Without a doubt, a crucial development in judicial scholarship has been the increased interest in analyzing the lower federal appellate courts. Indeed, a convincing justification for scholarly attention to the U.S. Courts of Appeals is the well-known fact that the Supreme Court reviews relatively few courts of appeals decisions each year, thus leaving circuit court judges with the task of settling a number of important legal controversies (Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al. 2000:16–7). As Reference CrossCross (2007:2) notes, “The circuit courts resolve more than fifty thousand cases a year. Each of those decisions is binding precedent within the geographic bounds of the circuit and typically influences the application of the law even outside those bounds.” Unsurprisingly, he and several others claim these courts to be notable “policy makers” (see, e.g., Reference CrossCross 2007:2; Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2006:14; Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al. 2000:3), with the courts' contributions in this regard at least a partial function of their agendas (Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al. 2000:14–6) and a function of their role in handling issues prior to, or (in effect) in place of, adjudication by the Supreme Court (see, e.g., Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2006:15, discussing the pre-Grutter v. Bollinger [2003] importance of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals' decision in Hopwood v. State of Texas (1996) with respect to affirmative action; Reference KleinKlein 2002; Reference SegalSegal et al. 2005:230–3, discussing the importance of circuit court treatment of the military's “Don't Ask, Don't Tell” policy).

But while judicial scholars have acknowledged the contributions of circuit court judges in terms of their role as substantive policy makers in the U.S. legal system and, hence, have concentrated their efforts on investigating the nature of the courts' decisionmaking accordingly (see, e.g., Reference Humphries and SongerHumphries & Songer 1999; Reference Songer and DavisSonger & Davis 1990; Reference Songer and HaireSonger & Haire 1992), the contributions of circuit court judges to the development and implementation of threshold policies have not been systematically assessed (see Reference CrossCross 2007:186). Yet all federal court judges, including circuit judges, make important procedural decisions in the course of their decisionmaking, and these decisions have significant consequences for the litigants involved. Specifically, like all federal court judges, circuit judges have the ability to apply a number of threshold rules to reach or avoid reaching the merits of a given appeal. In addition, circuit judges are frequently asked to review the threshold decisions of lower court judges. These threshold or “access” decisions involve questions of standing to sue, mootness, ripeness, exhaustion, jurisdiction, and so forth. By granting or denying access to a full hearing on the merits, judges act as “gatekeepers,” regulating the judicial system's “demand input” (Reference Goldman and JahnigeGoldman & Jahnige 1971:114) and, thus, selecting those litigants and claims that will receive full judicial consideration (Reference Taggart and DeZeeTaggart & DeZee 1985:84).

Scholars have clearly demonstrated the importance of this type of procedural decisionmaking at the Supreme Court level (e.g., Reference Atkins, Taggart, Halpern and LambAtkins & Taggart 1982; Reference OrrenOrren 1976; Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen & Spaeth 1979, Reference Rathjen and Spaeth1983; Reference Silverstein and GinsbergSilverstein & Ginsberg 1987; Reference Taggart and DeZeeTaggart & DeZee 1985; Reference WasbyWasby 1976:31–54; Reference WasbyWasby 1984:121–44) and have examined standing decisions at the district court level (Reference Rowland and ToddRowland & Todd 1991) as well. However, the lack of attention toward procedural issues at the circuit court level has led to the portrayal of circuit judges as being relatively insignificant gatekeepers.Footnote 1 Although circuit judges do not have the gatekeeping capacity of the Supreme Court with its discretionary docket, nor are they as institutionally situated for this role as are federal district court judges (Reference Goldman and JahnigeGoldman & Jahnige 1971:114), circuit judges do consider threshold issues or access rules in a significant number of cases that are appealed to them each year (Reference CrossCross 2007:187).Footnote 2 Cases involving threshold rules thus present circuit judges with the opportunity to give effect to or constrain the discretionary gatekeeping decisions of lower court judges, and such rules, at least potentially, provide circuit judges with some leverage in reaching the merits of appeals.

And, in fact, given the sheer number of opinions involving the application of threshold issues by circuit judges relative to the Supreme Court, for example, one can see that circuit judges play a relatively important gatekeeping role. To get a basic idea of such trends, I examined the frequency with which threshold issues were considered in decisions reported in the U.S. Supreme Court Judicial DatabaseFootnote 3 and the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database,Footnote 4 the latter of which contains a sample of circuit court decisions. As seen in the former dataset, over the entire course of the Warren Court period, the Supreme Court considered at least one of these issues in 252 opinions while the Burger Court considered at least one of these issues in 297 opinions. In the time period between 1986 and 2000, the Rehnquist Court, moreover, issued 207 opinions involving these issues.

Such trends may be compared with those evidenced in the sample of circuit court cases found in the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database. For the Warren Court period, the appeals court database includes 733 circuit cases raising threshold issues and includes 1,219 cases for the Burger Court period. In the period of the (original) appeals court database covering the Rehnquist Court, moreover, there were 1,090 such cases.Footnote 5 Because the original appeals court database includes a sample of only 15 cases per circuit for the years prior to 1961 and only 30 cases per circuit from 1961 to 1996, the actual number of circuit opinions raising threshold issues in each of these periods is probably well above these figures. In addition, the appeals court database includes only published circuit opinions and thus likely underestimates the true prevalence of these decisions at the circuit court level. And, as noted above, as with respect to many other policy matters, most of these circuit threshold rulings are never reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The purpose of this article, therefore, is to take a closer look at the nature of these important decisions at the circuit court level. As suggested by previous research, the use and interpretation of threshold rules may be motivated by a number of goals, but, as the circuit court literature has demonstrated, institutional features surrounding courts of appeals decisionmaking can influence the nature of circuit judge decisions (see, e.g., Reference CrossCross 2007; Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2006; Reference KahenyKaheny et al. 2008) and thus are likely to play a role in the advancement of goals pertaining to procedural questions as well. Thus, for the purposes of the present study, I employ the theoretical framework of “new institutionalism,” which “focuses . . . on how institutions and larger structures dynamically shape the choices made in the political process” (Reference Gates, Gates and JohnsonGates 1991:477) to inform the development of a model of circuit judge gatekeeping decisions.

