1. Introduction

There is a vast and still growing literature on resultatives. They play center stage in construction grammar (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, chapter 8; Goldberg & Jackendoff Reference Goldberg and Ray2004) and related frameworks, such as Simpler Syntax (Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Ray2005, chapter 4, section 5) but also in lexicalist Montague grammar (Dowty Reference Dowty1979, chapter 2), LFG (Simpson Reference Simpson, Lori, Malka and Annie1983), HPSG (Müller Reference Müller2002, chapter 5), transformational grammar (Thompson Reference Thompson1973), Government and Binding Theory (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra1988; Carrier & Randall Reference Carrier and Janet1992; den Dikken Reference Dikken1995, chapters 2, 3, and 5), and Minimalism (Snyder Reference Snyder2001). The present study is a contribution to this body of work focused on a particular reading of certain resultatives. Our observations lead to similar conclusions, regardless of analytical framework.

The resultatives at issue here form a small but growing group of expressions with an intensifying function that are productive in a range of patterns. Henceforth, we refer to them as DEGREE RESULTATIVES. To see the difference between ordinary and degree resultatives, consider 1.

(1)

Structurally, 1a and 1b are alike (transitive, with a PP within the VP), but semantically they differ. In 1a, the resultative is literal: off the book is predicated of the direct object the dust and expresses the state that results from Jones’s wiping action. In contrast, 1b is not literally talking about Smith removing excrement from Jones’ body, but about the intensity of the beating (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Donna2008, Haïk 2012, Perek Reference Perek2016). That is, out of Jones is not predicated of the direct object the crap. The expression in 1b is idiomatic, but it follows a productive pattern: One could substitute for beat verbs such as hit, bash, whack, kick, club, bludgeon, trample, clobber, and other verbs of contact-by-impact (Levin Reference Levin1993) or verbs such as annoy, irritate, bug, and other psych verbs (Sells Reference Sells1987). In such examples, the constructional contribution to the interpretation of the verb phrase is intensification (Gyselinck & Colleman Reference Leeson and John2016a,Reference Gyselinck and Timothyb, Gyselinck Reference Gyselinck2018).

To account for resultatives such as in 1b, we introduce the concept of SECOND-ORDER CONSTRUCTIONS. Such constructions, at least initially, rely on corresponding first-order constructions for their interpretation (somewhat similar to secondary grammaticalization, as in Givón Reference Givón, Elizabeth and Bernd1991, Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Graeme2013). That is, the degree interpretation of 1b is available because the literal interpretation of 1a is available. Second-order constructions, then, are derived from first-order constructions.

The emergence of second-order constructions is largely unpredictable: One cannot predict, in any given language, which first-order constructions would lead to second-order constructions. Yet it is possible to draw generalizations about particular (groups of) lexical items that appear in second-degree constructions. In case of degree resultatives, we demonstrate that they frequently involve taboo expressions referring to sex, defecation, bodily effluents, as well as various euphemisms. They also contain expressions describing death, disease, mental illness, and loss of body parts. However, which particular expressions are used in which constructions is largely arbitrary and language-specific, as our comparison of English and Dutch degree resultatives shows.

In a first-order construction, meaning is determined by the component lexical items, plus the constructional meaning contribution. In a second-order construction, the original constructional meaning is overwritten by a new interpretation, while the old interpretation, including the meaning of individual parts, is still potentially available, but far less readily. In 1b, the degree interpretation is the natural/salient one, but the literal, resultative interpretation is still accessible, though unlikely. Example 1b contains an ordinarily transitive verb, beat. The form verb + [the + taboo term] + out of NP is an intensified variant of the form verb + NP, that is, beat Jones. In the former pattern, the expletive is the direct object; in the latter pattern, NP is the direct object; and in both, the NP Jones is the patient argument of the verb. Example 1b in its literal, resultative reading belongs to the class of caused motion constructions: An agent causes an object to change location. However, in its second-order reading, it is an intensification of an action (beating) involving an agent and a patient.

Resultative predicates can also intensify the meaning of verbs that are typically intransitive:

(2)

Example 2a has the form verb + reflexive + XP. The resultative predicate (here sick) often denotes death, dismemberment, sickness, and other taboo topics (on the intimate relation between taboo expressions, intensification, and pejoratives, see Napoli & Hoeksema Reference Napoli and Jack2009). Example 2b, in contrast, has the form verb + possessive pronoun + body part + off (a somewhat productive pattern; Cappelle Reference Cappelle2014).Footnote 1 The possessive pronoun of 2b, like the reflexive of 2a, is bound by the subject.

Resultative predicates that have a degree interpretation act as intensifiers. Dutch has various types of these intensifying degree resultatives. Some are very much like English—compare 3 to 2a.

(3)

Dutch also has intensifying degree resultatives that make reference to body parts, similar to English 2b, but with a reflexive instead of a possessive pronoun. About cases such as 3, Broekhuis et al. (2015:254) remark that “they mainly bring about an amplifying effect.” They note that the same can be said about ditransitives such as in 4, analyzed in Cappelle Reference Cappelle2014.Footnote 2

(4)

In 4, one finds two NPs within the VP, neither of which is inside a PP; this is the structural configuration we mean when we use the term ditransitive. Datives in the double object construction appear in this configuration as well. Some have argued, at least for English, that dative constructions form part of a larger set of constructions that includes resultatives (Snyder & Stromswold Reference Snyder and Karin1997; but see Carrier & Randall Reference Carrier and Janet1992, appendix). We do not, however, include datives in our discussion (whether in the double object construction or in PPs), because we have come across no examples of dative constructions that have a degree interpretation.

We treat ditransitives such as in 4 as a special case of resultatives. This analysis of 4 is coherent with the common view of resultatives, ditransitives, and directed motion constructions as all involving change along a (metaphorical) path (Simpson Reference Simpson, Lori, Malka and Annie1983, Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra1984, Larson Reference Larson1988, Levin & Rappaport Hovav Reference Levin, Malka, Beth and Steven1991, Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995, den Dikken Reference Dikken1995, Hale & Keyser Reference Hale and Samuel1996). These three constructions cannot co-occur within a clause: In the same way that a resultative predicate cannot be added to a resultative construction that already contains a resultative predicate (apart from conjunction), it cannot be added to a ditransitive or directed motion construction, as shown in 5 (examples adapted from Goldberg Reference Goldberg1995:82).

(5)

Semantically, resultatives (including ditransitives) can often be analyzed as part of a complex construction containing a CAUSE predicate.Footnote 3 For example, wipe the table clean means that the actor causes the table to become clean by wiping, while give someone a present means that the actor causes someone to have a present (Harley Reference Harley2002). The same is true for caused motion: drive the truck to Atlanta means that the driver causes the truck to be in Atlanta (Dowty Reference Dowty1979). Resultatives discussed in this paper include these three types as subtypes. In each, there is a caused result reinterpreted metaphorically as a gradable property indicating a high degree.Footnote 4

Degree resultatives show a number of similarities with other types of intensifier expressions; they are quite common crosslinguistically and can be realized syntactically in various ways. In particular, English and Dutch degree resultatives follow several syntactic patterns. This syntactic variability suggests that emergence of second-order constructions is determined primarily not by the syntax but by the semantics. We point out two characteristics of the (literal) resultative constructions that license the (idiomatic) degree sense. Additionally, though English and Dutch are closely related languages, comparison of the two languages allows us to note subtleties of degree resultatives that might have gone unnoticed in a study of only one or the other of the languages. An examination of corpora from different time periods shows that the set of degree resultatives is rapidly expanding, due to the growing number of lexical items that can partake in the relevant constructions. The growth in the number of lexical items that can be interpreted as degree resultatives is analogous to the equally rapid growth in the number of lexical items that can be used as degree adverbs in Dutch in the period 1600–2000 (Hoeksema Reference Hoeksema2005). This is exactly what one might expect if the second-order construction is semantically motivated; language embraces multiple ways to express intensity. The study here, then, sheds light on how second-order constructions can arise, diversify, and thrive.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 2 offers an account of why and how the term degree is used in this paper. Section 3 discusses the necessity of a gradable interpretation in order for a resultative predicate to be used as a degree expression. Section 4 categorizes the English and Dutch constructions in which degree resultatives occur and offers an account of how certain literal resultative interpretations lend themselves to metaphorical degree interpretations. Section 5 traces the historical development of degree resultatives over a 200-year period in English and Dutch, noting the rise in number of types of constructions that can be interpreted as degree resultatives and in their frequency of use. Section 6 offers a semantic classification of the verbs that most frequently occur in degree resultatives. Section 7 notes other taboo or abusive terms that have yielded degree resultatives. Section 8 points out predictions of our account concerning DP versus PP complements of verbs. Section 9 is a conclusion.

