Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic presented an unprecedented challenge to the global medical community. Various strategies were implemented to limit disease transmission and to preserve resources for the pandemic response. In March 2020, a recommendation was issued by ENT-UK to adapt telephone triage for the urgent suspected cancer two-week-wait pathway.1 This was proposed in order to maintain sufficient levels of patient care, whilst minimising in-person hospital attendances. As an adjunct, ENT-UK – the official membership body of British otolaryngologists – had also advised the use of the Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator version 2 (‘HaNC-RCv2’), a validated risk scoring system for head and neck cancer based on patient demographics and symptomatology, to assist with the remote assessment process.Reference Paleri, Hardman, Tikka, Bradley, Pracy and Kerawala2

The current head and neck cancer two-week-wait pathway was introduced in 2005 by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK. On this pathway, general practitioners can refer patients with suspected head and neck cancer for fast-tracked specialist appointments. These appointments typically consist of physical examinations including flexible nasoendoscopy (FNE). Early in the pandemic, FNE was classed as an aerosol-generating procedure and, as such, examination in this manner was only targeted at cases where it was deemed to alter management. The absence of physical examination of patients clearly raises concerns that telephone clinics would not be as robust in detecting head and neck cancer compared to traditional face-to-face clinics.

Objectives

This study evaluated our initial experience of adapting telephone clinics for head and neck cancer two-week-wait patients and examined the referral outcomes during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Ethical consideration

The study was registered locally with the hospital clinical effectiveness department and was compliant with the Trust's clinical governance policies.

Reporting guideline

This study was reported in accordance to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (‘STROBE’) guidelines.

Study design and setting

This study was set in a regional specialist head and neck unit in the UK. The study period was from April 2020 to May 2021. A retrospective service evaluation of the head and neck cancer two-week-wait clinic was conducted. Anonymised clinical data in the specialist database maintained by the multidisciplinary team, and clinic letters in electronic medical records, were reviewed.

Patient inclusion criteria

All patients referred on the head and neck cancer two-week-wait pathway between April 2020 and November 2020 were identified. All patients received an initial telephone consultation and were followed up for six months. Patients who received a new cancer diagnosis presenting with head and neck symptoms at any point in this time were included in the study. Patients with cancers that were incidentally diagnosed or were unrelated to the index referral were excluded.

Main outcome measures

Data on patient demographics, the site of primary cancer and the outcome of the initial telephone clinic for the study group were collected. The outcome of the initial telephone clinic was classified into three categories: urgent – involving urgent imaging and/or face-to-face appointments; non-urgent – entailing a watch-and-wait approach or the offer of deferred face-to-face appointments; and discharge. The Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator score was derived for patients included in the study.Reference Paleri, Hardman, Tikka, Bradley, Pracy and Kerawala2

Results

In the seven-month study period, a total of 1062 patients were referred on the head and neck cancer 2-week-wait pathway. Patients’ mean age was 58.9 years (range, 16–98 years). All 1062 patients received an initial telephone consultation and were able to be identified at 6 months’ follow up.