Specifically, while I explore the determinants of circuit court judge decisions to issue either flexible or restrictive threshold rulings, I pay particular attention toward the possible purposes that these rules may serve as well as key contextual features of circuit court decisionmaking that might influence their advancement. Indeed, while threshold rules may, in fact, offer circuit judges with potential discretion (see, e.g., Reference CrossCross 2007:180–1), the context in which such judges render threshold decisions will likely curtail the use of this discretion to serve policy goals—at least to some extent and, possibly, to a great extent. In addition, given the attention paid toward the role of litigant status and/or resources on a litigant's success on the merits in previous courts of appeals research (Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1992), it would seem particularly important to explore whether such characteristics might enhance one's opportunities for securing a pro-access vote at the circuit court level. Thus, I also consider circuit judge gatekeeping decisions in light of studies rooted in Reference GalanterGalanter's (1974) analysis of the “haves” versus the “have nots” in court.

Scholarly Investigations of Judicial Gatekeeping

As noted above, the use of various procedural or threshold rules to avoid reaching the merits of a given legal challenge might be conceptualized as a form of judicial gatekeeping. Although all federal court judges deal with these issues at all levels of the federal judiciary, attention in the literature has largely focused on the role of the federal district courts and the Supreme Court.

At the federal district court level, for example, scholars have suggested the importance of both judicial policy preferences as well as litigant status in one important area of access law: standing. Reference Rowland and ToddRowland and Todd (1991), for example, have found important differences in the tendencies of Presidents Richard M. Nixon/Gerald Ford,Footnote 6 Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan judicial appointees to grant standing to “upperdog” and “underdog” litigants. In particular, while the Reagan appointees exhibited more flexibility with respect to upperdog litigants, they were more inclined to restrict access to underdog litigants than were the appointees of Presidents Carter and Nixon/Ford (Reference Rowland and ToddRowland & Todd 1991:181).

Even more attention, however, has been focused on the procedural decisionmaking of the Supreme Court, with much of the scholarship comparing the access decisions of the Warren and Burger courts and/or the individual justices who sat on these courts. Key questions involved in this line of research have centered on the extent to which the Supreme Court has decided cases raising rules of access as well as the pro- or anti-access nature of those decisions (e.g., Reference Atkins, Taggart, Halpern and LambAtkins & Taggart 1982; Reference Taggart and DeZeeTaggart & DeZee 1985). Supreme Court scholars have also sought to identify the key variables driving the Court's access decisions. Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen and Spaeth's (1979:367) analysis of the Burger Court, for example, examines whether the Court's decisions in cases raising threshold rules were driven by “administrative/legal motivations,”“political considerations,” or an “overall orientation toward access per se.” Their cumulative scaling results suggest that each of these factors provided only partial explanations for the Court's access decisions, leading the scholars to investigate variation in the importance of these factors among the justices (Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen & Spaeth 1979:374).

Finally, Supreme Court scholars have analyzed the consequences of access decisions with respect to the merits of the cases in which they arise, hypothesizing that threshold decisions are related to judicial ideology. Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen and Spaeth (1983), for example, have examined Burger Court denials of access across the 1969–1976 terms. Their analysis suggests a strong connection between judicial votes on access and judicial ideology, finding that conservative justices have tended to deny access in cases when such denials produced conservative outcomes. Further, their examination of cases in which denials of access produced liberal outcomes is also consistent with their hypothesis.

While a number of studies document and explain this form of gatekeeping at the Supreme Court level, gatekeeping studies with a focus on circuit court decisionmaking have been far more limited in number. Nonetheless, a few legal scholars have explored circuit court access decisions and in doing so have shed light on the nature of these decisions in the circuit court environment. For example, in a case study of the D.C. Circuit's decision in International Labor Rights Education and Research Fund v. Bush (1992), Reference SmithSmith (1993:1615) argues that a circuit panel employed access rules “as a pretext” to sidestep a difficult decision. In his study of circuit court decisions to grant standing in environmental law cases, Reference PiercePierce (1999:1744), moreover, found that “Republican judges denied standing to environmental petitioners almost four times as often as did Democratic judges.” Thus, both of these circuit studies suggest that circuit judge decisions involving rules of access may be driven, at least partially, by a circuit judge's ideological preferences. Therefore, one can also infer that circuit court gatekeeping via the interpretation of access rules may be an important means by which circuit judges exercise discretion with respect to their mandatory dockets.

In a more recent effort, Reference CrossCross (2007:178–200) examines circuit court threshold decisions as part of his larger analysis of circuit judge decisionmaking. Relying upon the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database, Reference CrossCross (2007:188–9) investigates why a number of cases in which threshold issues were considered but access was denied were associated with conservative results and why those in which such issues were raised and access granted often had liberal results. The focus of his study, however, is not on individual circuit judge decisions on whether to grant or deny access in a given case. Rather, his analysis is largely focused on predicting liberal or conservative case outcomes.

Although these works contribute to the literature on circuit court gatekeeping, they do not provide an analysis of gatekeeping decisions in a fully integrated model. That is, while these studies suggest that circuit judge gatekeeping decisions may be utilized to advance such judges' policy goals, it is unclear whether other goals may also be in operation and whether their advancement may be influenced at all by the contextual features of circuit court decisionmaking. In addition, while litigant characteristics have been deemed important predictors in circuit judge merits decisions, despite the pretty serious implications of this being true with respect to threshold decisions, scholarship exploring differences among various litigants with respect to their ability to surpass procedural challenges has been noticeably absent. These issues, however, can and should be explored in the context of an integrated model of circuit judge gatekeeping decisions. The present study therefore attempts to fill this void in the circuit court literature by exploring the relative influence of attitudinal and legal forces as well as litigant characteristics in a model of circuit court gatekeeping, recognizing as well key institutional features of the circuit court context.

