Oaxaca, an overwhelmingly Indigenous and multi-ethnic region, shares with the rest of Mexico—and indeed many parts of the world—a history of agrarian conflict in which law and violence have existed in constant tension. But unlike other areas of Mexico where Spanish settlers dispossessed many Indigenous communities, most of Oaxaca's Native municipalities held onto their lands throughout the colonial period and beyond.Footnote 1 At the same time, the density and high number of Indian towns in Oaxaca exacerbated cycles of inter-Indigenous land disputes and criminal complaints regarding violent clashes in boundary lands between communities. This phenomenon is not a relic of the past; Native conflict over land persisted into the national period, and today's newspapers recount violent land invasions and territorial conflicts that are often deadly.Footnote 2

This article analyzes how Spanish law intersected with longue-durée Indigenous histories to produce performative judicial violence in disputes over boundary lands in colonial Oaxaca during a period when population growth and expansion and commercialization of the livestock industry put pressure on Indigenous lands.Footnote 3 In contrast with Indigenous town halls where according to Spanish law, Native justice was supposed to take place, boundary lands between Indigenous communities, marked by wooden crosses or piles of stones, were extrajudicial spaces where Native officials and villagers haggled over territory and authority (Figure 1). Porous by design, boundary lands were accessible to residents on either side for the collection of wood, medicinal plants, and other necessities. As the Indigenous population recovered during the late seventeenth century from a century and a half of decline due to epidemic disease—and then grew during the early eighteenth century—boundary lands became zones of contestation between Indigenous farmers and municipal officials looking to expand cultivation and pastureland. Native judicial officers used their coercive power and symbols of judicial authority to physically enter boundary lands and shape the course of legal disputes that were being heard in Spanish courts or had already been ruled upon by Spanish judges.

Figure 1. Boundary markers, Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, 2000. The date May 01, 1589 is painted onto the bottom of the gray cross in front and to the right, possibly referencing the day the territories of the communities were titled and the boundaries between the two communities were marked. Photograph by the author.

By combining Spanish legal procedures with extralegal ones, Native officials developed customary judicial practices and performances proper to their own jurisdiction in which objects invested with political, sacred, and quotidian meaning figured centrally. Staffs of office and whips wielded by Native authorities as emblems of Indian administrative and legal jurisdiction represented one category of the everyday materials of law. Clothing, farming implements, and livestock afforded other tools with which Indigenous farmers and authorities made legal claims. When reading land disputes alongside criminal cases of land invasions across Oaxaca's judicial archives, it becomes clear that Native officials and farmers used these objects to struggle over territory and authority in patterned cycles of litigation, land titling or contracts of joint-possession, and violence that often played out over decades or centuries and formed an enduring facet of agrarian custom in the region.

