By many measures, the Chinese family law is exemplary in its provision of protections for women. The principle of gender equality is enshrined in the Chinese Constitution. A law passed by the National People's Congress in 1992, the “Women's and Children's Rights Protection Law,” provides women facing divorce with a range of specific protections. More recently, as a response to the emerging problems faced by women in the now market-oriented China, the 2001 amendment of the Marriage Law penalizes spouses who have committed bigamy, illegal cohabitation, family violence, or desertion (Art. 46). While this article is gender neutral in its wording, it is clearly motivated by the goal of protecting women.

How do these well-meaning laws fare in practice in a traditionally patriarchal country like China? Equal protection of the sexes, a slogan of the Communist Party since it came to power, certainly runs counter to China's traditional values. How does this dissonance between legal rule and social reality play out? Does it mean that the law, at least in the civil sphere, can effectuate some important social changes? Or are the courts, even in an authoritarian state such as China, in fact more limited in their ability to facilitate social reform in the absence of a strong, society-wide belief in gender equality?

Legal Discourse and Gender Equality

This study explores the interplay between family law and gender (in)equality by examining courtroom discourse in China. It is well accepted among scholars of law and society that the actual discourse of law goes beyond the narrow confines of black-letter law. In court, judges, lawyers, and litigants alike argue, persuade, and justify by deploying rhetoric that reflects the sentiments and values of a social world of which the law is just a part. While this has been taken for granted in the law and society scholarship, little effort has yet been made to explore precisely how notions of rights, entitlements, responsibilities, and moralities are invoked by legal actors in courtroom proceedings in China. If language is indeed power (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1987; Reference Conley and O'BarrConley & O'Barr 2005; Reference FoucaultFoucault 1972, Reference Foucault and Foucault1980), it is plainly impossible to arrive at an understanding of how legal power is deployed and contested without looking into live discourses where the control of meaning is fought over.

This article attempts to fill this gap by investigating the ways judges negotiate the contested meanings of divorce with litigants in China. Our study builds upon a growing literature in the field of law and society that takes legal discourse as a form of institutional discourse that expresses as well as constitutes social division and inequalities (Reference HirschHirsch 1998; Reference MatoesianMatoesian 2001; Reference MerryMerry 1990; Reference MertzMertz 2007; Reference NgNg 2009; Reference RichlandRichland 2008; Reference TrinchTrinch 2003). Legal discourse is most powerful in imposing a frame of reference that structures expressions of conflict (Reference FelstinerFelstiner et al. 1980–1981; Reference Mather and YngvessonMather & Yngvesson 1980–1981; Reference MerryMerry 1990). It is therefore a domain where social interests and power relations are reproduced as well as contested (Reference FoucaultFoucault 1972, Reference Foucault and Foucault1980).

As a case study of the rapidly developing norms in Chinese courtroom discourse, this article makes an academic contribution on three levels. By analyzing courtroom dialogs in actual trials, we reveal an emergent “pragmatic discourse” that is increasingly being deployed by judges during the process of in-trial judicial mediation. Through deliberate and repeated deployments of this new pragmatic discourse, judges turn divorce court trials into a forum where specific official understandings of women's welfare take priority. In addition, this study uncovers the ways in which judicial mediation masks the assertion of power over litigants despite its ideological claims to the contrary. Through questions, statements, rebuttals, and other interactional devices, Chinese judges define the premises that underpin the law's understanding of gender equality and women's welfare. They thus exercise power over litigants, subtly and interactionally, through the use of language (Reference PhilipsPhilips 1998). It is in this sense that legal power is discursive, very much in the Foucauldian sense: that is, legal discourse systematically forms the objects of which it speaks (1972: 49).

Finally, we seek to understand how formally gender-neutral legal orders nonetheless reinforce the gender hierarchy. By looking at how discourses are deployed in situ, we also show how judicial mediation as an institutional procedure reinforces the gender hierarchy despite its formal commitment to promoting gender equality (see Reference CollierCollier 1988; Reference EhrlichEhrlich 1998; Reference HirschHirsch 1998). Despite their efforts to protect women's rights, judges often inadvertently reinforce and perpetuate the patriarchal norms and values that render women the passive recipients of the consequences of marital breakdown. As we will show, the effect of this pragmatic discourse is particularly damaging for those women who are economically and socially most vulnerable.

Besides our aim to demonstrate the theoretical significance of live courtroom discourse in the dispersal of legal power, we also explored the social landscape of a rapidly changing China. Divorce has quickly become a major category of civil trials in most of urban China, making up 23% of all civil and commercial cases in 2010 (China Law Yearbook 2011: 171). Designated family courts have been established to handle the growing caseload in this area of the law (most of them petitions for divorce). Our study is primarily based on an ethnographic study of one of these special family courts in southern China. By comparing this new pragmatic discourse with the old moralistic discourse it replaced, we offer an account of the new, rapidly developing norms of Chinese courts.

The Pragmatic Discourse

Our conceptualization of the meaning of discourse is inspired by two rather disparate theoretical traditions—the linguistic anthropologists' view of discourse as language in use (Reference DurantiDuranti 1997; Reference MertzMertz 1994a, Reference Mertz1994b, Reference Mertz2007; Reference SherzerSherzer 1987; Reference Silverstein and LucySilverstein 1993, Reference Silverstein2003) and the Foucauldian approach that treats discourse as distinctive ways of talking and interpreting practices that constitute the objects of which one speaks (Reference FoucaultFoucault 1972; Reference MerryMerry 1990; cf. Reference CameronCameron 2001). Drawing from Merry's study of discourses in two lower courts in New England (Reference MerryMerry 1990), we approach discourse as a systematic mode of explanation, a more or less coherent theory of action. The study of discourses (in the plural form) weaving in and out of the discussions of particular problems in court suggests how wider cultural frames and values are pulled into the discussion of law, or rather how legal discussion is at the same time both cultural and moralistic. According to Reference MerryMerry (1990: 115), courtroom discourse often deviates from the legalistic understanding of rights and wrongs, facts and truth, and delves into a different modality of justification. For example, therapeutic discourse suspends the use of legalistic devices such as “intent” and “act” to determine a person's culpability and instead “takes the form of excusing offensive behavior, since action is environmentally caused and therefore is understood and accepted” (Reference MerryMerry 1990: 114–15). Merry argues that in the United States, this discourse was first used by the helping professions to fix broken relationships and has since been appropriated by legal professionals to deal with domestic relations situations such as divorce cases that arrive at the doorsteps of local courthouses (see also Reference FinemanFineman 1988, Reference Fineman1991).

Similarly, the pragmatic discourse we identify in the courts of China is a form of institutional discourse organized around the structure of a civil trial. It is shaped by judges' preference for mediation. While pragmatic discourse, with its nonlegalistic nature, shares some similarities with therapeutic discourse, the two differ markedly. In pragmatic discourse, the judge seems to assume the role of a helping professional, but rather than fixing a broken relationship, her ultimate goal is to resolve the dispute.Footnote 1 A judge does not address who is wrong and who is right or what is reprehensible and what is laudable. As will be shown, pragmatic discourse takes problem solving as its goal. Unlike their predecessors in the early period of reform (circa 1980s), judges today do not investigate the causes of a deteriorating relationship or reform a couple through ideological education (Reference HuangHuang 2005). The significance of pragmatic discourse lies in the fact that it has fundamentally redefined the “natural attitude” of the courts toward divorce as a social act; the courts no longer regard divorce as a taboo, but rather as an inevitable reality. More specifically, pragmatic discourse has the following characteristics.

