Article contents

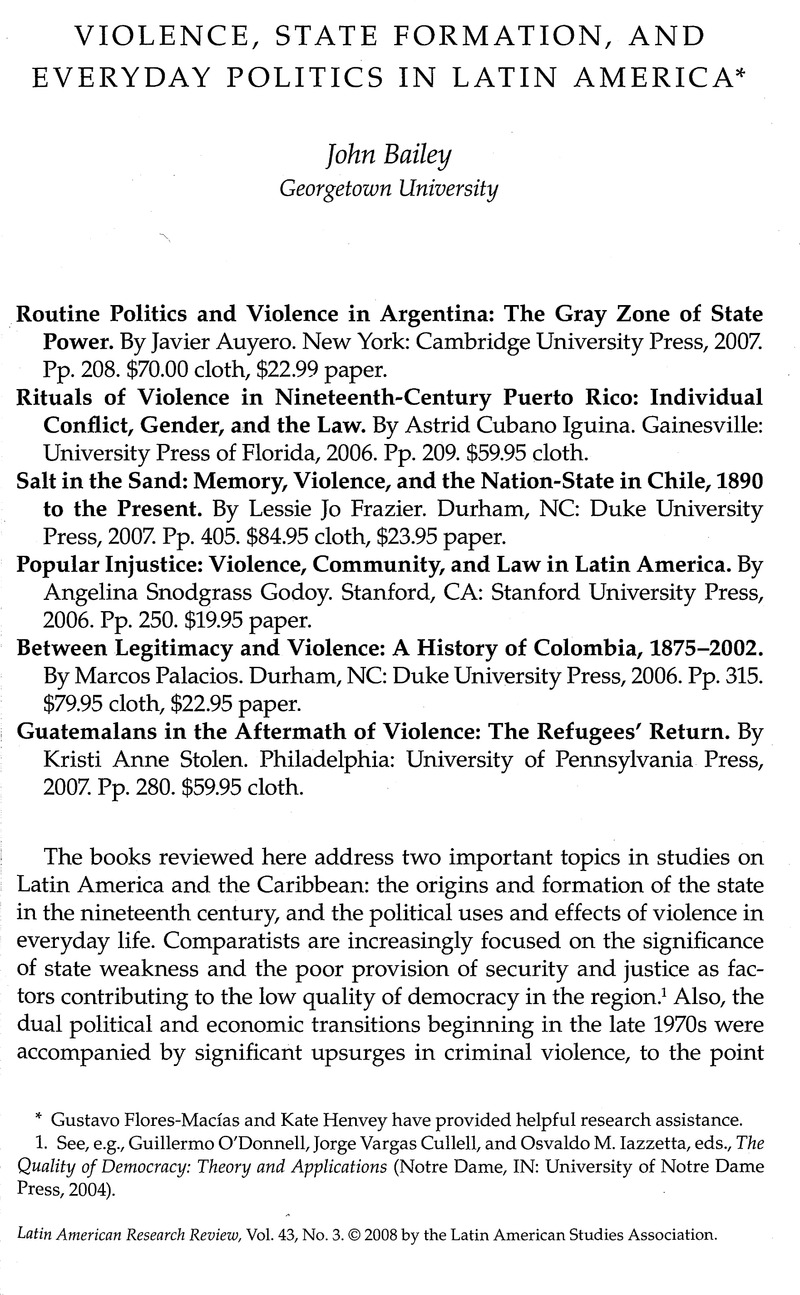

Violence, State Formation, and Everyday Politics in Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2008 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

Gustavo Flores-Macías and Kate Henvey have provided helpful research assistance.

References

1. See, e.g., Guillermo O'Donnell, Jorge Vargas Cullell, and Osvaldo M. Iazzetta, eds., The Quality of Democracy: Theory and Applications (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004).