Ethnic Territory, Indian Jurisdiction, and Legal Possession

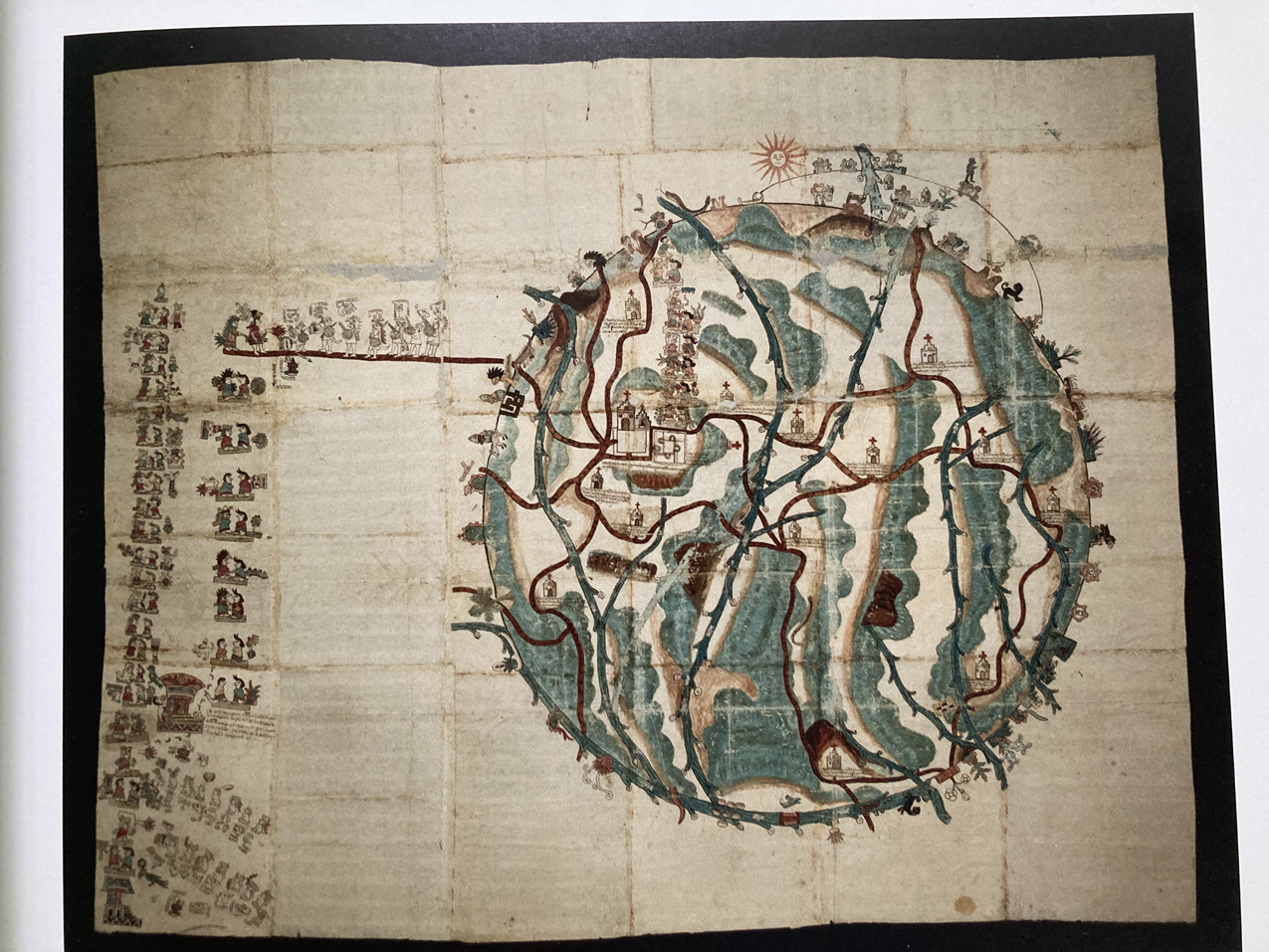

Colonial Indigenous legal practice rested on the interplay of pre-Hispanic Indigenous and Spanish institutions. The Indigenous ethnic state took distinct forms in different regions of Mexico, and even within the ethnically diverse region of Oaxaca. Despite the variation, some generalizations can be made. In Oaxaca, pre-Hispanic Indigenous authority derived from descent from royal lineages, and ethnic states were formed through marriage alliances. Features of the landscape, many of which were considered sacred, marked their porous territorial boundaries (Figure 2).Footnote 4 Commoners had direct access to land via usufruct, determined by ruling lords. The relationship between ethnic states and their subject communities was hierarchical, yet at the same time, conceived of in terms of autonomous, constituent parts that together formed a whole. The intersection of vertical and cellular relationships created fluidity; larger polities incorporated smaller communities through warfare or marriage, and those same communities could secede from larger entities through new alliances. The transition from fluidity to greater fixity in Indigenous socio-political organization represents one of the fundamental changes wrought by the Spanish conquest.Footnote 5

Figure 2. Teozacoalco map, Relaciones Geográficas de Antequera. Courtesy of the Benson Latin American Collection, Teresa Lozano Long Institute for Latin American Studies (LLILAS) Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, The University of Texas at Austin. This Mesoamerican-style map provides an idealized image of the community of Teozacoalco (a circle as emblematic of perfection), and represents its boundaries with place glyphs around the edges. See Barbara E. Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geofrácias (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 112–17.

The Spanish regime of property marked the most important post-conquest change in the relationship between Indigenous political authority and territory. The Spanish viewed the Indigenous elite as a seigneurial class along the lines of a European feudal nobility. Spanish law recognized the territory under the jurisdiction of Native lords as being titled estates based on the Spanish model of mayorazgo. Cacicazgos, as the estates of Native lords (caciques) came to be known, were bounded and fixed territories. Along with the land of the cacicazgo came customary rights owed to the nobility by commoners, such as personal service, tribute, and labor.Footnote 6

Spanish modes of land tenure and socio-political organization affected Native communities differently than they did the Native elite. Through the Church-sponsored program of congregación, the population that survived the devastating epidemics of the sixteenth century was concentrated into Spanish-style municipalities, which were in turn organized into a hierarchical relationship in which larger settlements known as cabeceras (head towns, or parish seats) exercised jurisdiction over smaller ones (sujetos). The governing bodies (cabildos) of these newly formed republics of Indians regulated access to designated communal lands via usufruct. Some communal lands were set aside for the support of the parish church. Forested boundary lands between communities, known as tierras baldías, supplied local residents with resources such as wood and grazing land, but could not be cultivated.Footnote 7 In addition to allocating communal lands, colonial Indigenous officials collected tribute, organized communal labor, and exercised jurisdiction over minor crimes and legal disputes within the community. This sphere of Indigenous colonial authority and the territorial base of the Indian community formed the foundation of Indian jurisdiction.Footnote 8

As the Indigenous population contracted and then recovered and expanded over the course of the colonial period, Indigenous municipalities fragmented. Demographic, ecological, and commercial pressures pitted Native communities against one another, and Indigenous commoners against their caciques in struggles over land that found expression in legal disputes and violence. Subject communities sought autonomy from cabeceras so that they could establish their own parish church and political and territorial jurisdiction.Footnote 9 The Spanish legal principle of possession, a “legal category that aimed to contain the vagaries of landholding in a colonial society that had fostered a kind of rolling chaos in property relations” exacerbated these agrarian conflicts, rather than ameliorating them.Footnote 10 The Siete Partidas defined possession as entering, occupying, and holding a piece of land, a concept that was distinct from ownership, which required legal title.Footnote 11 During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most Indigenous individuals and communities possessed land rather than owning it, since securing or producing title of ownership was more difficult than claiming possession in Spanish courts.

