Introduction

This article seeks to make a contribution to international debate about the legitimacy and efficacy of hate speech laws, by examining the effects of hate speech laws in practice. Hate speech is condemned in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Art. 19) and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Art. 4). These injunctions have been operationalized in many countries, and studies have been conducted into the operation of hate speech laws in countries including Canada (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2005a, Reference McNamara2005b; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2007: 187–208; Reference Sumner, Hare and WeinsteinSumner 2009), the United Kingdom (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2007: 167–86; Reference Williams, Hare and WeinsteinWilliams 2009), France (Reference Mbongo, Hare and WeinsteinMbongo 2009; Reference Suk, Herz and MolnarSuk 2012), Hungary (Reference Molnar, Hare and WeinsteinMolnar 2009), and Germany (Reference Grimm, Hare and WeinsteinGrimm 2009). In the United States hate speech laws do not exist due to the protections afforded speech by the First Amendment (Reference Heyman, Hare and WeinsteinHeyman 2009; Reference WeinsteinWeinstein 1999), however, there is an excellent literature examining the enforcement of hate crime laws that punish bias-motivated crimes (e.g., Reference Jacobs and PotterJacobs and Potter 1998; Reference Jenness and GrattetJenness and Grattet 2001; Reference LawrenceLawrence 1999; Reference Savelsverg and KingSavelsberg and King 2005, Reference Savelsverg and King2011). There have also been numerous philosophical contributions to this field, which have focussed, for example, on the ways in which hate speech can harm (Reference Maitra, McGowan, Maitra and McGowanMaitra and McGowan 2012a, Reference Waldron2012b; Reference WaldronWaldron 2012) or on debates for or against hate speech laws (e.g., Reference BrownBrown 2015; Reference Heinze and PhillipsonHeinze and Phillipson 2014).

Since the enactment of the first hate speech legislation in Australia in 1989, research has focussed on their compatibility with free speech principles (Reference FlahvinFlahvin 1995; Reference GelberGelber 2002; Gelber and Stone eds. Reference Gelber and Stone2007a; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2002) or the Constitution (Reference AroneyAroney 2006; Reference ChestermanChesterman 2000; Reference MeagherMeagher 2005). Research has also evaluated how the laws are applied and interpreted (Reference ChapmanChapman 2004; Reference ChestermanChesterman 2000; Reference GelberGelber 2000; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 1997; Reference MeagherMeagher 2004; Reference ThampapillaiThampapillai 2010) or case studies (Reference Hennessy and SmithHennessy and Smith 1994; Reference JessupJessup 2001; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 1998). This article aims to update this literature by presenting the findings from a large, new study into the impact of hate speech laws on public discourse in Australia, from the enactment of the first hate speech laws in New South Wales in 1989 to 2010.

We investigate the ways in which legislation might have affected public discourse over time. We note that legislation in Australia is drafted differently in different jurisdictions (see below). This means there is no single legal definition of hate speech in Australia. Further, we were concerned to assess the regulatory system's effects on speech that may stylistically not be challengeable under extant laws, but that nevertheless discursively enacts discrimination or marginalization. We, therefore, use the term “hate speech” to mean expression that is capable of inciting prejudice toward, or effecting marginalization of, a person or group of people on a specified ground (adapted from Gelber and Stone Reference Gelber, Stone, Gelber and Stone2007b: xii). We use it interchangeably with “vilification,” the latter being used in the Australian regulatory framework.

Our task is methodologically challenging, for connecting changes in public discourse to the introduction or enforcement of hate speech laws is fraught with difficulty. We take a measured and careful approach where we make claims about the likely influence of hate speech laws on public discourse. We also acknowledge the need for caution in extrapolating our conclusions about Australia's regulatory scheme to other jurisdictions where different models of hate speech laws have been enacted, and to the United States, where the First Amendment precludes the statutory prohibition of hate speech. Nonetheless, we believe a number of our findings have wider implications. These include our insights about the possibility for instrumental and symbolic benefits even in the absence of punitive sanctions for norm violation, and our reservations about the “uneven” protection afforded by regulatory regimes that adopt a civil justice model, where status as a “victim” is a precondition to commencing proceedings, and where the material conditions and organizational capacity of communities targeted by hate speech can seriously impact on their opportunity to access the law's protection.

This research project triangulated data from a range of primary and secondary sources, to investigate the relationship between hate speech laws and public discourse over time. Sources include complaints data from, and interviews with, federal and state/territory human rights authorities; tribunal and court decisions; qualitative document analysis of letters to the editor published in newspapers; data from community organizations regarding their members’ experiences; and interviews conducted with 101 members and representatives of target communities. These latter interviews were conducted on our behalf by Cultural and Indigenous Research Centre Australia (CIRCA). A total of 55 qualitative, semistructured, in-depth, paired (46) and individual (9) interviews were conducted in urban (41), regional (6), and remote (8) areas.Footnote 1 Interviews were conducted with the following groups: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Afghani, Australian-born Arabic-speaking Muslim, Australian-born Arabic-speaking Christian, Chinese, Indian, Jewish, Lebanese-born Christian, Lebanese-born Muslim, Sudanese, Turkish Alevi, Turkish Muslim, and Vietnamese. The authors also conducted qualitative, semistructured, in-depth interviews with newspaper editors, and lawyers involved in vilification cases. Interviews were conducted under conditions of confidentiality, therefore, no identifying information is provided for interviewees except where they gave us express permission to do so. In each subsection of this article, we provide further information about the method utilised for that component of the data collection.

Australian Hate Speech Laws

Australia is a federation with six states and two self-governing Territories. All jurisdictions except the Northern Territory have enacted hate speech laws. The Australian approach to hate speech regulation has involved the enactment of both criminal and civil provisions against racist hate speech, with many jurisdictions including other grounds such as sexuality, religion, transgender status, disability, and HIV/AIDS status (see Table 1).

Table 1. Chronology of the Introduction of Civil Hate Speech Laws in Australia

There were two major drivers for the enactment of the first hate speech laws in the late 1980s and early 1990s. First, there were concerns about the virulent hate speech being circulated by right wing organizations (such as National Action in New South Wales and the Australian National Movement in Western Australia) (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2002: 121, 222–25). Second, in 1991, the National Inquiry into Racist Violence conducted by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission documented disturbing levels of racism directed at ethnic minority and Indigenous communities, which manifested in harassment, intimidation, fear, discrimination, and violence (AHREOC 1991). Although the introduction of hate speech laws raised concerns about their implications for freedom of expression, legislatures were motivated to act on the basis that existing laws were seen to be inadequate to sanction and deter public expressions of racism, and out of a determination symbolically to mark Australia's commitment to multiculturalism and principles of equality and nondiscrimination (ALRC 1992; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2002: 18–20).

