Introduction

The majority of evidence-based treatments do not become adopted in routine clinical care [Reference Greenhalgh and Papoutsi1,Reference Greenhalgh, Robert and Macfarlane2], and when they do, they take much too long to become integrated into routine clinical practice. In fact, research has suggested that it takes 17 years to turn only about 14 percent of original research into routine patient care [Reference Morris, Wooding and Grant3,Reference Chalmers and Glasziou4], and the majority of implementation failures are often rooted in context [Reference Rafferty, Jimmieson and Armenakis5,Reference Balas and Boren6]. Key reasons for why clinical trial outcomes fail to translate into practice include lack of relevance to patient quality of life and treatment preferences, provider lack of time, tools, or training, cost of implementation, lack of a purveyor, and healthcare organizational barriers such as lack of incentives, processes, or technologies to facilitate treatment use by frontline providers over time [Reference Heneghan, Goldacre and Mahtani7]. Such factors often are not accounted for in the design of clinical trials. Adoption of research results into clinical practice and guidelines is a vital component for a learning healthcare system, including the VA.

Implementation science, “the study of methods to promote the adoption and integration of evidence-based practices, interventions, and policies into routine healthcare and public health settings to improve the impact on population health” [Reference Kilbourne, Elwy and Sales8], can help solve this gap. Implementation science utilizes strategies that facilitate provider adoption of interventions that are proven effective in the post-trial period, especially when faced with resource constraints. Implementation strategies are highly specified, theory-based tools, or methods used by organizations or providers to facilitate adoption of an effective treatment.

Despite the value of implementation science, most clinical trials in the United States are not designed to take implementation planning into account. Likewise, to date VA’s clinical trial evaluation approach has not included translational steps to support comprehensive implementation planning and assessment of effective treatments once the trial is completed. Without a specified process for existing providers and sites to ensure trial results are adopted in routine practice by multi-level interested parties once the study is completed, scale up and spread is very difficult. Implementation planning assessments (IPAs) address this lack of uptake by utilizing real-world data to understand the uptake, use, and effectiveness of the intervention, thereby ensuring that evidence-based interventions are set up for successful implementation in clinical practice.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), with its long history and tradition of comparative effectiveness and process-driven thinking, offers an ideal opportunity to develop and deploy an implementation plan. For over 90 years, the VHA Office of Research and Development (ORD) has supported groundbreaking multisite clinical trials, most notably through CSP [9]. Historically, CSP has developed and deployed multisite clinical trials within VHA and the nation by using a model that involves multi-disciplinary teams of VHA investigators and national program office leaders to support buy-in and application of trial results within VHA. CSP has also used a standardized robust process evaluation [10] to ensure fidelity to trial protocol, design, and internal validity which includes commonly used quality assurance processes and also meeting registration requirements under the International Organization for Standardization 9001 criteria.

In 2019, VHA ORD instituted a requirement that all CSP clinical trials include an Implementation Plan as a condition of funding to ensure trial results are adopted in clinical practice in VHA and beyond. This requirement stemmed from the Chief Research and Development Officer’s strategic priority to increase the substantial real-world impact of research and to support the use of the ORD VA Research Lifecycle Framework [Reference Kilbourne, Braganza and Bowersox11]. This Framework maps how clinical trials can incorporate planning and data collection to ensure interventions, if proven effective, are ready to be used by frontline providers in routine care settings. Accordingly, CSP adopted requirements that all new trials include an Implementation Plan, which outlined a process for preparing treatment interventions for their implementation in the aftermath of an effective trial. The Implementation Plan prompts more in-depth data collection on usability and acceptance of the intervention during the trial, while also planning for sustainment by identifying opportunities to embed the effective treatment into routine care, programs, policies, or through marketing.