2. Two Words of Caution on the Notion of Degree

Why we apply the term degree to the second-order constructions discussed here calls for explanation, since for many, that term has taken on a particular formal meaning.

We suggest that there are various ways to express degree. In the literature on degree marking, much attention goes to adverbs of degree, and the morphosyntactically marked categories of comparatives and superlatives (Corver Reference Corver1997, Neeleman et al. Reference Neeleman, Hans and Jenny2004).Footnote 5 Degree marking, however, is not just a matter of lexical heads. A broader view of the issue reveals important parallelisms between adverbs of degree and a number of other ways of expressing degree.

Suppose one wants to characterize Jones by ascribing to him a high degree of poverty. This could be done by using an adverb of degree: Jones is extremely poor, a stereotypical comparison: Jones is as poor as a church mouse, or a clause licensed by subordinating so that is read as a result of high degree: Jones is so poor that he has to send his children to the almshouse. One could also use pitch (and duration, see Braver et al. Reference Braver, Natalie, Shigeto, Adam and Michelle2016): Jones is póór, or repetition: Jones is poor, poor, poor. Some languages also use a variety of morphological processes, such as affixation, including diminutives and augmentatives: Italian basta e strabasta ‘it’s enough and it’s more than enough’, bello bellissimo ‘beautiful very beautiful’ (Dressler & Merlini Barbaresi Reference Dressler and Lavinia1994). Spoken languages tend to have a high number of lexical contrasts (morphologically unrelated lexical items) indicating degree: English eat versus devour. A variety of means of intensification litters the components of the grammar, much more so than means of de-intensification (Zillig Reference Zillig1982, Polanyi Reference Polanyi and Teun1985, Sandig Reference Sandig and Christine1991). Sign languages, in contrast, tend to indicate degree via changes in the phonological parameters (Wilcox & Shaffer Reference Wilcox, Barbara and William2006) or via a separate degree sign (Brito Reference Brito1984), although there are some lexical contrasts indicating degree, such as American Sign Language RAIN versus POUR.

There are also degree compounds (aka elative compounds), which are often comparison-based (German blitzschnell ‘lightning fast’) and may have a resultative meaning (Hoeksema Reference Hoeksema and Guido2012). Compare crystal-clear lit. ‘clear as crystal’, that is, ‘very clear’ with Dutch stervenskoud lit. ‘dying cold’, that is, ‘very cold’. In the latter, the interpretation does not seem to be ‘as cold as dying’, but ‘so cold, that it might cause death’. Similar cases in Dutch are kotsmisselijk ‘puke-nauseous’, snotverkouden lit. ‘snot suffering-from-a-cold’, that is, to have a cold to the degree that it causes one to produce (lots of) snot, stomdronken lit. ‘mute-drunk’, that is, drunk to the extent one cannot talk anymore. The same contrast can be found in Italian, where degree compounds such as mondo cane ‘dog world’, donna cannone ‘cannon woman/enormously fat woman’, for example, seem to be solely comparative, but stanco morto ‘dead tired’ hints at a resultative sense.

In the light of this rich variety of ways of expressing degree, the second-order constructions examined in this paper are insightfully analyzed as examples of degree expressions. Thus, we step away from a narrowly construed treatment in terms of DegP’s in favor of the older view (Sapir Reference Sapir1944, Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972) of gradability and degree marking as a pervasive property of natural language, expressible by a variety of mechanisms.

Further, degree expressions have varying interpretations, though the nuances play no part in our overall discussion. Intensity or high degree is a variable notion. In the case of a verb such as sweat (I am sweating my guts out), one thinks of the amount of sweat produced. The same holds, mutatis mutandis, for other verbs of emitting effluents (puke, piss, bleed) and verbs of ingestion (eat, drink, gorge). In other cases, such as fight or sing, high degree is more about intensity than amount produced. In yet other cases, duration may come into play, as with wait (Dutch zich suf wachten ‘wait oneself into a tizzy’). A verb like sleep (sleep one’s ass off) may be interpreted equally well in terms of duration and intensity (depth of sleep). In addition, we include cases such as Dutch de sterren van de hemel zingen lit. ‘sing the stars off heaven’, that is, sing beautifully, where the high degree interpretation is arguably associated with the manner of singing rather than raw intensity, as might be the case with, say, Janis sang her guts out every night. In general, in many cases it would be hard to decide whether one is talking about the manner or the intensity of the rendering. We, thus, do not explore these distinctions here, instead lumping them all together as intensification, since the degree expressed by the resultative is always high.

3. Degree Resultatives and the Importance of Endpoint

This paper looks at data from only English and Dutch. However, resultatives with varying syntactic structures occur in many spoken languages, including other Indo-European languages (French: Legendre Reference Legendre1997; German: Stiebels Reference Stiebels1998; Romanian: Farkas Reference Farkas2011, as well as genetically unrelated languages (Chinese: Sybesma Reference Sybesma1992, Cheng & Huang Reference Cheng, James Huang, Matthew and Ovid1995, Li Reference Li1995; Japanese: Washio Reference Washio1997, Nishiyama Reference Nishiyama1998; Korean: Kim Reference Kim, Susumu, Ik-Hwan, John, Joan, Young-Se and Young-Joo1993, Wechsler & Noh Reference Wechsler and Bokyung2001; Thai: Matsui Reference Matsui2007; Yoruba: Baker Reference Baker1989). None of these works mention degree resultatives, but it could be that the studies simply overlooked them, since their focus was elsewhere.

Sign languages also express resultatives in a number of ways (Loos Reference Loos2017). A motion event that ends in a particular way, for example, might well involve one or more classifiers, with the endpoint of the motion having a phonological change iconic of the result in one or more of the classifiers (see Tang & Yang Reference Tang and Gu2007, Kentner Reference Kentner2014). For example, to state that a car hit a tree and that the tree fell over as a result, the classifier for ‘car’ might move toward the classifier for ‘tree’, hit it, and then the classifier for ‘tree’ might change orientation from upright to being on its side. Similarly, to state that the car hit a tree and that the car rumpled, one might begin the same way, but when one classifier hits the other, the classifier for ‘car’, which uses the 3-handshape (![]() ), might bend the extended digits (

), might bend the extended digits (![]() ); if only the front of the car rumpled, the 3-handshape might bend only the extended index and middle fingers, and how tightly those fingers bend can indicate how great the rumpling was (Sutton-Spence & Napoli Reference Sutton-Spence and Donna2013). These resultatives can certainly be interpreted in an exaggerated and nonliteral sense, such as in a car hitting a tree so hard the tree flies up and flips a few times in the air before landing.

); if only the front of the car rumpled, the 3-handshape might bend only the extended index and middle fingers, and how tightly those fingers bend can indicate how great the rumpling was (Sutton-Spence & Napoli Reference Sutton-Spence and Donna2013). These resultatives can certainly be interpreted in an exaggerated and nonliteral sense, such as in a car hitting a tree so hard the tree flies up and flips a few times in the air before landing.

Sometimes these resultative degree interpretations can be encoded in single lexical items, such as the sign FALL-IN-LOVE in ASL, in which the dominant hand in a 1-handshape (like the classifier for person) literally falls on the palm of the nondominant hand and bounces along it. Several such signs appear in Irish Sign Language, including TONGUE-ROLL-OUT-OF-MOUTH to indicate so good one drools, STEAM-COME-OUT-OF-EARS to indicate intense anger, EYES-POP-OUT-OF-HEAD to indicate astonishment, and HAIRS-STAND-UP-ON-ARM to indicate getting the creeps (Leeson & Saeed Reference Leeson and John2012:134ff.). So far as we know, the first work to discuss this particular type of degree-resultative lexical items in sign languages was Wilcox et al. (Reference Wilcox, Phyllis and Maria2003:146), who said such items conveyed “deviant behavioural effect for intensity of experience” when talking about examples from ASL and Catalan Sign Language. In fact, even taboo degree resultatives occur in sign languages, as in ASL, such as NIPPLES-STIFFEN and BALLS-SHRINK to convey great cold, or GET-ERECTION to indicate attractiveness (Mirus et al. Reference Mirus, Jami and Donna2012).

