Introduction

Political, social, economic and demographic changes in developed welfare states have led to concerns about rising demands for services, particularly support services for older and disabled people (Pierson, Reference Pierson2001). On the “demand” side, increased longevity, reduced morbidity and political pressure from citizens and disabled and older people needing long-term care has led to a growing realization amongst policy makers and practitioners that present service levels, particularly in health and long-term services, are inadequately funded and failing to respond effectively and efficiently to people’s needs (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2005). On the “supply” side, falling birth rates and changes in family structures, as well as neo-liberal changes to welfare provision which have stressed the importance of activation policies (eg. welfare-to-work programmes for women, lone parents, disabled people and the long-term unemployed), and changing relations and expectations within families and communities have meant that there are falling numbers of unpaid and family carers available and there have been substantial changes to the welfare mix of contributions from the family, the state, the market and wider civic society (Evers, Pijl, & Ungerson, Reference Evers, Pijl and Ungerson1994).

Care policy is an example of a social and structural issue that has profound effects on outcomes than can either exacerbate or reduce gender inequalities. Although this is changing, the evidence suggests that in developed welfare states, women bear the double burden of being responsible for childcare and/or providing care and support for disabled and older family members, and taking part in paid employment (Hervey & Shaw, Reference Hervey and Shaw1998). This contributes to the gender gap in both public life, where women are substantially less likely than men to occupy senior positions in work, politics and civic society, and private life, where women are significantly more likely than men to be at risk of poverty and to bear the effects of economic pressures and welfare restructuring. The evidence suggests that care policy (both in terms of childcare, and long-term care) in some types of welfare regimes achieves better outcomes than others (in terms of delivering equality, particularly, gender equality) (Walby, Reference Walby2004).

Developed welfare states have responded to the challenge of how to manage welfare and long-term care policies in such a way which caps the rising demand for resources, leading to a shifting of responsibilities across public sectors (eg. from health to social care and from national to localized provision), and across sectors (eg. from state to private or third sector provision, or from state to family [or, indeed, family to state]) (Moffat et al., Reference Moffat, Higgs, Rummery and Rees Jones2012). At the same time, a variety of international, national and local political, social and economic factors have led to changes in the governance of welfare, including increasing commodification of services and deprofessionalization of practitioners (Newman, Reference Newman2005). Rising demand for support and services has also come not only from demographic changes, but also from increasingly politicized “user” movements (such a disability rights organizations in the UK and the Netherlands, and older people’s organizations in the United States) who have rejected both family and informal care as exploitative (for both carers and cared-for) and state care as increasingly fragmented, unresponsive and dehumanizing – indeed, rejecting the rhetoric of “care” altogether and demanding social rights, empowerment and control over the type and level of support received instead (Morris, Reference Morris2004). Increasing regulation of services in response to “consumer” demand has only partially succeeded in responding effectively to these changes: new models of service delivery are being actively sought in response to these complex political, social and economic changes (Ungerson & Yeandle, Reference Ungerson and Yeandle2007). However, any rise in the reliance on families to provide long-term care inevitably means that the burden of this will fall disproportionately on women, leading to widening gender inequality: particularly, if the provision of such care is unpaid or not compensated by the state.

There are commonly two different approaches to defining gender equality. One takes a “sameness” approach: in other words, it presumes that gender equality happens when women are the same as men. The other takes the more complex “equity” or “fairness” approach advocated by Fraser (Reference Fraser1997).

The first approach is taken by many supra-national bodies such as the United Nations (UN) and European Union – eg. the European Employment Strategy gives specific guidance on targets to address the gender pay gap and to increase rates of women’s employment to match that of men, despite the fact that many member states have distinct histories and ways of framing the gendered division of labour between paid and unpaid work. Gender equality in this approach means that men are the “unit of assessment,” and that gender equality is achieved when women are approaching equality with the male norm.

This approach is problematic in several ways. It assumes that the standard that men have set is unproblematic. Using men as the norm ignores the social and economic advantages enjoyed by a society that overvalues their paid work in comparison to that of women (we pay plumbers in the UK £12.17 compared to child carers an average of £6ph – does this mean we value our plumbing twice as much as our children?). It also ignores the overrepresentation of women in unpaid work (such as childcare and long-term care) which means they are not able to participate full-time in the labour market. Factors such as these lead to occupational segregation, which is partially responsible for the fact that the gender pay gap is in the UK is still around 75 per cent 45 years after the Equal Pay Act. Even the most conservative estimates put the economic cost of women’s under participation in the labour market at around £23bn lost revenue per annum (RBS).

It also ignores the fact that whilst the market may not recompense women adequately for the unpaid care work they undertake, that does not mean that this work is unvalued by society. Indeed, one approach to equality advocates that there should be more equitable sharing of paid and unpaid work across the genders, rather than trying to recompense carers which has the result of reinforcing gendered divisions of labour.

These debates within feminism are commonly referred to as the “equality versus difference” debate: do we try to make women equal to men, or do we try to accept that they are different and try to change the way in which they are valued? This is not an easy problem to solve. Fraser (Reference Fraser1997) and others have advocated using the idea of “equity” (fairness) rather than “equality,” and recognizing that this is a complex idea.

For Fraser, gender equity should take neither the route of making women equal to men, nor compensating them for undertaking care, but find a way of achieving seven principles:

1. anti-poverty;

2. anti-exploitation;

3. income equality;

4. leisure time equality;

5. equality of respect;

6. anti-marginalization; and

7. anti-androcentralization.

