INTRODUCTION

Education has long been considered a key aspect of economic and social development (Foster Reference Foster1967; Gyimah-Brempong Reference Gyimah-Brempong2011), and this is reflected in the annual budgetary allocations to education in countries across the globe (Al-Samarrai Reference Al-Samarrai2003; Frankema Reference Frankema2011). Particularly, in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), a minimal level of education is considered central to alleviating extreme poverty and combating diseases, as evident in African governments’ commitment to education as the principal instrument for modernisation (Foster Reference Foster1964). In view of this, successive governments in post-colonial Ghana have made conscious efforts to improve the quality of education in the country regardless of their ideological stands. For example, the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) government introduced in 1951 the Accelerated Development Plan (ADP), which abolished tuition fees, with the objective of achieving Universal Primary Education (UPE) for all Ghanaians within 15 years. A decade later, the CPP government introduced the 1961 Education Act, which made universal primary education compulsory in order to consolidate the ADP's gains (Francis Reference Francis2014; Aziabah Reference Aziabah2018). During the rule of the National Redemption Council (NRC), education reforms were introduced in 1974Footnote 1 to significantly change Ghana's education system. However, due to financial constraints, these reforms were only piloted in selected districts across Ghana (Quist Reference Quist1999; Kuyini Reference Kuyini2013). Upon taking office in 1981, the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) embarked on a nation-wide education reform aimed at revamping the deteriorated education system they had inherited. Similarly, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) government inaugurated a 20-member Presidential Committee, under the chairmanship of Professor Jophus Anamuah-Mensah, on 17 January 2002 to review Ghana's education system. This review led to the first major nationwide education reform under the Fourth Republic in 2007. Thus, Ghana has had two major education reforms (1987 and 2007) since independence in 1957. The study focuses on the 1987 reform for three reasons. First, it was the first major national education reform in post-independent Ghana that significantly transformed Ghana's education system (Quist Reference Quist1999; Osei-Mensah 2018 Int.). Second, several studies on the 1987 reform are descriptive and over rely on the ‘conditionality thesis’, which focuses on structural factors while neglecting ideational factors. Finally, unlike the 2007 reform which occurred under a democratic regime, the 1987 reform happened under military rule.

While several studies have been conducted to examine these reforms, most of these studies have either been descriptive in nature or relied on the ‘conditionality thesis’Footnote 2 to account for these reforms (Braimah et al. Reference Braimah, Mbowura and Seidu2014; Adu-Gyamfi et al. Reference Adu-Gyamfi, Donkoh and Addo2016). The conditionality thesis appeals to many scholars because many SSA countries underwent education reforms as part of the Structural Adjustment Policies (SAP) under the broader IMF and World Bank-led Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) agreement signed with many SSA governments in the mid-1980s (see Babalola et al. Reference Babalola, Lungwangwa and Adeyinka1999; Collier et al. Reference Collier, Guillaumont, Guillaumont and Gunning1997; Geo-JaJa & Mangum Reference Geo-JaJa and Mangum2003; Shah Reference Shah2013). We note that, in many of these studies, the concepts of conditionality and imposition have been used interchangeably. However, we contend in this study that ‘imposition’ is manifested through ‘conditionalities’. Thus, aid conditionalities become the mechanism through which exogenous actors (particularly the IMF and World Bank) undertake policy imposition in developing countries. Against this background and drawing on ideational literature and 30 semi-structured interviews with various education and policy actors, this study examines, in detail, the 1987 education reform in post-independence Ghana. Particularly, the study addresses the following questions: what were the factors that drove the 1987 reform? Did the 1987 reform lead to policy stability or change in Ghana's education system? Who were the key actors and what mechanisms did they employ to shape education reform? Focusing on the role of ideas and the related concepts of bricolage and translation, this study offers an alternative explanation for the adoption of the 1987 education reform in Ghana. While we recognise the influence of international organisations on that reform, we show that the main factors behind the reform are endogenous in nature. Thus, the reform was mainly as a result of both public outcry and the desire of the PNDC government to align the educational system to its political agenda. The quest for the 1987 reform was made easier when the IMF and World Bank made education reform a requirement under the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) it signed with the PNDC government in 1983. However, instead of imposing these conditionalities, we argue that the IMF and the World Bank engaged ideational mechanisms to influence the 1987 education reform process on ideational mechanisms (see Foli & Béland Reference Foli and Béland2014; Béland & Ridde Reference Béland and Ridde2016; Foli et al. Reference Foli, Béland and Fenwick2018; on ideational transnational influence see Orenstein Reference Orenstein2008; Haang'andu & Béland Reference Haang'andu, Béland and Schmitt2020). Consequently, the 1987 reform was the product of both exogenous and endogenous forces but the latter proved more influential, a claim at odds with the ‘conditionality thesis’, which focuses primarily on exogeneous forces. The ideational framework on bricolage and translation outlined in this paper to account for the impact of both endogenous and exogenous factors is applicable to multiple contexts beyond sub-Saharan Africa and the Global South and could be used to study change in education policy all over the world.

The paper begins with an outline of our ideational analytical framework on bricolage and translation in education policy reform. We then proceed to discuss the reasons why Ghana initiated the 1987 educational reform from the perspective of both policymakers (i.e. the interviewees) and official documents (1987 education report and the government's white paper). This is followed by an analysis of the key actors involved in the reform process and the ideational mechanisms these actors employed, namely bricolage and translation.

