it an especially interesting example. Under French colonialism, the principal European impression of urban Dahomey, especially of Cotonou, was that of a centre of intellectual activity (‘a Latin Quarter’ of Africa), but descriptions of its political and social experiences under late colonialism give a picture of stronger divisions than elsewhere.Footnote 24 Although Cotonou was an important port in the late 1950s, Dahomey's economy was based on palm products in the south and cotton in the north. In political terms, both colonial administrators and scholars of the early decades after independence upheld the image of an extraordinarily fragmented country, with three separate party movements for the poorer, more ‘tribal’ and chronically underrepresented north, the more ‘traditional’ Abomey region linked to the precolonial Dahomey Kingdom, and the urban regions of Porto-Novo and Cotonou. Political movements were also held to be ethno-regionalist.Footnote 25 But while this perspective has some value for explaining a specific type of political conflict in Dahomey/Benin between 1945 and 1972, it is very schematic. One could even challenge the alleged regionalist nature of some of Dahomey's movements: in particular, the UDD of Ahomadegbé, under the late colonial state, was in no way an ethno-regionalist movement. The goals of this party were, as is so often the case, a mixture of regional patronage politics and a representation of particular urban adherents.Footnote 26 They were, structurally, not so far removed from the better-known and more violent and effective strategies in Guinean nationalism discussed by Elizabeth Schmidt.Footnote 27

After independence in 1960, Dahomey experienced an early spate of military takeovers. Political instability seems to have triggered them; however, we can also read this ‘political instability’ as the resilience of (regionally-oriented) democratic structures.Footnote 28 In any case, in 1963, the military under Christophe Soglo intervened after a period of riots, ousting ‘northern’ prime minister, Hubert Maga.Footnote 29 The military leadership first installed a new civilian government under Ahomadegbé and, as president of the republic, his rival representing, in the ethno-regionalist view, the southern and more urban constituencies, Sourou-Migan Apithy. From 1965, Soglo removed the civilian leaders, but this only created a chain of rapid changes between phases of military and civilian rule until, in 1972, the Kérékou takeover marked the beginning of nineteen years of a sustained authoritarian regime.

The processes analysed here emerged against the background of such political change. They led to a number of comments and contestations, of protests and negotiations, at a moment when multi-party democracy was not yet dead, discordant voices were still accepted in trade union activity, and when agricultural reform policy and taxation were enlarged or reoriented after the experience of the late colonial state. In this article, I focus on two adjacent regions: the area around Porto Novo (which became the Ouémé province) and the administrative area of Abomey (which became the province — called département until 1974 — of Zou). Some additional evidence comes from other parts of southern Dahomey, especially from the region of Ouidah (which became the province of the Atlantique). This geographic framework offers a coherent regional set of sources for all three levels, given the importance of trade unionism, the role of oil palm agriculture, and an early focus of direct taxation in that area.

ACCESSING AND VALORIZING THE POSTCOLONIAL ADMINISTRATIVE ARCHIVE

The perspective taken in this article relies on the administrative archive (mostly formerly unknown archival holdings) — but it is used to write a social history at various levels, looking in particular at local experiences from the south of Benin. At first glance, for the uninformed observer, this might seem an unremarkable (or perhaps conservative) choice: after all, some recent studies have shown the potential of alternative written sources — such as NGO-produced material, local company archives or those belonging to religious institutions.Footnote 30 Interviews also offer important insights, especially as a commentary on a reinterpreted past.Footnote 31 In some cases, as Jean Allman has pointed out for the period of Nkrumah's rule in Ghana, the postcolonial documentation to be found in one country is largely insufficient to discuss a particular problem, and historians need to piece together from a number of archives.Footnote 32 Of course, such alternative sources and approaches are highly important. However, during this search for alternative access, historians wishing to work on post-independence social history disregard one (perhaps too obvious) type of source: postcolonial series of West African national archives and those of regional archives (which are therefore by no means conservative sources). Benin is no exception to this rule.