Claiming possession of land required physical manifestation of occupancy and use, including crops, dwellings, or structures of human settlement. When territory was disputed, such a requirement invited violence; people could be forcibly removed, and simple structures could be hastily erected or destroyed. Violence engendered by possession extended well beyond the contexts of Oaxaca and New Spain. In her study of territorial conflict between municipalities and settlements across Spanish and Portuguese frontiers in both early modern Iberia and South America, Tamar Herzog argues that violence was in fact an expression of the legal principle of possession: “Aggression…was also mandated by a legal logic that suggested that silence implied consent and reaction implied opposition.”Footnote 12 Violence as a means of claiming legal possession was therefore not irrational or atavistic, but rather “performative because it transmitted a clear juridical response to what contemporaries believed were legal challenges.” The violent contestation of a claim to possession of land was a product of the ways in which “juridical perceptions ruled over daily interactions.”Footnote 13

Land and territorial jurisdiction mattered as much to Native communities in colonial Mexico as they did to imperial powers battling one another along their porous boundaries. So too did prestige. In the case of Oaxaca, since pre-Hispanic times, Native municipalities had been ordered in hierarchical and reciprocal relationship to one another. A community's prestige—determined by the land it controlled, the stature of its leaders, and the sumptuousness of its temple and sacred objects—played a central role in the political order.Footnote 14 During the colonial period, violent claims to land were often the provenance of Native officials, the men who held the most prestige and honor within any given municipality. As officers of the Crown, they were duty bound to uphold the law of the realm. As leaders of their community, they were custodians of its semi-sovereignty, land base, and prestige, which they pursued and defended as a sacred obligation to their ancestors. In the case study that follows, I analyze how Native officials and farmers used emblems of authority and everyday objects to claim boundary lands that separated Native communities, ethno-linguistic groups, and colonial districts.

Violence, Objects, and Legal Claims on Ethnic and Colonial Borders

Criminal cases concerning violent altercations in boundary lands provide rich qualitative data regarding the everyday materials of law and their meanings. In the case of Oaxaca, some of these conflicts dragged on for decades or even centuries in episodic cycles of litigation, legal resolution via land titling or contract of co-possession, and violence. These cycles were not unique to Oaxaca or Mexico; they constituted a strategy used by rural communities throughout the early modern Atlantic World to negotiate and struggle over communal land rights.Footnote 15 At the same time, Oaxaca's Indigenous and colonial histories in combination with the region's environment, demography, and economy gave struggles over land—and the everyday materials of those struggles—specific form.

A series of disputes along the ethnic borders between Zapotec (Bènizàa and Bene Xhon) and Mixe (Ayuuk) Indigenous communities and the jurisdictional borders between the Spanish colonial districts of Villa Alta and Tlacolula-Mitla provide a particularly rich example. In December of 1668, the Native authorities of Tepuxtepec, a Mixe town in the Spanish colonial district of Villa Alta, brought a criminal complaint to the Spanish magistrate.Footnote 16 The complaint was serious. It accused Jacinto Lopes, the Native judge of the Zapotec municipality of San Pablo Mitla, an important valley town and parish seat (cabecera) of the neighboring Spanish colonial district of Tlacolula, of injuries and murder. The Tepuxtepec authorities brought the complaint on behalf of their pueblo and especially in the name of Beatriz Peres, the widow of Gabriel Simon, the man who died at the hands of Jacinto Lopes in a field known as Yve Pacam in Mixe, the Native language of the villagers of Tepuxtepec, and “rrancho [sic] del obispo” in Spanish. As was true of much cultivated land across New Spain, the parcel sat at a distance—perhaps a few hours walk —from the town center (Figure 3). The authorities of Tepuxtepec insisted that the people of their community had been cultivating the parcel of land “since time immemorial,” language that signaled a legal claim to the land based on ancient and continuous possession.Footnote 17 At the same time, the language of immemoriality was often used to make a territorial claim when paper titles were lacking and physical manifestations of occupation were the only evidence of possession.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Zapotec community of Temascalapa and distant fields, Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, 2000. Photo by the author.

According to the complaint, Lopes entered the field carrying his staff of office—the premier symbol of his judicial authority—accompanied by an entourage of Indians, all of whom, including Lopes, were armed. There, they encountered Gabriel Simon, seven other men, and a number of women from Tepuxtepec who were “quietly and peacefully” working and minding their own business. Notably, “quietly and peacefully” was also standard legal discourse in claims to possession, signaling that said possession was uncontested. The peace shattered abruptly when Lopes began shouting at and beating the villagers, claiming that the land and jurisdiction was his, and that he was going to kill them all. He warned that even if the Spanish magistrate came to intervene, he would go ahead and do so anyway, because he had five other pueblos in league with him. Next, he ordered the Native constable who accompanied him to tie Gabriel Simon to a tree and beat him. When the constable finished with Simon, he tied the rest of the villagers to trees and left them there the entire night, defenseless against the cold night and the wild animals or bandits who might come upon them.Footnote 19

One of the men was able to escape to Tepuxtepec, where he alerted the community's authorities to what had transpired in the distant parcel of land. The Mixe authorities arrived at the disputed territory at dawn, where they found Jacinto Lopes and his companions. Lopes's constable arrested and bound them, and confiscated their staffs of office. At this point, don Juan García, Governor of Ayutla, a neighboring community, arrived on the scene with Natives from other nearby towns. According to testimony, he asked Lopes “how is it that you have done this, invaded with your staff of office in order to formalize a legal complaint?” García's question implied that Lopes's actions walked a line between the legal and the extralegal. His performance was immediately intelligible to García, while at the same time pushing the boundaries of acceptable practice.