Theory and Hypotheses

Ideological Congruence

Circuit court studies indicate that circuit judges' policy goals play a contributory role in their decisionmaking processes (see, e.g., Reference Songer and GinnSonger & Ginn 2002; Reference Songer and GinnSonger, Ginn, et al. 2003; Reference Songer and HaireSonger & Haire 1992). As the literature on Supreme Court gatekeeping (e.g., Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen & Spaeth 1983) and the extant analyses of circuit court gatekeeping (e.g., Reference CrossCross 2007:178–200; Reference PiercePierce 1999; Reference SmithSmith 1993) suggest, procedural threshold decisions may also be explained, in part, by the judges' ideological preferences. That is, judges may be informed by the conservative or liberal implications of a particular ruling on a threshold issue and vote accordingly. Indeed, given the limited discretionary jurisdiction of the circuit courts, it would not be surprising if circuit judges turned to threshold doctrines to pursue their policy goals or construed them in a manner that conforms to their policy preferences. Access rules may also provide circuit judges with a means to keep certain categories of litigation or litigants off the judicial agenda.

One option in assessing the role of ideology in these decisions may be to assume that a liberal judge will tend to grant access to hearings on the merits, whereas a conservative judge will be inclined to deny such access. Indeed, using a measure of judge ideology as the sole independent variable in a model of circuit judge threshold votes to grant access suggests this very relationship (results not shown).Footnote 7 However, as noted above, Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen and Spaeth's (1983) Supreme Court analysis suggests that ideological influences may depend on the liberal or conservative outcome that an access vote may entail. Consequently, I suspect that liberal circuit court judges will be more flexible with respect to their access behavior when doing so will result in liberal outcomes, and conservative judges will be more inclined to issue pro-access decisions when doing so will produce conservative outcomes. If judicial policy preferences are driving access behavior at the circuit court level, then the presence of this type of ideological congruence should be positively related to the likelihood of a judge voting to open access. This suggests the following hypothesis:

H1: A circuit judge will be more likely to grant access when the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access vote is congruent with his or her ideological preferences.

Circuit Court Access Trends

The theory of new institutionalism, however, suggests the importance of institutions in influencing political behavior, including judicial behavior (e.g., Reference Gates, Gates and JohnsonGates 1991). Among Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth's (2002:93–6) noted reasons for the likely power of the attitudinal model in Supreme Court judicial decisionmaking is the Court's discretionary docket, its position atop the judicial hierarchy, and the fact that justices will generally not want to leave the bench for a more desirable position. Previous research on the substantive decisionmaking of circuit judges, however, suggests that the institutional characteristics of the circuit court context make it unlikely that ideological factors would play as strong of a role in circuit judge decisionmaking as they do in the Supreme Court context (Reference KahenyKaheny et al. 2008:499, citing Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 2002). Unlike their colleagues on the Supreme Court, circuit judges must be attentive to the norms and preferences of their circuit, and they face possible reversal by a higher tribunal. The lack of docket control, another key institutional feature of circuit court decisionmaking, also does not guarantee (politically) opportunistic decisionmaking with respect to the average threshold decisions that circuit judges confront.

Thus, as with circuit judge substantive decisions, it may be the case that the nature of the circuits' dockets or other institutional features of circuit court decisionmaking do not typically allow for the expression of circuit judge policy preferences with respect to most threshold questions. Again, because of the circuits' institutional position and, specifically, the types of cases circuit judges typically hear, the procedural questions raised in this context may be easily handled on the basis of existing precedent. In fact, deference to circuit court policy is especially likely given the importance of circuit court norms, including the norm of collegiality that fosters circuit consensus (Reference CoffinCoffin 1994:213–29). In addition, circuit court judges accord respect to the decisions of other panels in the circuit in an effort to achieve uniformity in circuit law (Reference HowardHoward 1981:210). These factors combine to suggest potential constraints on the expression of policy preferences in circuit judge gatekeeping decisions and thus suggest a second hypothesis:

H2: Circuit judges will be responsive to the pro-access trends of their respective circuits and will be more likely to grant access if their circuit exhibits a more flexible access policy.

Supreme Court Access Trends

In addition to the potential role of circuit court access policy, circuit judges might consider the policy trends of the Supreme Court. Indeed, the Supreme Court sits at the apex of the federal judiciary and at least theoretically governs access to the federal courts through its decisions relating to jurisdiction and justiciability (Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen & Spaeth 1979:360–1). Although the Court's rules in many of these areas have been criticized for being vague and applied in an inconsistent manner (see, e.g., Reference Cohen and VaratCohen & Varat 1997:81), the possibility remains that the Supreme Court's trends in granting access may serve as a constraint on lower court judge decisionmaking. Along these lines, circuit judges might look to the general policy trends of the Supreme Court prior to casting a threshold vote for guidance and, given the circuits' position in the judicial hierarchy, exhibit deference to the access policy of the Supreme Court. In addition, strategic-minded jurists might also exhibit deference to such trends in hopes of avoiding Supreme Court reversal. Both possibilities lead to the generation of a third hypothesis:

H3: Circuit judges will be responsive to the general pro-access policy announced by the Supreme Court and will be more likely to grant access if the Supreme Court issues a higher percentage of pro-access opinions.

Circuit Institutional and Strategic Concerns

In addition, institutional and strategic concerns may also influence circuit judge attention to both panel- and circuit-level preferences when a circuit judge is deciding whether to grant access in a given case. Of course, circuit judges do not operate alone; they typically make decisions in rotating three-judge panels and, hence, the nature of their decisions may be influenced by their desire to reach a consensual decision (see, e.g., Reference CoffinCoffin 1994:214). Thus, a given circuit judge may very well consider the policy preferences of the members of the panel on which he or she sits when deciding whether to cast a pro-access or anti-access vote. Similarly, although I note above the role of the Supreme Court as a possible source of reversal, given the very low rate of actual monitoring by the Supreme Court (Reference Songer, Gates and JohnsonSonger 1991:35), a circuit judge in an average case may be far more concerned with avoiding reversal by his or her circuit sitting en banc. Thus, panel- and circuit-level dynamics may increase the likelihood of individual circuit judges assessing the ideological congruence of a particular access decision with the preferences of their panel and/or circuit. These possibilities lead to the generation of two additional hypotheses:

H4: A circuit judge will be more likely to grant access when the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access vote is congruent with the preferences of the judge's panel.

H5: A circuit judge will be more likely to grant access when the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access vote is congruent with the preferences of the judge's circuit.

