Introduction

Third-wave variationist sociolinguistics has drawn attention to the role of language style in speakers’ projection of complex identities, and to how speakers establish indexical links between stylistic practices and social meanings (e.g. Podesva Reference Podesva2007; Eckert Reference Eckert2008, Reference Eckert2012; Zhang Reference Zhang2008; Pratt & D'Onofrio Reference Pratt and D'Onofrio2017; Hall-Lew, Moore, & Podesva Reference Hall-Lew, Moore, Podesva, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021). High performance offers good opportunities for such analysis because it embodies cultural values and frequently makes use of the stylization of linguistic resources to form a performance style (Johnstone, Andrus, & Danielson Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006; Bell & Gibson Reference Bell and Gibson2011; Coupland Reference Coupland2011; Pratt & D'Onofrio Reference Pratt and D'Onofrio2014; Lin & Chan Reference Lin and Chan2021). Such verbal performance often involves building on existing social meanings to do ideological and indexical work by using certain linguistic features to reflect local normativity, convey social information, and construct performers’ identities. Studies in hip hop linguistics also have found that rappers’ language style and constructed identity in the performance of rap music involve indexical links to African American English (AAE) features, racialized categories, and hip hop cultural traditions (Alim Reference Alim, Finegan and Rickford2004, Reference Alim, Samy Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook2009; Guy & Cutler Reference Guy and Cutler2011; Eberhardt & Freeman Reference Eberhardt and Freeman2015). While the use of AAE combined with local linguistic resources and nonstandard dialectal resources to construct hip hop authenticity outside the USA is well documented (Androutsopoulos & Scholz Reference Androutsopoulos and Scholz2003; Pennycook Reference Pennycook2007a), other local creative stylistic practices associated with hip hop cultures remain understudied. This study expands the analysis of stylistic variation in hip hop performance by investigating how various phonological features of Beijing Mandarin (BM) coherently construct hip hop affiliated identities in the ideological and cultural frames of the relatively new emerging Chinese hip hop community.

Hip hop linguistics has largely focused on the appropriation of African American cultural forms by white people and on practices of translocalization that constitute the Global Hip Hop Nation (Alim Reference Alim, Sinfree Makoni, Ball and Spears2003), mainly within the Anglosphere and in terms of global Englishes and cultural reterritorialization (Cutler Reference Cutler2010; Eberhardt & Freeman Reference Eberhardt and Freeman2015; Sawan Reference Sawan2021). However, worldwide hip hop culture is more than a byproduct of the spread of English or a cultural representation of tensions between globalization and localization. It involves ‘a compulsion not only to make hip hop locally relevant but also to define locally what authenticity means’ (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2007b:98). The mantra of authenticity—of ‘keepin’ it real’—in hip hop culture drives global youth to reproduce their local identity through employing nonstandard varieties or minority languages in their music (Androutsopoulos & Scholz Reference Androutsopoulos and Scholz2003; Pennycook Reference Pennycook2007a; Barrett Reference Barrett2012). Thus, hip hop authenticity has come to be interpreted as being true to one's roots in local contexts, cultures, and languages.

Connecting ‘street’ language styles to rappers’ street-conscious identity has recently emerged as a means for non-African Americans to authentically identify with the hip hop community (Stæhr & Madsen Reference Stæhr and Madsen2017; Cotgrove Reference Cotgrove2018). As Alim (Reference Alim, Sinfree Makoni, Ball and Spears2003:51) asserted, ‘the streets have been and continue to be a driving force in hip hop culture’. Alim described a ‘code of the streets’ in the context of the United States, which, linguistically speaking is AAE, but that also includes ‘both members and the sets of values, morals, and cultural aesthetics that govern life in the local streets’ (Reference Alim, Sinfree Makoni, Ball and Spears2003:45). Many non-African American rappers do not attempt to use AAE as a resource to associate themselves with hip hop (Stæhr & Madsen Reference Stæhr and Madsen2017; Cotgrove Reference Cotgrove2018). But if Alim's concept of ‘the code of the streets’ is extended to the global context, the fact that ‘the street’ and local ‘street’ language vary from community to community makes it important for hip hop artists to consciously engage with local linguistic and cultural resources in their music. This study on the community of Beijing hip hop—a subgenre of Chinese hip hop—provides additional evidence that global youth use creative linguistic practices to draw on local characterological figures and culturally associate themselves with the ‘street’.

Rap music entered the Chinese mainland's underground music scene through dakou CDs and audiocassettes illegally imported from the United States in the 1990s. It became mainstream only after the immense success of an online rap competition show The Rap of China in 2017. However, rap music was the target of two censorship bans before and after the show. In 2015, the Chinese Ministry of Culture blacklisted a hundred hip hop songs online for ‘trumpeted obscenity, violence, crime or harmed social morality’ (Han Reference Han2015). The second ban was never officially announced. However, in January 2018, a blurry screenshot circulated on the internet showing an official of the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT) announcing a new ‘hip hop ban’ in a meeting (Xinlang Yule 2018). The gist was that programs or reality shows on Chinese media should not invite guests who were tattooed or representatives of hip hop culture, subcultures, and ‘dispirited’ cultures (i.e. sang wenhua; the term connotes negative attitudes toward traditional notions of success, e.g., a decent job, fame; Dukoff Reference Dukoff2018; Luo & Ming Reference Luo and Ming2020). This ban followed a series of scandals involving contestants on The Rap of China. For example, one co-winner, PG One, was accused of having an affair with a well-known married actress; shortly after that, one of his lyrics was criticized as promoting drug-related culture and misogyny, and some of his fans overreacted to such criticism by cyberbullying other netizens. PG One's songs then were removed from every platform in the Chinese mainland. Official or not, these bans unquestionably influenced Chinese rap music's direction; for instance, it is widely believed that several rappers who have participated in mainstream reality shows since 2018 can do so only because they strictly follow censorship rules.