VHA studies that have not had an implementation plan have struggled to use trial results to impact real-world clinical practice. For example, a VA CSP study published in 2018 showed superior efficacy of a rigorous model of supported employment, called Individual Placement and Support (IPS), for unemployed Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD compared to usual vocational rehabilitation services [Reference Davis, Kyriakides and Suris12]; however, VHA has yet to broadly disseminate IPS services to the vast PTSD population beyond a handful of medical centers. In retrospect, proactive implementation science tools may have accelerated the pace of real-world service delivery of the most efficacious treatment.

Current national efforts to move trial results to implementation have been hampered by a lack of a detailed process for embedding implementation science methods into clinical trials. Current research, notably from the experience of the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs), outlines a foundation that describes the need for national standards of embedding implementation science into clinical research [Reference Leppin, Mahoney and Stevens13,Reference Kilbourne, Jones and Atkins14]. To address the gap between VA CSP trials and recent implementation plan requirements, we developed the CSP IPA Tool, which has become the basis of CSP Implementation Plans.

The objective of this manuscript is to present the new IPA Tool (Table 1), which provides step-by-step guidance that can be used by trialists in healthcare settings to facilitate future implementation and translation to clinical practice of trial results that support the effectiveness/efficacy of the tested treatment or intervention. To further showcase the practical application of the IPA Tool, we provide a real-world case example from a CSP clinical trial to illustrate the types of data and steps required to complete an IPA (Table 2). Findings from use of our IPA Tool will inform how the trial intervention, if proven effective, can be further deployed across the VA system and beyond to reduce the gap between research and real-world practice. Altogether, these activities are to serve as foundational elements for a broader enterprise-wise strategy for VA-funded studies.

Table 1. The Implementation Planning Assessment Tool 1

1 While the tool was designed for use in both efficacy and effectiveness trials, effectiveness trials will have broader and more involved implementation methodology since they focus on answering the question: do the intervention benefits hold true in real-world clinical settings? In contrast, the tool will be more limited in efficacy trials since they focus on the answering the question: does the intervention work in a highly controlled standardized setting? Therefore, throughout the tool, we have indicated sections that may not be useful during efficacy trials.

2 See Frayne SM, Pomernacki A, Schnurr PP. Women’s Enhanced Recruitment Process (WERP): Experience with Enhanced Recruitment of Women Veterans to a CSP Trial. Invited national VA HSR&D CyberSeminar, presented November 15, 2018. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3565

3 Denotes overlap between Planning, Framing, and Aligning Interested Parties Phase and Implementation Process Data Collection phases.

Table 2. Case study example using the Implementation Planning Assessment Tool 1

1 While the tool was designed for use in both efficacy and effectiveness trials, effectiveness trials will have broader and more involved implementation methodology since they focus on answering the question: do the intervention benefits hold true in real-world clinical settings? In contrast, the tool will be more limited in efficacy trials since they focus on the answering the question: does the intervention work in a highly controlled standardized setting? Therefore, throughout the tool, we have indicated sections that may not be useful during efficacy trials.

2 See Frayne SM, Pomernacki A, Schnurr PP. Women’s Enhanced Recruitment Process (WERP): Experience with Enhanced Recruitment of Women Veterans to a CSP Trial. Invited national VA HSR&D CyberSeminar, presented November 15, 2018. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3565

3 Denotes overlap between Planning, Framing, and Aligning Interested Parties Phase and Implementation Process Data Collection phases.

Materials and Methods

Implementation Guidance and Planning Assessment Tool for Clinical Trialists

The IPA Tool was developed by authors CPK, LMK, and ALN and is informed based on principles outlined in the Implementation Roadmap developed by the ORD Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) as well as main components and principles of the field of implementation science [Reference Greenhalgh, Robert and Macfarlane2,Reference Bauer, Damschroder and Hagedorn15-Reference Hamilton and Finley17]. The IPA Tool was developed through a systematic process by an interdisciplinary team with expertise in implementation science, clinical trials, program evaluation, and qualitative methods; team meetings with an organized set of agendas over a period of time were used to develop and refine the tool.

