Introduction

In the past two decades, participatory-democracy mechanisms have emerged as a means of addressing declining involvement in conventional forms of political participation and low levels of trust in representative institutions. Latin American countries have been at the forefront of this movement, prompting some observers to contend that the source of democratic innovation has moved from the North to the South.Footnote 1 Participatory-democracy theorists argue that active citizen participation serves an educational function in that it can empower those who have traditionally been excluded from decision-making by providing them with learning opportunities, including education in democratic citizenship.Footnote 2 Educational reformers also find a strong link between empowerment of marginalised populations, education and participatory community-development processes.Footnote 3

These theoretical approaches have been criticised, however, for neglecting power dynamics within participatory mechanisms themselves, and for overlooking structural inequalities between women and men. Critics argue that while participatory democrats focus on universal values, masculine gender constructs are built into the very conception of public participation, and male styles of communication are reflected in the design of these mechanisms. These charges have important implications for women's ability to benefit from the educational advantages of participatory democracy. While critical theory is well developed with respect to citizen participation and gender, there is a need for more empirical research focused on the lived experiences of women participants.Footnote 4 Furthermore, the participatory-democracy literature has tended to focus on procedures and outcomes, with less attention paid to the learning dimension, and even less scrutiny of the skills women learn through participatory mechanisms.Footnote 5

This article contributes evidence to address this gap by presenting research conducted with women in three Latin American countries that have experimented with participatory democracy: Venezuela, Ecuador and Chile. It examines common claims with respect to the role of participatory mechanisms as a ‘training ground’ for democracy from the perspective of women in societies where traditional gender roles remain deeply entrenched. The article seeks to answer the following question: What kinds of skills do women learn and to what extent do these skills break down or reinforce traditional gender roles?

Based on original survey data and a series of semi-structured interviews conducted with women in these three countries, my findings suggest that most women develop three types of skills through engagement in participatory mechanisms: administrative, technical and political. These do not differ substantially from the skills that men learn, and I do not find evidence that traditional gender roles are reinforced through the participatory processes. I also find that the enhanced sense of confidence and political efficacy gained through these skills encourages many women to become more engaged outside the private sphere. Yet at the same time, state-sponsored educational processes reject the expression of differences between women and men.

The article begins with a review of the relevant literature on the impact of participatory democracy on skills development, including feminist critiques that question the extent to which participatory mechanisms can benefit women. This is followed by an overview of the participatory architecture that has emerged in Latin America, including the training processes that are available to participants. Following a discussion of the methodology, I present survey and interview data on how women involved in the research experienced the learning processes related to participatory mechanisms in Venezuela, Ecuador and Chile. This includes the skills they developed, as well as spillover effects such as sense of political efficacy. The final section summarises the findings and discusses what we can learn from them.

Gender, Citizen Participation, and Learning

In Latin America, gender differences, along with class and race, have historically underpinned a system that establishes women's ‘place’ in the social hierarchy as second-class citizens. Footnote 6 These patterns begin in the classroom; educational institutions in the region are spaces invested with power that reproduce and legitimise socially hierarchical identities.Footnote 7 In the political realm, institutions and practices are characterised by a stratified social ordering founded on male and class privilege, reinforced by a series of explicit or implied rules that deny women recognition as bearers of rights.Footnote 8 A key expression of gender discrimination involves the exclusion of women from public participation, decision-making and the exercise of power through various formal and informal practices.Footnote 9 Observers note that while states have gradually established formal legal equality between the sexes, these advances have not been supported by an evolution of political culture and genuinely inclusive practices.Footnote 10 Women's political rights and participation are assimilated to a masculine norm; in this way, formal legal equality can have the perverse effect of reproducing inequality through hidden forms of discrimination.Footnote 11 Elizabeth Jelin and Eric Hershberg note that democratisation requires new sets of rules regarding distribution of power and recognition of social actors. This requires not only the expansion of democratic practices, but the development of a new culture of citizenship.Footnote 12

For some, participatory democracy promises to create conditions favourable to deepening democracy and expanding citizenship to traditionally excluded actors.Footnote 13 Proponents of participatory democracy have long argued that citizen involvement in decision-making serves an educational function.Footnote 14 Participation, according to this perspective, can foster the development of skills and knowledge that can help excluded actors to more effectively exercise citizenship.Footnote 15 In her influential work, Carole Pateman argued that participation in local decision-making is a means of ‘learning democracy’. Involvement at the local level is seen as a good place to begin as it fosters psychological qualities required for participation at the national level as well as the development and practice of democratic skills.Footnote 16 John Gaventa argues that citizens must have not only an awareness of policy issues and their implications, but also practical knowledge and skills that can translate into making their voices heard and having influence in the policy arena.Footnote 17 Amartya Sen links development of individual capability for the marginalised to participation in forming solutions to their own problems.Footnote 18

But critics worry that participatory mechanisms will simply reproduce gender hierarchies inherent in ‘traditional’ political institutions, and that privileged actors will continue to benefit from significant advantages in a deliberative process.Footnote 19 These authors argue that participatory-democracy theory has developed with an underlying assumption of universality and without a gender perspective.Footnote 20 Patricia Hill-Collins insists on the need for a dialogue between participatory democracy and intersectionality, noting that state-sanctioned participatory projects can create the illusion of erasing differences in the name of encouraging equality. She warns against theories masquerading as universal and concealing intersectional power relations.Footnote 21 For Nancy Fraser, male styles of expression are reflected in the design of participatory mechanisms.Footnote 22 Styles of expression preferred by non-privileged actors, including women and minorities, may be devalued, even if unintentionally. She criticises the assimilationist tendencies of participatory theories and mechanisms; they discourage the expression of multiple identities and the discussion of ‘private’ interests out of fear that this will be detrimental to deliberation focused on the public good.