Thus, our study may lead others to recognize degree resultatives in many languages, spoken and sign. Still, we predict that not all languages will have degree resultatives. Under our analysis, degree resultatives are second-order constructions that ride piggyback on ordinary resultatives (first-order constructions); they derive from ordinary resultatives and, therefore, cannot exist without them. Thus, if a language lacks literal resultatives, it will also lack intensifying degree resultatives, and if it has restrictions on literal resultatives, we expect those restrictions to hold for intensifying degree resultatives as well. The literature we have examined shows that this prediction holds cross-linguistically. That is, we have found no languages that have intensifying degree resultatives but no literal resultatives—an observation consistent with our claim that the former derive from the latter. However, we address an important complication regarding German in section 8.

Consider this prediction with respect to Italian. Italian exhibits a degree resultative exemplified in 6 with morire ‘die’ and impazzire ‘go crazy’—two of the exceedingly few secondary predicates allowed in this construction.

(6)

The examples in 6 have a number of properties in common with a Dutch degree resultative construction exemplified in 7 (Heinsius Reference Heinsius1929, Booij Reference Booij2010).

(7)

On the whole, however, Italian lacks the variety of degree resultatives found in English and Dutch. Certainly, resultatives with reflexives and NPs denoting body-parts found in English and Dutch do not have counterparts in Italian. Our analysis of degree resultatives attributes this to the fact that Italian, and Romance in general, is impoverished with respect to secondary resultative predicates. In Romance, most secondary resultative predicates can occur only with endpoint-oriented or accomplishment verbs (see Napoli Reference Napoli1992 for Italian; Farkas Reference Farkas2009 for Romanian). Thus, it is no accident that only a few second-order resultatives can be interpreted as degree resultatives. Modern Greek patterns much like Italian or Spanish with regard to these restrictions on secondary resultative predicates (Giannakidou & Merchant Reference Giannakidou, Jason and Amalia1999), and, like Italian, has a degree resultative with ‘to death’—a definite endpoint.

The notion of endpoint is an essential meaning component of secondary resultative predicates (under either literal or degree reading of the construction). However, in degree resultatives, what is important is not the endpoint itself, but the scale. Degree resultatives require gradable secondary predicates, which come in a variety of types (Kennedy & McNally Reference Kennedy and Louise2005). Some correspond to closed scales (with definite endpoints), some to open scales (without definite endpoints), and some to half-open scales (for example, the set of natural numbers ℕ form a half-open scale, with 1 as the definite endpoint at the lower end, but no upper endpoint). Depending on their scale type, different predicates combine with different modifiers (Klein Reference Klein1998, Paradis Reference Paradis2001, Rotstein & Winter Reference Rotstein and Yoad2004, Wechsler Reference Wechsler, Nomi and Tova2005). Closed-scale predicates easily combine with absolute modifiers (completely full, totally empty, absolutely dead), whereas open-scale predicates do not (*completely old, *totally large, *absolutely many), preferring nonabsolute modifiers (very, pretty, rather, quite).Footnote 6

This notion of absolute modifier is not to be confused with the notion of maximality. Note that an absolute modifier does not necessarily trigger the endpoint interpretation of the predicate. For example, half marks a point on a scale; combined with a modifier it can yield an absolute modifier that does not denote the endpoint of the scale, such as half-blind (as in She sits there so refined, and drinks herself half-blind, from Barry Manilow’s song “Copacabana”; the same is true for Dutch, as in 41 below).

The modifiers one finds most frequently with degree resultatives are of the absolute kind, even when the relevant predicate normally does not require an absolute modifier. For English, this point can be illustrated by the contrast between 8a,b, on the one hand, and 8b,c on the other.

(8)

Example 8a, with an absolute modifier, is entirely colloquial. Example 8b, with a nonabsolute modifier, sounds not entirely natural, perhaps self-conscious or humorous. We indicate this judgment here by #. However, 8c, with a nonabsolute modifier, is entirely ordinary. That is, the felicity of the type of modifier depends not on the predicate itself (silly), but on the construction.

In Dutch, this same effect can be found and more easily, since a larger group of adjectives are employed with frequency in degree resultatives. In fact, the effect is so strong in Dutch that we debated using an * to indicate the acceptability judgments in 9c and 10c, but opted instead for #, to be consistent with how we treated the English examples.Footnote 7

(9)

(10)

Thus, the fact that rot in 10c does not readily combine with erg ‘very’ is not due to the lexical preferences of rot—since that would predict 10d to be equally bad—but because it appears in a degree resultative. We conclude that the second-order construction itself imposes a scalar endpoint interpretation on the resultative predicate.

4. Classification of Construction Types

Today degree resultatives in English and Dutch occur in several syntactic patterns. We outline and exemplify them here, both for ease of reference in our later discussion of their emergence over time and in order to give a sense of the range of data behind the tables in that later discussion.

4.1. English

We outline six syntactic patterns of degree resultatives; then we summarize them in a table. The first syntactic pattern in English (type 1) is verb + fake reflexive + predicate. The meaning of the following types of verbs can be intensified by adding a reflexive pronoun and a resultative predicate: Intransitive verbs (such as laugh), optionally transitive verbs (such as eat), and verbs that can have a causative interpretation when used transitively (such as jump). The added resultative predicate provides a scalar endpoint. It typically has a negative connotation, denoting a state such a death, sickness, decay, etc., as in 2a above. This state, understood metaphorically, specifies an (end)point on a scale (as discussed in section 3). The resultative construction as a whole, however, does not necessarily have a negative connotation. For example, sick is a negatively evaluated state, but laughing oneself sick involves maximal mirth without adverse associations. In other cases, such as working oneself to death, there is a finer line between a literal interpretation and a merely intensifying interpretation. Still, one can say Every week, I work myself to death, and I love it. The modifier every week makes it clear that no literal reading is intended, while the second conjunct indicates a positive appraisal. Among the most common verbs that appear with this kind of intensification are laugh, dance, work, drink, and eat. The resultative predicate may be an AP (laugh oneself sick) or a PP (drink oneself to death). There may be restrictions on which verb combines with which predicate, as discussed in the next section.

The reflexive in this type of resultative construction is fake (Simpson Reference Simpson, Lori, Malka and Annie1983) because either the verb does not subcategorize for an object, or the object does not satisfy the verb’s usual selectional restrictions. For example, sing is usually intransitive, although it can take objects that are within its referential extension, such as a song or the national anthem. In particular, it does not generally allow an animate object, yet in sing oneself hoarse, the object is [+animate]. Fake reflexives cannot bear contrastive stress, a characteristic that helps in identifying them:

(11)

The second syntactic pattern in English (type 2) is verb + X’s body part + {off/out}. This construction also contains mostly intransitive or optionally transitive verbs. The NP that denotes the body part does not satisfy the verb’s selectional requirements; thus, it is not a genuine argument but rather a fake object (extending the use of the term fake reflexive). The verbs cry, freeze, fuck, laugh, scream, and work are commonly used in combinations such as freeze X’s extremities off, cry X’s eyes out, scream X’s head off, and work X’s tail off. Often the possessive pronoun is bound by the subject, as in 12, whereas other times, the possessive may be free, as in 13.

(12)

(13)

With verbs of communication (understood broadly enough to include sing) that take a goal/beneficiary argument, a free possessive pronoun is understood to be that argument.

(14)

When the possessives are bound, they require local antecedents just as fake reflexives do, as in 15a; they reject the use of own, as in 15b, as well as any form of contrastive stress, as in 15c.

(15)

The third syntactic pattern in English (type 3) is verb + [the + taboo term] + [out of NP]. This type of construction nearly always involves verbs that require a direct object. Examples include expletives, such as scare the hell out of someone, annoy the shit out of someone, beat the living crap out of someone, etc., as well as milder taboo terms that a parent, for example, might not be upset if a child used, such as those having to do with death or religion, including scare the living daylights out of someone, beat the devil out of someone. As noted earlier, however, while the expletive is the direct object of the verb, it is not an argument, nor does it satisfy the verb’s usual selectional restrictions. Thus, once again, one is dealing with a fake object. The argument—patient in this case—is the NP in the PP [out of NP].

