1. Introduction

There is a long-standing claim and ambition in international investment law that treaties and customary law contribute to economic development in countries hosting foreign investment. However, this claim remains controversial and has been hotly debated among academics.Footnote 1 The key function of IIAs has been and still is to ensure minimum protection of foreign investors and their investment.Footnote 2 The main reason why capital-importing countries are willing to agree to such protection is presumably to attract or retain foreign investment. However, some have pointed out that not all capital-importing countries follow this rationale.Footnote 3 Moreover, there have been numerous studies of whether and under what conditions IIAs increase the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) into contracting parties. Such studies concern, inter alia, the flow of FDI into developing countries generally,Footnote 4 into certain regions,Footnote 5 or into certain sectors.Footnote 6 So far, the findings of these studies are mixed. Nevertheless, emerging common denominators indicate that IIAs can effectively promote FDI into certain sectors depending on the protections included and circumstances of the country in question.

Against this background, we shall explore whether and how international investment law, understood as IIAs and their associated dispute settlement mechanisms, can support the right to development (RtD). This contribution takes as its starting point international law; the definition of the RtD under international law and the legal commitments undertaken by countries under IIAs. The intention is to move beyond a discussion of the legal compatibility of these two regimes of international law, and commence discussions on the potential effects of IIAs for the realization of the right to development. These are complex issues, which a legal scholar clearly cannot fully explore within the confines of an article. The ambition is therefore limited to provide some starting points from the perspective of international law for future analyses of the relationships and potential synergies between these two fields of international law and policy. Here, the assessments of effects of IIAs are based on literature reviews.

Both IIAs and the RtD have been increasingly divisive issues among countries in recent years. As has been extensively discussed elsewhere, there is increasing criticism against international investment law.Footnote 7 Many countries are reforming their IIA policies and revising their existing IIAs, most have (temporarily) stopped signing new IIAs, and a few have withdrawn from their IIAs. Countries sceptical of undertaking commitments under IIAs are at various levels of development and from all geographical regions.Footnote 8

Historically, the RtD has received broad support among countries, including in Article 55 of the Charter of the UN (1948),Footnote 9 Article 1 of the UN Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (1966),Footnote 10 and the UN Declaration on the Right to Development (1986).Footnote 11 However, attempts at gathering international consensus on the scope and content of the RtD have been unsuccessful, in particular in terms of identifying the role of FDI. As we shall further explore in Section 2, many developed countries have been strongly opposed to negotiations of legally binding rules on the RtD. However, some consensus seems to emerge in the context of political commitments, in particular the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).Footnote 12

After an introductory discussion of the relationship between FDI and the RtD (Section 2), the remainder of this article will explore three ways in which IIAs may affect the realization of the RtD. The main international commitments regarding protection of FDI are set out in bilateral and a few multilateral treaties, an increasing number of which are broader free trade and economic co-operation agreements. The extent to which these agreements offer effective protection to investors or investment depends on investors’ ability to bring cases to international tribunals in order to achieve economic compensation for treaty violation. Section 3 will explore how such protections relate to the RtD and SDGs.

Some IIAs have included provisions that aim more directly at facilitating flows of FDI. Rules that open countries to inflow of FDI are a mostly ‘post-colonial’ phenomenon in international law, going back three to four decades. In order to complete the picture of whether and how international investment law can support the RtD, Section 4 will briefly consider the potential for IIAs to expand the flow of FDI.

Responsibility and liability for negative effects of FDI in host countries are implemented through decisions by national courts and commercial arbitration tribunals based on contracts or domestic legislation of host countries. In some cases, the courts and legislation of investors’ home countries have played important roles. There are few rules and institutions in international law concerned with the responsibility and liability of foreign investors. Section 5 will briefly discuss the potential for IIAs to operationalize the responsibility and liability of foreign investors as a means to fulfil the RtD.

