Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are conditions in which individuals are born, reside, engage in employment, acquire knowledge, practice religion, enjoy recreational activities, and grow old [1]. Taken together, SDoH are a well-established classification of essential non-medical factors that directly or indirectly impact health outcomes [Reference Sulley and Bayssie2,Reference Ansari, Carson, Ackland, Vaughan and Serraglio3]. These factors may impact access to health care and may be related to individual behaviors as well as disease biology with important implications to an individual’s health [Reference Sulley and Bayssie2,Reference Ansari, Carson, Ackland, Vaughan and Serraglio3]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how patients in vulnerable socioeconomic contexts were at heightened risk of disease transmissibility, hospitalization, and mortality [Reference Brakefield, Olusanya, White and Shaban-Nejad4]. In response to the exacerbation of longstanding health disparities during the pandemic, there has been an increased interest in methods to identify and define SDoH [Reference Brakefield, Olusanya, White and Shaban-Nejad4,Reference Nana-Sinkam, Kraschnewski and Sacco5]. By accessing data on SDoH, there is the potential to implement policies and target interventions to address barriers to health and healthcare delivery [Reference Andermann6]. Importantly, resolving unmet social needs that underpin SDoH represents an opportunity to meaningfully improve population health, quality of life, and life expectancy, as well as patient outcomes [Reference Byhoff, Guardado, Xiao, Nokes, Garg and Tripodis7].

Personal and systemic factors compromise a wide range of social determinants of health that drive health outcomes [Reference Johnson, Luther, Wallace and Kulesa8–Reference Braveman and Gottlieb12]. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies SDoH into five broad domains: economic stability, education, social and community context, health care access and quality, and neighborhood and built environment [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13]. In addition to these broad domains, additional dimensions include – but are not limited to – race and ethnicity, housing, food security, transportation, violence and safety, employment, health behaviors (i.e., substance use, physical activity, and dietary choices), mental health, disabilities, religion, immigration status, legal concerns, gender, and sexual orientation.[Reference Khatib, Glowacki, Byrne and Brady14,Reference Wray, Tang, López, Hoggatt and Keyhani15] For instance, substandard housing has been associated with a higher prevalence of respiratory, hematologic, and neurologic illness, as well as childhood lead poisoning [16].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated healthcare disparities [17,Reference Andraska, Alabi and Dorsey18], drawing attention to the need to develop federal and community-based policies to improve health equity. The recently issued United States Domestic Policy Counsel Playbook outlined recommendations for federal agencies to improve policies around SDoH with an emphasis on identifying social metrics relevant to health outcomes [17]. The Playbook served as a call to stakeholders and agencies to develop actionable programmatic changes to quantify and improve SDoH metrics. Proposed reforms are intended to occur at the federal and local levels to support community organizations to institute patient-level screening. These broad changes also seek to achieve a secondary goal: easing the substantial economic burden of health expenditures that occur due to pervasive health inequity [Reference Buitron de la Vega, Losi and Sprague Martinez19,Reference Sandhu, Lian, Smeltz, Drake, Eisenson and Bettger20]. Concurrent with these initiatives, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have mandated that hospitals implement two new measures in 2024 to screen patients for SDoH: SDoH-1 or Screening for Social Drivers of Health and SDoH-2 or Screen Positive Rate for Social Drivers of Health [21]. While mandating reporting of SDoH measures, CMS does not offer uniform data-capturing methods/approaches, instead giving hospitals flexibility/discretion in how SDoH characteristics are recorded.

Screening tools intended to capture data on SDoH can vary significantly with vastly different domains, which may complicate how data are collected and used to develop community interventions to address health inequities [Reference Freij, Dullabh, Lewis, Smith, Hovey and Dhopeshwarkar22,Reference Cantor and Thorpe23]. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to report on available SDoH screening tools in a systematic manner aimed at addressing disparities identified using these tools.