Fraser proposes that women’s, instead of men’s, current life-patterns should become the “norm” expected, so that people spend less time in the marketized labour force, and devote more time to other kinds of labour such as care, activism, and civic and political participation (Fraser, Reference Fraser1997, p. 48), a model she calls the “universal caregiver model” of society.

However, whilst Fraser’s concern with equity between the genders is valid, it does not necessarily follow that such a model is either universally desired or achievable within contemporary welfare states. Platenga et al. (Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009) contend that Fraser’s vision is not that practical or quantifiable, but nevertheless contains the useful idea that the equal distribution of paid and unpaid work is not enough for equality. They use the idea of gender equality as being one which encompasses an equal sharing of assets such as paid work, money, decision-making power and time (Platenga et al., Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009, p. 22), which they operationalize to use comparatively by developing the European Gender Equality Index. The author maintains that both Fraser’s and Plantenga’s (2010) theoretical framings can be usefully operationalized in policy analysis to measure gender equality outcomes, and this is the primary purpose of this paper.

At the time of fieldwork, the UK scored roughly midway on Platenga et al.’s European Gender Equality Index. In governance terms for long-term care policy, local authorities are responsible for providing long-term care for disabled and older adults, and for providing services to support informal carers. Local authorities are also responsible, therefore, for setting eligibility criteria for accessing services. Normatively, there is an expectation that families will be the default providers of long-term care with the state only stepping in if the family is absent or unable to provide care. Recent policy changes have seen the development and extension of personalization in services, where eligible individuals receive a nominated sum of money to purchase their own services in lieu of receiving support directly from statutory care providers. This is referred to in various ways (direct payments, personalization and other schemes varying by local authority in England and Wales, self-directed support in Scotland). Payments cannot normally be given to family carers, although family carers providing full-time care can receive their own Carers Allowance (currently, set lower than unemployment benefits or minimum wage) separately and are relieved of the obligation to seek paid employment that is a feature of income-replace unemployment benefits.

In policy terms, this means there has been no deviation from the underlying principles and drivers of community care legislation set in the early 1990s in the UK: the marketization of services, the targeting of services on those most at risk, and the normative assumption that the family is responsible for providing care and support (Mason, Tetley, & Urqhuart, Reference Mason, Tetley, Urqhuart, Beech, Hand, Mulhern and Weston2006). Moreover, whilst there has been recognition of the role that childcare policy plays in tackling gender inequality, there is little emphasis in policy on the role that could potentially be played by long-term care policy. This is in stark contrast with welfare regimes that have been more successful at tackling gendered inequalities, who have explicitly recognized and attempted to tackle the structural inequalities caused by a reliance on family care in BOTH childcare and long-term care (Pascall, Reference Pascall, Maltby, Kennett and Rummery2008; Pascall & Lewis, Reference Pascall and Lewis2004; Walby, Reference Walby2004).

Care policy has been used to critique the standard Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Adersen1990) way of modelling welfare regimes based largely on cash transfers and decommodification which ignored women’s caring labour, or used the option of women not having to provide caring labour for free (Knijn & Kremer, Reference Knijn and Kremer1997). However, to date, this modelling and analysis been largely deductive, looking at overall policies rather than inductively examining their governance and gender equality outcomes. Care policy is also a site of conflicting normative, theoretical and empirical tensions (Rummery & Fine, Reference Rummery and Fine2012): eg. policy drivers which pull towards employment for women, disabled people and older workers are in conflict with drivers which place the emphasis for the provision of care and support for children and adults on the family. However, the role that the governance of care policy plays in achieving egalitarian outcomes is not yet well documented or understood. This paper is intended to further that understanding. The author attempts to answer the following questions:

Question 1: What case studies of long-term care policy are there in developed welfare states that lead to good gender equality outcomes?

Question 2: Using inductive methods based on policy analysis, rather than deductively sampling for existing welfare typologies, can we develop new models of long-term care policy?

Question 3: How valid and reliable are these models, and which governance features lead to the gender equality outcomes?

Question 4: How context-specific in terms of welfare pluralism and mixed economies of welfare are the features of the models, particularly with regards to the different roles of the state, communities, families and people needing long-term care (Evers & Stetlik, Reference Evers and Svetlik1993).

Methods

A mixed methods iterative approach to gathering and analysing the data was used to achieve the study’s aims.

Aim 1: to find suitable case studies to examine in depth

Using academic search engines and snowballing of grey literature, case study countries and federal/sub-federal regions with the following characteristics were sought:

1. Good gender equality outcomes – measured using an adapted version of the European Gender Equality Index (Platenga et al., Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009) with the UK as the baseline.

2. Developed welfare states.

3. Similar “dependency ratios” (ie. percentage of employable workforce to children/older/disabled people needing care and support) to the UK.

4. A high degree of formal (state) involvement in long-term care.

5. A variety of governance and constitutional arrangements to reflect the possibilities open to the UK (eg. different roles for the state, market, communities and individuals; different roles for central versus local government; different roles for state versus sub-state/federal agencies)

Over 250 published articles and grey literature were read, and grouped using Qualitative Comparative Analysis methods (Hewitt-Taylor, 2001). The case studies chosen as a result of this process were: Denmark, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Aim 2: to develop models of long-term care policy

Further inductive analysis of the themes in the empirical and published evidence from the chosen case studies was carried out. This resulted in the findings being synthesized into two models which internally shared dominant, relevant characteristics and contrasted sharply on external factors. Further analysis revealed which characteristics were non-context specific. This finally produced two models from which it was possible to describe simple, common elements, rather than a complex descriptive account of many case studies. The different models are referred to as:

1. The Universal Model (Denmark, Iceland and Sweden).

2. The Partnership Model (Germany and the Netherlands).

Aim 3: to check validity and reliability of findings, and context-specificty of models

1. An Advisory Group of international and UK academics, and policy makers and stakeholders in the Scottish, Welsh and UK governments was appointed.