Given this backdrop, artists have developed various styles at different stages of Chinese hip hop's development in order to circumvent censorship while constructing authentic hip hop identities. This study investigates the changing scene of Chinese rap music by focusing on the community in Beijing, which is commonly known as the Chinese mainland's hip hop capital. I present here an analysis of two generations of Beijing-born rappers’ stylistic variation to explore how local rappers use four BM phonological features—rhotacization (i.e. -er suffixation), lenition of retroflexes, interdental realization of dental sibilants, and palatal fronting (so-called ‘feminine accent’)—to style their personal identities and maintain the street-conscious identity of hip hop performers. The analysis examines the creative use of these four linguistic variables and the process in which two characterological figures, Jing youzi (the Beijing Smooth Operator) and hutong chuanzi (the Alley Saunterer), are incorporated into hip hop culture. I argue that the use of the BM features in rap music not only reinforces preexisting indexical links between phonological features and local social character types, but also constructs Chinese rappers’ styles through multiple indexical paths. In their stylistic innovation, Chinese rappers use their agency to reshape these BM features’ social meanings and link them to hip hop ideologies, such as street-wisdom, to open up new possibilities for cultural alignment with street credibility. This study thus supports the call for researchers on style to move beyond single features to examine semiotically coherent packages of co-occurring features (Pratt Reference Pratt2020; Maegaard & Pharao Reference Maegaard, Pharao, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021), but also underlines how a style-dependent indexical field is dynamically shaped when agents actively engage in bricolage, picking out certain stylistic elements from the arrays associated with existing local social meanings.

High performance, indexicality, and iconicity

In the broadest sense of performance, all speakers constantly use language to perform identity, and our everyday language use is always performative. However, this article focuses on high performance, meaning ‘public scheduled events, typically pre-announced and planned’ (Coupland Reference Coupland2007:147). Coupland (Reference Coupland2007) drew this distinction between mundane performance and high performance to study certain highly stylized depictions of enregistered varieties. Although terms such as verbal art (Bauman Reference Bauman1977) or staged performance (Gibson & Bell Reference Gibson and Bell2010) describe similar occasions of language use, I use the term high performance to highlight the use of stylized utterances for projecting identities or personae derived from well-known identity repertoires.

Stylistic variation and meaning in high performance have attracted considerable interest since Trudgill's (Reference Trudgill1983) research on British pop bands’ use of phonological features associated with Americanness. Trudgill's and some other early work in this vein (e.g. Simpson Reference Simpson1999) basically took a ‘territorial-indexical’ perspective (Coupland Reference Coupland2011:574). This approach seems to consider vernacularity in high performance to index only place, rather than the entire sociocultural background embedded in that place or a certain dialect's or accent's association with performance genres. More recent work has focused on the self-aware and reflexive nature of high performance, extending Bauman's (Reference Bauman1977) notion of ‘cultural performance’, to explore the relation between indexically loaded linguistic variables (such as accent and dialect) and performed identities or relevant personae (Johnstone Reference Johnstone2011; Carmichael Reference Carmichael2013; Pratt & D'Onofrio Reference Pratt and D'Onofrio2017).

Indexicality is an extremely useful paradigm for investigating connections among linguistic features, styles, and social meanings. The notion emerged from semiotics, was taken up by linguistic anthropology, and was adapted by Eckert (Reference Eckert2008) for use in third-wave variationist sociolinguistics. A crucial concept in this framework is Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2003) orders of indexicality, which describes how indexicals function at multiple levels, displaying different relationships between linguistic forms and social meanings, and being continually reconstrued in ideological moves. Silverstein argued that n-th order indexicality is correlated with sociodemographic identities, such as region and class, when indexicals are assigned ‘an ethno-metapragmatically driven native interpretation’ (Reference Silverstein2003:212). These n-th order indexical values are available for continually reinterpreting relations between linguistic forms and social meanings in ‘always already immanent’ n + 1st order indexicality (Reference Silverstein2003:194).

Drawing on Silverstein's (Reference Silverstein2003) framework, Johnstone et al. (Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006) assigned hierarchical values to orders of indexicality to exemplify how a set of linguistic forms became enregistered as ‘Pittsburghese’ through social and geographical mobility. In such processes of dialect enregisterment, linguistic features become associated with speech styles as indexing certain character types and ranges of social meanings (Agha Reference Agha2003, Reference Agha2007; Johnstone & Kiesling Reference Johnstone and Kiesling2008). By contrast, in order to capture the fluidity of different levels of social meanings, Eckert's (Reference Eckert2008:463) concept of the indexical field focuses more on ‘the ideological embedding of the process by which the link between form and meaning is made and remade’. Much work adopting the indexical field approach explores the malleability of social meanings of one linguistic variant and the ideological associations among n-th order indexical values and n + 1st order indexical values (e.g. Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Moore & Podesva Reference Moore and Podesva2009; Walker, García, Cortés, & Campbell-Kibler Reference Walker, García, Cortés and Campbell-Kibler2014).

More recent studies engaging with style and persona construction have highlighted the complexity of indexical fields (e.g. Calder Reference Calder2019a; Drager, Hardeman-Guthrie, Schutz, & Chik Reference Drager, Hardeman-Guthrie, Schutz, Chik, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021; Maegaard & Pharao Reference Maegaard, Pharao, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021; Wang Reference Wang2022). For instance, Maegaard and Pharao's (Reference Maegaard, Pharao, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021) work on social meanings associated with fronted (s) in the street and modern styles of Copenhagen Danish led them to suggest that the indexical field may be not only the property of one linguistic variable but also of a certain style. If style is ‘a clustering of linguistic resources, and an association of that clustering with social meaning’ (Eckert Reference Eckert, Eckert and Rickford2001:123), a style-based indexical field can contain indexical values for a variety of ideologically related features. Drawing on these ideas, the current study attempts to capture how Beijing rappers do style work and form new associations among social meanings through engaging with a cluster of local linguistic variables linked to a broad indexical field.

An indexical field's complexity is further reflected in different indexical paths resulting from the indeterminacy of social meanings (Hall-Lew et al. Reference Hall-Lew, Moore, Podesva, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021). One recent line of research has turned attention to the role of phonetic iconicity, or sound symbolism, exploring the semiotic processes in which indexical relationships become iconic ones (Calder Reference Calder2019b; Drager et al. Reference Drager, Hardeman-Guthrie, Schutz, Chik, Hall-Lew, Moore and Podesva2021). Perceived sensuous qualities of linguistic forms, or ‘qualia’, such as smoothness and fierceness, gain an association with human qualities (Gal Reference Gal2013; Calder Reference Calder2019b; D'Onofrio & Eckert Reference D'Onofrio and Eckert2021). As some phonetic sociolinguistic variables are both indexical and iconic (e.g. the voiceless anterior sibilant /s/ in Calder Reference Calder2019b), speakers can draw on the ideological connection between a linguistic feature and certain personal qualities to construct styles that enact social types or personae.

