Article contents

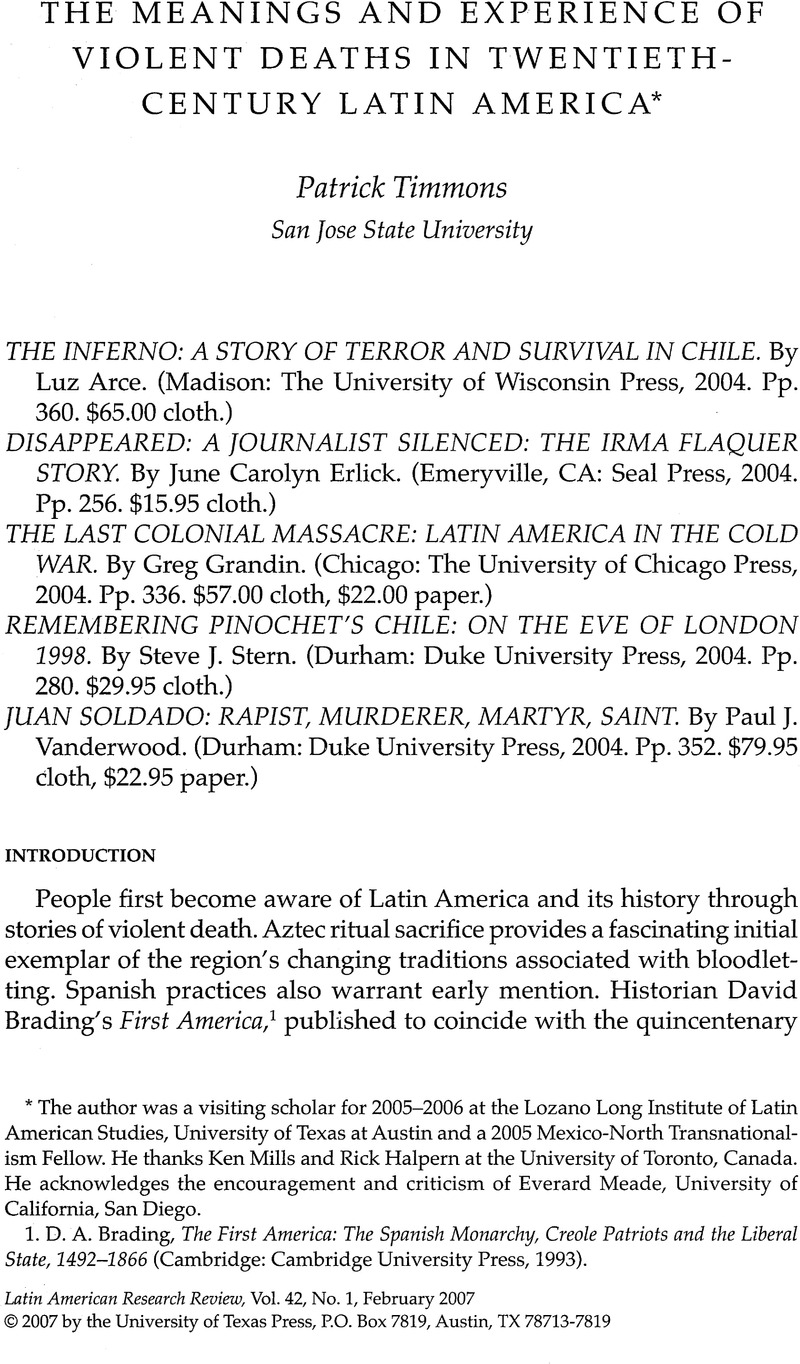

The Meanings and Experience of Violent Deaths in Twentieth-Century Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2007 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

The author was a visiting scholar for 2005-2006 at the Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas at Austin and a 2005 Mexico-North Transnationalism Fellow. He thanks Ken Mills and Rick Halpern at the University of Toronto, Canada. He acknowledges the encouragement and criticism of Everard Meade, University of California, San Diego.

References

1. D. A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots and the Liberal State, 1492-1866 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

2. Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability (New York: New Press, 2003), xi.

3. Tina Rosenberg, Children of Cain: Violence and the Violent in Latin America (New York: W. Morrow, 1991), 187.

4. See Table 4.1 in Alberto Concha-Eastman, “Urban Violence in Latin American and the Caribbean: Dimensions, Explanations, Actions,” and chapter 4 in Susan Rotker, ed., Citizens of Fear: Urban Violence in Latin America with Katherine Goldman (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 42.

5. The phrase appears in David Garland, Punishment and Modern Society: A Study in Social Theory (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1990).

6. The name is erroneous because the law of flight is a practice, usually of extrajudicial execution, not a law per se.

7. The “crime and punishment” approach may be found in: Ricardo D. Salvatore, Carlos Aguirre, and Gilbert M. Joseph, eds., Crime and Punishment in Latin America: Law and Society since Late Colonial Times (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Carlos A. Aguirre and Robert M. Buffington eds., Reconstructing Criminality in Latin America (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 2000); Gabriel Haslip-Viera, Crime and Punishment in Late Colonial Mexico City, 1692-1810 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999); Elisa Speckman Guerra, Crimen y castigo: Legislación penal, interpretaciones de la criminalidad y administración de justicia, Ciudad de México, 1872-1910 (México: El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Históricos: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 2002).

8. Stern’s approach may be usefully contrasted against those of Ariel Dorfman, Exorcising Terror: The Incredible Unending Trial of General Augusto Pinochet (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002) and Julio Scherer García, El perdón imposible: No solo Pinochet (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2005).

9. One classic is Jacobo Timmerman, Prisoner Without a Name, Cell Without a Number, translated by Timothy Talbot (New York: Vintage Books, 1981). For a different perspective of Dirty War violence in Argentina see Andrew Graham-Yool, A State of Fear: Memories of Argentina’s Nightmare (London: Hippocrene Books, 1986).

10. June Carolyn Erlick, Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced: The Irma Flaquer Story foreword by Stephen Kinzer (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2004, 315).

11. Erlick reproduces the Time photograph in her biography.

12. A collection of Flaquer’s articles may be found in Irma Flaquer, selección de textos Mirena Martínez, La que nunca calló: Artículos periodísticos (Guatemala: COPREDEH, 2002). Her letter to the assassin who planted a bomb in her car may be found in Irma Flaquer, A las 12:15 el sol (Guatemala: Editorial El Sol, 1970).

13. Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico, Guatemala, Memory of Silence (Guatemala: CEH, 1988).

14. Samantha Power, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 2002). Conversations with Everard Meade have shaped my orientation towards Power. Telephone conversation, Meade and Timmons on 16 November 2005.

- 1

- Cited by