Litigant Status

Finally, the literature involving party capability theory, which highlights the importance of litigant resources and experience in achieving legal success, may also inform the present analysis. Indeed, Reference GalanterGalanter (1974:97) has persuasively outlined the advantages of “repeat players” as opposed to “one-shotters” in the judicial system. In addition to enjoying financial advantages and “ready access to specialists” (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974:98), repeat players, Reference GalanterGalanter (1974:98–103) argues, can engage the judicial system in a more strategic fashion in the legal challenges they choose to pursue. Such litigants may “play for rules in litigation itself,” a strategy that would not be a top priority for a one-shot litigant (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974:100).

Note that Galanter's framework has underpinned a number of studies examining the success rates of advantaged and disadvantaged litigants in the judicial system (e.g., Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1992; Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al. 2000:96–9; Reference WheelerWheeler et al. 1987). In their analysis of cases decided across three circuits in 1986, Reference Songer and SheehanSonger and Sheehan (1992) find that governments tend to be more successful than businesses while businesses retain advantages over individuals. The relative disadvantage of individual litigants is also clearly indicated in Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al.'s (2000) analysis of circuit decisions across 1925–1988. However, while most applications of what has become known as party capability theory have focused on litigant success on the merits, threshold decisions may also be a function of litigant characteristics and resources (see, e.g., Reference Rowland and ToddRowland & Todd 1991). Thus, in addition to a lower likelihood of achieving success on the merits, certain classes of litigants may face more difficulty than other classes in successfully meeting threshold requirements. Advantaged litigants (i.e., presumably those with better legal counsel and more litigation experience), for example, may be better prepared to successfully meet the legal challenges presented by threshold issues. Such decisions, moreover, may serve to reflect judicial biases with respect to certain litigant types.

Drawing from the party capability literature, therefore, I expect that government and business litigants will tend to be advantaged relative to individuals in the context of threshold disputes. Consequently, circuit judges should be more likely to grant access when a government entity or business is claiming access to sue in federal court. The relative advantages of groups and associations, however, are not as clear in these situations. On the one hand, groups with extensive litigation budgets and a geographically dispersed membership are likely in a better position to make strategic decisions as to which members (and even potential legal actions) might successfully pass threshold barriers. Moreover, such groups may also have more legal expertise to assist in the development of legal arguments pertaining to threshold issues that may arise in the litigation. On the other hand, groups and associations may also be more likely than the average individual claimant to bring litigation in hopes of changing institutional rules, including threshold doctrines, even if the group's chances of success in a given case are unlikely.

These two possibilities lead to the generation of the final hypotheses to be tested:

H6a: Parties typically disadvantaged in terms of their chances of winning on the merits (i.e., individuals) will face similar disadvantages in the context of threshold decisions. As a result, circuit judges will be more likely to grant access to advantaged (i.e., government entities and businesses) as opposed to disadvantaged litigants (i.e., individuals).

H6b: Circuit judges may be more or less likely to grant access to groups or associations relative to traditionally disadvantaged litigants (i.e., individuals).

Data and Methods

The circuit judge voting data used to test these hypotheses are derived from the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database. Specifically, the threshold votes modeled in this analysis are those cast by circuit judges in regular panel decisions in the years 1958–1996.Footnote 8 The background data on circuit court judges are derived from the Multi-User Database on the Attributes of United States Appeals Court Judges (hereafter, Auburn Database),Footnote 9 with updated material drawn from the Federal Judges Biographical Database.Footnote 10

In order to analyze individual judge votes on access, I transformed the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database so that individual circuit judge votes are the units of analysis. As a result, the database includes a judge's vote on the liberal or conservative outcome of a given issue raised in the caseFootnote 11 (e.g., civil liberties/rights, economic, etc.) as well as the judge's vote on the threshold issue (e.g., pro-access or anti-access) if a threshold issue was considered. Although the database codes for the liberal or conservative direction of each individual judge's vote on the substantive issue raised in a given case, the database does not include individual judge decisions with respect to the threshold issues raised in a case (e.g., individual judge decisions on whether to grant or deny standing, individual judge decisions as to whether the circuit or lower court has jurisdiction, etc.). Instead, the database is constructed so that only the position of the majority outcome (i.e., whether the majority issued a pro-access or anti-access decision) is coded with respect to threshold issues. This raised no concern in cases in which there was no registered dissent; each participating judge's vote on the threshold issue is the same as that registered for the panel majority. However, a small number of circuit decisions included dissents, and it is possible that a circuit judge would dissent on the procedural issue raised in the case as opposed to the substantive issue. Therefore, I identified those judges who dissented in the sample of access cases analyzed in the present study and read their dissenting opinion in order to determine if the judge dissented on the merits or on the threshold issue. If the judge dissented on the procedural question, I recoded the individual vote on the threshold issue accordingly. Consequently, the dataset employed in this analysis includes individual judge decisions to grant or deny access when a threshold issue was raised in a case and also indicates whether those decisions were affiliated with liberal or conservative outcomes.

The dependent variable in the models presented below is the individual judge's vote on the threshold question, coded 1 if the vote was “pro-access” and 0 if the vote was best conceptualized as an “anti-access” decision. Specifically, threshold decisions in which the circuit judge concluded that the district court properly reached or should reach the merits or in which the circuit judge agreed to reach the merits of the appeal (in the event of a threshold question raised at the appellate level) were considered as “grants of access” and were coded as 1. Outcomes in which the circuit judge held, on the basis of at least one threshold rule, that the district court properly avoided the merits or should have avoided the merits, or in which the circuit judge found that the merits of an appeal should not be reached, were coded as 0 and were considered to be “denials of access.”Footnote 12 Examples of pro-access decisions would include those where a circuit judge ruled that the appeals court had jurisdiction to reach the merits of an appeal or that a litigant should have been granted standing to sue before the district court. Opposite outcomes in these sorts of situations would be examples of anti-access decisions.Footnote 13