The extension of protection to other grounds through the 1990s and 2000s was either part of a wider updating of the jurisdiction's primary antidiscrimination statute (e.g., in Tasmania) or a response to local concerns about the prevalence of hate speech. For example, New South Wales extended hate speech laws to cover homophobic hate speech in the early 1990s in response to a reported increase in the prevalence of homophobia and gay bashing. During parliamentary debate Independent MP Clover Moore documented a large number of cases of serious of homophobic violence in Sydney and observed, “Public acts which incite hatred of lesbians and gay men feed into the violence against lesbian and gay men” (Hansard, NSW Parliament, Legislative Assembly, March 11, 1993).

Although criminal laws have been implemented in several subnational jurisdictions, in those that possess both criminal and civil laws the criminal laws have never been successfully invoked (Reference Gelber, Gelber and StoneGelber 2007: 8; NSW Legislative Council 2013: xi). The criminal laws in New South Wales,Footnote 2 Queensland,Footnote 3 and South Australia,Footnote 4 prohibit conduct that incites hatred, serious contempt or severe ridicule, and simultaneously involves physical harm or the threat of harm, or inciting others to threaten physical harm toward a person, a group of persons, or their property. VictoriaFootnote 5 criminally prohibits conduct that incites hatred and threatens, or incites others to threaten, physical harm toward a person or their property. In the Australian Capital Territory,Footnote 6 the criminal law prohibits threatening conduct that intentionally and recklessly involves the incitement of hatred, serious contempt or severe ridicule. These provisions have never resulted in a successful prosecution, due primarily to the high hurdle requisite to a criminal offence (NSW Legislative Council 2013: xi).

As an interesting counterpoint, Western Australia possesses only criminal hate speech laws,Footnote 7 and is the only jurisdiction in which successful criminal prosecutions have occurred. The laws create two-tiered offences (based on the existence or not of intent) of conduct that incites racial animosity or racial harassment, possession of material for dissemination that incites racial animosity or racial harassment, conduct that racially harasses, and possession of material for display that racially harasses. There have been three successful prosecutions: one for possession of racist material in 2005 (Reference Gelber, Gelber and StoneGelber 2007: 8); a guilty plea to “conduct likely to racially harass” in 2006 (ODPP WA 2011); and a prosecution for “conduct intended to incite racial animosity or racist harassment” and for “conduct likely to racially harass” in 2009, which was unsuccessfully appealed in 2012.Footnote 8

The civil laws carry the practical regulatory burden (Reference Gelber and McNamaraGelber and McNamara 2014a). Australia's national hate speech lawFootnote 9 relevantly states:

1. It is unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if:

a. the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people; and

b. the act is done because of the race, color or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.

While the harm threshold may appear relatively low, case law has established that the standard to be met is conduct that has “profound and serious effects, not to be likened to mere slights.”Footnote 10 Also, exemptions apply to artistic, academic, scientific, and journalistic conduct, done in good faith.Footnote 11

New South Wales was the first jurisdiction to enact a hate speech law in 1989:Footnote 12

20C (1) It is unlawful for a person, by a public act, to incite hatred toward, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule of, a person or group of persons on the ground of the race of the person or members of the group.

There is an exemption for:

a. a fair report of a public act referred to in subsection (1), or

b. a communication … that would be subject to a defence of absolute privilege … in proceedings for defamation, or

c. a public act, done reasonably and in good faith, for academic, artistic, scientific or research purposes or for other purposes in the public interest, including discussion or debate about and expositions of any act or matter.

With some variations, the NSW model has been followed in Queensland,Footnote 13 Tasmania,Footnote 14 Victoria,Footnote 15 the Australian Capital Territory,Footnote 16 and South Australia.Footnote 17

The civil laws require a person who believes an incident of hate speech has occurred to lodge a complaint in writing with a human rights authority (e.g., the Anti-Discrimination Board in New South Wales, or the Australian Human Rights Commission under federal law). The authority investigates the complaint to ascertain whether vilification has occurred, and seeks to conciliate a confidential settlement between the complainant and respondent. The kinds of remedies that can be provided include an agreement to desist, apologise, or publish a retraction, or to conduct an educational campaign in a workplace. A complainant may terminate a complaint and commence civil proceedings in a tribunal (in a state or Territory) or the Federal Court (under federal law). Less than 2 percent of hate speech complaints are formally adjudicated and half of those produce findings that the conduct complained of was unlawful (Gelber and McNamara Reference Gelber and McNamara2014a: 314). If the tribunal/court determines that the conduct in question is unlawful hate speech, it can order an apology, an order to desist, the payment of damages,Footnote 18 or the publication of a corrective notice. For a complaint to be valid the conduct must have occurred in public, with case law generally interpreting this to mean that it needed to be reasonably foreseeable that a member of the public could have heard the conduct in question (Reference Chapman and KellyChapman and Kelly 2005: 207–8, 210–13).

The locus of enforcement responsibility under Australia's regime of civil hate speech laws rests with the victims. Legislation can only be invoked by an individual or representative organization from the group that has been subjected to hate speech. In sharp contradistinction to the responsibility of the state to investigate and prosecute alleged hate crimes (Reference Jenness and GrattetJenness and Grattet 2001), under Australia's civil hate speech laws no state agency has the authority to initiate a complaint or to pursue litigation (Reference Gelber and McNamaraGelber and McNamara 2014a: 307).

Australia's primary reliance on a civil approach that is able to respond to a greater range of hate speech than criminal laws makes it a particularly interesting focus for analysis. We analyse Australia's hate speech laws against five commonly advanced claims about their likely effects. Our findings in relation to the complaints mechanisms are drawn from complainants’ experiences with the civil laws, and the findings in relation to other areas are drawn from the entirety of the regulatory framework.

Five Claims About the Effects of Hate Speech Laws

In this article, we focus on five of the most important and cogent claims made about the likely effects of hate speech laws. Although we have disaggregated the data our study has produced against the heuristic of these claimed effects, the findings in relation to one are also relevant to others.

The first claim is that hate speech laws provide a remedy to targets of hate speech. Australian laws are sufficiently broad to include both personally targeted vilification directed at an individual or a group, as well as speech that puts into circulation discriminatory views. This reflects the fact that the laws are designed to provide a remedy for both the personal assault on dignity experienced by targets, and the enhanced risks of discrimination and violence that flow from allowing discriminatory stereotypes to circulate publicly. Of course, attempts to sanction the latter are regarded as anathema in the United States on First Amendment grounds, but in Australia they fall squarely within the purview of hate speech laws.