First, it is amoral. Moral discourse was once the dominant discourse in Chinese family law. It was used to educate parties who were at fault and who, in turn, would be asked by the courts to reconcile. A judge in a family court today is not interested in knowing whether a wife is virtuous and filial or if her husband is adulterous or emotionally abusive. In short, the judge is less interested in saving the marriage than in coming to a resolution. The new pragmatic discourse sees divorce as part of the new social reality in China today. While litigants relying on moral discourse in the past could find an ally in many Chinese judges, they now face a more cynical bench, one that is often indifferent to moral pleading and the accompanying strong emotions. Second, it acknowledges divorce as part of China's present reality. Statistical evidence suggests that in many urban areas, the divorce rate has been soaring, with some major cities hitting the 50% mark (Reference YardleyYardley 2005). Courts no longer see themselves as institutions whose role is to save failing marriages by “judging”—that is, the authoritative stating of legal-cum-moral norms in their judgments coupled with an array of mediation tactics aimed at discouraging litigants from divorcing. The primary function of courts today is to deal with the consequences of divorce and to determine the respective rights and responsibilities of the husband and the wife. Questions in this area include the property holdings in the possession of divorcing spouses and decisions involving custody and child support obligations.

Third, parallel to the rise of pragmatic discourse is an emerging self-limiting conception of the role of the courts. Despite its much publicized birth control policy, the Chinese state is in fact withdrawing from family life (Reference PalmerPalmer 2007). Not unlike what Reference Friedman and PercivalFriedman and Percival (1976) identified in their study of the primary function of trial courts in the United States, Chinese courts have undergone similar changes in their role in family law—from dispute resolution to the administrative processing of routine cases. Although a court can still, in principle, prevent a plaintiff from divorcing his/her spouse in a contested divorce, judges know that they will eventually run out of legitimate reasons if a litigant is persistent enough. The remaining power of the courts is to impose “transaction costs” on the parties who seek to divorce. Transaction costs take various forms—for example, prolonging the process by denying a first-time divorce application, bargaining for more money in terms of child support or property redistribution for the weaker party in a divorce, usually the wife. These transaction costs are not imposed to deter a person from divorcing; rather, their purpose is to mitigate the power differential between a divorcing couple and soften the financial blow to the weaker party. Pragmatic discourse is therefore a product of this self-limiting realization of the courts today.

Studying Courtroom Discourse in South China

The episodes analyzed in this article are taken from trials that we attended in December 2011 at a district court in City Z in Southern China. Located at the heart of the Pearl River Delta, the most affluent region of the country, this city's gross domestic product per capita reached USD 11,000 in 2010. It has thus attracted a large number of migrant workers from the hinterlands. Of the 800,000 residents in the jurisdiction of the trial court in which our sampled trials were heard, 300,000 were registered migrants. While the official language is Mandarin, a significant proportion of the population speak Cantonese as their everyday language.

There were two main parts to our data collection (cf. Reference He and Hang NgHe & Ng 2013). Gaining access to the court through personal connections, we were introduced to the judges hearing the cases and were allowed to sit in the courtroom during the whole trial process. Two judges, both female, were designated to hear divorce cases. We were there for about one month. It was the busiest season for the court, so much so that extra court sessions were sometimes conducted on Saturdays. Hence, during the period we conducted our fieldwork, we saw both judges in action on an almost daily basis. There was also a third judge, a male, middle-aged judge seconded from a nearby county court who was there to help clear the backlog of cases. In total, we observed more than 20 trials. Civil trials in China proceed at a crisp pace; a trial typically takes only one court session, either a morning or an afternoon. Some of the trials we observed were as short as 10 minutes (usually because the defendant did not show up), but in most cases, the hearing lasted one to two hours.

Recording court proceedings is not permitted in China. During our fieldwork, we relied mostly on our written notes. The short sessions made extensive note taking a less exhausting exercise. Toward the end of our fieldwork, the judiciary of China kindly agreed to make copies of the official court transcripts of a number of the trial sessions we had attended available to us. The transcripts had been prepared by court clerks who worked for the judges. The transcripts cited later are based on our own written notes and the official transcripts. While our transcripts are comprehensive, they are not detailed enough to allow us to pay attention to micro features such as lapses, overlaps, and silences or paralinguistic features such as stress and intonation in a detailed way. That said, we consider our transcripts to be sufficient for the purpose of our analysis. Despite its limitations, our data are valuable considering the very limited amount of sociolegal research on the courtrooms of China. Names and other identifiers have been changed to protect the identities of the litigants and counsel involved.

The second part of our data collection consisted of interviews with the presiding judges and with other judges experienced in handling divorce petitions. We hoped to understand why the judges asked certain questions and what evidence constituted the basis of the court's decisions. As a group, they were candid about their opinions on the performance of the parties, the weight they gave to certain evidence, and their rationale for their decisions. The interviews lasted between half an hour and an hour.

Because our fieldwork site is located in the Pearl River Delta, a region with quite distinctive socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, we made further efforts to verify whether the pragmatic discourse we identified from this court is a unique regional phenomenon or one that is more widely used across the country. We telephone interviewed judges experienced in divorce cases from the provinces of Jiangsu, Guangxi, Zhejiang, and Shaanxi. We also compared our findings with the literature on divorce courts in which the data were collected from northern parts of China (Reference ChenChen 2007), other regions of Guangdong (Reference HeHe 2009; Reference LiLi 2011; Reference WuWu 2007), Shanghai (Reference HuangHuang 2010), and Gansu (Reference WangWang 2007).

Changed Role of Judges in Divorce Cases

Under the influence of the Soviet Union and other civil law countries, the style of court hearings in China had, until recently, been inquisitorial. Judges in China were responsible for gathering evidence for the cases they handled. In the area of divorce, mediated reconciliation was once the standard way for judges to handle petitions. Before the 1990s, most divorce petitions were mediated or spouses were pressured to reconcile before a final decision was made (Reference HuangHuang 2010). Reference HeHe (2009: 86–87) describes the old system as follows:

[T]he judge in charge first conducts several on-site investigations to determine the real reason for the divorce. Then in a ceremonial setting in which all relevant parties are present, the judge employs ideological indoctrination emphasizing family and social stability to criticize or educate the couple. The tremendous familial, community, and official pressures marshaled through the courts, together with some material inducement, make it almost impossible for the divorce petitioners to resist. More often than not, they have to confess their “mistakes” and “naiveties” and reach the so-called reconciliation arranged by the courts with the other party.

Maoist courts were very reluctant about approving contested divorce petitions and insisted instead on mediated reconciliation, even for cases where the petitioner had reapplied multiple times (Reference HuangHuang 2010: 177–78).

In part to relieve the heavy burden incurred by the inquisitorial process, the state revised court procedures in the 1990s, placing more responsibility on individual litigants to bring and prove a case (Supreme People's Court Work Report 1996). The policy slogan in Chinese courts is now dangshiren zhuyi (litigant as the center). The burden of proof is now on the litigants, not the judge (Reference WooWoo 2003). The role of judges in divorce cases is consistent with this change in law and policy. While mediation is still a compulsory stage in court hearing proceedings, judges rarely conduct an investigation in preparation for a trial (Reference HeHe 2009). Their decisions are also heavily, if not solely, based on the admitted evidence provided by the litigation parties and the examination of witnesses conducted during court hearings (Reference WooWoo 2003: 132).