Methods

Search methods

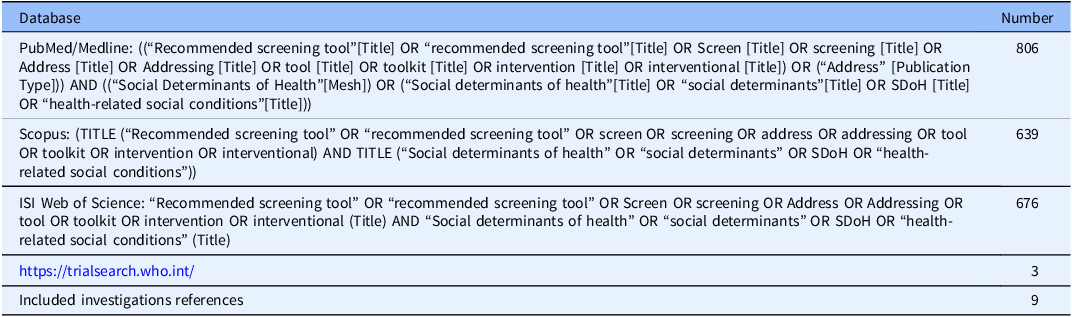

The study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO, an internationally recognized database for prospectively registered systematic reviews in the fields of health and social care [Reference Page, McKenzie and Bossuyt24]. A comprehensive search of the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases from 1980 to November 2023 was performed using predetermined keywords. The search included a mix of subject headings and keywords that related to different social determinants screening tools, as well as specific proposed SDoH addressing interventions (Table 1). In addition to searching PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, a search of “grey literature” sources was also performed based on references of relevant studies, as well as an international clinical trials registry platform to identify parallel and ongoing research. Inclusion criteria included: (a) written in the English language, (b) conducted in the United States, and (c) established a screening tool to identify or address SDoH. Reviews and reports with no publicly accessible survey tool were excluded. Studies that fulfilled inclusion criteria reported data from 2007 to 2023, and each study provided an SDoH screening tool or an SDoH intervention. All reports initially identified from the database search were entered into ENDNOTE software for analysis.

