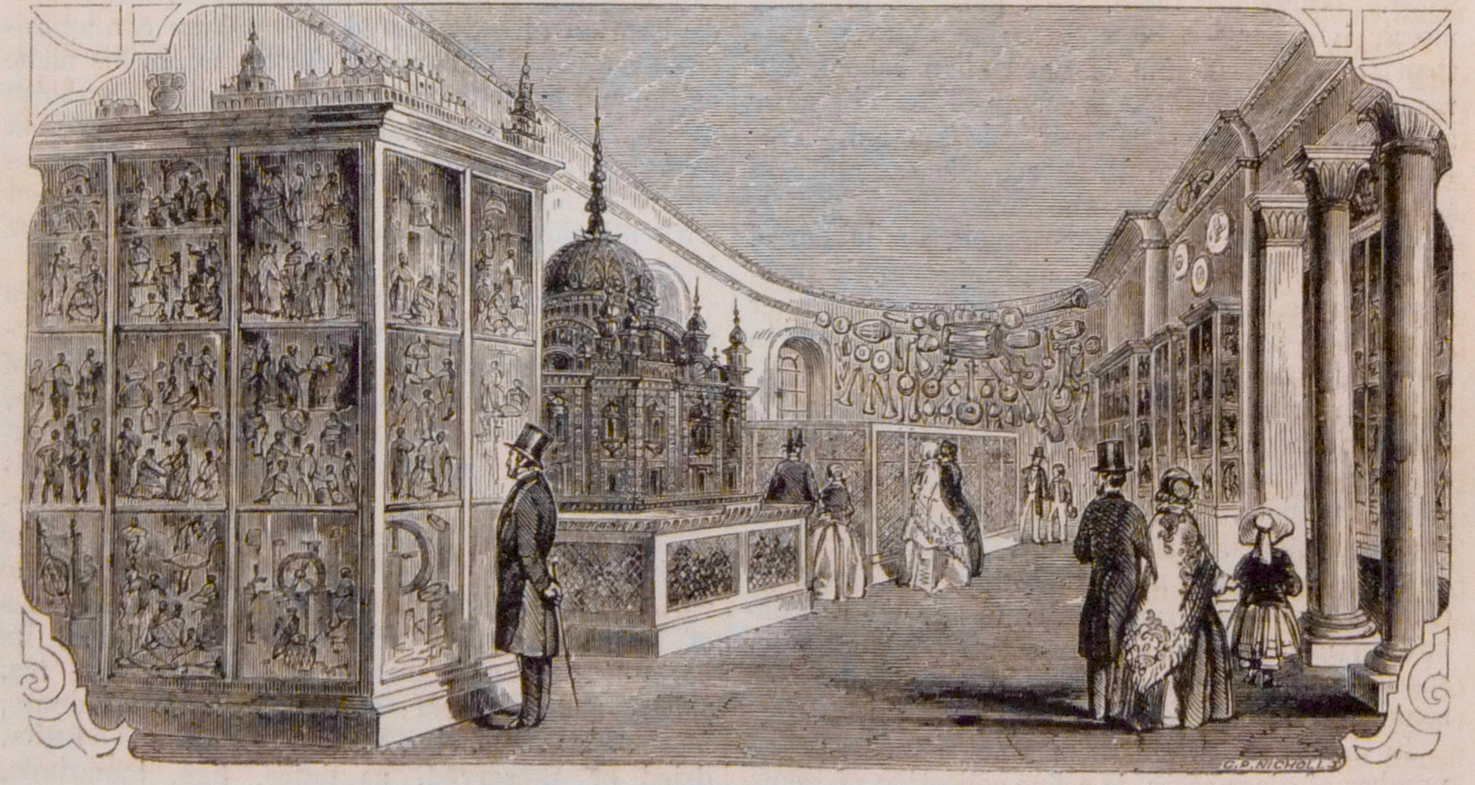

Conceived initially to perform a transient role in sacred ritual, figurines moulded in unfired clay defied their evanescent nature to achieve popularity in a wider secular context in India. Later they were further adopted for a representational role in Western museum displays and exhibitions. Although modest in scale and in their raw materials, in the case of the museum of the East India Company (EIC)—where the present investigation has its origins—the models of human and other figures discussed here became so numerous as to form one of the defining features of the display, although their role in this respect has long been forgotten. The value of these figures to curators and their appeal to the public lay in their ability to summon up a range of aspects of everyday life on the sub-continent in a direct and vivid way. As observed by a visitor to the museum (Figure 1) at the Company's headquartersFootnote 1 in 1858—that is to say, on the very eve of its winding-up:

The models of figures may be numbered by the thousand. Perhaps the most useful and interesting are those which represent the workers at their several crafts and occupations … we see them at work, weaving, digging, carrying water, tilling the soil, grinding the corn, cooking their food, or juggling, conjuring, snake-charming, and exercising themselves in feats of agility or muscular exploits—at all their occupations, in short, as they would be found actually engaged on their native soil.Footnote 2

It was as if the models had been custom-made with this display function in mind—and indeed by the time of the museum's dispersal just over 20 years later, some were undoubtedly being commissioned specifically for that purpose, but their earlier history lies elsewhere.

Figure 1. A visitor to the India Museum admires a display of model figures (left). Source: From The Leisure Hour 7 (1858).