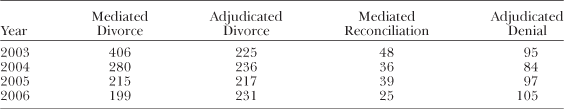

Table 1 shows the recent statistics presented by Reference HeHe (2009) on the outcomes of divorce cases handled by Court P (a court in Guangdong). The figures are markedly different from those in the pre- and early reform period. Approvals are now three times higher than denials or reconciliations. Judges today are less hesitant to render a divorce decision, and they generally find a genuine reconciliation difficult to achieve. Even in contested cases, the courts, while rendering a denial, simply tell the petitioners that a divorce will be granted if they petition again after six months (Reference HeHe 2009). Similarly, another report from the hinterland Gansu province suggests that approvals make up 64% of the decisions on divorce petitions in the province (Reference WangWang 2007: 207). Reference HuangHuang (2010: 178–80) also found that in Shanghai and other parts of China, starting in the 1990s, the courts rendered divorce decisions for cases that would have definitely ended with reconciliation in the Maoist period.

Table 1. Outcomes of Divorce Cases at Court P, Guangdong Province, 2003–2006

Source: He (Reference He2009: 90).

There are four stages in a Chinese court hearing process: court investigation, court discussion, court mediation, and decision announcement. Although in most cases, the first three stages of a court hearing are clearly separated, sometimes, they are combined. Despite recent reform, a Chinese civil trial remains a judge-led procedure. In the first two stages, the litigation parties are allowed to question each other's arguments and evidence. But even during the investigation stage, the judge decides who can speak, what evidence can be questioned, and what questions can be asked. In short, she controls the pace and direction of the investigation. In the course of our fieldwork, we often saw judges interrupt the speeches of litigants and their representatives, including some lawyers. This dominant role makes the judge “the third party” (Reference Philips and GrimshawPhilips 1990), and probably the most important party, in a trial. From our interviews, we know that questions raised by judges during trials usually have a direct bearing on their verdicts. This means that the interactions between a judge and litigating parties are more important than those between litigants. In a Chinese trial, unlike a common law trial in which the battle of discourses mainly takes place during the process of cross-examination (Reference Atkinson and DrewAtkinson & Drew 1979; Reference MatoesianMatoesian 2001; Reference NgNg 2009), the power relations that structure legal conflicts are mainly played out in the interactions between the judge and the litigants.

The significance of the judge–litigant interaction becomes even more apparent in the mediation stage. It is at this stage that the judge makes efforts to convince the parties to accept a deal. As Reference ChenChen (2007: 393) describes, “the judges' role in the process is controlling and dominant; they can easily reduce, revoke, or cancel the requests of the parties.” There are obvious reasons why judges want to facilitate successful mediation. In principle at least, the judges rid themselves of the worry that a judgment cannot be enforced when both parties agree to a mediated resolution; the judges also rid themselves of the fear that the judgment would be appealed because a mediated agreement is, by definition, voluntary. Finally, judges can spare themselves the trouble of writing a judgment. As a result of the renewed emphasis on mediation over adjudicatory justice in the past decade (Reference Fu, Cullen, Woo and GallagherFu & Cullen 2011; Reference HandHand 2011; Reference MinznerMinzner 2011), many courts, including the one we visited, require judges to mediate a certain percentage of the cases they handle. Of course, many judges also believe that both parties are better off with a settlement. All of these considerations compel judges to adopt a heavy-handed approach to litigants during in-court mediation sessions. Official statistics indicate that the adjudication rate of family and marriage cases has steadily declined, from 38% in 2002 to 27% in 2010, while the mediation and withdrawal rates have increased correspondingly (China Law Yearbook: various years). Nonetheless, the overall mediation rate for civil and commercial cases only reached 39% in 2010 (China Law Yearbook 2011), while the rate in the 1950s and 1960s was about 85% (Reference LubmanLubman 1997).

Moral Cynicism

The data analyzed were primarily drawn from the cases handled by three judges within about one month. We observed the open-court proceedings for the cases included in this study. These cases were conducted in a summary format in which a single judge presided over a case. About half of the litigants were unrepresented. Relatives of both parties often sat in on the hearings.

Pragmatic discourse signifies that a stronger noninterventionist tendency is shared among judges who preside over family courts in urban China today. The judges we observed all seemed to subscribe to the principle “I won't judge unless I have to.”

Due to the nominal fault-based divorce system, a simple uncontested divorce application is just a formality. One of the most uneventful trials we observed involved a petition made by a couple who had been married for over 20 years. The husband and wife appeared before the judge together, sitting on opposite sides of the courtroom without much eye contact or interaction (technically, the husband was asking for a divorce from his wife; hence, he was the plaintiff and the wife was the defendant). There was no dispute between them over the distribution of their property. They have no dependent children—their only son is already 22-year-old. The husband cited “breakdown of emotional relationship” as the grounds for the divorce. The presiding judge, Judge Wang, a regular family court judge who is now in her fifties, made no further inquiries about the couple's current relationship. She accepted the petition for divorce and asked the soon-to-be-divorced couple to sign off on the court documents. The entire hearing lasted about 15 minutes.

There was another straightforward case in which both sides wanted a divorce and there were no disputes over property distribution or child custody; this time, the defendant (the plaintiff's wife) was absent. Judge Wang went through a set of routine questions with the husband. The man, in his late fifties, said there was no longer any love between him and his wife. He had applied for a divorce before the court once before, but later agreed to withdraw his case. This was his second time of filing for divorce. He told Judge Wang that he had left his family in 2008 and had been separated from his wife since that time.

Toward the end of this short trial (which lasted about half an hour), the man said to the judge,

[Plaintiff] In fact, I don't want to divorce. We once both dreamed of a wonderful future together. Throughout all these years of conflict, we've talked and tried to iron things out. Now, there is really no road for me to walk [emphasis added].

[Judge] So do you want a divorce or not?

[Plaintiff] I insist on a divorce.

The formulaic expression “no road to walk” was used by the applicant to convey how reluctant he was to choose to divorce. He could not go on (no road ahead) even if he wanted to. By saying this, he tried to avoid blame for the divorce by implying that it was not his fault that the marriage had to end. This kind of moralistic discourse was typical under the Maoist system. A judge in the past would at least have asked the litigant to elaborate on why he had “no road to walk” and sought to encourage the litigant to work on his marriage (Reference HuangHuang 2005). However, under the new “pragmatic” regime, the litigant in this case was greeted coldly by the judge: Judge Wang asked, “So do you want to divorce or not?” Realizing that the judge was not in the mood to moralize, the man immediately dropped his moral pretensions and responded unambiguously: “I insist on a divorce.”

In the cases we heard, some of the wives accused their husbands of infidelity. As previously mentioned, whereas in the past, judges were likely to investigate the truth of an accusation, today, they tend to ignore an accusation if both sides agree to a divorce—from a bureaucratic point of view, this is reason enough for a divorce judgment. In a case we observed involving a young couple in their early 30s, the wife accused her husband of having cheated on her twice. Both spouses, however, had agreed to divorce—their dispute was about child custody. Although the woman made the allegation of infidelity several times, the judge, Judge Chen, a young woman in her 30s, made no inquiry into the allegation during the trial.

Other recent studies on the topic have also shown that divorce is now treated in a matter-of-fact fashion in China. In a case where a husband filed for divorce because his wife refused to have intercourse with him, Reference HeHe (2009: 92) observed that “[u]nlike the pre-reform style of practice, the judge here was not concerned with the real cause of the divorce.” In this case, the judge even suggested that such an inquiry would fall into the area of the couple's privacy and believed that her role was to grant or deny the divorce petition. In another case in northern China documented by Reference ChenChen (2007: 397–98), when the wife hoped to insert “the real reason for the divorce is that the plaintiff had extramarital affairs” into the settlement letter, the court clerk responded, “Why bother, as you already agreed to divorce?” The defendant later complained that the court only followed a proceduristic process in handling every divorce case without offering an opportunity to litigants to explain themselves. The defendant said that the court did not empathize with many litigants who experienced personal hard times (Reference ChenChen 2007: 397). As yet another example, judges frequently use the saying haohe haoshan (“happy engagement, happy separation”) in a mediation (Reference WuWu 2007: 301) in an effort to convince the divorcing parties to accept reality and move on. Taken together, these examples show how far the new system has abandoned the Maoist system that treated divorce as almost intrinsically socially destructive and something to be discouraged at all costs.