Table 1. Search strategy and keywords used for literature screening

Results

Study characteristics

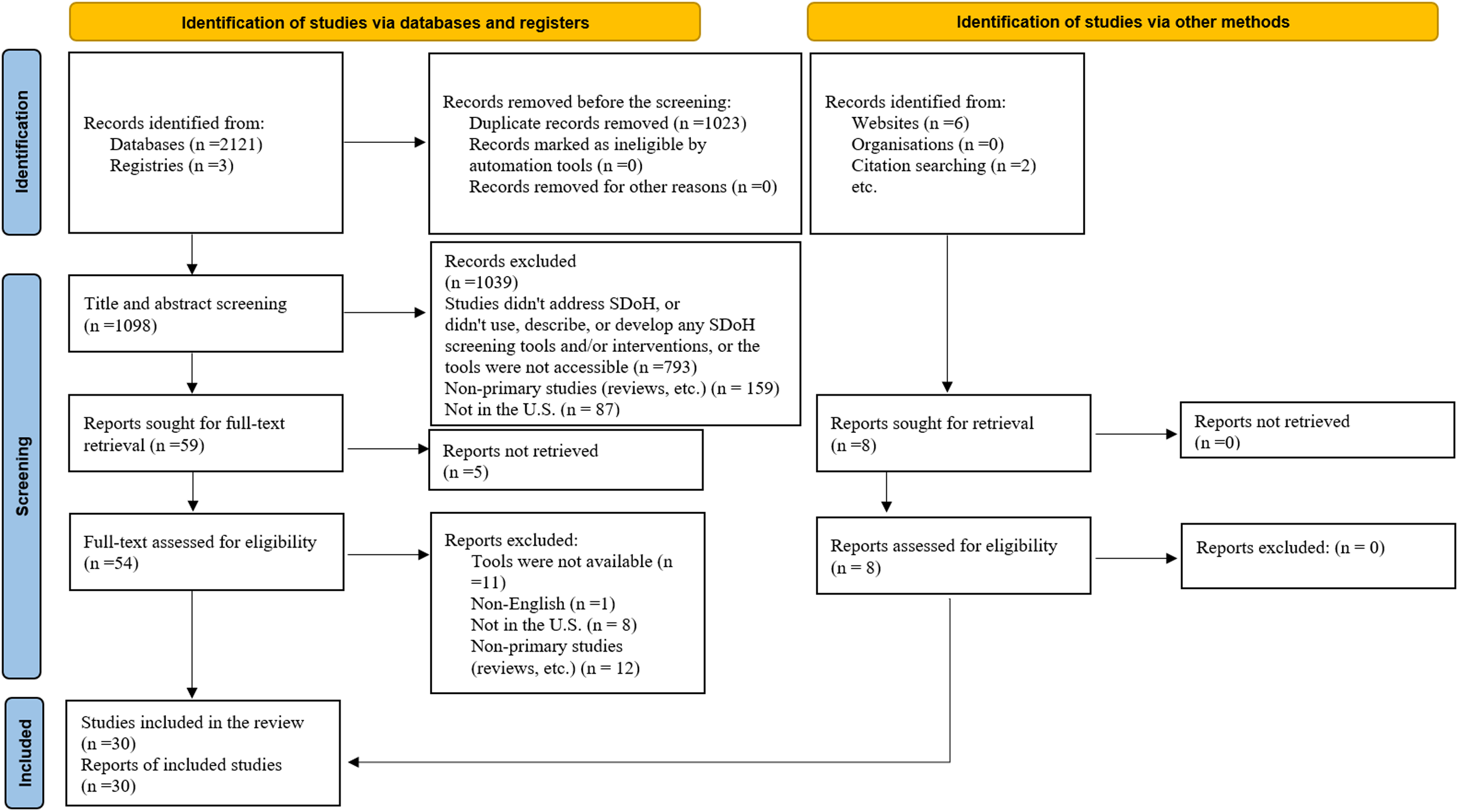

The initial search identified 2,121 studies. After eliminating duplicate entries, a total of 1,098 studies underwent primary screening. Following title and abstract screening, studies that did not address SDoH, or did not propose any publicly accessible SDoH screening tools and/or interventions (n = 793), were excluded. In addition, non-primary studies (reviews, etc.) (n = 159) and studies that were not conducted in the USA (n = 87) were excluded. A total of 59 studies were sought for full-text retrieval. Following a secondary review of these 59 full texts, 22 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Greenwood-Ericksen, DeJonckheere, Syed, Choudhury, Cohen and Tipirneni25–Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45]. Following a manual search of the literature, as well as after snowballing the citations of included studies, 8 additional articles were incorporated into the review [46–53]. As such, a total of 30 papers were included in the analytic cohort (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) demonstrating selection of studies included in the analytic cohort.