In the Latin American context, the ‘on paper’ expansion of political rights has occurred within a framework that continues to reproduce visible and hidden forms of gender discrimination.Footnote 23 Observers appreciate that there are now more spaces for the expression of citizens’ demands and point to the new participatory architecture that has defined the region's democratisation process in the twenty-first century. But they contend that institutional changes, including the development of new invited spaces to promote political inclusion, have not been accompanied by the necessary transformations in attitudes and practices associated with women's political participation.Footnote 24 According to Virginia Vargas, this new and rich participatory institutional framework co-exists with a male-dominated and elite-driven ‘impoverished political practice’ that is incapable of fully recognising marginalised actors as equal bearers of rights.Footnote 25 If patriarchal norms and gender discrimination perpetuate the masculinisation of political spaces,Footnote 26 there is reason to suspect that these patterns will simply be reproduced within participatory mechanisms.Footnote 27 But we have little evidence on how all of this affects the capacity of participatory mechanisms to produce valuable learning opportunities for women.

Schools in Latin America continue to serve as sites of socialisation that maintain gendered social relations and constrain educational alternatives.Footnote 28 Gender stereotypes orient males toward ‘hard’ skills that lead to professional and leadership positions, while women are expected to learn ‘feminine’ skills that limit their future opportunities.Footnote 29 In the long term, these practices hinder the consolidation of women's citizenship by relegating them to subordinate roles and reinforcing under-representation in political positions.Footnote 30 Participatory democracy offers the potential to deconstruct these patterns by providing adult women with opportunities to develop skills such as project management, budgeting and public speaking, as well as knowledge of the political system.Footnote 31 Ensuring that participatory mechanisms produce the educational benefits that proponents hope to see would require gender-conscious institutional design, as well as participant training programmes that recognise gender imbalances and respect a diversity of experiences and social positions.Footnote 32

Until recently, there has been relatively little empirical evidence on the educational benefits of participatory-democracy processes.Footnote 33 The emergence of participatory institutions in the past two decades has provided us with more opportunities to test theory against concrete examples. In the past few years, a growing body of work has found that participation in local budgeting processes generates informal educative experiences in citizenship and democracy. Citizens gain knowledge about politics and citizenship, and develop analytical, leadership and deliberative skills. They can also develop more democratic attitudes and practices.Footnote 34 Looking at cases in Central America, Daniel Altschuler and Javier Corrales find that participation leads to the development of specific skills and that participants are more likely to join and be involved with other organisations.Footnote 35 Oana Almasan argues that, in addition to skill development, participation can lead to empowerment of individuals and groups.Footnote 36 While these studies do not specifically examine the experiences of women, most acknowledge that not everyone is empowered in the same way. Daniel Schugurensky argues that learning and change experienced by participants is highly influenced by certain factors, such as background, their role as participants, and the institutional and pedagogical design of the process.Footnote 37 Josh Lerner believes in the equalising potential of citizen participation but acknowledges that it can also exclude certain groups. He also finds that different participants learn different things, in different ways.Footnote 38 Yet this research does not engage directly with gender or the experiences of women participants.

The handful of studies that have considered the intersection of gender and participatory democracy provide some clues. Janine Hicks looks at the ability of participatory mechanisms to incorporate equity issues with respect to marginalised women in South Africa. She finds that purposeful intervention is required with respect to the institutional design of these mechanisms to ensure equal participation.Footnote 39 In the case of the People's Plan Campaign in the state of Kerala (India), Mariamma George finds that while empowerment may be enhanced with respect to economic benefits, gender oppressions remain entrenched and women's experiences of inclusion are insufficient to contest the various dimensions of exclusion that women face.Footnote 40 Manju Agrawal points out the inherent difficulties in creating participatory spaces that recognise and challenge inequities in power and influence between groups.Footnote 41 Christopher Karpowitz, Tali Mendelberg and Lee Shaker find that women's influence within participatory mechanisms is shaped by the interaction of gender composition and the rules around how decisions are made.Footnote 42 Women are able to benefit from participation when there are more women involved, and when decisions are made by unanimous rather than majority vote, as this requires men to secure their support. While these works provide us with useful tools for further exploring the questions addressed, they do not touch on the educational function of participatory mechanisms.

There is a vast body of theoretical work that interrogates the strengths and weaknesses of participatory democracy, including its educational potential. Theorists view learning through participation as a benefit in itself, because the skills developed and knowledge acquired provide people with tools that can foster a more inclusive citizenship. This may be able to address gender inequalities, particularly with respect to local participation, but we lack empirical evidence. This article addresses these gaps by examining the skills that women learn and the extent to which these skills break down or reinforce traditional gender roles.

Citizen Participation and Training in Latin America

Latin America has been at the forefront of experiments with new mechanisms designed to encourage and channel popular participation in decision-making. One of the defining features of this movement is the idea that popular participation aims to empower those who have traditionally been excluded from decision-making, in part by providing these citizens with the opportunity to ‘learn democracy’ and specific related skills. The three countries studied in this article have developed different models of participatory design. The ‘Pink Tide’ governments of President Hugo Chávez (Venezuela, 1999–2013) and Rafael Correa (Ecuador, 2007–17) claimed a strong ideological commitment to ‘radical’ participatory democracy and created a plethora of participatory institutions, including local citizen councils, to implement this vision. The Chilean state has framed citizen participation as a means of improving governance, enhancing representative institutions and achieving more efficient outcomes, rather than as an alternative model of democratic politics.Footnote 43

With Chávez's ascension to power, the concept of popular democracy was enshrined in the 1999 Venezuelan Constitution as a first step in the ‘refounding’ of the country's democracy. Communal councils (consejos comunales) were formally created by a law passed in April 2006 and have the power to establish and manage programmes in local social and economic development, infrastructure, health, education, housing, sports and other areas. The councils are divided into a citizens’ assembly comprised of all members of the represented community; an executive organ consisting of elected spokespeople (voceros); as well as financial-management, community-oversight and community-engagement units, members of which are also elected by the assembly.Footnote 44 Citizens deliberate and vote on proposals and may seek funding from one of a number of state agencies established for this purpose. Training is provided by numerous central and state government institutions that deliver workshops and produce pedagogical materials.