2. Respondents citing delincuencia as their country's most serious problem rose from 6 percent in 1995 to 17 percent in 2007, to tie with unemployment. Of the countries reviewed here, Guatemala, Chile, and Argentina (at 38 percent, 30 percent, and 25 percent, respectively) scored well over the average, while Colombia is a surprisingly low 6 percent (Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe Latinobarómetro: Bancos de datos en línea, Noviembre 2007 (http://www.latinobarometro.org).

3. Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Paul Pierson, Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

4. Fernando López-Alves, who focuses his analysis of state formation in the 1810s-1880s, is an exception. See his State Formation and Democracy in Latin America, 1810–1900 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000).

5. Charles Tilly, “Reflections on the History of European State-Making,” in Charles Tilly, ed., The Formation of National States in Western Europe, 3–84 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975).

6. Miguel Ángel Centeno, Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America, 14–15 (University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2002).

7. Ibid., 23, 29; original emphasis.

8. The nation-building effects of early struggles by the government against bandits and indigenous groups on Chile's southern frontier in the 1820–1830s are explored by Pilar M. Herr, “Indians, Bandits and the State: Chile's Path toward National Identity, 1819–1833” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 2001). For a useful discussion of Andrés Bello and the origins of code law in Chile in the 1850s, see Iván Jaksic, Andrés Bello: Scholarship and Nation-Building in Nineteenth-Century Latin America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

9. To pursue these contrasts the interested reader might begin with Timothy Mitchell, “The Limits of the State: Beyond Statist Approaches and their Critics,” American Political Science Review 85, no. 1 (1991): 77–96; and Joel S. Migdal, State in Society: Studying How States and Societies Transform and Constitute One Another (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). Centeno reflects on Foucauldian theory and the state in the Latin American context in “The Disciplinary Society in Latin America,” in Miguel Ángel Centeno and Fernando López-Alves, eds., The Other Mirror: Grand Theory through the Lens of Latin America, 289–308 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

10. In Argentina, the human costs of the military regime of 1976–1983 are estimated at more than fifteen thousand disappeared, though the precise number is disputed. In Guatemala, some two hundred thousand were killed from 1960 to 1996, the vast majority at the hands of the army (Human Rights Watch, Reluctant Partner: The Argentine Government's Failure to Back Trials of Human Rights Violators, December 2001, Section I [accessed January 29, 2008, at http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/argentina/argenl201–01.htm]; Human Rights Watch, World Report 2007: Events of 2006 [accessed January 29, 2008, at http://www.hrw.org/wr2k7/wr2007master.pdf]). If we use homicide rates as a proxy for overall crime, Argentina's ranged between four and six per one hundred thousand in the 1990s; the comparable figure for Guatemala ranges between seventeen and twenty-eight. If we include intentional deaths from causes other than homicide, the numbers for Guatemala in the 1990s range between forty-seven and sixty-two per one hundred thousand. Interested readers can explore the World Health Organization mortality data (accessed January 29, 2008, at http://www.who.int/healthinfo/morttables/en/).

11. On Argentina and Brazil, see, e.g., Mercedes S. Hinton, The State on the Streets: Police and Politics in Argentina and Brazil (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2006); on Mexico, see Diane E. Davis, “Undermining the Rule of Law: Democratization and the Dark Side of Police Reform in Mexico,” Latin American Politics and Society 48, no 1. (2006): 55–86.

12. On brown areas, see Guillermo O'Donnell, “The State, Democratization, and Some Conceptual Problems (A Latin American View with Glances at Some Post-Communist Countries),” in William C. Smith, Carlos H. Acuna, and Eduardo A. Gamarra, eds., Latin American Political Economy in the Age of Neoliberal Reform, 157–180 (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1994).

13. Godoy defines lynching as “incidents of physical violence committed by large numbers of private citizens against one or more individuals accused of having committed a ‘criminal’ offense, whether or not this violence resulted in the death of the victim(s)” (184).

14. Migdal, State in Society, 49.

- 3

- Cited by