Screening tools characteristics

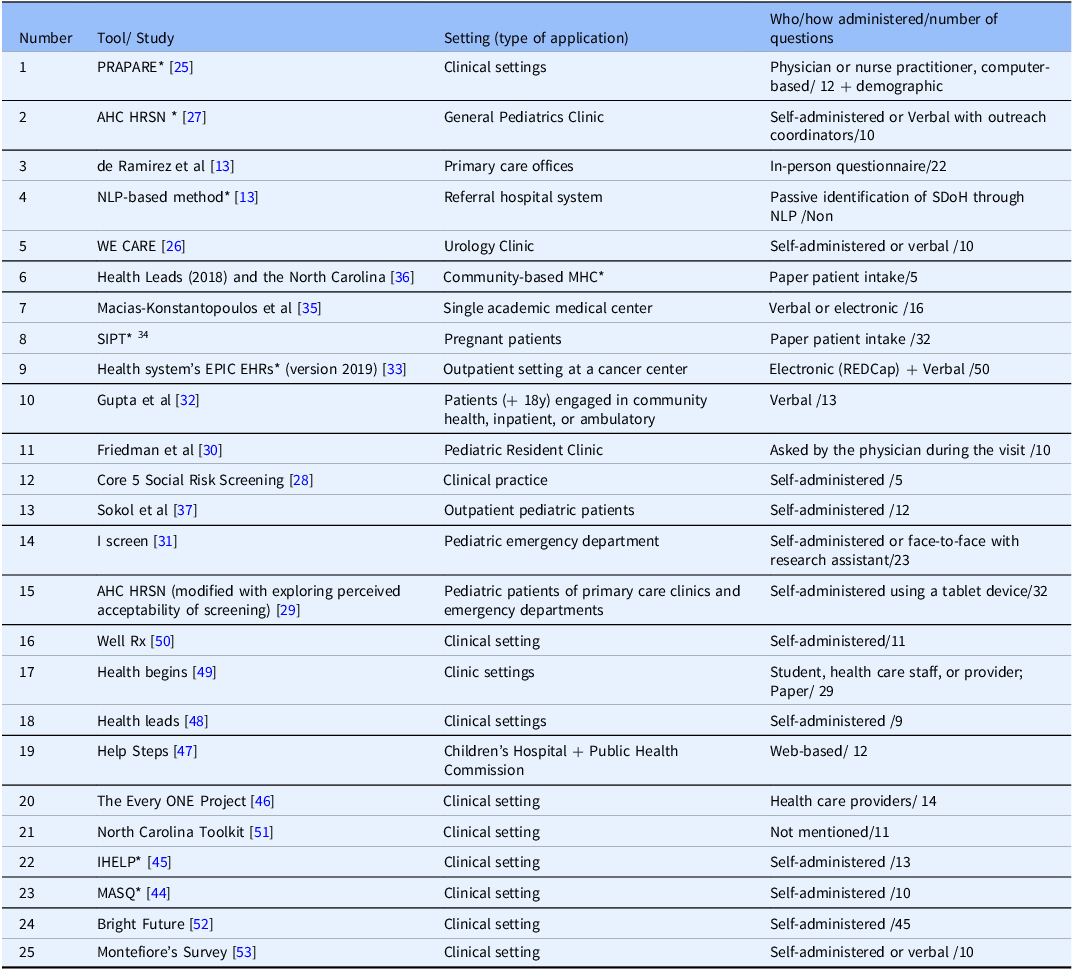

Table 2 describes the SDoH screening tool characteristics of the 25 unique screening tools that were identified. Six screening tools were administered to pediatric patients [Reference Yaun, Rogers, Marshall, McCullers and Madubuonwu27,Reference De Marchis, Hessler and Fichtenberg29–Reference Gottlieb, Hessler, Long, Amaya and Adler31,Reference Sokol, Mehdipanah, Bess, Mohammed and Miller37,Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47]. One was designed to assess pregnant patients [Reference Harriett, Eary and Prickett34], and the remaining tools (n = 18) were utilized for general screening purposes in clinical settings, such as hospitals or clinical offices [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Greenwood-Ericksen, DeJonckheere, Syed, Choudhury, Cohen and Tipirneni25,Reference Roebuck, Urquieta de Hernandez and Wheeler26,Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28,Reference Gupta, Self, Thomas, Supra and Rudisill32,Reference Hao, Jilcott Pitts and Iasiello33,Reference Macias-Konstantopoulos, Ciccolo, Muzikansky and Samuels-Kalow35,Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36,Reference Elsborg, Nielsen, Klinker, Melby, Christensen and Bentsen38–46,48–53] Six tools were administered by healthcare professionals [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Greenwood-Ericksen, DeJonckheere, Syed, Choudhury, Cohen and Tipirneni25,Reference Friedman, Caddle, Motelow, Meyer and Lane30,Reference Gupta, Self, Thomas, Supra and Rudisill32,46,49]; while 12 tools were completed by patients (or parents) either electronically or on paper [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28,Reference De Marchis, Hessler and Fichtenberg29,Reference Harriett, Eary and Prickett34,Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36,Reference Sokol, Mehdipanah, Bess, Mohammed and Miller37,Reference Keller, Jones, Savageau and Cashman44,Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45,Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47,48,Reference Page-Reeves, Kaufman and Bleecker50,52]; six tools were administered verbally or were self-administered at the patient’s request [Reference Roebuck, Urquieta de Hernandez and Wheeler26,Reference Yaun, Rogers, Marshall, McCullers and Madubuonwu27,Reference Gottlieb, Hessler, Long, Amaya and Adler31,Reference Hao, Jilcott Pitts and Iasiello33,Reference Macias-Konstantopoulos, Ciccolo, Muzikansky and Samuels-Kalow35,53]; The number of questions in any given SDoH assessment tool varied considerably and ranged from 5 in Health Leads (2018) and the North Carolina toolkit [Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36], as well as the Core 5 social risk tool [Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28] to 50 in the health system’s EPIC electronic health records screening tool [Reference Hao, Jilcott Pitts and Iasiello33]; overall, the mean number of questions in any given SDoH screening tool assessment was 16.6 (Table 2).

Table 2. SDoH screening tool characteristics of the 25 unique screening tools that were identified

SDoH = social determinants of health; PRAPARE = Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences; AHC = Accountable Health Communities; HRSN = Health-Related Social Needs; NLP = natural language processing; MHC = Mobile Health Clinic; WE CARE = Welcome, Engage, Communicate, Ask, Reassure, Exit; SIPT = Social Determinants of Health in Pregnancy Tool; EHRs = electronic health records; IHELP = Income, Housing, Education, Legal Status, Literacy, Personal Safety; MASQ = Medical-legal Advocacy Screening Questionnaire.

