Introduction

There is a general consensus that allowing workers to speak out can bring relevant issues to light and thus contribute to problem-solving, organisational growth and performance improvement (Bashshur & Oc, Reference Bashshur and Oc2015; Chamberlin, Newton, & Lepine, Reference Chamberlin, Newton and Lepine2017; Kim, MacDuffie, & Pil, Reference Kim, MacDuffie and Pil2010). Employee voice, defined as any opportunity and way through which employees express ideas and opinions within the organisation (Van Dyne & LePine, Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998; Wilkinson & Fay, Reference Wilkinson and Fay2011), stands as a complex phenomenon, often investigated by disciplines that do not conversate with each other (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2022). In the organisational behaviour (OB) literature, employee voice refers to discretionary behaviours, which manifests itself in face-to-face contexts through direct informal voice; in human resource management (HRM) literature, scholars refer to voice as formal expressions, distinguished in indirect and direct voice (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2016; Mowbray, Wilkinson, & Tse, Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015); finally, in the industrial relations (IR) field, voice is seen from a collective point of view to represent employees' interests (Freeman & Medoff, Reference Freeman and Medoff1984).

The growing interest in the study of employee voice has culminated in a compartmentalised and exponential growth of publications, themes, and debates (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2022; Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). The fragmentation of the literature, based on different conceptualisations and related focus, makes the conversation between the disciplines difficult, failing thus to develop a broad research agenda and practical contributions due to the partial vision of the entire story on voice. Consequently, research fails to support organisations in hearing employee voices and benefit from these in decision improvement and organisational innovation (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2016; Wilkinson, Gollan, Kalfa, & Xu, Reference Wilkinson, Gollan, Kalfa and Xu2018). In addition, employee voice is critical for overcoming problems in organisations (Morrison, Reference Morrison2014), and could be vital to manage the current phenomena and the challenges for organisations (Cohen & Roeske-Zummer, Reference Cohen and Roeske-Zummer2021; Hodge, Reference Hodge2022), such as the great resignation, the trend of voluntary and mass employees' resignation from their jobs (Curtis, Reference Curtis2021), or the quiet quitting, where employees fulfil their job duties without subscribing to ‘work is life’ culture to guide their career and development (Warrick & Cady, Reference Warrick and Cady2022).

With our study we aim to answer the call for the need for systematisation of the bodies of literature that investigated employee voice, by adopting a holistic approach that integrates separate and diverse scholarly contributions (Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). To answer this call, the article offers a systematic review of the employee voice literature through the application of complementary bibliometric investigation, which supports the systematisation and integration of previous studies to advance our knowledge of employee voice. We differentiate from preceding reviews on the subject (Bashshur & Oc, Reference Bashshur and Oc2015; Klaas, Olson-Buchanan, & Ward, Reference Klaas, Olson-Buchanan and Ward2012; Mowbray, Wilkinson, & Tse, Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015) by adopting the contemporary approach to reviewing literature through bibliometric methods, which have contributed to connecting multiple streams of research so far treated separately.

This study provides methodological, theoretical and practical contributions. First, the method adopted for reviewing the literature improves rigour and allows for in-depth review. Complementing the systematic literature review method with the quantitative bibliometric analysis enables mapping the field's knowledge structure (Dabić, Maley, Dana, Novak, Pellegrini, & Caputo, Reference Dabić, Maley, Dana, Novak, Pellegrini and Caputo2020; Zupic & Cater, Reference Zupic and Cater2015). Indeed, the bibliometric method offers a systematic and impartial way to structure literature reviews, allowing us to complement and update Bashshur & Oc (Reference Bashshur and Oc2015); Klaas, Olson-Buchanan, and Ward (Reference Klaas, Olson-Buchanan and Ward2012) and Mowbray, Wilkinson, and Tse (Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015) which focused on a broader field of voice. We thus contribute to the HRM, IR and OB literatures by bridging them together in a systematic way to offer a wider perspective of employee voice for research and practice. As concerns the second contribution of our research, we clarify and offer a systematisation of employee voice by identifying thematic clusters over three different research periods. Our work addresses the problem of fragmentation by sorting the phenomena into well-distinguished and manageable types or categories in support of an agenda for future research that calls for the integration of multiple disciplines to understand and investigate employee voice thoroughly. In this regard, based on the results of the systematic review, the third contribution offers a roadmap that shows the progressive development of the conceptualisation of employee voice. By doing this, we examine the paths of employee voice literature, identifying the connections between the different perspectives. Consequently, we contribute to the theoretical advancement of the field by developing a research agenda to bring forward the study of employee voice. Finally, our discussion leads us to propose relevant issues for scholars as well as some practical implications for any kind of organisations and, in particular, for international ones, to allow them to benefit from the contributions of their members. Next section introduces the method used for both the bibliometric and systematic literature review.

Research design

To provide a comprehensive map of the knowledge structure of the literature on employee voice, consistent with recent trends in bibliometric research (e.g., Ayoko, Caputo, & Mendy, Reference Ayoko, Caputo and Mendy2021), we used several complementary bibliometric analyses (Caputo, Pizzi, Pellegrini, & Dabić, Reference Caputo, Pizzi, Pellegrini and Dabić2021) based on a database search that followed the systematic review protocol (Gervasi, Faldetta, Pellegrini, & Maley, Reference Gervasi, Faldetta, Pellegrini and Maley2022; Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, Reference Tranfield, Denyer and Smart2003).

Method

We aimed to select papers based on the best relevance in terms of quality rating and influential capacity (Figure 1) to map the current research. Following established practices (Baker, Pandey, Kumar, & Haldar, Reference Baker, Pandey, Kumar and Haldar2020; Sassetti, Marzi, Cavaliere, & Ciappei, Reference Sassetti, Marzi, Cavaliere and Ciappei2018), the first step concerned a comprehensive search using the Web of Science (WoS) Social Science Citation Index database, business and management subject area. Then we intersected with the 2021 Academic Journal Guide chartered by the Association of Business Schools (ABS) and, to seek relevant documents, we focus on the quality of references by selecting only articles published in journals ranked 3 and above to assure the best relevance of the documents also in terms of quality rating and influential capacity (Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero, & Mas-Machuca, Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; George, Karna, & Sud, Reference George, Karna and Sud2022). We adopted an iterative process to select the keywords for the search string in WoS platform, cross-validating results with Scopus. The best string resulted from having only the keyword ‘voice’ to obtain the broadest possible coverage. The first author performed the initial search at the end of February 2020 and the second search in March 2020. The search found 807 articles in WoS, compared with 779 from Scopus, ranging from 1985 until 2019.

Fig. 1. Methodological process.

In the second step, we defined the inclusion/exclusion criteria based on the relevance of the content of the articles. In our analysis, we decided to include all the documents that respect the definition of employee voice provided by Kwon and Farndale (Reference Kwon and Farndale2020): ‘an employee behaviour aimed at suggesting organisational improvement and/or raising complaints or dissatisfaction about work-related issues through either formal or informal voice channels’. The whole team of researchers then manually selected documents to include in the analysis following the agreed-upon criteria. To ensure the best fit with the definition proposed above and preserve the process from individual biases or errors, the researchers confronted the different versions of the data set, discussing and solving any disagreements about the composition of the final data set. Some borderline cases required the researchers to intensely read the article because there was no definitive decision about inclusion/exclusion. More in detail, the assessment of the title, abstract and keywords was not enough for some articles to make a decision; other cases required a confrontation between researchers about the decision since there was no final agreement. By reading the full text for these cases to determine their relevance, the researchers thus assessed the extent to which the full text dedicated attention to voice conceptualisation and implications discussion for research and practice.