García urged Lopes not to whip the men, but Lopes did so anyway. In an effort to leave no doubt as to the impotence of the officials of Tepuxtepec, Lopes engaged in a final affront to the Mixe authorities’ claims to the “rancho del obispo,” and just as importantly, to their honor: he picked up their staffs of office that he had seized upon their arrest—as well as some other possessions, including their clothes, machetes, a loom, a woolen mantle, axes, tools, and a pig—and returned with them to Santa María. Once Lopes and his entourage were gone, García and other men on the scene freed the bound villagers, but Gabriel Simon, who had suffered the worst of the beating, died shortly after.Footnote 20

As recounted to the Spanish judge by the Mixe officials of Tepuxtepec, this case constituted a violent land grab on the part of Lopes and the Zapotec officials of Santa María. The objects that Lopes and his entourage forcibly took from the Mixe officials and farmers and sequestered back in the confines of their own community reveal how law and violence worked together in this dispute. First, Lopes and company stripped the Mixe authorities of the objects that imbued them with authority and honor: their staffs and clothing. And then they erased the evidence of Mixe occupation and use of the land itself by confiscating farming tools, a loom, and livestock.

In this regard, despite the violence, Jacinto Lopes’ actions were performed using the material trappings of the law and were consonant with many of the practices of colonial Indian jurisdiction. According to the criminal complaint, Jacinto Lopes carried his staff of office into the field in the company of armed men, which suggests that he was intent on carrying out some form of justice, and was prepared to use force if necessary. Spanish colonial law made clear that Native judges had the right to physically punish members of their community for minor crimes. They could even punish individuals who were not members of their community but who committed a crime within its territorial boundaries. In either situation, punishment had to be light, such as six to eight lashes. It is clear, however, that throughout New Spain, Native judges often exceeded the prescription of light punishment, doling out dozens of lashes and in some cases, beatings, for a variety of offenses.Footnote 21

Jacinto Lopes's violent performance pushed the boundaries of Indian jurisdiction even further. Not only did he enter the territory of another community, armed and carrying his staff of office, and punish its members, but he also arrested and whipped the Native authorities of that community who had arrived on the scene to investigate the dispute and supposedly defend their jurisdiction over the contested territory. Native authorities possessed honor, and whipping them was a decidedly dishonorable punishment and a blow against the prestige of the town. Notably, he also confiscated their staffs of office and took them back to his own town.