How then does this new pragmatic discourse negotiate gender equality and women's welfare? Later, we analyze one case. Through the courtroom dialogs between the judge and the plaintiff, we can see how pragmatic discourse is creating a new social reality and thereby both presenting and limiting the options available to women facing divorce.

Our main example draws on a trial brought before Judge Chen involving a contested divorce. In her early 30s, Judge Chen is part of a new generation of judges who are college trained in law. The parties in this case were a migrant couple in their early 40s, Mr. and Mrs. Li, originally from the mountainous areas of Guangdong, who had been married for 11 years and had a 10-year-old daughter. Mr. Li worked for the postal service as a contract worker and Mrs. Li, who was uneducated, worked as a janitor for a cleaning company. They were a typical working-class migrant couple who had left their hometown to move to the city in search of a more financially rewarding life. Mr. Li earned around 1800 yuan a month, and Mrs. Li's monthly income was about 1400 yuan. The couple had contributed a large amount of their income to repay the husband's family debt. Shortly after the debt had been paid off, the husband asked for a divorce. He said that he did not have emotional feelings for his wife. He also stated that his wife did not get along with his parents. In Chinese legal terms, Mr. Li was using “ruptured emotional relationship” as grounds for divorce.

As scholars have pointed out, the acceptance of “ruptured emotional relationship” as a legitimate reason for divorce in the current Chinese system, coupled with the lack of on-site investigations and cross-examinations of witnesses by judges, means that the system borders on a de facto no-fault policy (Reference DavisDavis 2010, Reference Davis2011; Reference HuangHuang 2010: 204–08). Mrs. Li made her objections to the proposed divorce clear to the judge. At the beginning of the trial, she asked the judge whether the trial was merely a matter of formality and whether it was the case that the court was going to approve her husband's application. Judge Chen assured Mrs. Li that she had no preconceived idea about the outcome.

In court, Mrs. Li contended that the real reason her husband wanted a divorce was because his family debt was now paid off. She alleged that his economic well-being had now improved and that he wanted to abandon her. More important, her in-laws wanted a boy in the family, but that remained a pipe dream as long as she remained their son's wife because she was already too old to bear another child.

The contested nature of the petition notwithstanding, this was a simple divorce case that did not involve complex property redistribution and documentary evidence. Neither side was represented by lawyers. The judge listened to the arguments made by the husband and the wife (mainly the wife) during the investigation phase of the trial, which lasted for about an hour.

Judge Chen then moved on to the mediation stage of the trial. The judge had two options—either to persuade the husband to drop his petition for divorce or to persuade the wife to agree to divorce. The judge chose the latter, a choice indicative of the new realistic approach. She first asked Mr. Li whether he would consider reconciliation. When he refused, Judge Chen showed little interest in trying to change his mind. She seemed to have made up her mind that the husband could not be persuaded to stay in the marriage. She then quickly turned to Mrs. Li.

In a dialog lasting approximately half an hour, Judge Chen tried to persuade Mrs. Li to agree to a divorce. In the course of this long discussion, the judge attempted, through iterations of the pragmatic discourse, to undermine the wife's traditionalistic ethics and to steer her toward seeing what she saw. The exchange between the judge and the litigant, in the forms of questions, answers, parries, and rejoinders, exposed the elements of pragmatic discourse. Judge Chen and the two litigants all spoke in Mandarin; the litigants, especially Mrs. Li, spoke with a noticeable Cantonese accent.

As will be shown, even though the mediation talks proceeded in the standard question-and-answer format, they did not follow a strict courtroom format. Many of the questions were rhetorical devices deployed by the judge to persuade Mrs. Li to give up her marriage. Similarly, Mrs. Li often did not give direct answers to the judge's questions; often, she offered what Reference GoffmanGoffman (1981) would describe as a “response” to try to explain herself in light of the challenges implied in the questions.

Transcript (1)

[Plaintiff] I told her, if she agrees to a divorce, I am willing to give her 10 000 yuan.

[Judge] You'll give her 10 000 yuan, right?

[Plaintiff] Yes, for the time she wasted on me.

[Judge] So, if he gives you 10 000 yuan, would you agree to a divorce?

[Defendant] For 10 000 yuan, of course I would not agree. He's completely …

[Judge] How much money would be a fair sum for you?

[Defendant] I don't want money. It's our marriage. I think we can tolerate each other a bit more and we can reconcile. That's what I want.

From the very beginning, Mrs. Li expressed her unwillingness to bargain. This episode is illuminating for the purpose of understanding the implicit perspective from which pragmatic discourse operates. In other cases involving couples who are willing to bargain, the judges' role is to facilitate the process, to nudge the parties toward a compromise, and sometimes to prevent the stronger party from taking advantage of the weaker party. But, this episode was different: the pragmatic discourse revealed itself as a meta-discourse—facing a litigant who did not want to bargain, it had to justify first of all why it is good to bargain at all. In the process, it framed the wife's insistence on keeping her marriage as irrational and problematic. In excerpt (1) earlier, the judge talks to Mr. Li. She wants him to offer his wife some compensation. Mr. Li readily agrees and offers 10,000 yuan for the time his wife has wasted on him, but Mrs. Li says that she does not want to bargain.

Transcript (2)

[Judge] Let me tell you now. You see, you two have been together for many years already. The marriage problem you have, you know it in your heart way better than I do. Can this marriage continue? Right? … What can I say about him? You can't tie him down by your side! Let's just say the court rules against divorce this time: will he come back and live with you? This is what you really need to think about, right? I know that as a traditional woman, you perhaps think that divorce is not good; it is not good for your child either. But this is the reality: He doesn't want to live with you anymore; he insists on a divorce.

[Defendant] He …

[Judge] Your hope is to maintain the integrity of your family. Your hope is wonderful. But can it be fulfilled?

In this excerpt, Judge Chen questions the sanity of the defendant's decision to insist on her marriage continuing: the writing, as it were, is on the wall. The judge's way of describing the defendant's marriage is controlling in the sense that it leaves very little space for Mrs. Li to say that her marriage is fine. Her question is put to Mrs. Li in such a way that it already marks an affirmative answer as delusional—you know more than I do about your marriage and even I can tell that your marriage is dying.

Judge Chen moves on to establish another “fact” that structures the subsequent exchanges: a woman can no longer keep a man from leaving an unhappy marriage. She appeals to the fact that marriage is a covenant between two free individuals. The judge's characterization of the husband as a free man determined to leave rather than as a flawed individual to be educated is evidence of the bigger shift from the previous moralist discourse to the current pragmatic discourse. As mentioned, the new pragmatic discourse adopts a firm noninterventionist position in relation to an individual's decision to leave his or her marriage.

The judge then poses another question that further suggests the futility of Mrs. Li holding on to her marriage: “Let's just say the court rules against divorce this time: will he come back and live with you?” The question is rhetorical in the sense that it presumes a negative answer: the husband will not return. Still, the judge praises the defendant as a virtuous “traditional woman” (chuantong nuxing). This framing of Mrs. Li's identity as a nuxing is indicative of the gendered discourse that Judge Chen creates for the aggrieved wife. The term nuxing (“female sex”) was historically used by cultural critics of China to counteract the Maoist label of women as funu, a concept that viewed women as desexualized socialist comrades (Reference Barlow and GilmartinBarlow 1994). As used by Judge Chen, nuxing invokes the image of the traditional Chinese woman as virtuous, but also passive, dependent, and emotionally laborious. Loyal as she is, Mrs. Li is, as a nuxing, blind to the stark “fact” she is facing (and that the judge is eager to point out): “He doesn't want to live with you anymore; he insists on a divorce.” When the woman displays a hint of doubt, the judge follows that up quickly with another question that points to the pointlessness of playing the role of a virtuous wife: “Your hope is to maintain the integrity of your family. Your hope is wonderful. But can it be fulfilled?”