In addition, the primary and most common motivations for exclusion were related to the lack of coherence according to the definition adopted and the absence of focus on our topic of interest in the text. More in detail, as we noted above, the keyword adopted allowed the best coverage in search results leading, at the same time, led to the presence in the data set of some articles focused on different topics, such as organisational, political and strategic issues (Humphrey & Ashforth, Reference Humphrey and Ashforth2000; Piderit, Reference Piderit2000), and discrimination debate (Goltz, Reference Goltz2005), which involved a different concept of voice than our research. Other articles adopted the analysis of the human voice for various research purposes (Backhaus, Meyer, & Stockert, Reference Backhaus, Meyer and Stockert1985; DeGroot & Motowidlo, Reference DeGroot and Motowidlo1999); others indicated voice as a dimension of organisational justice, but from a deeper reading of the text emerged a lack of focus and contribution to voice literature (Husted & Folger, Reference Husted and Folger2004; van den Bos, Reference van den Bos2002). However, we excluded those articles that, based on the in-depth reading of the text content, revealed the absence of focus on the concept of voice and exploration of the related implications. In the end, the final data set was composed of 470 documents.

The third step regarded the pre-processing phase with a data set treatment for data cleaning (e.g., solving inconsistencies, such as homogenising names, titles and keywords,) using Notepad++ and Bibexcel (Persson, Danell, & Schneider, Reference Persson, Danell and Schneider2009). This activity was essential to ensure consistency in the data used to perform the bibliometric analysis (Andersen, Reference Andersen2019). More in detail, authors, journals and references appeared in various forms in the articles examined. For example, for the references by the author LePine JA, two different forms of the name were present (LePine, Jeffrey A. and LePine, J. A.), which caused two cited references; therefore, they were corrected and homogenised. In a similar way, abbreviations of titles in the cited references and different labels of cited journals were corrected. Finally, missing and not captured values by WoS were manually added.

The fourth step concerned the identification of the most important articles to include in the review by a complete bibliometric analysis of the field. The bibliometric analysis entailed: first, the study of the trends in publication, which led us to identify the three periods of evolution based on the criteria described in the following section; second, the keyword co-occurrence analysis, which offers an overview of the employee voice field, with topics of interest located with others; third, the bibliographic coupling of three equal periods to identify the knowledge structure of the field and the most important papers for the systematic review. In this research, bibliographic coupling and keyword co-occurrence complement each other: the former approach identifies the recent topics investigated; the latter approach enriches the thematic interpretation of the results derived from the bibliographic coupling of each period (Andersen, Reference Andersen2019; Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey, & Lim, Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). At the end of this process, 165 articles were selected for the systematic literature based on the visualisation maps and the link strength indexes. The fifth step concerned the systematic review of the essential articles previously identified (Elsbach & van Knippenberg, Reference Elsbach and van Knippenberg2020; Rojon, Okupe, & McDowall, Reference Rojon, Okupe and McDowall2021), which led to the determination of thematic clusters, extensively discussed in the results section. Table 1 summarises the number of articles included per historical period and for each cluster first in the bibliometric analysis and then in the systematic review.

Table 1. Number of articles included in historical periods, clusters, bibliometric analysis and systematic review

At the end of the process, in step 6, we systematised the results regarding the progressive development of the conceptualisation of employee voice, and we fleshed out a knowledge map to provide conceptual clarity and future research directions. Based on this map shown in Figure 6, we examine the paths of employee voice literature within and over the evolution of periods, identifying the connections between the different perspectives and the dominance and influence which occurred in the research on employee voice. Then, we propose relevant issues for scholars as well as some practical implications for organisations. Finally, we summarised the main topics that emerged from our results and the consequent implications for future research based on Gervasi et al. (Reference Gervasi, Faldetta, Pellegrini and Maley2022) and Pellegrini, Ciampi, Marzi, and Orlando (Reference Pellegrini, Ciampi, Marzi and Orlando2020).

Description of the bibliometric analyses

Bibliographic coupling is a bibliometric technique that finds links of strength according to a similarity algorithm. In doing this, it allows mapping the current research on field-based references shared between two documents (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2014), according to which the more reference lists are similar, the stronger the connection between two documents (Zupic & Cater, Reference Zupic and Cater2015). It reveals the best results when it concerns articles referred to a limited period, as citation patterns change over time (Andersen, Reference Andersen2019; Sassetti et al., Reference Sassetti, Marzi, Cavaliere and Ciappei2018). A first analysis of the evolution of research over time by the number of publications per year (Figure 2) indicated the existence of different periods of development. A deeper investigation led us to identify the year 1998 as the first turning point, where research on voice starts to grow significantly compared to previous years (Figure 2). The year 1998 coincides with the publication of Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998), which is the most cited paper in our data set, and that several studies are considered as the foundation study for the field (Barnett, Henriques, & Husted, Reference Barnett, Henriques and Husted2020; Danvila-del-Valle, Estévez-Mendoza, & Lara, Reference Danvila-del-Valle, Estévez-Mendoza and Lara2019). Having identified the first turning point, we followed the established methodological prescription of dividing in equal timeframes of 10 years each (Barnett, Henriques, & Husted, Reference Barnett, Henriques and Husted2020; Castillo-Vergara, Alvarez-Marin, & Placencio-Hidalgo, Reference Castillo-Vergara, Alvarez-Marin and Placencio-Hidalgo2018; Wilden, Hohberger, Devinney, & Lumineau, Reference Wilden, Hohberger, Devinney and Lumineau2019).

Fig. 2. Publication trend in employee voice most relevant literature between 1985 and 2019.

The bibliometric analyses were then performed separately for each period with the software VOSviewer following Van Eck and Waltman (Reference Van Eck and Waltman2014). VOSviewer uses a specific algorithm to determine the clusters ensuring no overlapping articles in more than one cluster. To construct the map, starting from a co-occurrence matrix, VOSviewer calculates a similarity matrix. The process locates items with high similarity close to each other. Then the solution map is translated, rotated and reflected to ensure consistent results (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010).

VOSviewer makes it possible to create and visualise maps working on network data and provides distance-based visualisations of bibliometric networks indicating the relatedness of the nodes. Each node is a circle of the map and is related to the content of the analysis; for instance, in keyword co-occurrence analysis, each circle of the visualisation map represents a keyword, and its size is related to the number of occurrences in the database. Similarly, in the bibliographic coupling visualisation map, each circle is a document of the database, and the size of the circle is related to the strengths of the link based on shared references that it has with other circles: the more links a document has, the larger the size of the circle. The distance between the two circles shows the similarity of references (Sassetti et al., Reference Sassetti, Marzi, Cavaliere and Ciappei2018; Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2014).

We also ran the keyword co-occurrence analysis to identify the topics of research and their relatedness to complement the identification of the conceptual network structure of each period (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010). The visualisation map of the keywords proposes different conceptual clusters that are useful to support the researcher in the systematic review; nevertheless, there can be some overlaps between the keyword clusters with different coupling clusters. This is because keywords and themes are related to each other in the literature, for example, articles in two different clusters might correspond to the same keyword cluster. Similarly, a coupling cluster could be associated with keywords belonging to different clusters (Andersen, Reference Andersen2019).

One of the weaknesses of keyword co-occurrence analysis is related to multiple meanings that a word may be given in a paper (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2014; Zupic & Cater, Reference Zupic and Cater2015). Therefore, we adopted WoS KeyWords Plus®, which ensures consistency in classifying keywords (Caputo et al., Reference Caputo, Pizzi, Pellegrini and Dabić2021). Analysing through multiple bibliometric tools makes it possible to reduce the individual bias of the single method while ensuring a complete picture (Andersen, Reference Andersen2019; Zha, Melewar, Foroudi, & Jin, Reference Zha, Melewar, Foroudi and Jin2020).