Production of the figures: context, chronology, and distribution

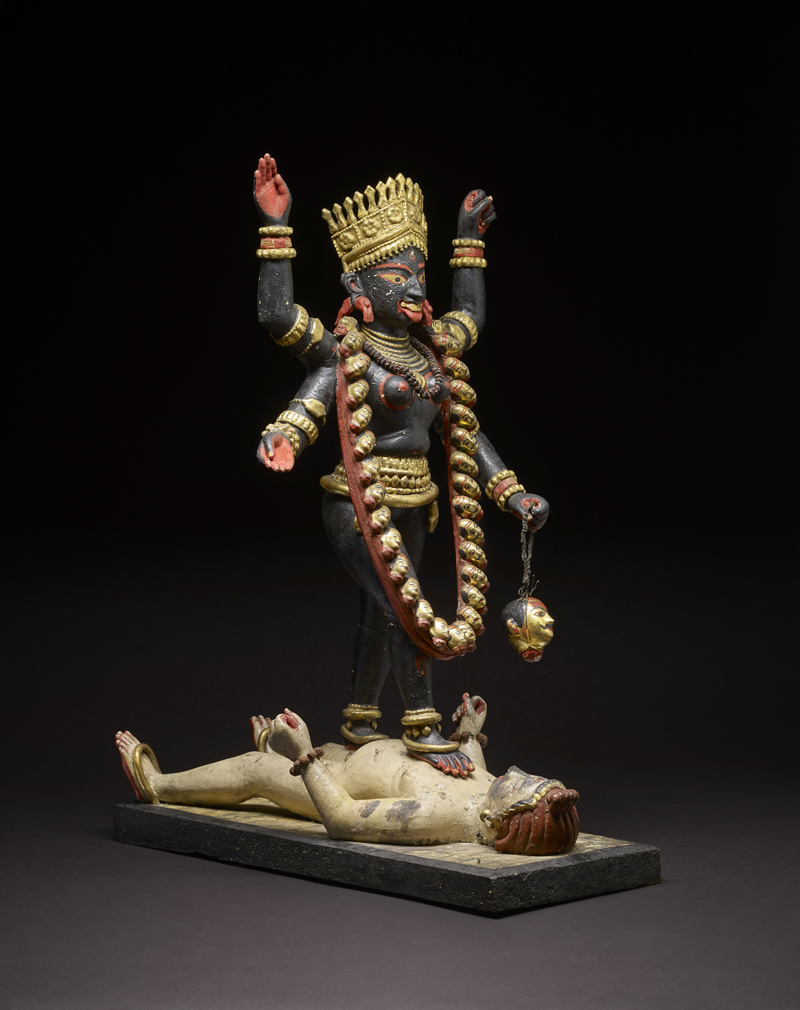

Against a background of social change that saw the emergence of new elites and an evolving landscape of patronage in eighteenth-century India, a decline has been detected in the practice of earlier, more exclusive, and caste-based forms of worship in favour of increasingly inclusive celebrations.Footnote 3 Many of these were funded by public subscription, with prominence given to tableaux of deities attended by human devotees. Frequently (but not exclusively), models in unfired clay provided a centrepiece for such celebrations. It seems likely that these called on long-established traditions of secular modelling that have remained undetected due to the ephemeral nature of the material. Certainly, their popularity was boosted by the intervention of one important patron whose name is invariably linked with the type: Maharaja Krishnachandra Roy (1728–1783) of Kishnaghur (Krishnanagar). In the mid-century he encouraged the settlement of potters from elsewhere in Bengal at Kishnaghur,Footnote 4 with the specific intention that they should produce clay figures to supply religious needs. Here the potters-turned-modellers not only found new markets but developed new skills in representing human and supernatural forms on a variety of scales, from miniature to life-sized.Footnote 5 Perhaps the best-known representatives of the type today are the large-scale figures of the Durga puja, attended by a varying cast of supporting characters, which continue to be produced anew each year and are consigned to the water at the end of the festivities, where the unfired clay returns to nature.Footnote 6 Other deities were similarly venerated: representations of Kali, for example (Figure 2), continue to be manufactured for the annual Kalipuja before being committed to the water where again they dissolve.Footnote 7

Figure 2. Figure of Kali striding over the recumbent Śiva. Kali wears her conventional garland of human skulls and carries a severed head. Painted clay, the crown and ornaments gilded. Height 53 cm. Kishnaghur [?]. Source: The British Museum, London, inv. no. 1894.2-16.10. ⓒ The Trustees of the British Museum.

The meticulously realistic secular figures that have come down to us seem to be representative of an early move away from production for purely devotional purposes to one in which skills that were developed in the field of modelling were turned to representing contemporary secular society. The clientele for such figures must surely have overlapped initially with that for the ritual pieces, but clearly it expanded at an early date to include European buyers. The accounts of early English travellers included here show that many of these purchases originally fed a demand for tourist souvenirs, but the capacity of the figures to represent the diversity of Indian society quickly became apparent to government administrators and others. It was certainly a novel form of documentation and illustration, whose further success on the international exhibition circuit (discussed below) must have gratified those who first recognised their potential in this respect.