Tools comprehensiveness

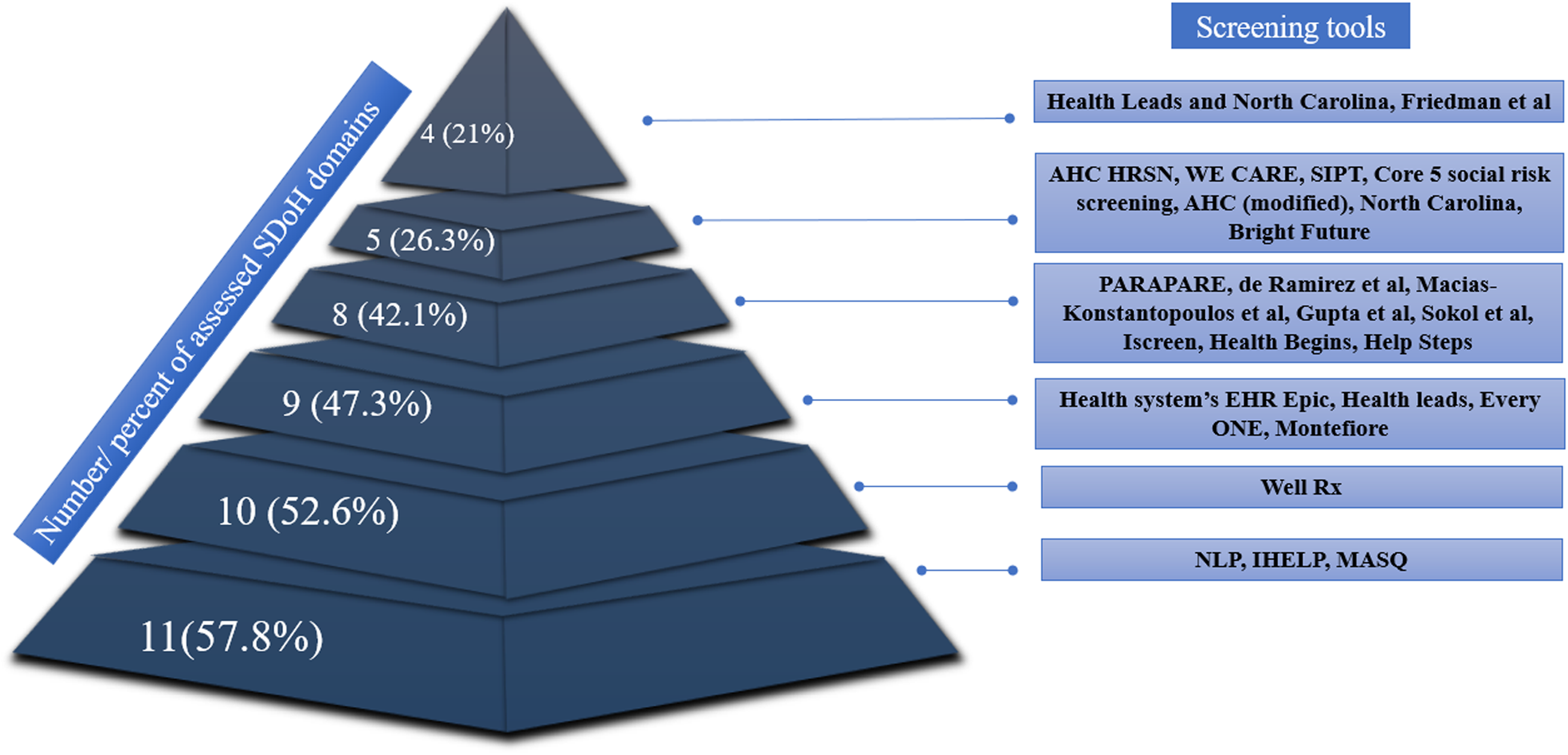

A total of 19 distinct SDoH domains were examined in the various screening tools (Fig. 2). Various screening tools evaluated different domains, ranging from four domains (21%) in Health Leads and the North Carolina [Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36], and Friedman et al. screening tools [Reference Friedman, Caddle, Motelow, Meyer and Lane30], to 11 (57.8%) within the natural language processing (NLP) [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13], Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Literacy, Personal safety (IHELP) [Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45], and Medical-legal advocacy screening questionnaire (MASQ) [Reference Keller, Jones, Savageau and Cashman44] tools (Fig. 3). The Well Rx tool [Reference Page-Reeves, Kaufman and Bleecker50] evaluated 10 SDoH domains (52.6%), while the EPIC EHR [Reference Hao, Jilcott Pitts and Iasiello33], Health leads [48], EveryONE project [46], and Montefiore [53] tools evaluated 9 domains (47.3%). Eight SDoH domains (42.1%) were evaluated in Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PARAPARE) [Reference Greenwood-Ericksen, DeJonckheere, Syed, Choudhury, Cohen and Tipirneni25], as well as the tools proposed by de Ramirez et al., [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13] Macias-Konstantopoulos et al., [Reference Macias-Konstantopoulos, Ciccolo, Muzikansky and Samuels-Kalow35] Gupta et al., [Reference Gupta, Self, Thomas, Supra and Rudisill32] Sokol et al. [Reference Sokol, Mehdipanah, Bess, Mohammed and Miller37] The Iscreen [Reference Gottlieb, Hessler, Long, Amaya and Adler31]. Health Begins [49], Help Steps surveys [Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47]. Tools such as Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs (AHC HRSN) [Reference Yaun, Rogers, Marshall, McCullers and Madubuonwu27], Welcome, Engage, Communicate, Ask, Reassure, Exit (WE CARE) [Reference Roebuck, Urquieta de Hernandez and Wheeler26], Social Determinants of Health in Pregnancy Tool (SIPT) [Reference Harriett, Eary and Prickett34], Core 5 social risk screening [Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28], Accountable Health Communities (modified) [Reference De Marchis, Hessler and Fichtenberg29], North Carolina [51], and Bright Future [52] examined 5 domains of SDoH (26.3%). Four screening tools (16%) evaluated at least 10 (52.6%) different SDoH domains (Well Rx [Reference Page-Reeves, Kaufman and Bleecker50], NLP [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13], IHELP [Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45], MASQ [Reference Keller, Jones, Savageau and Cashman44]), while the remaining screening tools (n = 21, 84%) evaluated fewer SDoH domains (Table 3).