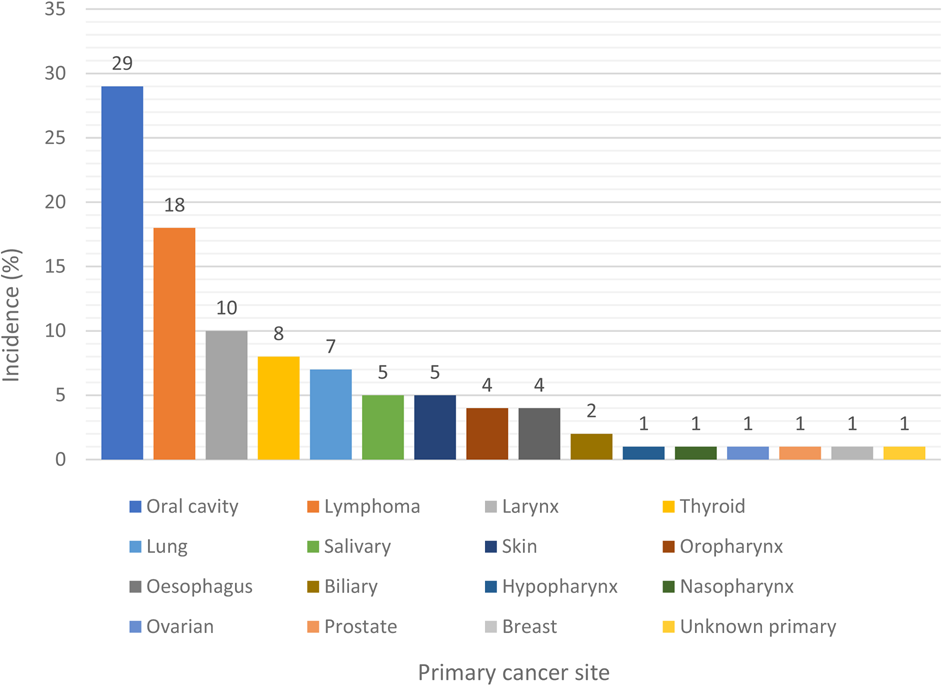

Ninety-eight patients (9.2 per cent) received a new diagnosis of malignancy. The most common types of malignancy seen in the study cohort were oral cavity cancer (n = 29), followed by lymphoma (n = 18), laryngeal cancer (n = 10) and thyroid cancer (n = 8) (Figure 1). Ninety-five patients received a positive cancer diagnosis following the first telephone appointment. Of these 95 patients, 69 had a diagnosis made primarily based on imaging requested following this appointment, and 26 had a diagnosis made at a subsequent face-to-face appointment.

Figure 1. Sites of primary cancer diagnosed in the study group.

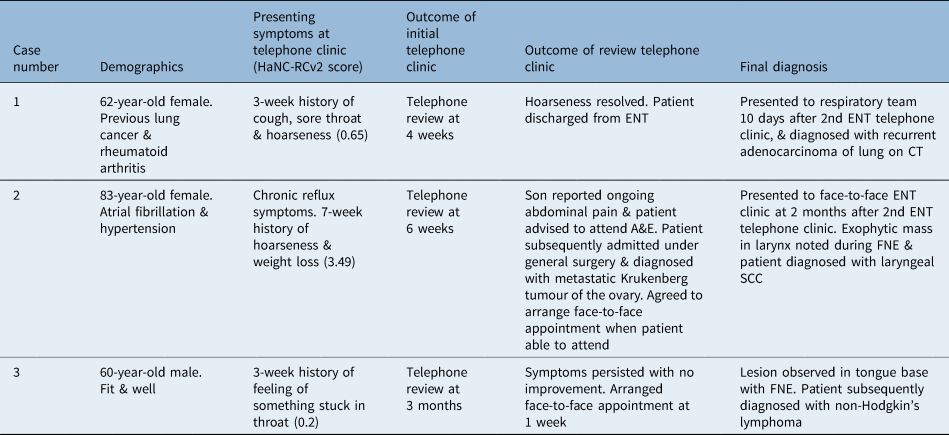

Three patients, all of whom scored as low risk on the Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator, were offered non-urgent follow up after their initial telephone clinic, but were subsequently diagnosed with cancer. This represents a late diagnosis rate of 0.28 per cent. These three patients received a deferred telephone appointment at four weeks, six weeks and three months, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of study cases in the head and neck cancer (HNC) two-week-wait pathway.

The three patients with a late diagnosis were: (1) a 62-year-old female diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma who presented with a hoarse voice; (2) an 83-year-old female diagnosed with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma who presented with a hoarse voice; and (3) a 60-year-old male diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the tongue base who presented with the feeling of something stuck in the throat (Table 1).

Table 1. Study patients with delayed cancer diagnoses

HaNC-RCv2 = Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator version 2; CT = computed tomography; A&E = accident and emergency; FNE = flexible nasoendoscopy; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma

In terms of the Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator scores of the study cohort, 80 per cent (n = 78) were classed as high risk and 20 per cent (n = 20) were classed as low risk.1 All three cases with late diagnoses were classed as low risk in the study.

Discussion

Compared to pre-pandemic data, there was a decline in 2-week-wait referrals to our regional specialist unit during the study period, of 7.3 per cent. This trend conforms with other studies, which also showed a decrease in urgent head and neck cancer referrals during the pandemic.Reference Bhamra, Gorman, Arnold, Rajah, Jolly and Nieto3 The trend likely results from limited access to primary care and altered health-seeking behaviours during the Covid-19 pandemic.Reference Greenwood and Swanton4

Nine per cent (9.2 per cent) of patients referred on the two-week-wait pathway were diagnosed with cancer. This conversion rate is comparable to that in current literature, which is reported to be between 6 per cent and 11.8 per cent.Reference Langton, Siau and Bankhead5 Recent studies have observed a national downwards trend of head and neck cancer two-week-wait conversion rates, which is suggested to be mainly due to an increase in the number of two-week-wait referrals from the community.Reference Langton, Siau and Bankhead5 This reflects the trend seen in our regional unit, with a rise in the number of two-week-wait referrals over the years, outside of pandemic times. There are concerns that this trend could potentially overwhelm secondary specialist services.Reference Pullyblank, Silavant and Cook6