Results

This section presents the results of the bibliometric analysis and the systematic literature review for each of the three time periods.

Analysing the publications trends allows us to obtain a picture of the evolution of employee voice studies (Figure 2). According to the criteria described above, the first period starts from 1986 to 1997 and is characterised by limited research activity. The second period refers to 1998–2008; research activity increases with some continuity. The third period begins in 2009 and is characterised by an acceleration of scientific activity, indicating an increasing development of employee voice research.

1986–1997, the foundation: the IR perspective

The first period includes 28 articles. Our review suggests that there was not yet a clear definition of employee voice, rather, it is embedded in IR debating, essentially the labour line of institutional economics and focused on covering all the sides of employment relationship (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2006). With its roots in trade unionism and collective bargaining, voice and representation mostly coincide within IR literature, which strives to bring basic democratic practices within organisations through the law, ensuring opportunities for participation and representation for workplace decisions, and the employees' interest protection in the resolution of workplace disputes and organisational justice (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2006; Wilkinson, Dundon, Donaghey, & Freeman, Reference Wilkinson, Dundon, Donaghey, Freeman, Wilkinson, Donaghey, Dundon and Freeman2020). It is possible to identify this dominant focus from Figure 3a, where the main terms frequently occurring are ‘participation’, ‘voice’, ‘unions’, ‘justice’ and ‘performance’, along with other keywords such as ‘psychological contract’, ‘employee representation’ and ‘conflict’. In addition, the keyword co-occurrence results demonstrated that the term ‘voice’ is not the most connected. Indeed, it is interesting to note that the centre of the figure is dominated by the term ‘participation’ that is connected to almost all keywords of the map, differently by ‘voice’ that lacks connections with the terms positioned on the right of the figure, such as ‘boards’, ‘unions’ and ‘employee representation’.

Fig. 3. (a) Keywords co-occurrence map of the first period (1986–1997). (b) Bibliographic coupling map of the first period (1986–1997).

Based on the above, we deepen how the IR purposes trace the direction of employee voice research in exploring these arguments.

The workers' representation and labour–management relationship is the red cluster of Figure 3b, which we associated to the red cluster of keywords co-occurrence, including terms such as ‘boards’, ‘unions’ and ‘employee representation’. The articles of this group follow the collective conception of voice by focusing on the institutions for worker representation in the workplace decisions and their impact on organisational outcomes (Kleiner & Lee, Reference Kleiner and Lee1997; Miller & Mulvey, Reference Miller and Mulvey1991), and the labour–management relationship (Godard, Reference Godard1992; Kennedy, Drago, Sloan, & Wooden, Reference Kennedy, Drago, Sloan and Wooden1994).

The most relevant article of this group in terms of the highest link strength to other studies is Boroff and Lewin (Reference Boroff and Lewin1997). Their results strongly conclude that loyal employees who experienced unfair workplace treatment ‘suffer in silence’ (Boroff & Lewin, Reference Boroff and Lewin1997: 60) rather than exercise voice. The empirical validity of the exit/voice model in different national labour markets with special attention to unionism is the focus of most of the articles of this group. For instance, Leigh (Reference Leigh1986) focused on the USA, Miller and Mulvey (Reference Miller and Mulvey1991) and Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Drago, Sloan and Wooden1994) focused on the Australian context, and Kleiner and Lee (Reference Kleiner and Lee1997) reported evidence from South Korea. Keeping the focus on collective voice, Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Drago, Sloan and Wooden1994) paid close attention to the effective activity of unions in the workplace in terms of bargaining with management over training. Finally, Kleiner and Lee (Reference Kleiner and Lee1997) showed that voice in work councils and unions impacts HRM practices such as wages, turnover, employee satisfaction and labour productivity. The study of Olson-Buchanan (Reference Olson-Buchanan1996) assumed a central position. It is among the first to link distinct pieces of literature, going through research and theory of industrial–organisational psychology with social psychology and procedural justice.

Employee voice as an organisational fairness instrument cluster (Figure 3b, green) denotes a fundamental and common research interest in decision-making, which frames voice as a form of subordinate participation (Korsgaard & Roberson, Reference Korsgaard and Roberson1995: 658) and instrument that ensures the fairness of the process (Goodwin & Ross, Reference Goodwin and Ross1992; Magner, Welker, & Johnson, Reference Magner, Welker and Johnson1996). Indeed, the ‘justice’ keyword stands out on the map. We adopted this term in the co-occurrence analysis as an umbrella term covering related words, such as perceived fairness, equity and specific types of organisational justice, e.g., procedural justice, which relate to the other keywords of the map.

Specifically, Korsgaard, Schweiger, and Sapienza (Reference Korsgaard, Schweiger and Sapienza1995) emerge in this group for the highest power of link strength, denoting the relevance of this study for the contribution to research in this first period: voice can be a useful instrument to enhance perceptions of the fairness of the decision-making process. In this line, Korsgaard and Roberson (Reference Korsgaard and Roberson1995) propose two perspectives of voice conception: one considers voice regardless of the effective influence over the decision, indicated as non-instrumental voice; the other evaluates employee voice related to the effective impact on a decision via indirect influence, i.e., instrumental voice. This perspective of analysis shows some initial results of employee voice about the possible consideration of it as a multidimensional construct in terms of suitability to different purposes of analysis, as voice impacts employees' justice perception of fairness and also influences employees' attitudes, such as the intention to quit (Daly & Geyer, Reference Daly and Geyer1994).

The Exit-Voice-Loyalty (EVL) framework cluster (Figure 3b, yellow) is motivated by a strong focus on the EVL framework proposed by Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) and the following authors, as demonstrated by keywords such as ‘satisfaction’, ‘exit’ and ‘neglect’ (Figure 3a). Despite Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) being a source not included in our data set, the papers discussed in our review reveal and confirm the critical role of this book for employee voice research.

Two articles present the highest total link strength: Withey and Cooper (Reference Withey and Cooper1989) and Spencer (Reference Spencer1986). Withey and Cooper (Reference Withey and Cooper1989) are central to the figure, and their study investigates employees' dissatisfaction responses in terms of exit, voice, loyalty and neglect. The study of Spencer (Reference Spencer1986) focused on the relationship between the availability and quality of a certain number of formal voice mechanisms and voluntary turnover as an exit variable. In doing so, the author considers the presence of unions in the workplace and demonstrates that the availability of multiple voice mechanisms influences employees' retention, suggesting some additional insights into the Exit-Voice-Loyalty-Neglect (EVLN) framework.

This line of research is also found in Mayes and Ganster (Reference Mayes and Ganster1988), who found that two of the constructs of Hirschman's framework (voice and exit) are independent reactions not mutually exclusive and impact individually on organisational turnover rates. Keeley and Graham (Reference Keeley and Graham1991) also proposed normative implications of Hirschman's framework EVL, providing clearer guidance concerning how much voice or exit is appropriate under different circumstances.

Employee voice in HRM (the beginning) cluster (Figure 3b, blue) appears more detached from the previous ones, and this could be because it introduces employee voice in organisations from another point of view, that is HRM practices applied to the workplace to increase the organisational performance. Indeed, another important keyword in this period that denotes the emerging of HRM perspective is ‘performance’ (Figure 3a).