It follows that, in considering whether laws in Australia provide a remedy to the targets of hate speech, we consider two conceptions of “targets.” The first are individuals who have been personally targeted, whether face-to-face, or by being named in a statement communicated to the public (e.g., newspaper article, radio program, Web site). The second are members of a targeted group, whether or not they individually were subjected to, or heard, the conduct in question. A person may lodge a complaint regarding conduct they consider constituted public hate speech as long as they are a member of the group that the speaker sought to vilify. If a complaint reaches a state/Territory tribunal for determination, the test to be applied is whether the conduct in question can reasonably be considered capable of having incited hatred under the relevant legislative definition. The question of whether any person actually was so incited is immaterial. Given the emphasis that Australian civil hate speech laws place on victim-initiation of legal proceedings, we will consider the literature that suggests that whether or not an affected community (a “community of interest”) has the expertise and resources required to pursue civil litigation successfully is likely to be an important influence on whether hate speech laws provide a remedy (Reference Baumgartner and LeechBaumgartner and Leech 1998; Reference BrowneBrowne 1990; Reference Schlozman, Verba and BradySchlozman, Verba, and Brady 2012; Tichenor and Harris 2002–2003).

The harms that the laws are designed to remedy include those made well-known by critical race theorists, who, inter alia, have argued that being subjected to hate speech is analogous to “spirit murder,” meaning that hate speech enacts “disregard for others whose lives qualitatively depend on our regard” (Reference WilliamsWilliams 1991: 73). Matsuda has written persuasively of the psychological distress, emotional symptoms, restrictions on freedom of movement and association, and risks to self-esteem incurred by targets of hate speech (1993; see also the excellent review of harms in Maitra and McGowan Reference Maitra, McGowan, Maitra and McGowan2012a, Reference Waldron2012b: 4–8). Reference Delgado, Matsuda, Lawrence, Delgado and CrenshawDelgado (1993: 57) has emphasised that “direct, immediate, and substantial injury” may be caused whether or not there is a “fighting words” dimension or risk of immediate public disorder associated with hate speech. This view is supported by Reference Parekh, Herz and MolnarParekh (2012: 41), who argues it is a “mistake, commonly made, to define hate speech as only that which is likely to lead to public disorder.” Certainly, Australian hate speech laws are not limited to conduct that threatens a breach of the peace. Rather, they aim to remedy the harms done to targets as well as wider indirect harms, including marginalization and discrimination.

A second core idea is that hate speech laws will, or ought to, have a constructive effect on public discourse by encouraging more respectful speech. Such laws are not designed to silence discussion on controversial topics, but to underpin an obligation to present opinions in a “decent and moderate manner” (Reference Post, Hare and WeinsteinPost 2009: 128). Prior research in Australia has suggested precisely that they are designed to proscribe “incivility in the style and content of publication of racist material” (Reference ChestermanChesterman 2000: 226), or even that, in attempting to regulate for civility, they privilege the “racist acts of social elites” (Reference ThorntonThornton 1990: 50), although other research has suggested these interpretations are too narrow (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2002; Reference MeagherMeagher 2005).

The third alleged effect of hate speech laws that we will consider is whether they have an educative or symbolic value. This is the idea that the laws make a statement by government that discourse of a certain type is unacceptable. Jeremy Waldron has described this goal as a publicly expressed commitment to uphold people's dignity (2012: 16). Importantly, this claim is independent of whether hate speech laws are invoked in any particular instance. The latter point has been made by Gould in relation to speech codes on university campuses in the United States. Reference GouldGould (2005: 175) has argued that although such codes may be rarely formally invoked, they have an educative effect:

… [T]he very adoption of hate speech policies has influenced behaviour … This point was repeated to me by many administrators at the schools I visited, who reported the rise of a “culture of civility” that eschews, if not informally sanctions, hateful speech. “Don't mistake symbolism for impotence,” they regularly reminded me. … Adopting a hate speech code … could have persuasive power even if it were rarely enforced.

The fourth claim is that these benefits can be achieved without producing a “chilling effect” on speech. The fifth is that the risk of creating “martyrs” is outweighed by the potential for authoritative condemnation of hate speech. These claims are rebuttals of two of the primary objections made by opponents of hate speech laws. As Reference SchauerSchauer (1978) has pointed out, many laws are designed to “chill” in the sense of deterring people from engaging in harmful behavior. Chilling of this sort is considered to be laudable. Critics of hate speech laws use the term “chilling effect” in a pejorative sense, connoting that individuals might be discouraged from engaging in legitimate political debate for fear of falling foul of legislation that proscribes hate speech (1978: 690). The risk of creating martyrs has been explained as follows:

… [J]udicial determinations of guilt or innocence under “hate speech” laws have social implications that … can create “martyrs” of those who would incite discrimination and can claim to have been unjustly silenced by the state … such offensive expression is given more public attention than it might otherwise have received. Amnesty International, 2012: 7–8; see also Reference HeinzeHeinze 2013

Proponents of hate speech laws claim that neither of these risks represents a compelling argument against creating legal regimes for delineating forms of unacceptable speech, and that they overstate the potentially negative effects of hate speech laws and downplay their benefits (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 1994).

A Remedy for Harms?

The first question to consider is whether Australia's hate speech laws provide a remedy. There are two ways in which we construe a “remedy.” The first is whether targets are able successfully to lodge complaints for incidents of hate speech and achieve an outcome that ameliorates its effects. The second is whether the laws have contributed to a reduction in the frequency or virulence of hate speech.

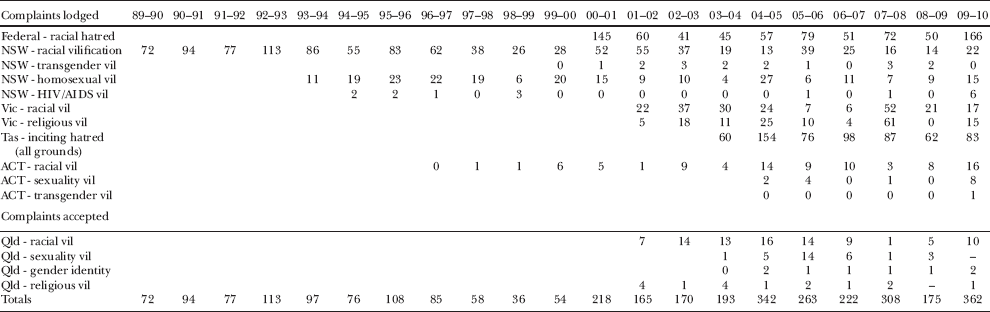

A useful starting point in answering the first question is the number of complaints lodged with authorities since the laws were introduced. Table 2 shows complaints data from those jurisdictions with civil hate speech laws. We do not include South Australia because no complaint has ever been lodged under its tort action civil law, Western Australia because it only has criminal laws, or the Northern Territory because it does not have any hate speech laws. We contacted relevant authorities to obtain these data, since they are not publicly available. We were only able to list the categories held by the authorities; hence the category of “complaints lodged” in most jurisdictions, versus “complaints accepted” in Queensland. Some complaints that are lodged are rejected by the authority as lacking merit, or on procedural grounds (such as the complainant not being from the target group). However, there is no way to identify only the numbers of complaints accepted in those jurisdictions that do not disaggregate their data, because privacy laws prevent researchers gaining direct access to complaint files.