Transcript (3)

[Defendant] When she [the daughter] was young, one year old, I said what if we divorce … back then, he said that this absolutely wouldn't happen.

[Judge] Ah, you see, each of us here handles hundreds of cases.

[Defendant] He said it wouldn't happen, that it absolutely wouldn't happen. Now, you see, he just told me that he wants a divorce. I don't know.

[Judge] In fact, I think this thing called divorce is very normal. All couples when they get married say they are not going to divorce; they say they will stay together forever. No one thinks about divorce when they marry. But in reality, every year there will still be hundreds of people sitting here telling me they want a divorce. That's why I think it is very normal, right?

[Defendant] But …

[Judge] I think the more rational or more effective way to deal with this problem is for you to propose some demands and see if both sides can negotiate on them.

[Defendant] What kind of demands? He has to give me money.

[Judge] Yes.

[Defendant] But he has no money to give me.

[Judge] He now agrees to give you 10 000 yuan.

[Defendant] 10 000 yuan? I worked for his sake. Who am I in his eyes? He is not treating me like a wife. He's treating me like a messenger, like an entertainer. He is treating me like a stranger.

[Judge] But if there is no divorce, he won't give you 10 000 yuan. Will you then think that he is treating you like a wife?

[Defendant] He doesn't give me money, but that's okay.

In this excerpt, Mrs. Li tells Chen that her husband had once promised never to leave her. The judge's response is unsentimental: promises are made to be broken. Once again, the pragmatic discourse is at work. It normalizes divorce. Chen does this by citing her own experience as a judge who hears hundreds of divorce petitions each year. It is instructive to note that she uses the Chinese words zheng chang, which mean not just common but, more significantly, normal. The normalization of divorce is a far cry from the old moralistic discourse's characterization of divorce as pathological. Rationality, not emotion, is what is required to deal with this “normal” life event. Hence, the judge asks Mrs. Li to deal with the situation in a rational manner, meaning that she should get what she can from her estranged husband before it is too late. In using the word “rational” to describe the option of seeking compensation and then moving on, the judge implies that Mrs. Li is clinging to her marriage, which would have been admired under the old system, but is now considered “irrational.”

The judge had already proposed that Mr. Li should offer a one-time compensation payment to his wife and Mr. Li had agreed to this. She then asked Mrs. Li if she had a counter-offer. For the judge, monetary compensation seemed to be the most realistic way of resolving the dispute. In this case, there were no legal mandates requiring Mr. Li to compensate his wife because there had been no domestic violence or extramarital affairs; the judge asked him if he was willing to use money to appease his distressed wife, to assuage her anger and frustration.

In the excerpt earlier, Mrs. Li seems to momentarily give in. She says her husband should give her money; and the judge says Mr. Li has already agreed to pay 10,000 yuan. But Mrs. Li's subsequent reaction shows that she has a different moral interpretation of money. She sees the settlement money not so much as a means of compensation, but as a moral token. That kind of money (10,000 yuan), she tells Judge Chen, is like treating her like a “messenger” or an “entertainer,” as anyone but a wife.

Judge Chen refuses to moralize. She tells Mrs. Li that names mean little. If she chooses to remain a “nominal” wife, her husband will not even give her 10,000 yuan. She asks, “Will you then think that he is treating you like a wife?” Mrs. Li sticks to her traditionalistic discourse—it is fine for her to receive no money if she can keep her marriage.

Transcript (4)

[Judge] If you think about it this way, doesn't it just make things worse for you? Right?

[Defendant] No, it doesn't. My daughter goes to school; no one will say to her, “Oh no, you don't have a father. Did he divorce your mom?”

[Judge] So many people are divorced. Nowadays, who will say this?

[Defendant] No, that's not the case …

[Judge] Besides, when you two divorce, you don't necessarily have to let your daughter's classmates and teachers know, right? Look, her father works in Guangzhou all year round. How can others tell? He will still visit his little child after the divorce.

[Defendant] How will people not know? Many will know. He said that I didn't give birth to a son. His family wants a son. He said that I'm too old now. I'm not able to have a son. This is what he said.

[Plaintiff] Actually, I said right at the beginning that they didn't say that. It's all your misunderstanding. …

[Defendant] So I misunderstood again! Your father said it when we were celebrating the New Year of 2009; when we went home on February 20, your father said that there are hundreds of thousands like the daughter I bore …

[Judge] Have you considered the real reasons why you don't want a divorce? You think it is better not to divorce than to divorce, but what in fact is better if you don't divorce?

[Defendant] I don't know this either.

[Judge] That's right.

[Defendant] I think …

In this excerpt, Mrs. Li indicates that she believes that it is better for her daughter if she and her husband do not divorce. At school, people will not be able to accuse her daughter of not having a father. The judge once again tells Mrs. Li that divorce is very common; besides, no one will know because her husband is constantly away from home and he will still see their child. It is in her rejoinder that the litigant reveals what she thinks is the true reason for her husband's insistence on a divorce—his parents want a grandson, but she is too old to bear another child. Mr. Li denies the allegation, but Mrs. Li remembers the date when her father-in-law said this to her. Judge Chen does not appear surprised. Among couples living in rural China, the desire for extended families to have a son is all too common. However, the judge does not make any further inquiry on the subject. Instead, she immediately turns the question back to Mrs. Li. She does not deny the gender inequality Mrs. Li faces. She just asks the pragmatic question—is not divorcing a better option for dealing with the problem? It is clear that as a legal institution, the court no longer uses the law to educate and reform.

Transcript (5)

[Judge] I want to ask you a question. The key question is do you think that you two can still stay together as a couple? Can he treat you like a husband treats his wife?

[Defendant] In this regard, both sides have to be more tolerant.

[Judge] Why should you be more tolerant? Perhaps if you divorce, you can find someone who genuinely cherishes you.

[Defendant] I don't think I will. Generally, we are deceived by others. This is not going to happen.

[Judge] Not necessarily. Let me describe the situation you are in right now in colloquial terms: ain't no difference between having a hubby and not having a hubby. Right? Why do you want to keep this “nominal without substance” marriage? Why don't you … besides, even if I rule …

As this excerpt shows, Judge Chen continues to ask Mrs. Li questions: “[Do] you think that you two can still stay together as a couple?”; “Can he treat you like a husband treats his wife?” These questions are meant to expose the “irrationality” of Mrs. Li's moralistic view of her marriage. Under the pragmatic discourse, names and titles matter little. The presupposition that her marriage means little or nothing is interactively reinforced when the judge repeats these rhetorical questions.

When Mrs. Li says that she and her husband can exercise more patience, Judge Chen again bluntly discourages her and then offers some consolation. Mrs. Li is uncharacteristically cynical in her response: She says that a woman of her background will only be deceived again. Judge Chen tells Mrs. Li that she really has nothing to lose. The judge uses the words “nominal without substance” (you ming wu shi) to describe the defendant's marriage. She says, colloquially, “ain't no difference between having a hubby (laogong) and not having a hubby (laogong).”

Transcript (6)

[Defendant] This is not the same. You people have no experience of this yourselves and so you don't know. My thinking is different from you people. He will still be good. He has to be; he has to try.