IDEAS, BRICOLAGE AND TRANSLATION

Much of the early public policy literature on policy stability and change tends to see change as following an evolutionary path resulting in incrementalism, which is characterised by the making of successive marginal changes to existing policy (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1959), and path dependency, where existing policies that take a particular course induce further movements along the same pattern (North Reference North1990; Pierson Reference Pierson2000). Thus, policies develop gridlocks, in the form of constituents, which makes transformative policy change very unlikely under most circumstances. In view of this, many scholars (e.g. Graham Reference Graham2013; Braimah et al. Reference Braimah, Mbowura and Seidu2014; Adu-Gyamfi et al. Reference Adu-Gyamfi, Donkoh and Addo2016) argue that the 1987 education reform in Ghana was incremental in nature and simply an extension of the 1974 reform. Where there has been the need to account for transformative change, in SSA and elsewhere around the world, the focus has been on exogenous forces (see Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Campbell Reference Campbell2004). However, there have been a number of works that highlight the possibility of path departing policy change stemming from endogenous factors rather than endogenous factors such as economic crises and international processes (Hall Reference Hall1993; Hacker Reference Hacker2004; Thelen Reference Thelen2004). This literature is relevant for the present paper because we need to explain why Ghana shifted from an education system fostering national identity and social solidarity in the 1950s and 1970s (see Foster Reference Foster1962) to a system based on economic imperatives in the late 1980s (Quist Reference Quist1999). An ideational framework is adopted to discuss the 1987 reforms in Ghana because ideas can both constrain and facilitate reforms while stressing the more general impact of endogenous factors that the literature on policy change has emphasised (Hacker Reference Hacker2004; Thelen Reference Thelen2004; Chakroun Reference Chakroun2010; Steiner-Khamsi Reference Steiner-Khamsi, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012; Takayama et al. Reference Takayama, Lewis, Gulson and Hursh2016). As such, the study employs Campbell's (Reference Campbell2004) concepts of bricolage and translation to explain how ideational mechanisms shaped the education policy process in Ghana (on these two concepts and how they can apply to sub-Saharan Africa see Haang'andu & Béland Reference Haang'andu, Béland and Schmitt2020).

The turn to ideas is appropriate for the analysis of education policy reform in Ghana in part because it recognises that both internal and external actors within the policy arena can influence the policy process autonomously from structural factors. Thus, ideational analysis enables us to elucidate the critical role of agency in education reforms, which is largely neglected by education researchers. Ideational approaches to politics tend to start from the assumption that policy actors face considerable uncertainty about the nature of their own interests or how to pursue them due to both cognitive limitations and incomplete information (on this issue see Blyth Reference Blyth2002). Therefore, the introduction of new ideas causes actors to reshape their policy preferences, making interests less stable than rational choice scholars might predict. Thus, norms and ideas partly constitute an actor's perceived interests and policy preferences, which are not simply a reflection of their structural position (Campbell Reference Campbell2004).

Thus, ideas affect policymaking rather than simply reflecting structural forces. They can serve as political weapons in the hands of concrete political actors who seek to shape public policy (Blyth Reference Blyth2002). This was the case with the 1987 reform, when the PNDC government sought to introduce populist and pro-poor ideas into the educational system running counter to some of the requirements of the IMF and the World Bank. The focus on actors is crucial here simply because ideational analysis stresses the agency of political and policy actors (Béland & Cox Reference Béland and Cox2011). Yet, while identifying key actors and the role they play in policymaking, Campbell (Reference Campbell2004) discusses two novel ideational mechanisms that allow us to trace concrete causal processes capable of shaping policy proposals and decisions: bricolage and translation.

First, according to Campbell (Reference Campbell2004), bricolage follows a logic of instrumentality by recombining already existing ideational and institutional elements to create something new. Thus, during the process of bricolage, policymakers attempt to re-use available materials in order to solve new problems (Baker & Nelson Reference Baker and Nelson2005; on bricolage see also Levi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1962 and Carstensen 2010). However, in education research, bricolage has been described either as basically a way to learn and solve problems by trying, testing and playing around or, to denote the use of multi-perspectival research methods (Kincheloe Reference Kincheloe, Hayes, Steinberg and Tobin2011; Phillimore et al. Reference Phillimore, Humphries, Klaas and Knecht2016). This study adopts Campbell's (Reference Campbell2004) definition of bricolage, which is consistent with Levi-Strauss's work because it brings to the fore the importance of agency and understanding local policy contexts in policymaking as espoused by education scholars such as Steiner-Khamsi (Reference Steiner-Khamsi, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012) and Tan & Chua (Reference Tan and Chua2015) in their discussions of education policy borrowing. Thus, bricolage enables policymakers to make significant policy changes to existing policies through endogenous processes that are ‘gradual, hermeneutic and discourse-intensive activity’ (Wilder & Howlett Reference Wilder and Howlett2014: 188). Bricolage is therefore a highly localised activity that can quickly respond to changing circumstances as resources at hand are combined to address new problems and opportunities. Yet, what differentiates Campbell's bricolage from policy borrowing is the unidirectional and coercive nature of policy borrowing, akin to that of the conditionality thesis. Simultaneously, bricolage ensures that policymakers look within their local environment to innovate or design solutions to address their local problems.