Similarly, in musical performance, a performer can exploit iconicity and sound symbolism by, for example, manipulating rhythmic structures with instrument-like vocal incursions, using the voice to recreate sound effects, and linking the qualia of the voice itself to the performer's personal qualities (Feld, Fox, Porcello, & Samuels Reference Feld, Fox, Porcello, Samuels and Duranti2004; Coupland Reference Coupland2011; Gal Reference Gal2013; Wang Reference Wang2022). Through the process of rhematization, in which an ideological connection is established by construing a sign or an index as an iconic representation of an object, phonetic resources can acquire indexical values related to musical expressiveness and further contribute to the corresponding personae situated in a given musical genre.

While little prior work on hip hop performance or rap music has paid attention to the sensuous qualities of voice, Wang (Reference Wang2022) investigated the use of fronted palatals (j, q, x) by Beijing-based rappers, who exploit these sounds’ resemblance to the percussive or rhythmic record scratch sound effect, iconic in hip hop music, which DJs create by manipulating vinyl records on turntables. While the previous social meaning of this BM variable is related to femininity (i.e. ‘feminine accent’) and has been linked to an early twentieth century Beijing secondary school girl persona in Chinese sociolinguistics (Hu Reference Hu1988), Chinese male rappers use the sharp and harsh quality of fronted palatals along with other semiotic features of hip hop performance to evoke new social meanings related to violence, masculinity, and toughness. In this way, Chinese rappers build musical and cultural connections to construct their hip hop authenticity and participate in the global hip hop community. This innovative use of a gender-related BM variable as a sound effect is further discussed in the current study's investigation of a generational difference among Beijing-born rappers.

Beijing-flavor rap music

This article discusses Beijing hip hop, or more specifically, Jingwei(r) shuochang ‘Beijing-flavor rap music’. Traditionally, shuochang and quyi refer to forms of sung storytelling accompanied by traditional Chinese musical instruments. Now, however, shuochang (but not quyi) specifically means rap music in the Chinese context. Jingwei(r) and Jingqiang (Beijing accent) point to a distinctive Beijing style that includes the local culture, speech, and cuisine (Zhang Reference Zhang2008). Jingwei shuochang, as a subgenre, features the distinctive Beijing accent and embraces ‘old school’ hip hop, referring to both, in the global context, the simpler techniques of rap music produced in the late 1970s to early 1980s, and, in the Chinese context, to the era of rap as an underground phenomenon, in which Beijing was central.