2. The relationship between FDI and the right to development

There is no authoritative definition of the concept ‘foreign direct investment’. Nevertheless, there seems to be high degree of agreement within international investment law that the following four elements are relevant when defining the concept: (i) Contributions of assets or money originating from abroad; (ii) a certain duration of the investment; (iii) an element of risk; and (iv) contribution to economic development in the host country.Footnote 13 While there is relatively broad agreement on the first three elements, significant disagreement remains regarding the fourth. Whether and to what extent the four elements are mandatory in order for an investment to qualify for protection under IIAs is context dependent and remains contested in many situations. As will be elaborated in the next section, many IIAs protect foreign investment regardless of whether it fulfils the four criteria.

Another common approach to the definition of FDI is to distinguish between ‘direct’ and ‘portfolio’ investment; the latter being a shorter-term placement of capital with a view to maximize return at as low a risk as available.Footnote 14 Portfolio investment would normally not fulfil the four criteria.

A broad range of investors may contribute FDI, e.g., state-owned enterprises, sovereign wealth funds, and international financial institutions. Here, our focus is on FDI originating from private parties (individuals and corporations) and from ‘public’ institutions that have some degree of independence from public authorities (e.g., state-owned enterprises and sovereign wealth funds).Footnote 15

The Declaration on the RtD contains norms that are relevant for FDI. Article 1(2) underlines the right of peoples to exercise ‘full sovereignty over all their natural wealth and resources’, and Article 8(2) establishes that states shall ensure ‘equality of opportunity for all in their access to basic resources, education, health services, food, housing, employment and the fair distribution of income’. These provisions indicate normative expectations regarding countries’ regulation of foreign investors and investment. By doing so, the provisions also establish a baseline for foreign investors’ legitimate expectations regarding the scope of protections they should receive from host countries under IIAs.

Recent initiatives to elaborate the RtD contain statements regarding the relationship to FDI. The 2010 Final Report of the High-Level Task Force on the Implementation of the Right to Development set out ‘criteria and indicators’ to implement the RtD. The Report emphasizes, inter alia, the need to secure stability of investment in order to reduce the risks of domestic financial crises; ensure that trade rules regarding performance requirements and protection of intellectual property rights do not prevent developing countries from enjoying the benefits of science and technology; and provide for fair sharing of the burdens of development by compensating for negative impacts of development investments and policies.Footnote 16 However, when considered by the Working Group on the Right to Development, the Report exposed significant disagreement among countries.Footnote 17 The Working Group has so far (mid-2020) been unable to reach consensus on the criteria. There was disagreement regarding the status of the criteria, the relative roles of countries at different stages of development, international institutions and private actors in taking measures to realize the right to development, and the substantive content of the criteria, including the mentioned elements.

In parallel with its work on criteria and indicators, the Working Group decided to discuss ‘standards’ for the RtD. Such discussions were based on a 2016 Report of the Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group that identified four standards.Footnote 18 The Report and its proposed standards make extensive references to the SDGs. Even if such references appear to be an attempt at building a bridge between the globally accepted SDGs and the RtD, the proposal met with significant opposition from countries.Footnote 19 The stark division among states was further exposed when the Human Rights Council decided to request that the Working Group ‘commence the discussion to elaborate a draft legally binding instrument on the right to development through a collaborative process of engagement, including on the content and scope of the future instrument’.Footnote 20 This approach replaced those based on criteria, indicators, and standards at the Working Group’s session in 2019.Footnote 21

In January 2020, the Chair-Rapporteur of the Working Group presented a ‘zero draft’ convention text following a process involving a Drafting Group and consultation of ten carefully selected human rights scholars.Footnote 22 The proposal contains five elements of particular interest here:

1) It claims to address the ‘biggest voids in the DRTD [Declaration on the Right to Development], that is, the lack of any reference to sustainable development’;Footnote 23

2) It launches a provision concerning the duties of ‘legal persons’, including foreign investors and associated inter-governmental institutions, to respect (i.e., ‘refrain from participating in the violation of’) the RtD;Footnote 24

3) The draft introduces several duties of states linked to their role as home states to foreign investors, including when negotiating investment treaties and regulating investors’ activities abroad;Footnote 25

4) It underlines the right and duties of host states to maintain sufficient policy (regulatory) space to fulfil the RtD;Footnote 26

5) It seeks to regulate the relationship between treaties and international institutions tasked with protecting the RtD and the interests of foreign investors, respectively.Footnote 27

These elements indicate that a key objective of the draft convention is to reduce tensions and promote synergies between foreign direct investment and the RtD.