Figure 2. Various SDoH domains that may impact patient health. SDoH = social determinants of health.

Figure 3. Relative number of SDoH domains assessed in the various screening tools. SDoH = social determinants of health; AHC = Accountable Health Communities; HRSN = Health-Related Social Needs; WE CARE = Welcome, Engage, Communicate, Ask, Reassure, Exit; SIPT = Social Determinants of Health in Pregnancy Tool; PRAPARE = Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences; EHRs = electronic health records; NLP = natural language processing; IHELP = Income, Housing, Education, Legal Status, Literacy, Personal Safety; MASQ = Medical-legal Advocacy Screening Questionnaire.

Table 3. Domains assessed by each screening tool

PRAPARE = Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patient Assets, Risks, and Experiences; AHC = Accountable Health Communities; HRSN = Health-Related Social Needs; NLP = Natural Language Processing; MHC = Mobile Health Clinic; WE CARE = Welcome, Engage, Communicate, Ask, Reassure, Exit; SIPT = Social Determinants of Health in Pregnancy Tool; EHRs = Electronic Health Records; IHELP = Income, Housing, Education, Legal status, Literacy, Personal Safety; MASQ = Medical-legal Advocacy Screening Questionnaire.

SDoH domains

While no individual SDoH domain was assessed in every screening tool, housing (n = 23, 92%) and safety/violence (n = 21, 84%) were the domains assessed most frequently examined (Fig. 4). SDoH domains involving food/nutrition (n = 17, 68%), income/financial (n = 16, 64%), transportation (n = 15, 60%), family/social support (n = 14, 56%), utilities (n = 13, 52%), and education/literacy (n = 13, 52%) were also commonly included in most SDoH screening tools. Other SDoH domains that were commonly assessed in the various screening tools included employment (n = 10, 40%), substance/smoke/alcohol use (n = 8, 32%), stress/mental issues (n = 6, 24%), child/elder care (n = 7, 28%), and legal concerns (n = 7, 28%). In contrast, race/ethnicity (n = 4, 16%), healthcare access/insurance (n = 4, 16%), moving/transience (n = 3, 12%), neighborhood (n = 3, 12%), disability (n = 1, 4.0%), and physical activity (n = 1, 4.0%) were the least commonly assessed domains among the different SDoH screening tools.

Figure 4. Specific SDoH domain themes that were assessed among the different SDoH screening tools. SDoH = social determinants of health.

