No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 March 2011

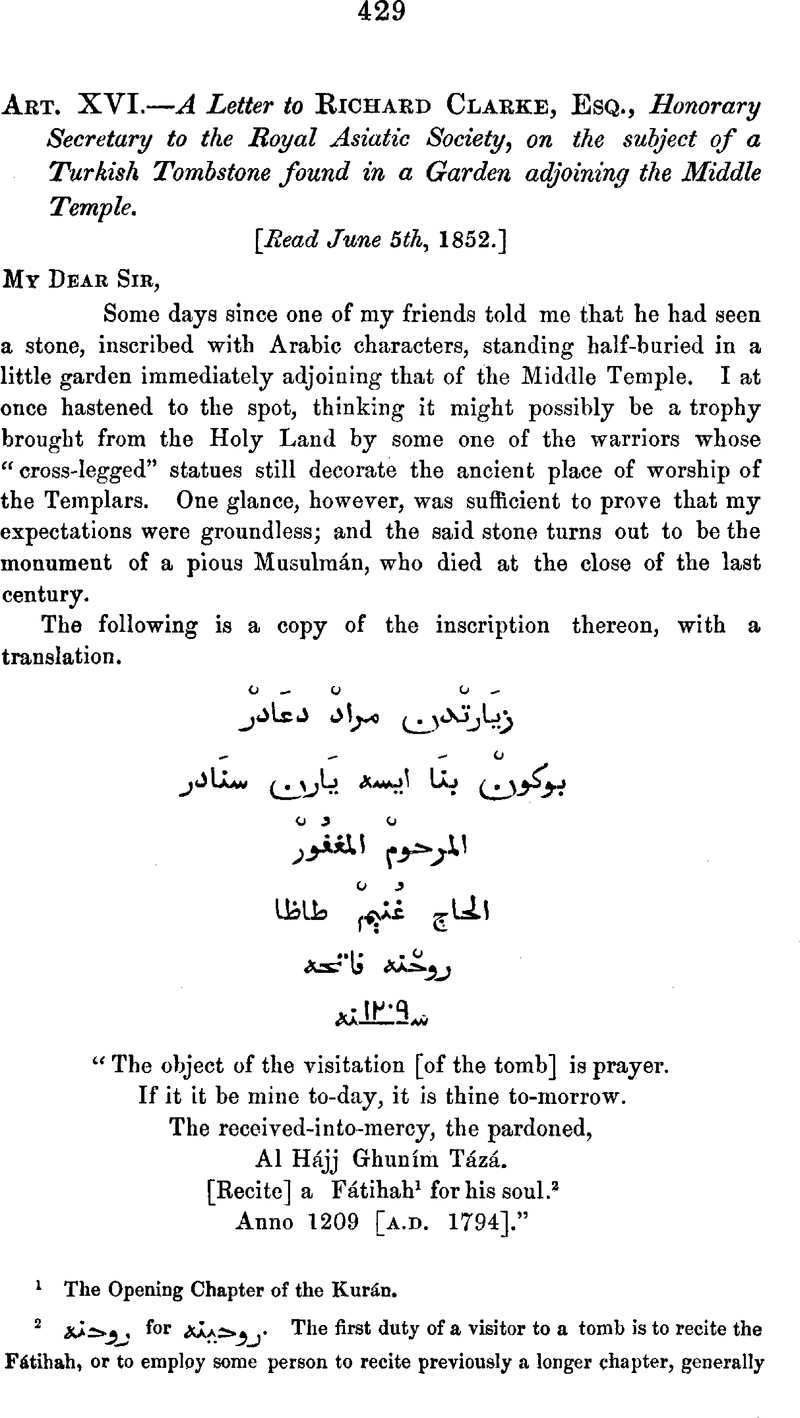

page 429 note 1 The Opening Chapter of the Kurán.

page 429 note 2 ![]() for

for ![]() The first duty of a visitor to a tomb is to recite the Fátihah, or to employ some person to recite previously a longer chapter, generally the thirty-sixth, or even the whole Kurán; or sometimes the visitor recites the Fátihah, and, after hiring a person to perform a longer recitation, goes away before he commences. —See Lane's Arabian Nights, vol. 1. p. 71.Google Scholar These prayers for the departed are believed to increase his happiness in futurity or to diminish his misery.—Ib p. 249, and see Lane's Modern Egyptians, vol. ii. p. 240.Google Scholar In describing the visitation of the tombs of saints, Mr. Lane, in another place, observes that these acts of devotion are generally performed for the sake of the saint; though merit is likewise believed to reflect upon the visitor who makes a recitation. The latter, at the close of the ceremony, adds, “O God, I have transferred the merit of what I have recited from the excellent Kurán to the person to whom this place is dedicated,” or “to the soul of this Walí.” Without such a declaration, or intention to the same effect, the merit of the recital belongs solely to the person who performs it.—Modern Egyptians, vol. i. pp. 304–5.Google Scholar

The first duty of a visitor to a tomb is to recite the Fátihah, or to employ some person to recite previously a longer chapter, generally the thirty-sixth, or even the whole Kurán; or sometimes the visitor recites the Fátihah, and, after hiring a person to perform a longer recitation, goes away before he commences. —See Lane's Arabian Nights, vol. 1. p. 71.Google Scholar These prayers for the departed are believed to increase his happiness in futurity or to diminish his misery.—Ib p. 249, and see Lane's Modern Egyptians, vol. ii. p. 240.Google Scholar In describing the visitation of the tombs of saints, Mr. Lane, in another place, observes that these acts of devotion are generally performed for the sake of the saint; though merit is likewise believed to reflect upon the visitor who makes a recitation. The latter, at the close of the ceremony, adds, “O God, I have transferred the merit of what I have recited from the excellent Kurán to the person to whom this place is dedicated,” or “to the soul of this Walí.” Without such a declaration, or intention to the same effect, the merit of the recital belongs solely to the person who performs it.—Modern Egyptians, vol. i. pp. 304–5.Google Scholar