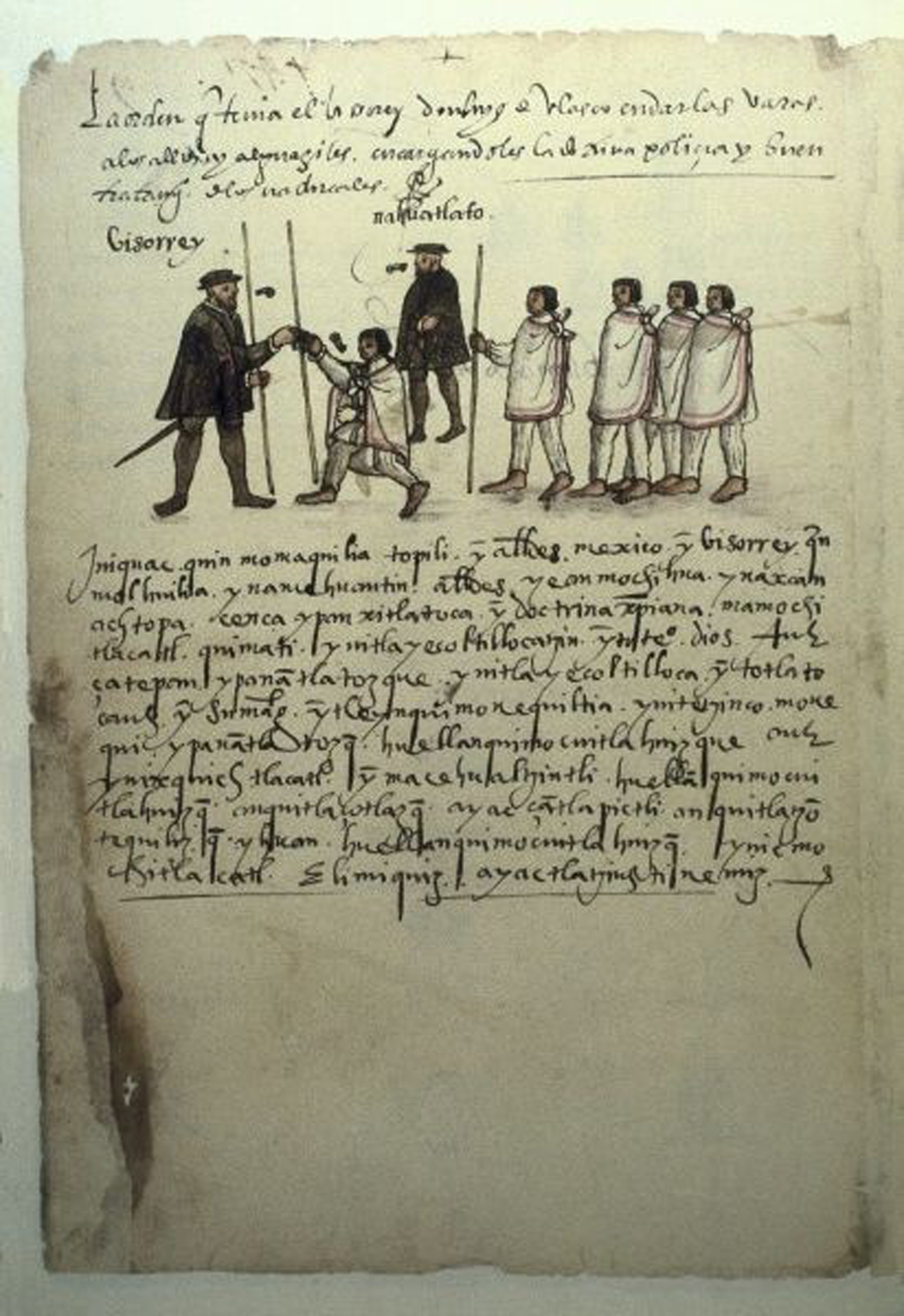

What did it mean for a Native judge to carry a staff of office onto disputed land and forcibly take the staffs of the authorities of another community? The answer lies somewhere between making a legal claim and challenging the sovereignty of another community. Staffs were highly meaningful objects in both pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica and the Spanish Empire. Carrying a staff in the Spanish Empire signaled a vertical relationship with the king such that the bearer of the staff channeled royal authority. Indian officials carried their staffs everywhere they went while they fulfilled a wide range of duties: collecting tribute, inspecting and allocating lands for use by commoners, arresting criminals, taking testimony, or notarizing a last will and testament. The staff literally imbued them with the king's authority, signifying that their actions were approved and legitimized by the Crown (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Viceroy Luis de Velasco and Indigenous leaders with staffs in the Codex Osuna, 1565.