In Ecuador, participation was promoted as part of a ‘Citizen's Revolution’ by the left-leaning Correa administration. In 2010, the government established various participatory mechanisms, including local citizens’ assemblies. Citizens can form an assembly at their own initiative and can put forward local policy initiatives, promote education with respect to citizen rights, and exercise oversight over decisions made. Training is provided by one of several state agencies. While both administrations became increasingly authoritarian at the central state level throughout the course of their mandates, there is a body of research that demonstrates that participatory mechanisms expanded and deepened democracy at the local level in the 2000s,Footnote 45 although some expressed concern that these arrangements were also deepening clientelistic relationships between participants and the state.Footnote 46

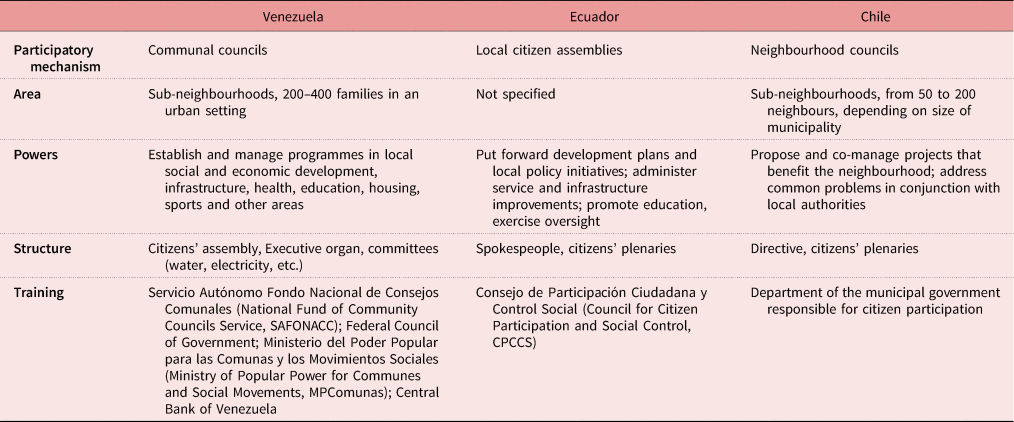

Created in 1968, Chile's neighbourhood councils (juntas de vecinos) were the centrepiece of President Eduardo Frei's (1964–70) Promoción Popular programme. Frei's Christian Democrats identified the low living standards of Chile's poor as tied to lack of political participation and sought to develop institutions that would allow people to participate in addressing their own problems.Footnote 47 The juntas lost much of their independence during the Pinochet dictatorship, but regained some vitality in the 1990s. A 1997 law more clearly defines the functions of the councils, which include proposing and managing projects that benefit the neighbourhood and addressing common problems and development issues in conjunction with local authorities.Footnote 48 Training is offered by the department of the municipal government responsible for enacting citizen-participation initiatives. Table 1 summarises some of the key characteristics of participatory mechanisms in each country.

Table 1. Participatory-Mechanism Characteristics

Source: Author's elaboration.

State or municipal agencies charged with overseeing citizen participation offer courses, workshops and training materials to anyone involved in participatory mechanisms. The content ranges from preparing budgets and project plans to more theoretical – and often ideological – content regarding citizenship and participation.Footnote 49 Yet in all three cases, there is little evidence of attention to gender in the design of participatory training programmes. Materials produced by state institutions group women into broad categories of traditionally marginalised citizens, which include poor men and women, Indigenous peoples, and racialised communities. Overall, state institutions tend to ignore or discourage the expression of differences and promote participatory mechanisms as spaces where all citizens are equal.

Methodology

The research was conducted from September 2012 to May 2013. The data consist of a survey questionnaire, a series of semi-structured interviews, and document analysis. While this article focuses on women's perspectives, I have included men's responses when they serve to demonstrate differences in skills acquisition. To the extent possible, I looked at a representative sample of participatory mechanisms in each country, selecting cases according to a diverse case method to achieve a certain level of variation on a number of important dimensions.Footnote 50 I selected 15 cases to reflect population distribution as well as a number of other factors: important regional/cultural differences, ethnic representation, political cleavages, socio-economic factors, and the urban vs. rural divide.

In Venezuela, my fieldwork focused on the urban areas of the north-western part of the country, as this is where about 93 per cent of the population lives. I distributed surveys to six communal councils: two in Caracas (Sucre and 23 de Enero), one in Vargas State (Macuto), one outside of Valencia (Guacara), one on the coast (Puerto Cabello) and one in the interior (Mérida). In Ecuador, I sought to capture both the highlands and coast as the population is divided more or less evenly between these two regions, which have also represented the primary political and cultural divisions in the country. Cases include a local assembly outside of Quito (Calderón parish), a rural assembly from the northern highlands (Montúfar), one from a small urban canton in the southern highlands (Paltas), a mid-sized urban area on the coast (Manta) and a small coastal town (Bahía de Caráquez). Regional differences have not been as historically significant in Chile but socio-economic divisions run deep. I selected three cases from the greater Santiago area (high-income Providencia, medium-income Maipú and low-income La Pintana) and one from Valdivia in southern Chile (semi-urban Cayumapú).

I selected citizen participants with the help of the spokespeople (representatives) from each participatory mechanism. In order to reduce bias and to achieve a representative sample of participants, I sought to select participants based on gender, age, occupation, role in the participatory mechanism, and frequency of participation. In most of the cases, this process was facilitated by the existence of membership lists which include demographic information. Where such lists were unavailable, I asked spokespeople to assist with the development of a representative sample of participants based on their knowledge of the membership. I then established lists of names based on the above criteria and contacted individuals; those who accepted were asked to complete the survey questionnaire. Through snowballing, I also included non-participants by asking subjects to identify individuals who had ceased involvement in the participatory mechanism. This allowed for the inclusion of voices more critical of the participatory process in each country.