Second, translation is an ideational and institutional mechanism that combines endogenous and exogenous elements to bring about policy change in a particular jurisdiction by both adopting external ideas and adapting them to their new environment (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; on translation see also Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Bainton, Lendvai and Stubbs2015). Translation is very critical to policy studies because of globalisation, which has led to increased transnational movements of people, data and ideas. The outcome of such movements has been the influence of apparently shared policy agendas for various policy areas, including education. As Ozga et al. (Reference Ozga, Seddon, Steiner-Khamsi, Van Zanten, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012) rightly note, policy work is no longer operating within closed systems through bureaucratically organised, commanded and controlled processes. Rather, policy processes occur in complex systems involving borrowing and lending. The claim therefore is, behind the concept of translation, existing ideas and institutions provide repertoires that actors use to reframe and adjust policy innovations diffused from other jurisdiction so that they ‘fit in’ the adopting jurisdiction. The most important contribution of the concept of translation is that it shows how policy diffusion is not just about borrowing ideas from elsewhere but about adapting them to existing, endogenous ideational and institutional settings (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; see also Quist Reference Quist2003; Steiner-Khamsi Reference Steiner-Khamsi, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012). However, we must be aware of the fact that the translation of ideas does not occur always for rational reasons because the ideas borrowed are, in the words of Steiner-Khamsi (Reference Steiner-Khamsi, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012: 3), ‘proven to be good or – even worse – because they represent best practices’. There may be political and economic reasons that must be accounted for in the reform process. For example, the shift in the objective of Ghana's education during the 1987 reform was mainly due to the economic reasons advanced by the IMF and World Bank as they pushed for an Education for Knowledge Economy (EKE) globally.

We focus on these two mechanisms for our study because they point to the role of endogenous factors in policy change and, in the case of translation, the need to account for (exogenous) transnational diffusion and how it leads to jurisdiction-specific policy adaptation (Quist Reference Quist2003; Steiner-Khamsi Reference Steiner-Khamsi, Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow2012). Simultaneously, these two concepts address systematically the issue of both agency and transnational influence while stressing the role of ideas in a way that is far more explicit than most of the existing literature on endogenous yet transformative policy change (e.g. Hacker Reference Hacker2004; Thelen Reference Thelen2004; Streeck & Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). This is the case because bricolage and translation are inherently ideational concepts that stress the agency of the actors that draw on these two mechanisms to bring about policy change despite the threat of institutional inertia (Campbell Reference Campbell2004). Referred to as institutional entrepreneurs,Footnote 3 these actors ‘embrace, fabricate, manipulate and carry the different types of ideas’ (Campbell Reference Campbell2004: 101).

METHODS

This is a qualitative single case study that engages in thematic content analysis to identify patterns, themes, biases and meaning. The study draws on two types of data: interviews with policy actors and government documents. First, we conducted content analysis of key government documents under four key themes (i.e. objectives, financing, content and structure and duration) of the 1987 reform. The documents analysed included the 1951 ADPE, 1961 (Act 87), 1967 Kwapong Committee Report, 1974 Dzobo Committee Report, 1978 Republic of Ghana Constitutional Commission Proposal, 1987 Evans-Anfom Commission Report, and the 1979 and 1992 Constitutions of Ghana. Being mindful of the context within which these themes were being used in these documents, we further identified important themes such as ideas informing the reform processes, political influences, conditionalities, and key actors involved in the reform processes. In addition to the secondary data above, we also conducted 30 interviews with key policy personnel. To recruit interviewees, we developed selection criteria and an institutional map. Based on these two, respondents were recruited using stratified and purposive sampling techniques. We interviewed five officials of the Ministry of Education (MoE), Ghana Education Service (GES) and Non-Formal Education Division (NFED). These officers were the key personnel in charge of basic and secondary education reforms within their various agencies. We also interviewed two former Director-Generals of GES who were directly involved in the 1987 reform, and three key consultants of the MoE and GES who are education experts remotely involved with the 1987 reform and are currently assisting in the implementation of major policy decisions of the ruling NPP government. In addition, we conducted six interviews with members of the academia from the Universities of Ghana, Cape Coast and Winneba which included two former Vice-Chancellors who were knowledgeable about the 1987 reform. We also interviewed two traditional authorities (chiefs) knowledgeable in Ghana's education reforms. The remaining 11 interviews were conducted with International Governmental Organisations (4) including the World Bank, UNICEF and UNESCO; International NGOs (three) including World Education; and local NGOs (5) including the Ghana National Education Campaign Coalition (GNECC) and the Ghana National Association of Teachers (GNAT). These 11 interviewees were mostly circumstantial respondents but with great depth of knowledge of education reforms in Ghana due to the nature of their work. The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide with the aim of co-creating knowledge with the respondents. The qualitative software NVIVO v12 was then used to undertake a thematic analysis of the interview data. Finally, we wove together the findings from the interview data and document review to develop a coherent argument in examining the 1987 reform.

THE MAKING OF THE 1987 EDUCATION REFORM

Focusing on exogenous and structural forces, many scholars (e.g. Akyeampong Reference Akyeampong2010; Braimah et al. Reference Braimah, Mbowura and Seidu2014; Nudzor Reference Nudzor2017) have attributed the 1987 reform in Ghana to the numerous aid conditionalities imposed by the IMF and the World Bank in the 1983 ERPFootnote 4 agreement. For example, Braimah et al. (Reference Braimah, Mbowura and Seidu2014: 147–8) argue that:

The 1987 education reform was a political as well as an economic imposition by the IMF/World Bank in an attempt to salvage the economic downturn of the Ghanaian economy. This external imposition to reform the school system was presented superficially, as a home-grown educational policy by the military government – the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) headed by Jerry John Rawlings.

Yet, interview data collected for this research project point to a different, more important side of the story. The data suggest that, since independence in 1957, the quest for educational reforms in Ghana has been embedded in the idea held by successive governments that the country's public education system ought to foster national unity and promote economic and social development (Foster Reference Foster1962; Quist Reference Quist1999, Reference Quist2003). In an interview with Anarfi (2018 Int.), he noted: ‘Every substantive government from Nkrumah's time up to date wants to change the style of education to suit the modern condition or the present-day conditions.’ Likewise, Acquaye (2018 Int.) also noted: ‘Society is dynamic, and the technology is advancing and if you want to remain in the global economy, you need to change your curriculum and change your educational system.’ As Quist (Reference Quist2003: 14) succinctly puts it:

This model [the introduction of the JSS and SSS concepts during 1974 and later 1987 reforms] was introduced voluntarily by an independent nation-state that had over the years reflected on the efficiency and effectiveness of its educational system, particularly the secondary level, in addressing national needs, responding to national demands and calls for its reform that would promote and accelerate national development.