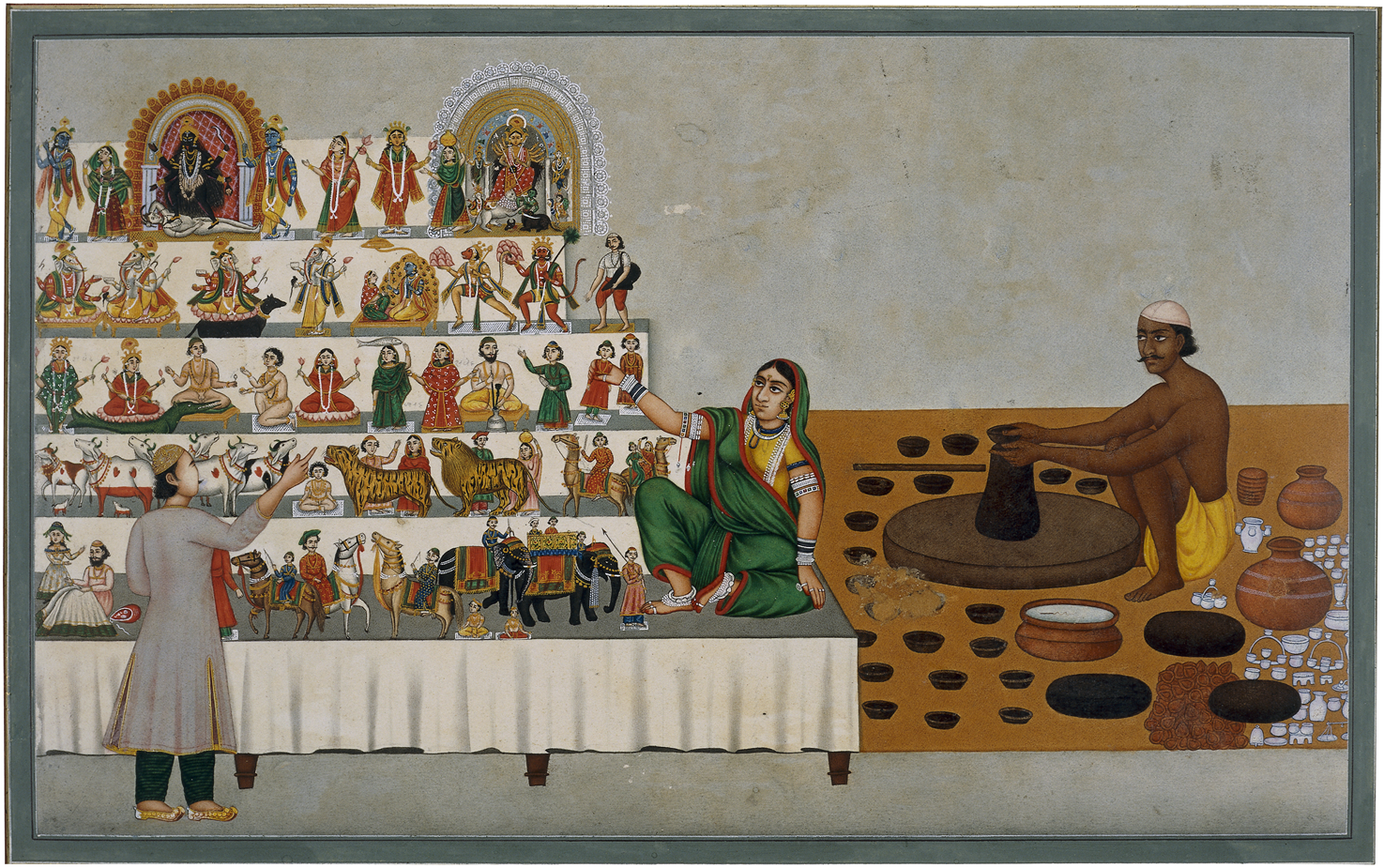

While Kishnaghur presents an exceptionally well-documented case-history for the development of clay modelling from minor craft to sizeable industry (and indeed has come to be regarded almost as the type-site for items produced by this technique), it was by no means the only centre of production. While no individual promoters of the stature of Krishnachandra Roy can be found elsewhere, a number of urban centres experienced significant growth in the eighteenth century under newly established elites; these included wealthy landholders and the mercantile middle class, the Maratha peshwas of Poona and the nawabs of Awadh. They too participated in the promotion of cultural practices that aimed to forge a sense of communal identity, among which newly developed devotional programmes employing ephemeral objects like the clay models played a prominent role. Likewise, the high levels of skill developed in the name of religious observance were soon extended to the production of the purely secular figures that form the focus of this article (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A market trader selling models illustrating religious and secular subjects, circa 1870. Tentatively attributed to Siva dyal Lal, Patna or Varanasi; neither of these cities is recorded as a production centre for the clay figures discussed here, but the image is uniquely valuable in the record it supplies of the popular trade in these figures. 26.5 × 39.8 cm. Source: The British Museum, London, inv. no. 1948,1009,0.156. ⓒ The Trustees of the British Museum.

One immediately striking fact concerning the models in question is that their production seems not to have been evenly distributed over the whole of the Indian sub-continent but was, to some degree, concentrated in a limited number of towns or cities. This stands in contrast to the widespread manufacture of (kiln-fired) terracotta figures produced for devotional or ornamental purposes, or as toys.Footnote 8 A few sites appear to predominate: as well as Kishnaghur in West Bengal on the eastern side, a clutch of centres is identifiable at Poona (Pune), Belgaum (Belagavi), and Gokak in the west; Lucknow is also a source of clay figures of a particular kind, on which see further below. Less well known (but clearly indicated by the India Museum collection) is that some production also took place further south, within the Madras presidency of the East India Company, a phenomenon that remains to be investigated in greater depth. Also in need of further research is the detailed nature of the social patterns that favoured production in these particular centres but not in others.

Production centres and their typologies

In the continuing absence of a wide-ranging and detailed survey of securely provenanced surviving figures, the following notes must be regarded as provisional. The field is open for further research and the remarks provided here on the production centres established so far—based on the largely lost collection of a single museum—can provide only a tentative starting point.