In a non-union context (Feuille & Chachere, Reference Feuille and Chachere1995), different mechanisms need to be implemented to allow employees to voice their opinion and participate in organisational decision-making about their work. Lewin and Mitchell (Reference Lewin and Mitchell1992) is the study that connects this stream with the others. In their article, the authors examined the different voice systems available for organisations. Taking into account unionised and non-unionised settings, the characteristics of mandated voice systems and ‘voluntary’ voice systems affect employee turnover and increase intermittent employment. Feuille and Chachere (Reference Feuille and Chachere1995) tried to understand the conditions under which employers make formal mechanisms available in organisations for those employees not represented by unions, referring to the justice function of employee voice. The study finds that the more value attributed to human resource in the workplace and the greater the number of employee-oriented HR practices, the more formal non-union grievance procedures are implemented. In this vein, McCabe and Lewin's (Reference McCabe and Lewin1992) conceptual paper shows that the importance of employee voice for non-unionised organisations aside from the primary purpose of providing this voice mechanism to employees is related to avoiding unions; and this impacts the decision of some organisations to make grievance procedures available. The contribution of Aaron (Reference Aaron1992), at the edge of the cluster, provides the legal perspective of employee voice when manifested through a non-union mechanism. The article highlights a limited function of non-union voice in a system legally based on union protection.

1998–2008: the raising of OB and the development of HRM perspective

The beginning of the second period, 1998, coincides with the publication of the most relevant article on employee voice, Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998), with more than 170 citations among all the documents included in the data set. These authors introduced the first definition of voice to the OB literature and developed an operational measure to investigate it. They defined employee voice as ‘a promotive behaviour that emphasises the expression of constructive challenge intended to improve rather than merely criticise’ (p. 110). Most recent authors of voice research consider this formal definition of voice and operational measure provided by Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998) as the starting point of voice research in OB literature (Morrison, Reference Morrison2011; Mowbray, Wilkinson, & Tse, Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015; Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). OB represents the dominant perspective during this second analysis period, which considers voice as a discretionary and improvement-oriented behaviour (Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007) and focuses on micro-level factors affecting voice behaviours by investigating it at the individual level. The individual level of analysis in the OB-centric perspective is also the focus of voice studies in the HRM field, which in this second period starts to profoundly investigate the interplay between non-union and union representation structures and the impact on employee attitudes towards organisations (Batt, Colvin, & Keefe, Reference Batt, Colvin and Keefe2002; Bryson, Reference Bryson2004; Gollan, Reference Gollan2006). Moreover, this period includes other articles in the top 10 most cited documents of the entire database (Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998; Milliken, Morrison, & Hewlin, Reference Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin2003). Therefore, we argue that this period is the most important in terms of research because it contains the core foundations of what employee voice research is nowadays.

Employee voice as a distinct OCB behaviour cluster of studies (Figure 4b, green) catches the eye for the central position and the presence of the most important articles of the period. It shows the central importance of OB, which found evidence in cluster green of Figure 4a, revealing keywords such as ‘OCB’ and ‘extra-role behaviour’. Moreover, other keywords of this cluster, such as ‘personality’, ‘SET’ (social exchange theory), illuminate about the aspects investigated by the articles included in this group of documents. Studies in this cluster focus on identifying and validating different types of OBs and seek to identify antecedents of speaking up in the workplace (Burris, Detert, & Chiaburu, Reference Burris, Detert and Chiaburu2008; Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998). Exploring these research interests, we can identify an initial leading line of inquiry that explores voice along with other types of OCB (Organisational Citizenship Behaviour) affiliative and proactive behaviours, such as helping behaviours (LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998; Stamper & Dyne, Reference Stamper and Dyne2001; Zhou & George, Reference Zhou and George2001) and taking charge (Morrison & Phelps, Reference Morrison and Phelps1999). It assumes an integrative explanation that takes into consideration situational factors involving broader feelings of employees towards the organisation (Stamper & Dyne, Reference Stamper and Dyne2001), leadership antecedents to voice, such as openness (Burris, Detert, & Chiaburu, Reference Burris, Detert and Chiaburu2008; Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Morrison & Phelps, Reference Morrison and Phelps1999) and person-centred antecedents, such as self-esteem (LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne1998), and personality traits (LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne2001).

Fig. 4. (a) Keywords map in the voice field of research (five co-occurrence at least) during the second period 1998–2008. (b) Bibliographic coupling of articles included in the second period 1998–2008.

Detert and Burris (Reference Detert and Burris2007) emerge among the most cited documents within the data set documents. These authors consider differences in employees in terms of proactivity and satisfaction, highlighting the importance of positive leader behaviours associated with creating a safe workplace that impact on employees' voice. In this sense, Morrison and Phelps (Reference Morrison and Phelps1999), reviewing OCB literature and extra-role, differentiate taking charge from other proactive behaviours, including voice. Individual personality traits are additionally relevant. This line of research is followed by LePine and Van Dyne (Reference LePine and Van Dyne2001), assessing the relationship between individual differences (personality and cognitive ability) and specific behaviours such as voice, cooperative behaviour and task performance. Burris, Detert, and Chiaburu (Reference Burris, Detert and Chiaburu2008) focused on the influence of employee psychological state, related to attachment to the organisation, on employees' motivation to speak to the supervisor. The study reveals the importance of leadership style and the quality of the relationship between leader and follower for employee perceptions, and finds that exit responses related to the EVLN framework can occur formally and through a detached state that inhibits voice behaviours. This framework represents the main topic investigated in the closest cluster (yellow).

Employee voice and EVL theory cluster (Figure 4b, yellow) contains 13 articles denoting the predominant theoretical perspective that stands out in most of the voice publications about the EVL framework by Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970) and following development (Farrell, Reference Farrell1983). Similarly to the keyword co-occurrence map of the previous period, in the yellow cluster of Figure 4a keywords emerge such as ‘satisfaction’, ‘responses’, ‘loyalty’, ‘exit’ and ‘neglect’, which are the main elements of the EVL framework. More in detail, the systematic review of articles of this cluster suggests that ‘satisfaction’ is addressed involving multiple aspects (Hagedoorn, Van Yperen, Van De Vliert, & Buunk, Reference Hagedoorn, Van Yperen, Van De Vliert and Buunk1999), such as psychological contract violation (Turnley & Feldman, Reference Turnley and Feldman1999, Reference Turnley and Feldman2000), job insecurity (Sverke & Goslinga, Reference Sverke and Goslinga2003; Sverke & Hellgren, Reference Sverke and Hellgren2001) and specific dimensions of commitment (Luchak, Reference Luchak2003; Sverke & Hellgren, Reference Sverke and Hellgren2001). In this vein, two lines of research appear. The first line includes articles that consider situational factors, such as job-related, organisational attributes and individual differences, to explore possible responses to dissatisfaction based on the theoretical framework (Hagedoorn et al., Reference Hagedoorn, Van Yperen, Van De Vliert and Buunk1999; Mishra & Spreitzer, Reference Mishra and Spreitzer1998; Turnley & Feldman, Reference Turnley and Feldman1999). Mishra and Spreitzer (Reference Mishra and Spreitzer1998) is this cluster's most coupled article. These authors adopt the EVLN framework to outline the different responses that employees manifest to downsizing according to their stress-based model, integrating the influence of fairness and justice on survivor responses. Following this line, the second relevant paper of this subgroup is Turnley and Feldman (Reference Turnley and Feldman1999), which shows an empirical study of situational factors and justice dimensions that explain different employee responses to violation of the psychological contract. The second line of research includes articles mainly published in IR journals that consider forms of collective voice to cope with uncertain employment situations and explore the consequences for organisations regarding turnover and exit (Sverke & Goslinga, Reference Sverke and Goslinga2003; Sverke & Hellgren, Reference Sverke and Hellgren2001). In particular, Sverke and Goslinga (Reference Sverke and Goslinga2003) focused on job insecurity and found that dissatisfying employment conditions are primarily related to exit and loyalty reactions, but not to the use of voice in terms of union participation.