Sometimes, this construction may contain a verb that usually does not take a direct object; instead, it takes a PP where the object of P is an argument of the verb. A blog post by Zimmer (2016) and Perek (Reference Perek2016) note relevant cases, such as 16, involving listen to, from COCA (Corpus of Contemporary American English). In 16, what would have been the object of to in the absence of a fake object (that is, your tape, as in listen to your tape) appears as the object of out of.Footnote 8

(16)

The fourth syntactic pattern in English (type 4) is verb + NP + predicate. Very often this is an ordinary transitive construction with a resultative secondary predicate added, as in love someone to death, bore someone stiff, scare somebody shitless. It has a passive counterpart (compare 17a–c with 17d–e, ungrammatical passive sentences corresponding to type 3).

(17)

Just as with English type 1, sometimes this construction contains an object that does not satisfy the selectional restrictions of the verb, and, in that sense, is fake; thus, the resultative predicate licenses a fake object. Furthermore, sometimes one finds verbs that can be understood as causative when they have an object (for example, work in They worked us too hard). In fact, the same range of verbs that allow a fake reflexive in English type 1 also appear in English type 4 with a fake object. Interestingly, even these English type 4 examples have passive counterparts, as shown in 18 (though sometimes the get-passive sounds distinctly better than the be-passive).

(18)

This raises the question of whether English type 1 really should be separated from English type 4. We demonstrate an advantage to maintaining this distinction when we turn to Dutch later. In the active sentences in 18, the syntactically complex structure (subject, primary verb, fake object, resultative predicate) gives rise to different interpretations of who is doing the action. In some instances, the subject is understood to have caused the object to do the primary action (as with 18a). In others, the subject is understood to have done the primary action plus caused the object to do that action (as with 18b). Still in others, the subject and object are both understood to have done the action, but the subject “out-does” the object (as with 18c, similar to She outdrank us). Finally, the subject can be understood to have done the action with a resultant negative effect on the object (as in 18d–e).

Also, just as with English type 3, sometimes this construction contains a verb that usually does not take a direct object, but, instead, takes a PP where the object of P is an argument of the verb. That argument winds up promoted to direct object position, as in 19.

(19)

The next syntactic pattern (type 5) is verb + NP + [out of X’s body part]. This is also an ordinary transitive construction with a resultative secondary predicate. NPs that denote body parts and associated concepts range over brain, wits, mind, skin, skull, etc., and the possessive must be bound by the experiencer argument of the verb, as shown in 20.

(20)

We distinguish English type 5 from English type 4 because its passive counterpart is more common than the active construction.

The next syntactic pattern (type 6) is verb + the {clothing/body part} + [off NP]. This construction has a transitive verb whose object denotes a piece of clothing or a body part, but that object is fake. The genuine argument of the verb—experiencer in this case—is the NP object of the preposition off ({charm/annoy/scare} the pants off somebody). An example from our corpora is provided in 21.

(21)

We show in section 6.4 that the examples with clothing differ from the examples with body parts in certain ways. Therefore, we talk about English type 6a, which concerns clothing, and English type 6b, which concerns body parts.

In table 1, we present the six types of degree resultatives we have characterized above.

Table 1. Six types of degree resultatives in English.

In sum, English presents six distinct constructions that degree resultative phrases occur in, where four of them contain a reflexive or body part/clothing bound by an argument of the verb. We consider this distribution in section 4.3 below.

4.2. Dutch

We outline four patterns of degree resultatives in Dutch, then summarize them in a table. However, before listing and exemplifying the types, we need to explain that Dutch word order generally places the finite verb in verb-second position and places other forms (perfect or passive participles, for example) at the end of the VP. For the sake of simplicity of exposition, we characterize our construction types in terms of the verb being at the end of the VP, since that is where the main verb will be if auxiliaries are used. Please keep that in mind when comparing the examples to the type pattern.

The first syntactic pattern in Dutch (type 1) is fake reflexive + predicate + verb. The examples in 22 contain fake reflexives with resultative predicates in a structure that looks identical to English type 1.

(22)

There is an important difference between the English and Dutch instances of type 1, however. The Dutch cases typically employ what is known as the short forms of the reflexive, for example, zich ‘him/her/itself’ rather than the long form zichzelf. This has to do with the fact that the reflexive is inherent in these constructions: The verb cannot take an object that is distinct in reference from the subject. Inherent reflexives in Dutch are generally short forms (but see discussion in Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, John and Jennifer2014). This is the reason why we did not conflate English type 1 with English type 4 in our discussion of English above; maintaining the distinction facilitates comparison of the two languages.

Dutch uses the short forms of inherent reflexives (Everaert Reference Everaert1986, Reinhart & Reuland Reference Reinhart and Eric1993, Bouma & Spenader Reference Bouma and Jennifer2008), but it appears that the complementary distribution of short and long reflexives described in the linguistic literature is showing signs of weakening. New usage of long reflexives is attested on the online social network Twitter, where they creep, albeit still rarely, into inherent-reflexive positions.Footnote 10 The long forms cannot be interpreted contrastively in their innovative use as fake reflexives, whereas they can be in their other uses. In 23a, a fake reflexive of Dutch type 1 appears in the nonstandard long form mezelf, where mezelf cannot bear contrastive stress (whereas dood ‘dead’ can, as indicated). In 23b, an ordinary transitive resultative of Dutch type 4 (discussed below and comparable to English type 4 discussed above) contains the expected long form mezelf, which can bear contrastive stress (as indicated).

(23)

The second syntactic pattern in Dutch (type 2) is (possessive) body part1 + [{uit ‘out’/op ‘on’} X’s body part2] + verb. In 24, Dutch examples of this construction have many similarities to the English construction of type 2. The direct object in Dutch, however, can denote either a body part (as in 24a, the eyes) or a sign of degradation or distress (that is, affliction) of a body part (as in 24d, the blisters). The object of the preposition (uit ‘out’ or op ‘on’) denotes another body part and is preceded by a possessive pronoun. However, only those direct objects that denote actual body parts can appear with an overt possessive (Cappelle Reference Cappelle2014). In 24a–c, the direct object appears without a possessive; the version with a possessive—comparable to English—is given in square brackets. Note that 24d–e involve affliction of a body part, hence there is no example with a possessive on the direct object.

(24)

If true body parts appear as both the direct object and object of the preposition, they must be semantically related: The first body part (the direct object) is typically a meronym of the second body part (the object of the preposition; we include lijf ‘body’ in 24c). That is, the first denotes a part of the second.

The idioms in 25 have variants in which the possessor is expressed by a short reflexive pronoun. In these instances, instead of the possessive pronoun, the object of the preposition (that is, body part2) appears with the definite article.Footnote 11

(25)

Perhaps this is because the possessive pronouns in examples such as 25 are locally bound by the subject. Indeed, local binding is required, as shown in 26.

(26)

The construction requires coreference, in one instance with a possessive and in the other with a reflexive. This is not uncommon; in many languages reflexives appear instead of possessives with inalienable objects (Herschensohn Reference Herschensohn, Christiane and Terrell1992, Postma Reference Postma, Hans, Pierre and Johan1997, Lødrup Reference Lødrup1999).

As expected and just like the English cases cited above, the possessive in examples such as 24 cannot be strengthened by eigen ‘own’, nor can it bear contrastive stress. Further, the reflexive in examples such as 25 cannot bear contrastive stress, nor can it be replaced with the long-form reflexive (but note the proviso mentioned above). Contrast 24a,b to 27a,b, and 25 to 27c.

(27)

The construction in 25, then, is ditransitive, where both objects (the reflexive zich and body part1 de longen ‘the lungs’) are fake. One might well want to categorize this construction as Dutch type 2b: reflexive + body part1 + [{uit/op} Def Art body part2] + verb.

Quite generally, Dutch type 2 (including Dutch type 2b) does not occur with verbs that usually link an argument to direct object position (genuinely transitive verbs); and all the direct objects in this construction discussed so far have been fake. Given that, one does not expect to find arguments in direct object position in Dutch type 2. However, a few verbs of communication are exceptional (such verbs appear in English type 2, but their behavior is different in Dutch). In 28a, the object of the preposition, Annie, is the goal argument of the communication verb praten ‘talk’. This verb occurs in a degree resultative in 28b, where the goal argument has been promoted to direct object of the verb. Given that body part1 is present as well (de oren ‘the ears’), 28b is a ditransitive construction, where the first object is an argument of the verb (the goal) and the second one is not. As in the ditransitive construction in 25, which has a reflexive, in 28b body part2 (het hoofd ‘the head’) is introduced by a definite article rather than a possessive; both body parts are understood to belong to Annie (the first object, still the goal argument of the verb).