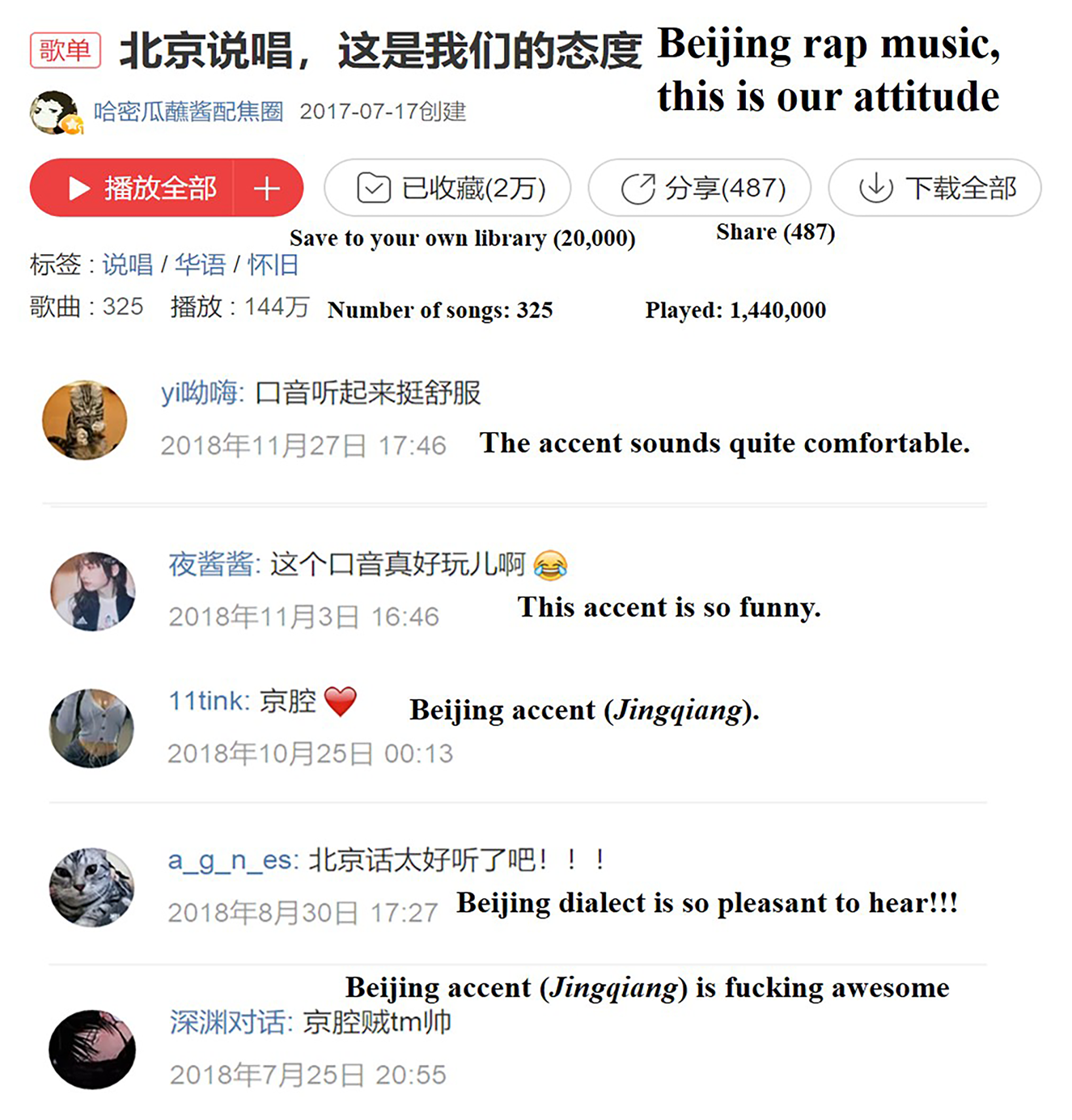

Searching for the key words Beijing shuochang and Jingwei shuochang on two mainstream Chinese online musical platforms, NetEase Cloud Music and QQ Music (similar to Spotify), yields a range of playlists whose names incorporate these phrases, many of which have been played by thousands of users. For instance, in 2022, a playlist named ‘Beijing rap music, this is our attitude’ had been played over one million times and saved to more than twenty thousand users’ libraries. The platforms allow comments, and some users offer metalinguistic observations on the typical Beijing accent of the songs, such as ‘Beijing dialect is so pleasant to hear’ and ‘Beijing accent (Jingqiang) is fucking awesome’ (Figure 1). While these comments do not pinpoint specific BM features as indexes or icons in Beijing-flavor rap music, they do reveal folk perceptions of a well-established indexical link between Beijing vernacular speech/Beijing accent, the artists’ origin or regional association, and the subgenre. Beijing vernacular speech has long been ‘one of the most salient and shared devices profusely used to produce the unique “Beijing flavor”’ (Zhang Reference Zhang2008:205) in other arts, including other musical genres and literature. This study investigates how the Beijing accent became ideologically linked with rap music and whether this specific stylized speech forges a linguistic-cultural connection with ‘the streets’ or, broadly speaking, with hip hop authenticity (Cutler Reference Cutler2003). To do so, it examines when several specific linguistic features of BM are chosen by Beijing rappers, what social meanings are attached to them, and how, as an enregistered variety of Chinese, this urban vernacular aligns with this musical genre.

Figure 1. Most-played Beijing rap playlist on NetEase Cloud Music, with sample comments.

Linguistic variables in Beijing Mandarin and their social meanings

Zhang (Reference Zhang2005, Reference Zhang2008, Reference Zhang2018) documented the enregisterment of several BM features, such as rhotacization, lenition, and interdental realization of dental sibilants, in ‘Cosmopolitan Mandarin’, and further discussed these features’ association with two local identities. Her work illuminates how the semiotic saliency of these phonological features represents an authentic Beijing style and connects with region-specific characterological figures. As an emblem of Beijing vernacular style, rhotacization, or the so-called ‘heavy r-sound’ comprises two features: adding the suffix -er to the syllable final (commonly known as erhua among Chinese speakers), and consonant rhotic lenition, that is, the lenited realization of retroflex obstruent initials [tʂ, tʂʰ, ʂ] as the approximant retroflex [ɻ] (Chao Reference Chao1968; Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst2012; Zhang Reference Zhang2018). Zhang (Reference Zhang2008) argued that in BM, both features, but particularly the extensive use of rhotacization of syllable finals, have a metalinguistic association with ‘smoothness’, and are identified with what she named the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ persona—a salient Beijing male character type involving a cluster of sociocultural attributes centered on street smarts and worldly wisdom. While lenition is less salient than erhua in casual speech, the lenited realization of retroflex obstruent initials is often described and perceived as ‘being glib, talking faster and swallowing sounds’, and further linked to smoothness as well (Zhang Reference Zhang2018:72). In the current study, ‘rhotacization’ refers only to erhua, while ‘lenition’ refers to the lenited realization of retroflex obstruent initials.

Zhang (Reference Zhang2005, Reference Zhang2018) also traced the social meaning of the interdental realization of dental sibilants to another local male persona, the ‘Alley Saunterer’, or hutong chuanzi. Hutongs, a type of traditional Beijing street with a history of many centuries, are narrow alleys running between main streets to form residential neighborhoods. The hutongs are enclosed by rows of siheyuan, quadrangles of houses that share a courtyard. Hutongs are seen as representing the daily life of ordinary people in Beijing. While they are disappearing in the face of urbanization and cultural changes, the hutongs, along with what is seen as the hutong culture and an indigenous Beijing lifestyle, retain high cultural value. The term hutong chuanzi captures the persona of a local Beijinger who is ‘feckless and walks about in the alleys, waiting for something to happen’ (Zhang Reference Zhang2018:71). Descendants of families who may well have been residents of the capital city for several generations, these lao beijingren (lit. ‘old Beijing people’, meaning people with deep roots in Beijing) who live in hutongs are considered ‘the indigenous Beijingers of the metropolis’, in part because they are likely to be less mobile than other Beijingers due to their socioeconomic class and educational background (Liu Reference Liu1985:122). These two quite distinct urban male personae, the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ and the ‘Alley Saunterer’, are closely associated with the street life and street wisdom of Beijing. This existing enregisterment enables this study to explore how Beijing-born rappers recombine locally available linguistic resources and take advantage of existing indexical connections to construct a streetwise rapper persona in high performance. In addition, the study considers the BM linguistic variable of palatal fronting, or ‘feminine accent’, which has been recontextualized by younger generation male rappers to embody masculinity in their music.

Method

Data selection

Ten Beijing-born rappers were chosen for this study. None had lived elsewhere, and all were males, as the community includes very few female performers. Chinese rappers can be divided into three generations according to their performance style, active period, and debut years. This study includes five performers from the second generation and five from the third generation. The first generation was excluded due to limited comparability; it refers to some Beijing-born pop singers, including several who released an album named China rap in 1993 (Fan Reference Fan2019), but their style is closer to traditional Chinese shuochang than to rap music (Amar Reference Amar2018). The five second generation rappers were born in the 1980s, debuted during the first decade of the twenty-first century, and were active during Chinese hip hop's underground era, before the music became available on the internet. The five third generation rappers were born in the 1990s and debuted between 2010 and 2015; they have been active since the hit competition show in 2017, as rap became increasingly mainstream and popular among younger generations.

Twenty verses in total were chosen for the analysis based on their popularity and themes. A preliminary observation of music content indicated that a considerable number of songs written and performed by Beijing rappers are related to Beijing culture and daily life. Many of these songs mention Jing or Beijing in the title, such as Beijing Wanbao ‘Beijing evening news’ and Beijing Hua ‘Beijing Mandarin’. Other songs’ themes cover general hip hop topics, such as brotherhood and romantic relationships. Therefore, the verses were categorized as either Beijing-themed or non-Beijing-themed according to the lyrics’ content. For each performer, two verses were selected; these were extracted from the performer's most liked or played song on Netease Cloud Music in each of the two thematic categories. Some of the rappers belong to the same hip hop group and always perform together (i.e. three of the second generation rappers are in a group together, as are two of the third generation rappers). When they perform a song in a group, each artist creates and performs his own verses. For these artists, each one's own verses within the same song were coded separately. The length of the coded verses for each artist is approximately 67 to 110 seconds, with an average duration of 83.6 seconds. A total of fourteen songs, six from the second generation and eight from the third, are included in this study (the artists and songs are listed in the appendix).