Employee voice as an organisational and human resource practices cluster of studies (Figure 4b, red) starts the integration between IR and HRM, particularly examining the interplay between non-union and union representation arrangements and the impact on employee perceptions, attitudes and performance. This cluster's line of research seems to focus on analysing the impact of alternative IR institutions, along with more direct forms of voice and HRM theories and practices. We associated ‘commitment’, ‘job aspects’ and ‘turnover’ keywords to this cluster (Figure 4a).

Gollan (Reference Gollan2006) is the most relevant article regarding connecting strength. Focusing on the effectiveness of union and non-union voice arrangements in the British context, the author highlighted that the complementary presence of both trade unions and direct voice mechanisms benefits employees by providing multiple channels for voice. The second relevant paper of this cluster is by Dundon and Gollan (Reference Dundon and Gollan2007), which focused on the conceptual analysis of the literature on voice mechanism and the conditions that influence the forms of voice present in the workplace. Findings revealed a tendency in British workplaces to replace traditional single union voice with multiple non-union voice arrangements. The study of the unions–HRM link is the research interest of Wood and Wall (Reference Wood and Wall2007), who frame employee voice among high commitment management practices, and of Batt, Colvin, and Keefe (Reference Batt, Colvin and Keefe2002) and Bryson (Reference Bryson2004), who are focused on the effectiveness of voice mechanisms in benefitting employees and on the impact that voice has on HRM practices for organisational and employee outcomes such as quit rates and intentions to exit.

Employee voice as a perception of organisational fairness cluster of studies (Figure 4b, blue) completes the picture of the period, and focuses on organisational justice literature as shown by the related keyword ‘justice’ (Figure 4a). Voice influence individuals' evaluations of the fairness of processes and practices implemented by organisations (De Cremer, Reference De Cremer2006; Kernan & Hanges, Reference Kernan and Hanges2002). The most linked document of this cluster is De Cremer (Reference De Cremer2006), about the influence of procedural justice with leadership styles on two affective responses. The authors employed voice as an instrument to manipulate procedural justice perceptions, which refers to having a voice in decision procedures or not, highlighting that it impacts followers' emotional reactions. Kernan and Hanges (Reference Kernan and Hanges2002) is the second relevant article of this group; it finds voice to be a way to enhance perceptions of procedural fairness, developing a comprehensive model of survivor reactions to a reorganisation. Another relevant study is by Lind and van den Bos (Reference van den Bos2002), who developed the uncertainty management theory of fairness indicating that ‘Voice, when included as an element of decision-making procedures, is one of the most powerful ways to engender judgments that the decision making process is fair’ (Lind & van den Bos, Reference Lind and van den Bos2002: 186).

2009–2019: the integration of IR, OB and HRM perspective

The last identified period involves 340 contributions in the bibliometric analysis. There are relevant attempts to integrate different management fields during this period and thus to overcome the ‘silo’ approach to studying voice. A more integrative conceptualisation of voice emerges and covers IR, HRM and OB perspectives. It defines voice as ‘all of the ways and means through which employees attempt to have a say about, and influence, their work and the functioning of their organisation’ (Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). Keyword co-occurrence results are in line with this integrative approach of voice research. The articles included in this period have produced above 1500 keywords. From Figure 5a, it is possible to note an increased integration of the previously disparate topics, which confirms the establishment of the development of research that looks at employee voice from 360 degrees.

Fig. 5. (a) Keywords map in the voice field of research during the third period (2009–2019). Eight co-occurrences at least. (b) Bibliographic coupling of articles included in the third period (2009–2019).

The integration of voice perspectives cluster of studies (Figure 5b, red) is the most numerous in terms of articles, which are mainly oriented towards the study of employee engagement (Kwon, Farndale, & Park, Reference Kwon, Farndale and Park2016; Marchington & Suter, Reference Marchington and Suter2013; Rees, Alfes, & Gatenby, Reference Rees, Alfes and Gatenby2013) and satisfaction (Holland, Pyman, Cooper, & Teicher, Reference Holland, Pyman, Cooper and Teicher2011; Laroche, Reference Laroche2017). The primary focus is rooted in the HRM field, and many studies denote more or less direct integrations with other fields of literature (Avgar, Sadler, Clark, & Chung, Reference Avgar, Sadler, Clark and Chung2016; Laroche, Reference Laroche2017; Marsden, Reference Marsden2013). The most connected article of this cluster for total link strength is Pohler and Luchak (Reference Pohler and Luchak2014), who integrate IR with HRM and OB. Specifically, focusing on high-involvement work practices and unions, this study highlights the importance of both individual and collective voice mechanisms in organisations, which balance the potential effects of the interests of management and unions to create more efficiency, equity and voice.

Mowbray Wilkinson, and Tse (Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015) and Mowbray (Reference Mowbray2018) represent the second and third relevant articles of this cluster resulting from the bibliographic coupling and present two integrative studies about literature on employee voice. Mowbray, Wilkinson, and Tse (Reference Mowbray, Wilkinson and Tse2015) propose an integrative review that considers IR literature and the labour economics literature relevant to the HRM literature, thus connecting them as a unique discipline labelled HRM/ER. Mowbray (Reference Mowbray2018) extends the attention on managers and presents a qualitative case study that integrates HRM/ER and OB definitions and shows that the lessened power of role influences the creation of informal voice channels.

Employee voice and performance: the role of leaders cluster (Figure 5b, blue) is rooted in the OB research field and follows the line drawn by the most cited article, that of Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998), about the investigation of the impact of employee voice and multiple extra-role proactive behaviours on performance.

The most relevant study of this cluster is the meta-analysis provided by Chamberlin, Newton, and Lepine (Reference Chamberlin, Newton and Lepine2017), which clarifies the concept of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms and develops a theoretical framework considering the antecedents and consequences of these forms. The most important results of this study are identifying variables recognised as antecedents of voice, e.g., personal attributes, leadership and contextual factors; and psychological states of felt responsibility and engagement as the underlying mechanisms through which these variables impact performance (Chamberlin, Newton, & Lepine, Reference Chamberlin, Newton and Lepine2017). The second relevant article was published 5 years earlier: Tornau and Frese (Reference Tornau and Frese2013) developed a meta-analysis to clarify the similarities and differences between four proactivity constructs (proactive personality, personal initiative, voice and taking charge), identifying those related to personality and those related to behaviour. One of the main results shows that the proactive behaviours investigated predicted job performance much better than personality, representing also the main basis of the judgment rendered in supervisor reports. Regarding this, a specific trend of this cluster concerns the research attention paid to supervisors (Burris, Reference Burris2012), not only for performance ratings rendered but also for other leadership factors associated with employee voice (Burris, Detert, & Romney, Reference Burris, Detert and Romney2013; Howell, Harrison, Burris, & Detert, Reference Howell, Harrison, Burris and Detert2015; Lloyd, Boer, Keller, & Voelpel, Reference Lloyd, Boer, Keller and Voelpel2015; Weiss, Kolbe, Grote, Spahn, & Grande, Reference Weiss, Kolbe, Grote, Spahn and Grande2018). These studies move the attention of voice research from how employees perceive leaders to how leaders communicate with their followers and manage judgments about who speaks up (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Kolbe, Grote, Spahn and Grande2018). Among the most recent and relevant, Howell et al. (Reference Howell, Harrison, Burris and Detert2015) showed that managers systematically evaluate employee voice contributions based on heuristic and biased processing, influenced by employees' membership in minority groups or majority groups. Following this line, the empirical study of Fast, Burris, and Bartel (Reference Fast, Burris and Bartel2014) showed that low managerial self-efficacy triggers a defensive stance towards employee voice, reducing voice solicitation and implementation of suggestions and increasing the tendency to discriminate against employees who speak up.