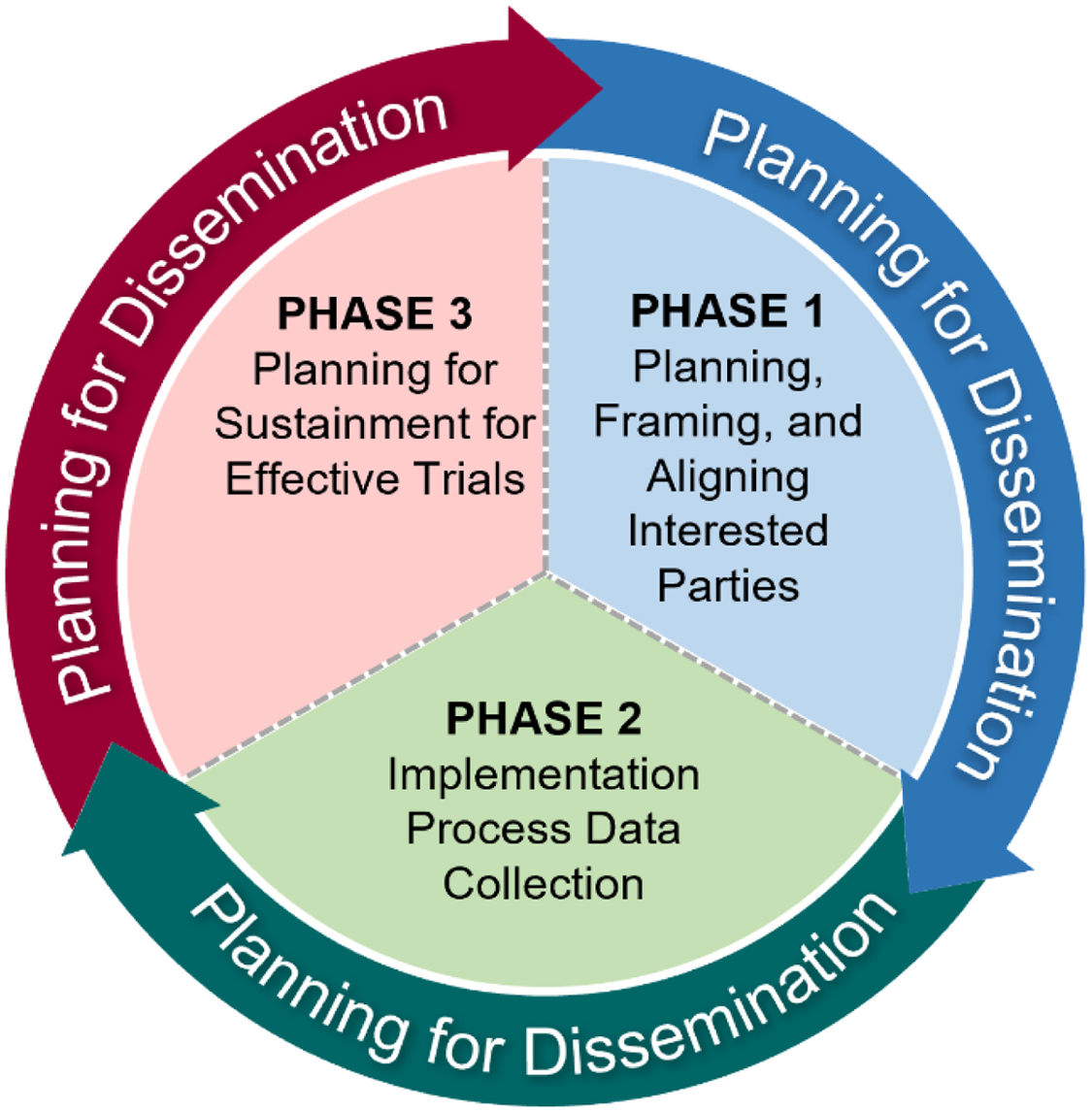

The IPA Tool emphasizes three phases that are adapted from the QUERI Implementation Roadmap [Reference Kilbourne, Goodrich and Miake-Lye18] of incorporating implementation science to accelerate the adoption of interventions into routine care (Fig. 1). The first phase, “Planning, Framing, and Aligning Interested Parties,” involves identification and garnering of input from multi-level (e.g., local, regional, and national level) interested parties who have a vested interest in the trial’s results and potentially the leverage to incorporate results or effective treatments into routine practice via organizational changes. Importantly, interested parties should include Veterans or patients to provide input on treatment use from an end-user perspective. In clinical trials, interested parties could include, but are not limited to, frontline staff, clinicians, nurses, leadership at different levels including national, regional, and local, clerks, check-in staff, Veterans or other patients, caregivers, operational leaders, and policymakers. See Table 3 for a broad spectrum of potential partners who may have a direct or indirect role in supporting the design, delivery, or receipt of the intervention. The second phase, “Implementation Process Data Collection,” involves planning and assessment by clinical and research leaders that will promote uptake of the intervention if found effective and the enactment of an IPA Tool. The third phase, “Planning for Sustainment for Effective Trials,” takes results from phases 1 and 2 to outline a process by which trial results and interventions (if proven effective) will be adopted in routine practice. Throughout all three phases, the assessment team should also be “Planning for Dissemination,” which involves sharing information about the intervention, implementation, and trial results to increase uptake among key interested parties.

Fig. 1. Framing for the Implementation Planning Assessment Tool.

Table 3. Interested parties

After the tool was developed, authors LD and TK applied the tool retrospectively, reflecting on a recently completed CSP clinical trial that was selected based on some characteristics for which the tool is intended to apply and highlighting concrete impacts of missed opportunities that could have been addressed had the tool been used throughout the life of the trial (Table 2).

Results

Implementation Planning Assessment Tool