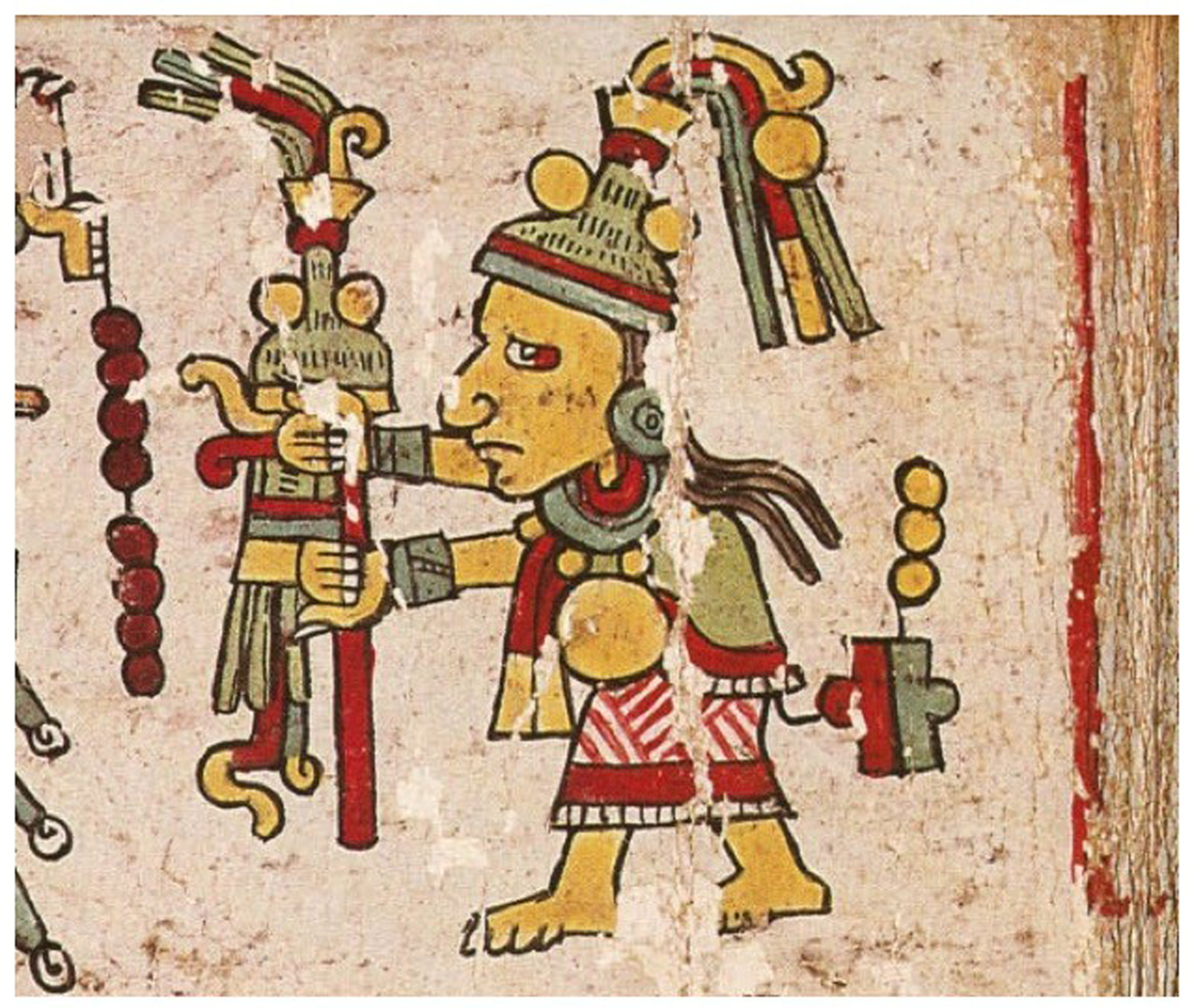

In the hands of Indian town officers, the colonial vara de justicia (staff of justice) carried traces of pre-Hispanic meanings as well. Ethnohistorical studies of Native office holding point to strong continuities between the meanings and functions of Indigenous political authority across the divide of Spanish conquest, and the role of staffs in legitimizing Indigenous authority.Footnote 22 Indigenous pictorial and written records also speak to the local meanings of staffs of justice and the place that they held in historical memory. In the pictographic historical-genealogical records of the Mixtec region of Oaxaca, pre-Hispanic rulers bear staffs as royal insignia and as emblems of their role as intermediaries between the sacred and human realms. Crucially, they also use staffs as ritual implements with which to found ethnic territory (Figure 5).Footnote 23 In pictographic genealogies from Oaxaca's Sierra Norte, staffs distinguish colonial-era rulers from their pre-Hispanic forebears, announcing the territorial foundation of their Spanish-style municipalities and signaling the domain of Indian jurisdiction after conquest.Footnote 24 Staffs also feature centrally in primordial titles, a genre of Mesoamerican writing that recounted the founding of ethnic territory by members of ruling lineages.Footnote 25 As they did in Zapotec pictographic genealogies from the Sierra Norte, staffs symbolized a crucial transition from the pre-Hispanic to Spanish colonial periods in the narratives of primordial titles from the region, most of which follow a similar arc. The titles feature noble ancestors as protagonists who founded ethnic territory through migration and warfare, and who welcomed the conquistador Hernán Cortés and the missionary friars, willingly submitted to baptism, and accepted Christian names. The narratives then feature Spanish officials who named a founding ancestor as governor, established the Native town council (cabildo), and gave Native authorities their staffs of office. The Native officials finally went on to build a church and the seat of the municipal government, divide the lands for use by the community, and mark the territorial boundaries of the community with crosses.Footnote 26

Figure 5. Lady Three Motion (Ñudzahui culture hero/royal ancestor) with staff, Codex Nuttall (also known as the Codex Tonindeye), circa fourteenth century.

The passing of the staffs of office to Native lords by Spanish officials in the primordial titles thus signaled a shift from legitimizing claims to land via warfare and conquest to legitimizing claims to land via Spanish law.Footnote 27 In this way, staffs—infused with new meaning—boundary markers, and colonial law became the new ritual implements for territorial foundation in a new historical era. When Jacinto Lopes and the Native officials of San Pablo Mitla deposed the officials of Tepuxtepec by relieving them of their staffs of office, then, they stripped them of civil, religious, and judicial authority, whose meaning had accreted across the pre-Hispanic and colonial divide. Pointedly, they also stripped these officials of their authority over the land. Had the communities of Tepuxtepec and San Pablo Mitla been sovereign entities as they had been during the pre-Hispanic period, Jacinto Lopes’ actions might have been considered acts of war.

In fact, given the long history of Mixe–Zapotec enmity, it makes sense to read Jacinto Lopes's actions at least in part as warfare channeled through law. In their criminal complaint, the authorities of Tepuxtepec identified their pueblo as part of the “Mixe nation” (“nación mije”). In Oaxaca's Sierra Norte, broad ethnolinguistic identifications—signaled by the Spanish term “nación”—that transcended individual pueblos mattered more in Indigenous socio-political organization, and in determining alliances and conflicts than they did in other regions of Oaxaca.Footnote 28 This was especially so in the case of the Mixe and Zapotecs who were waging a bitter war against one another when the Spaniards made their first attempt at conquering the sierra. When the Spaniards secured military victory in the sierra after multiple, hard-fought incursions along the highland Zapotec frontier, the Zapotecs allied with the Spaniards against the Mixe, who put up fierce resistance.Footnote 29

This history of alliance and conflict privileged the Zapotecs of the sierra in the eyes of the Spanish administration. Whereas the Zapotecs engaged more quickly with Spanish ecclesiastical, administrative, and legal institutions, the Mixe remained on the periphery of the Spanish district of Villa Alta and were considered to be wild and barbaric, not only by Spaniards but also by some of their Indigenous neighbors.Footnote 30 They resisted the imposition of Spanish institutions to the point of violent rebellion against their colonial overlords and Zapotec allies in Villa Alta in 1570, and through a violent millenarian movement directed against the Spanish magistrate of the colonial district of Nejapa in 1660.Footnote 31 Dominican friars who evangelized in the Sierra Norte complained of the recalcitrance of the Mixe population to Christianization, and relatedly, the difficulty in translating the Christian doctrine into the Mixe language, which had distinct variations in some cases at the village level.Footnote 32 As a result of the inability of the friars to impose a standard variety of spoken or written Mixe, Nahuatl—the language of Central Mexico, and lingua franca of the Mexica (Aztec) and Spanish Empires—was used by Mixes and Spaniards as an intermediary language in the court of Villa Alta. This linguistic isolation further marginalized the Mixe and privileged their old Zapotec rivals in their dealings with Spanish officials and institutions.Footnote 33