I distributed just over 1,000 survey questionnaires and received a total of 446 from the 15 participatory mechanisms. This included 27 to 31 individuals from each of the cases. Over half of respondents (53 per cent, n = 236) were women and the age distribution suggests that most participants were above the age of 40 (4 per cent aged 16–25; 21 per cent aged 26–40; 45 per cent aged 41–60; 31 per cent aged 61 and above). With respect to socio-economic status, the largest number of respondents (26 per cent in Venezuela, 23 per cent in Ecuador and 17 per cent in Chile) can be identified as precarious/unskilled workers (generally in the informal sector) while many women also identified as homemakers (24 per cent, 17 per cent and 14 per cent, respectively). A minority of respondents (3 per cent in Venezuela, 9 per cent in Ecuador) identified as professionals (individuals with university degrees or jobs requiring advanced skills). Chilean neighbourhood-council participants were more likely to be retired (21 per cent) and professional (16 per cent). The survey is primarily quantitative and asks about various dimensions of how individuals have experienced participatory mechanisms in their locality. The research presented in this article focuses on the skills that citizens have acquired through participation. A number of retrospective questions were also asked to gauge the impact of participation on individuals’ lives.

Considering the theoretical work on participatory democracy, Jane Mansbridge notes that the educative effects of participation postulated by theory are likely to take subtle forms that cannot easily be captured in empirical studies.Footnote 51 This article concentrates on more tangible sets of skills that citizens can observe and articulate through their lived experiences. Following Altschuler and Corrales, the questionnaire asked participants to identify specific skills they had learned by providing a list of skills developed by the researcher following an analysis of documents and pedagogical materials produced by state agencies responsible for citizen participation in each country.Footnote 52 The survey instrument also allowed for individuals to fill in any skills that were not explicitly mentioned on the questionnaire.

I then used the demographic information collected through the questionnaire to identify a representative subset of participants to interview from each mechanism. I used this information to develop a profile of each mechanism and a sample of respondents that provides variation along key variables discussed above for the surveys. I conducted 136 semi-structured interviews (49 in Venezuela, 46 in Ecuador and 41 in Chile), interviewing eight to ten individuals from each of the 15 cases. Of these respondents, 56 per cent (n = 76) were women. The interviews were intended to further explore issues addressed in the quantitative surveys by allowing participants to discuss their lived experiences as learners with respect to how skills and knowledge acquired have affected their sense of political efficacy and contributed to their capacity to participate beyond their local participatory mechanism. I also interviewed officials from various state and local government departments and agencies for additional context. The recordings of the interviews were transcribed and analysed using a multiple-step process to identify themes related to learning outcomes. I first conducted a careful content analysis of all transcripts, which involved reviewing them several times. This entailed creating a series of codes (categories) based on the variables to be studied, searching for these in the data and analysing the resulting categories for context. I next conducted a more intensive thematic analysis by creating new categories (codes) from the process of analysing the data. Relevant chunks of each transcript were coded (open coding). Finally, a third step involved stepping back to examine the various categories that emerged and making links between these where relevant (axial coding). First names of the interviewees are mentioned only for those individuals who provided consent.

Given that this research looks at skill development before and after participation, the research must rely on the memory and perceptions of participants. Participant perceptions are routinely used to measure the outcomes of participatory processes, although it is recognised that recall bias is impossible to eliminate when people are asked about past experiences. To some extent, this problem was offset by the fact there was considerable consensus in most cases around the questions discussed in this article. I used a number of common strategies to address recall bias in research on the outcomes of citizen participation, including employing more than one data collection method (survey, interview, document analysis) and triangulation.Footnote 53 I used triangulation whenever possible (in addition to asking participants, local officials and a number of non-participants or former participants were asked the same questions). I also used available documentation (project plans, budget information) to back up the information provided by informants (i.e. do training programmes really include the content that participants recall learning?).

I analysed relevant documents produced by departments and agencies charged with delivering formal learning programmes to citizen participants. The primary purpose of this analysis was to determine the types of skills and knowledge taught. I also analysed the texts to identify linguistic and rhetorical mechanisms that could shed light on how state agencies engage with gender in these materials. I used keyword analysis to identify recurring words surrounding gender and the context in which those words are used and normalised.Footnote 54 These included administrative documents, promotional materials, training manuals, websites and online course content. I analysed a total of 64 such texts (27 from Venezuela, 18 from Ecuador and 19 from Chile).

Learning, Participation and Skills

Of participants across the 15 cases studied, 52 per cent are women. There is relatively little variation between the three countries: women make up 51 per cent of citizen participants in the Venezuelan cases, 56 per cent in Ecuador, and 48 per cent in Chile. Women are also well represented in leadership roles: 54 per cent of members from the elected executive bodies of the 15 councils studied are women.

It is possible to divide learning experiences into two broad categories: skills acquired through formal learning provided by government agencies to participants in the form of workshops and pedagogical materials, and praxis-based learning that develops from involvement in participatory mechanisms. Formal learning can be either ongoing or ‘one-shot’, the latter usually involving a single workshop or series of workshops delivered early on in the participatory process.

The survey reveals that, of the respondents, 84 per cent of Venezuelans (n = 159), 47 per cent of Ecuadoreans (n = 73) and 32 per cent of Chileans (n = 35) reported receiving direct formal training. Of those who reported formal training, 54 per cent (n = 86) in Venezuela, 63 per cent (n = 46) in Ecuador and 57 per cent (n = 20) in Chile were women. This pattern persists when looking at the duration of training: women were more likely than men to have received ongoing training over a period of several months or more. Of those women who had received training, 74 per cent of Venezuelans (n = 64), 54 per cent of Ecuadoreans (n = 25) and 41 per cent (n = 8) of Chileans reported various formal learning experiences over an extended period. In contrast, over half of men who had received training in each of the three countries reported a one-shot workshop experience.

While this is a positive development in that women are offered ongoing learning opportunities in support of their roles as citizen participants, the reasons provided for the gender gap in ongoing formal training may reinforce traditional gender roles. Most interview respondents attributed it to the fact that women were less likely to be employed outside of the home and have more time to attend the workshops. Because training is generally offered at the neighbourhood level, attending sessions was considered to be more feasible. A communal-council participant from a working-class Caracas neighbourhood expressed a sentiment similar to that of many of her peers: ‘We [women] are busy, we have families but [communal] councils are in our neighbourhoods, they are close to us, it is easy to participate for anyone who wants to, they come to us.’ Others insisted that it is a positive thing for women because ‘We can bring our daughters to these workshops, and many of us do. I bring my teenaged daughter with me, and she also learns about how to exercise her rights as a female citizen. I like to see this, she is learning things that will make her stronger as a woman.’