In part, this situation seems to be due to a deeply entrenched view about the unavailability of such material, which can lead to odd ideas and incongruous research situations. There appears to be a consensus that many of the potential archival sources cannot be accessed, that they may be stacked away or practically lost — in ministries, regional and local administrations, and so forth (or perhaps have even been destroyed, which is a standard argument). Such problems of access are obviously relevant. However, the fact that access to some of the archival data is difficult seems to blind researchers to the reality that the rest of these archival sources are indeed available, but are rarely or even never consulted, which makes of the whole issue a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. It is more than likely that the state of the many regional archives living through dramatic material decline would be more satisfactory if researchers showed an interest in their contents.Footnote 33 As a more practical observation, prestigious programmes for safeguarding archives, such as the British Library's Endangered Archives Programme, have on occasion attempted to deal with African regional archives, but not for postcolonial holdings.Footnote 34

Even in national archives, whole post-independence series remain virtually unknown and not utilized. Historians make surprising claims about the impossibility of writing post-independence histories on the basis of archives: a recent special issue in the influential journal History in Africa illustrates this point.Footnote 35 In at least some cases, the realities are quite different: rich archives do exist and are accessible, but working with them is challenging, due to a lack of inventories, the material conditions of the services that hold them, and possible difficulties of linking the information with useful field interviews and with existing interview material from the period itself. However, engagement with the archival material is overdue.Footnote 36 And, in a number of cases, only this engagement will provide the opportunity to preserve the archives themselves.Footnote 37 Thus the case that was recently made for Nigeria's Biafra state archives by Samuel Fury Childs Daly — ‘Those who study contemporary African history seldom have the luxury of working in a formal archive, state or otherwise’ — is certainly wrong when it comes to many other West African post-independence archives, although it is true that work in those archives is a hard task, and that the idea of ‘luxury’ rarely arises.Footnote 38

In my view, the lack of engagement with these new sources also has to do with the fundamental difficulty of writing post-independence histories of African societies, and with the massive lack thereof. More than fifty years after the historical period, historians still seem to be undecided as to how they want to address the history of African societies in the early post-independence years.Footnote 39 Recently, interest in the transition as a social history at all levels of the societies in question has rather receded. The political history of the transition process is still frequently studied as a kind of ‘late imperial history’, which normally ends with independence, and is challenged as an approach by historians of Africa.Footnote 40 Even recent studies in African history that combine political history with an intellectual history of political concepts in the late colonial period do not really pursue these questions into the period after independence.Footnote 41

In addition, paradoxically, historians also seem to struggle with regard to the ‘right themes’ to discuss. The social history of decolonisation remains a marginal issue, with the possible exception of the social impact of huge infrastructure projects, and the emergence of a new generation of experts. Even so, for West Africa, the principal studies of this type are focused on a very narrow range of countries, in particular on Ghana.Footnote 42 Discussions of the political mobilisation of a new African elite in the late colonial period tend to end with independence.Footnote 43 Socioeconomic problems, including the essential issue of taxation as a social practice and a practice of local rule, have also rarely been the subject of more profound analysis going beyond independence.Footnote 44 I therefore hope to contribute both to the opening of a more practical path for making use of existing archives, and to leading social historical analysis into the study of the first decade of the independent West African societies after 1960.