As a result, the Mixe bore the brunt of the Spanish system of exploitation, including the encomienda system of labor, and the onerous demands of personal service to Spaniards. The Mixe also suffered an especially pronounced fragmentation of their territory during the Spanish colonial period. In the pre-Hispanic era, the Mixe constituted a powerful, decentralized polity that stretched from the southeastern Sierra Norte through portions of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The Spanish–Zapotec alliance that resulted in their military defeat and subsequent marginalization extended to Spanish colonial courts where Zapotec elites and cabildos systematically dispossessed Mixe communities of their lands. The cultural and linguistic isolation of the Mixe and the comparatively quick adaptation of Zapotecs to Spanish ecclesiastical and legal institutions gave the Zapotecs an advantage in these territorial disputes mediated by Spanish courts.Footnote 34

It is tempting then to read the alleged invasion of a Mixe parcel of land by a Zapotec judge accompanied by an entourage of Zapotec Indigenous as an extension of this process of Mixe expropriation. Lopes's staff of office and the judicial whipping that he applied to the hapless Mixe villagers lends the patina of legality to a violent process of dispossession that a century and a half prior might have been carried out through warfare. Lopes's performance of his legal authority, symbolized by the staff and the lash, represented a claim to the boundary lands under dispute. We can therefore read the criminal complaint lodged by the cabildo of Tepuxtepec as a counterclaim.

The conflict on this particular site of the Mixe–Zapotec frontier was more than a dispute among Native communities; it escalated into a conflict between two Spanish colonial administrative districts. Not only did Jacinto Lopes challenge the authority and territorial jurisdiction of the Native officials of Tepuxtepec by claiming that the boundary lands were his and belonged to his “jurisdiction,” but also, even more boldly, he challenged the jurisdiction of the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta, stating that even if the Spanish judge were to intervene, he (Lopes) had five other pueblos in league with him to help him take the land and assert his claim.Footnote 35 Lopes's reference to an alliance of villages —presumably Zapotec villages from the Valley—pointed to socio-political ties that transcended his pueblo, an issue of concern for Spanish authorities who sought to circumscribe and limit Indian identity and political action within the bounds of discrete villages.

Lopes's boast that he would assert his jurisdiction over that of the Spanish magistrate challenged not only the boundaries of Mixe and Zapotec territory, but also the boundary of the Spanish legal-administrative jurisdictions of Tlacolula-Mitla and Villa Alta.Footnote 36 Technically speaking, if the territory did indeed belong to San Pablo Mitla, the Spanish magistrate of Tlacolula-Mitla, not the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta, had jurisdiction over it. By disputing these striated boundary lands, the Native litigants in this case put into motion jurisdictional competition between the two Spanish magistrates.Footnote 37 Spanish magistrates often had vested interests in territorial conflicts between Native villages on the boundaries of Spanish jurisdictions. Since they relied on Native authorities as proxies who collected tribute and exploited the labor of the Native people who resided in their municipalities, control over those people and the land that they worked was of real importance for both the Native authorities and their Spanish overlords. In cases such as these in which both Native and Spanish jurisdictional boundaries were in question, Spanish magistrates often participated. The fact that boundaries between jurisdictions in remote, mountainous regions were often inexact exacerbated the problem.Footnote 38

Since the criminal complaint by the authorities of Tuxtepec against Jacinto Lopes was made in front of the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta, it fell to him to decide the case. After hearing witness testimony, he was ready to take legal action. He dispatched a legal notice to Spanish officials in the district of Tlacolula-Mitla, calling for the arrest of Jacinto Lopes and the two constables who had accompanied him into the disputed territory. He also ordered that the prisoners be brought to the jail in the district seat of Villa Alta, presumably so that a formal case could be brought against them. The fate of the accused—and the resolution of the territorial dispute—remains unknown because the dossier ends there. It could be that the Spanish magistrate of Tlacolula-Mitla eventually cooperated with the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta; Spanish officials often worked together on matters pertaining to criminal justice. But when jurisdictional boundaries etched in territory were at stake, they often competed with one another. It is also possible that the case was decided extrajudicially through a customary process of reparation and reconciliation.

One Hundred and Thirty Years Later

Legal documentation from the 1790s and early 1800s demonstrates that the Mixe community of Tepuxtepec successfully defended its claim to the parcel of land called the “rrancho de obispo” that figured in the 1668 dispute.Footnote 39 However, this legal victory did not ensure peace between Mixe and Zapotec communities along the borders of Spanish colonial districts. In 1798, Mixe authorities of the communities of San Pablo Ayutla, Tlahuitoltepec, Tamasulapan, Tepantlali, and Tepuxtepec complained to the Spanish magistrate of Villa Alta that their Zapotec neighbors from the town of Santo Domingo Albarradas had crossed into their territory and attempted to claim a parcel of land that belonged to the Mixe towns collectively. The Zapotecs of Albarradas did so in spite of the fact that the Mixe towns possessed a legal title, which they submitted with their complaint, and despite the ritualized laying of boundary markers in which Spanish authorities and Indigenous authorities of the surrounding communities participated.Footnote 40