Moreover, Burris (Reference Burris2012) showed that managerial responses to followers' voice depended on the type of voice exhibited: less proactive forms of voice that support the status quo and don't challenge it generate more favourable reactions from managers. Finally, Weiss et al. (Reference Weiss, Kolbe, Grote, Spahn and Grande2018) show that inclusive leader language stimulates followers' voice, depending on their professional group membership.

The importance of leadership style and culture for employee voice cluster (Figure 5b, green) keeps the focus on OB and mainly on leadership styles and social relations, focusing on the culture and national context. Many of the articles in this group concern China-based field studies (Bai, Lin, & Liu, Reference Bai, Lin and Liu2019; Kong, Huang, Liu, & Zhao, Reference Kong, Huang, Liu and Zhao2016; Xu, Qin, Dust, & DiRenzo, Reference Xu, Qin, Dust and DiRenzo2019), where it emerges either implicitly or more explicitly Confucian-based values that affect leadership. Indeed, leadership keywords refer to concepts such as authority, characterised by moral integrity and fatherly benevolence, influencing organisational characteristics and leadership traits (Zhang, Huai, & Xie, Reference Zhang, Huai and Xie2015; Zhu & Akhtar, Reference Zhu and Akhtar2017).

The most relevant article is by Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Qin, Dust and DiRenzo2019), which highlights the influence of congruence of supervisor–follower as a contextual factor associated with voice and the critical role of leaders in creating a psychological safety environment. Yiwen Zhang, LePine, Buckman, and Wei's (Reference Zhang, LePine, Buckman and Wei2014) study presents additional results about contextual factors, showing the influence of specific leadership behaviours (e.g., transformational leadership). A general theme among these studies is the call of attention to the context in which data are gathered, which may influence the results, as the Chinese context tends to be characterised by high power distance. In a similar approach, moving to the European context, Guenter, Schreurs, van Emmerik, and Sun (Reference Guenter, Schreurs, van Emmerik and Sun2017) investigated the influence of specific types of leaders' behaviours, such as authentic leadership, to stimulate voice behaviour in individuals with low proactivity.

The contextual and social factors affecting voice behaviours cluster of studies (Figure 5b, yellow) is focused on the study of employee voice antecedents that refer to contextual factors and the social exchange relationships of the workplace. This cluster differs from the above in its specific focus on boundary conditions related to leadership affecting voice behaviours rather than on the main effects these elements have on employee voice. Moreover, the focus here is on the unit-level outcomes rather than on the individual level. Starting from the assumption that not all leaders have the resource and the motivation needed to implement suggestions from their employees, McClean, Burris, and Detert (Reference McClean, Burris and Detert2012) provide an empirical analysis to understand the conditions under which employee voice impacts exit, highlighting the importance of managers' responsiveness to voice among groups of employees.

The cluster interestingly includes most of the articles by Thomas Ng. Ng and Feldman (Reference Ng and Feldman2015) show that when organisations allow employees a greater degree of control over employment arrangements based on personal preferences and needs (i.e., ‘idiosyncratic deals’, p. 893), they motivate employees to participate in organisational decisions through voicing their suggestions. Moreover, voice is studied in Ng and Feldman (Reference Ng and Feldman2013) as a behavioural variable to understand the process through which people attribute a sense to social signals, highlighting that employees' perceptions of supervisor embeddedness signal and influence employees' perceptions of organisational trustworthiness and, in turn, affect their relationship with the organisation.

The different forms of employee voice cluster of studies (Figure 5b, purple) represents a new nuance in employee voice research, whereby studies focus on employee voice from a broader perspective. Alternative forms related to voice ranged from actual voice behaviours to whistle-blowing (Kirrane, O'Shea, Buckley, Grazi, & Prout, Reference Kirrane, O'Shea, Buckley, Grazi and Prout2017; Skivenes & Trygstad, Reference Skivenes and Trygstad2010) and silence (Knoll, Hall, & Weigelt, Reference Knoll, Hall and Weigelt2019; Prouska & Psychogios, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2016, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2019). Klaas, Olson-Buchanan, and Ward (Reference Klaas, Olson-Buchanan and Ward2012) provided the first relevant contribution, presenting an integrative review of alternative forms of voice determinants to understand how different processes and factors impact voice behaviour. Considering both unionised and non-unionised organisations, the authors investigate why employees manifest different forms of voice and how leaders' behaviours and organisational practices and policies influence these forms. The second and third relevant articles are by Prouska and Psychogios (Reference Prouska and Psychogios2016) and Prouska and Psychogios (Reference Prouska and Psychogios2019), concerning possible responses of employees in a long-term turbulent economic environment. Aiming to capture employee perceptions of workplace voice during the crisis period, these authors study the other side of the voice coin: silence (Prouska & Psychogios, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2016). These authors then proposed a new study of line managers' experience of employee voice and silence, considering their perspective and organisational position (Prouska & Psychogios, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2019).