Women were more likely than men to have experienced learning outcomes. Nearly three-quarters of women (73 per cent, n = 169) and 60 per cent of men (n = 129) claimed to have learned at least one new skill, while 65 per cent (n = 151) of women and 52 per cent (n = 111) of men reported learning several new skills. There is significant variation between the three countries, with Venezuelan women and men more likely to report learning outcomes (see Table 2). This is likely attributable in part to the fact that Venezuelan communal-council participants received more formal learning, whereas Chilean men (those who received the least) reported the lowest levels of skill development.

Table 2. Number of New Skills Learned

Note: Respondents were asked how many different types of new skills they believe they have learned through involvement in their country's type of participatory mechanism.

Source: Author's elaboration based on primary data.

The surveys demonstrate that participants develop three categories of skills though engagement in participatory mechanisms: organisational/administrative, technical and political. Organisational and administrative skills involve organising meetings, working in groups, effective public speaking (including deliberation), developing meeting agendas and documenting meetings. Technical skills include using computers and the Internet to find and disseminate information, preparing budgets and developing project proposals. Political skills are related to knowledge of citizens’ rights, legislation and ‘how things work’. This includes understanding how to seek support for a project, knowing which institutions and agencies do what, and understanding procedures such as making a formal complaint or obtaining funding. While participants demonstrate learning outcomes in all three areas, the third category (political skills) is somewhat more complex in that it involves programmes that introduce crafted political messages and establish clear parameters around citizenship.

Survey questionnaires asked participants to determine whether they possessed a given skill before and after participating in their communal council or local citizens’ assembly. Overall, women were more likely than men to have developed new skills across the three broad categories and most of the subcategories. The data in Tables 3–5 present the baseline (per cent of respondents that possessed the skills before involvement in their participatory mechanisms), and the percentage of respondents that possessed the skill following a period of participation (learning outcomes).

Table 3. Organisational/Administrative-Skills Acquisition before and after Involvement in Participatory Mechanism

Source: Author's elaboration based on primary data.

Table 4. Technical-Skills Acquisition before and after Involvement in Participatory Mechanism

Source: Author's elaboration based on primary data.

Table 5. Political-Skills Acquisition before and after Involvement in Participatory Mechanism

Source: Author's elaboration based on primary data.

Organisational/Administrative Skills

Organisational and administrative skills were the most commonly identified learning outcomes. Most women reported knowing how to call and participate effectively in meetings and to work in groups. Many had learned public-speaking skills through participating in debates and the deliberative processes that are integral to the working of these mechanisms. Responses demonstrate that participants were more likely to have these skills after than before their experience in participatory mechanisms, with significant increases across the board (see Table 3).

In Venezuela, the baseline was higher in all cases, which can probably be attributed to the country having (at least in its recent history) a stronger tradition of social organisation in working-class neighbourhoods. Many women had previously been engaged in civil-society organisations that pre-date the Chávez administration. Thus, over half already felt they had strong skills and experience of participating in meetings and working in groups, although fewer had developed public-speaking skills, or experience of organising and managing a meeting. Chilean civil society, in part due to a recent history of repression, has been relatively weak vis-à-vis a strong state. This is reflected in the weaker baseline for organisational skills.

Across the three countries, the surveys demonstrate a significant rate of increase in all five administrative/organisational categories. Dramatic increases are observed with respect to administrative tasks such as creating agendas / taking minutes and organising/managing meetings (210 per cent and 129 per cent, respectively). These skills, particularly the former, may be considered gendered. For men, the rate of increase for creating agendas / taking minutes was only 37 per cent, compared to 210 per cent for women. This may suggest that women were relegated to ‘secretarial’ roles within their participatory mechanisms. However, the most significant rate of increase for women is in public speaking (216 per cent), a traditionally ‘masculine’ skill in machista societies. This theme emerged frequently in the interviews and was associated with greater confidence and ability to have a voice in the public sphere. During the interviews, many women expressed sentiments similar to Raquel, a homemaker from a rural community in Venezuela:

Being able to speak in a public setting and speak with confidence, this is one of the most important things I learned though this experience. Before participating in the [communal] council, the thought of speaking my mind like that, in front of neighbours and strangers, including men, well, it would have terrified me. I was always taught I was not supposed to have strong opinions as a woman. Council participation encouraged me to see that my opinion counts as much as anyone else's and I learned how to express myself.

Far fewer men said that they had developed public-speaking skills, although the number of men who claimed to possess these skills prior to participation was higher. The rates of increase for the other two categories – participating in meetings and working in groups – were lower for women (46 per cent and 52 per cent) but this is likely due to the fact that the baseline was higher in both cases.

Technical Skills

Compared with organisational/administrative skills, we see a lower baseline for the four sets of technical skills addressed in the survey. The exception is Internet use, for which the baseline is relatively high in the three countries. Following a period of involvement in participatory mechanisms, 58 per cent of Venezuelan women and 50 per cent of Ecuadorean women claimed learning outcomes in Internet and computer skills, up from 42 per cent and 33 per cent, respectively. According to the women interviewed, these skills were necessary in order to find information they required to fulfil their roles as citizen participants. As Ketty, a domestic worker from Manta (Ecuador) pointed out: ‘As responsible participants we need to make informed decisions, and to make informed decisions we need information. Information about current laws, about policies, about costs, and many other things. This means we need to be able to search for this on the Internet, and this was a major skill developed from being in the council.’

The increase in Chile is much smaller, because 73 per cent of Chilean women already had computer skills prior to involvement in neighbourhood councils, a finding which reflects the higher level of socio-economic development and Internet penetration in that country.