So far, the approach that has gathered consensus among states has been based on the ‘sustainable development’ concept, including its focus on social, economic, and environmental development in an intergenerational context.Footnote 28 The link between FDI and sustainable development gathered some attention from the very start of the international community’s endorsement of sustainable development as a key policy objective in 1987.Footnote 29 In 2015, as the deadline for fulfilling the Millennium Development Goals expired,Footnote 30 the UN General Assembly adopted SDGs to be achieved by 2030.Footnote 31 While the Millennium Development Goals and Targets did not specifically address FDI,Footnote 32 some of the Targets of the SDGs are of particular interest.Footnote 33 Target 17.5 calls for the adoption and implementation of investment promotion regimes for least developed countries (LDCs). Moreover, other targets concern the use of foreign investment as a means to end poverty and hunger; achieve food security and improved nutrition; promote sustainable agriculture; ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy; and reduce inequality within and among countries.Footnote 34 Among the countries identified as being of particular concern, are ‘least developed countries, African countries, small island developing States and landlocked developing countries’, as well as ‘countries in situations of conflict and post-conflict countries’.Footnote 35 While the role of multinational enterprises is mentioned,Footnote 36 very limited attention is paid to their contribution of FDI. The Indicators established to monitor the achievement of the SDGs mention the role of FDI.Footnote 37 In general, the Targets and Indicators emphasize the positive role that FDI may play, and do not address the potential need to limit negative effects of FDI. This is in some contrast to the approach taken in the draft Convention on the RtD.

In parallel to the elaboration of the SDGs, the Third International Conference on Financing for Development adopted the 2015 Addis Ababa Action Agenda, subsequently endorsed by the UN General Assembly.Footnote 38 The Agenda points out important challenges regarding FDI: ‘Foreign direct investment is concentrated in a few sectors in many developing countries and often bypasses countries most in need, and international capital flows are often short-term oriented.’ It moves on to make it clear that foreign investors’ home and host countries as well as the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency have important tasks in ensuring that FDI contributes positively to sustainable development in a broader range of developing countries.Footnote 39

During the period after the so-called ‘Washington Consensus’ (the late 1980s),Footnote 40 it was argued that a basic distinction could be drawn between FDI in manufacturing and assembly – which would most likely be beneficial to development, and FDI in natural resources and infrastructure – which would most likely be harmful.Footnote 41 In recent years, consensus seems to emerge that the relationship between FDI and sustainable development is more complex and context dependent.Footnote 42 Moreover, UNCTAD has taken the lead in establishing relevant principles and guidelines for countries, inter-governmental organizations and stakeholders. A separate chapter on an ‘investment policy framework for sustainable development’ was included in its 2012 World Investment Report. UNCTAD proceeded to elaborate this framework based on ten Core Principles in 2015.Footnote 43 The starting point of the Principles is the overarching objective of promoting investment for inclusive growth and sustainable development. While the Principles build on UNCTAD’s decades of experience with providing investment policy advise to developing countries, they have not been formally endorsed by countries.

The consensus on the implementation of the SDGs stands in contrast to the significant disagreement regarding the RtD. Making progress on the implementation of the RtD has seriously divided countries, while the SDGs – including Targets and Indicators – have gathered consensus.Footnote 44 A key reason for these contrasting trajectories seems to be the rights-based framing and approach to RtD, in contrast to the aspirational and non-binding character of the SDGs. Moreover, the positive spin on the role of FDI in the context of SDGs, in contrast to the more problem-oriented approach to FDI in the context of the RtD, appears to be an important factor. The RtD approach emphasizes the freedom of the host country to limit the operations of foreign investors.Footnote 45 Moreover, the proposed criteria and standards as well as the draft Convention emphasize the responsibility of foreign investors’ home countries for contributing to sustainable development in host countries. The extent to which the relationship between FDI on the one hand and the RtD and SDGs on other is synergistic or conflictual, remains contextual and variable. In light of these considerations, countries are likely to have diverging opinions on the UNCTAD Principles.