Table 2. Total Numbers of Civil Complaints by Jurisdiction

Several things are noticeable. First, the number of complaints in any given year is relatively modest. In the decade up to 2010 the total number of complaints nationally fluctuated from a high of 342 to a low of 165 per year. These are relatively modest numbers of complaints, given the size of the Australian population at approximately 20 million, and the extent of anti-vilification laws that cover most jurisdictions and a variety of grounds.

Second, there appears to be a trend shortly after new legislation is introduced to test it out, as evidenced by relatively higher numbers of complaints compared with later periods. For example, the year 2004–2005 shows a significant increase in the numbers of complaints compared with the previous year. Nearly half of these complaints were in one jurisdiction—Tasmania—and occurred shortly after the introduction of that state's anti-vilification laws. This peak is, thus, explicable as an example of the higher use of a complaints mechanism shortly after its introduction.

It may be that the higher use of the law in the first few years after it is introduced is due to a heightened awareness of the newly enacted legislation, combined with a desire to test its utility and application. This suggestion was supported by Jeremy Jones, who, as an elected official of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry (ECAJ), has been instrumental in invoking racist hate speech laws to address antisemitism. Jones told us in interview that when the laws were first introduced, their organization looked at, “where do people feel most unable to respond as individuals, and where are we getting people saying we have to do something?” (Reference JonesJones 2013) These cases were pursued and clarification of key aspects of the law's operation obtained, including the threshold required for an incident to be actionable, that material on the internet was covered by the provisions, and that Holocaust denial was prohibited. Subsequently, the community was able to use those judgments in combatting other incidents:

You have a newspaper that's published something, you say, “look at the rules, look at this judgment”, and people say … “we didn't know, we didn't realise, now we do, we don't want to break the law.”

The judgments were used as a tool of advocacy to convince people not to engage in vilification. This was the case even though less than 2 percent of matters are resolved by formal adjudication in a tribunal or court, and, therefore, produce judgments that are released publicly. Where matters are resolved by confidential conciliation, there is very limited opportunity to use these outcomes for educational purposes. The human rights authorities report on some anonymised case studies in their annual reports, but do not release data that list how many hate speech complaints they have dealt with or what those complaints involved. This contributes to what we discovered in interviews with members of targeted communities: that public awareness of the existence and nature of hate speech laws is uneven and, in some communities, low.

It is clear from Table 2 that the number of complaints drops off over time, at times significantly. In New South Wales, 2009–2010 saw only 22 complaints of racial vilification lodged. There are a number of possible explanations for this drop off. One is that there is less need for the active engagement of the law because the community improves its discourse. This was the view recently expressed by a former Attorney-General for New South Wales. Commenting on public submissions to a review by that state of its never-prosecuted criminal anti-vilification laws, Mr Dowd said the decline in the number of complaints over time indicated that the law was achieving its educative purpose (Reference MerrittMerritt 2013: 25).

However, there is evidence to contradict this assertion. First, previous research has shown that the majority of hate speech matters terminate before a conciliation is achieved, due in part to some complaints lacking substance, but more usually to procedural barriers including the need to identify and locate the respondent, and the long time that it can take before a complaint reaches conciliation in some jurisdictions (Reference GelberGelber 2000: 18; Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2002: 158). Second, there is evidence that the incidence of hate speech in the community has remained at concerning levels. Numerous reports from community organizations have pointed to ongoing high levels of verbal abuse suffered by target communities. For example, Jeremy Jones, who has for twenty years maintained a database on incidences of antisemitic “racist violence,”Footnote 19 recorded a significant increase in verbal harassment from 8 in the year ending September 1990, to 128 in the year ending September 2011 (Reference JonesJones 2011).

Three national reports on the health and well-being of same sex attracted people report high numbers of sexuality-based hate speech. The 1998 report noted that 46 percent of respondents had experienced verbal abuse, defined as single-word stereotypical remarks, two-word insults, or threats of violence (Reference HillierHillier et al. 1998: 34). In 2005 the equivalent figure was 44 percent (Reference Hillier, Turner and MitchellHillier, Turner, and Mitchell 2005: 35), demonstrating little change over a seven year period during which sexuality anti-vilification laws were introduced in Tasmania (in 1998), Queensland (in 2002), and the Australian Capital Territory (in 2004). The 2010 report noted an increase in verbal abuse to 61 percent of respondents (Reference HillierHillier et al. 2010: 39). A separate survey of homophobic and transphobic abuse in Queensland reported that 73 percent of respondents had experienced verbal abuse during their lifetime (Reference Berman and RobinsonBerman and Robinson 2010: 33). A 2011 survey of 591 people in the LGBTI communities in New South Wales reported that 58.4 percent of respondents had experienced, “mean, hurtful, humiliating, offensive or disrespectful comments” in public from a stranger (ICLC 2011: 14). Among transgender respondents, nearly 60 percent reported having experienced discriminatory or offensive comments in public (ICLC 2011: 15). In contrast, the complaints data from Queensland and the ACTFootnote 20 show complaints on the ground of sexuality in Queensland ranging from one in 2003/04, to a high of 14 in 2005/06, and then reducing again to three in 2008/09. In the ACT the figures are two in 2004/05, four in 2005/06, zero the following year, one in 2007/08, zero again the following year and eight in 2009/10. The complaints data, therefore, do not track with these reports’ findings in terms of the levels of verbal abuse being experienced.

There are continuing incidences of prejudicial expressions against Arabs and Muslims. In 1998, a report noted that the 1990 Gulf Crisis had created an atmosphere that was conducive to the “scapegoating” of Arab and Muslim people (AHREOC 1998: 119). A 2004 report on religious diversity noted that while in some areas religious communities cooperated well and interfaith initiatives were burgeoning, nevertheless the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 had “triggered an Australia-wide spate” of abuse, hate mail and assault. Veiled Muslim women were a particular target and reported an inability to venture into public (Reference CahillCahill et al. 2004: 79, 81, 84–5, 90). These findings were replicated in our interviews with members of Arab and Muslim communities who stated that since the 2001 terrorist attacks, members of the wider community felt that it was acceptable to engage in verbal abuse toward them, in part because political leaders were also doing so.

Finally, reports on the experiences of Indigenous Australians demonstrate that verbal abuse is persistent and ongoing. A 2012 report in Victoria noted that 92 percent of respondents had experienced being called racist names, or being subjected to racist comments or jokes in the previous 12 months (VHPF 2012: 2). In our interviews, Indigenous people confirmed that they were routinely subjected to verbal expressions of racism that were disempowering, including children in school. This means that it is unlikely that the decline in the number of formal complaints under the civil hate speech laws over time reflects an improvement in the quality of public discourse or a reduction in incidents of hate speech.

