Article contents

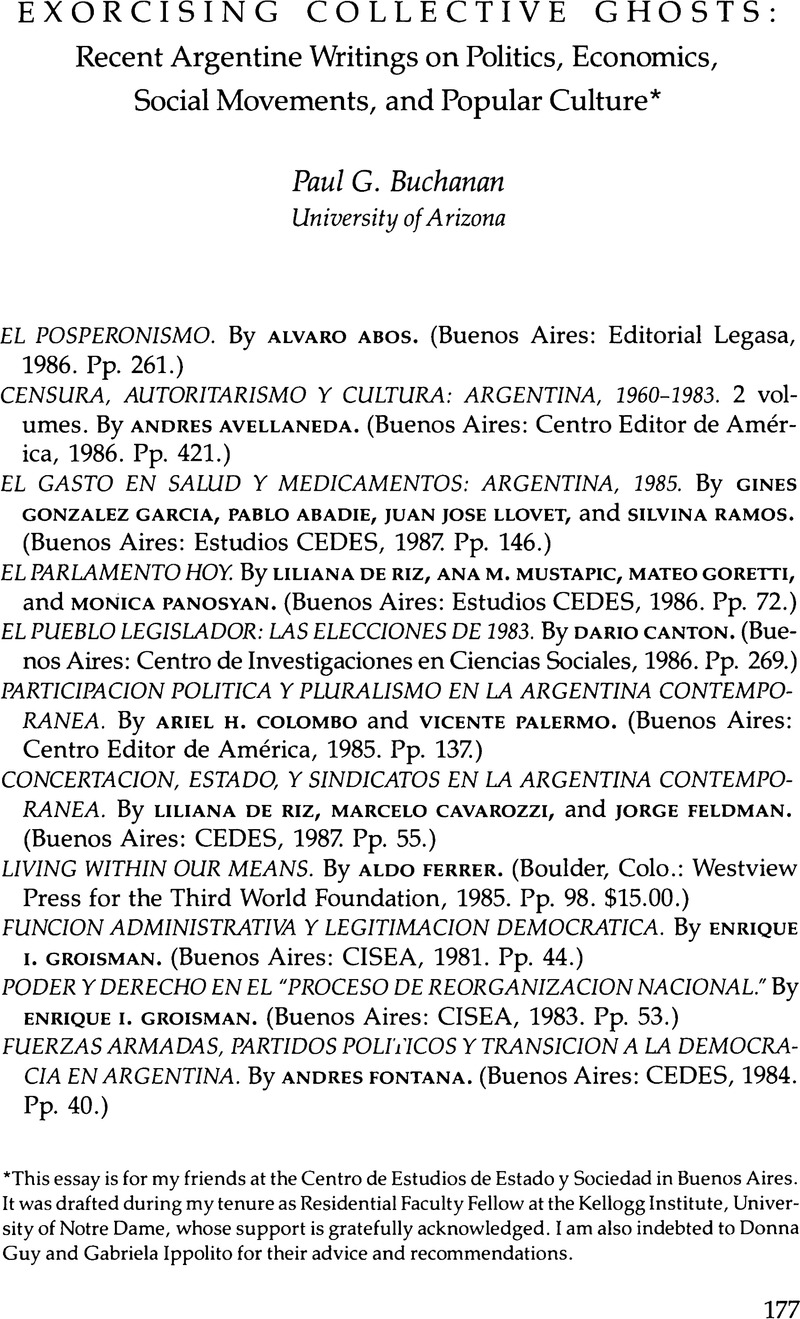

Exorcising Collective Ghosts: Recent Argentine Writings on Politics, Economics, Social Movements, and Popular Culture

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1990 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

This essay is for my friends at the Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad in Buenos Aires. It was drafted during my tenure as Residential Faculty Fellow at the Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame, whose support is gratefully acknowledged. I am also indebted to Donna Guy and Gabriela Ippolito for their advice and recommendations.

References

Notes

1. CONADEP, Nunca más (Buenos Aires: EUDEBA, 1984).

2. On the terms organic crisis, dominance, and hegemony, see Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks, edited and translated by G. Norwell Smith (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 210–60. The term empate hegemónico (hegemonic stalemate) is attributed to Juan Carlos Portantiero. For an application of these concepts to the Proceso, see Paul G. Buchanan, “The Varied Faces of Domination: State Terror, Economic Policy, and Social Rupture during the Argentine ‘Proceso,‘” American Journal of Political Science 31, no. 2 (1987):336-82. The term impossible game comes from Guillermo O'Donnell, Modernization and Bureaucratic Authoritarianism: Studies in South American Politics (Berkeley: Institute of International Studies, University of California, 1973).

3. This perspective has been especially well applied to the instances of peaceful regime transition from authoritarian to democratic capitalism in Southern Europe and Latin America. See, for example, Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Prospects for Democracy, edited by Guillermo O'Donnell, Philippe C. Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead, 4 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986).

4. The best analyses of postauthoritarian Argentina using this type of approach are found in José Nun and Juan Carlos Portantiero, Ensayos sobre la transición en la Argentina (Buenos Aires: Puntosur Editores, 1987). Because of the length and substance of this work, it merits a separate review from that undertaken here.

5. I am indebted to Roberto Da Matta for explaining to me the relational aspects of rationality and the notion of ethical dualism, although this particular interpretation is my own.

6. Adolfo Canitrot, La disciplina como objectivo de la política económica: un ensayo sobre el programa del gobierno argentino desde 1976, Estudios CEDES, no. 12 (1980).