Discussion: an agenda for future research

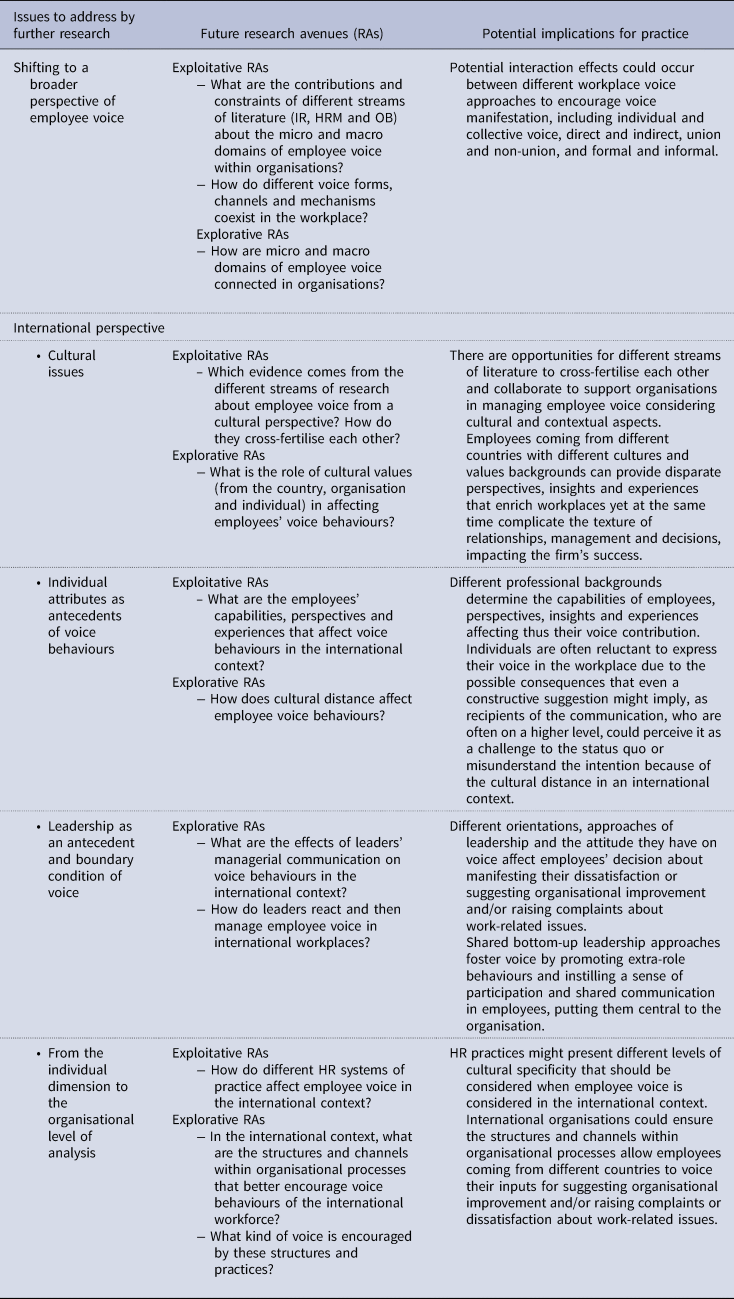

The state of the art of employee voice literature shows that studies are developed in ‘silos’, reducing the possibility of cross-fertilisation and theoretical contamination among researchers (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2022; Bashshur & Oc, Reference Bashshur and Oc2015; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2015; Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). A need thus arises to assume a broader perspective, continuing the integration of different fields and approaching voice from a broad perspective that considers multiple forms for employees to communicate within the organisation their dissatisfaction about work-related issues or their suggestions for organisational improvement (Wilkinson, Barry, & Morrison, Reference Wilkinson, Barry and Morrison2020). Therefore, considering a broader analysis of management perspectives, IR, OB and HRM help delve deeper into employee voice research's specific characteristics. This review shows that recent works adopting this new line of research enlarge the boundaries of interest towards alternative forms of voice such as whistle-blowing (Kirrane et al., Reference Kirrane, O'Shea, Buckley, Grazi and Prout2017; Skivenes & Trygstad, Reference Skivenes and Trygstad2010) and silence (Knoll, Hall, & Weigelt, Reference Knoll, Hall and Weigelt2019; Prouska & Psychogios, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2016, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2019). Moreover, the systematisation of results allows, on the one hand, proposing an integrated framework of the primary intellectual knowledge about the development of employee voice considering the individual perspective (Figure 6), on the other hand, to offer future research directions and the related potential implications for practice (Table 2). In this regard, the next step should be to understand how to translate this critical knowledge of voice into actual improvements for organisational effectiveness. In addition, the findings show that the research about voice mainly focuses on domestic contexts. The relevance suggested by recent research about cultural aspects and the research fronts identified in this work might represent an important starting point for future research on employee voice to support organisations in effectively managing employees in international contexts (Wang & Varma, Reference Wang and Varma2019). The following paragraphs discuss in detail these main findings.

Fig. 6. A framework of the studies on employee voice.

Table 2. Research avenues and potential practical implications on employee voice

From industrial relations to the individual level of voice: what next?

Our analysis underlines that employee voice research experienced a progressive development of the conceptualisation of employee voice (Figure 6) that starts with the predominance of a collective perspective. At the early stage, based on the results of our first period of analysis and as shown in the first quadrant of Figure 6, voice research reveals embedded in the IR perspective regarding broad employment relationships. Through its roots in trade unionism and collective bargaining, IR aims to bring into organisations democratic practices that ensure employees' opportunity for participation and representation in work decisions.

Accordingly, researchers introduced voice in this collective perspective associated with unions as the most powerful form of voice in representing employees' interests (Freeman & Medoff, Reference Freeman and Medoff1984). The IR focus dominates and influences most studies composing the early stage of research on voice. For instance, as shown in Figure 6 – central quadrant of second column – influenced by the more broad intent of protecting employees' interests and giving them the legitimation to participate in decisions, scholars within organisational justice literature refer to voice as the instrument that ensures the fairness of the process through the right to participation (Korsgaard & Roberson, Reference Korsgaard and Roberson1995; Korsgaard, Schweiger, & Sapienza, Reference Korsgaard, Schweiger and Sapienza1995). The justice perspective of voice opens new research directions on employee voice, which starts from the evidence that voice impacts employees' justice perception of fairness and influences employees' attitudes (Daly & Geyer, Reference Daly and Geyer1994). This last line of enquiry encouraged voice research over the years, and scholars have moved from a collective perspective of voice to a more individual level, considering different points of view. First, scholars within the justice literature keep the focus on employee voice as an instrument for managing fairness perceptions about the organisational decision-making process, aiming to investigate its effects on employees' attitudes and behaviours as a priority objective (De Cremer, Reference De Cremer2006; Lind & van den Bos, Reference Lind and van den Bos2002). Second, Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998) introduced voice within the OBs literature by defining it as an extra-role behaviour aimed at organisational improvement. This new conception of voice as individual behaviour that is challenging yet promotive has become widely adopted by OB research. Over the years, scholars have provided relevant contributions about antecedents and consequences of employee voice at the individual level of analysis within this research field. For instance, studies highlighted the influence of individual characteristics and self-beliefs (Kong et al., Reference Kong, Huang, Liu and Zhao2016; LePine & Van Dyne, Reference LePine and Van Dyne2001), the contextual factors affecting the workplace climate and the employee's confidence to speak (Chen & Hou, Reference Chen and Hou2016; Qin, DiRenzo, Xu, & Duan, Reference Qin, DiRenzo, Xu and Duan2014; Song, Wu, & Gu, Reference Song, Wu and Gu2017). Moreover, focusing on employee involvement, studies rooted in the HRM field investigate the possible forms that employee voice behaviour can assume within the organisation by considering voice as a practice to foster commitment, participation and organisational outcomes (Batt, Colvin, & Keefe, Reference Batt, Colvin and Keefe2002; Marchington & Suter, Reference Marchington and Suter2013; Wood & Wall, Reference Wood and Wall2007).

As shown in the third column of Figure 6, the relevant results reached on the individual level of analysis have gradually highlighted the critical relationship between employee voice and the leadership dimension (Bai, Lin, & Liu, Reference Bai, Lin and Liu2019; Detert & Burris, Reference Detert and Burris2007; Fast, Burris, & Bartel, Reference Fast, Burris and Bartel2014; Guenter et al., Reference Guenter, Schreurs, van Emmerik and Sun2017; McClean, Burris, & Detert, Reference McClean, Burris and Detert2012). As shown in the third period of analysis, the research initially considered leaders the main target of voice behaviour. In this view, studies revealed that since leaders exercise an important influence on the implementation of practices and the value of employees' performance (Lebel, Reference Lebel2016; Morrison, Reference Morrison2011), their behaviours and styles influence the relationship with their employees and their perceptions, conditioning also the confidence to speak (Tangirala & Ramanujam, Reference Tangirala and Ramanujam2012; Wu, Zhaoli, Xian, & Zhenyu, Reference Wu, Zhaoli, Xian and Zhenyu2017). Then, the attention to leaders shifted to characteristics and feelings related to their roles as boundary conditions influencing employee voice behaviour because leaders also affect the workplace where employee voice might occur (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Harrison, Burris and Detert2015; Tangirala & Ramanujam, Reference Tangirala and Ramanujam2012).

Based on the above, the present article offers new directions for this research field, highlighting the need to go beyond traditional research interests. Indeed, this systematic literature review results confirm that much has been done regarding the antecedents, boundary conditions and consequences of employee voice at the individual level of analysis. As detailed in Table 2, to move forward, it is necessary to translate this critical knowledge of voice into actual improvements in organisational effectiveness. It emerges that employee voice is an element that HRM needs to know how to manage (Barry & Wilkinson, Reference Barry and Wilkinson2022). At the practical level, the focus on formal and informal voice-based mechanisms is insufficient to encourage voice behaviours; rather, potential interaction effects occur between different approaches for voice (Pohler & Luchak, Reference Pohler and Luchak2014), such as collective/individual, direct/indirect, union and non-union avenues for voice; it is critical, especially in turbulent moments and crises (Prouska & Psychogios, Reference Prouska and Psychogios2019). It follows that a shift to a broader perspective is required, from the individual dimension to the organisational level of analysis, which in turn requires an investigation into the processes and structures consistent with the contextual, individual and cultural factors, which can support employee voice within the organisation that hence benefits from employees' input. As such, the analysis of how micro and macro domains are connected is an important challenge for future studies as described in Table 2.