Further insights about whether hate speech laws provide redress for targets can be gleaned from examining the sorts of incidents that result in tribunal or court adjudication, and the experiences of individuals who have pursued litigation. One important indicator is the nature of the cases that are referred to tribunals or courts after conciliation has failed or been deemed unsuitable. Early tribunal/court cases provided useful interpretations of the law.Footnote 21 In more recent years, however, while such cases still occur,Footnote 22 they have become less common and a larger number arise out of vilifying comments in the context of a dispute between neighbors or acquaintances,Footnote 23 or in the workplace, where vilification arises alongside an employment discrimination complaint.Footnote 24 Of course, these are serious matters, and the targets of such abuse are entitled to seek redress. It is worth noting, however, that the legislative requirement that the conduct is a public act can loom as a barrier in personal abuse cases.Footnote 25

We also conducted interviews with “successful” complainants/litigants and their lawyers. These showed that the complaints most likely to achieve the remedy sought and advance the wider objective of deterrence have occurred when the complainant is supported by a representative organization, or has exceptional personal resolve to pursue the matter; and where the person alleged to have engaged in unlawful hate speech is an “ordinary” member of the community, rather than a high profile public or media figure. This is because of the commitment required to pursue a complaint to a successful conclusion, and the likely amenability of the respondent to change their behavior in a system that relies heavily on voluntary compliance with a conciliated settlement. For example, Jeremy Jones reported to us that the ECAJ had had good results from a case they had pursued against a recalcitrant antisemite who handed out pamphlets in rural Tasmania.Footnote 26 Prior to lodging this complaint, Jones had received 10 to 15 complaints per year from the area in which she lived. Since she was ordered by the Federal Court to desist, he has received between zero and two.

Successful deployment of hate speech laws ideally relies on an extraordinary individual, backed by a well-respected organization that provides credibility, resources and expertise. As Jones observed with reference to the case in Tasmania, their first litigated “win” under federal racial hate speech law,

… we had the advantage of an individual [Jones] who had been dealing with this stuff for twenty or more years at that time, We had a lawyer who is very used to industrial law but there were enough similarities and a barrister who had a lot of experience in defamation … For an average member of the public to use the law [is] extremely difficult.

Jones adds that because he had been documenting antisemitic incidents for years, the ECAJ had an evidence base to support informed, strategic decisionmaking about which matters should be litigated. No other community affected by hate speech in Australia has documented the problem to the same extent.Footnote 27

We do not suggest that hate speech laws can only be successfully invoked in these circumstances. There is evidence to the contrary.Footnote 28 However, our interviews with litigants and members of targeted communities supported this view. Community legal centres told us that complainants often have excessively high expectations in the beginning of the process when they tend to seek genuine apologies and little else. Over time, however, they can become frustrated, and eventually they may request additional remedies such as damages. A great deal of time and effort is involved in bringing a complaint to fruition—the first successful HIV/AIDS vilification case in New South WalesFootnote 29 took three years from the complaint being lodged to a resolution being ordered in a tribunal. The solicitors assisting the complainants told us, “the stress that JM and JN went through you wouldn't wish on anybody. And they were the victims” (HALC 2012). The complainants had worked in a fast food outlet in a small town, but were forced to relocate due to the dispute. Then, although they were awarded damages, the respondent was in receipt of government benefits and was unable to pay. The victory for the complainants was pyrrhic. Members of targeted groups also told us they found the process difficult, saying, “you might win in the end, but it's going to take so much out of you,” and “it is [worth having the laws] but applying them is another story.” In addition to the time and effort required to take the complaint through to completion, an unrepentant offender may participate insincerely in drafting an apology which they are ordered to offer, which also frustrates complainants who seek a genuine acknowledgement of wrongdoing (HALC 2012; ICLC 2013).

Keysar Trad's long-running battle with radio personality Alan Jones provides another example of the heavy burden carried by complainants/litigants. In April 2005, Jones made statements during his Sydney radio broadcasts including calling Lebanese Muslims “mongrels” and “vermin,” and saying they “hate our country and our heritage,” “have no connection to us,” “simply rape, pillage and plunder a nation that's taken them in,” were a “national security problem” who were “getting away with cultural murder,” and making women feel unsafe and threatened. Trad, a well-known member of Sydney's Lebanese Muslim community, lodged a complaint with the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board and later commenced proceedings in the NSW Administrative Decisions Tribunal. The Tribunal ruled in 2009 that Jones’ statements breached racial vilification law, and ordered an on-air apology, the payment of $10,000 damages, and “a critical review of [Harbour Radio's] … policies and practices on racial vilification and the training provided for employees.”Footnote 30 An appeal by Alan Jones was dismissed in 2011, and in 2012 the Tribunal finalised the terms of an apology. On December 19, Reference Waldron2012, seven and a half years after the offending conduct, Jones read out the apology during his 2GB radio program. Journalist David Marr observed that, “Much of the delay was due to intense - but largely fruitless - legal skirmishing by 2GB” (Reference MarrMarr 2009), a view that was also expressed to us by Reference TradTrad (2013).

But the legal proceedings continued. In 2013, 8 years after the incident, the parties returned to the Tribunal to argue costs. The Tribunal is usually a “no costs” jurisdiction (i.e., each party is responsible for their own legal costs irrespective of whether they win or lose) but an application can be made. The Tribunal ordered the respondents to pay legal costs incurred by Trad after June 2007 (the date on which a reasonable settlement offer made by Trad expired)Footnote 31 and the Appeal Panel ordered that the respondents pay half of Trad's appeal costs.Footnote 32 In November 2013 the NSW Court of Appeal upheld an appeal by Jones and Harbour Radio on the ground that the Tribunal had failed to identify the audience to which the act was directed, and, therefore, the likely effect of the broadcast on an ordinary member of that audience.Footnote 33 Trad was ordered to repay the damages and the complaint was remitted back to the Tribunal for determination. In December 2014, Trad's complaint was again upheld.Footnote 34

These stories confirm that Australia's primary model of hate speech regulation places a heavy burden on the targets of hate speech. The legislation can only be invoked in relation to a given incident if a member of the vilified group is willing to step up and take on the arduous, stressful, time-consuming, and possibly expensive task of pursuing a remedy on behalf of the wider community. In a sense, the regulatory model assumes the existence of such a person in each of the targeted communities. As a result, and reflecting a widely recognised phenomenon in the literature on organized interests (Reference Gilens and PageGilens and Page 2014; Schlozman, Verba, and Reference Schlozman, Verba and BradyBrady 2012), the benefits of the protection of Australian hate speech laws have been unevenly distributed, depending on the ability and willingness of the affected community to pursue hate speech litigation.