2. Several workshops, focus groups and seminars at different stages of the project were held with different kinds of stakeholders (policy makers, practitioners, nonstatutory and academics) to help develop and test the findings and models. N = 5 (overall groups =6 including that held at Stage 4 below).

3. Interim findings were presented to different international academic conferences to check their theoretical and empirical validity and reliability.

4. Academic Country Experts were appointed to write country reports on the countries and regions chosen for our case studies (Hantrais, Reference Hantrais1999).

5. The Country Experts were invited to present their case studies directly to the Advisory Group and other stakeholders during a workshop/focus group to respond to queries from them.

6. Semi-structured interviews with a range of stakeholders (academics, policy makers, practitioners and nonstatutory organizations) were carried out at the interim stage (when choosing our case studies) and during the final analysis (when testing our findings) (N = 25). These comprised of civil servants working in the Scottish Government on long-term care, nonstatutory civic organizations concerned with gender equality, and carers and long-term care, elected politicians and activists with a particular interest in gender equality and/or long-term care, trade unionists, civil servants in the Welsh Assembly, academics) and nonstatutory stakeholders outside of Scotland. Interviews were transcribed, inductively thematically analysed using NVIVO and the validity of the findings checked through a series of events and discussions with stakeholders who had not taken part in the interviews.

Aim 4: to establish which long-term care model was “best” for gender equality and noncontext specificity

The analysis then used what was found about welfare pluralism and the mixed economy of welfare (Evers & Stetlik, Reference Evers and Svetlik1993) and applied theories of historical institutionalism (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999) to establish which elements of the models were context specific and which could be easily transferred into other contexts (Dolowitz & Marsh, Reference Dolowitz and Marsh1995).

Finally, Fraser’s (Reference Fraser1997) framework of the seven principles which should underpin progress towards a “universal caregiver” model of society (anti-poverty; anti- exploitation; income equality; leisure time equality; equality of respect; anti-marginalization; and anti-androcentralization) was operationalized and used to grade each long-term care model on a 5-point scale for progress.

Findings and discussion

The result of the analysis indicated that the cases studies could be grouped into two models of long-term care policy: the Universal Model and the Partnership Model. The key features of each model are described below, and then discussed with relation to the role that individuals, the state, families and the market play in providing long-term care (Evers & Stetlik, Reference Evers and Svetlik1993), the gendered outcomes in terms of advantages and drawbacks (Fraser, Reference Fraser1997), and which features were not judged to be context specific.

The Universal Model

The Nordic states are commonly held up as an example of universal state provision of services leading to high levels of gender equality. This is slightly misleading: there is no one “Nordic” model of welfare, and even those states with high levels of state control over welfare and long-term care services have introduced forms of market and individual involvement in the provision of services. Comparative social policy experts have always questioned whether there really is one “Nordic” model of welfare, and whether the difference between that and other models is as marked as is often claimed (Mahon et al., Reference Mahon, Anttonen, Bergqvist, Brennan and Hobson2012). Although, for the purposes of this project, we were not using welfare state typology as a sampling frame, it is notable that all the “Nordic” states met our sampling criteria of having good gender equality outcomes and state involvement in the funding and/or provision long-term care services. The three case study examples discussed here all share common features that make them examples of “good practice” in this field: they all have gender equality at the heart of their constitutional framework and policy values, score highly on the Gender Equality Index, have high levels of state involvement in the provision of (or commissioning of) childcare and long-term care services and adopt a universal “social rights” approach to the provision of services (Table 1).

Table 1. Universal model characteristics.

a Based on Platenga et al. (Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009), using EU/OECD data. European Gender Equality Index.

Countries that fell into this model had normative policy frameworks that were heavily focussed on gender equality. Aspirations towards gender equality informed the constitutions of the countries, and also underpinned the development of welfare services. All of the case studies fall into the “social democratic/Nordic” welfare model (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Adersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen2009). This means they provide public services on a universal basis, without stigma or loss of status. The twin commitment to gender equality and universality means that long-term care services have always been part of state provision.

For this reason, three countries in this group were chosen, who form the Universal Model: Denmark, Iceland and Sweden.

Denmark

Around one in six of older people receive home care services in Denmark, which is provided free of charge. Recent changes include a reablement assessment and service before people are eligible for home care, and a very small direct payments scheme. Informal care is used but always considered to be supplemental to formal care.

As with all the countries in this model, Denmark scores relatively well on all gender equality indices. It works with a dual earner–carer model, whereby the assumption is that both paid work and unpaid care are equally shared between the genders, but this is more successful in long-term than in childcare policy: most parental leave is used by mothers, contributing in part to a gender pay gap of around 16 per cent. Denmark and Iceland are commonly seen as the most “marketized” or “neo-liberal” of the Universal Model countries, although the commitment to gender equality and universal social services remains strong.