The context matters: how to manage voice in nowadays workplaces

The organisational context assumes relevance along with factors related to cultural dimensions, as confirmed by the results of this study. Especially during the analysis of the third period, results suggest that the attention of future research should focus more on the role of cultural aspects in affecting organisations and employee voice (Kwon & Farndale, Reference Kwon and Farndale2020; Wang, Baba, Hackett, & Hong, Reference Wang, Baba, Hackett and Hong2019; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Qin, Dust and DiRenzo2019). These reflections are related to the impossibility of finding global solutions for organisation and management problems, which face common basic issues within the organisations due to national cultural differences but respond differently according to each country (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2001).

In this regard, we believe there are opportunities for different streams of literature to cross-fertilise each other and collaborate to explore the cultural and contextual issues in studying employee voice as proposed in table 2. For instance, the different orientation that management can have on employees' input affects the organisational context where employees have to decide to manifest their opinion or not (Kwon & Farndale, Reference Kwon and Farndale2020). It is a critical issue for organisations nowadays, characterised by the increasingly relevant presence of individuals from various cultural contexts. In addition, as noted, the potential contribution of each member expressed through their voice can represent a competitive advantage in acquiring additional knowledge by leveraging the capabilities of employees, perspectives, insights and experiences. These, undoubtedly, are influenced by different cultural values and professional backgrounds (Brewster, Sparrow, & Harris, Reference Brewster, Sparrow and Harris2005; Tröster & van Knippenberg, Reference Tröster and van Knippenberg2012). Indeed, at a practical level, employees coming from different countries with different cultural and professional backgrounds can provide disparate perspectives, insights and experiences that enrich workplaces yet at the same time complicate the texture of relationships, management and decisions, impacting the firm's success (Lam & Mayer, Reference Lam and Mayer2014; Mackenzie, Podsakoff, & Podsakoff, Reference Mackenzie, Podsakoff and Podsakoff2011). A related critical topic for employee voice literature is cultural distance, affecting the willingness of employees to manifest their opinions in the workplace (Jiang, Le, & Gollan, Reference Jiang, Le and Gollan2018; Kwon & Farndale, Reference Kwon and Farndale2020). Individuals are often reluctant to express their voice in the workplace due to the possible consequences that even a constructive suggestion might imply, as recipients of the communication, who are often on a higher level, could perceive it as a challenge to the status quo (Milliken, Morrison, & Hewlin, Reference Milliken, Morrison and Hewlin2003; Morrison, Reference Morrison2011) or misunderstand the intention because of the cultural distance in an international context (Jeung & Yoon, Reference Jeung and Yoon2018).

The above issues are relevant topics for future research on employee voice, which needs to go beyond a country-level focus to understand the main points and implications when the employee voice topic is discussed in the context of international HRM, as proposed in Table 2. In our opinion, the research fronts of voice literature identified in the third period represent a critical avenue for future research that could help organisations manage individuals from different backgrounds and benefit from employee suggestions by implementing effective enhancements.

For this purpose, the global leadership is critical to influence employees' behaviours. Consequently, we need to understand the leaders' managerial communication with subordinates, how leaders evaluate employees' contributions and the impact of leaders' behaviours on follower outcomes in the international context (Jeung & Yoon, Reference Jeung and Yoon2018). Our findings have demonstrated that, over the years, a stable element that attracted research interest is leadership, influencing both employees and their willingness to voice opinions and the context where voice might occur (Jeung & Yoon, Reference Jeung and Yoon2018). Consequently, leadership in nowadays workplace might foster voice by promoting extra-role behaviours and instilling a sense of participation and shared communication in employees, putting them central to the organisation. Therefore, future studies might deeply investigate shared bottom-up leadership approaches (Cheng, Bai, & Hu, Reference Cheng, Bai and Hu2022; Zeier, Plimmer, & Franken, Reference Zeier, Plimmer and Franken2021), which consider employee voice as an antecedent, and the impact of this kind of leadership on organisational performance and development, while taking into account the issue related to the current cross-cultural contexts.

Moreover, the leadership dimension represents a buffer to move from the individual dimension of employee voice to the contribution of individuals to the overall organisational performance and strategy. Future research should focus on how the advances in employee voice literature can translate into actual organisational effectiveness improvements. Researchers might focus on organisational aspects to shed light on the impact of different HR practices on employee voice nowadays, considering multiple cultural backgrounds and knowledge that characterise workplaces. Moreover, since HR practices might present different levels of cultural specificity, research might adopt a comparative approach that considers this aspect and cultural differences across countries to ensure the structures and channels within organisational processes encourage individuals' voice behaviours (Kwon & Farndale, Reference Kwon and Farndale2020; Prouska, McKearney, Opute, Tungtakanpoung, & Brewster, Reference Prouska, McKearney, Opute, Tungtakanpoung and Brewster2022).

From the above considerations, Table 2 summarises the main topics that emerged from our results. We, then propose exploitative and explorative research avenues (Gervasi et al., Reference Gervasi, Faldetta, Pellegrini and Maley2022; Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Ciampi, Marzi and Orlando2020). More in detail, the former refers to avenues already studied but may still present interesting further development; the latter refers to those new avenues that need investigation or are now explored in a very initial stage. Based on these, we propose the consequent implications for future research.

Conclusion

The study of employee voice has been approached by multiple disciplines, which stemmed from various starting issues and theoretical premises converged in the three main management domains: IR, HRM and OB. Nevertheless, the fragmented literature in disciplines that hardly conversate with each other has hindered the needed cross-fertilisation necessary to advance our comprehension of voice phenomenon. By presenting a systematic literature review, rigorously supported by bibliometric analyses, that considered the multiple approaches and disciplines, this paper has identified three time periods of employee voice research, providing order about how the concept and its study have developed. Overall, this study's unique contribution to the theory of employee voice, which also is a methodological contribution in complementing previous literature reviews adopting both a systematic and a bibliometric approach, is sorting and ordering knowledge to pave future research avenues (Sandberg & Alvesson, Reference Sandberg and Alvesson2021).

Despite adopting a relatively innovative and rigorous bibliometric and systematic literature review approach, some limitations remain. In particular, one limitation may lie in focusing on a data set of articles published in journals ranked three and above in the 2021 Academic Journal Guide chartered by ABS, which may result in a lower representation in the data set of younger research streams. However, the dimension of the data set being considered allowed the identification of well-established themes. Moreover, to respond to the need for homogeneity of sources, our analysis has not considered books, conference proceedings or practice reports. Although our data set is still extensive, future studies could examine other further publications and scientific subjects to complement our results.

Similarly to previous bibliometric and systematic literature review studies (e.g., Sassetti et al., Reference Sassetti, Marzi, Cavaliere and Ciappei2018), one of the main limitations of this research lies in the trade-off between the need to provide a broader panoramic view of the field paying attention to the in-depth analysis of the content. Although this method offers a systematic way to structure literature reviews, it can't substitute for extensive reading and knowledge of the field. Research needs to consider bibliometric methods to integrate traditional reviews and a way to adopt, adapt and summarise findings in an overview that shows the relationship between articles and related topics. The objective of our study was to provide a science map of employee voice research through multiple bibliometric analyses. It is an abstraction derived from reality (Caputo et al., Reference Caputo, Pizzi, Pellegrini and Dabić2021). Science maps provide a starting point for analytical examination, but the interpretation strategy depends on the study focus and the authors' perspective (Zupic & Cater, Reference Zupic and Cater2015).

Conflict of interest

None.