Overall, this analysis indicates that civil hate speech laws are providing a remedy, in two senses. The first is that complaints can be lodged and in some cases a favorable outcome obtained. The ability to have a governmental authority validate the message that hate speech breaches the law is important in and of itself, since it provides targeted communities with the knowledge that the law can assist in protecting them from discrimination. The second is in terms of the laws’ educative role. That this educative role includes directly using precedents to dissuade hate speakers is of particular interest, since it would not be able to occur in the absence of hate speech laws. Given the ability of the civil hate speech model to target a wider range of expressive conduct than a purely criminal model would permit, this is particularly important. It provides direct evidence of the educative role that hate speech laws can play. The remedies are, however, limited as there are persistent, significant levels of hate speech, the burden on complainants in seeing a complaint through can be high, and there is an uneven distribution of the benefits among target communities.

A Modification of Speech?

We now consider other evidence regarding whether an improvement of discourse has occurred. We have already established that hate speech is ongoing. Here, we provide further data to consider whether there has been a reduction in hate speech over time.

We conducted a qualitative document analysis of 6,612 letters to the editor published in newspapers in each jurisdiction over the period of the study (Reference Gelber and McNamaraGelber and McNamara 2014b). There is a difference between language use in the mediated outlets that are newspapers, and language use on the street (explicated above). We view the letters to the editor as a mediated discourse that demonstrates the tension between publishing views of members of the public on the one hand, and remaining within the confines of legally permissible expression on the other. We found that the letters pages often contain a disclaimer declaring that the newspaper has published letters roughly in proportion to those received. Our confidential interviews with journalists supported this claim, although they told us that shifts in what they considered permissible to publish were driven by broad social factors, and had little or nothing to do with hate speech laws. This was contradicted, however, by the fact that media outlets routinely train their staff in the legal limits on what may be published—including hate speech laws. Combined, this means we can be relatively confident that the letters published are not a selective subset of letters received, that they reflect changes in language use by letter writers themselves, and that hate speech laws form part of the regulatory environment in which publication decisions are made.

We sourced letters to the editor by constructing a list of events in relation to which it was likely that public commentary might reflect attitudes toward minority groups, including debates about native title, same sex marriage, asylum seekers, and racially identified criminals. We collected all letters to the editor published in the two week period subsequent to each event in the main newspaper/s from each capital city (Sydney Morning Herald, Daily Telegraph, Age, Herald Sun, Mercury, West Australian, Canberra Times, Adelaide Advertiser, Courier Mail) as well as the sole national newspaper (Australian).

We analysed the latent content of the letters, undertaking a qualitative assessment of documents as a kind of discourse analysis (Reference Breuning, Ishiyama and BreuningBreuning 2011: 492) and that seeks to categorise language use in order to understand political behavior (Reference Chilton, Schäffner and van DijkChilton and Schäffner 1997: 211; Reference van Dijk and van Dijkvan Dijk 1997: 2). We read the letters in their entirety to assess the overall message being conveyed by the writer. We identified the use of particular words to show changes in language use over time, and assessed whether the views being expressed in the context of the whole letter were “anti-prejudicial” (condemnatory of prejudice), “prejudicial” (expressing prejudice), or “unbiased” (discussing the relevant policy issue in a manner that did not either condemn or express prejudice). There is inevitably some subjectivity involved in this method, nevertheless its benefits are that it permits a depth of analysis to be applied, and produces more nuanced research data (Reference Sproule and WalterSproule 2006: 116–17). All coding was initially undertaken by one author, ensuring stability (Reference Breuning, Ishiyama and BreuningBreuning 2011: 494). Subsequently the second author conducted an inter-coder reliability test on a random selection of 180 letters (2.7 percent of the total). The test produced a ratio of coding agreement of 0.78, indicating a significant level of agreement, and one well above chance. This ratio of coder agreement produced a Cohen's Kappa reliability factor of 0.660, indicating substantial agreement (Reference Landis and KochLandis and Koch 1977: 165).

Our analysis showed, first, that writers of letters to the editor demonstrate knowledge of hate speech laws, and a connection between those laws and the expression they are using. This is indicated both by the presence of terms related to the laws, and the timing of the emergence of those terms to coincide with the introduction, or expansion, of hate speech laws. However, the terms vilification and hatred were often used in ways that do not conform to the definition of hate speech upon which our study relies, or with legislative definitions (e.g., “vilification” was used to describe criticism of United States’ foreign policy).

Second, we found a sustained shift over time in the language used to express sexuality-based prejudice. In 1994, letters expressing sexuality-based prejudice used terms like “sodomy,” “those who must be restrained,” and “sick act of homosexuality.” In contrast, in 2004 letters expressing sexuality-based prejudice used terms such as “unusual family setups,” “lifestyle choice,” and “alternative models for family life.” This change was consistent from the mid 1990s onward. We found a discernible, but less sustained, shift in language used to express prejudice toward Indigenous peoples. In the early 1990s terms such as “uncivilised” and “not civilised” were in prejudicial letters. By the mid 1990s prejudice was primarily conveyed by referring to “frivolous title claims,” “special laws for Aborigines,” the “Aboriginal guilt industry,” and the stolen generations “myth.” We found no consistent shift in language used to express prejudice toward recent migrants, with expressions including “send migrants back where they came from,” “ethnic crimes,” “noisy minorities,” and descriptions of asylum seekers since c2000 including “human evil,” “illegal immigrants,” “terrorists,” “uninvited intruders,” and “queue-jumpers.”

It is interesting that the most durable shift in language use has occurred not in relation to race, which is a ground in all jurisdictions, but in relation to sexuality, which has been a ground for a shorter period of time and in fewer jurisdictions (see Table 1). This suggests a combination of social forces at work. This is particularly indicated by a more rapid decline in the expression of sexuality-based prejudice in letters published in Tasmania, a state in which a prominent community campaign resulted in the decriminalization of homosexuality in 1994, and the first enactment of anti-discrimination laws that included anti-vilification provisions on the ground of sexuality in 1998. In the 1992–1997 period, the proportion of prejudicial letters published in Tasmania was 84.6 percent and in the 2004–2009 period, it was 50 percent. In the same timeframe in all newspapers, the proportion of sexuality-based prejudicial letters declined from 43.24 percent to 31.6 percent. This indicates that the reduction in sexuality-based prejudicial letters did not occur at the same rate in every jurisdiction. A likely explanation for the more rapid decline in Tasmania is the combination of a successful civil society campaign and the introduction of new laws protecting against discrimination and vilification. Perhaps also (given the connection we were able to make between the letter writers’ views and the existence of hate speech laws) the laws had an educative influence. Of course there were multiple social influences at play, and we do not seek to overstate the part that hate speech laws played.