Previous studies on the Supreme Court indicate the possibility that the nature of pro-access decisions may vary across the type of procedural issue being raised (e.g., Reference Taggart and DeZeeTaggart & DeZee 1985). In particular, previous work has examined Supreme Court threshold decisions across two or three major categories of access, including proper party questions, proper forum questions, and jurisdictional questions. Using previous work as a point of departure, I examined the model developed here across all threshold issues coded in the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database (i.e., jurisdiction, statement of a proper claim, standing, mootness, exhaustion, ripeness, timeliness, immunity, frivolous suit, political question, and the miscellaneous threshold categories) and separately for proper party and proper forum votes. For the purposes of this study, proper party votes are operationalized to include decisions on standing, ripeness, and mootness, as well as the timeliness of the litigation or appeal (including filing fee matters or questions involving a statute of limitations) and whether the plaintiff stated a proper claim.Footnote 14 Proper forum votes, on the other hand, include votes on jurisdiction, exhaustion of remedies, immunity of the defendant, or the applicability of the political question doctrine. The decision to examine jurisdictional questions as part of a category of proper forum cases as opposed to a separate category is distinct from previous work on the Supreme Court level. Due to the nature of the sample of circuit court cases available for this study, however, a separate analysis of jurisdictional votes would not be particularly useful. Moreover, insofar as typical jurisdictional issues question the ultimate authority of the court to issue a decision, it is quite reasonable to assume these questions under the larger category of proper forum votes. Otherwise, attempts were made to conform the above categories to previous work (see Reference Taggart and DeZeeTaggart & DeZee 1985).

Independent Variables

Judicial Ideology

Of great interest in the present study is the proposition that circuit judges might be more likely to grant access when the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access vote corresponds with the judge's own ideological preferences. The test of this hypothesis requires the development of a measure of ideological congruence and, thus, a measure of judicial ideology. For the purpose of measuring individual circuit judge ideology, I relied upon the common space NOMINATE score of the judge's appointing president (see Reference PoolePoole 1998), assuming that presidents typically appoint judges who will reflect their own ideological preferences (e.g., Reference Songer and GinnSonger & Ginn 2002). I then linked these scores with the substantive ideological outcome of the access vote to measure the degree of ideological congruence. Given that larger and more positive NOMINATE scores are associated with conservative presidents (and, thus, conservative circuit judges) while negative and smaller scores are associated with liberal presidents (and liberal circuit judges), if the ideological outcome of a pro-access vote and the judge's ideology might be perceived as liberal (i.e., the appointing president's NOMINATE score was negative), then the congruence term took on the value of −1*(judge ideology), thus producing a positive value on the congruence term. If pro-access votes resulting in conservative outcomes were cast by liberal judges, then this would be evidence of a lack of ideological congruence with the vote, and, hence, the congruence term would take on the value of the appointing president's (negatively signed) NOMINATE score. I took a similar approach with respect to other combinations of access votes, such that the more congruent a judge's ideology was with that of the outcome of the access vote, the larger (and more positive) the congruence term. Consequently, I expected a positive relationship between this variable and the likelihood of a pro-access vote.

Circuit Court and Supreme Court Access Policy

As noted above, however, it is unclear whether the nature of the decisions in which threshold questions arise and/or the institutional characteristics of the circuit court context will afford opportunities for judges to exercise much policy discretion with respect to procedural questions of access. Thus, of theoretical interest in this area is the potential influence of circuit court and Supreme Court access law. To develop a measure of circuit court access law, I used the sample data available in the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database to calculate a three-year moving average of the percentage of cases in which the circuit, either sitting in panels or en banc, decided to grant access to a litigant for a hearing on the merits of his or her underlying dispute. As in the coding of the dependent variable, a pro-access decision occurred when the circuit court sustained a district judge's decision to reach the merits or directed the district court judge to reach the merits, or in which the circuit agreed to reach the merits of an appeal despite a potential threshold bar. In the event that a circuit did not consider threshold issues in a given sample year, I used the percentage of pro-judicial power decisions in the previous year of available sample data to compute this measure of legal precedent. This approach was justified insofar as precedent remains in force until it is modified or overturned by a subsequent decision. For the pooled model of all threshold votes, this measure of circuit law included all judicial power issues raised in the sample of cases (e.g., jurisdiction, statement of a proper claim, standing, mootness, ripeness, timeliness, exhaustion, immunity, political question, frivolous suit, and miscellaneous threshold issue). This measure of legal policy, however, was restricted to the percentage of circuit court pro-access proper party decisions in the proper party model and circuit court pro-access proper forum decisions in the proper forum model.

Measures for Supreme Court access policy were developed in a similar manner. Here, I relied on the “judicial power” cases coded in the U.S. Supreme Court Judicial Database (see Supreme Court Database Codebook, pp. 51–3; The United States Supreme Court Judicial Database 1953–1999 Terms, Harold J. Spaeth (Principal Investigator), NSF# SES-8313773 and SES-8812935. The database and documentation (codebook) are available at the Web site of the Judicial Research Initiative (JuRI) at the University of South Carolina, http://www.cas.sc.edu/poli/juri/). Such cases involve issues of comity, review of agency action, mootness, timeliness, venue, standing, jurisdiction, collateral estoppel, etc., and, hence, are those cases in which the Supreme Court formulates its access policy. As with the circuit measure, in the model of all circuit threshold decisions, the measure of Supreme Court access law was a three-year moving average of the percentage of cases in which the Court extended the use of the judicial power (i.e., decided a case in a pro-access manner).Footnote 15

For the models of proper party and proper forum votes, I matched the categories or types of judicial power cases in the Supreme Court judicial database as closely as possible to the proper party and proper forum categories of circuit votes designated for this study and computed separate Supreme Court legal measures for the two doctrinal areas. Again, however, there were instances in which the Supreme Court did not render judicial power decisions in these more narrow categories in a given year for the purposes of calculating three-year moving averages. Therefore, as with the circuit law measures, the measure of Supreme Court law in the models of proper party and proper forum votes was a moving average of the percentage of pro-judicial power decisions in these doctrinal areas in the past three years of available data, resting again on the assumption that the Supreme Court's precedent remains in force until later modified or overturned. I expected all legal policy variables to be positively related to the dependent variables in each of the models.

Finally, as noted above, some of the same institutional features of the circuit court context that justify the test of legal influences on circuit judge access decisions warranted the specification of other panel and circuit-level variables. In particular, it is possible that a circuit judge will defer to the ideological tendencies of the panel on which the judge sits in a given case or with respect to his or her larger circuit when making threshold decisions.