Coding of the four linguistic variables

In order to investigate the phonological features in the selected songs, two kinds of coding were conducted. For the first three features, all coronal sibilants were perceptually coded by the author (a native speaker of Northern Chinese, a regional variety mutually intelligible with BM): (i) dental sibilants /s/, /ts/, /tsʰ/ for the interdental realization (N = 589); (ii) retroflex fricatives /tʂ/, /tʂʰ/, /ʂ/ for the lenited realization (N = 1144); and (iii) palatals /tɕ/, /tɕh/, /ɕ/ for the fronted realization (‘feminine accent’; N = 1222). Thus, the coding for each of these features is binary depending on its realization: (i) interdental or not; (ii) lenited or not; and (iii) fronted or not. Given that prior work has found that the fronted palatals occur more often when the following vowel is unrounded than rounded (Li Reference Li2017; Wang Reference Wang2022), the roundness of palatals’ following vowel was also coded to examine the linguistic-internal constraints of their fronted realization.

The fourth feature, rhotacization, is a subsyllabic suffix and its distribution is lexically conditioned. The twenty verses contain 293 instances of rhotacization; repeated occurrence in a song's refrain was only counted once. As prior work shows that rhotacization in Chinese rap music may enforce rhyming (Lin & Chan Reference Lin and Chan2021), whether the rhotacization played a role in a line-final rhyme was coded. Table 1 presents a summary of token counts for all four phonological features.

Table 1. Four linguistic features in Beijing-themed and non-Beijing-themed songs by two generations of Beijing rappers.

To maintain the consistency of the measures and increase the coding's reliability, I conducted the coding twice, in June 2021 and March 2022. The rate of internal consistency is over 90%. Inconsistencies were resolved through discussion with two graduate students (native speakers of Northern Mandarin) trained in sociophonetics.

Statistical modeling

The data were quantitively analyzed via generalized linear mixed-effects modeling, using the glmer function of the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017) in R (R Core Team 2018). While this study is interested in intergenerational differences, individuals may also have idiosyncrasies in the production of different words. Therefore, the models incorporated random effects of individual and word. The best fit models were selected via model comparison using ANOVA and based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Fixed effects of generation, theme, and their interaction were included in all models. The effects of linguistic feature and its interaction with generation were added into the overall model of the three binary BM features.

Results

This section first presents the overall findings regarding the three binary variables, followed by the findings for each one separately (i.e. dental sibilants interdentalized or not [interdentals]; retroflex fricatives lenited or not [lenition]; palatals fronted or not [fronted palatals]). It then presents the findings from the analysis of rhotacization.

Figure 2 presents the overall rates of the realization of lenited retroflexes, interdentalized dentals, and fronted palatals in the Beijing male rappers’ performance by generation and by thematic category. In no category is more than half of the total number of retroflexes, dentals, and palatals realized as the BM variant, but thematic category affects the rate of realization, particularly for the third generation.

Figure 2. Overall rates of the three BM features’ realization in the two thematic song categories by the two generations of rappers.

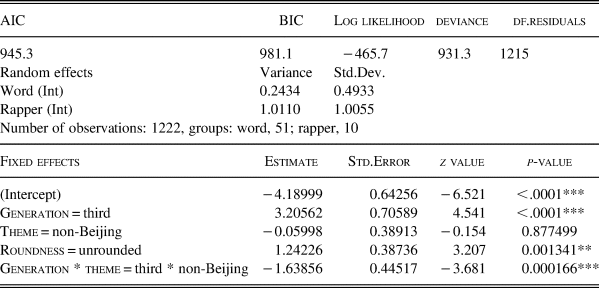

An overall model incorporating all three binary linguistic features to examine statistical differences among the effects shows no significant main effect of generation or theme (Table 2). Although lenited retroflexes and fronted palatals are significantly less likely to be realized than interdental sibilants, this result might be due to the larger sample sizes of the first two features. Therefore, I first focus on the interactions in the overall model, and then present three submodels, one for each of these linguistic features.

Table 2. Overall generalized linear mixed-effects model for lenition, interdental, and fronted palatal.

* indicates significance at p < .05; ** at p < .01; *** at p < .001.

The analysis of the interaction between generation and theme shows that the third generation is significantly less likely to produce BM features in non-Beijing-themed songs. Among the three binary features, they are significantly less likely to produce lenition but favor the use of fronted palatals.

Tables 3, 4, and 5 summarize the results of individual models run for lenition, the interdental, and the fronted palatal, respectively. For lenition, no significant difference was observed between generations or themes (Table 3). This result is unsurprising given the similarly low rates of lenition for both generations and both themes (Figure 2), although the second generation produced slightly more lenition than the third generation, and the third produced no lenition in non-Beijing-themed songs.

Table 3. Generalized linear mixed-effects model for lenition.

*** indicates significance at p < .001.

Table 4. Generalized linear mixed-effects model for the interdental.

* indicates significance at p < .05, ** at p < .01.

Although the overall model showed no significant difference related to the production of interdentals, the submodel shows a significant interaction between generation and theme (Table 4), indicating a distinction between the two themes in the third generation's performance: The third generation is significantly more likely to produce interdentals, a BM feature closely associated with the street-culture-related characterological figure of the ‘Alley Saunterer’ (Zhang Reference Zhang2018) in Beijing-themed songs.

Regarding the production of fronted palatals, the submodel shows a significant effect of generation and a significant interaction between generation and theme (Table 5). These results indicate that the third generation is significantly more likely than the second to use this feature, and significantly less likely to use it in non-Beijing-themed songs than in Beijing-themed songs. In terms of the roundness of the following vowel, consistent with the prior findings in other studies (Li Reference Li2017; Wang Reference Wang2022), the palatals (j, q, x) are realized as fronted significantly more often when preceding unrounded vowels than rounded ones.

Table 5. Generalized linear mixed-effects model for the fronted palatal.

**indicates significance at p < .01; *** at p < .001.

Unlike the three binary BM features, rhotacization is attached to a syllable at the final position, and whether a syllable can be rhotacized is determined lexically (Zhang Reference Zhang2018). The row on rhotacization in Table 1 shows its distribution in the selected verses. As the table indicates, both generations of rappers tend to use considerably more rhotacization in Beijing-themed songs. This pattern makes sense for two main reasons; first, rhotacization is prevalent in Beijing vernacular speech, and second, Beijing-themed songs contain many Beijing-culture-related expressions that involve rhotacization. The second generation's use of rhotacization is slightly greater than that of the third generation in both thematic categories. The following example from the song Beijing Hua ‘Beijing Mandarin’, performed by the group Zang Lir ‘Dirty truth’, offers a vivid illustration of rhotacization distribution in Beijing rap music.