A third finding is that, in the total population of letters analysed,Footnote 35 there was a modest but significant reduction in the expression of prejudice over time. When the letters are divided into three equal time periods, the proportion of “prejudicial” letters published in 1992–1997 was 33.86 percent, in 1998–2003 the figure was 29.08 percent and in 2004–2009 the figure was 28.54 percent. This reduction in the expression of prejudice is a beneficial outcome. While some might still oppose the right, for example, of same sex couples to marry, as noted one of the aims of hate speech laws is not to shut down debate on controversial issues of public policy, but to assist in generating a debate that does not vilify. What has been captured by our analysis is not the expression of views opposing or supporting (e.g.) same sex marriage, but whether in expressing their views, the writer engaged in hate speech. Of course, our data cannot tell us clearly the extent to which hate speech laws themselves contributed to this reduction in mediated expressions of prejudice and we acknowledge that a myriad of social factors has contributed to this change. Nevertheless, the laws likely played a part in forming the climate within which newspapers are publishing fewer prejudicial letters.

Interviews with members of targeted communities also yielded insights into whether hate speech laws have exerted a positive influence on discourse. Indigenous interviewees tended to be pessimistic, stating that the prevalence of hate speech toward Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over time had remained the same, or increased. One interviewee said,

If you've got commentators who are out there with their hate speeches, a lot of it can be dressed up as acceptable speech, when, in actual fact, it's totally unacceptable. But, somewhere along the way, we've kind of been numbed into accepting that it's okay …

A common theme in the views expressed by interviewees was that hate speech remained a prevalent feature of life, but that its primary targets had changed. For example, a member of the Vietnamese community felt that things had improved (compared to the 1980s and 1990s) for Vietnamese people in Australia, but that racist attention had shifted to Muslims and more recent immigrant communities from Afghanistan and Africa. This view was echoed by Sudanese and Afghan interviewees. A Turkish interviewee said,

I think it shifts from community to community … so it might have been sixty, seventy years [ago] or whatever, the Italians and the Greeks, then the Middle Eastern [and] Turkish people, then it shifted to the Chinese, now to the … African and the Afghani community.

No interviewees thought that hate speech laws had had a profoundly positive influence on the quality of public discourse. However, a number were of the view that the laws had yielded some benefits:

Has legislation had an impact on the level of hate speech? I think it has to a certain extent. It doesn't mean it's eliminated it … But people are more conscious and aware of it … it has curtailed some of the utterances that people might hold back … So the legislation has had some role in perhaps reducing or minimising that harm.

One of the most positive assessments of the laws’ ability to prompt changes in public discourse came from Gary Burns, a Sydney campaigner who has pursued a number of homosexual vilification complaints under the New South Wales civil laws. Burns was strongly of the view that the publicity generated by litigation had improved the quality of public discourse regarding homosexuality. He regards his successful vilification complaint against high profile radio broadcaster, John Laws,Footnote 36 as a “breakthrough case” that set a precedent for the line between acceptable and unacceptable language in radio broadcasting and public discourse (Reference BurnsBurns 2013). These insights are consistent with our letters to the editor analysis, which showed stronger evidence of positive speech modification in relation to sexuality than in relation to race/ethnicity.

An Educative and Symbolic Effect?

The third, interconnected, question is the least tangible. Is there evidence from our study that Australian hate speech laws have had an educative effect on the public, or provide a symbol of support for targeted communities? We have already concluded that there have been two ways in which the laws play an educative role. The first is the direct and conscious use of prior judgments in community advocacy and as a device to curb ongoing vilification by telling the perpetrators that the court has stated that what they are doing is unlawful. One interviewee told us of a member of their community who had simply threatened a perpetrator with a complaint, and this was sufficient to stop vilification from recurring. A second, albeit less direct and harder to quantify, educative effect has been evidenced by the reduction in the proportion of prejudicial letters published in newspapers. Combined with the evidence of knowledge of the existence (if not the definition) of hate speech laws among letter writers, it is possible that the existence of hate speech laws has played a role in educating them in how to avoid confrontation with the laws, even if they still wish to express prejudice. Litigation may also have an educative effect, even where the conduct in question is ruled not to constitute unlawful hate speech. Burns stated in interview that, on at least one occasion he fully expected to “lose” an action he commenced (Reference BurnsBurns 2013).Footnote 37 For Burns, the litigation was worth pursuing because it afforded him an opportunity, including via associated media coverage, to promote debate about how homosexuality should (and should not) be portrayed on television.

However, it is also possible that even successful hate speech litigation can communicate messages that are at odds with the laws’ educational goals. Elsewhere (Reference Gelber and McNamaraGelber and McNamara 2013), we have analysed the public discourse that emerged in the aftermath of a hate speech decision of the Federal Court of Australia. That decision found that a popular conservative journalist, Andrew Bolt, and his employer Herald and Weekly Times had engaged in unlawful hate speech by naming fair-skinned Indigenous people, arguing that they had deliberately chosen an Indigenous identity over others that were more logically available to them, and that they had done so for personal gain. Bromberg J found that the journalist could not claim the good faith defense, because the impugned articles contained errors of fact, “distortions of the truth and inflammatory and provocative language.”Footnote 38 However, in the wake of the decision, Bolt launched an aggressive campaign to reconstruct what the decision stood for. This counter-narrative encouraged skepticism about the authenticity of fair-skinned Indigenous people and affirmed the validity of judgment by non-Indigenous people about the legitimacy of Indigenous identity according to skin color; questioned the legitimacy of Australia's hate speech laws; and strengthened a libertarian conception of free speech. The counter-narrative achieved powerful political traction, including endorsement by the then-in-opposition conservative Coalition in the national parliament. After being elected in late 2013, the governing Coalition released a bill seeking to amend federal hate speech law so as to protect virtually all public discourse from its ambit (Reference AbbottAbbott 2012; Reference BrandisBrandis 2014). This proposal was dropped in August 2014 following considerable public opposition (Canberra Times, August 7, Reference Richardson2014: 1, 4). Hate speech litigation and its outcomes can be appropriated to ends that are at odds with the law's educative purpose.

Importantly in interview many community members and representatives, when asked if they thought hate speech laws were important, expressed overwhelming support for their retention. There was a strong sense that the laws could make a positive contribution outside their formal utilization. The overwhelming view was that the laws were useful as a statement in support of vulnerable communities. Interviewees described it as important simply to “know they're there” and that they set a standard for what's “not acceptable.” Indigenous interviewees particularly recognised that hate speech could come from parliamentarians and the mainstream media, and saw Australia's hate speech laws as useful in setting a standard against which all people should be held to account. There is resonance here with Reference GouldGould's (2005) thesis about the impact of campus speech codes in the United States, which emphasises that they may have educative effects even in the absence of formal invocation or enforcement.

It follows that the legal form and parameters of hate speech laws may be less important than the fact of their existence. The Australian experience with civil hate speech laws suggests that a decision not to rely on the criminal law should not automatically be interpreted as a “weak” regulatory response, but rather as a potentially useful way of setting a standard for public debate.

A “Chilling Effect” or the Creation of Martyrs?