To account for the potential influence of the panel, I included an ideological congruence measure that sought to tap the extent to which a circuit judge's decision to cast a pro-access vote was congruent with the median panel member's ideology. To measure the median panel member's ideology, I utilized the common space NOMINATE score of the president who appointed the median judge on the panel. If the ideological outcome of a pro-access vote was liberal and the median judge might be perceived as liberal (i.e., the appointing president's NOMINATE score was negative), then the congruence term took on the value of −1*(judge ideology), thus producing a positive value on the congruence term. If liberal pro-access votes were cast by those participating on a panel with a conservative panel median, then this would be evidence of a lack of ideological congruence with the median member and, hence, the congruence term would take on the value of a negatively transformed NOMINATE score of the president who appointed the median member. I took a similar approach with respect to access votes that entailed conservative outcomes, such that if judges considered the likely ideological position of the panel median, the larger (and more positive) the congruence term. Of course, the same method can be applied to determine whether a judge's access votes were congruent or incongruent with the ideological tendency of the circuit (i.e., the circuit median); hence, I also included a variable tapping the ideological congruence of a pro-access vote with the preferences of the circuit median. Again, I employed the common space NOMINATE score of the president who appointed the median judge on the circuit for this purpose. I expected a positive relationship with respect to both variables if panel and circuit ideological centers were influencing individual circuit judge decisions to cast a pro-access vote.

Finally, the role of litigant status and resources in threshold decisionmaking were captured with the inclusion of three dummy variables denoting whether the party claiming access to the federal courts was an “interest group or association,”“business,” or “governmental entity.”“Individuals” were selected as the base or excluded category.Footnote 16 The use of litigant categories as an indirect method by which to assess litigant resources is consistent with the practice of previous studies of party capability theory (e.g., Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1992; Reference WheelerWheeler et al. 1987). Following these studies, I assumed that governments would typically be advantaged relative to businesses and individuals, and that individual litigants would tend to be disadvantaged relative to both governments and businesses. As noted above, it is not readily apparent whether groups and associations would be advantaged or disadvantaged compared to the other litigant types in the context of threshold decisions. However, rather than exclude a potentially important variable, I included a dummy variable assessing whether a group or association was claiming access to the federal courts but did not specify a direction with respect to the coefficient of this variable.

Control Variables

Caseload

Thus far, I have considered the potential influences of legal and ideological factors as well as litigant characteristics in understanding the nature of circuit court access decisions. One other possibility, of course, is that such decisions are a function of institutional concerns or goals. Indeed, it is important to note that many of these threshold rules were developed, at least in part, out of the desire to preserve judicial resources (Reference MurphyMurphy et al. 2002:239). Thus, the desire to preserve judicial resources may result in circuit judges denying hearings to the merits of appeals or in affirming lower court decisions that deny this type of access.

While at least one study of Supreme Court decisionmaking has examined whether access decisions are a function of administrative concerns (Reference Rathjen and SpaethRathjen & Spaeth 1979), little is known as to whether administrative concerns and, in particular, caseload pressures, may influence circuit court access decisions. Yet there are reasons to believe that these pressures could play a major role in circuit court gatekeeping practices. The documented growth in the number of case filings in the circuit courts (see, e.g., Reference Songer and SheehanSonger, Sheehan, et al. 2000:14–6) may very well translate into the more restrictive use of gatekeeping rules. Unlike the proposition that threshold decisions may be used to advance a judge's policy goals in a given case, the idea that judges may employ such rules to control case volume would be a more long-term goal of the circuit courts. Nonetheless, it is quite possible that circuit judges may resist granting access to litigants because doing so may open the floodgates and result in an even larger caseload. If a growing caseload and understaffed work environment are encouraging circuit judges to curb access to the courts, one should see a negative relationship between increases in a circuit judge's caseload and the likelihood of a judge casting a pro-access vote. Thus, I included a control measure for the circuit's caseload, utilizing the number of appeals commenced in the circuit per active circuit judge. The measure was lagged one year.Footnote 17

Lower Court Decision

A new institutional framework for assessing decisionmaking in this area should also consider a circuit judge's institutional position relative to the lower court whose decisions such judge reviews. As intermediate appellate courts, circuit judges review the decisions of district courts or administrative agencies, and the nature of these lower court or agency decisions may influence the actions taken at the circuit level. As former First Circuit judge Frank Reference CoffinCoffin (1994:260) describes, appellate court judges may exhibit deference toward the decisions of lower court judges. Moreover, the lack of broad discretion to pick and choose the cases they review means that circuit judges will hear many appeals in which they will simply uphold the lower court decision, as that decision likely represents a straightforward application of precedent (Reference Songer and GinnSonger & Ginn 2002:312). In particular, since these gatekeeping inquiries may ultimately lead to the dismissal of a case rather than a decision on the merits, circuit judges may be more likely to find a threshold problem on appeal if the lower court originally hearing the dispute dismissed the legal challenge. The norm of lower court deference may also result in a circuit judge agreeing with the lower court judge's gatekeeping decision if the lower court judge also ended up dismissing the case. Consequently, I included a control variable, “lower court dismissal,” coded 1 if the lower court originally dismissed the case and 0 otherwise.Footnote 18 This variable should be negatively associated with a given circuit judge's tendency to grant access.

Given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable (i.e., the individual judge's decision to vote to grant or deny access), I tested the hypotheses discussed above in a series of logistic regression models. Specifically, I tested the models across a pooled category of circuit judge threshold votes cast across most substantive issue areas of the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database in the time period 1958–1996.Footnote 19 The analysis was limited, however, to threshold votes cast in panel decisions due to the potential influence of contextual differences between panel and en banc decisionmaking environments (e.g., Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2003:800, citing Reference GeorgeGeorge 1999). Finally, since each sample contained multiple votes cast by individual judges, I treated any single judge's votes as nonindependent and, therefore, reported robust standard errors clustered on the individual judges.