The Mixe authorities detailed the violence with which the Zapotecs of Santo Domingo Albarradas had attempted to lay claim to their lands. According to their testimony, the authorities of Santo Domingo arrested a Mixe alderman and principal (notable) who had been plowing the fields under dispute, and took them forcibly, along with three teams of bulls, two cows, and some yokes, plows, and wheels back to their village. There, they whipped the men in the public square, imprisoned them, and treated them cruelly. After five days, the Zapotec authorities brought a falsified criminal complaint against them to the Spanish magistrate of Teotitlan. With the help of legal counsel, the Mixe authorities obtained their release. They asked the magistrate of Villa Alta to secure the restitution of their livestock and farming implements and compensation for the days of labor that their compatriots missed while imprisoned. They also demanded that their Zapotec neighbors stop burning their jacales (simple huts built in fields for use during sowing and harvest) and destroying their fields of corn, cactus, maguey, and plantains with machetes and through the introduction of livestock.Footnote 41

The tactics deployed by the Zapotecs of Santo Domingo Albarradas conformed to familiar patterns of claiming possession to boundary lands in the Iberian world through destruction of a neighboring community's evidence of occupation: crops, structures, and livestock. In this context, the everyday materials of rural agrarian life took on legal meaning, and the violent struggle to expand and defend communal land bases persisted until some legal resolution was reached: an agreement, a judicial stay, or a land title.

At the same time that the cycle of violence, litigation, and legal rulings repeated itself on the Zapotec–Mixe frontier and the boundaries between Spanish colonial districts, it had intensified within the district of Villa Alta, and among Mixe and Zapotec communities themselves. A regional demographic boom during the eighteenth century, and especially from 1700 to 1742, put more pressure on land, as did the customary practice of inheritance and division of communal lands allotted to individual families, leading to increased parcelization and diminished plot sizes.Footnote 42 In written agreements that resolved land disputes by authorizing co-possession of boundary lands, Native authorities forthrightly acknowledged the desire to avoid the costs and rancor of litigation, and in one instance, expressed the desire to end the state of “civil war” in which they had been living with their neighboring pueblo.Footnote 43

As the century closed, the Mixe communities of Ayutla and Tepuxtepec, who had only recently joined in common cause in the land dispute against Santo Domingo Albarradas, initiated a legal suit over possession of “el rancho de obispo,” the same parcel of land where Gabriel Simon had died at the hands of Jacinto Lopes a century and a half earlier.Footnote 44 The ethnic solidarity that had characterized that and more recent conflicts was counterbalanced by other factors, including demography, agrarian transformation, and administrative change. In 1721, Spanish officials designated Ayutla as cabecera (parish seat), making Tepuxtepec one of its subject towns.Footnote 45 From 1742 to 1789, the population of Tepuxtepec grew from one-hundred sixteen to five-hundred sixteen residents, and that of of Ayutla shrank from eight-hundred and seventy to five-hundred and three.Footnote 46 The authorities of Tepuxtepec had allowed villagers from Ayutla to farm some land within the parcel, but now sought to remove those farmers from the plots. Alongside the need for farmland, competition for prestige between a growing subject town (Tepuxtepec) that had eclipsed the population of a shrinking cabecera (Ayutla) may have factored into the conflict. Allegations of theft of crops and threats of violence coursed through the pages of the criminal record, opening a new chapter in an ongoing territorial struggle underwritten by the Spanish legal concepts of property and possession.

Conclusion

Law and performative violence were constitutive elements of a single legal process in colonial Mexico. Understanding colonial justice in rural, Indigenous settings requires attention to how law and a longue durée history of inter-Indigenous relations patterned violence and object-centered performances in peripheral spaces. The violence inherent in these disputes was cloaked in the judicial authority of the Native officials of the warring communities and was in fact the product of ongoing conflict that had either been adjudicated in Spanish courts or entailed some sort of legal claim. Judicial violence simultaneously expressed inter-ethnic conflict and the juridical perception that inaction or silence when faced with a competing claim to territory implied consent. Violent performances in boundary lands featuring staffs, whips, machetes, fire, livestock, and farming implements worked in concert with litigation, legal titles, and written agreements in ongoing cycles of conflict and resolution.

Spanish law sought to determine possession of land through occupation and use, and fix landed property through titles and boundaries, which Native judges enforced or contested based on their immediate needs, interests, and inter-ethnic histories. But Native justice was also oriented toward asserting community prestige. Territory was as much a part of the economy of prestige as it was cornfield or pasture. So too was the honor of the Native judges who were stewards of their community's prestige. When the prestige of their community was under threat, their role called for the ritual humiliation and dishonor of the authorities of other communities, performed according to the procedures and symbols of criminal law as administered through colonial Indian jurisdiction. One could locate the origins of such performances in pre-Hispanic times, when they belonged to the arena of warfare or civic-religious ritual. But one could also locate their origins in the Spanish legal rationale of possession. Something of both was at work in the cornfields of Oaxaca where Indigenous authorities and farmers forged legal culture and agrarian custom that was at once trans-Atlantic and local.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Greater Atlanta Latin American and Caribbean Studies Initiiatve (GALACSI) and the organizers and participants of “Indigenous (Latin) America: Territories, Knowledge, Resistance, and Voices” hosted by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies and American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois where I presented early versions of this article. I would also like to thank Kalyani Ramnath and my fellow participants in the ASLH 2020 Plenary Session “The Everyday Materials of Colonial Law” for the fruitful collaboration that led to this final version.