CONTINUITIES IN INSTITUTIONAL THINKING: CRITICIZING CONTINUITIES AT THE TOP LEVEL

Reflections of the political elite on continuity and change from late colonialism onwards were important in the aftermath of the events of 1963. The politicians, administrators, and trade union leaders who formed the new political elite after independence were now trying to draw conclusions from Dahomey's sociopolitical experiences after 1955. The activity of this elite was also informed by a more general sense of alarm. Social unrest and social conflict had been among the motors of regime change in 1963/64 in various African societies, with trade unions and youth movements taking a leading role during the ‘Trois Glorieuses’ riots that led to the fall of the Fulbert Youlou regime in Congo-Brazzaville in August 1963, and likewise played a role in the regime change in Togo and the attempted overthrow of the regime in Gabon.Footnote 45 In 1964, these events were not yet interpreted in Dahomey as part of a single wave of regime instability, but local elites became aware of the possibility of further violent falls of governments to come. At the same time, Dahomean union leaders had rather loudly formulated their aspirations for a substantial rise in wages in all sectors, and most notably public service. This activity was sufficiently aggressive that the most attentive observers of local policies, the French representatives, claimed that the demands and protests could lead to a new phase of destabilisation, this time hitting the new regime.Footnote 46

On 25 March 1964, Justin Ahomadegbé, already a veteran of late colonial and postcolonial Dahomey's political battles, now recently installed as president of the council after Christophe Soglo's military coup against the regime of Hubert Maga, had a long discussion with a delegation of leading trade unionists of the Confédération Générale des Travailleurs du Dahomey (CGTD). This was a critical moment of trade union activity, as the landscape of unions redefined itself after the end of Maga's regime, leading to new expectations and hopes, as Craig Phelan has rightly pointed out.Footnote 47 Ahomadegbé was well-placed to be an outstanding observer of these trends at the top level. In the late 1950s, during a practically unknown episode that triggered the first French security intervention in a decolonising territory aside from the very particular case of Cameroun — he had experienced, and personally experimented with, the power of workers’ mobilisation.Footnote 48 Notably, in April 1959, Ahomadegbé’s UDD joined the trade unions affiliated to the Union Générale des Travailleurs d'Afrique Noire (UGTAN) to protest against the electoral victory of the Parti Progressiste Dahoméen (PPD) in Dahomey. Although the activity was unsuccessful in the end, it showed the potential of such mobilisation in Dahomey's urban centres in the south.Footnote 49

The secret minutes of the March 1964 meeting are a key document in understanding views from the top level on continuities in Dahomean politics. While Saturnin Ahounou, Oscar Lalou, Jean-Pierre Agbahazou, and their CGTD colleagues hoped to get Ahomadegbé’s support against the existence of rival unions and against the government's plan for massive cuts in the public sector, the president complained about the continuities of thought that were, in his view, so characteristic of Dahomean trade unionism, but also of national and regional politics:

The President used a proverb in Fon, ‘yandégnigan’, and speaks about his politics of ‘cards on the table’; your outmoded formula, those Russian imperialisms, and French, and others; you should learn to guarantee that we leave these issues for good: numbers and words.

We do not have a public income of 7 billion [francs CFA] in Dahomey; Dahomey cannot produce more than 6 billion, but you, on the contrary, you spend 10 billion, to live more or less in a correct manner. Thus, we will have to find three billion!

Hence the situation. If you are conscious of the facts, you will not speak of 10 per cents, of minimum salaries, and of divisions. I offer you the language of truth, as a compatriot who is aware of the true state of the nation.Footnote 50

Ahomadegbé insisted, and this was intended as a criticism, that the trade union militants had completely failed to understand the ‘new times’. The rhetoric, the terminology, everything was wrong, the president of the council claimed. Those were remnants from the time when the ‘whites’ ruled:

It is you who called me and forced my gate. There is not even a need for a trade union, because there is no working class here; the trade union has its reason from the time of the whites who now lie in wait for you, and pour oil on the fire. Your histories of unions are ridiculous.Footnote 51

Thus, a principal observation — or accusation — from the president of the council's part was that a high proportion of the country's elites failed to understand that colonial rule was actually over. They were just continuing, in their political language as well as in their principal demands and expectations, a ‘late colonial style’. This was unhelpful for any conceivable kind of political and social modernisation:

You talk as if you were speaking to Bonfils [a principal French governor of the 1950s]! But this is an Ahomadegbé, descendent of Tomêtin, thus an authentic Dahomean!Footnote 52