Iceland

Until the early 1980s, most state care for older and disabled people was provided through institutional care (ie. residential and nursing homes), but since 1982, policy changes have led to the development of home care services which are provided by municipalities (local government). User fees are charged for the nonhealth parts of the services – these vary but are modest (and income-related), so only 9.4 per cent of the total expenditure on home care services comes from these fees. Unpaid care by relatives plays a significant part in the provision of help and support for older people (Siguroardottir & Kårehol Reference Siguroardottir and Kårehol2014) with very small numbers receiving a working-age carer’s allowance. The main caregiver is usually a spouse (roughly gender equal) but in 27 per cent of cases, this informal care is provided daughters (Siguroardottir et al., Reference Sigurðardóttir, Sundström, Malmberg and Ernsth Bravell2012).

Iceland has one of the lower gender equality scores of the Universal Model countries, in part because of the segregated nature of the labour market, the “care gap” of unpaid leave taken by mothers, and the reliance on unpaid care from daughters. The gender pay gap is 18 per cent – slightly higher than the EU average – but still significantly lower than the UK. Moreover, indices which combine different elements of gender equality consistently put Iceland at or near the top of the league tables (European Commission, 2013).

Sweden

Gender equality policy, since the 1970s, has focussed on improving women’s access to work as paid carers (around 20 per cent of employed women work in publically financed childcare and long-term care).

However, 14 per cent of older people use home help services, and there has been a shift since the 1980s away from institutional towards home based services. At the same time, there has been a rise in daughters – particularly low-income daughters – providing unpaid care for their parents: higher income families are more able to pay for home based and institutional care.

Sweden has had a sustained policy focus on gender equality since the 1970s with the result that it scores highest amongst our Universal Model case studies on all the gender equality indices apart from equal sharing of leisure time. This is probably because it relies on mothers to provide at least 75 per cent of the childcare of younger children, and on lower-income women to provide unpaid care to disabled and older relatives.

Governance in the Universal Model of Long-Term Care Policy: the responsibilities of the state, the market, communities, families and individuals

The state plays the biggest role in the Universal Model of all the models under discussion. It is the primary funder and provider of services at both a national and local level. Most services are funded through a mix of national and local taxation. The state also plays a significant role in the provision of training and quality assurance for workers and services, which offers protection to both those who provide and use the services. High levels of state involvement mean that the costs and risks of funding and providing services are shared equally across the population, whilst the benefits are also felt equally by all regardless of income.

The market plays a reduced role in the Universal Model, but it is not absent altogether. Higher income parents and users of long-term care services are able to purchase additional help and services from a limited range of for-profit providers. There is some private sector involvement in the provision of long-term care services which are funded or commissioned by the state. There is also a limited “internal market” of providers being developed whereby state providers are encouraged to use marketized means to compete for contracts to improve the quality of provision, and a limited use of direct payments/cash-for care/long-term care services to enable individuals to exercise more choice in service provision. These are not popular: take up of direct payments is low, and marketization, particularly in long-term care, is met with discontent from both providers and service users – and there is no evidence that it substantially reduces costs or improves quality (Eydal & Rostgaard, Reference Eydal, Rostgaard, Gislason and Eydal2011).

The community does play an informal role in providing and supporting childcare and long-term care, as it always has, but there is very little development of nonstatutory civic sector providers or user-controlled services. It is not the case that where the state is heavily involved in the provision of services that civic involvement in the community is underdeveloped: levels of volunteering, civic organization and individual participation in civic society organizations is as high if not higher in social democratic/Nordic countries as it is in other types of political and welfare regime (Immerfall & Therborn, Reference Immerfall and Therborn2010). However, community organizations are less involved in the direct provision of core long-term care services and more in the provision of additional, special interest groups – eg. self-help and self-care groups, sports and leisure groups, and training and advocacy.

Families tend to see themselves as working in partnership with the state, or as the providers of low-level help and support, rather than the main providers of long-term care. There is some involvement of unpaid carers in inter-generational care of older parents, particularly in Iceland and Sweden, and this is gendered, with the burden falling disproportionately on daughters (particularly low-income daughters).

The primary responsibility for individuals in the Universal Model is to take part in paid labour and share in the burden of paying, through taxation, for the provision of universal long-term care services. Services are universally available (although contributory fees are tailored to reflect income levels) and so there is no perceived difference between those paying for and receiving the service: everyone pays into the pot, and everyone benefits (even those without children will benefit eventually from the provision of long-term care as they grow older). However, there are gendered expectations on individual women to provide some kinds of care: to be at home with young children, and to provide unpaid care for older parents (Table 2).