(1) Lyrics extracted from the song Beijing Hua by the rap group Zang Lir

1 Ni yao wen wo Beijing de shenxian dou zhu nar

‘If you want to ask me where (nar) Beijing's immortal beings live’

2 Na bixu dou dei zhu zai hutongr limianr

‘They live in (limianr) the hutongs (hutongr ) for sure’

3 Siheyuanr

‘Quadrangle courtyard houses (siheyuanr)’

4 Bie kan gemenr qiong de zhi shengxia pugai juanr

‘Even though I (gemenr [i.e. local slang for oneself]) am so poor I have only a cotton mattress (pugai juanr [i.e. an idiom for having very few possessions])’

5 Dan wo haishi bu yuanyi feixin zuan na qian yanr

‘I still don't give a shit about money (qian yanr [i.e. an idiom about money implying the preference to earn it unscrupulously rather than working for it])’

6 Beijing de hunr

‘Beijing's soul (hunr)’

7 Haiyou Beijing de shair

‘And Beijing's color (shair, [i.e. the nature or impression of Beijing city])’

8 Beijing de fangyan

‘Beijing dialect’

9 Haiyou Beijing de fanr

‘And Beijing's style (fanr)’

This short verse shows that rhotacization frequently co-occurs with cultural terms indexing Beijing lifestyle, such as hutongr and siheyuanr, and plays an important role in forming rhyming word pairs (Lin & Chan Reference Lin and Chan2021), leading to considerably more rhotacization in the Beijing-themed songs. In contrast, the non-Beijing-themed songs, for example, Bu Genfeng ‘Don't follow the trend’, by the same group, only contains seven rhotacizations, including the one in their group name, Zang Lir, and two used as a rhyme.

Of the 293 observations of rhotacization, 117 are line-final, and over 60% (seventy) of them are used as the end rhyme to form the rhyming set in the verse. Table 6 presents the output of a mixed-effects model testing the use of rhotacization as the rhyme. Similar to the overall model of the other three features, this model shows no significant effect of generation or theme, but does indicate that the third generation is significantly less likely to use rhotacization as the rhyme in non-Beijing-themed songs.

Table 6. Generalized linear mixed-effects model for rhotacization as the rhyme.

* indicates significance at p < .05.

Both rhotacization of finals and rhotic lenition contribute to the ‘heavy r-sound’ of the Beijing accent and the construction of the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ persona (Zhang Reference Zhang2018); therefore, rhotacization and lenition should also be considered together when interpreting statistical results. As shown in the previous section, the second generation produces more rhotacization and more lenition than the third generation in their hip hop performance (Figure 2, Tables 2 and 6), which indicates their stronger preference for ‘heavy-r sounding’ BM. In addition, the third generation tends to reserve rhotacization as the rhyme for Beijing-themed rather than non-Beijing-themed songs.

In sum, this study's analysis shows that the use of the four BM features varies across the two generations, and it identifies significant differences in the interaction between generation and theme. The third generation shows a clearer distinction between Beijing-themed and non-Beijing-themed songs in terms of the use of all four BM features, and greater use of the fronted palatal, compared to the second generation.

Discussion

This analysis of four BM features (i.e. rhotacized syllable finals, lenited retroflexes, interdentalized dental sibilants, and fronted palatals) used in Beijing-flavor rap music among local male rappers has identified that although both generations use the same set of linguistic features, their performance exhibits generational and theme-based stylistic differences. The second generation keeps a rather low but similar rate of the use of each variable to maintain their Beijing identity across Beijing and non-Beijing themes. However, the third generation tends to draw a clearer distinction between these two thematic categories in the sense that they use the variables, particularly the fronted palatals, at higher rates in Beijing-themed songs. In this section, imbued social meanings of these four BM features in the hip hop artists’ stylistic configurations is further disentangled.

Interaction between existing characterological figures and rap music

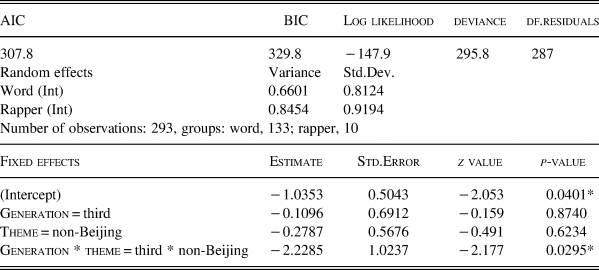

As an enregistered emblem of BM, rhotacization, together with lenition, is ideologically linked to the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ persona and substantially contributes to the ‘smooth’ quality of Beijing speech (Zhang Reference Zhang2005). When this iconic sign is incorporated into rap music by Beijing local rappers, it not only evokes localness, but also constitutes the rhythmic flow through rhematization (Gal Reference Gal2013). These links are confirmed by audiences’ perceptions of the ‘heavy-r sound’ in Beijing-flavor rap music, as exemplified by the comments from the Chinese social media platform Weibo in Figure 3. Although commenter A and B express opposing opinions about Beijing-flavor rap music, they both use expressions evoking the social quality of smoothness in relation to the use of rhotacization and lenition. Commenter A's negative comment uses the word youni (油腻), referring to oiliness or unctuousness, to describe the rappers, or more precisely their ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ personae. By contrast, commenter B's positive comment uses the word shun'er (顺耳, lit. ‘smoothen the ear’, meaning perceptually comfortable smoothness) to describe the sensory experience of Beijing-flavor rap music. As these two comments suggest, the rappers’ use of rhotacization and lenition is not only linked to the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ persona but also strengthens the smoothness of their rap's flow in perception. An iconic link of ‘smoothness’ is established between the ‘Beijing Smooth Rapper’ with his world-wise persona and the smooth sound of this place-linked musical subgenre (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000; Gal Reference Gal2013; D'Onofrio & Eckert Reference D'Onofrio and Eckert2021).

Figure 3. Audience comments on ‘heavy-r sound’ of Beijing-flavor rap music.

A similar strategy may explain the surprising use of ‘feminine accent’ in the third generation's performance. The iconic link between fronted palatals and the record scratch sound effect contributes to the aspect of musical expression, and the sharp and harsh quality of fronted palatals evokes a new social meaning related to masculinity and fierceness, further supporting the construction of the masculine and harsh rapper persona (Calder Reference Calder2019b; Wang Reference Wang2022).