[Judge] But have you considered the other side of the picture? That is to say, because I am going to give a ruling this time, first of all I may allow the divorce or I may not. Let's just say I decide against divorce this time. But then what if he comes back in six months? What do you want me to do then?

[Defendant] When he returns to petition again, I will ask him to pay his daughter child support once and for all. Right? I want, I want, my daughter [weeping]. I have lived with him for ten-odd years. He said I didn't give him money for ten-odd years. You can. … you can investigate [weeping]. …

[Judge] Where are you now?

In this excerpt, Mrs. Li tells the judge that her thinking is different. It is important to point out that Mrs. Li used the plural second-person pronoun nimen in Chinese, referring to not just the young judge, but also to her even younger aide as a group. She says that people like the judge do not have the kind of problems that she has. Mrs. Li is referring to the gap between herself, an uneducated middle-aged woman in a failing marriage, and Judge Chen, a young, educated, and affluent professional woman. The judge does not respond to Mrs. Li's thinly veiled challenge. She responds instead by referring to the institutional reality that even if she rules against divorce this time, Mr. Li will simply file for divorce again later. Judge Chen now explains to Mrs. Li that the court will not and cannot force her husband to stay with her. Mrs. Li can reject the divorce this time, but eventually the divorce application will be accepted by the court and Mrs. Li could be left with nothing at all because the law does not require one party to compensate the other.

At this point, Mrs. Li breaks down into tears and begins to recount, in a random stream-of-consciousness way, the hardship she suffered for her husband during their years of marriage.

As defined by Reference MerryMerry (1990: 112), legal discourse is “of property, of rights, of the protection of one's self and of one's goods, of entitlement, of facts and truths.” But the conversations shown earlier were very much shaped by the judge's preference for mediation, an institutional preference that can also be found in family courts in the United States (Reference FinemanFineman 1988, Reference Fineman1991). During this process of mediation, the judge did not talk about rights and evidence. Pragmatic discourse is a cost-and-benefit analysis: What is the advantage of keeping the marriage? What is the point of prolonging it? So you think you are unfairly treated: how about if he compensates you?

In a sense, the judge in Mr. and Mrs. Li's case did talk about the eventual legal outcome. But her “legal” analysis served only as a background for strategizing. The fact that the husband could file for divorce six months later and was more likely to be granted a divorce next time only added to the pressure on Mrs. Li to deal with the matter pragmatically. The judge was determined to persuade the wife to accept divorce and get the best deal while she could. If the reality is that “it is impossible to force somebody to live with you if he does not want to,” then the law is not going to change the reality; rather, it accepts it as its starting point. This again illustrates the stark difference separating pragmatic from moralistic discourse.

Resistance

If Mrs. Li had known the law and could have afforded a lawyer, her arguments could have focused on the fact that their emotional relationship has not been ruptured. Indeed, there were many facts in the case that would have supported such an argument. At the court investigation, Mrs. Li stated that she and her husband visited each other and had an active sex life even though their work places were a distance apart (Mrs. Li mentioned that she wore a contraceptive ring at her husband's request). Their affection toward each other had been lukewarm for many years, so why should the marriage be terminated on that day? If she had raised this argument, the judge probably would not have said that her approval of the husband's application was just a matter of time.

However, given her background and lack of representation, Mrs. Li was unable to come up with a legally legitimate argument. Facing the suggestions of the judge and the pragmatic discourse, her responses were poorly organized and full of discursive shifts (cf. Reference Conley and O'BarrConley & O'Barr 1990; Reference HirschHirsch 1998: 94). As the question-and-answer sequence progressed, Mrs. Li became more introspective. Pushed by Judge Chen's battery of rhetorical questions, she went through painful debates with herself about her choice of continuing the marriage. She also seemed to be most disturbed by her husband's allegation that she was not a good wife. She said that she did not deserve to be abandoned. The defendant told the judge that she had contributed to the family and recounted how she had taken care of the plaintiff's parents. In her mind, her husband's allegation that she was not a good wife was groundless and as long as she conducted herself as a wife, she could not be abandoned.

As mentioned, Mrs. Li believed that her husband's and his parents' craving for a son was the real reason for the petition. If this had come before a court in the Maoist period, the judge would have undertaken a thorough investigation. If Mrs. Li's claim was found to be true, the judge would not only have rejected the petition, but would also have told the husband why he was in the wrong. After all, wanting to have a son was precisely the kind of feudal prejudices that the new China of the Communist Party had vowed to eradicate. A judge today will not judge unless he or she has to. “If he does not want to stay with you in a marriage, you cannot force him to do so” is the new noninterventionist motto of pragmatic discourse.

Transcript (7)

[Defendant] I don't understand what you said. I'm not cultivated.

[Judge] I am explaining things to you now. I'm explaining things to you slowly.

[Defendant] He is more cultivated. He can certainly win the argument. You think so too, Judge; you think he meant well.

[Judge] I don't think he meant well. I'm just trying to explain things to you, that is to say …

[Defendant] You explain things to me, but I don't understand.

[Judge] So you should listen. You can only understand if you listen.

[Defendant] How can I understand if I listen? You say divorce and it's divorce; you say go and date another man and then it's go and date another man. I am left with nothing.

[Judge] I am trying to …

[Defendant] I am left empty-handed.

Not being able to argue with the judge on the likely legal outcome, Mrs. Li can only resort to a critical commentary on the nature of law. The defendant, despite her lack of legal knowledge, knows the world enough to realize that the deck is stacked against her. She tells Judge Chen that the court is siding with her husband because he is better educated. In the original Chinese, she says her husband has more wenhua, meaning he is more cultured. She says the judge seems to think that her husband means well because he is more cultivated than she is. She laments that the law does not empathize with the weak; she laments that the law does not empathize with the poor; and she laments that the law, above all, does not empathize with “uncultured” members of society such as herself.

Transcript (8)

[Judge] Okay, it is difficult to achieve mediation now. You should go back and think long and hard. Okay, just think about what I just said to you.

[Defendant] I don't understand what you said. You mentioned coming back for a second time. I hope we don't have to come back.

[Judge] I don't care if you understand or not. This is what the law stipulates. Today I have explained things to you so patiently; my goal is to help solve problems for both of you. When it comes time for me to rule, I don't have to discuss with you how I'm going to rule. I just base my ruling on the facts found and the law. This is a rather simple thing for me to do. I patiently said so much to you because I hoped that you could face up to your problem in a rational way and thereby solve the problem. The law is the same for everyone. The law applies the same rules to people who don't understand it. It won't offer special exemptions to those who don't understand the law. That's not how the law operates. You've got to understand this.

[Defendant] I don't understand.

At this point, Judge Chen decided to give up trying to mediate. In her opinion, what Mrs. Li was doing was not doing her any good. In excerpt (8), the judge points out to Mrs. Li that the law treats all people the same way, whether they understand the law or not. She says that her ruling does not depend on the fact that the wife has been a good wife or has contributed to the family; rather, it is based on whether Mr. and Mrs. Li still want to live together as a couple and whether there are some other alternatives, such as monetary compensation, to relieve the pain involved in solving the problem. Mrs. Li's response to the judge's lecturing is terse: “I don't understand.” The response itself is double voiced and displays Mrs. Li's resistance to the law. Its meaning is as much a professed lack of legal understanding on the part of Mrs. Li as it is a sense of disbelief in the current status of the law from this frustrated litigant.