(28)

Other communication verbs exhibit somewhat different behavior. Example 29a contains the verb vragen ‘ask’, which can occur with an argument in direct object position and another argument as the object of the preposition. Just as with praten above, the object of P is the goal argument. In 29b, vragen occurs in a degree resultative, but the goal argument has been promoted to direct object (as in 28b).

(29)

At this point we need to recognize the construction Dutch type 2c: NP + Def Art body part1 + [{van} Def Art body part2] + verb. Thus, Dutch type 2 has three instantiations, with two of them being ditransitives. We have analyzed them as instances of one type of construction for two reasons. First, there are two body parts in all of them, with the first one being a meronym of the second. Second, the body parts are understood to belong to an individual expressed as an argument of the verb. The three subtypes of Dutch type 2 can be conflated formally as follows: ({NP/reflexive}) + {(X’s)/Def Art} body part1 + [{uit/op/van} {X’s/ Def Art} body part2] + verb.

The next syntactic pattern in Dutch (type 3) is {fake reflexive/NP} + NP + verb. This construction is not a structural counterpart to English type 3. In fact, Dutch has no structural counterpart to English type 3 and English has no structural counterpart to Dutch Type 3. However, the Dutch and English type 3 constructions do have in common the fact that a taboo item often appears in both (such a term referring to a disease).

Dutch type 3 with a fake reflexive looks very much like Dutch type 1, especially given that the NP result is, arguably, a predicate (see remarks on a variety of NP predicate types in resultatives as well as copular and other constructions in Hoekstra & Mulder Reference Hoekstra and René1990, Fernández Leborans Reference Fernández, Ignacio and Violete1999:2359–2365, Müller Reference Müller2002, chapter 5, Bentley Reference Bentley, Andreas and Elisabeth2017). However, we argue that the construction with a fake reflexive and the one with a referential NP should be grouped together under type 3 for two reasons. First, when there is a fake reflexive in Dutch type 3, the phrase following it is always an NP that denotes an unpleasant result for the subject, such as a bump on the head, a horrible disease, or an accident. Consider the examples in 30.

(30)

In 30a, the audience is startled as though they have had an accident; in 30b, the subject we can be seen as left suffering from typhus; in 30c, Mies might end up giving herself a stroke. As in other degree resultatives, none of these result phrases are to be taken literally; they are meant to indicate high intensity. Thus, there is no possibility for a counterpart to any of the examples in 30 with a long reflexive form and/or contrastive stress that would receive a literal reading (that is, there are no sentences comparable to 23b).

A second reason to keep Dutch type 3 with a fake reflexive separate from Dutch type 1 is its resistance to being compositional semantically. At times the NP that co-occurs with the reflexive takes on a special meaning, making the construction an idiom (as in 31a). Other times the NP does not occur outside this particular construction type; that is, it is a “cranberry word” (see Trawiński et al. Reference Trawiński, Manfred, Frank, Lothar, Nicole, Stefan and Brigitte2008), for which a proper meaning is (nearly) impossible to give (as in 31b,c).

(31)

Nobody seems to know (including the main dictionaries of Dutch) what schompes or rambam mean, apart from the fact that they are assumed to be the names of imaginary diseases; startling oneself “a little hat” is not easy to explain either.Footnote 12

In some instances it seems that analogy with another expression lies at the source of examples like those in 31. To see what we mean, consider another example of an idiomatic intensifying degree resultative: zich een rotje schrikken lit. ‘oneself a firecracker startle’ = ‘startle heavily’. The word rotje ‘firecracker’ makes no literal sense in this context. However, there is a common idiom zich rot schrikken ‘startle oneself rotten’ and another common one zich een hoedje schrikken ‘startle oneself out of one’s mind’ (seen in 31a above). Zich een rotje schrikken may have emerged as a contamination of these two idioms.

In both examples in 30 and in more idiomatic ones as in 31, the NP is headed by the indefinite singular article een, except when the NP denotes a disease (or quasi-disease), in which case the article is singular and definite (het for neuter nouns; de for singular nouns, where masculine and feminine are conflated).

One also finds degree resultatives that fit the pattern of Dutch type 3 but with a fully referential NP instead of a fake reflexive. This NP is an ordinary direct object of the verb, receiving a theta-role, as in 32. We analyze the constructions in 32 as examples of Dutch type 3 because the second NP within the VP still indicates an unpleasant result for the subject within the same range of unpleasant results. Unlike 32a,b, the example in 32c contains not a disease name but a taboo term, de moeder ‘the mother’, a recent innovation in informal Dutch. It is not in our Delpher data, but attested on the Internet from 2010 onward.

(32)

The next syntactic pattern in Dutch (type 4) is NP + predicate + verb. This type is very much like English type 4, as seen in 33.

(33)

The examples in 33 have verbs of contact-by-impact (just like the Dutch type 3 examples in 32). The particular examples in 33 were chosen specifically to illustrate a degree reading. For other combinations of predicate + verb, such as kapot slaan lit. ‘kaput hit’, there is ambiguity between a literal reading of ‘hit something causing it to become broken’ and a degree reading of ‘hit something hard’. Both English and Dutch make copious use of contact-by-impact verbs in type 4 constructions.

The object in examples such as 33 is an argument of the verb, and the sentences are grammatical with or without the degree resultative. However, just as happens with English type 4, there are some Dutch verbs that generally do not take an object; yet, in combination with a resultative predicate, an object is licensed, so an object can occur in Dutch type 4 (compare English examples in 18). The resultative predicate in such instances can be a simple particle (such as uit ‘out’) or a degree resultative phrase. The examples in 34 contain schelden ‘swear, call names, scold’, which does not take a direct object except when it cooccurs with a resultative phrase.

(34)

The Dutch construction does differ in some ways from the English one, however. For example, English freely uses many psych verbs in type 4 (as in annoy someone to death), but Dutch has limitations on psych verbs. Consider the verb ergeren ‘annoy’. This verb can be used as a simple transitive, as in 35a, where the experiencer is the direct object. However, unlike in English, a degree resultative phrase cannot be added, as shown in 35b.

(35)

Alternatively, ergeren can be used with a fake reflexive (the short form only, which cannot receive contrastive stress), where the experiencer is the subject and the entity causing the annoyance is the object of P, as in 36.

(36)

To this structure, a degree resultative phrase can be added, so in contrast to 35b, 37a is grammatical, again with the idiom groen en geel. Example 37b, which is ambiguous between a degree and literal reading, is grammatical as well.

(37)

Here {groen en geel/ dood} is predicated of the fake reflexive and thus, per force, of the subject. Thus, the structures in 36 and 37 can be seen as a variant of type 4. We refer to the first one as Dutch type 4a and to this one as Dutch type 4b: fake reflexive + predicate + [P + NP] + verb.

For the vast majority of speakers, psych verbs such as shockeren ‘shock’, storen ‘bother, disturb’, irriteren ‘irritate’ are acceptable only in simple transitive constructions (as in 35), so they do not show up at all in degree resultatives. However, irriteren is used like ergeren ‘annoy’ in 36 by a growing group of speakers, although prescriptivists still frown upon this. For us, the interesting point is that those speakers who can substitute irriteert ‘irritates’ for ergeren in 36, can also do this in 37. In table 2, we present the four types of Dutch degree resultative constructions we have characterized above.

Table 2. Four types of degree resultatives in Dutch.

In sum, Dutch presents four distinct constructions that degree resultative phrases occur in, where only one variant of one type (type 4a) does not contain a reflexive or body part/clothing bound by an argument of the verb. We consider this distribution in section 4.3 below.

4.3. Generalizations

Three generalizations emerge from the English and Dutch data with respect to transitivity, argument structure and grammatical functions, and body anchoring. Those generalizations lead us to a conclusion about the origin of the second-order resultative constructions.

To begin, we examine transitivity. All degree resultative phrases occur in a clause with a direct object, whether that direct object is genuine or fake. We attribute this requirement to the the first-order construction—the original literal resultative predicate. That is, nearly all sentences with secondary resultative predicates have a direct object. An exception is seen in 38a, but it has a transitive counterpart, seen in 38b.Footnote 13

(38)

Other exceptions include verb + particle combinations such as {Piss/Fuck/Bugger off!}, where an ordinarily telic interpretation can reasonably be called resultative (Cappelle Reference Cappelle, Marja and Sinikka2007).