Typical Kishnaghur figures have been characterised as being modelled over a metal armature fixed in a rectangular base.Footnote 9 They adopt convincing poses, are painted in naturalistic colours, and are finely modelled with animated expressions. Hair may be represented by wool or jute and the figures are clothed in appropriate textiles. Like the religious images already mentioned, the figures are traditionally not kiln-fired but are simply dried in the sun; as a result, they are fragile and prone to cracking—a characteristic that must certainly have contributed to their very high casualty rate.

These comparatively sophisticated features immediately separate the Kishnaghur products from those of Poona, which are characterised by a more limited range of poses and less animated postures. They tend to rely for their individuality on a high level of finish to their anatomy (occasionally stretching to include body hair), clothing, and accoutrements. Among the latter, tools, for example, are made of materials corresponding to their full-sized prototypes. Characteristically, these clay figures are said to be moulded over a wooden rather than a metal armature and to stand on a turned wooden base. Henry Moses, attending a Durga festival in Poona in the mid-eighteenth century, noted many stalls there selling such figures, and by the 1840s permanent shops had been set up to supply them.Footnote 10 A decade or so later Mrs Hervey, an inveterate traveller, purchased about 30 examples representing ‘the various classes of natives, parsees, servants, tradesmen and fakirs’ as well as ‘idols’ and animals, all for 16 rupees. By 1880 the trade—whether catering for religious celebrations or tourist souvenirs—was estimated to be worth 10,000 rupees a year to Poona's municipal corporation.Footnote 11 Those sent to London to the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in 1886 were said to be ‘distinguished for their truthful modeling and life-like representation of the large variety of races inhabiting the Bombay Presidency, each race having its dress and turban distinct from another’.Footnote 12

A number of other centres of production are signalled less widely within the India Museum lists. Gokak, for example, a town in Belgaum district to the south of Poona, evidently was a recognised source of figures. Among those sent to the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Gokak products were judged ‘less perfect in point of execution than the Kishnaghur clay figures, but still most interesting’.Footnote 13 Although the range of figures produced at Gokak seems fairly standard, they were said to have been made there purely to order and did not normally form part of a regular trade.

Condapilly (Kandapalle), a remote and rather unpopular hill station as far as the British were concerned, lying in the Northern Circars—inland from Madras (Chennai)—seems not to have been recorded elsewhere as a source of figures of this kind, beyond an oblique reference in Henry Morris's Descriptive Account of the Godavery District in which he mentions that ‘Curious toys, figures, and artificial fruits are made by a family of the Muchi caste at Nursapore. They are rather larger, but quite as lifelike, as the similar figures manufactured at Condapilly in the Kistna district.’Footnote 14 Both Condapilly and Nursapore (Narsapuram) were represented in the India Museum collections.

A number of figures attributed to Madras may have been acquired within the city but could equally have come from one or other of the centres already mentioned, which lay within the Madras presidency. The same difficulties of precise location apply to the many figures from Belgaum, which may have been a production centre in its own right or the figures may have come from Gokak which, as mentioned, lies within Belgaum district.

A rather different trajectory has been traced for the clay models known to have been produced in Lucknow—a distinction so fundamental as to merit their separate consideration from the others examined here. Clay modellers were certainly to be found at work there in the 1700s, as elsewhere, but when Nawab Asaf ud-Daula (1748–1797) conceived the idea of beautifying his palaces and gardens, he did so with the aid of imported Italian sculptors. In 1780 the city's most distinguished European resident, Claude Martin, formerly of the French and later of the English EIC, commissioned local carvers to produce sculptures in stone and in stucco for his estate, also executed in classicising European style. So influential were these developments that the output of some of the Lucknow clay modellers—even those working at the small scale considered here—came under European neo-classical influence.Footnote 15 Surviving examples of their products, formed over a metal armature, are distinguished by having their draperies entirely modelled in clay, carved and tooled while it remained ductile; from the 1850s they were further marked by being painted in full colour.Footnote 16 A further significant difference, as observed by Susan Bean,Footnote 17 is that most of the Lucknow figures are of fired clay (for which a metal armature would have been a prerequisite). The implication is either that they may belong to a separate manufacturing tradition, or it may be that the known examples simply belong to a later phase of production when firing became more prevalent (see further below).

A degree of specialisation between these various producers, both in subject-matter and in technique, was detected by H. H. Cole in his Catalogue of Indian Art, where he also extends the range of production centres:

At Poonah, in the Bombay Presidency, all kinds of models are made to illustrate the castes and trades of Western India, as, for instance, dyers, singers, and musicians, oil-sellers, dancing or nautch girls, weavers, jewelers, merchants, all classes of domestic and State servants, women grinding corn, corn dealers, carpenters, shoemakers, blacksmiths, butchers, barbers, tailors, potters, Parsees, native officials, water-carriers, sweepers, &c. At Lucknow models are also made of figures, but the best are those representing different kinds of fruit. Models of the latter description are also made in Calcutta, Agra, and Jaloun in the North-west Provinces. The models of fruit made at Gokak, near Belgaum, are celebrated throughout India.Footnote 18

The above remarks referred principally to figures made in clay, but alongside these there existed a parallel series fashioned in wood, similar in the range of types encountered but invariably with details of costume and hair applied solely in paint: one such figure from Belgaum from the India Museum collection is illustrated in Figure 4. All must have borne a strong resemblance to those in clay produced in the same city.

Figure 4. Model in painted wood from the India Museum, illustrating cleaning cotton with a foot-roller and conforming to the same aesthetic as the clay models discussed here. Height 16.5 cm. Belgaum. Source: V&A, inv. no. 259(IS). ⓒ Victoria and Albert Museum, London, inv. no. 259(IS).