Judge Chen and Mrs. Li were in fact arguing at cross purposes: the judge wanted her to receive maximal return for agreeing to a divorce, but Mrs. Li refused to consider divorce an option. In excerpt 9 later, which is from the end of the mediation, Judge Chen reveals, in the most explicit and concrete terms, what she can probably get for Mrs. Li from her husband—her daughter, a settlement upwards of 10,000 yuan, and, on top of that, perhaps a monthly allowance of around 500–800 yuan. But Mrs. Li is clearly in no mood to bargain. Her parting shot to the judge is, “In my marriage, there is no hope, only disappointment.” In Chinese, the pair of antonyms, shiwang (disappointment) and xiwang (hope), rhyme, and this only accentuates Mrs. Li's disillusionment with both her marriage and the legal system.

Transcript (9)

[Judge] When I said “mediation,” I meant this: Based on what you two agree to, for example, if the two of you agree that your daughter belongs to you [Mrs. Li] and he gives you 500 or 800 yuan each month, a sum which you can negotiate further, then we can write this down in the agreement and it has legal power. Also, about that money—he said that he will give you 10 000 yuan. Perhaps you think 10 000 yuan is too little and you want a bit more. We can write this down in the court's agreement; this also will have legal effect. Understand?

[Defendant] This only disappoints me; it gives me no hope.

[Judge] What did you say?

[Defendant] In my marriage, there is no hope, only disappointment.

In her written judgment, Judge Chen, as she hinted, ruled against the petition. She resorted to a technical argument. The plaintiff mentioned in his petition that he and his wife had been separated since 2007, but the judge wrote that he did not offer any evidence of that for the court to consider. This implies that should Mr. Li offer more concrete evidence of their broken marriage next time, he would stand a better chance of getting his wish granted. Meanwhile, Judge Chen was making the process inconvenient for Mr. Li. As mentioned, transaction costs for divorce applications in China are high, but in her judgment, Judge Chen does not mention what she told Mrs. Li, namely there is only so much that the court can do to postpone the inevitable.

Gender Inequality

This kind of pragmatic discourse also prevails in other parts of China. We informally telephone interviewed some judges we know from provinces including Jiangsu, Guangxi, Zhejiang, and Shaanxi who are experienced in divorce cases. Because these judges were included based on our personal connections with them, they do not constitute a systematic sample. Also, we did not observe the courtrooms in these provinces. However, the comments of the judges who work in urban regions also suggested a pragmatic attitude toward divorce cases. They pointed out that getting a good deal for the weaker parties is an important goal. We argue that this is due to the fact that the reform to redefine the role of the judiciary was applied by the central government from the top down. However, in rural areas where the community is more connected to traditional values and norms, judges seem to make a greater effort to repair broken marriages. Consequently, their discourse is comparatively more therapeutic.

For a long time in socialist China, it was difficult to obtain a divorce and judges, as agents of the expansive state, assumed for themselves the responsibility of rectifying the “mistakes” committed by estranged husbands and wives (Reference HuangHuang 2010). Such a legal arrangement became central to a series of unprecedented public debates in China that culminated in the 2001 amendment to the Marriage Law. The old law was criticized for allowing too much state paternalism and too little individual freedom and choice (Reference Alford, Shen and KirbyAlford & Shen 2003). Liberals argued that divorce could be desirable in some situations, freeing unhappy partners from unfortunate unions and sparing their children the prospect of growing up in acrimonious households (Reference LiLi 1998; Reference Pan, Li and MaPan 1999; Reference Xu, Li and MaXu 1999).

This freedom to divorce, coupled with the ideal of gender equality, a rhetoric touted by the Communist Party since the establishment of the People's Republic of China, soon gained a foothold. It promoted a new image of women as financially and emotionally independent people. In a report entitled “Legislation for Gender Equality,” Xia Yinglan, the chairwoman of the Family Law Research Association, suggested that “freedom of marriage” includes not just the “freedom to be married,” but also the “freedom to divorce.” She added, “Getting married happily and getting divorced rationally are both a pursuit of happiness; both reflect the progress of our time” (Chinese Women's News 2009).

But conservatives were worried that such a liberalizing approach would place women at a disadvantage because men dominated the new market society (Reference Zhu, Li and MaZhu 1999). In the end, the 2001 amendment was a compromise: it allows for “freedom to divorce,” but there is a price to pay if a party is “at fault.” The purpose of the amendment is to protect the weaker party, usually the wife, from exploitation by the stronger party, usually the husband. Indeed, the 2001 amendment seems to have been intended to stabilize families. For the first time, the law explicitly includes language that recognizes the state's interest in stability of marriage. But in some senses, the amended law is a throwback to a more moralistic fault-based system (Reference WooWoo 2003: 133). The amended law penalizes the party who attempts to conceal joint property in order to prevent the fair division of property in a divorce; furthermore, it allows the wronged spouse the right to request compensation from a spouse who has committed bigamy, illegal cohabitation, domestic violence, or desertion (Art. 46).

But that is the law on the books. As the ideas of freedom and equality took hold, divorce practices underwent radical change in the 1990s and 2000s. People are now given almost complete freedom to decide on the issues of divorce and marriage, so much so that persistent petitioning for divorce is now regarded as evidence of a ruptured emotional relationship, and as a result, divorce will be granted (Reference HeHe 2009). The system can now be characterized as a de facto “no-fault” system (Reference DavisDavis 2010, Reference Davis2011; Reference HuangHuang 2010: 204–08): spouses can divorce by choice. The old priority of preserving the conjugal bond has now been abandoned. While the law still punishes, inter alia, the party at fault, such as an abusive husband, when dividing up a couple's common assets, fault is no longer a necessary condition in the primary decision to grant a divorce. To some extent, this change has given women who want to end their marriage more freedom. Women constitute the majority of applicants who file for divorce (Reference WangWang 2007; Reference XuXu 2007). However, there remains the concern that divorce has become a way for husbands to preserve their new wealth and transfer it to second families that may better satisfy their emotional needs and their desires for a male heir. As a result, the Chinese government does not want to make the process too easy or too convenient. They also do not want to turn divorce into a mechanism that makes it possible for the economically stronger partner in a marriage to dispense with the weaker one.

It is in this context that the pragmatic discourse has entered the courts. It is in part a result of the renewed emphasis on mediation, as our case analysis has shown. The mediation rate is now a criterion used to assess judges' performance. As mentioned, judges are understandably motivated to get litigants to agree to mediation. But the new noninterventionist policy and the concomitant reform in trial procedures make it all the more necessary for judges to resort to mediation. They simply do not have the resources to investigate all of the divorce petitions that appear on the court dockets. But this new mediation game is different from the old idea of reconciliation. The reality is that judges today are more dispassionate. The ideological persuasion that had been effective until the 1980s is unheard of now (Reference HeHe 2009). Nor does the moral discourse referred to by Mrs. Li in the case above work. Her husband was clearly aware of how the system works. When he files for divorce for the second or third time, the court will eventually grant it. It is in this sense that, institutionally speaking, the Li's marriage was hopeless in Judge Chen's opinion. She wanted to get Mrs. Li something before it was too late. The pragmatic discourse is meant to be used by judges to “bargain” something for the weaker party. As we have seen, Judge Chen was not interested in assigning blame; rather, she was more concerned with keeping Mrs. Li from being left with nothing when her marriage inevitably ends.

It is therefore paradoxical to see that pragmatic discourse in practice can perpetuate gender inequality for some women, in that it mocks their traditional belief of keeping husbands married against their will. The pragmatic discourse avoids mentioning the power struggles between husband and wife or taking the side of the husband or the wife. Judges now presume that both spouses are ready and able to lead separate, independent lives after divorce. Men and women are also assumed by the courts to be equally responsible for the harm suffered by their children in the process and are asked to devote equal care to their children after a breakup.