The next generalization concerns argument structure and grammatical functions. A particular interplay between argument structure and grammatical expression is a characteristic feature of degree resultatives. All degree resultatives have a direct object. However, in most types of degree resultative constructions the direct object is not licensed by the verb. Furthermore, if the object is licensed, it does not always satisfy the verb’s selectional restrictions outside the resultative construction; the only exceptions are English type 5 and Dutch type 4a.

Further, some types of degree resultatives tend to involve only one argument of the verb, which appears as subject; the fake reflexive in English type 1 and Dutch types 1 and 3 is bound by that subject, as is the possessive within the body part NP in English type 2 (for those examples in which the possessive is bound) and Dutch type 2a. Note that the possessive in Dutch type 2a occurs with the object of a preposition, but due to the relationship of meronymy between the two terms referring to body parts, the possessive relation extends to the body part denoted by the direct object. Dutch Type 2b has both a fake reflexive and a body part NP; the reflexive, which is bound by the subject, is interpreted as a possessive to the body part. Thus, the monovalent nature of these verbs shines through despite the presence of a direct object.

Additionally, sometimes arguments of the verb are linked to atypical grammatical functions. For example, in English types 3 and 6 the argument that is usually linked to direct object position appears, instead, in object of P position, while the NP that appears in direct object position is not an argument but rather an indicator of degree. Furthermore, in Dutch type 2c, a goal argument of a verb of communication that usually appears as the object of P appears in direct object position. Finally, in English types 2, 3, and 4, an oblique argument that is usually the object of P can appear as a possessive or as the object of a different P. In sum, degree resultatives in English and Dutch do not conform to ordinary patterns in linking arguments to grammatical functions. However, the relationship between argument structure and grammatical expression plays out differently in each language.

The final generalization concerns body anchoring. Degree resultatives are semantically “anchored” to the body of the affected argument. That argument may be repeated as a fake reflexive or it may be obligatorily coreferenced with a possessive (English types 1, 5; Dutch types 1, 2b, 3, 4b). Many degree resultatives explicitly mention body parts (English types 2, 5, and 6b). English type 6a treats clothing items as inalienable as body parts (Gordon Reference Gordon1986, Chappell & McGregor Reference Chappell and William1996).Footnote 14 The taboo terms found in English type 3 can be viewed as referring to internal, inalienable body parts (in that they will always belong to the affected argument, even if they are physically separated). This is clear for bodily effluents (kick the shit out of NP), but it is also true for the frequent expletive hell (knock the hell out of NP), where one still feels the historical effects of an exorcism (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Donna2008). Likewise, in Dutch type 3, illnesses such as tuberculosis are internal to the body, and even fictional/imaginary/nonexistent conditions such as schompes and rambam are perceived as inalienable. The secondary predicates used as intensifiers in English types 1 and 4 tend to denote properties of the body (to pieces, stiff, sick) or of the mind (silly, numb). Silly, for example, in a sentence like I’ll slap you silly, conveys senselessness, a state of being unable to think. However, these predicates never denote more controllable or behavioral properties (such as rich, good, sweet, polygamous). The same wholeness is observed in Dutch type 3, where the second NP of the ditransitive is all-encompassing: an accident, typhus, a stroke—never something incidental such as a hangnail or a stubbed toe. Diseases seem like very different entities from body parts. However, some recent discussions of inalienable possession have stressed that this category extends beyond body parts, to properties of mind and body, such as happiness and health (see, among others, Rooryck Reference Rooryck2017).

Based on these generalizations, we offer an account for the emergence of second-order readings of literal resultatives. When a result is extreme in that it hits an absolute endpoint plus it has a holistic effect on the entity it is predicated of, a degree interpretation becomes available simply by virtue of that literal meaning. That is, since the literal meaning is extreme in appropriate contexts, it can be used as a hyperbole in other contexts that are close to appropriate, and, eventually, it can be used entirely metaphorically in any context. Body anchoring is the key here: It assures such a holistic effect and thus predisposes the construction toward allowing a degree reading to emerge.

Further, the play between argument structure and grammatical functions typical of these constructions also contributes to the likelihood of a second-order reading. Here the literal reading can range from odd to truly bizarre to impossible. How does one annoy pants, for example, or charm socks or sing lungs? Thus, when faced with annoying pants off a person, one scrambles to see the pants as a relevant extension of the person and, thus, seeks a reading in which, say, the person is so very annoyed, she starts shedding clothing (perhaps because she is shaking so hard?). The metaphorical reading itself predisposes one toward a degree interpretation. One can certainly find resultatives under a literal interpretation with objects that are fake, as in 39a, and even with objects that are fake reflexives, as in 39b.

(39)

However, the very creativity of using fake objects and fake reflexives pulls one to the margins of what the grammar will allow, forcing speakers to interpret language creatively. This is now the realm of the nonliteral, and that gives one license to associate other readings with a given construction.

5. Historical Developments

We conducted a diachronic study of resultatives used for intensification—that is, degree resultatives—in English and Dutch based on the data from over the past 200 years. For English, we used the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA, Davies Reference Davies, Irén and Alexandra2012).Footnote 15 For Dutch, we used Delpher. Both online corpora allow one to search by decade. For COHA, the decades run from 1810 to 2010; for Delpher, we restricted ourselves to the period 1810–1995 (Delpher includes materials only up until 1995, so for the last decade, the 1990s, our data represent only a half-decade). The COHA data are roughly the same in size for all decades (on average 20 million words per decade) with the exception of the first two decades, the 1810s and 1820s, which are 1.2 million and 6.9 million, respectively. The Delpher data are more lopsided, with significantly less data from the decades between 1810 and 1890 compared to the decades after 1890, and a steep decline in the 1940s and 1950s. However, our claims in this paper concern very robust trends that are affected only marginally by the varying amount of data from decade to decade. For example, the 1930s material consists of 3,151 tokens, whereas the 1940s material of only 1,509 tokens (the drop is due to paper shortages during the war and in the postwar period). Yet the number of predicate types is 45 in each decade.

We did a systematic search for all secondary predicates that we either knew or hypothesized to be involved in degree resultatives (such as to death, limp, and so on). In COHA, we searched for all verbs that combine with the predicate in question (using lemma-search). In Delpher, unfortunately, no such option was available. Instead, we had to do the search for verbs by hand.Footnote 16 Delpher is considerably larger than COHA. This is reflected in the fact that we found 4,962 instances (tokens) of degree resultatives in COHA and 28,359 in Delpher. Nonetheless, we found somewhat more variety in predicate types in the English data.

We searched for occurrences of each predicate since 1810, isolated the ones that were resultative predicates, and then made judgments as to whether the constructions each predicate occurred in were open to a degree resultative interpretation. Not all combinations of a resultative predicate and a verb necessarily have a degree reading even when they fit one of the construction types outlined in section 4. For example, while dood ‘dead’ is a common predicate in Dutch degree resultatives today and historically, there are many combinations that we view as regular (literal) resultatives, including doodschieten ‘shoot dead’, doodhongeren ‘hunger/starve to death’, doodvriezen ‘freeze to death’. In contrast, for zich doodlachen ‘laugh oneself to death’, intensification is the most likely reading.

In some cases, it is not easy to tell hyperbole apart from literal interpretation without help from the context. For instance, zich kromwerken ‘work oneself bent’ will most likely be a hyperbole when said of a young man who is working hard at his job in advertising; it will be literal when said of an old farm hand who has done hard physical labor most of his life. An expression such as zich ongans eten ‘eat oneself nauseous’ might be used to describe a situation in which so much food was eaten that the eater vomited, but it can also be used to indicate simply that a lot was eaten. In some instances, there was not enough information to tell us whether we had a literal or degree reading. In such instances, the primary criterion we used for interpreting a construction as a degree resultative was the presence of an implication of extreme intensity or amount. Anyone approaching this kind of issue will have to make similar judgment calls.

We divided the two centuries into 4 periods of 50 years for comparison. We see considerable growth in the number of predicate types, less so in the number of tokens per million words. In COHA, the latter show fairly random swings in the 19th century, ranging from to 9.2 tokens per million words in the 1810s to 3 tokens per million words in the 1840s. On average, we found 7 tokens per million words in the 19th century data, after which that number slowly crept up to 17 per million in the 1990s.

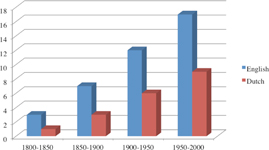

Strikingly, the diachronic corpora show that new, emerging predicates do not replace old ones, but supplement them. Basically, the later the period, the more predicates one finds. Further, once a predicate appeared, it kept reappearing. Thus, we witness (near) monotonic growth in the number of predicates that occur in degree resultatives. This is true for both English and Dutch.