7. On this point, see Paul G. Buchanan and Robert Looney, Relative Militarization and Its Impact on Public Policy: Budgetary Shifts in Argentina, 1963-1982, Western Hemisphere Area Studies Technical Report no. 7 (NPS 56–88–002), Department of National Security Affairs, Naval Postgraduate School, July 1988.

8. On the evolution of organized labor over the last half-century, see Alvaro Abós, La columna vertebral: sindicatos y peronismo (Buenos Aires: Hispanoamérica, 1986); Abós, Las organizaciones sindicales y el poder militar (Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América, 1984); Marcelo Cavarozzi, Sindicatos y política en Argentina (Buenos Aires: CEDES, 1984); Torquato Di Tella, Política y clase obrera (Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América, 1983); Rubén Rotundaro, Realidad y cambio en el sindicalismo (Buenos Aires: Editorial Pleamar, 1971); Juan Carlos Torre, Los sindicatos en el gobierno, 1973-1976 (Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América, 1983); and Rubén Horacio Zorrilla, Estructura y dinámica del sindicalismo argentino (Buenos Aires: La Pléyade, 1974). For an interesting account in English, see David James, Resistance and Integration: Peronism and the Argentine Working Class, 1946-1976 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

9. For the argument that the Proceso, whatever its hegemonic pretensions, was no more than an exercise in domination (albeit a sophisticated one), see Buchanan, “The Varied Faces of Domination.”

10. Also available as Kellogg Institute Working Paper no. 2, 1983.

11. See, for example, Alain Rouquié, “Demilitarization and the Institutionalization of Military-Dominated Polities in Latin America,” in O'Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead, Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Prospects for Democracy, Vol 3: Comparative Perspectives; and Alfred Stepan, Rethinking Military Politics (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988). The term partial regime is taken from Philippe C. Schmitter, “The Consolidation of Political Democracy in Southern Europe,” manuscript.

12. The best work in English on the cultural dimension of Argentine democratization is The Redemocratization of Argentine Culture, 1983 and Beyond: An International Research Symposium, edited by David William Foster (Tempe: Center for Latin American Studies, Arizona State University, 1989). I am indebted to Edward Williams for calling my attention to this work.

13. For an excellent survey of the multiple facets of democratic cultural promotion, see Debates 2, no. 3 (Apr.-May 1985), which is devoted to this theme. This journal is published by CEDES in Buenos Aires. The issue contains articles by a broad array of authors, including several cited here.

14. Guillermo O'Donnell, “Estado y alianzas en la Argentina, 1955–1970,” Estudios CEDES/G. E. CLACSO, no. 5 (Oct. 1976).

15. Barry Ames, Political Survival: Politicians and Public Policy in Latin America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989), 35–40.

16. Norberto Bobbio, El futuro de la democracia (Barcelona: Plaza y Janés, 1986), quoted in Abós, El posperonismo, 139.

17. O'Donnell's views are well expounded in Transitions from Authoritarian Rule. On bottom-up processes of regime transition and democratic consolidation, see Paul G. Buchanan, “Democratization Top-Down and Bottom-Up,” in Authoritarian Regimes in Transition, edited by Hans Binnendijk (Washington, D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, 1987).

18. Adam Przeworski and Michael Wallerstein, “The Structure of Class Conflict in Democratic Capitalist Societies,” American Political Science Review 76, no. 2 (June 1982): 215–38; Przeworski, “Material Bases of Consent: Economics and Politics in a Hegemonic System,” Political Power and Social Theory 7 (1980):21-66; Przeworski, “Compromiso de clases y estado: Europa Occidental y América Latina,” in Estado y política en América Latina, edited by Norberto Lechner (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1985); and Przeworski, “Democracy as a Contingent Outcome of Conflicts,” in Constitutionalism and Democracy, edited by Jon Elster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

19. For an extended discussion of concertation as an instrument of democratic consolidation, see Paul G. Buchanan, “State, Labor, Capital: Institutionalizing Democratic Class Compromise in the Southern Cone,” manuscript, chap. 3.

20. For discussion of concertation in the Southern Cone, see among many others Novos Estudos CEBRAP, no. 13 (Oct. 1985):2-44, a special section on social pacts, with emphasis on Brazil; Norberto Lechner, Pacto social en los procesos de democratización: la experiencia latinoamericana (Santiago: FLACSO, 1985); Carlos Pareja, “Las instancias de concertación: sus presupuestos, sus modalidades y su articulación con las formas clásicas de democracia representativa,” Cuadernos del CLAEH no. 32 (1984/4):39-41; Guillermo O'Donnell, “Pactos políticos y pactos económicos sociales: por que sí y por que no,” CEDES-CEBRAP mimeo, Buenos Aires, 1985; Angel Flisfisch, “Reflexiones algo obliquas sobre el tema de la concerfación,” Desarrollo Económico 26, no. 101 (Apr.-June 1986):3-19; and PREALC, Política económica y actores sociales: la concertación de ingresos y empleo (Santiago: Organización Internacional de Trabajo, 1988).

21. This work was also published in Crítica y Utopia 9 (1982): 127–47.

22. For two contrasting examples of state-corporatist approaches, see Paul G. Buchanan, “State Corporatism in Argentina: Labor Administration under Perón and Onganía,” LAR 20, no. 1 (1985):61-95.

23. For a good analysis of the 1973–74 attempt, see Robert Ayres, “The ‘Social Pact’ as Anti-Inflationary Policy: The Argentine Experience since 1973,” World Politics 28, no. 4 (July 1976):473-501.

- 4

- Cited by