This tool was designed to help trialists systematically think through essential components of an implementation science-informed process plan that is flexible enough to address the wide spectrum of research questions evaluated by clinical efficacy and effectiveness trials. While the tool was designed for use in both efficacy and effectiveness trials, effectiveness trials will have broader and more involved implementation methodology since they focus on answering the question: do the intervention benefits hold true in real-world clinical settings? In contrast, the tool will be more limited in efficacy trials since they focus on the answering the question: does the intervention work in a highly controlled standardized setting? Therefore, throughout the tool, we have indicated sections that may not be useful during efficacy trials. Trial proponents are encouraged to consider this tool as a prompt (i.e., at the time of study design/planning) to consider key issues to help promote consistency and rigor across the implementation plans developed for different trials. The tool will enable a way to capture real-world data to understand the intervention’s use and effectiveness over time as well as generate a comprehensive plan for ensuring trial results will be utilized by frontline providers in routine care settings upon study conclusion.

The intention is for this tool to be completed as an iterative process and the teams and individuals can and should refer to the tool at different points in time throughout the trial. For example, planning from phase 1 will impact later work in phase 2 when the team will speak with different key interested parties, possibly during team or advisory planning meetings. Then those areas of the table within phase 2 can be completed as the team moves forward with the trial.

Phase 1: Planning, framing, and aligning interested parties

In a non-clinical trial setting, the first phase would be referred to as “pre-implementation work.” However, within the clinical trial setting, we have labeled Phase 1 as “Planning, Framing, and Aligning Interested Parties” because using the term “implementation” would be a misnomer, since in the context of a clinical trial, effectiveness has not yet been determined and equipoise must be protected during the course of the trial. Phase 1 assesses the many complex factors that influence implementation or uptake of new programs, in addition to their success or failure. Formative evaluation (FE), defined as a rigorous assessment process designed to identify potential and actual influences on the progress and effectiveness of implementation efforts, is an essential means to systematically approach this complexity [Reference Stetler, Legro and Wallace19]. FE systematically examines key features of the local setting, detects and monitors unanticipated events, and adjusts, if necessary, in real-time, and optimizes implementation to improve potential for success [Reference Hulscher, Laurant and Grol20]. This understanding is essential for efforts to sustain, scale up, and disseminate any new EBI. Otherwise, there is potential for failure to account for specific contextual issues in program implementation.