In view of this, and without being solely compelled to do so by exogenous forces, the PNDC government established an Education Commission (EC) chaired by Dr Emmanuel Evans-Anfom in 1984 to review and report on basic, teacher, technical/vocational and agricultural education in Ghana in line with PNDC's anti-elitist, pro-poor, pro-rural social policies (Education Commission 1986).

Justifying the ‘need to reform’ (Cox Reference Cox2001), Flt. Lt. Rawlings described the existing education system as one that was oppressive and stultified the Ghanaian child (Fobi et al. Reference Fobi, Koomson and Godwyll1995). Rawlings identified three key forms of oppression rooted in the existing education system: the denial of equal opportunity; the overemphasis on conformity at the expense of creativity; and the strong focus on self-interest rather than on social solidarity. Thus, Rawlings envisaged an ‘education system which was non-oppressive but transformative and values creativity as well as promotes social justice’ (Fobi et al. Reference Fobi, Koomson and Godwyll1995: 66). Many Ghanaians and scholars also decried the deprived and not fit for purpose nature of Ghana's education system in the early 1980s, when the PNDC took power. These views were summed up in the National Education Forum (NEF) report in 1999 as follows: ‘by 1983, Ghana's educational system, which until the mid-1970s was known to be one of the most highly developed and effective in West Africa, had deteriorated in quality. Enrolment rates, once among the highest in the sub-Saharan region, stagnated and fell’ (National Education Forum 1999: 9).

Thus, the 1987 reform cannot be attributed only to aid conditionalities from the IMF and the World Bank as suggested by some scholars. In an interview conducted as part of this project, Apanbil (2018 Int.) indicated that: ‘Our [Ghana's] basic education system before Rawlings took over had virtually collapsed … it was not functioning properly … We therefore had to reform the [educational] system to make it relevant to our environment. The IMF can't tell us what to do.’ Similarly, Anamuah-Mensah (2018 Int.) also indicated that the various reforms came about due to the: ‘General recognition by large majority of the population that education system requires a face lift … people during the period were complaining about their kids completing school and not doing anything.’ Again, in another interview, Dadzie (2018 Int.) noted: ‘It [the 1987 reform] was made by the society [people] itself. A lot of complaints about the need to change the [existing] system, the need to produce the skills we need as a country.’ Thus, it is clear from our interview data that the introduction of the 1987 education reform was not primarily the product of an exogenous, structural imposition from the Bretton Woods Institutions, but rather the result of an apparent need recognised by domestic actors to make education more relevant to Ghana's socio-economic development.

More specifically, the decision to embark on the 1987 educational reform stemmed from two main reasons. First, there was public outcry about the quality of the existing education system because the policy recommendations under the 1974Footnote 5 education reform had not been fully implemented. Accordingly, the general public saw the need for an education reform as a national emergency. Second, the PNDC government saw the existing education system as inadequate for its transformative developmental agenda (Fobi et al. Reference Fobi, Koomson and Godwyll1995). These two primary reasons behind the impetus for reform were then augmented by the demands from the IMF and World Bank for the government to cut down social expenditure under the ERP agreement in 1983, as shown in Table I. While the IMF and World Bank demanded cuts in social expenditure, which included education spending, the nature and form of the cut was primarily the preserve of the PNDC government. Regarding education, the IMF and World Bank recognised that education was a political demand; hence, imposing conditionality was not feasible. As Ackwerh (2018 Int.) indicated:

there was no hand in it [1987 education reform] … And actually, what the Bank [World Bank] does is actually funding their strategy … So, it's they [government] who decide what they want to do. They can come to the Bank … we don't force them to do anything … They decide that we want to do this and we provide our ideas and views but the decision lies with the government.

These Bretton Woods Institutions, therefore, adopted ideational mechanisms through negotiations, ministerial meetings, workshops and global conferences to push through its education reform ideas (i.e. Education for Knowledge Economy) in Ghana and the Global South. This remark suggests that, while endogenous ideational and political factors were the main factors behind the 1987 reform, yet exogenous forces did play a significant role in the education reform process except not through a form of an ‘imposition’ or ‘conditionality’ but rather through ideational processes, something we explore in greater detail in the next section.

Table I Summary of factors responsible for the 1987 education reform.

KEY ACTORS AND THEIR INFLUENCE

The PNDC government set up an Education Commission under the chairmanship of Dr Emmanuel Evans-Anfom in 1984 to review and make appropriate recommendations for the reform of the existing education system. The Commission was made up of 14 local members and six international consultants including two well-known authors (Ngugi wa Thiong'o from Kenya and Chinua Achebe from Nigeria) and a distinguished Brazilian education expert Paulo Freire. However, the six international consultants did not participate in the work of the Commission (EC 1986). Thus, only the 14 local members made up of Ministry of Education (8), West Africa Examination Council (1), National Union of Ghana Students (1), Ghana National Association of Teachers (1), Education Unit of Missions (2) and Trade Union Congress (1) served on the Commission.