In our study, despite pandemic-related disruption, 100 per cent of the urgent referrals were able to be accommodated within 14 days, without significant impact on the waiting times of routine referrals. It is possible that telephone clinics are more efficient than traditional face-to-face appointments and result in an improved patient flow.Reference Weerasooriya, Stewart and Thomas7

Historically, the most common types of malignancy diagnosed from the head and neck cancer urgent pathway have been oral cavity cancer, lymphoma, laryngeal cancer and thyroid cancer.Reference Mettias, Charlton and Ashokkumar8 The same pattern was observed in this study. This may suggest that the Covid-19 pandemic has not caused any major deviations from the pre-pandemic head and neck cancer referral patterns.

Under the current 2-week-wait pathway, patients with cancer should receive their initial diagnosis within 28 days of the initial referral.Reference Mettias, Charlton and Ashokkumar8 Three cases in the study cohort were diagnosed outside of this window and therefore are considered to be late diagnoses. There are limited data on the late or missed diagnosis rate of the head and neck cancer two-week-wait pathway. Recent communication from ENT-UK suggests that telephone consultations are 1.4 per cent more likely to result in a missed cancer diagnosis compared to face-to-face consultations.1 A recent 16-week prospective study suggested that the late diagnosis rate of the head and neck cancer 2-week-wait pathway was 0.6 per cent overall.Reference Hardman, Tikka, Paleri and ;9 This is comparable to the 0.28 per cent rate found in our study.

The inability to perform physical examinations and diagnostic FNE during telephone consultations is unequivocally a major reason why these cancer cases were missed. It could be speculated that the missed cancer cases would otherwise have been diagnosed by direct visualisation in a face-to-face consultation.

Interestingly, two out of the three missed cancer cases had presented with a hoarse voice. A recent study showed there is limited value in assessing voice disorders over the telephone.Reference Watters, Miller, Kelly, Burnay, Karagama and Chevretton10 Clinicians can easily misjudge the severity of hoarseness during a telephone consultation and offer these patients deferred appointments. Future studies could examine associations between presenting symptoms and late diagnoses in urgent head and neck cancer telephone clinics on a larger scale.

A late diagnosis does not inevitably lead to a worse clinical outcome. Among the delayed diagnoses in the study, only one case, with a longer time to follow up, required escalated intervention because of the late diagnosis; overall prognosis was, however, deemed to be unaffected. The other two cases, although managed outside of the 31- and 62-days pathway, did not receive altered or escalated treatment. This is likely accounted for by the closer follow-up reviews to their first appointments, at four and six weeks.

The limitation of the study lies within the relatively small sample size. Only three late diagnoses were identified, which makes any further analysis into factors associated with late diagnoses non-meaningful. A larger sample size could be obtained by extending the study period. However, this would defeat the purpose of the study, which aimed to evaluate the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the head and neck cancer two-week-wait pathway. Whilst it was not the objective of this study to determine the predictive accuracy of the Head and Neck Cancer Risk Calculator, as this has already been covered by multiple studies,Reference Paleri, Hardman, Tikka, Bradley, Pracy and Kerawala2,Reference Hardman, Tikka, Paleri and ;9 it is interesting to observe that 20 per cent of the study cohort with a positive cancer diagnosis were stratified as low risk, including all three of the late diagnosis cases.

• During the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic, cancer referral guidance recommended a move from face-to-face clinics to telephone appointments

• In a seven-month study period during the pandemic, 1062 urgent two-week-wait cancer referrals were received in our regional head and neck specialist unit

• This reflected a 7.3 per cent decline in two-week-wait cancer referrals compared to pre-pandemic data

• At six months’ follow up, 98 patients (9.2 per cent) had received a cancer diagnosis; 95 had prompt diagnosis and 3 had delayed diagnosis

• The late diagnosis rate was 0.28 per cent, but delayed diagnosis does not inevitably lead to a worse clinical outcome or harm

• Telephone clinics will likely remain in some capacity after the pandemic; telephone clinics maintain patient flow, but could result in late diagnoses

Although cases of Covid-19 are on the decline, telephone clinics will likely remain in some capacity after the pandemic. This study reported our initial experience of adapting telemedicine for the head and neck cancer urgent referral pathway, and found that a small proportion of cancer cases were missed. Clinicians will be mindful that telephone clinics, whilst a pragmatic means to maintain patient flow during the pandemic, could result in late diagnosis and harm compared to traditional face-to-face appointments.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

None declared