Phase 1 includes the first steps of FE in the IPA Tool beginning with asking what is the challenge or issue that the treatment or intervention is trying to solve, and what are the core elements that are hypothesized to achieve its desired effect on health? This needs to be explicitly mapped out and the interested parties involved in the intervention need to be identified. Staff time and resources should be protected to support Phase 1-3 work, for hereafter these staff will be referred to as “assessment planning staff.” While CSP has expertise in identifying national interested parties, such as national clinical program office leads, the Implementation Lead or other staff helping to complete the assessment will assist with identifying local interested parties including patient, clinical and non-clinical staff, and policymakers. Frontline users (clinical and non-clinical staff) should provide input into the deployment of the treatment or intervention. Veterans (or other patient populations as appropriate) should be asked to provide feedback on equity, barriers, and satisfaction. Organizational leaders who will decide about eventual program adoption should also be included in planning efforts to understand their concerns and priorities. Assessment planning staff will also help inform, as appropriate for the trial design, the design of the intervention to be implemented (design-for implementation, user-centered design) and deployment of the intervention. Contextual factors, such as competing demands, belief or lack of belief in evidence, loyalty to usual care modalities, available resources, leadership support level, clinical and/or operational policy, and frontline buy-in, will be assessed and documented. Barriers and facilitators to implementing the intervention will be assessed through mainly qualitative data including interviews, focus groups, conversations, and advisory call or meeting notes. Preliminary plans for the intervention’s sustainment (once the trial ends, if found effective) should begin. The plan should take into consideration any administrative or policy changes needed at the national and regional levels. These can include, but are not limited to, formularies, labs, electronic health record fields, national directives, or other services policies, budgeting, the time, tools, and training required by clinicians at the frontline to deliver the intervention, location for new service delivery (e.g., primary care, specialty care clinics, Community-Based Outpatient Clinics), and Veteran level of interest, time, and burden required to participate in the evidence-based intervention (e.g., visits, required lab tests, medications).

Phase 2: Implementation process data collection

Phase 2 involves the ascertainment of factors affecting the use of the CSP intervention at the routine practice level, notably through information on provider and patient acceptance, implementation and intervention costs and organizational factors, and fidelity to the implementation of the intervention or treatment, where relevant. Within clinical trials, the intervention is typically implemented within a controlled research context. Even when pragmatic trial design principles are included, there still remains some elements that do not perfectly mirror a clinical practice context. While a clinical trial may hire staff to deliver the treatment or intervention, the data collected for a clinical trial will likely be different than data collected from routine clinical providers. Both perspectives will be essential and data collection should incorporate both.

Critically important will be the continuation and protected time of the implementation assessment team, including involved staff. Implementation plans initiated during Phase 1 will now be finalized. The key barriers and facilitators identified during Phase 1 will be used to select and define implementation strategies. The implementation strategy dose [Reference Proctor, Powell and McMillen21] along with the implementation outcome most likely to be affected by each strategy should be documented. Likewise, justification should be provided for the choice of implementation strategies, including theoretical, empirical, or pragmatic justifications. Adaptations or resources will be deployed that are necessary to fit for local contexts. This will include planning proactively how the intervention may need to be adapted going forward to better fit real-world contexts (i.e., What adaptations are needed to be able to implement the intervention?), the identification of strategies to support the people and clinical interested parties delivering the intervention to Veterans [Reference Johnson, Ecker and Fletcher22] (i.e., Which implementation strategies will help overcome barriers and improve implementation of the intervention?), and determination and planning for evaluation of the benchmarks of successful implementation should take place.