What of the fourth and fifth claims, that hate speech laws have a chilling effect, discouraging people from engaging in robust political debate on important matters of public policy, or that they create free speech martyrs who use the regulatory system to gain prominence for their views? Our analysis of letters to the editor revealed little evidence that public discourse has been diminished over the past 25 years. Robust debates have been had on a broad range of issues including the land rights of Indigenous Australians, same-sex marriage, and the treatment of asylum-seekers. Our analysis revealed the continued expression of prejudice over time. The fact that we detected a shift away from more intemperate styles of language cannot be said to support the chilling effect claim. At the heart of this claim is a concern about the silencing of views and opinion. At the same time that Bolt claimed he was being “silenced” by hate speech laws, he was able to disseminate his views widely through prominent media attention (Reference Gelber and McNamaraGelber and McNamara 2013: 474–76). Therefore, although the distinction may be contentious, we distinguish between desirable and undesirable effects. Hate speech laws are designed to influence the terms in which individuals express their views in public (desirable), however, they are not designed to make certain topics “off limits” (undesirable). Our research suggests that the risk of a chilling effect has not been substantiated. Australians are willing to express robust views on a broad range of policy issues.

The story of Bolt's encounter with federal racial hatred laws does lend some support to the claim that hate speech laws can produce martyrs. As noted, after Bolt was found to have breached federal racial hatred law, an orchestrated reconstruction of the decision dominated media discourse in which Bolt served as a representative victim for a wider class of opinion-holders on issues of Aboriginal identity, hate speech laws as incursions into free speech, and the vulnerability of free speech. These events confirm that the invocation of hate speech laws can have unintended effects that subvert rather than promote their underlying values.

Yet a sense of proportion is required here. No other case in over two decades of civil litigation has triggered a comparable martyr effect. Recalcitrant Holocaust denier Frederick Toben attempted to adopt a martyr position when he was found to have breached the same federal racial hatred law years earlier.Footnote 39 His refusal to abide by orders of the Federal Court to remove Holocaust denial material from his Web site resulted in 24 contempt of court findings and, ultimately, a 3 month jail term for contempt of court (Reference AkermanAkerman 2009). However, in public discourse this attempt served to consolidate his infamy and status as a powerful illustration of precisely why hate speech laws were enacted in the first place (Reference AstonAston 2014; Reference RichardsonRichardson 2014). Two distinctive features of Australia's hate speech laws are noteworthy here. First, given, that most transgressions of the law are addressed in confidential conciliation, with less than 2 percent resulting in court or tribunal decisions that enter the public domain, opportunities for martyrdom are rare. Second, because the laws rely overwhelmingly on civil remedies, they tend not to produce the criminal sanctions on which the claimed martyr effect is based. The Bolt controversy does not justify a general conclusion that hate speech laws necessarily produce a counterproductive martyr effect, as it was an atypical event in the history of civil hate speech laws in Australia.

Conclusions

Our project speaks both to the utility and the inefficacy of the regulatory model adopted by Australia 25-year ago. We have found that Australian hate speech laws provide some remedies. Members of targeted communities are able to lodge complaints with a human rights authority, in a process that reassures them that the law can assist them, and reminds them that the polity has enacted provisions that enable them to seek redress for hate speech. Further, the laws have a direct educative function. Although a very small proportion of cases reach a court or tribunal, those decisions that do enter the public domain have established important precedents that have been subsequently used in advocacy. The laws also have indirect educative value, both in terms of setting a standard for public debate and in the sense that (even unsuccessful) complaints can be used to raise awareness about appropriate ways of expressing oneself in public. Letter writers demonstrated an awareness of the existence of hate speech laws, and media entities have internalised the responsibility to educate their staff about those laws. There has been a significant reduction in the amount of prejudice expressed in published letters to the editor. We found no evidence of an undesirable chilling effect on public discourse, and considerable evidence that members of the public continue to express themselves on a range of controversial policy issues. We also found little evidence that Australia's regulatory framework produces an unwanted martyr effect, with only one case in the last 25 years having done so. Finally, targeted communities expressed overwhelming support for the value and retention of the laws, as a symbol of their protection and the government's opposition to discrimination.

In spite of these benefits, we found ongoing and significant levels of hate speech, a regulatory model that relies on individuals who are willing and able to bear the burden of enforcement, and an uneven distribution of benefits among targeted communities. We found that even in the mediated outlet of published letters to the editor, there has been an unsustained shift away from crude forms of language used to express prejudice toward Indigenous people, and no significant shift in the language used to express prejudice toward migrants, except in so far as the target changes with new waves of migration.

Our findings about the effects of hate speech laws in Australia produce valuable opportunities for further research that compares these results with countries and jurisdictions that have similar laws, do not have hate speech laws at all, or have them in different forms. The most obvious relevance of our findings is likely to be in those jurisdictions [e.g., several Canadian provinces (Reference McNamaraMcNamara 2005a, Reference McNamara2005b, Reference McNamara2007)] that have enacted similar civil laws. However, we assert that the insights presented here can also be applied more generally. In particular, our findings concerning the educative and symbolic value of the laws may be widely applicable, both in countries that have other regulatory models and countries that do not have such laws. The findings that there is no evidence of an undesirable chilling effect, and that the martyr effect is minimised in the Australian regulatory model, ought to be considered in relevant debates about the hypothesized effects of hate speech laws. The finding concerning unevenly distributed benefits should provide food for thought concerning the type of regulatory model being considered.

One might ask, of course, whether we are overstating our case for the utility of our findings. For example, it is possible that in other countries the appearance of crude epithets has reduced in mainstream newspapers, just as it has in Australia. One might argue that in other countries, expressions of prejudice continue to be a daily occurrence for many minority communities. One might argue that there are other ways of making targeted communities feel protected than enacting hate speech laws. If so, it would give advocates of hate speech laws significant pause since, if the same outcomes can be achieved without hate speech laws, what is their utility?

In response, we argue that we have identified outcomes that one would be unlikely to find in countries without hate speech laws, as well as outcomes that arise from Australia's particular regulatory model. The first is the deliberate use of previous judgments under the civil law as a tool in seeking to dissuade speakers from engaging in hate speech. The second is the use of the existence of the laws as a threat or inducement to hate speakers to desist. The third is the symbolic feeling of protection that hate speech laws of any type (whether criminal or civil, whether actively enforced/litigated or not) give to community members, and in spite of the persistence of significant levels of hate speech in society. Members of targeted communities told us that the laws had value even if individuals sometimes failed to live up to them. To these we would add that the laws have become an accepted part of the Australian political landscape. An April 2014 opinion poll showed 88 percent of the public supporting the retention of federal hate speech laws (ABC News 2014). This shows a very large majority of the public supports the idea that hate speech laws are an appropriate component of the framework within which public debate takes place. This gives them a normative influence, and provides participants in public debate with a language they can employ to condemn hate speech. These are the important benefits that have been achieved from 25 years of hate speech laws in Australia.