Meanwhile, rhotacization and the interdental realization of the dental sibilants together also index a cohesive persona related to street culture in Beijing. Although the social types indexed by these two variables are slightly different, in that the ‘Smooth Operator’ could be from any social class and his characterological attributes center on street smarts and savoir-faire while the ‘Alley Saunterer’ is stereotypically linked with a lower class, uneducated image (Zhang Reference Zhang2018), when used in concert they construct a street-conscious style that aligns with the ideology that rap should come ‘from the streets and tell tales of street life’ (Alim Reference Alim, Sinfree Makoni, Ball and Spears2003:50). Both generations utilize these two variables to embody authentic Beijing roots and inherent street wisdom resulting from the hutong culture.

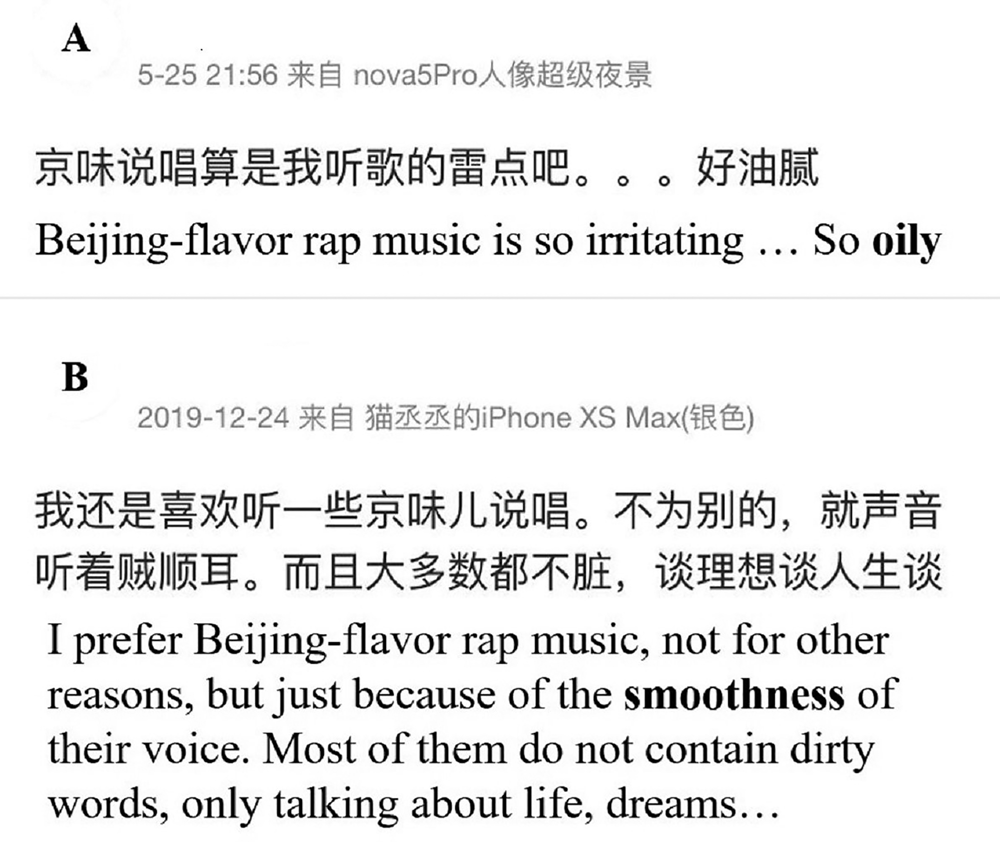

Figure 4 is an extract from an interview with Huizi, a third-generation rapper. When he introduces the hutong he grew up in, he uses Tongrooklyn to name it, suggesting a correspondence between Beijing's hutongs and Brooklyn in their status in hip hop culture. Huizi goes on to claim, “this is the real Ghetto”, authenticating himself as an in-group member of the hip hop nation. Within the hip hop context, this new constructed persona shares some common characteristics with another stereotypical figure, the hip hop hustler, who comes from a poor, urban ‘hood’, often with negative connotations of dishonesty and profiteering (Naumoff Reference Naumoff2014). This cultural alignment enables Chinese male rappers to authentically identify with general hip hop culture and to carefully maintain their street credibility by signaling their local street-conscious identity.

Figure 4. Huizi introducing the hutong he grew up in.

The construction of Beijing male rapper personae through multiple indexical paths

Based on the above discussions regarding the BM variables examined in this study, I further propose a view of indexical fields to demonstrate how they are related to the respective constructed personae through multiple indexical paths. In Figure 5, the upper part includes the four linguistic variables with their indexed social meanings and associated characterological figures in the local context of Beijing. The lower part of the figure presents iconic relationships between the linguistic variables of rhotacization and fronted palatals and hip hop's musical characteristics. For the fronted palatal, traditionally known as ‘feminine accent’ in BM linguistics, the figure indicates the coexistence of seemingly contradictory meanings (i.e. soft, delicate femininity vs. tough, harsh masculinity). As indexicality is dependent on linguistic style, in this case, in the construction of the Chinese male rappers’ style, the femininity-related social meanings are excluded from the rappers’ style construction (the gray area). It should be noted that this shift does not happen randomly but is achieved through the feature's co-occurrence with other semiotic resources; the iconic uses of rhotacization to evoke a smooth rapping flow and of fronted palatals to evoke the sharp record scratch sound effect emerge only in conditions that foreground hip hop ideologies, particularly in the local Beijing hip hop scene and in local Beijing male rappers’ performance (Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000; Wang Reference Wang2022).

Figure 5. Indexical field for each analyzed BM feature and associated personae (boxes = social meanings, bold = social types, italic = iconic construal of indexes in the hip hop context, gray area = co-occurring variables constituting Beijing male rappers’ styles).

The figure also demonstrates how these variables function at different orders of indexicality (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003), moving from demographic categories, such as region, age, and gender, to iconic associations of sound situated in rap music (Feld et al. Reference Feld, Fox, Porcello, Samuels and Duranti2004; Coupland Reference Coupland2011). The higher-order indexicality is associated with the situationally grounded persona—the skilled male rapper image in the new stylistic ensemble. In other words, features that began as indexes indicating people's place-related identity (i.e. rhotacization, lenition, interdentals, and fronted palatals indexing Beijing origin) take on connections with gender and class and/or are reconstrued as iconic of the genre of rap music (i.e. rhotacization points to the smooth rap flow; fronted palatals to the record scratch sound effect). Being grounded in hip hop-related ideologies, the use of BM variables in rap music continues to reinforce existing form-meaning links while also highlighting the musical performance as aesthetic expression via phonetic iconicity, giving rise to higher-order social meanings.