Phase 2 will use a combination of both qualitative and quantitative data collection, known as mixed methods data collection [Reference Creswell JWaC23], to formatively identify and evaluate how multi-level contextual factors at the Veteran-, patient-, clinician-, facility-, or health system-level serve as barriers or facilitators to quality delivery and receipt of the trial intervention over time. Secondarily, some formative process data can be shared in trial staff meetings to make iterative improvements to key protocol steps as a quality assurance step to address unanticipated research challenges, such as achieving participant recruitment and enrollment goals or fostering adherence to clinical lab monitoring.

Phase 3: Planning for sustainment for effective trials

Upon trial completion, the IPA team can use data collected by mixed methods approaches to help make a summative judgment regarding the influence of context on study outcomes. This is crucial to determine how the trial results will be used in routine care once the study has ended, while also developing a plan to implement interventions if proven effective. Key lessons from this formative and summative process evaluation can be used in the future to help clinicians and healthcare sites deliver the intervention protocol more effectively, thereby accelerating the uptake of interventions found to be effective following validation of clinical impact.

If the intervention is found to be effective, it is important for there to be sustainment planning activities in place so that continuity of patient care through the intervention is maintained. Sustainment planning will help evaluators and researchers understand how the intervention will be used in routine care once the study has ended. Accordingly, results from Phase 1 and 2 will inform clinicians and healthcare sites in understanding how to deliver the intervention protocol more effectively, make appropriate adaptations, and sustain the intervention over time. The implementation team should identify how sustainment and further dissemination (e.g., scale-up and spread in sites beyond the original study sites) can be tracked over time through tools such as surveys or dashboards. If Phase 1 and 2 data have shown that certain implementation strategies will be more effective at sustaining the intervention over time, then those strategies should be utilized at this point.

Phases 1–3: Planning for Dissemination

The implementation planning team should consider how various types of information can be disseminated and to whom information should be disseminated throughout the three phases described in the IPA Tool. During Phase 1, dissemination focuses on initial sharing of information about the intervention to increase awareness and buy-in from key interested parties. During Phase 2, dissemination efforts are focused on sharing implementation plans and tools with key interested parties. During Phase 3, dissemination includes, but is not limited to, sharing information with key interested parties that will support sustainment, and possibly spread, of the intervention. In addition, after the clinical trial ends, the IPA team will facilitate dissemination and translation of trial results beyond traditional strategies of journal publication and study summaries to increase adoption of the intervention, thereby improving the clinical care of Veterans and/or by improving VHA policy. Dissemination helps increase opportunities for bidirectional communication between the implementation assessment team and interested parties and the likelihood that results from this research will be adopted by national program offices and national organizations via evidence-based guidelines.

CSP Case Study Using the IPA Tool

The Veterans Individual Placement and Support Toward Advancing Recovery (VIP-STAR) was a VA CSP multicenter, prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of Individual Placement and Support (IPS) vs. usual care transitional work in unemployed Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD. The study found that, as hypothesized, more Veterans in the IPS group became steady workers (primary outcome) and earned more income from competitive jobs (secondary outcome) over the 18-month follow-up compared with the transitional work group [Reference Davis, Kyriakides and Suris12].