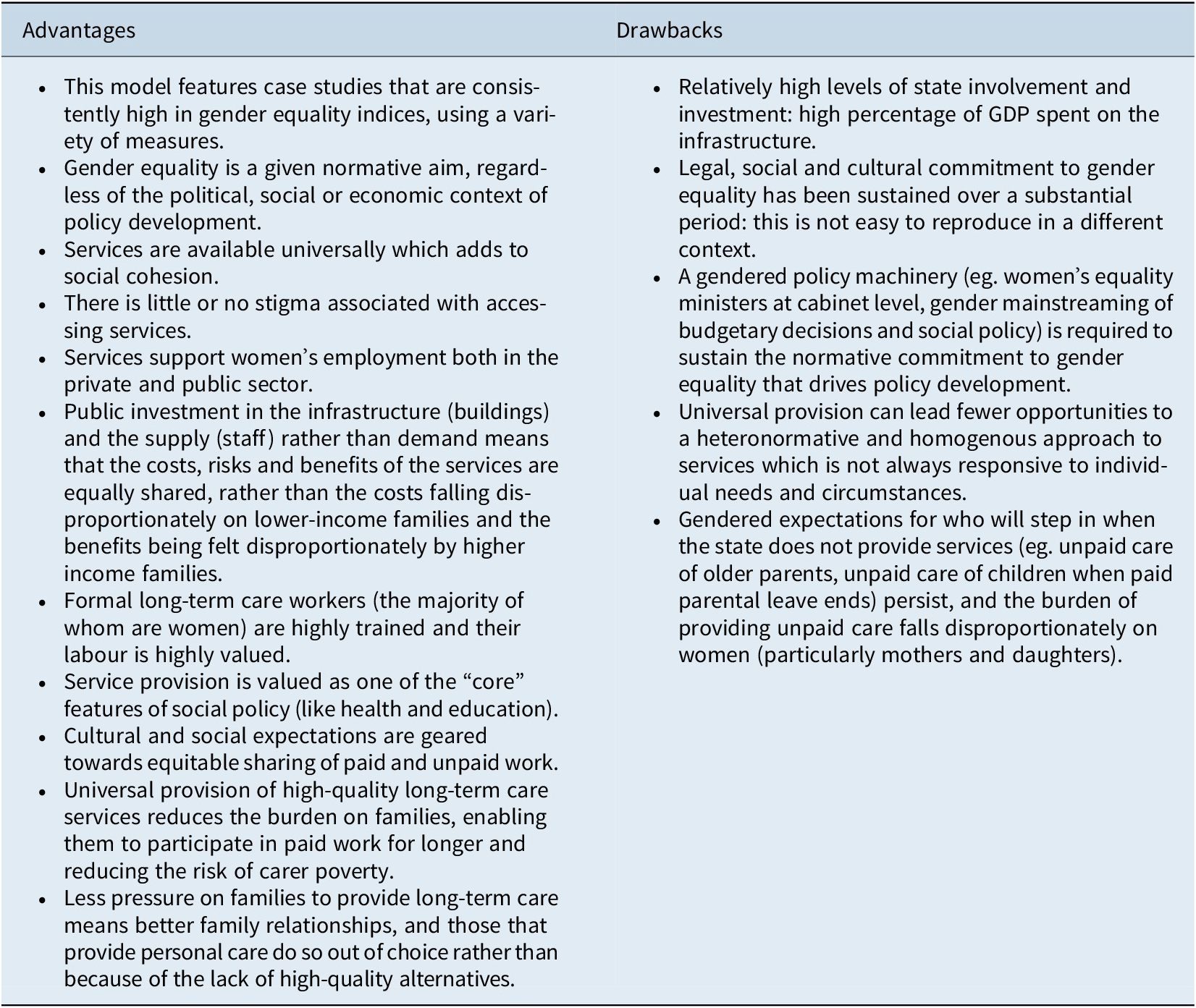

Table 2. Gendered outcomes: advantages and drawbacks of the Universal Model.

Key lessons and non context-specific features of the Universal Model

1. All of the case study countries in the Universal Model have gender equality enshrined into their legislative and policy-making structures. Where countries have formal written constitutions, gender equality is one of the key values that underpin the aspirations of those constitutions. However, a written constitution is not the only place where a commitment to gender equality can be evidenced: key statutes and common laws can provide a similar level of commitment, particularly when backed up by gendered policy machinery to implement and police gender equality. Equalities ministers at Cabinet level in both the UK and devolved parliaments would be possible, as would a commitment to gender mainstreaming in budgetary processes, public commitment to European and UN objectives on gender equality, and power given to existing bodies such as human rights commissions to hold both national and local government to account for the provision of services which support gender equality.

2. The Universal Model provides universal, not targeted services. This is crucial in tackling not only gender inequality, but also inequality over the life course between those who work and those who are unable to work due to age (either being too young or too old) or impairment, illness and disability. Higher levels of workforce participation amongst women, particularly low-income women addresses the poverty experienced by older women as a result of underemployment over the life course. Greater social cohesion and social solidarity results in societies that are more egalitarian and less divided. Long-term care services are treated in the same way as the National Health Services (NHS) and education in the UK: as core parts of a universal, fair welfare state, with clear sharing of risks and benefits.

3. Care, and thus women’s work, is valued in the Universal Model. Formal carers are relatively highly skilled and well paid, there is investment in their skills and training, and they are a highly valued and respected sector of the workforce. Although these jobs remain highly gendered, (particularly unpaid care of older parents), the fact that care services are universally available and staff are respected means that women’s labour, both paid and unpaid, is valued.

4. Policies join up to be most effective. The Universal Model works effectively to support gender equality because it tackles it on many levels.

5. There is reduced financial pressure on women to undertake high levels of unpaid long-term care due to the lack of tax incentives or support for unpaid carers coupled with universal provision of high-quality long-term care. Moreover, investment in the provision long-term care means there are many jobs available for women that are highly valued and support their long-term career development.

The Partnership Model

Countries that fell into the Partnership Model saw gender equality as an important policy driver, but it was not necessarily the main, or even most important, factor underpinning the development of long-term care policies. They had developed welfare states, but did not view the state as being necessarily the only or main provider of services. The state was seen more as a driver of policy: setting a legislative framework and in some cases providing funding and services, but doing so in partnership with the market, with communities and families, and with individuals. There was a greater role played by municipal authorities than in the Universal Model, and thus sometimes a greater variation in the availability and quality of services. However, the state did play a strong regulatory role, and individuals did have important rights to access services (Table 3).