The commissioners used several means available to them to acquire the needed data for their report. They reviewed past reforms, particularly the 1974 reform, and the available educational literature in general. They also requested for the submission of memoranda from the public. Unfortunately, not many memoranda were submitted due to the political atmosphere at the time. The activities of the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDRs) established in 1984 created an atmosphere of fear, panic and general mistrust (Agyeman-Duah Reference Agyeman-Duah1987; Hutchful Reference Hutchful1997). The outcome was a ‘culture of silence’ with a non-existent civil society (Ankomah Reference Ankomah1987). To overcome this challenge, the Commission visited several basic and senior secondary schools; vocational and technical institutes, and tertiary level institutions to interact with students, teachers and administrators. Due to inadequate financial support, these visits were limited to the Accra-Tema metropolis (Aheto-Tsegah 2018 Int.; Apanbil 2018 Int.). Thus, the views of those in the rural areas were not captured by the Commission. The Commission also interviewed representatives of some selected institutions that were seen to be stakeholders. These included government agencies that were education-related such as Ghana Education Service (GES) and the Examination Council; Trade and Teacher Unions; National Union of Ghanaian Students (NUGS) and the Education Units of the various missions in Ghana (EC 1986).

In addition to the above, the work of the EC was also informed by global developments in education. Ghana is a signatory to several international declarations and conventions on education. These include the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and cultural Rights. These conventions affirmed the right of individuals to an education system that respects their personality, talents, abilities and cultural heritage. In particular, the global push for Education for Knowledge Economy (EKE) by the World Bank and IMF impacted greatly on educational reforms in SSA countries that undertook structural adjustment programmes funded by these two institutions (Kadingdi Reference Kadingdi2004; Kuyini Reference Kuyini2013; Nudzor Reference Nudzor2017). The EKE was in line with the neo-liberal, modernist and market-driven policy orientation of the World Bank and IMF. Consequently, the World Bank and IMF pushed for education systems that fostered privatisation, cost recovery and the rhetoric of EKE in Ghana during the implementation of the ERP. It is instructive to note that the IMF and the World Bank recognised that imposing a neo-liberal and market-driven education reform was incompatible with the core ideals of the socialist-oriented PNDC military government. As such, any form of a neo-liberal policy imposition on education reform on a populist and socialist-oriented government such as the PNDC would have been met with stiff opposition. Thus, these international organisations employed ideational tactics such as organising ministerial meetings, workshops and global conferences to drive home the need for countries in the Global South such as Ghana to adopt the EKE paradigm. Promising financial assistance for education reforms based on the EKE, many countries, including Ghana, adopted the EKE principles in re-aligning the objective of their education system. While it is impossible to talk about exogenous imposition, the 1987 reform reflected this market-oriented thinking pushed by the World Bank and the IMF.

First, the objective of Ghana's education shifted from the ideals of national integration, nation-building and disabusing the minds of citizens of colonial history, experiences and vestiges in 1957 to emphasis on the creation of a highly skilled, flexible human capital needed to compete in a global market. Thus, the 1987 reform aimed at creating an individual who was enterprising and a competitive entrepreneur who possessed transferable core skills to become a compliant pro-capitalist worker (King Reference King2004; Nudzor Reference Nudzor2017).

Second, as noted already, the IMF and World Bank pushed for cuts in public education spending and proposed that Ghanaians self-finance their education. The demand for self-financing of education was, however, partly rejected by the populist and socialist-oriented PNDC government during the 1987 reform. Accordingly, cost-recovery measures in what became known as ‘cost-sharing’ were introduced under the 1987 reform. However, for fear of political backlash stemming from the contrast between this neoliberal approach and the party's populist and pro-poor stands, the PNDC government could not introduce cost-sharing at the basic level of education. Thus, cost-sharing was limited to secondary and tertiary levels of education under the 1987 reform. The outcome was the reduction in secondary education from four to three years, the introduction of school fees and academic facility user fees (AFUF),Footnote 6 and increased privatisation of education services. These measures began the alignment of Ghana's educational policies towards the demands and trends of international and pro-capitalist institutions (Kuyini Reference Kuyini2013; Nudzor Reference Nudzor2017).

THE 1987 EDUCATION REFORM: STABILITY AND CHANGE

In addressing the issue of stability and change, Campbell (Reference Campbell2004) argues that when the different dimensions of a policy are analysed, we may ascertain the direction of change of these dimensions. We therefore analyse the 1987 education reform under the four major dimensions identified earlier. Analysing the 1987 reform within this framework reveals interesting findings.

The first dimension of the reform dealt with the objective of education. As discussed earlier, the global push for EKE by the IMF and World Bank led to a shift from the identity-creating education system established in 1957 to an economic-value focused education system. Thus, education was to make Ghanaians competitive in the global market. Hence, the objective of the 1987 education reform was path departing and not path dependent. This path departing change was due to two reasons. First was the economic crisis Ghana experienced in the wake of global oil hikes, a drop in world cocoa prices and the deportation of several thousands of Ghanaians from neighbouring Nigeria (Ninsin Reference Ninsin1996; Tsikata Reference Tsikata1999). This forced the PNDC government to turn to the Bretton Woods Institutions for financial bail-out. The bail-out did come, but with some conditionalities, which included the reduction in public education spending. However, reducing public education spending was at variance with the ideals of the populist and socialist-oriented PNDC government. To navigate this challenge, the IMF and the World Bank employed ideational tools such as meetings, conferences, country annual reports and workshops to begin a global push for neo-liberal education systems that sought to dislodge the post-independence nationalist and socialist education systems put in place by nationalist leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania (Trowler Reference Trowler1998; Nudzor Reference Nudzor2017). The push for a global paradigm shift in education and the financial resources of IMF and World Bank enabled them to influence education systems across SSA through workshops, publication of country annual reports and global conferences on education.