Before turning to the results, it is important to note that the sample of cases coded in the U.S. Courts of Appeals Database includes only votes cast in published circuit decisions. Consequently, one's ability to generalize beyond these types of cases is necessarily limited. This is a particularly important issue given that a number of gatekeeping decisions are likely to be made in circuit cases decided without a published decision. However, analyzing threshold decisions in the context of published cases is also of great interest. If published decisions are generally those that are more likely to affect the legal policy of the circuit (e.g., Reference Songer and SheehanSonger et al. 2000:10), the present analysis should help in the assessment of the extent to which the variables identified above contribute to the development of circuit court access policy, policy that becomes very important given the rate of review of the Supreme Court.

Results

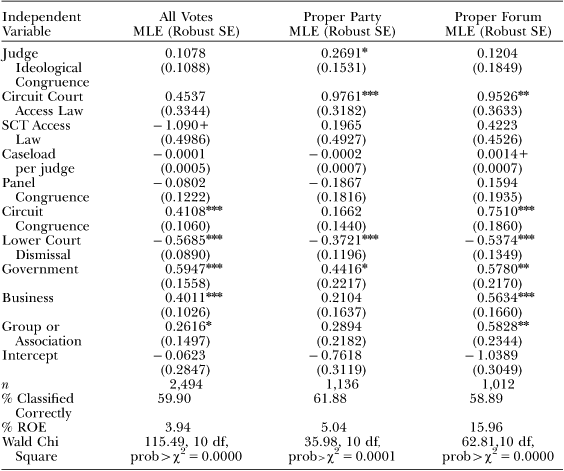

The results of the model of circuit court threshold decisions across all types of threshold questions (including votes on proper party and forum issues, inquiries concerning whether the case or appeal were frivolous, and those that fell into the database's miscellaneous threshold issue category) and separately for proper party and proper forum questions are found in Table 1.

Table 1. A Model of the Likelihood of a Pro-Access Vote

* p<0.05,

** p<0.01,

*** p≤0.001

+ Significant, but sign of coefficient is opposite to that hypothesized (p≤0.01)

Note: All tests are one-tailed, with the exception of the group/association variable, which is two-tailed.

As seen in the table, circuit court gatekeeping decisions are best described as a function of legal and extralegal factors, including judicial attitudes, circuit court law, circuit court ideology, the nature of the lower court decision, and litigant characteristics. However, the portrait of circuit judge gatekeeping decisions presented here suggests that while some factors are influential across the board, other factors may vary across the type of threshold question being considered.

One of the more striking findings in the table is the apparent influence of circuit court law. While the variable failed to reach significance in the pooled model of all threshold votes, it did reach significance when more refined measures of circuit legal trends were employed in the models of proper party votes and proper forum votes. Circuit court law, therefore, appears to be a reliable guide for circuit court judges when they are casting threshold decisions.

Another interesting finding relates to the role of individual judge ideology as well as circuit court ideology. As noted in the table, the coefficient on the judge ideological congruence variable was positive and statistically significant in the model of proper party votes (i.e., votes on standing, mootness, timeliness, and statement of a proper claim). This suggests that circuit judges are more likely to grant access to a full hearing on the merits when the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access proper party vote is consistent with the judge's own ideological preferences. In these cases, however, the ideological preferences of the circuit median played no role in influencing individual circuit judge decisions on access. On the other hand, in the model of proper forum votes (i.e., votes on jurisdiction, exhaustion of remedies, immunity of the defendant, or the applicability of the political question doctrine), circuit judges did tend to take note of the circuit's ideological center, but their votes to open or close the door to a hearing on the merits did not appear to be contingent on their own individual preferences. Some possibilities here are that proper party questions relate to issues that simply generate greater ideological voting or that the associated proper party access doctrines provide more leverage for judges to implement their policy preferences than the proper forum doctrines.

Note that the study also provides clear support for the idea that litigant status can influence circuit judge gatekeeping decisions. In all three models, governments seeking access were more successful than individual litigants. Business litigants, moreover, were more successful than individuals in securing pro-access decisions in the pooled model of all threshold votes and, more specifically, in the model of proper forum votes. Groups and associations enjoyed similar advantages over individual litigants. Interestingly, however, neither businesses nor groups enjoyed advantages over individuals in obtaining pro-access decisions when the circuit judges were considering proper party questions (e.g., standing, mootness, ripeness, and timeliness).

In addition, as expected, the type of lower court action taken in a given case appeared to influence a circuit judge's decision in allowing a hearing on the merits. As hypothesized, the “lower court dismissal” dummy variable was negatively signed and statistically significant in the three samples of threshold votes, indicating that circuit judges are generally less likely to grant access to a full hearing on the merits of an appeal and are more likely to sustain a lower court's decision to deny access when the lower court dismissed the case.

The table also reveals some potentially optimistic news from the vantage point of litigants seeking access to the federal judiciary. Namely, caseload pressures were not associated to a statistically significant degree with a lower likelihood of gaining access for the purposes of obtaining a full hearing on the merits. In fact, in the model of proper forum votes, the coefficient on the caseload variable was positively signed and reached statistical significance in the positive direction. Therefore, rather than responding to an increasing caseload by curbing access, circuit judges are likely finding more opportunities to grant litigant access as the number of cases increases, at least in the context of these published decisions. One possibility, of course, is that the administrative and more long-term goal of guarding judicial resources is offset by other perceived judicial goals. Indeed, as Judge Reference CoffinCoffin (1994:257) notes, “A judge may be deeply concerned over the danger of overburdening the courts and may take a restrictive view on allowing access to them or may be just as deeply concerned about the denial of such access by rulings that appear to be overtechnical.”

However, there are a few curious results that emerge in Table 1. One interesting finding was the lack of a relationship between the panel's ideology and individual circuit judge votes on access. While I hypothesized that circuit judges would be more likely to grant access if the outcome of such a decision was congruent with the panel median's ideological preferences, the results suggested no such relationship in any of the models. In addition, in the pooled model of threshold votes, increases in the number of opinions in which the Supreme Court extended the use of the judicial power in the previous three years were associated with a lower likelihood of a circuit judge voting to grant access. This relationship was opposite to that hypothesized. However, when utilizing more refined measures of Supreme Court access doctrine in the models of circuit judge proper party and proper forum votes, the results indicated a lack of a relationship between the policy trends of the Supreme Court and the likelihood of a pro-access circuit judge vote. While the apparent relationship in the first model may be a function of an overly broad measure of access policy, the lack of a relationship in the models that utilized more refined measures of the Supreme Court's legal policy is not terribly surprising. Given the Supreme Court's low rate of review of circuit decisions, circuit court judges may make greater efforts to ensure that their decisions are in line with both circuit court access policy and the circuit's median member, and the findings appear to give credence to this proposition.