As judges in China are eager to assume the role of alternative decision makers, they also contribute to the problems identified by Reference FinemanFineman (1991) in her critique of the rise of the discourse of the helping professions in mediating divorce and child custody cases—they try not to judge, they do not lay blame or find fault; rather, they look forward to the future and try to identify the best way forward for women and their children. But by dispensing with the quest to find fault, judges have also denied wives the moral high ground they formerly occupied in divorce litigation. Fineman also suggests that this pursuit of formal equality has sometimes overshadowed more instrumental concerns in divorce reform. For example, judges may ignore women's connection to their children in an attempt to cast them as unencumbered, equally empowered market actors (1991: 175). As seen, however, a key reason for Mrs. Li's objection to a divorce was what she firmly believed would happen to her daughter after it.

Furthermore, in this form of pragmatic negotiations, not unlike what law and society scholars found in their studies on the United States, women are often less experienced in financial negotiations (cf. Reference Conley and O'BarrConley & O'Barr 2005: 49). Mrs. Li, for example, was not at all prepared to talk about financial compensation under the assumption of “if divorced.” She was still insistent about maintaining her status as a lawful wife and stressing what she did for her family. Had she been more alert to money matters, she would have engaged in bargaining with her husband more proactively.

Pragmatic discourse is also constraining for spouses who are not ready to bargain. As Judge Chen stated, “In adjudication, you may not get any compensation.” The pragmatic discourse is constraining in the sense that compromise is the only viable option. However unwilling, a litigant has to accept that a judge's mediation is the best remedy the court can offer. In other words, it offers help in a coercive manner; a realistic and cooperative litigant will not leave empty-handed. In trying to provide better remedies for the wife, the law ironically paves the way for the reinforcement of patriarchy.

Even though the pragmatic discourse can be a reflection of the new social reality, its prominence as an institutional discourse also creates and reproduces this social reality. Specifically, it changes the way of talking and thinking about divorce. These new modes of talking and thinking are eventually, and subtly, inscribed in social action, sometimes with sad consequences for women. A wife who insists upon preserving her marriage is destined to be a loser in this system, even when the presiding judge is sympathetic and well-meaning. Nonetheless, it is often in the interactions between judges and female litigants that both the hegemony and resistance of law are revealed.

Finally, a comparison with other societies makes clear the complex relationship between pragmatic discourse and gender inequality. Pragmatic discourse in China is a product of the growing economic disparity between men and women as well as the rapid retreat of the state from the family domain. Its entry into the courtroom has weakened traditional moral discourse. While traditionalistic beliefs depict women inferior to men, they also offer some of the economically and socially most vulnerable women a thin layer of protection, often by obliging husbands to provide for their wives.

In her study of the practice of Islamic family law in Reference Mir-HosseiniIran, Mir-Hosseini (2001) demonstrates that some of the most patriarchal elements of Sharia law can in fact help socially disadvantaged women to achieve their marital goals. The lower-class women she studied in Iran fought their marital battles armed with a traditional moral discourse on family relations. They were thus in a stronger position to drive a hard bargain. Some women, for example, used the threat of mahr (a mandatory gift, or a promise thereof, given by the groom to the bride) in Islamic law to resist their husbands' requests for divorce, and they were backed by the courts.

In China, at least in its urban areas, the former dominance of the morality discourse has now been substantially undermined by the new pragmatic discourse, to the extent that it can no longer offer that thin layer of protection. The problem with the dominance of traditional moral discourse in patriarchal societies is that it is hegemonic in the sense that women must deal with this traditional discourse as the “default.”

For example, in her study of Swahili Muslim people in coastal Kenya, Reference HirschHirsch (1998) shows how women there can sometimes navigate the discursive asymmetry between men pronouncing (men can simply say “divorce” to resolve marital problems) and women persevering (women are expected to endure hardships in marriage). But even when they have developed a discourse of rights to fight for their welfare, that discourse of rights, unlike the pragmatic discourse we discuss here, cannot be deployed by women as “just another” alternative. It is more of a last resort, a discourse that can only be delicately deployed after women there have “proved” to the court that all of the other actions prescribed by the available moral discourses on marital conflict, such as more love and commitment, cannot salvage their marriages (Reference HirschHirsch 1998: 81–111).

This does not seem to be the case in China. If anything, the arrival of pragmatic discourse has removed traditionalistic moral discourse from the court scene. So understood, the pragmatic discourse promoted by the Chinese state may have unintentionally created some openings for other discourses to enter into the family domain. The problem with pragmatic discourse, as we have identified, is similar to the problem Reference FinemanFineman (1991) found with the discourse of the helping professions—it focuses exclusively on formal equality: Women are now “given” the right to divorce. But the interesting question to ask is this—Among the competing discourses, of which pragmatic discourse is one, can a new rights discourse that pays heed to substantive gender equality emerge in divorce law practices? In any case, the relation between pragmatic discourse and gender inequality is likely to be a complex one, a topic that clearly warrants more research in the future.

Conclusions and Implications

By studying courtroom discourse, we have illustrated a recurrent feature in divorce cases in China from our sample. Judges have ushered in a new discourse that encourages litigants to adopt a calculative attitude, to be compensated, and to get out of their bad marriages. Pragmatic discourse allows judges to pressure unwilling litigants by promoting the “new attitude” toward divorce as commonplace. Through the use of evaluative statements and rhetorical questions, judges often compare divorce favorably with the alternative of staying in a bad marriage. This is clear in the exchanges between Judge Chen and Mrs. Li. The Li trial is a vivid case of “doing gender,” in the sense that it is an active process reflecting the institutional shaping of gender relations (Reference CookeCooke 2006). In demonstrating the power of the law in creating a new legitimate understanding of the breakdown of some social relationships, our study of courtroom discourse unveils the ideological dimension of the law.

Through the perspective of pragmatic discourse, this article has shown how the courts reproduce gender inequality, particularly in divorce cases filed by men who want to satisfy their need for a male heir or a new romance. It also shows the dramatic shift from the Maoist emphasis on reconciling marriage conflicts to the new belief that some marriages will inevitably dissolve and the terms for ending a marriage must be negotiated. This shift has occurred because the courts, facing increasing caseloads and having limited resources, have had to identify a convenient legal solution for a question that is sociological in nature, as witnessed in the case analyzed. While in some nongovernmental organizations or in programs run by the Women's Federation, one may see a more therapeutic discourse rooted in the ideas of social work and human rights, courtroom discourse is dominated by a pragmatic approach aimed not at repairing a broken relationship or instantiating a moral code, but at finding a solution.

This genre of discourse is not completely different from the settlement language that other scholars have documented in the existing literature (Reference Greatbatch and DingwallGreatbatch & Dingwall 1989; Reference MerryMerry 1990; Trinder, Firth, & Reference Trinder, Firth and JenksJenks 2010), but the pragmatic discourse identified in China is tied to China's changing cultural and political milieu. While there is no denying that the use of settlement language in China is also driven by the practical demands for efficiency, there are many other factors favoring pragmatic discourse. As our analysis has demonstrated, it is a type of discourse derived from the institutional pressure on the courts to provide solutions in a society where traditional values and moral standards are losing ground. As such, it is as much a discourse that pushes for settlement as a meta-discourse that explicitly articulates why settlement is a better option for women.

Our study shows how legal discourse works to perpetuate gender inequality, albeit unintentionally, by offering “solutions.” The judges we observed and interviewed genuinely believe that getting something for women who insist on salvaging failed marriages is the best that they can do. But precisely because of the judge-cum-mediator role that judges like Chen play, the pragmatic discourse used in China gives a whole new meaning to the expression “bargaining in the shadow of the law” (Reference Mnookin and KornhauserMnookin & Kornhauser 1979). Despite the collective goodwill of judges, linguistic evidence indicates that this new discourse has become the pathway through which gender inequality is brought into being.