SDoH-based interventions

Of note, 18 studies not only screened SDoH but also proposed specific interventions aimed at addressing SDoH (Supplemental Table 1) [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Roebuck, Urquieta de Hernandez and Wheeler26–Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28,Reference Friedman, Caddle, Motelow, Meyer and Lane30,Reference Gupta, Self, Thomas, Supra and Rudisill32–Reference Harriett, Eary and Prickett34,Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36–Reference Henwood, Cabassa, Craig and Padgett43,Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47,Reference Page-Reeves, Kaufman and Bleecker50]. Twelve screening tools identified patient preferences toward receiving supplementary assistance relative to the SDoH identified. If the response was affirmative, referral to relevant social workers was made based on the positive domain that had been identified on screening [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Roebuck, Urquieta de Hernandez and Wheeler26–Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28,Reference Friedman, Caddle, Motelow, Meyer and Lane30,Reference Gupta, Self, Thomas, Supra and Rudisill32–Reference Harriett, Eary and Prickett34,Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36,Reference Sokol, Mehdipanah, Bess, Mohammed and Miller37,Reference Gurewich, Garg and Kressin39,Reference Page-Reeves, Kaufman and Bleecker50]. Interestingly, three separate studies proposed interventions grounded in sports [Reference Elsborg, Nielsen, Klinker, Melby, Christensen and Bentsen38], sleep health [Reference Hale, Troxel and Buysse40], and developing a national agenda aimed at homelessness and homeless individuals to address SDoH [Reference Henwood, Cabassa, Craig and Padgett43]. Fleegler et al. had patients utilize a web-based application entitled Help Steps to not only self-identify social needs but also identify community-based support for those needs identified [Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47]. In a different study, Hassan et al. implemented a web-based tool for patients to assess SDoH domains, offering feedback and assistance in choosing appropriate agencies, and follow-up using phone calls [Reference Hassan, Scherer and Pikcilingis41]. In another study, Hatef et al.[Reference Hatef, Weiner and Kharrazi42] developed an electronic health record (EHR)-derived community health record that aggregated data at both the hospital and neighborhood level as a means to capture local community health data at the population level, identify SDoH needs, and then link community-based resources to address patient needs.

Discussion

SDoH represents a broad array of domains that can impact a patient’s lived experiences, including their overall well-being and health. Growing evidence has demonstrated that addressing unmet health-related social needs such as hunger, exposure to violence, homelessness, and transportation can help improve well-being [54]. While health providers routinely use clinical assessment algorithms, tools to screen SDoH have not been as widely adopted or implemented [Reference Bradywood, Leming-Lee, Watters and Blackmore28]. Collection of such data may inform patient treatment plans and referrals to community services [Reference Moen, Storr, German, Friedmann and Johantgen55]. When patients screen positive for particular social risks and social needs, targeted interventions may help address disparities and improve health equity. As such, CMS has mandated that hospitals screen patients for SDoH [21]. The means and methods to capture these data have not been well defined, however, with no single screening tool being universally adopted or available. The current study was important as we performed a systematic review of various screening tools published in the literature to identify and target SDoH in the clinical setting. Of note, the various screening tools were heterogeneous in their use, application, scope of inquiry, and targeted domains of SDoH. Many of the screening tools included a different number of SDoH domains, as well as variable domain types. Specifically, the median number of domains evaluated in SDoH screening tools was 8.0 (interquartile range, 9.0-5.0) with housing and safety/violence being the domains assessed most frequently (Fig. 4). Food/nutrition, income/financial, transportation, family/social support, utilities, and education/literacy were also commonly included in many SDoH screening tools. While less frequent, some reports utilized the SDoH identified in the screening tools to inform some type of intervention. For instance, sports-based interventions were proposed to improve personal physical and psychosocial health [Reference Elsborg, Nielsen, Klinker, Melby, Christensen and Bentsen38], while other studies proposed web-based applications and/or linking the EMR to community databases to identify community-based support for those needs identified on screening [Reference Hassan, Scherer and Pikcilingis41,Reference Hatef, Weiner and Kharrazi42,Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47].

Among the tools with explicitly defined criteria, the NLP [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13], IHELP [Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45], and MASQ [Reference Keller, Jones, Savageau and Cashman44] screening tools were the most comprehensive in their approach as these tools included the highest number of SDoH domains. The NLP algorithm system utilized the existing electronic medical record and identified keywords or phrases that suggested housing or financial needs (i.e., lack of permanent address); the NLP model performed with high accuracy. NLP combines computational linguistics with machine and deep learning models [56]. In turn, large amounts of EMR text data can be processed to understand its meaning and identify different themes including the risk of adverse SDoH. Adverse social SDoH may include social risks associated with poor health (e.g., food insecurity), and individual preferences and priorities regarding seeking assistance to address the social needs (e.g., seeking food assistance) [Reference Samuels-Kalow, Ciccolo, Lin, Schoenfeld and Camargo57]. An NLP approach is limited, however, in that it can only assess textual data that had been recorded in the EMR by healthcare providers. In contrast, SDoH screening questionnaires provide an opportunity to query patients specifically about different SDoH domains. The IHELP questionnaire focused on pediatric patients and queried SDoH domains such as income, housing/utilities, education, legal status/immigration, literacy, and personal safety [Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45]. In turn, data collected from this questionnaire may elicit specific environmental, legal, and psychosocial risk factors that can be utilized by social workers to address the needs of individual patients. For example, the use of the MASQ screening tool was able to identify families of pediatric patients who required assistance with legal services and help facilitate a referral [Reference Keller, Jones, Savageau and Cashman44]. Therefore, the use of screening tools can pinpoint the different SDoH domains needed by patients to allocate limited resources to serve that specific need.