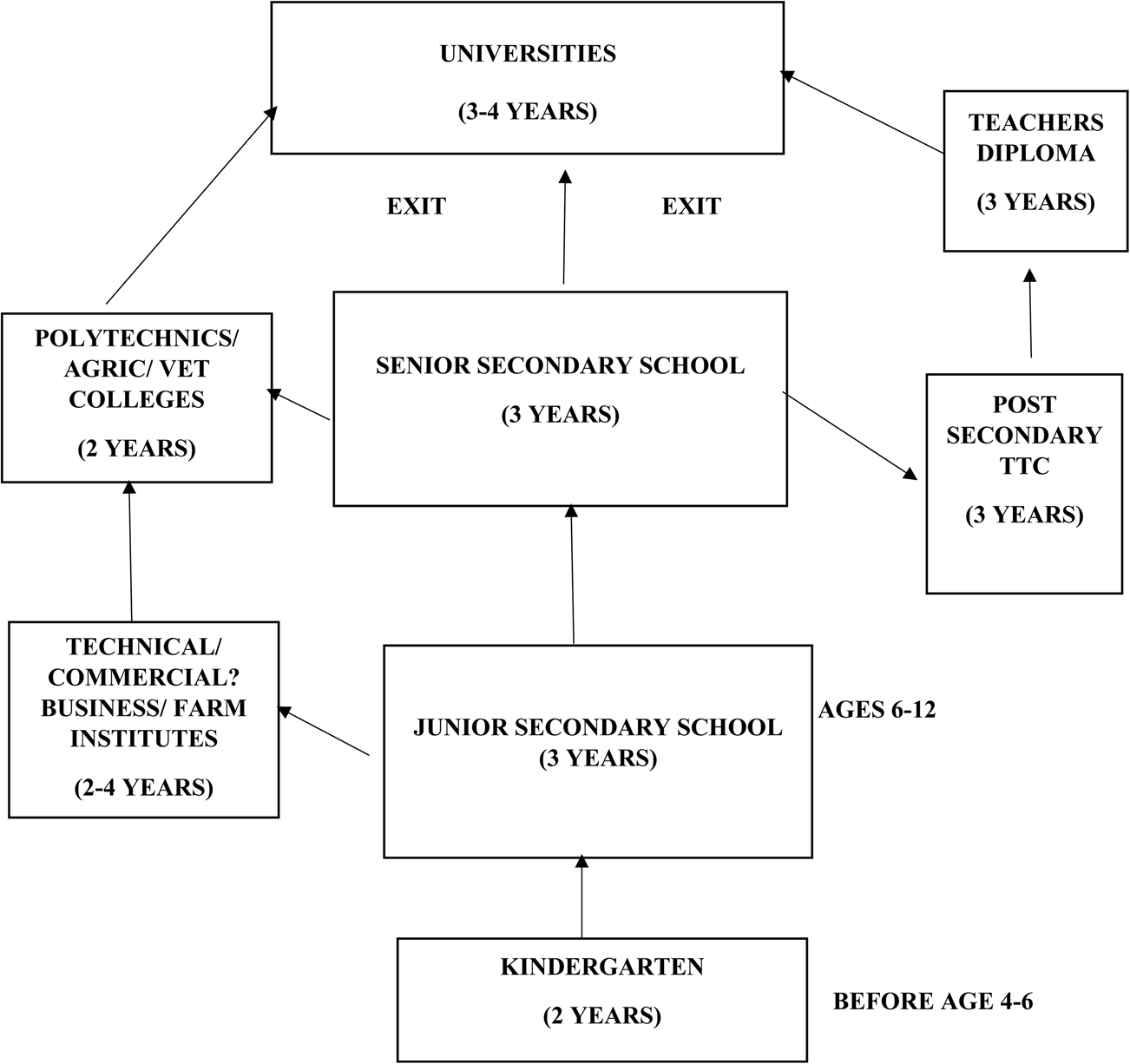

The second dimension of the 1987 reform was the structure of the education system and the duration of pre-tertiary education. Again, as noted already, the government was required to reduce public spending in education under the ERP agreement. As such, pre-tertiary education had to be restructured by the 1987 reform. The middle school and sixth form systems were abolished. A 3-year Junior Secondary (JSS) education was introduced to replace the abolished middle school. Secondary education (SSS) was also reduced from 5 years to 3 years. This considerably reduced pre-tertiary education by 5 years (i.e. from 17 years to 12 years). Even though this reduction had begun under the 1974 reform (i.e. from 17 years to 13 years), it was never fully implemented. The 1987 reform embarked upon a nationwide restructuring and reduction in the number of years as opposed to the pilot implementation under the 1974 reform.

The third dimension was the financing of basic education. Even though the IMF and World Bank required the PNDC government to reduce public spending on education, it was politically suicidal for the PNDC to introduce any form of cost-sharing or fees at the basic level due to its populist and pro-poor stands. In an interview with Osei-Mensah (2018 Int.), he said: ‘Quantum [education spending] may be dropping in terms of percentage of it to our budget in financing, but then clearly you can see that every government puts in a lot of money to basic, so there's kind of consistency when it comes to financing basic education.’ Consequently, the government continued with the free universal basic education, but introduced cost-sharing measures at the secondary and tertiary levels of education. Yet, to reduce education spending at the basic level, the government reduced the duration of basic education from 10 years to 9 years (i.e. 6 years of primary education and 3 years JSS).