This observation was all the more remarkable as members of Dahomey's southern urban elite, including those who were more closely linked to networks around the French embassy, had a tendency to regard Ahomadegbé as an old-style politician of the colonial period, as someone who resembled much more strongly a paramount chief than someone used to democratic electoral systems.Footnote 53 At best, those observers commented, one could say that Ahomadegbé was ‘more comfortable at village celebrations than at the cocktail parties of an All-Paris style’.Footnote 54 Even so, what is more important for my discussion is that the president of the council demanded restraint and a break with late colonial customs regarding the use of public budgets. Indeed, from independence to 1964 the crisis of those budgets had massively worsened. This disaster seemed to have gone unnoticed by many interest groups in Dahomean society. Continuities in spending from the late colonial period constituted a significant problem. French reluctance to pay subsidies after the 1963 coup d’état and the imprisonment of Maga aggravated this crisis; Ahomadegbé calculated with budget cuts of 25 per cent. The trade unions leaders were invited to behave accordingly.Footnote 55

The attack against continuities in thinking, so dramatically pronounced by Ahomadegbé, impressed the trade union delegates. It was difficult for the union personnel to argue against the accusation of the continuation of a colonial mindset.Footnote 56 But this pattern of continuities, as denounced by an impressive survivor of the turbulent first years of postcolonial Dahomean politics, need not necessarily be sought only at the top level and in terms of labour institutions or political leadership. Beyond the few larger industries and the public sector, notions of continuity of perceptions and behaviour also existed in the rural context.

REGIONAL-LEVEL DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS: CONTINUITIES AND MEMORIES OF LOCAL POPULATIONS AS AN OBSTACLE

By 1962, a year before the dénouement of the Maga government through Christophe Soglo's coup d’état, various Dahomean leaders had shared their frustrations with the French high representative in Cotonou. The principal notion was that one could not trust local populations regarding their work ethic. Dahomean politicians commented that ‘their citizens had hastily admitted that Independence meant the end of any kind of constraint and that, notably, the need to work was to disappear with the colonial regime. The candidates had not refrained from campaigning on that theme at the 1960 elections.’ Now, however, the political elite of the unity party, the PDU, proclaimed once again the importance of work; ‘work’ even became a mythical watchword, and the object of a four-year plan.Footnote 57

These debates followed a frantic discussion on the future of agriculture and attempts at implementing alleged agricultural innovation, which had dominated the south of Dahomey in particular in the 1950s. During the years of transition between 1957 and 1965, ‘modernisation’ projects at all levels were at an all-time high. Agricultural processes were to be changed and eventually mechanized, focusing both on the former colony's classic production specialty of palm products and on the expansion of food agriculture, such as for rice. Agrarian reform was initially left in the hands of the remaining French officials, who, as ‘experts’ with longstanding experience on the ground, were regarded as the principal agents of change. However, after 1958 this sector, like other parts of the administration, was about to be ‘africanized’, with the introduction of a number of new, Dahomean, mid-level agents.Footnote 58

The Porto-Novo region is an illustrative example for the ‘difficulties’ created by local populations believing that the more recent practices of agricultural organisation represented continuity with older experiences under colonial rule, and in particular with its repressive routines. A. Colombani, district commissioner (commandant de cercle) of the Porto-Novo district at the end of the colonial period, was the first to be used as an agricultural reform expert. Colombani was aware very early on, by late 1958, of the financial difficulties that many of the districts would face in the near future.Footnote 59 He recommended reliance on an important concept of late colonial agricultural policy: the creation of rural cooperatives, seen as the main lever for encouraging ‘uncivilized’ peasants to produce in more rational ways, to their own and the territory's benefit.Footnote 60 Under the conditions of an autonomous Dahomean government, Colombani's tone did not necessarily reproduce the negative, racist mainstream thought that still dominated the discourse of the late colonial period; rather, the official gave a paternalistic description of the peasants of the Porto-Novo district as intelligent and strategic. The main problem the administrator identified was that local agriculturalists felt no need to expand their range of production.Footnote 61 Nothing would advance in that direction if the peasants in question were not forced into cooperatives they did not wish to have.Footnote 62 Thus, the logic of coercion, so characteristic of colonial structures and processes, was once again presented as a necessary measure.