Figures in the India Museum collection

The broad characterisation of the industry provided above is (so far as we can tell, given their largely vanished state) borne out by the models that formed part of the India Museum collections. These are numbered 1 to 274 in the first part of the two-section catalogue printed in 1880 to mark their transfer to the South Kensington Museum, plus a further 120 or so entries scattered through the second part.Footnote 19 They include some sizeable groups and tableaux, so that the total number of figures would have been considerably higher: one such group of 68 figures was ‘painted, in native costume’; another, a box with 40 ‘painted and draped figures’; a third, a box containing ‘15 perfect and a number of imperfect figures’; and a further set of 40 unclassified. It seems possible that some may reflect attempts to illustrate the diversity of India's population in terms of physical types or professions, or simply of dress. Other formal groupings were certainly arranged to illustrate themes—‘an Indian village and Court of Justice, with a European Judge, presiding for the purpose of promoting its dispensation’; and perhaps most impressively,

a kind of regal levee, at which a prince, sitting in front of a tent of crimson velvet, fringed with a massive bordering of silver-work, receives the homage of his ministers and chiefs, or perhaps his guests. The whole affair is of the most gorgeous description, blazing in gold, silver, and brilliant colours.Footnote 20

One of the most impressive tableaux surviving today (Figure 5), representing an indigo factory with some 100 figures at work on various tasks, was commissioned by T. N. Mukharji of the Bengal Civil Service (and also a curator in the Indian Museum in Calcutta), whose published works are cited here, for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886. It now forms part of the Economic Botany Collections at Kew Gardens. The maker is recorded as Rakhal Chunder Pal (1834–1911).Footnote 21

Figure 5. Model of a factory producing indigo dye (detail), produced by Rakhal Chunder Pal for display in the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 in London. The model, populated with over 100 figures, shows every stage in the production process, from the arrival of the indigo plants by oxcart to the finished product. 1.5 × 2.0 m. Source: Economic Botany Collections, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, inv. no. EBC 79733.

All the production centres already mentioned appear in the India Museum catalogue, with 56 entries relating to Kishnaghur, four to Lucknow, and nine to Poona. For Gokak, 16 entries are recorded. To these may be added a further 33 models assigned to Belgaum and 17 entries to Desnoor (Deshnoor), also in Belgaum district. More unexpectedly, there are 13 entries for South Arcot, 17 from Trichinopoly (Tiruchirappalli), and two from Condapilly—all within the Madras presidency which, at its greatest extent, stretched from coast to coast in the southern part of the sub-continent. A further 63 entries are given simply to ‘Madras’, but for the above reasons it is difficult to assign meaning and importance to them, except to say that southern India has hitherto been under-represented in discussions of this industry.

It may be noted that entries for other categories of material in the India Museum catalogue indicate that by the time of its authorship the collection had been heavily augmented by material which had not been collected directly in the course of fieldwork in India. It had, rather, arrived through the medium of the series of international expositions that followed in the wake of the Great Exhibition of 1851 (see below). Since few dates of acquisition are attached to the entries for unfired clay figures, many of them may have belonged to the period when indigenous production was already being influenced by external factors. Others mentioned below are likely to have been acquired from one or other of the international exhibitions in the 1850s and beyond. Undoubtedly, production for local consumption continued alongside this new market, but in the absence of the original material, the potential for further analysis or the construction of a chronology remains limited.

The seemingly alarming scale of the losses suffered by the figures and models needs to be seen in context. In the first place, the unfired state in which they were producedFootnote 22 meant that many of them were always doomed to self-destruction. Certainly, they would have been exceptionally vulnerable to damage during their peregrinations from India to London, to the several venues in which the India Museum came to rest in the course of its 80-year existence,Footnote 23 and in some instances during exhibition elsewhere, even internationally. Secondly, it seems clear that few of these would have been treasured for their own sake as works of art—even as folk art. In the museum and exhibition context they evidently functioned rather as props or visual aids—as means of representing the wide social themes or large-scale industrial and preparative processes that were at the heart of Britain's interest in the sub-continent and which would certainly have defied treatment in the cramped quarters of the India Museum. Added to that, the undoubted perception that they would have been infinitely replaceable, simply by sending a repeat order to the appropriate presidency, must go a long way to explaining the seemingly cavalier attitude to de-accessioning that took place in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Although the bulk of those listed in the catalogue are entirely anonymous as to their manufacture, a single name stands out—‘Joodoonath Pal’—but it is of real interest. The Pal family—Jadunath, his brother Ram Lal Pal, his nephew Bakkeswar Pal, and their neighbour and relative Rakhal Das Pal—were said by the 1880s to be the only modellers of real note then working in Kishnaghur, which we may take to mean the only ones considered as artist-craftsmen with a wide European market. Their work is represented by four models, now in Asian and African Studies at the British Library (Figure 6): representing a brahmin, two potters, and a tailor, they came to the library from the collection of Sir William Foster, registrar and historiographer to the India Office, and are said to have been brought to England first for the Great Exhibition. Jadunath Pal contributed life-size figures to the Amsterdam exhibition of 1883 and shortly afterwards was commissioned to illustrate the races of India with a set of models for exhibition at Calcutta.Footnote 24 The British Library's description of its models as from the ‘studio’ of Jadunath Pal is perhaps more apposite than it might at first appear: Jadunath (circa 1821–circa 1900) had attended the Government School of Art in Calcutta and also served as an instructor there. He and his family ‘repeatedly gained medals and certificates in most of the International Exhibitions’,Footnote 25 so his working practices as well as his style may well have been quite heavily imbued with European influence. While the Pals worked in a range of scales, some of the figures produced for exhibition by Jadunath were certainly life-sized, while his kinsman Rakhal Das was said to be the best artist in miniature scenes,Footnote 26 as represented in the India Museum. The producers of the hundreds of other figures, as might be expected, remain anonymous.