Venezuelan communal-council participants receive training in all four of these technical-skills areas and women in that country demonstrate the most significant learning outcomes. While the number of men who had developed skills in budget preparation, proposal development and project management was slightly higher following a period of engagement in participatory mechanisms, the surveys show that the pre-participation baseline was higher for men and the rate of increase was significantly higher for women. Following participation, 35 per cent of women feel comfortable preparing budgets to manage money their communal councils have received, 24 per cent have learned to write proposals to request funding for projects, and 20 per cent agree that they have developed project-management skills. This indicates rates of increase of 79 per cent, 130 per cent and 216 per cent respectively for the three skill sets, compared with 25 per cent, 8 per cent and 13 per cent for men.

The rates of increase for Ecuadorean and Chilean women were only slightly lower, but both the baseline and the percentage of participants who achieved these learning outcomes through their involvement in a local assembly are lower. Relatively small numbers of women felt able to prepare budgets, write proposals and manage projects following participation, and skills acquisition in these areas was lower than for men across the board (19 per cent, 17 per cent and 6 per cent of Ecuadorean women gained these three skills compared with 29 per cent, 20 per cent and 9 per cent of men; and 19 per cent, 10 per cent, 4 per cent of Chilean women compared with 25 per cent, 20 per cent and 20 per cent of Chilean men). While this is in part attributable to a lower pre-participation baseline for women, the rate of increase is higher for women (for example, a 33 per cent budget-preparation rate of increase for Ecuadorean men vs. a 100 per cent rate of increase for women, and an 18 per cent proposal-writing increase for men vs. a 75 per cent rate for women). This can be read as a positive development, as it suggests that participatory mechanisms can serve as a training ground for women to develop skills that have traditionally been perceived as the domain of professional men.

While the overall numbers may seem low, particularly in Ecuador and Chile, relatively few citizens in those countries receive training in all of these skill sets. While training is available to everyone, individuals are likely to enrol in workshops based on their responsibilities in the participatory mechanism. Those who are members of the financial unit, for example, are more likely to require training in budget management, while council presidents are inclined to seek broader project-management skills. Still, women that did acquire one or more of these skill sets were extremely positive about the quality of the training they received during the interviews. As Yelitza from a rural community in Venezuela stated: ‘Many of us women do not have much formal education, it limits our ability to contribute to organisations that we participate in. Where would I have learned to prepare a project proposal? They came in and gave workshops on how to do these things, so now I feel I can really contribute to making changes in my community.’

Many of the women interviewed also discussed implications for their participation in the labour force. They pointed out that while they lack formal education, being able to manage budgets and write basic proposals are marketable skills that can improve their employment prospects, which in turn provides them with greater autonomy. A participant in Guacara presented a perspective typical of those expressed in the interviews:

The training we receive on how to make budgets and plan our own projects, this helps us to improve our own communities and it makes things more even. But it also gives us skills we can use to get better jobs. Many women from around here, if they work at all, they work as domestic workers [empleadas] for rich people. They are poorly treated because it is assumed they can't get other jobs. With the skills I learned through the council, I was able to get a better-paying office job.

The development of technical skills and the variation between the two countries appear to be attributable to formal learning opportunities provided. We have already seen that Venezuelan participants were more likely than their counterparts in the other two countries to participate in sustained formal learning, and these types of skills were also a focus of formal workshops and materials developed by state agencies. This was confirmed in the interviews: 72 per cent of Venezuelan women interviewed who had received formal training cited these technical skills as being an integral part of their programme, while only 34 per cent of the Ecuadoreans could recall learning these types of skills.

Political Skills

Political skills include understanding how to seek political support for a local problem or initiative, procedures for submitting a complaint regarding issues such as public-service delivery or corruption, understanding how procedures and institutions work at various levels of government, and knowledge of legislation and citizens’ rights. Across the three countries, the average rates of increase for women participants are 146 per cent for seeking political support; 100 per cent for submitting a complaint regarding issues such as public-service delivery or corruption; 150 per cent for understanding procedures and institutions; and 197 per cent for knowledge of legislation and rights. Their male counterparts experienced much lower rates of increase of 57 per cent, 60 per cent, 64 per cent and 65 per cent for the same four skill sets. While the pre-participation baseline for men was higher in all cases, the surveys demonstrate that following a period of involvement in participatory mechanisms, women were more likely than men to have achieved learning outcomes in this area.

In Venezuela, women's knowledge in all four areas surpassed that of men (see Table 5). In Ecuador, more women than men claimed to have developed knowledge with respect to submitting complaints and understanding their rights as citizens. For the other two subcategories, the numbers are very close although the percentages are higher for men because there are more women in the overall sample. Thus, with respect to political skills, not only were the rates of increase significantly higher for women, but the actual numbers of women who had achieved learning outcomes through participation were more significant. Chilean men were somewhat more likely than women to have developed political knowledge and skills through their neighbourhood councils, although the rate of increase for Chileans is lower for both sexes in this category.

We again see a higher baseline in Venezuela but significant skills acquisition in both that country and in Ecuador. This is perhaps not surprising, as these areas are a focus of training programmes offered by government agencies in these two countries, and most women interviewed indicated that they lacked this knowledge prior to their involvement in participatory mechanisms. Chilean citizens receive minimal formal political-skills training and therefore must rely on indirect learning through practice; the rate of increase with respect to political skills is significantly lower.

As with technical skills, the women interviewed suggested that this knowledge helped them beyond the participatory mechanism or local-level politics. While they frequently discussed the job-prospects dimension of technical skills, women tended to associate political skills with empowerment and argue that such knowledge helps them to develop as citizens. Some attributed their new knowledge directly to the experience of participation, as in the following observation offered by a homemaker from the outskirts of Quito: ‘At first, it was difficult [to participate] because I didn't know anything about how things work or even what my own rights were. After spending a few months participating in the assembly, I started to know a lot about the Constitution, about laws, about where to go to get certain things done.’

Others identified the training provided by state agencies as the most significant factor, as represented by a comment by Blanca from Caracas:

We don't learn these things in school and many of us around here didn't have the chance to study at university. So, the programmes provided for people in communal councils teach us about our own political system and institutions, how they should work and what we can do to make them work for us and not just for the few who have special knowledge.