Changing personae among two generations

When we look at the rappers’ use of linguistic features and their songs’ themes, while both generations of rappers focus on local street style via characterological figures, the third generation seems to draw a clearer distinction between Beijing-themed and non-Beijing-themed songs. One possible explanation for this shift in style between the second and third generation is that the two generations face different social environments and hence require different strategies to construct hip hop authenticity. As mentioned in the introduction, during the underground era of Chinese rap music, some songs from the second generation were blacklisted due to vulgar language style, active social commentary, and rebellious attitudes, regardless of the songs’ themes. In 2017, rap entered mainstream media in China, and became subject to strict censorship. Hence, the third generation is more aware of the lines they cannot cross if they want to be public performers, and they therefore seek new ways to establish their hip hop authenticity. Although some veteran rappers have criticized the third generation as inauthentic and too commercial, there is no doubt that current hip hop culture is in fact commercialized and has a wide mainstream audience in the Chinese mainland (Sullivan & Zhao Reference Sullivan and Zhao2019; Luo & Ming Reference Luo and Ming2020). Beyond the impact of this shift toward the mainstream, however, the difference between the second and third generations may also reflect genuinely different ideological beliefs regarding what constitutes real hip hop. The result is a shift from the second generation's social concerns, politically oriented lyrics, and ‘gang’-style, to the third generation's strategic emphasis on rap techniques and being true to their Beijing roots while still maintaining the street credibility established by the second generation during hip hop's underground years.

Last but not least, other subgenres of Chinese rap music, such as Sichuanese trap, have been emerging over the past two decades, often featuring regional dialects and new techniques, and threatening the status of Beijing rap music in Chinese hip hop (Amar Reference Amar2018). However, during the underground era, there were no other comparable subgenres; hence, the second generation of Beijing rappers did not need to call excessive attention to their place-related identity. Given the phonological similarity of Mandarin Chinese and Beijing Mandarin, the third generation of Beijing rappers may have a greater tendency to explore distinctive linguistic features beyond rhotacization that can represent Beijing rap music, highlighting their determination to keep Beijing rap vital. This impulse might explain the innovative use of the characteristic feature of ‘feminine accent’, fronted palatals, to construct a masculine and harsh male rapper persona that concurrently links with the musical characteristics of the hip hop genre by evoking the record scratch sound (Wang Reference Wang2022). Additionally, the less frequent use of lenited retroflexes in non-Beijing-themed songs among the third generation may indicate that they do not want to be heard as mumbling, and thus perceived as less skilled at fast-paced rapping compared to skilled rappers from other emerging subgenres. The third-generation singers display their agency in choosing their sound as they strive to construct a skilled rapper persona to confront the skillful new techniques and rhyme schemes of rap artists in other subgenres. In the changing landscape of Chinese rap music, Beijing male rappers are altering their personae, shifting from social critics to nostalgic but skilled Beijing rappers who are proud of old-school Chinese rap music and the local culture.

In summary, the findings of this study reveal that co-occurring BM features of rhotacization, lenition of retroflexes, interdentalized dental sibilants, and fronted palatals contribute to the construction of a street-smart, tough, and masculine rapper identity, and further, that they are being iconized as indexes of rap music, both musically and ideologically, in the context of Beijing's hip hop community. Hence, the study provides further evidence that the process of naturalizing the form-meaning link between linguistic variables and rap music is not always direct, and it does not always focus on the use of AAE or certain marginalized urban vernaculars. Rather, it is mediated through ideologies or elements associated with hip hop, such as street-wisdom, masculinity, and ‘ghetto’ neighborhoods. Although previous studies on the enregisterment of ‘ghetto’ or ‘street’ language outside of the African American community have illustrated the existing stereotypical indexical links between the speech styles of ethnic minorities and rap music (Androutsopoulos & Scholz Reference Androutsopoulos and Scholz2003; Stæhr & Madsen Reference Stæhr and Madsen2017), the current study, building on a recent research trend in third-wave variationist sociolinguistics, further highlights that the bricolage of BM features in rap music performance reflects a process in which assemblages of semiotic resources cohere ideologically to construct recognizable personae, which are closely connected to both cultural and musical expressions rooted in the genre. In other words, the linguistic construction of cohesive hip hop personae by Beijing male rappers is based on cultural concepts in the local context associated with hip hop authenticity and the performers’ understanding of sophisticated rap skills, not a simple overlaying of local linguistic elements.

Conclusions

Rooted in theories of indexicality, this study was motivated by the question of what styles are indexed by four BM features, which are ideologically linked to local social types, in Beijing male rappers’ performance. Through the investigation of the social meanings each variable contributes to the construction of cohesive personae, the study found that the two existing local social types, the ‘Beijing Smooth Operator’ and the ‘Alley Saunterer’, engage well with the hip hop context by virtue of attributes shared with rappers’ stereotypical image, such as lack of education, fecklessness, and street-wisdom (Zhang Reference Zhang2018). While rhotacization, lenition, and interdentalization in the original cultural schemata of Beijing are not considered ‘ghetto language’ or ‘street talk’, which is closely connected with marginalized groups and nonstandardness (cf. Stæhr & Madsen Reference Stæhr and Madsen2017), their indexed social meanings are associated with street credibility and urban street lifestyle resulting from Beijing's social culture. In addition, Beijing local rappers also employ the ‘mellow and smooth’ quality of rhotacization to improve the smoothness of their rap flow, and the sharpness of fronted palatals to evoke the record scratch sound effect in their performance (Zhang Reference Zhang2008; Wang Reference Wang2022). In this sense, the innovative utilization of these two variables corresponds to the musical characteristics of the hip hop genre and reflects Beijing local rappers’ particular attention to rapping techniques, further constructing a skilled rapper persona.

This research suggests that, responding to both ‘hip hop fever’ and the ‘hip hop bans’, two generations of Chinese rappers display distinct ideological positions by employing similar combinations of co-occurring variables to index different thematic styles. This study does not, for lack of space, address all linguistic constraints on variation in the production of these BM variables, but it found that Beijing-based rappers retain internal constraints in their performance in terms of fronted palatals’ production. To develop a full picture of BM features in rap music, more language-internal constraints should be taken into consideration in further investigations. In a more theoretical direction, the results of the current study support a move toward analyzing stylistic packages, which configure an indexical field through different paths, to better understand the indexical field's complexity.

Appendix: Hip hop artists and songs