From its inception, the study incorporated a collaborative partnership between the clinical and research team(s) at each of the participating sites. Sites were selected based on qualifications of local site investigators, a previous track record of success with implementation of IPS for the serious mentally ill population, and a well-established and operational transitional work program. While the CSP Planning Committee did not include an implementation scientist, members did include IPS trainers, fidelity monitors, program evaluators, PTSD clinicians, and vocational rehabilitation experts. The IPA Tool would have provided the clinical trial planning committee with a roadmap to formulate a comprehensive inventory of employment-related resources and implementation challenges within the VA as well as approaches toward strategic involvement of VHA policy and clinical program leaders to align with the conclusions and results of the study. Using the tool may have better ensured that the positive results from the trial would more efficiently transform future service delivery. As indicated in the IPA Tool, interested parties should be provided with an opportunity to give input into the trial design and the structure of the treatment conditions so that end results could be trusted and embraced by all rather than elicit a threat to the status quo at the conclusion of the study (see Phase 1, item 6; Phase 2, item 3; Phase 3, item 1 in Table 2). In addition to input, the tool would have provided engagement and ownership of a robust process by both the VA research enterprise and VA clinical services acting in synergy so as to facilitate commitment to ensuring deployment of interventions proven to be effective/efficacious within a short period of time post-trial conclusion. Involvement of the end-user of services, that is, the Veteran with PTSD-related employment issues, and medical center directors represent other missed opportunities in pre-trial planning that could have been addressed using the IPA Tool. As noted in the case example, a structured study-wide process to help attain broad implementation (e.g., implementation at all study sites once the clinical trial ends) was not designed prior to study launch for this intervention. This deficit in planning for implementation likely negatively impacted the sustainment of IPS at the 12 local sites. A key barrier to post-study implementation was lack of funding for the local site IPS specialists designated to serve the PTSD patient population. Precedent existed for VA to support an enterprise-wide rollout of IPS for Veterans with psychotic disorders (2005). The investigators assumed that a similar funding stream would materialize after the evidence emerged for the PTSD population. Had the tool been used prospectively, cost planning would have occurred that likely would have enabled planning to circumvent this barrier. Leadership changes at the national level contributed to an attrition in resources for IPS sustainment which resulted in diminished focus on expanding services and/or ongoing quality monitoring across the board. No benchmarks of successful implementation were drafted and the trialists note (see Table 2, phase 2, section 5) that future implementation projects should include these measures of success: number of Veterans referred for and engaged in IPS services per month, number and duration of competitive jobs gained per participant, income earned per participant, patient satisfaction surveys, IPS fidelity scale scores, and job satisfaction scores.

Discussion

VA considers itself a Learning Health System dedicated to applying evidence to improve healthcare [Reference Kilbourne, Jones and Atkins14,Reference Vega, Jackson and Henderson24,Reference Atkins, Kilbourne and Shulkin25]. Implementation science is an important component of VA’s transition to a LHS because it involves strategies to improve the rapid uptake of effective treatments into real-world practice. Incorporating principles of implementation science in clinical trials through the IPA Tool could help achieve Learning Health System goals [Reference Rubin, Silverstein and Friedman26] and ensure that research findings are relevant to health systems and patient and community interested parties. This assessment, which notably includes recurring ascertainment of patient preferences and perspectives, will help uncover important variables that impact quality of life for Veterans and patients and willingness to use an intervention, particularly for those with health behavior components or requiring patient consent. Likewise, the evaluation of clinician and non-clinical staff perspectives can help with scale-up and spread of successful trials by uncovering and weaving around clinician barriers. Through use of the IPA Tool, perspectives of the interested parties, including engagement of hospital leadership on whom uptake and implementation depends, will be understood, which will help to identify ways to navigate around competing priorities and constrained resources in health settings. Although this tool was designed and applied retrospectively in a VA healthcare setting, the principles on which the tool is based are drawn from the field of implementation science as a whole and, therefore, broader than the VA context alone. The areas of focus indicated in the tool can be applied to other healthcare settings with little work to adapt. Even in the case of a negative or ambiguous trial result, lessons can be learned about barriers and facilitators that can be extrapolated to like organizational contexts or similar trials. An implementation plan is designed and integrated into a study protocol a priori and agnostic of subsequent study results. Trial results that are either inconclusive or fail to reach statistical significance should not discount the utility of an implementation plan. An intervention could fail to show efficacy/effectiveness either because it simply does not work as assumed (effect size overestimated; mechanism of action incorrectly considered) or it could not work (uptake and adherence miscalculated). Having an implementation plan integral to the protocol sheds light on the latter issue. If barriers to uptake and adherence to the intervention are adequately addressed in the context of an implementation plan and yet the results do not provide evidence of its efficacy/effectiveness, this could point to the direction of an ineffective intervention. At the same time, implementation helps identify, upfront, structural, and process barriers that could potentially inform testing anew of a new/different/more efficacious/effective intervention.