Indeed, local peasants were easily antagonized by what they regarded as the coercive elements of these experiences. In 1959 and 1960, Pierre Gbénou had the task of travelling through the district of Porto-Novo to persuade local peasants to ultimately accept their integration into local cooperatives. His reports and correspondence are an important source to qualify Colombani's interpretations. Indeed, they point to a number of perceived continuities that are at the heart of the problems. Gbénou's experiences — which need to be read as comments by a Dahomean official who wished to show his worth, but who held a genuine concern for the worries of the rural populations — make it clear that the resistance of local agriculturalists to cooperatives and new products was not simply fear of the unknown. In March 1959, some rural populations such as in Yokon and Zonguè in Adjohoun subdivision, and in Sado in Banlieue subdivision, responded positively in principle both to the cooperatives project and to propositions regarding new plants.Footnote 63 However, many others were fundamentally hostile. As in the case of Gbada (in Adjohoun subdivision), local peasants informed the official that they saw in the cooperatives a clear element of forced labour. The rejection of collective agriculture in large parts of the Porto-Novo district was thus justified by dramatic historical experiences of coerced labour and violence connected thereto — and little could be done in these cases in the following years to make the idea of the cooperatives work.Footnote 64

For the Abomey district, these tensions are more difficult to find but were equally present. Local political representatives warned against possible resistance by the end of the colonial period, and it was once again Justin Ahomadegbé, then a territorial councillor of that district, who pointed to the sense of continuities, although this time on the part of frightened peasants. In the Abomey region, Ahomadegbé claimed, the local memory of collective labour as coerced labour was too strong. Any reliance on agricultural cooperatives in the classic, late colonial tradition would therefore be unacceptable to these rural populations.Footnote 65 The only way to change the dynamics of the situation was, according to Ahomadegbé, to link the idea of cooperatives to older, and ultimately precolonial, forms of rural cooperation. He specifically discussed the image of the donkpè societies.Footnote 66 Only such a positive connection would make the cooperatives initiative palatable.Footnote 67 Recourse to the traumatic past with regard to peasants’ experiences and their resistance to collective fields was also made in the arguments used against important figures of the Soglo regime in 1967. Such was the case of General Philippe Aho, subsequently put on trial for the illegal confiscation of villagers’ fields.Footnote 68

The continuity hypothesis and the criticism linked to it was thus not only formulated by top-level politicians and directed against officials from trade unions and similar institutions formed in the late colonial period. Local peasants in southern Dahomey also feared the possible dangerous heritage of colonial coercion; by 1962, reports from the Abomey region demonstrated that the resistance to collective fields had not waned at all. Local officials tried to admonish the rural populations that this was no longer the ‘time of the French’, in which resistance was ultimately justifiable, but a new period in which the villagers had to take part in the effort. However, it was perhaps not the best strategy to proclaim that ‘[t]he recalcitrant individuals, the obstructers […] will be arrested and sent and sent [sic] to the North to work on fields reserved for the bad citizens’ — a comment that, once again, was reminiscent of colonial forced labour!Footnote 69 On the subject of taxation and its failure at the local level, this connection was likely even stronger.