Several tools such as the Health Leads and the North Carolina survey [Reference Mullen, Oermann, Cockroft, Sharpe and Davison36], as well as the screening tool proposed by Friedman et al., [Reference Friedman, Caddle, Motelow, Meyer and Lane30] focused on four domains including housing, safety/violence, family/social support, and substance/smoke/alcohol misuse. Other tools concentrated on screening for economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, as well as social and community context [Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45,53]. Of note, IHELP was the only screening tool that addressed all five main SDoH domains identified by WHO [Reference Stewart de Ramirez, Shallat, McClure, Foulger and Barenblat13,Reference Kenyon, Sandel, Silverstein, Shakir and Zuckerman45]. Housing and safety/violence were the most frequently assessed domains among the screening tools. These SDoH themes highlight how housing insecurity plays a significant role in health status as overcrowding, frequent relocation, and housing expenses can negatively impact health [Reference Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling and Taylor58,Reference Rolfe, Garnham, Godwin, Anderson, Seaman and Donaldson59]. In turn, helping patients secure housing can improve health through multiple mechanisms, including increasing patient safety [Reference Henwood, Cabassa, Craig and Padgett43]. Exposure to unsafe environments can have long-term health consequences, including amplifying chronic diseases and mental illnesses [Reference Moffitt60]. In addition, themes of food/nutrition, income/financial concerns, as well as transportation and education/literacy were other frequently evaluated domains across various assessment tools (Table 3). Interestingly, although repeatedly associated with increased risk of social vulnerability and adverse SDoH, race/ethnicity was often not included in screening tools – perhaps because these data are required already as part of the “meaningful use” of electronic health records [Reference Klinger, Carlini and Gonzalez61].

Beyond proposing and implementing screening tools, several authors proposed interventions to address adverse SDoH. Overall, a total of 18 interventions in addition to primary SDoH screening were identified (Supplemental Table 1). Most interventions consisted of referring individuals to social health workers, who were selected based on the specific SDoH identified through the screening process. For example, Fleegler et al. used the SDoH screening tool to identify specific patient needs and then delivered assistance using a web-based application, which recommended specific community-based agencies [Reference Fleegler, Bottino, Pikcilingis, Baker, Kistler and Hassan47]. In a similar manner, Hassan et al. proposed a different web-based tool that provided patient feedback and assistance in choosing appropriate agencies based on the SDoH screening tool as well as performing follow-up using telephone calls [Reference Hassan, Scherer and Pikcilingis41]. Utilization of web-based tools may serve to connect patients to resources based on needs identified through SDoH screening. Web-based tools may need to be supplemented, however, with patient navigators, lay community health care workers, as well public health workers who can serve as a bridge between communities, health care systems, and state health departments.

One of the main strengths of this review is that no other study has performed a thorough evaluation and comparison of available screening tools to address SDoH in the United States to date. Nevertheless, due to the heterogeneity of the tools and the diverse target populations evaluated by each individual screening tool, future efforts should aim at defining best practices in collecting SDoH, as well as identifying standardized means to report SDoH in a timely manner. In addition, despite the available screening tools, future efforts should aim at not only reporting but also addressing social needs and mitigate disparities in access to high-quality care.

In conclusion, CMS has mandated evaluation of SDoH to identify medical and social barriers that impede the health and well-being of patients [21]. SDoH and associated health disparities are important drivers of healthcare access and outcomes [Reference Park, Mulligan, Gleize, Kristiansen and Bettencourt-Silva62]. SDoH screening tools are critical to identify various social needs and vulnerabilities so that patients can be connected to effective interventions to address their needs [Reference Jain and Chandrashekar63]. The current systematic review demonstrated the heterogeneity of currently available SDoH screening tools, as well as the variability in the SDoH domains assessed. The use of technology via web-based screening platforms and the electronic medical records is critical to capture patient SDoH, as well as potentially link individuals with community resources. Patient navigators and public health community workers also play an important role in connecting patients with resources.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2024.506.

Author contributions

T.M.P.: Supervision, conceptualization, designation, data collection, analysis, and revising the review; M.N.: original draft preparation, writing, reviewing, editing, data collection, and analysis; N.F.: data collection, analysis, review, and editing the manuscript; V.P., D.I.T., and S.O.G.: review and editing of the manuscript; and T.M.P.: takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Competing interests

None.