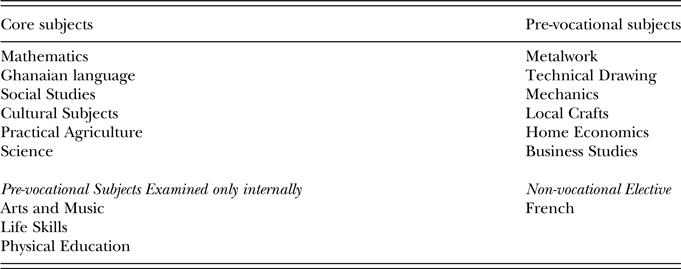

The last dimension of the 1987 reform dealt with the content of the education system. While the subjects for primary education under the 1974 reform were maintained, there were minor changes in the JSS curriculum to emphasise pre-vocational education. This was to enable students to develop not only their cognitive skills, but also their manual skills. In all, students were required to take 13 subjects comprising 12 core subjects and 1 non-vocational elective in JSS, as shown in Table II. Under the 1974 reform, students were required to do 12 core subjects. In addition, they were required to self-select 2 pre-vocational and technical subjects from a list of 13 subjects. This meant that 14 subjects were learned at JSS level. However, the 1987 reform reduced this number to 13 and specified the pre-vocational subjects that students were required to take.

From the above discussions, both path departing and path dependent changes occurred when the dimensions of the 1987 reform are specified as above. The objective and the structure and duration of Ghana's education system under the 1987 reform witnessed path departing changes as discussed earlier. These changes were partly due to the economic crisis that necessitated the ERP agreement in 1983 and the push for a global paradigm shift by the IMF and World Bank. Again, the change was also due to the limited number of veto playersFootnote 7 at the time. As Tsebelis (Reference Tsebelis1995) argues, there is a reduced probability of enacting a policy change when there is an increase in the number of veto players in the policy space. The military government at the time had gradually introduced a culture of silence (Agyeman-Duah Reference Agyeman-Duah1987; Gyimah-Boadi Reference Gyimah-Boadi1990), which resulted in a non-existent civil society. Thus, the policy space was the reserve of the military regime and its associates. This made it easy for the government to undertake the shift in the objective of education as the government did not entertain dissenting and opposing views, hence there were no genuine ‘veto players’ capable of shaping outcomes except the IMF and World Bank who had the financial resources to back their policy recommendations.

On the other hand, there was policy stability in the financing of basic education. This was due to the increased cohesion of the members of the PNDC government and its associates to oppose any attempt by the IMF and World Bank to introduce fees and cost-sharing at the basic level. A cost-sharing policy at the basic level was seen by the PNDC government as inconsistent with its ideological claims of being a government of the poor and vulnerable in society. As discussed earlier, when there is an increase in the cohesion of a given veto player's constituent group, policy change may be difficult to achieve (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995; Trebilcock Reference Trebilcock2014). This was the case with financing basic education.

With respect to the content of the education system, the 1987 reform was largely path dependent with some incremental changes at the JSS level. One would have expected that once the objective of education had changed, the content would have also received considerable revision. However, this was not the case for one simple reason: the government was constrained with regard to the availability and capacity of existing teachers to deliver any dramatic content changes. Again, any dramatic change to the curriculum would have been met with strike actions from the GNAT (Apanbil 2018 Int.). This institutional constraint forced the government to introduce minor changes to the existing curriculum.

BRICOLAGE

The Evans-Anfom Education Commission ostensibly recombined existing educational principles and practices outlined in previous educational reforms (particularly the 1974 reform) to innovate and craft solutions to address the identified problems in Ghana's education system in a process Campbell (Reference Campbell2004) referred to as bricolage. To begin with, the government instituted a 20-member EC to reform the education system. However, six of the members who were all international experts failed to participate in the work of the Commission. While the reason for their failure to participate remains unclear, many believe it was due to the culture of silence that had permeated Ghanaian society at the time (Osei-Mensah 2018 Int.). As a result, only 14 members, who were all Ghanaians, participated in the reform process. Even though the Commission reviewed international scholarly works on education reforms, they did not directly benefit from the international perspectives of the six foreign experts. Again, due to the economic challenges at the time, the government did not provide adequate funds for the Commission to embark on international travels to learn best practices from other countries. In addition, due to the unavailability of funds and the military regime in place, the Commission limited its public engagement to a few selected individuals and institutions in Accra and Tema, depriving other segments of the society the opportunity to participate in the reform process. Confronted with these challenges, the Commission had to rely on existing educational principles and practices to innovate and address the perceived challenges within the existing education system.

In line with this, the Evans-Anfom Commission reviewed existing policies to guide them in their recommendations. Particularly, the work of the Commission was influenced by the education reports issued by the Konuah and Dzobo Education Committees in 1971 and 1974, respectively. For example, the recommendations of the Dzobo Committee in 1974 had already led to a significant reduction in the number of years of pre-tertiary education from 17 years (6:4:5:2)Footnote 8 to 13 years (6:3:4Footnote 9). In addition, the 1974 reform introduced and piloted the JSS/SSS concepts to replace the middle school and ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels. The Evans-Anfom Commission maintained this structure but recommended a nationwide roll-out of the JSS/SSS concept in 1987. Again, they maintained the 9-year basic education and only reduced secondary education by a 1 year. This reduced pre-tertiary education from 13 years (6:3:4) to 12 years (6:3:3).

Thus, the EC and the actors involved in the 1987 reform basically tapped into their existing repertoire of policies and practices to innovate through bricolage. The outcome of the 1987 reform was therefore a new education system that resembled the previous education system introduced in 1974. As noted by Campbell (Reference Campbell2004), bricolage could either be substantive or symbolic. Substantive bricolage follows the rational-choice logic of instrumentality where actors are guided by their self-interest and goals. Symbolic bricolage, on the other hand, follows the cultural logic of appropriateness where individuals seek to act appropriately vis-à-vis their cultural environments (Campbell Reference Campbell2004; Parsons Reference Parsons2007). The 1987 education reform was a combination of these two types of bricolage. Substantively, the reform was to aid the PNDC government in its transformational agenda by producing the needed labour force for the state (Osei Reference Osei2004; Osei-Mensah 2018 Int.). In an interview with Dzeagu (2018 Int.), she said: ‘the 1987 reform was expected to equip students with the skills to enable them to transition into the world of work after junior high [school] and be able to function adequately’. However, the decision to maintain and continue financing basic education in spite of the harsh economic conditions at the time was purely symbolic as the government attempted to stick to its socialist leanings. The symbolic bricolage was for two reasons. First, it was an attempt by the PNDC government to generate public acceptance and legitimacy for the 1987 reform within the broad social environment. Second and most importantly, it was a means of assuring Ghanaians that regardless of the ERP agreement signed with the IMF and World Bank in 1983, the PNDC government would continue to introduce and implement pro-poor and pro-rural policies.