FAILURES TO IMPROVE THE TAX BASE LOCALLY: THE CONTINUITIES OF LOCAL RESISTANCE AND DESPAIRING AUTHORITIES

Resistance — in the broadest sense of the word — to taxation had a long tradition in southern Dahomey. In the 1920s and 1930s, episodes of tax resistance led to repression and the imprisonment of local leaders.Footnote 70 Shortly before the Second World War, tax levels remained notorious in the Porto-Novo district — they were regretted by colonial officials, and provoked resistance.Footnote 71

Insufficient budgets had been the principal cause of risky tax politics — risky because they led to discontent and local reactions — but in the 1950s modifications caused further problems and mobilized dangerous memories. In 1958, the council of dignitaries of the Abomey district exempted women from the district tax, thus halving the available resources for road maintenance. The council advocated for the introduction of communal labour, making the rural communities liable for organizing road maintenance locally. First experiments with such a policy, with diverse results, also showed that villagers acknowledged these practices as a new form of classic colonial forced labour, in which the roads had been the principal field of coercion.Footnote 72 ‘There we have it, the really big problem’, the administrator of the subdivision held, while Ahomadegbé, as territorial councillor, warned against the connection to forced labour.Footnote 73

With late colonial strategies shifting costs and responsibility for welfare to African regional leaders, French credits and support programmes in Dahomey dried up after the granting of semi-autonomy in 1957.Footnote 74 Under the autonomous government of Hubert Maga budgets were already highly unstable, and at the end of colonial rule in 1959, the Maga government voted in favour of the first austerity package, leading to a massive increase in direct taxes.Footnote 75 However, by 1962, the French observers of the High Representation (Fr. Haute-Représentation, later Ambassade) — stereotyping Dahomean society but accurate in intuiting the difficulties of the Maga regime — decided that the Dahomean state's tax basis was entirely insufficient. The government would need harsher tax measures, including the taxation of female household members, which was regarded as an extremely unpopular measure.Footnote 76 In this context, local authorities attempted to downplay the effects, and taxpayers demonstrated against the measures.

In the Abomey district, the transition of taxation from the French administration to a new generation of Dahomean fiscal employees and village chiefs was very difficult. From the start, there was proof of tax officials benefiting their families and partners.Footnote 77 In other cases — since the region of Abomey was a UDD stronghold — local tax collection was used to co-finance the dominant party, as investigators found.Footnote 78 However, individual enrichment combined with patronage in the local context was another phenomenon, and difficult to distinguish from the first.

In the village of Hounto, in May 1959, the village chief warned against local resistance over the methods of registration. Villagers were angry about the repeated failure to remove the deceased, invalids, and emigrants from the lists of taxpayers, whose contributions had to be paid for by their families. Residents went into hiding during the tax exercise, and this directly hit the rural region, where financial means were too scarce to improve the system of wells.Footnote 79 The regional administrators complained that the system of registration, without nominal local tax register, allowed village dignitaries and local alliances to commit all kinds of abuses.Footnote 80 In various cases, taxpayers’ contributions disappeared into the pockets of local chiefs. In November 1958, the administrator of the central subdivision of Abomey, Maurice Pernon, received a letter of complaint from Camille Behanzin, paramount chief of Allahé, and dignitaries from the village of Attogouin about the local chief who was accused of having stolen the money of the villagers.Footnote 81 His son, acting chief in 1959, confessed to having used this money for ‘fetish rituals’; he was arrested and imprisoned, but the administration commented that this was a more general problem.Footnote 82 The district authorities complained that the only dignitaries imprisoned were ‘old men’, who had themselves paid their taxes and were now held responsible for crimes they had not committed, whereas wider sanctions were complicated to implement. By the end of 1959, tax collection remained nowhere near the targeted 80 per cent of imposable sums.Footnote 83 A number of local chiefs who remained in this transition period the principal partners of the tax administration failed to demonstrate much engagement with that role, even though the chiefs of the ‘traditional districts’ (or cantons) received a portion of the collected sum as an incentive. It would seem that the fear of local political unrest was great enough to stifle the motivation of the local dignitaries. Tindji, for example, was a hotbed of such local uproar.Footnote 84