To provide further aid in interpreting the results of the logistic regression models, I examined the relative influence of those variables reaching statistical significance in the models of proper party and proper forum votes. For the purposes of this analysis, I computed changes in the estimated probabilities of a pro-access vote for individuals (the modal category of litigant) facing a threshold challenge in a case that was not dismissed by the lower court. As seen in Table 2a, as the value of the judge ideological congruence variable was altered from its minimum to its maximum value (i.e., from least to most congruent with the substantive ideological outcome of a pro-access vote), the probability of a pro-access proper party vote increased by about 0.07. Moreover, there was a 0.24 difference in the probability of a pro-access proper party vote when the circuit law measure was altered from its lowest to highest value (from a circuit with the most restrictive access policy to that with the most flexible access policy). The table also indicates that circuit court legal policy exerted a similar influence in proper forum votes. In the proper forum context, however, its influence was rivaled by that of the ideological preferences of the circuit court median.

Table 2a. Change in the Predicted Probability of a Pro-Access Vote, Individual Seeking Access*

* Independent variables are altered from their minimum to maximum values, holding continuous variables constant at their mean values and lower court dismissal at its modal value (i.e., not dismissed).

In addition, Table 2a examines the change in the probability of an individual receiving a pro-access vote across situations in which the lower court did not dismiss the case as opposed to those in which it did, holding the other variables in the model constant at their mean values. Here, the difference in the probability of a judge granting access to an individual litigant across these two situations was −0.09 in the model of proper party votes and −0.13 in the model of proper forum votes.

Table 2b, moreover, is helpful in illustrating the role of litigant status in circuit judge threshold decisions. Holding all other variables constant at their means and assuming the lower court did not dismiss the case, the probability of a judge casting a pro-access proper party vote for a government litigant was 0.53, while the probability of an individual litigant receiving a pro-access vote was only 0.42. Unsurprisingly, the relative advantage of business and group litigants fell in between these two extremes in the model of proper party votes. In proper forum decisions, on the other hand, governments, businesses, and groups seemed to be equally advantaged over individuals. Whereas individuals facing a proper forum challenge had a 0.48 probability of receiving a pro-access vote, governments, businesses, and groups had a 0.62 probability of receiving a pro-access vote, holding other variables constant. Across both threshold categories, the results thus suggest a clear disadvantage for individuals when they confront threshold challenges in circuit court litigation.

Table 2b. Estimated Probability of a Pro-Access Vote

* Predicted probabilities computed holding all continuous variables at their mean values and lower court dismissal at its modal value (i.e., not dismissed).

Discussion

Although one might reasonably associate the notion of judicial gatekeeping with federal district court judges who are in an obvious position to regulate access to the federal courts or the Supreme Court, with its largely discretionary docket (Reference Goldman and JahnigeGoldman & Jahnige 1971:114), the present study suggests that circuit judges also play an important gatekeeping role in the federal judicial system. Namely, circuit court judges review the gatekeeping decisions of lower court judges and also decide whether the merits of an appeal should be reached. Moreover, given that the Supreme Court reviews relatively few circuit decisions each year, circuit decisions as to whether a litigant should be allowed to proceed in federal court or whether a certain legal claim should be reached are often final. Thus, it is of great importance that judicial scholars investigate the nature of these decisions in order to determine whether threshold rules do, in fact, provide an important source of discretion for circuit court judges.

At the circuit level, however, the ability to either apply or interpret threshold rules as a means of furthering a judge's policy preferences, to favor a particular type of litigant, or to further some other purpose or goal (e.g., to influence the nature and volume of judicial agendas) could theoretically be limited by the institutional context in which circuit judges render their decisions. Previous research on circuit court decisionmaking beyond the gatekeeping context is certainly suggestive, moreover, that multiple factors or variables serve to influence the nature of these judges' decisions. A new institutional perspective in investigating the nature of circuit judge threshold decisions thus seems particularly appropriate. As Reference Brace and HallBrace and Hall (1993:916-17) suggest, “From this perspective, decisions are not merely the collective expression of individual preferences, the result of the simple application of legal rules or the reflection of structural characteristics of institutions. Instead, judicial decisions are the result of a complex interaction of preferences, rules, and structures.”

Thus, in this study, I developed a model of circuit court threshold decisionmaking that was sensitive to the institutional context of the courts of appeals and, specifically, sought to tap the possibility that circuit judge threshold decisions might be a function of both legal and extralegal variables. Specifically, the model was applied across all threshold decisions in the sample (proper party, proper forum, frivolous, and miscellaneous threshold issues) and in more limited samples of proper party and proper forum votes. The results suggest that circuit court gatekeeping is, indeed, a function of multiple factors, including circuit court law, litigant status, the lower court decision and at times the ideological preferences of the circuit judge or that of his or her circuit.

The apparent link between judge ideology and access votes in the circuit judges' proper party decisions suggests an important source of judicial discretion operating at this level of the federal judiciary. However, this discretion appears tempered by circuit legal policy. While individual judge ideology influenced circuit judge proper party decisions, the judge ideology congruence term did not reach significance in the model of proper forum decisions. Circuit pro-access trends, on the other hand, were positively associated with individual judge decisions to grant access across both of these threshold areas. Moreover, at least in the proper forum context, the results suggest that circuit judges may be considering the ideological center of their circuit when considering how to vote on threshold questions.

Another important finding of the study, however, involves the clear advantage seen for government litigants when confronting threshold challenges as opposed to the clear disadvantage encountered by individual litigants. Indeed, such results were evident in the pooled model of all threshold votes as well as in the separate model of proper party votes. In the proper forum model, moreover, government, business, and group litigants were all more successful than individuals in securing pro-access votes. To date, the empirical focus of party capability analyses at the circuit court level has been on litigant success on the merits of legal claims. The present study suggests the importance of litigant resources or status at an even more critical stage of the decisionmaking process.