Figure 6. Figure of a potter applying painted decoration to his vessels; missing here are the paintbrush originally held in his right hand and a bowl from his left. Height 14.3 cm. From the collection of Sir William Foster. Source: The British Library, London, inv. no. Foster 1039. ⓒ The British Library Board.

The international exhibitions and the reception of models in Europe

Apart from the assembly of its own publicly accessible museum, the EIC contributed hugely to the 1851 Great Exhibition (its exhibits coordinated by John Forbes RoyleFootnote 27) and to several succeeding world fairs, generally overseen under the regime of the India Office by John Forbes Watson.Footnote 28 At all of these, the contextual role of the small-scale models is clear. One contemporary observer in 1851 enthused:

If the East India Company had conceived the idea of fitting up a large portion of the Exhibition Building with the machines and implements employed by the Hindoos, and had, at the same time, imported the native workmen to use them, and grouped Indians of every caste around as spectators, they could not have better succeeded in portraying the peculiarities of oriental costume and habits, than by exhibiting those interesting models in clay and wood, illustrative of many ceremonials and customs of a novel and characteristic description. They did not merely represent machines and men, but had so much life and sprightliness infused in their every attitude, that they looked more as if they were intended for models of manners.Footnote 29

Included among these displays were not only individual figures and small groups but also quite elaborate tableaux featuring multiple objects. The Reports of the Juries of the 1851 Exhibition single out for comment a contribution from a Mr Mansfield of the EIC's civil service, showing the encampment of a government collector on his tour of duty, which was populated by some 300 figures contributing in various ways to the scene. The potential of some models for the instruction of those who might be expected to bring about improvements to the Indian agricultural economy was also appreciated. Commenting on one group, including a representation of six oxen being used to raise water from a well, the authors of The Crystal Palace and its Contents observed that ‘this set of models might afford the means of a very useful and interesting lecture on the application of simple machinery to irrigation. To intending colonists such lessons would have great value.’Footnote 30 Among the awards made to the Company in 1851 was a prize medal for ‘Clay figures, representing the various Hindoo castes and professions, manufactured in Kishnagur’ (Figure 7), a selection of which made an appearance in the ‘illustrated cyclopaedia’ of the exhibition.Footnote 31 Following the exhibition, at least some of these were sold off, indicating that they were perceived to have fulfilled their essentially ephemeral function.Footnote 32

Figure 7. Figures from the India Museum exhibited at the Great Exhibition. Source: The Crystal Palace and its Contents, p. 101.

In 1855 the Company had a presence at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, about which we know rather less in detail, but a Christie's catalogue published two years later lists among the surplus material sold off by the Company in London after the exhibition ‘An elephant with a figure in a howdah, a sacred bull, a dog, various male and female figures, two horsemen and four figures carrying a palanquin’.Footnote 33

In 1862 it was again London's turn to host the international exhibition, installed on the western side of Exhibition Road. The Indian section there was arranged by Forbes Watson, whose Descriptive Catalogue of the Indian Department of the exhibition lists over 100 models, several of the entries being for multiple figures. Major groups illustrated the various ‘native classes, trades and professions’, most contributions being credited to the Government of India but with a sizeable number described as ‘Condapully figures’ from the Kistna district, exhibited by the Madras government.Footnote 34 In 1865, several models showing ploughing and harrowing are known to have been sent for exhibition in New Zealand.Footnote 35

Records of a further 55 models and figures in the South Kensington Museum's catalogue are annotated with the date 1867, suggesting (and in some instances specifically stating) that they formed part of the Exposition Universelle that ran in Paris from April to November in that year. A point of special interest in these is that many of the records also show a price in rupees (all modest, varying from 2 or 3 up to 18 rupees for a group of dancing girls and musicians), strongly suggesting that they resulted from a specific buying campaign undertaken with the exhibition in mind.

Others specifically mention the Vienna Universal Exhibition of 1873, for which Forbes Watson compiled a Classified and Descriptive Catalogue of the Indian Department.Footnote 36 Interestingly, some of the models there were by now being used to demonstrate ways in which traditional Indian practices had been superseded by industrial processes introduced from or inspired by Europe. There was, for example, a major display on the cotton industry in which use of the traditional foot-roller was included (see Figure 4). The only cotton shown, which had been prepared by the traditional method, was described, however, as having been ‘much injured by the foot roller’ and re-cleaned by another method, so that the models now carried new messages of obsolescence and the need for industrial reform.Footnote 37

Further agricultural models as well as model boats (in wood) travelled to Philadelphia for the Centennial Exhibition of 1876,Footnote 38 seemingly the last opportunity for the India Museum collection to contribute in this way. After it was dispersed in 1879, however, other figures continued to appear on the international exhibition circuit. They were prominent at Amsterdam in 1883. The Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 included 12 sets of life-size figures in clay or plaster scattered throughout the exhibition, each illustrating ‘typical’ peoples of particular regions: they included ‘a series of terra-cotta figurines, sketched in clay from living models, illustrating the working people of the Panjab’, mostly made by G. P. Pito of the Mayo School of Art in Lahore,Footnote 39 and a series of Andaman Islanders modelled by Jadunath Pal.Footnote 40 The Glasgow International Exhibition of 1888 featured 17 life-size models, again by Jadunath Pal.Footnote 41