The troubles around taxes did not disappear. On the contrary, the vote on new taxes in 1960, the so-called departmental taxes, led to an ever stronger wave of tax refusal within and beyond the Abomey region. Local deputies were unwilling to support unpopular measures publicly, and this situation was in Abomey's case exacerbated by the UDD's role in the opposition (and as a clandestine movement some months later) from its break with the Maga government onwards, although local perspectives prevailed in the matter. Exasperated, the prefect of the region called on the politicians to change ‘absurd’ local attitudes.Footnote 85 But the politicians in question did not give such support. The imprisonment of Justin Ahomadegbé between May 1961 and November 1962 aggravated the political situation in the former UDD stronghold that was the Abomey region.Footnote 86

In January 1962, more than half of the inhabitants of the village of Avlamé refused to pay their taxes, with the members of the banned UDD led by Sikatanon Agbahon at the forefront; protestors in the region regarded the fact that the provincial authorities only dared put this leader under arrest for a single night to be a victory.Footnote 87 At the same time, however, the local vice-president of the unity party, PDU, one Azongnidjè, forced the village chief, Gbogbanou Aouèdo, to hand over 75 per cent of the taxes obtained in the name of the regional deputy in parliament. The vice-president was later accused of having kept the money for himself.Footnote 88 In Zêko, in the canton of Tindji, a number of locals similarly refused to pay their taxes, and organized tax resistance on the public works site of Dan-Lallo.Footnote 89 Some other village chiefs sent lists of tax resisters to the regional authorities, which often intermixed local conflicts and observations on tax refusals.Footnote 90

The report by an Itinerant Commission of Civic Propaganda, a body of parliamentary deputies of the Abomey Region specifically created to understand the problems of tax collection, contains important comments on the situation. In their speeches in the region, the members of the commission insisted on the restoration of unity, and on higher taxes with a view to creating local infrastructure and welfare.Footnote 91 Commission members regarded the colonial past as a powerful tool for encouraging local populations to take part in the public effort:

The whites are no longer in command. They have left for their country. We are independent, and we, the Africans, we rule over ourselves. At our head, we have placed President Maga who holds all the powers. The schools, the hospitals, the maternités [maternity clinics], the postal services etc. all these services continue to function, to work regularly like in the times of the whites. You know that they, when they left, took their money with them. You should also know that the Whites, the French, are hard workers …. They have become very rich. It is with that money that they keep their country up, a country that has become so beautiful. They had surplus money which they spent on our country at the time when they ruled over us.Footnote 92

But the commission also used colonial memories of violence to intimidate the locals into paying the taxes. They conjured the image of the ‘native guards’, the principal task force of the colonial administration during tax collection, brutalizing the villagers. This was linked to the idea of male villagers losing their dignity in the eyes of their wives in such moments of corporal punishment, saying that ‘[y]our wives will no longer respect you if you get beaten by the guards before paying your civic taxes’.Footnote 93 Commission members claimed that local populations were afterwards responding enthusiastically to the tax exercise and that evoking the option of violence had been quite effective. Both claims were overly optimistic.Footnote 94 Even after the downfall of the Maga regime, in December 1963, the Controller of Taxes at Bohicon complained about widespread fraud and evasion.Footnote 95 And under the rule of Christophe Soglo, the difficult financial situation of regions such as Abomey led to the introduction of new taxes once again, for example on oil pumps and use of public domains, which only added to the recalcitrance of local populations.Footnote 96

The resistance to local tax obligations remained vigorous long after the end of post-independence party politics and the installation of authoritarian rule in Dahomey. One documented case is that of the villages of Savi Houéton and Dékouènou in the urban district of Ouidah: in 1975, inhabitants of both villages threatened the tax collectors with hatchets and made them withdraw. The Council of the Revolution (CCR) made it clear that this was by no means an isolated case: ‘We have to note that the population of our urban district tends to think that Revolution means disorder and anarchy’, council members claimed with regard to the tax problem.Footnote 97 Accusations of local politicians pocketing a portion of the collected taxes, such as in the case of Adjahoumê, also remained a common phenomenon.Footnote 98 Thus tax evasion continued along paths reminiscent of the colonial situation. Yet by 1972, the comparison with colonial conditions no longer featured in the local and national rhetoric on the issue.