Table 3. Partnership model characteristics.

a Based on Platenga et al. (Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009), using EU/OECD data.

The provision of long-term care has always been seen as the responsibility of the state to a certain extent in the Partnership Model, and the Netherlands, in particular, has seen relatively high spending in this area. Social rights to long-term care provided by municipalities has been a feature of this model since the mid-1980s, but in both of our case study countries underwent substantial revision in the 1990s and again in recent years, reflecting the growing demand for these services from an ageing population. In long-term care, the state is seen as having an important role, but not being the sole provider of services and support. Instead, support is seen as being funded and delivered in a partnership between the state, employers, the community, families and individuals.

Policy in the Partnership Model has the effect of recognizing and valuing women’s labour as family carers. It creates incentives for women, particularly low-income women, to provide care and rewards them for doing so: no family carer is left without an income because she is providing care and support. However, this is at the cost of women’s labour market participation and equality in the public sphere, and there is little incentive towards a more equitable sharing of care labour across genders.

Germany

The most significant recent change to long-term care policy occurred with the introduction of long-term care insurance. This is a national scheme that offers benefits based on three levels of need with fixed lump-sum benefits, along with cash payments for carers which can be supplemented by means-tested benefits. The purpose is to enable those who need care and support to purchase their own services from a mix of formal and family carers, using insurance-based state benefits topped up either through their own means or additional benefits.

Unlike countries in the Universal Model, Germany has opted to support women’s care labour in long-term care by reimbursing them through cash payments, rather than encouraging women into the labour market and providing universal formal long-term care services. Although cash benefits to recompense family carers were heralded as supporting and valuing care work undertaken by women, they have been criticized for leading to greater gender inequality, particularly amongst low-paid, low-skilled women for whom the cash benefits incentivise remaining away from the formal labour market for longer periods. Moreover, higher income women are more likely to make use of formal publically funded care services creating further social division. However, this does mean that higher skilled women are less likely to take long career breaks meaning that employers are likely to benefit from their re-entry into the workforce, and income inequality across the genders in higher income families is reduced. Lower-income women are more likely to have a financial incentive to provide care to family members because they can receive payments through the long-term care insurance scheme and through cash benefits directed at them.

The Netherlands

Long-term care in the Netherlands has recently undergone substantial change, separating out those with medically-related chronic health problems (who are entitled to care within a health funded institution) from those with less severe needs (who are now eligible for support to help them stay in their own homes and participate in society). This is coupled with a reduction in eligibility for direct payments for disabled people, which enabled those living at home to employ their own carers (including family members). These changes are part of an ongoing policy drive to reduce costs by moving responsibility for the provision of long-term care from the public to the private purse (Grootegoed & van Dijk, Reference Grootegoed and van Dijk2012).

Governance of long-term care policy in the Partnership model: the responsibilities of the state, the market, communities, families and individuals

In the Partnership Model, the state acts more as a commissioner than a direct provider of services. It provides a regulatory framework for the quality of the delivery of long-term care, including regulating who can provide the care and how payments to individuals to purchase care can be spent. It also plays some role in directly providing services at both national and municipal level. However, services are not simply provided through taxation, as in the Universal Model, but through a combination of taxation, insurance, employer and employee contributions. Compared to the Universal Model, there is a greater role for local and municipal authorities in this model, both in directly providing services and regulating the quality of local market provision. However, eligibility for services and the level of cash benefits is set nationally, not locally, which provides an equitable and uniform level of subsidy regardless of location.

The market plays a significant role in providing formal care services in long-term care. Recent changes to long-term care policy in both Germany and the Netherlands have been specifically designed to allow greater choice for service users and to involve the market in the direct provision of services where appropriate. This is ostensibly a gender-neutral policy move: users are meant to be free to combine formal and informal care provided by the state, the market and family in ways which best meet their needs and circumstances, and in theory this could be from equal numbers of men and women in both the formal and informal sphere. However, we know that women are hugely overrepresented as carers in both formal and informal long-term care. The reality of a large reliance on the market to provide care effectively means a continuing reliance on the paid and unpaid labour of women and does not address gender inequality in the provision of care. Moreover, it creates a two-tier care system between higher income women who can afford to supplement formal care through the market, and return to and remain in the labour market, and lower-income women, who cannot afford to supplement insufficient formal provision other than through their own labour, and thus are more likely to work part-time or withdraw from the labour market, increasing their risk of poverty.

Communities also play a more significant role in providing services and support in the Partnership Model than in the Universal Model. Often, the civic society organizations are drawn into the market of providing formal services, and there is sometimes a great reliance on informal social networks to provide low levels of support (eg. befriending services, housework and monitoring). Families, particularly women, who do not have access to these social networks are at a disadvantage in this model, as they are more likely to have to fill in the gaps themselves or to have to pay for formal support. However, social networks and social capital can be strengthened by community involvement in the provision of care, with carers who might otherwise be isolated building and sustaining emotional as well as functional support networks.

Families are perhaps the most important partner in the Partnership Model, and it relies heavily on collaboration between individuals and wider families (particularly children in the case of long-term care) to take the responsibility both for providing care and support, and for arranging, co-ordinating and integrating with the formal delivery of services. Reliance on “family” care usually hides the fact that such care is usually (but not always) provided by women. Cultural preferences for daughters over sons, coupled with a lack of family leave or other incentives to make increased participation in care work attractive financially to men, mean that care work remains gendered.