There is also evidence that the skills women developed enhanced their confidence and their understanding of their roles as citizens: 71 per cent of women surveyed agreed that the knowledge they gained about politics, policy and institutions makes them more confident with respect to exercising their democratic rights. When asked whether they believe that they and their neighbours are able to have greater influence on local political decisions, 66 per cent of women surveyed across the three jurisdictions responded affirmatively. This confidence appears to have an impact on their willingness to engage in the public sphere; 60 per cent of women in our sample believed that they are more likely to participate in associations or public meetings due to the knowledge they have gained through political-skills training.

More so than the other two categories, however, the political-skills component of participatory education programmes is heavily influenced by ideological and political frames. In Venezuela and Ecuador, training for those involved in participatory mechanisms is provided by numerous central-government institutions. Discourse analysis of the promotional and training materials as well as other texts (including forms for requesting funding and budget-development guides) produced by the various agencies charged with managing citizen participation confirms these discursive patterns. These materials place ‘el pueblo’ in the role of ‘protagonist’ and define citizenship as participation in a collective project that strives to democratise politics to ‘achieve the common good’. Yet, while training clearly encourages citizens to insist on having a voice in decisions that affect their lives, there is little differentiation between women and men. In fact, learning materials discourage the discussion or recognition of gender or ethnic differences that would dilute the power of ‘el pueblo’ or permit the introduction of ‘private’ interests. Furthermore, the topics discussed – primarily local needs such as improved infrastructure and social development – tend to determine limits around the scope of participation that is deemed relevant and worthy. A teacher from Mérida reflects on just one aspect of what this means for women:

What is lacking at this point is public participation in higher-level issues […] Many women want to debate the question of abortion, which is still illegal in Venezuela. Well, the communal councils do not allow us to engage in such a debate. They aren't designed for that and they are focused on local issues. So where can we [women] citizens participate in debate over the question of abortion? There are no mechanisms for that.

In Chile, there is no national-level education agenda on citizen participation, although certain municipalities offer such training and central-government departments have developed materials to explain the new participation law and its implications. Discourse analysis reveals a focus on co-governance, efficiency, sustainability and communication. Again, there is little attention paid to gender, and the assumption appears to be that women and men can participate equally. Chilean materials are, however, less prescriptive than those in Venezuela and Ecuador with respect to preferred means of political participation. While training in the latter two countries encourages citizens to participate in ‘radical’ mechanisms designed by the state, Chilean programmes studied refer to a wider range of organisations recognised as legitimate forms of participation; these may include mechanisms established by state legislation (such as neighbourhood councils) but also civil-society organisations autonomous from the state.

Participants also tended to adopt the language found in training materials. During the interviews conducted with individuals in Venezuela and Ecuador, popular participation is contrasted with representative democracy in a manner that frames the former as noble and productive and the latter as corrupt and ineffective. Other examples of the use of ‘popular’ as a positive descriptor include popular will (often contrasted with ‘selfish’ private interests), popular sovereignty (often contrasted with elite dominance) and popular power (often contrasted with rule by the few). These terms were generally applied in an adversarial context in which ‘el pueblo’ is required to defend itself against right-wing and/or elite forces determined to strip the average citizen of her power, as in the assertion that ‘the Right constantly tries to block popular power’, commonly expressed in both countries. Still, as some of the examples in the article suggest, many women tended to adopt a gender identity when discussing their role in participatory mechanisms despite the fact that state training programmes do not encourage this. They are therefore conscious of women's role in the participatory process (which, as we have seen, they generally view in a positive light.)

Discussion

At the time of writing (2022), developments in the region demonstrate the precarious nature of participatory democracy. Following the death of Chávez in 2013, the sharp drop in oil prices plunged Venezuela into a deep economic crisis, while the increasingly authoritarian practices of Chávez's successor Nicolás Maduro have generated ongoing political instability. In all three countries, the region's economic downturn means that less resources are available for participatory mechanisms. These developments have demonstrated the fragility of the gains women have made through citizen-participation initiatives. But administrations across the political spectrum support the principles of participatory democracy, and participatory mechanisms will remain part of the region's political architecture. It is therefore important to examine the extent to which they disrupt masculinist educational and political practices.

Latin American social and political structures are characterised by a system of social stratification that relegates women to subordinate positions in the public and private spheres.Footnote 55 This social order begins with educational institutions. Scholars of gender and education understand classrooms as sites where gendered relationships are constructed.Footnote 56 In Latin America, schools – and universities – reproduce gendered skill sets, behaviours and expectations.Footnote 57 Through sexist content and gender mainstreaming, gender roles are normalised; education plays a key role in reproducing inequality and hierarchy between men and women.Footnote 58 The gendering of skills, common in both educational and workplace settings, refers to a binary system that associates certain types of skills with masculinity and others with femininity.Footnote 59 Males are more likely to possess technical skills and feel more comfortable with public speaking, while women are linked to support roles and secretarial skills.Footnote 60 In Latin America, educational institutions reinforce the gendering of skills that men and women learn, which leads to various forms of segregation.Footnote 61 But these patterns also determine how citizenship is constructed and exercised. These practices have the long-term effect of limiting the consolidation of women's citizenship; they lead to the internalisation of differentiated gender norms and expectations with respect to how individuals can and should exercise citizenship.Footnote 62 The research presented in this article supports theoretical frameworks that present participatory mechanisms as ‘schools’ for citizenship and democracy. The findings suggest that women in societies characterised by male-dominated institutions can achieve important learning outcomes and a sense of political efficacy through participatory mechanisms. They also confirm some of the concerns expressed by scholars such as Jelin, Vargas and Fraser, but only to a certain extent.