For example, the English resultative construction laugh oneself sick was first attested in 1773 (according to the Oxford English Dictionary). Since that time, it had to compete with many newer idioms (laugh one’s head off, laugh oneself limp, laugh oneself into a tizzy, laugh one’s socks off, laugh one’s booty off, and so on), and yet there are no signs of it becoming obsolete. Only a few expressions have disappeared and those were rare to start with; we cite worry pallid, in 40.

(40)

Other expressions persisted or evolved into a slight variant, as with beat {hell/tarnation} out of X, which is currently adorned with a definite article: beat the {hell/tarnation} out of X (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Donna2008).

With respect to Dutch, degree resultatives are first attested around 1600, that is, a few decades before they are attested in English (as far as we have been able to establish). Presumably, they are somewhat older than the first printed attestations, but it is difficult to say how much older. Similar to our findings for English, we found few cases that became defunct, as in 41, which is from the 1920s.

(41)

Note that the use of half mal in 41 confirms our earlier claim that what is important in degree resultatives is the availability of a scale, not the endpoint (or a sense of maximality) itself (see discussion in section 3).

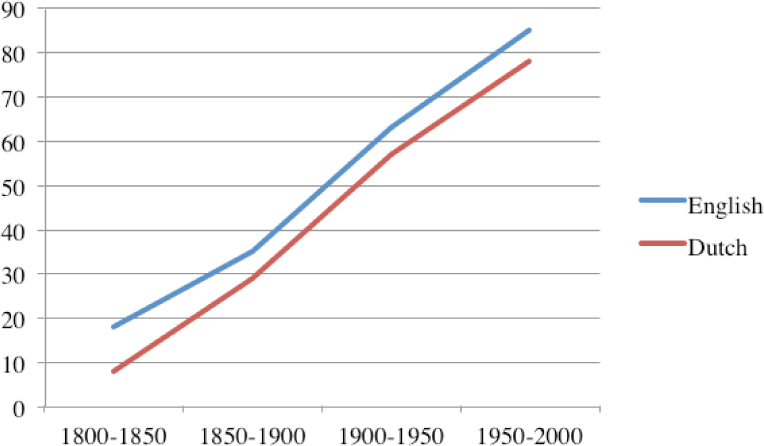

In listing the secondary resultative predicates in the figures below, we include the predicate itself along with any material in the degree resultative that is not the verb, a fake reflexive, or an argument of the verb. In other words, for examples with laugh X’s head off and laugh oneself silly, we list head off and silly as secondary predicates. Thus, we do not count head(s) off in her head off, his head off, and our heads off as three different secondary predicates; instead, we only count lexically distinct predicates. In figure 1 below, we chart the number of secondary predicates appearing in degree resultatives in English and Dutch for each 50-year period.

Figure 1. Number of lexically distinct secondary predicates in English and Dutch degree resultatives.

In part, the consistent increase in the number of lexical items that serve as secondary predicates in degree resultatives is due to the continuous rise of expletive constructions—both in English and in Dutch—over the time span in figure 1 (Hoeksema & Napoli Reference Hoeksema and Donna2008). For example, shitless is a relatively recent addition (1950’s), probably based on earlier, nontaboo, witless, in combinations such as The attack scared us shitless. As time passed, the number of new nontaboo secondary predicates in degree resultatives, such as out of his/her skull, also continuously rose. The oldest attestation of a degree resultative with this secondary predicate was found in a movie script from 1968 (although more literal examples are attested earlier).

(42)

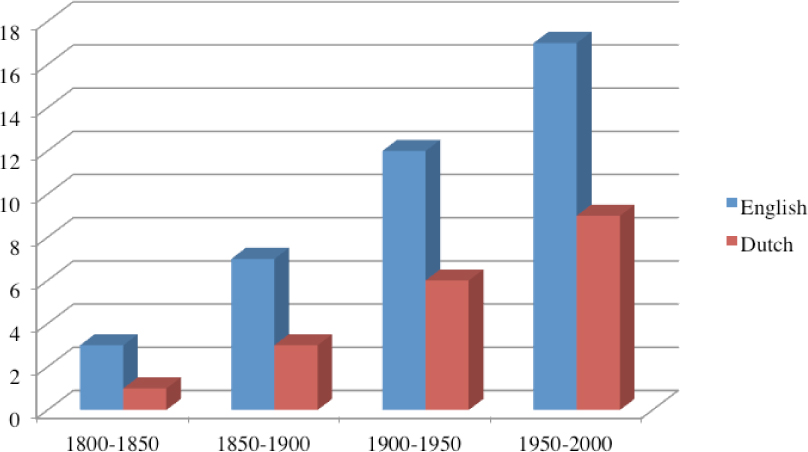

Many other body-part idioms are also fairly new. The English body-part/clothing off construction (Cappelle Reference Cappelle2014, see also section 6.4 below) grows from 0 in the first half of the 19th century to 3 in the second half of that century to 7 in the first half of the 20th century and to 12 in the second half of that century. If we include in our count variations due to extra adjectives, that number would be even higher (for example, worry one’s pretty little head off, work one’s damn ass off). In figure 2, we show the increasing number of idioms that express body part removal in intensifying constructions in the two languages.

Figure 2. Number of different types of intensifier constructions in English and Dutch that express body part removal.

However, not all types of degree resultatives increase in token frequency throughout the two centuries we are considering. One of the more prominent constructions is type 1 in English and type 4 in Dutch: the predicates to death/dood, which peak around 1900 in English (a little later in Dutch) and then decline a bit (presumably as a result of new competitors stepping in, as suggested in Gyselinck & Colleman Reference Gyselinck and Timothy2016b). In figure 3, we show the number of new combinations verb + to death/dood per half century.

Figure 3. New combinations verb + intensifier to death/dood per half century.

Dutch appears to follow English at a distance. In the first half of the 19th century, we found no clear cases of intensifier uses of dood in our Dutch material. However, the large scientific dictionary of Dutch, Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (WNT; entry “dood”), mentions four degree resultatives attested from the 17th century onward, for example, zich doodschamen lit. ‘to shame oneself dead’, that is, to be ashamed to death’. Dutch resultatives with dood peak about 1930, and then slowly decline. Hoeksema (Reference Hoeksema and Guido2012) notes a similar decline for dood as a modifier in Dutch elative compounds (doodeenvoudig ‘dead simple’, doodeng ‘dead scary’) in the second half of the 20th century. Gysselinck & Colleman (Reference Gyselinck and Timothy2016b), likewise, found a decline in productivity of Dutch dood-resultatives, using different measures (such as the number of unique verb + intensifier combinations divided by number of tokens).Footnote 17 This decline seems to be in lockstep with the developments in English and may well represent a much wider trend among intensifier constructions in the (western) European Sprachbund (see Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath, Martin, Ekkehard, Wulf and Wolfgang2001, Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Tania2006); we leave that larger issue to subsequent research. Below we note further similarities between English and Dutch, pointing toward English influence on Dutch.

One area where English and Dutch degree resultatives differ considerably is the use of reflexives. Fake reflexives occur in both languages, but Dutch uses them to a much greater extent than English. Our English data have between 8% (1980s) and 18% (1880s) cases with fake reflexives. In Dutch, their number varies from 52% (1880s) and 80% (1940s). The preponderance of fake reflexives in Dutch may be related to the fact that Dutch has many inherently reflexive verbs, that is, verbs whose reflexive object is not an argument (for example, zich schamen ‘be ashamed’, zich generen ‘be embarrassed’, zich ergeren ‘be annoyed’, zich vervelen ‘be bored’), in contrast to English, which has relatively few inherently reflexive verbs, such as perjure oneself and pride oneself, but very little else. Thus, when Dutch employs fake reflexives in degree resultatives, it is availing itself of the already much-used option of having nonargument reflexive objects. Moreover, we should point out that the inherently reflexive Dutch verbs listed above are among the most common verbs to be found with degree resultatives.