While there is little doubt that the rules and institutions determining the rights and duties of foreign investors could play a significant role in resolving conflicts and promoting synergies relating to FDI, SDGs and the RtD, a key question remains regarding the distribution of responsibilities among foreign investors’ home and host countries. This question may have different answers depending on the respective abilities of the home and host countries. The distribution of responsibilities where FDI originates in an OECD country and targets a LDC should differ from cases where FDI goes in the opposite direction.

Target 17.5 of the SDGs points in the same direction by stating that countries should ‘adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least developed countries’. The Indicators adopted in order to measure achievement of the Targets, are key to understand how the UN, other IGOs, and countries will work to achieve the SDGs.Footnote 46 The Indicator for Target 17.5 is the number of countries that have adopted investment promotion regimes, and UNCTAD is assigned the role of following up the Target.Footnote 47 In its 2014 World Investment Report, UNCTAD estimated that given the current level of investment in SDG-relevant sectors, ‘developing countries alone face an annual gap of [US]$2.5 trillion’ and that the ‘role of private sector investment will be indispensable’ to fill the gap.Footnote 48 However, rather than focusing on the extent to which developed countries promote investment into SDG-relevant sectors in developing countries, UNCTAD has focused on the extent to which LDCs establish mechanisms to attract FDI. For example, in 2016 UNCTAD noted that 81 per cent of LDCs had established an investment facilitation agency.Footnote 49 Moreover, the specific SDG Targets associated with the various SDG-relevant sectors focus on official development assistance, and pay almost no attention to the role of FDI.Footnote 50

The approaches chosen when implementing the SDGs illustrate a significant dilemma regarding investment in SDG-relevant sectors. On the one hand, developing countries – LDCs in particular – have significant funding gaps in these sectors, and they sorely need FDI to fill the gaps. On the other hand, most SDG-relevant sectors are sensitive in the sense that public authorities need to ensure responsible and fair distribution of benefits throughout their population. Consequently, public authorities need to retain significant flexibility to adopt policy measures to achieve such distribution. The main way in which a host country can attract FDI into such sectors is by offering favourable conditions to the investors, including high return on the investment and low political risk. Such conditions limit public authorities’ ability (‘policy space’) to take measures if they find that FDI does not achieve or unfairly distribute benefits.Footnote 51

In sum, while underlining the right and duty of developing countries to apply policy measures to investment, the general framework for promoting FDI into SDG-relevant sectors relies heavily on limiting developing countries’ policy space. In the following, we shall study the role of IIAs. We will focus on the situation of countries with the most significant development needs; the LDCs and the low-income countries according to World Bank Income Groups.Footnote 52

3. Protection of FDI through IIAs and arbitration

The effects of IIAs for development depend on their ability to affect policy decisions of investors’ home and host countries as well as, more indirectly, the conduct of investors. Home and host countries establish rules in IIAs to protect the interests of investors. This section shall therefore first discuss the protectionFootnote 53 of FDI through IIAs. However, such international rules tend to have little effect unless they are accompanied by mechanisms to ensure effective implementation and/or compliance. In the context of IIAs, the dominant mechanism has been to provide investors right to initiate arbitration cases against host countries. After having mapped the legal bases for protection, we shall, therefore, explore the extent to which host countries are exposed to investor – state arbitration.

We will extend the analysis to protection of FDI through national legislation. The main reason is the focus on LDCs and low-income countries combined with, as we shall see, the limited participation of such countries in IIAs. Moreover, protection of FDI through national legislation has strong links to international institutions, in particular the World Bank and UNCTAD, and relies on international arbitration governed by international rules and institutions. Investment legislation is a significant alternative tool to protect FDI, and we cannot properly analyse the role of IIAs without considering such legislation. On this basis, we shall consider the role of international investment law in promoting the RtD.