The presence of these specially commissioned sets of images in clay calls to mind other forms of systematic survey that were by now being applied to documenting the ethnic diversity of the Indian population. Prominent among these are the plaster moulds of human features produced by the Schlagintweit brothers on the eve of the Uprising of 1857. Some 250 of these (plus hands and feet) had been completed by the time the unrest brought their survey to a premature end; zinc castings produced afterwards were then made available to the emerging body of ethnologists and to museums on a commercial basis.Footnote 42 Photography was similarly employed in large-scale surveys of this kind, one of the most important being The Costumes and People of India, published in eight volumes by the India Museum between 1868 and 1875, under the editorship of Forbes Watson and J. W. Kent.Footnote 43 While it cannot be claimed that the small-scale clay figures described here were ever produced with such a specific aim in mind, some of them clearly came to perform a comparable role once they entered the museum environment. In this context their attention to the details of dress, accoutrements, and practices as well as the physical appearance of their subjects became a matter of primary importance, although this did not please everyone.

The reception of the figures

While responses to the roles played by figures in the museum and exhibition context were universally appreciative, from an aesthetic point of view the critics proved ambivalent in their responses to them. Evidently they were willing to acknowledge the documentary role of the figures but adopted a rather lofty and often supercilious tone when judging these (essentially craft-based) products against the clay modelling traditions of European studio practice. This is perhaps most relevant in the case of the larger-scale figures which found themselves the object of direct comparison with European sculptures in the international exhibition setting, although at times it is difficult to tell whether large- or small-scale works are being cited.

The ambivalent position they occupied in this respect was partly due to what was described as the modellers’ ‘unhappy predilection for introducing pieces of real fabrics in the clothing; actual hair and wool in the figures; and in the accessories, straw and grass, &c’, which reduced the figures in the eyes of the critics to the level of ‘ingenious toy-making’.Footnote 44 Sir George Watt was similarly dismissive of these ‘toys dressed in actual clothes’.Footnote 45 George Birdwood was prepared to acknowledge the documentary role of the Lucknow figures—‘most faithful and characteristic representations of the different races … and highly creditable to the technical knowledge and taste of the artists’—but denigrated those espousing European influence, produced ‘in a very debased style, being modelled after the Italian work that is to be found all over Lucknow’.Footnote 46 By the time of the exhibition of Indian art at Delhi in 1903, however, Watt, the exhibition's director, was content to describe unequivocally the works of Bhagwant Singh, modelling master of the Lucknow Technical School (‘a modeller by caste and an artist by instinct’), as ‘a very instructive and realistic series of examples of Fine Art’.Footnote 47 Modelling in this sense had by now moved well beyond the milieu in which it had first developed in India. Both in the sub-continent and in England it found itself enmeshed in debates whose proponents advocated passionately for, on the one hand, the extension of access to European traditions through the government schools of art established in India from mid-century, or who bemoaned, on the other hand, the undermining of established Indian traditions by the imposition of alien aesthetic values derived from the (European) classical canon.Footnote 48

Although treated hitherto as primarily illustrative in intent, the representations of craftsmen at work, which constitute a large part of the surviving corpus, may also be seen in relation to the body of scholarship which, in recent decades, has concerned itself with the central role played by the figure of the craftsman in debates that followed in the wake of the international exhibitions of the later 1800s. Here the traditional crafts of India were perceived as imbued with an integrity born of generations of hereditary craftsmanship, a process characterised as biological as much as social by the likes of George Birdwood, but they were also seen as essentially in decline and under threat from Western industrialisation. This discourse was staged around a flood of visual representations of the craftsman at work—whether in the form of drawings, photographs, or illustrated publications, many of them issuing from the government art colleges in India. Initially epitomising the essential virtues of traditional forms of production, these compositions were gradually recruited into a more socially conscious narrative that sought first to highlight the damaging impact wrought by the aggressive Western assault on indigenous production and, ultimately, by the promotion of a nationalist agenda that called for the rejection of colonial influence and political control. Prominent among the authors who have articulated the visual dimensions of this trope are Saloni MathurFootnote 49 and Deepali Dewan.Footnote 50 Although neither author makes specific mention of the clay figures considered here, their characterisation of the common range of these images could apply equally to the craft figures produced in clay—the craftsman with his head bent as if concentrating on the task before him, his gestures and facial expression capturing the ‘the knowledge of traditional Indian arts … being transferred from the craftsman's body to the object he produces’.Footnote 51 And like the two-dimensional images—often regionally specific—that they discuss, the clay figures too were commonly displayed in the exhibition context alongside the products of the craft concerned.

Given these similarities and the degree of chronological overlap, the unfired clay figures considered here must in some sense have participated in that same visual trope, although the range of subjects extends far beyond the hereditary craftsmen who concern Mathur and Dewan. In fact, the extended range of everyday subjects—beggars, jugglers, water-sellers, and so on—would make it difficult to apply the workings of the mechanisms they describe to what we know of the deployment of the figures within the India Museum. Here there is every indication that the figures were used in the pursuit of a more narrowly drawn mercantile agenda, in which the influence of the critics, designers, and philosophers who engaged so closely with the aesthetic preoccupations of the South Kensington Museum were comparatively muted. No doubt the craftsman was seen here too as the repository of much traditional skill and knowledge,Footnote 52 but he was presented almost in an ethnographical mode—illustrative of the industries whose products he accompanied but lacking the evangelising role attributed to the drawings produced in the art school milieu.