CONCLUSION

With Dahomean independence leading to a complicated democratic system and the first experience of more sustained repression by 1961, reference to the colonial past was made on frequent occasions, and at different levels of interpretation. Political leaders invoked the colonial past to admonish trade union officials about their ‘outmoded’ view of politics; peasants saw it as a dangerous heritage and feared a return to coercive models of forced agriculture; local politicians and officials used it as a warning in calling for more ‘traditional’ forms of collective work; in speeches by members of the new political elite, it was employed to justify worsening economic and tax conditions; and it revealed a past of successful evasion measures to villagers who refused to pay their contributions to the regional administration.

The argument was very powerful. Trade union leaders who negotiated with Justin Ahomadegbé, rehabilitated and again in a prominent position in the country, could not simply brush away the accusation of behaving ‘like in colonial times’. It was quite clear for them whose interests they normally had to defend — the wage workers, especially those in the public sector, whose salaries were threatened by a 10 per cent cut and worse measures to come — but the claim made by the president of the council, that they were not adapting to postcolonial times but rather maintaining the style of colonial trade unions, was a brilliant means of silencing them. The unions only found their old vigour again in the late phase of the Soglo regime, in 1967, under different conditions.

Mentioning colonial politics and their continuity in the first years after independence was also a mighty argument in the context of rural life. Politicians and administrators of the nationalist generation of the 1950s were afraid of being accused of sympathizing with coercive labour methods, as colonial forced labour had been, until 1946, a principal point of local scorn and mobilisation. This made rural policies such as of cooperatives difficult, as those effectively prolonged late colonial models. They could be linked to remembrance of colonial policies of expropriation and land confiscation — which was a worrying problem.

With regard to taxation, the issue was yet more complicated, as the postcolonial administrations needed taxes, and even more taxes than the colonizers had demanded from Dahomean populations after the Second World War. Unlike with collective land schemes, which could be cast in a precolonial light with reference to the donkpè societies, the only choice here for the administration was to find a positive argument for the colonial model, and to point to the importance of tax for infrastructure, in a logic that went back to the late colonial period.

The degree of arguing with recourse to the past needs to be neatly separated from the level of perceptions of that colonial past. Thus, for trade union officials, the 1950s had certainly been a kind of golden age in social terms, a period when their work was most respected (in spite of all the clashes with the late colonial administration) and the function of the union was unchallenged. Rural populations, on the other hand, knew very well what they had lived through in terms of coercion under the collective agriculture schemes of colonial rule, and were ready and able to mobilize resistance against any renaissance of such policies. The opposite was true concerning taxation, for which the colonial years of successful tax evasion hinted at future possibilities of tax resistance: those who had been able to defend themselves against the violence of the colonial ‘native guards’, certainly stood a chance of coping with the Dahomean local police, whose status was held to be much weaker.

Studying this continuity is compelling, the individual cases also tell us a lot as far as the potential of the formerly unknown, regional, and national post-independence archives are concerned. It is clear that for Dahomey/Benin — as for Ghana and other West African countries, where equally rich and equally untapped postcolonial archives exist — the interpretation of such archival holdings leads us to particular regions and issues of conflict. For other regions for which archival evidence is more difficult to find, a more profound discussion is still possible on the basis of further field interviews — that is, where the memories of local informants have not been supplanted and distorted (like in the case of Benin) by the ‘instability’ of the first twelve years after independence, the very particular type of repressive rule after 1972, and the turbulence of democratic transition and ambiguous experiences with democratic rule after 1989.