The responsibilities of individuals in the Partnership Model are first to participate in the paid labour market and contribute to the tax and insurance base, which funds the formal provision of services. Second, individuals have a great responsibility to provide some or most of care themselves: in the low-level support of disabled and older relatives, and in the co-ordination (and sometimes provision) of higher-level long-term care. The state acts more as a broker of support in partnership with individuals than a direct provider in this model (Table 4).

Table 4. Gendered outcomes: advantages and drawbacks of the Partnership Model.

Key lessons and non contextspecific policy features of the Partnership model of long-term care

1. Providing cash benefits directly to service users is fairly simple to do. In fact, cash benefits, tax credits and child care benefits already form a significant part of social policy provision in most developed welfare states, including the UK.

2. This model could easily be adapted for different governance, legislative and political contexts. Federal and devolved government and municipalities can develop their own versions if they have sufficient tax raising and social policy powers. A strong centralized social democratic state is not needed to deliver this model, and it can adapt to different political and ideological priorities.

3. Long-term care insurance is widely seen as one of the most important tools in preparing for the growing demand for services in developed welfare states. Present systems of taxation and/or asset-based funding, or increasing reliance on unpaid informal care, are not tenable and will not deal with the growing crisis in long-term care funding and provision.

Comparing the models for gender equity and context specificity

What are the ideas, institutions, and actors that make the Universal Model work? (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999)

Two main ideologies underpin the Universal Model. The first is that of social citizenship that involves the universal sharing of welfare risks and benefits through state mechanisms. Long-term care services are seen as a crucial part of the “cradle to grave” coverage of the welfare state, just as education and health care provision are. Services are largely provided directly by the state, although some market and individualized mechanisms for service provision are being introduced in this model. Services are funded through local and national tax contributions. They are not targeted (other than a relatively generous dependency threshold) or means-tested. This commitment to the idea of universalism also engenders a sense of national solidarity: all citizens work, and all citizens grow old, so all citizens contribute to, and benefit from, the provision of long-term care services. This is also key in that women are not expected to provided long-term care for free – they have the choice NOT to care (Knijn & Kremer, Reference Knijn and Kremer1997)

The second main ideology supporting the Universal Model is that of gender equality. Article 65 of the Icelandic Constitution guarantees equal treatment before the law and basic human rights regardless of gender. Equal citizenship in the Danish Constitution extends to the right to work, the right to vote, to access education and the right to state assistance to all citizens. These are enshrined in equal opportunities legislation since 1920, alongside major welfare reforms that underpinned the current welfare state. These reforms were heavily influenced by the “first wave” of the Danish feminist movement from 1900 to 1920. The Swedish Constitution is predicated on equality between women and men a fundamental constitutional norm and an explicit policy objective. In the Universal Model, women and gender equality issues were part of the legislature relatively early, and norms of gender equality informed constitutional arrangements and the foundations of the welfare state broadly. Nevertheless, the sharing of public political power is lower on the Gender Equality Index for countries in this model than on other indices: Iceland is at 0.65, Denmark at 0.52 and Sweden at 0.7. However, this still compares favourably with the UK at 0.46.

The institutions that make the Universal Model work are directly linked to the ideologies that underpin the model. The first is the nature of the welfare state itself. In all three case study examples (Denmark, Iceland and Sweden), the foundations and institutions to deliver comprehensive welfare state services were developed alongside nation-building and constitutional framing of citizenship rights. Although Iceland has the oldest Parliamentary democracy in the world, the revision of its constitution and the foundation of its welfare state took place in the early part of the twentieth century, and both processes were informed by a strong women’s movement. Recent re-working of the Icelandic constitution in the post-2008 economic crisis has taken the opportunity to reiterate the shared nature of the nation’s resources, its commitment to gender equality and its commitment to a comprehensive welfare state. Denmark and Sweden similarly laid the institutional basis for both their universal political, civic and social citizenship in the early part of the twentieth century with universal suffrage, gender equality and a state commitment to welfare underpinning it.

In the Universal Model, there is a difference between national and local welfare, with national administrations taking responsibility for income provision and municipal authorities for service provision. However, even though long-term care services are provided by municipalities, there is very little variation in eligibility for services, which are generally universal and/or set nationally. This provides important protection for the universality of rights to access long-term care services. It also means that citizens are protected from variations in local fiscal and economic conditions: their rights to long-term care are not necessarily contingent on their economic status or that of their municipality. However, this does not necessarily protect them from variations in the quality of services and the introduction of market mechanisms, and individual care payments may threaten to undermine the universality of services.

The final institutional framework which supports the Universal Model is a strong commitment to worker’s rights, in this case, the rights of care workers. Although there is some concern that the introduction of marketization and personalization of care services (in a very limited way) threatens to undermine this, care workers are highly qualified and relatively well paid in this model. As discussed above this is an important contribution to the smaller gender pay gap experienced in this model: but it also means that care work (and by association, women’s work) is highly valued in social terms.

Finally, let’s consider the key actors who play a significant role in making the Universal Model work. The first group is elected policy makers: at both a national and municipal level, there has been a political commitment to maintaining the universality of long-term care services over a sustained period of time. Changes to the design of the system – eg. the introduction of relatively minor efforts in marketization – have not yet significantly undermined this cross-party consensus and political commitment to the maintenance of service provision.