Further light is cast on the roles played by figures of this type in Abigail McGowan's admirably insightful Crafting the Nation in Colonial India, which charts the emergence of an interest in viewing craft products in relation to both production methods and producers.Footnote 53 Much of this work was articulated in the commissioning of surveys and gazetteers that had the ultimate aim of characterising the productive potential of communities throughout British India. Of particular note here is the locating of these various initiatives, which McGowan illustrates with a display of clay models of artisans from the Victoria and Albert Museum (today the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum) in Bombay, in the two or three decades from about 1880. By this time the independent existence of the India Museum collections on which the present survey is based, had already been brought to an end and control of the objects had been transferred to the South Kensington Museum. While that particular collection became a closed archive from 1879 onwards, the role ascribed to the figures by McGowan marks a further chapter in the continuing evolution of the purposes to which these figures were recruited. Their long history, from their conception as adjuncts to religious ritual a century earlier, remains to be fully explored.

Plaster modelling

An increase in the use of plaster rather than clay as a modelling medium becomes increasingly apparent in the later nineteenth century. T. N. Mukharji attributes the introduction of plaster of Paris in this genre chiefly to Italian artists employed in the schools of art founded by the British.Footnote 54 This assertion finds support from Sir Edward Buck who writes, in the preface to the catalogue of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, that ‘the system for the first time adopted in connection with this Exhibition of reproducing work in Plaster of Paris seems likely to give prominence and encouragement to the plastic art of the country, since it will now be possible to meet any demand which may arise for such work with less risk of breakage and at much smaller cost’. Buck attributes its introduction specifically to ‘Mr J. Schaumburg, artist, attached to the Geological Survey Department of India’.Footnote 55 A group in plaster ‘representing “suttee”, &c., formerly exhibited at the Paris Exhibition, 1867’ suggests that this movement got under way at quite an early date in the history of the international exhibitions.

Modelling in clay remains a universal studio practice, the slow-drying medium allowing the artist or craftsman to mould and to modify the work until the desired form is reached. Plaster of Paris, by contrast is comparatively quick-drying: the process (involving a chemical reaction rather than merely desiccation) begins about 10 minutes after the powdered gypsum is hydrated and is complete within around 45 minutes. Rapid working is therefore essential, but the principal use of plaster of Paris has been in the production of casts: Buck's reference to the ‘reproducing’ of sculptural art implies that this is the function he had in mind, so the status of at least some of the works referred to remains ambivalent. Certainly there is no suggestion that any of the figures discussed here were cast rather than moulded.

The term ‘plaster’ further crops up in contexts suggesting that it was in much wider use in everyday society both in India and beyond, and that its use in modelling already had a lengthy history. For example, in the collection of Dr Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner—assembled in Central Asia, far from European influence and deposited in the India Museum—there were numerous heads, busts, and religious figurines, as well as a ‘group of grotesque figures’ from Takht-i-bahi, said to be of plaster. These would have dated from the early centuries ad. There are also numerous more recent figures in the collection which sound indistinguishable from those discussed here, except for their being identified as made of plaster. These include a ‘Native, with textile girdle and turban’, a ‘Warrior, with sword and shield’, a ‘Female, costume covered in tinsel’, ‘Dolls, twenty-three, plaster, dress[ed] in native costume’, and models of a loaf of bread on a plate and of fruit on a plate in painted plaster. Some of these are even from Kishnaghur—so strongly associated with the production of unfired clay figures—including a ‘Model of an oil mill, with bullock’, and two further figures of bullocks. These seem unlikely to be of the ‘Plaster of Paris’ mentioned specifically by Buck and are no doubt modelled in white clay, whether fired or otherwise.

Conclusion

The figures described here not only stand as representatives of a formerly vibrant minor industry but form an extraordinarily vivid record of many aspects of popular culture—from religious observance to craft activities, agriculture and transport, regional dress and ornament, and so on—as captured by those who lived and worked among their subjects and were well placed to observe them. Their enthusiastic adoption by the curators of Western exhibitions and displays is reflected in the large numbers of figures alluded to in the historical record, adding further dimensions to their erstwhile roles. Perhaps no other institution did more to influence the latter development than the India Museum: significantly, following the transfer of the collection in 1879 to the South Kensington Museum—dedicated to matters of art and design rather than ethnology—we hear no more of the figures beyond the record of their progressive disposal, occasionally sold at auction but more frequently written off due to their having self-destructed with the passage of time. The ephemerality that formed an essential aspect of their earliest development reasserted itself inexorably, placing a limit on the collection's capacity to contribute at more than a documentary level to continuing research into these fascinating but elusive artefacts.

Acknowledgements

The outlines of this article were compiled during the author's Andrew W. Mellon visiting professorship at the Victoria and Albert Museum's Research Institute, examining the history of the East India Company's museum collections; see ‘The India Museum Revisited’ website at https://www.vam.ac.uk/research/projects/the-india-museum-revisited. Grateful thanks are due for help in kind and for comments and criticism of a draft of the present text to Dr Susan Bean, Chair of the Art and Archaeology Center, American Institute of Indian Studies; T. Richard Blurton, former curator for South Indian and South East Asian collections, the British Museum; Dr Deepali Dewan, Senior Curator, Global South Asia at the Royal Ontario Museum; Dr Mark Nesbitt, Curator, Economic Botany Collection, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; and Dr Malini Roy, Head of Visual Arts at the Asia and Africa Collections, the British Library. The insightful comments of JRAS's anonymous referees were also extremely helpful and have been incorporated at intervals throughout the text.

Conflicts of interest

None.