6. Verb + Secondary Predicate Collocations in Degree Resultatives

The variety of combinations of verbs and secondary predicates in degree resultatives has been increasing slowly but steadily over the past four hundred years in both English and Dutch. This growth can be viewed as evidence of the productivity of the various constructions that degree resultative predicates can occur in (Cappelle Reference Cappelle2014, Perek Reference Perek2016). Certain verbs or semantically-based groups of verbs occur with an ever-growing assortment of secondary predicates, and certain secondary predicates occur with an ever-growing assortment of verbs. A closer look reveals that verbs that welcome degree resultatives fall into semantic groups; an examination of frequently occurring verb groups and secondary predicates offers a greater understanding of why degree resultatives are best viewed as second-order constructions.

For example, Margerie (Reference Margerie2011), in a discussion of the very common secondary predicate to death, notes that it originated in a literal resultative (as in starve the peasants to death); but, quite early on, in the 17th century, a degree resultative usage emerged, and even what Margerie calls a degree modifier usage (as in her modern example I am sick to death of Star Wars quotes). Middle-period degree resultative usage of this predicate involves frequent combinations with negative psychological verbs, including bore, frighten, scare, annoy, and hate. Combinations with positive verbs—as in love somebody to death, nowadays fairly common—are not attested in our corpora before 1950. Thus, one can see a development over time of the secondary predicate to death from a strictly literal reading (with verbs such as starve) to a degree reading based on a metaphor (with main predicates such as sick in the sense of “annoyed”) to a reading that is (nearly) exclusively degree (with verbs such as love). This progression shows that by 1950, the degree interpretation of resultatives becomes so firmly established that it casts aside literalness and no longer even relies on metaphor; the second-order reading is solid. Below we present details on three of the most frequently used verb groups and the secondary predicates they collocate with, and on two of the most frequently used secondary predicates and the verbs they collocate with.

6.1. Work-Related Verbs

There are many work-related verbs, and there are several secondary predicates that appear with them in degree resultatives. Consider first occurrences of work itself, as in work one’s fingers to the bone or work one’s tail off. While both mean working hard, the former mainly concerns labor involving the hands, such as cleaning, scrubbing, typing, knitting, sewing. A quarterback training hard may be said to be working his tail off, but not to be working his fingers to the bone. This observation is reflected in the set of verbs associated with one’s fingers to the bone and one’s tail off (we restrict ourselves to clear degree resultatives, and ignore ones that might be more (nearly) literal in drastic situations, such as I’ll cut your tail off if I ever see you near my daughter again). Note that for both these secondary predicates, work is the most frequent verb on the list of collocates given in table 3. In fact, the two sets are very similar, with one exception: freeze is also relatively common with one’s tail off, but not with one’s fingers to the bone. We come back to the verb freeze in the next subsection.

Table 3. Verbs collocating with tail off, fingers to the bone, and vingers blauw.

The resultative play {his/her} fingers to the bone can describe playing guitar or some other instrument in which the fingers are the only crucial articulator (for example, guitar or piano rather than bassoon or trumpet) but not, for example, team sports, as in #The Sixers played their fingers to the bone, or frolicking children, as in #We let the kids at our daycare play their fingers to the bone. That is, while a degree resultative using one’s fingers to the bone clearly relies on metaphor, the literal meaning of the secondary predicate still lingers.

Note that the senses of play that do not combine with one’s fingers to the bone are perfectly acceptable with other types of resultative predicates, as in The Sixers were playing their tails off or The kids at the daycare were playing their hearts out. These data show that degree resultatives are sensitive to polysemy. Still other uses of play are illustrated in 43.

(43)

Dutch has an idiom involving fingers, zijn vingers blauw ‘one’s fingers blue’, which may be used for intensifying purposes. Like its English counterpart, it is used with verbs involving hand actions, albeit a different set of verbs. In particular, verbs of writing and counting (typically counting money, involving manipulation of coins or bills) are involved (we leave out a lot of verbs that appear less frequently with vingers blauw). The examples with werken ‘work’ are less common, and they sound less idiomatic to our ears. All but one of the 10 examples are from serialized novels or news articles translated from English. We suspect that the originals had the idiom fingers to the bone, for which vingers blauw is the best Dutch approximation. In table 3 and the following tables, # indicates number of instances found in the data.

In general, work frequently shows up in degree resultatives, and not just with the two English secondary predicates examined in table 3. In our English corpora, it ranks as the third most frequent verb, behind beat and scare. In our Dutch corpora, werken ‘work’ comes fifth.

What is striking about the two English secondary predicates in table 3 is their strong connection to the most basic sense of work (‘expend effort’). Other secondary predicates exhibit a weaker connection to that basic sense. Consider, for example, our data for one’s ass off. Table 4 shows that not only are there more verbs that collocate with this secondary predicate, but the semantic range of those verbs is greater as well, including laugh and related verbs, such as smile and grin; verbs such as lie and perjure, and a few verbs that typically take an object, such as bore or sue. The more taboo secondary predicate (with ass) is more productive than the less taboo one (with tail) in degree resultatives, which is expected given the prevalence of taboo terms in degree resultatives in general. In a few cases, the verb is transitive and the possessive pronoun is not coreferential with the subject (as in He will sue your ass off).

Table 4. English verbs collocating with one’s ass off.

In Dutch, the predicates that most often collocate with werken ‘work’ are uit de naad ‘out of the stitch’ and het schompes (see our comments below 31 regarding this item, which has no apparent independent meaning), as shown in table 5. Other verbs typically denote work-related activities (or sports, which may be either a hobby or a job).

Table 5. Dutch verbs collocating with uit de naad and zich het schompes.

Perhaps the prominence of lopen ‘walk’ and rennen ‘run’ on this list might seem odd, but only until one examines the context. A typical example is given in 44.

(44)

It turns out that the verbs lopen ‘walk’ and rennen ‘run’ in such examples either denote sport-related running or are used in the sense of work, not locomotion.

6.2. Freeze One’s Extremities Off

A statement such as I am freezing is ambiguous between a reading where a person is in the process of turning into ice and a more common reading where the person feels exceedingly cold. The latter reading presumably originally derived from the former as a hyperbole. Nowadays, it is no longer felt to be a hyperbole, hence the need to reinforce it with a degree resultative construction, usually involving body extremities, as shown in table 6 below. This need for an added degree resultative construction may be strengthened somewhat by the fact that ordinary boosters for freeze seem to be in use only for the literal ‘turning into ice’ reading of the verb. Consider the examples in 45.

(45)

In table 6, we list the nouns in our corpora that fill the X position in freeze one’s X off in degree resultatives only. The nouns listed were found in COHA, but the Internet is replete with examples that involve references to just about any bodily extremity in combination with to freeze off.

Table 6. Nouns that fill the X position in freeze one’s X off.

The fact that degree resultatives with freeze involve extremities follows from the fact that these may, in fact, literally freeze off occasionally (from frostbite). However, the body parts that most easily freeze, such as ears, toes, or corneas, are not the most popular in the hyperbolic use. Rather, there is a clear preference for taboo terms and mock taboo terms (euphemisms) for more polite conversation (assets, extremities), which are more generally used for intensification (see Napoli & Hoeksema Reference Napoli and Jack2009), and hence less likely to be misunderstood in the more literal sense of limbs freezing off. Indeed, the body parts extend to cases where actual freezing off is less likely, such as freezing one’s ass off.

The Dutch cognate of English freeze is vriezen. The literal ‘turn into ice’ interpretation may be intensified by a resultative CP; thus, it is not among the types found in table 2 (which are limited to secondary predicates).

(46)

In other words, ‘it freezes so hard that it produces cracks’ (or creaky noises). Unlike English freeze, vriezen cannot be used to describe animate beings that are extremely cold, which may well be why the Dutch verb does not occur in degree resultatives. Footnote 19 In contrast, the cognate verb frieren in German is much more like English freeze; it can be used with animate subjects to indicate extreme cold, and, accordingly, degree resultatives occur commonly with this verb, particularly taboo-related ones, as shown in 47.Footnote 20

(47)

With regard to English, then, we note that just as in the case of fingers to the bone combined with work-related and other verbs (see subsection 6.1), the choice of secondary predicates occurring with freeze in degree resultatives is neither completely arbitrary (otherwise one might also expect #I am freezing my heart out or #I am freezing my lips off), nor is it completely motivated by probability in real life.

6.3. Head-Related Activities

A common predicate in degree resultatives is one’s head off, which occurs with a range of verbs (though not freeze), as seen in table 7. Again, we focus on degree readings only, so the many cases of chopping, tearing, blowing, cutting, lopping, knocking, or ripping someone’s head off in our corpora are not included.Footnote 21

Table 7. Verbs collocating with one’s head off.