The second group of actors is potential unpaid/family carers. By supporting the ideological commitment to women’s emancipation through engagement in paid work, this means that on the whole, they are not available to provide long-term care to family members. Therefore, any moves to place greater responsibility on family carers are likely to challenge not only political and cultural values, but also the material reality that women are not easily available to provide unpaid care. This is not to say than unpaid carers are absent in the Universal Model: some commentators note that a significant part of the support for older people with low levels of social care needs comes from families, with daughters and daughters-in-law providing the bulk of support (Sigurðardóttir & Kåreholt, Reference Siguroardottir and Kårehol2014). Gendered cultural expectations do limit some of the choice not to provide care in the case of low-level needs (Knijn & Kremer, Reference Knijn and Kremer1997). However, once needs increase, the tendency is either for formal, paid care in the home, or for older people to move to residential or nursing home care. Eight per cent of Icelandic older people are resident in care homes, compared to 2 per cent of UK older people.

Third, the long-term care workforce plays a significant role in ensuring the feasibility of the Universal Model. At the time of analysis, according to national government figures 11.7 per cent of the workforce in Iceland, and 17.9 per cent of the Danish workforce work in health or social care, compared to under 9 per cent of the UK workforce. As discussed previously, the long-term care workforce is relatively highly trained: Danish social care assistants must complete post-secondary training of 8 months and be accredited (NOSOSCO, 2009). There are no formal requirements for UK social care assistants to be qualified, although post-secondary school vocational training is available.

Disabled and older people who need long-term care services are not necessarily very active actors in the Universal Model. Although they may have contributed towards the funding for services through taxation, only in a relatively small number of cases do they directly employ long-term carers: they usually receive services through municipal agencies, where the level of care and tasks undertaken are decided by the provider, not the user of services. Therefore, service users have relatively low levels of agency to direct or improve long-term care services directly themselves in the Universal Model (Table 5).

Table 5. The Universal Model of long-term care measured by Fraser’s (1997) gender equity framework.

What are the ideas, institutions, and actors that make the Partnership Model work? (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999)

Several ideological positions support the Partnership Model. The first is the overarching assumption that the provision of welfare is not solely the responsibility of the state. Instead, the Partnership Model is predicated upon cooperation between the state, the market (both as employers of people buying services and providing the services) and families/individuals (both in the paying for the services and in the provision of care). The second ideological position that underpins this model is the neo-liberal emphasis on the importance of individual choice. Crucially, long-term care policies in the Partnership Model are not based on the assumption that the state OR the family will provide care. Instead, policies are designed so that individuals and families can choose who provides care. However, this model is also underpinned by an unquestioning acceptance of the overrepresentation of the gendered nature of caring: it is overwhelmingly women (and most often low-income women) who chose to provide long-term care themselves. Nevertheless, this model does explicitly value and compensate women for carrying out long-term care work, and does offer family carers the choice NOT to provide care (Knijn & Kremer, Reference Knijn and Kremer1997).

The Partnership Model of long-term care relies institutionally on there being a developed market of care providers at a municipal level. If families cannot choose to have care provided by a high-quality service provider then their choice to provide care themselves is constrained, even if that care is compensated. This model also relies on care work being valued when it is provided for pay: there needs to be a pool of labour willing to engage in care work as a viable career. Care work thus needs to be formalized, with good pay, training and prospects for it to be attractive. Crucially, particularly in Germany, this model was developed at a time when a pool of labour from the former German Democratic Republic was available, as well as young men seeking to avoid armed services national conscription in the Federal Republic of Germany until 2011, who could opt to work in long-term care services instead. Both Germany and the Netherlands offer long-term care qualifications and favourable rates of pay for formal carers compared to the UK (at the time of writing, average market hourly pay adjusted for cost of living for long-term care workers was £11.24 in Germany, £10.02 in the Netherlands and £8.21 in the UK). The Partnership Model of long-term care is also built on strong union support for care workers, and relatively good relationships between unions and the state in negotiating terms, conditions and rates of pay (Table 6).

Table 6. The Partnership Model of long-term care measured by Fraser’s (1997) gender equity framework.

Conclusions

In contrast to previous approaches to welfare state modelling, the findings here indicate that it is possible to use frameworks derived from gender equality measures to examine the outcomes of long-term care policies. Both Fraser (1997) and Platenga et al. (Reference Platenga, Figueiredo, Remery and Smith2009) provide useful measures that can be operationalized in policy analysis to unpick how policies achieve gender equality outcomes. The findings of this research also indicate that theoretical framings of welfare pluralism (Evers & Stetlik, Reference Evers and Svetlik1993) and historical institutionalism (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999) can be usefully deployed in comparative social policy analysis to go beyond describing and modelling different types of welfare regimes. They can be applied to our understanding of the governance of long-term care policies to understand not only how they operate in practice to support or prevent gender equality, but also how context-specific which elements of which policies are: this is vital to understanding how effective such policies might be if transferred to a different context.

Overall, whilst the Universal Model of long-term care policy might offer slightly better gender equality outcomes, it is entrenched in context specific ideas, actors and institutions. Moreover, when this model is threatened by welfare pluralism it can lead to increases rather than decreases in gender inequality. On the other hand, whilst the Partnership Model of long-term care policy might not deliver such marked gender equality outcomes, it is based on a more flexible mixed economy of welfare, and therefore would transfer more easily to other welfare state contexts.

Disclosure

This research was funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Centre grant # ES/L003325/1.

Notes on contributors

Kirstein Rummery is Professor of Social Policy at the University of Stirling and a Senior Fellow of the Centre on Constitutional Change.