TRANSLATION

As suggested above, translation involves the ‘combination of externally given elements [ideas] received through diffusion and domestically given ones inherited from the past’ (Campbell Reference Campbell2004: 80). Although the 1987 reform did not see very much of translation due to the military nature of the government, limited translation efforts from the IMF and World Bank were significant enough to change the objective of Ghana's education. Typical of military regimes, the policy space was limited to government and quasi-government agencies with virtually no room for both internal and external non-state actors. Again, the six international consultants who were invited to be part of the 20-member Evans-Anfom Education Commission did not honour the invitation. As a result, the Commission was made up of the remaining 14 local members selected from the government and its allied agencies.

However, the dire economic situation of the Ghanaian state in the early 1980s forced the PNDC military government to turn to the IMF and the World Bank for a financial bail-out. The outcome was the signing of an economic agreement (i.e. the ERP) in 1983 that effectively required the government to roll back its welfare programmes and rethink the role of the state in providing education and other social spending. This led to some limited translation of ideas during the 1987 education reform as the ERP agreement provided an avenue for the IMF and World Bank to articulate the EKE policy. The World Bank and IMF articulated these ideas through ministerial meetings, workshops and global conferences. Thus, even though the processes leading to the 1987 education reform were mainly about bricolage, there was an element of translation due to the work of the IMF and World Bank in SSA. As indicated earlier, the IMF and World Bank were not directly involved in the 1987 education reform. However, their push for a paradigm shift from the nationalistic and identity-creating objectives of education to the EKE in the Global South during the ERP negotiations in 1980s influenced Ghana's 1987 education reform. In addition, the work of the Evans-Anfom Commission was influenced by the annual reports issued by these Bretton Woods Institutions highlighting the need for Ghana to align its education objectives to that of the EKE paradigm. These annual reports were reviewed by the Commission and ultimately led to the objective of Ghana's education system changing to EKE, as discussed earlier. These agencies continued to influence education reforms through their participation in government forums such as the Structural Adjustment Participatory Review Initiative (SAPRI) and the Citizens Assessment of Structural Adjustment (CASA) (Structural Adjustment Participatory Review International Network 2002). Despite the limited translation, it is important to note that it deals with the mix of exogenous and endogenous factors to inform the 1987 education reform, which is a key aspect of our paper. However, in the end, we discovered that endogenous factors associated with bricolage proved the most influential. Thus, we can say the fact there was less translation and more bricolage does back our claim about the greater influence of endogenous factors over exogenous factors.

CONCLUSION

This paper examines the 1987 education reform and challenges the assertion that reforms in Ghana and other SSA countries are mainly an imposition from exogenous forces, particularly the IMF and World Bank. Using an ideational framework, the paper has demonstrated how the Education Commission of 1984 employed the ideational mechanisms of bricolage and translation to innovate and bring about the 1987 reform. This contrasts with the conditionality thesis, where policymaking in developing countries such as Ghana is seen to be externally induced. As argued, the 1987 education reform was not an imposition from the IMF and World Bank due to the ERP signed between them and the PNDC government in 1983. However, endogenous (domestic) factors including the demand from the Ghanaian people for education reform and the desire of the PNDC government to introduce education reform in line with its pro-poor and populist policies occasioned the 1987 education reform. These endogenous factors coincided with the demands by the IMF and World Bank for the PNDC government to reduce its social expenditure including education spending as a condition for assessing loans under the ERP agreement. While meeting such a demand was inconsistent with the objectives of a pro-poor and socialist-oriented PNDC government, as discussed earlier, the IMF and the World Bank employed ideational tools in the form of meetings, workshops and conferences to influence the 1987 education reform in Ghana.

The discussion above also shows that due to the military rule at the time, the policy space was closed to non-state actors except the teacher unions and mission schools which provided critical services within the education system. Nevertheless, due to the culture of silence at the time, these non-state actors could not influence the reform process very much as the government did not kowtow to divergent and dissenting views. However, the IMF and World Bank were able to influence the reform process through ideational mechanisms, and not imposition, hence the adoption of the EKE. This was done through the issuing of country annual reports, ministerial meetings, workshops and conferences that highlighted the essence of the EKE and the financial assistance they provided countries that opted for the EKE. Here, while we reject the imposition thesis, we recognise that, although endogenous factors shaped the reform, exogenous forces also contributed to shape it through ideational instruments.

Again, the reform was characterised by both path departing and path dependent change as shown in Table III. The objective of Ghana's education system witnessed a path departing change, while the content, structure and duration of the education system saw path dependent changes. These changes were however begun in 1974 when the NRC military government established the Dzobo Education Committee to reform the education system in place. Regardless of the IMF and World Bank's conditionality of reducing government's social expenditure, the 1987 education reform maintained the free basic education that was introduced under the 1951 Accelerated Development Plan for Education (ADPE). Yet, the IMF and World Bank's global push for the EKE through ideational instruments led to path departing changes in the objective of Ghana's education system. Thus, the work of the Evans-Anfom Commission was influenced by both bricolage and translation processes.

Table III. Summary of the 1987 Education Reform.

Appendix. Structure of Formal Education in 1987.