On the one hand, women are as likely as men to develop new skills and knowledge, and the skills women learn do not appear to be strongly gendered. While one may expect women to have developed more ‘feminine’ skills through training or through being relegated to certain ‘secretarial’ roles in learning through praxis, the results suggest that this is not the case. Many women gained valuable expertise in areas traditionally associated with ‘hard’ or ‘masculine’ skill sets: public speaking, developing project plans and budgets and using the Internet for information-seeking. Women were more likely than men to develop political knowledge that marginalised citizens often lack, and that can support collective or individual efforts to participate more effectively in political life. The interviews also provide some evidence of attitudinal changes toward democratic participation. Women participants developed a greater sense of confidence about their role as citizens. This supports what some of the more optimistic theorists hope will emerge from participatory democracy. Many women cited the skills and knowledge gained through participatory mechanisms as an important factor in developing confidence and a sense of political efficacy. They claimed that they feel more comfortable speaking and participating in the public sphere, and that they are more likely to be taken seriously due to this increased knowledge.

At the same time, theoretical concerns of participatory-democracy critics are also reflected in the findings. Institutional design of participatory mechanisms and pedagogical practice are focused on the collective ‘public good’; the expression of needs specific to women is discouraged. This pre-empts any discussion of issues such as abortion, domestic violence, salary inequalities between men and women, and so forth. These patterns can be read as establishing a preferred scope of citizenship (which is assumed to be universal) and a distinction between forms of exercising participatory citizenship that are ‘legitimate’ and those that are framed as either ‘illegitimate’ or ineffective. It is expected that gender differences will be bracketed within participatory mechanisms; differentiating between women and men is perceived as divisive and counter to the common good.Footnote 63

There are a number of implications for the long-term impact that these participatory learning experiences can have on women. Participatory democrats have long argued that citizen participation can enhance quality of life and improve the quality of democracy. While these two goals are certainly important, achieving a truly participatory citizenship that alters the power dynamic between dominant and subjugated social groups requires us to pay attention to a third dimension: the improvement of participants themselves through the development of skills and knowledge. Learning certain ‘marketable’ technical and administrative skills provides women from lower socio-economic strata with access to a broader job market, including office jobs. In a region where the majority of poor women in the labour market work as domestic workers or in the informal economy, this has the potential to make a difference in the lives of women who can use these skills to acquire office jobs. Higher salaries and better working conditions can allow women to gain more autonomy and agency.

The educational function of citizen participation can create new opportunities for the development of agency among disenfranchised women and has the potential to address broader issues of unequal participation by providing women with knowledge and skills to engage in the public sphere beyond their local participatory mechanisms. Political knowledge and skills can provide women who have always been excluded from political life with an enhanced sense of political efficacy, as well as a greater understanding of their rights and how to enforce these. These experiences can therefore allow participants to become better informed and more confident about participating in the public sphere; ‘learning democracy’ locally can support involvement at higher levels. There is now a segment of the population that has experienced some form of inclusion in decision-making and perceives this as a fundamental right. However, the fact that issues of particular interest to women are excluded from the participatory process, including the education component, suggests that participatory mechanisms are built on the assumption of undifferentiated citizens and without the recognition that men are historically more advantaged. Mechanisms should allow for the expression of distinct voices around gender. Different social groups have different needs and experiences; women should feel comfortable expressing these throughout the participatory process.

How can participatory learning experiences be designed in such a way as to address common needs while recognising the distinct experiences and needs of women and other traditionally marginalised groups? Teasing out the conditions under which participatory mechanisms produce learning experiences for women may provide some clues. In all three countries, training programmes for participants and the rules that dictate participatory processes themselves discourage the expression of gender-related issues and grievances. This was the primary source of dissatisfaction among participants. It can be resolved by incorporating an intersectional perspective into the learning processes that considers the hierarchical nature of power and the interaction of different social identities, such as gender, race and sexuality. Acknowledging gendered social relations and encouraging women to express related grievances would go a long way toward deconstructing the inequalities produced through educational institutions and would enhance the benefits of participatory mechanisms as schools for democratic citizenship.

The research did not reveal significant within-country variation between individual cases, but there are differences across the three countries with respect to the design of participatory mechanisms and related training programmes. While participants can learn by doing, the cross-country comparison reveals that the existence or absence of training opportunities appears to be an important variable. Venezuelan women were more likely to develop various sets of skills, followed by Ecuadorean participants, while Chilean women reported the lowest rate of increase. This can be attributed to the far more comprehensive, ongoing training programme established for communal-council participants in Venezuela. Agencies have developed a coherent pedagogy, delivered through various channels, on topics such as developing a budget, writing project proposals and guidelines for community-infrastructure projects, citizens’ participatory rights, how various state institutions fit into the picture, etc. Ecuadorean state agencies charged with promoting participation have also developed a ‘curriculum’ that includes in-person workshops and online courses. These teach citizens about relevant legislation and guide people with respect to how to set up citizen assemblies, but do not appear to be as comprehensive in terms of budgeting and project-management skills. In Chile, training for participation is less common than in Venezuela and Ecuador. When provided, training is usually offered by the department of the municipal (communal) government responsible for enacting citizen-participation initiatives, although it is rarely required and is often provided in a one-shot format. All of this suggests that training opportunities should be ongoing, although such efforts must not overburden participants who have busy lives. Additional training for those who feel they require it, including public speaking for individuals who are intimidated about expressing themselves in a public forum, could be beneficial.

If, as proponents contend, participatory mechanisms serve as an equalising educational function and as a training ground for democratic citizenship, they may offer benefits to women in societies characterised by traditional gender hierarchies. These participatory learning processes have the potential to deconstruct sexist patterns of socialisation by providing adult women with opportunities to learn life skills and develop knowledge that supports the exercise of agency and citizenship. Participatory institutions are primarily intended to address the problems faced by poorer socio-economic groups who have been excluded from decision-making. They are not designed to account for other dimensions of social exclusion, such as gender. Consequently, participatory democrats and those charged with designing participatory institutions need to understand the impact of multiple, overlapping social identities on the experiences of citizens and how this affects the power dynamics. These understandings must be integrated into training that participants receive, which should include gender-sensitivity content. Further research should look more closely at the institutional and pedagogical design elements that enhance the capacity of women to develop skills while also engaging with issues that are of particular interest to them.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors of JLAS, as well as the anonymous peer reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments on this paper.