Most current academic promotion pathways do not incentivize implementing treatments or findings into practice [Reference Kilbourne, Jones and Atkins14], nor do common funding mechanisms include support for implementation activities. The types of activities described in this manuscript and throughout the IPA Tool necessitate significant time and follow contrary to the general manuscript or grant funding mechanism. Resource allocation to programs such as that of QUERI program [Reference Kilbourne, Elwy and Sales8] and the Implementation Research Project (IRP) mechanisms needs to grow to incentivize these types of scientific inquiry. Likewise, funding agencies such as VA, NIH, and AHRQ should consider requiring plans for the phases covered in this IPA Tool for sustainment, scale-up, and spread, if the trials are found to be effective. This requirement would also necessitate that funding agencies increase funding to support development of implementation plans.

The CSP breadth of inclusion of implementation plans is evolving and spreading throughout their trials and over time. As the clinical trials arm operating within the VA’s large learning healthcare system, CSP is in a unique position to bridge, in a bidirectional way, the clinical and research arms of such a system. Utilizing implementation science and its robust methodology and tools, CSP can support the design, operation, management, execution, and analysis of definitive clinical trials, while at the same time ensure implementation, sustainability, and continuity of effective interventions resulting from its clinical trials. In addition, the ability of the clinical side of the VA system to identify clinically significant questions and then generate testable hypotheses with support from and in true partnership with the built-in CSP clinical trials operation allows for impactful research to be strategically planned and executed toward fulfilling the mission of improving Veteran healthcare through quick deployment and clinical setting adoption of such evidence-based research.

Given the case example represents a team that retrospectively applied the tool, we cannot yet provide an accurate estimate of how much effort will be needed to complete it prospectively, as intended. Our team is working with 2 clinical trials that are currently applying the tool prospectively and will have more information in the future about the time and effort needed to complete the tool. As mentioned earlier, the intention of the tool is not that the team should complete it all at once, but rather revisit as needed. It is up to the individual/s and team to determine how they want to use the tool and to what extent. Application of the tool will take some time. However, these efforts should help teams better integrate clinical trials and original research into clinical practice by proactively facilitating adoption of research results into routine care in a sustainable way.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this manuscript. First, the IPA Tool was designed to provide trialists and interested parties in the outcomes with practical guidance on how to include implementation planning in clinical trials. However, the IPA Tool may not describe all aspects of implementation planning. Therefore, we encourage users of the IPA Tool to consider how to tailor the steps in the checklist dependent on the type of trial, effectiveness, or efficacy, as the applications can vary depending on trial type. Second, the retrospective use of this tool for the case example had limitations since some of the phases were not addressed during the CSP trial. However, the CSP trialists who completed the case example were able to reflect on the phases that were completed and then describe missed or future opportunities for improving implementation planning. The team believes that if the IPA Tool has been available much of the trial-and-error approach could have been avoided. In addition, since CSP trials have only recently been matched with implementation scientists, they did not have data to complete all three phases of the IPA Tool. Though the IPA Tool may have a greater impact if used prospectively, our case example suggests there are also benefits of using the tool retrospectively.

Conclusion

The IPA Tool brings a ready-made list of necessary steps for clinical trialists aiming to improve implementation, including scale-up and spread, of effective, clinical trial-tested interventions in healthcare settings. The IPA Tool was designed to help catapult the field of clinical trial inquiry into a new realm of applied practice. Likewise, the IPA Tool can also be utilized by practitioners, clinicians, and researchers who are new to the field of implementation science and the involved processes to help with grant writing and throughout the life of their implementation trials.

Acknowledgements

There are no funders to report.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests to declare.