3.1 Protection through IIAs

Prior to the IIAs we have today, there has been a long history of treaty-based protection of FDI. Johnson and Gomblett point out that the ‘notion of State responsibility for injuries to aliens began to emerge’ in the middle of the eighteenth century.Footnote 54 During this early period, colonial legal systems provided extensive protection to FDI. In host countries that were not colonized, which was the situation for many Asian and Latin American countries, FDI was protected through ‘a blend of diplomacy and force’ and eventually through ‘treaties resulting from the use of force’,Footnote 55 often referred to as ‘unequal treaties’.Footnote 56 Friendship, commerce and navigation treaties – primarily negotiated by the US with its trading partners beginning in the eighteenth century – eventually included some protections of property rights. After the First World War, such treaties expanded to protect ‘the rights of companies abroad, and also set out to strengthen the protection of private property’.Footnote 57

Countries established the current regime of IIAs during the period of decolonization and the emergence of new countries and economies in Eastern Europe and Asia. After a long period during which these treaties almost exclusively focused on protection of the interests of foreign investors, in recent years some countries have sought to adjust their content to reflect sustainable development needs. So far, the main effort has been to avoid negative effects for sustainable development. Some countries have also started to explore how IIAs can contribute to sustainable development.Footnote 58 Based on data from UNCTAD’s IIA Mapping Project,Footnote 59 we find that approximately 12 per cent of relevant IIAs include statements in their preambles on development-related issues.Footnote 60 Even more IIAs, almost 13 per cent, include substantive provisions on development issues.Footnote 61 In essence, substantive provisions are limited to exceptions, recommendations and political commitments. As such, they do not introduce legally binding obligations on states or investors to contribute to sustainable development. Nevertheless, they are likely to provide greater flexibility to countries who seek to promote sustainable and limit unsustainable FDI. IIAs containing such language go back at least to the first half of the 1980s.Footnote 62

The extent to which IIAs do or should provide protection to foreign investors regardless of whether the relevant FDI contributes to sustainable development, has been controversial. The general approach under IIAs has been to adopt broad definitions of investment and not to require contribution to development. UNCTAD’s coding of IIAs indicate that only approximately 4 per cent of IIAs exclude portfolio investments or include specific requirements that must be fulfilled to qualify as investment (e.g., duration or contribution to development).Footnote 63 More importantly, almost 65 per cent of IIAs allow countries to adopt national legislation that limit the scope of investments covered by requiring that investments be made in accordance with the host state’s legislation.Footnote 64 This means that the default rules of IIAs is that FDI enjoys protection regardless of its contribution to sustainable development, and that it is up to host countries to adopt legislation to deny such protection.

However, this is not the complete picture. Even if individual IIAs do not exclude investment that might be harmful to development, such investment might not be covered by the definition of ‘investment’ under the ICSID Convention, which is mentioned as a preferred or mandatory venue for dispute settlement in ninety per cent of IIAs.Footnote 65 Tribunals have disagreed on whether broad definitions of investment in IIAs can be set aside in individual cases based on a narrower investment concept in Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention.Footnote 66 This jurisprudence has considered four criteria for determining whether an investment should be excluded,Footnote 67 of which contribution to economic development has been the most controversial in arbitral practice.Footnote 68 Tribunals have referred to ‘economic development’ being mentioned in the preamble to the ICSID Convention, when justifying this as a relevant criterion.Footnote 69 The circumstances under which ICSID tribunals must exclude investment as not covered by Article 25(1) of the Convention remain unclear.

The literature on the extent to which IIAs may limit countries’ ability to take measures to achieve sustainable development is extensive.Footnote 70 The main substantive obligations in IIAs have traditionally been broadly phrased, in particular the provisions on fair and equitable treatment, full protection and security, non-discrimination, indirect expropriation, compliance with contractual obligations, and transfers. Generally, such provisions may seem to leave broad discretion to host countries. However, with the increasing inclusion of consent to arbitration in IIAs and resort to this means of dispute settlement by foreign investors, this discretion has been transferred gradually from host countries to arbitration tribunals.

Countries have become increasingly concerned that they will have to defend policy reforms before international arbitration tribunals and that such cases can be costly and time consuming.Footnote 71 Moreover, the extent to which IIAs actually have a chilling effect on countries’ policies to promote sustainable development regardless of initiation of arbitration cases, is hard to research. Even if preliminary findings are fraught with uncertainty, it seems clear that regulatory chill would essentially depend on consent to arbitration under the IIA in question.Footnote 72 This has led many countries to reform their IIAs in order to more clearly define the substantive protections and expand exceptions.Footnote 73

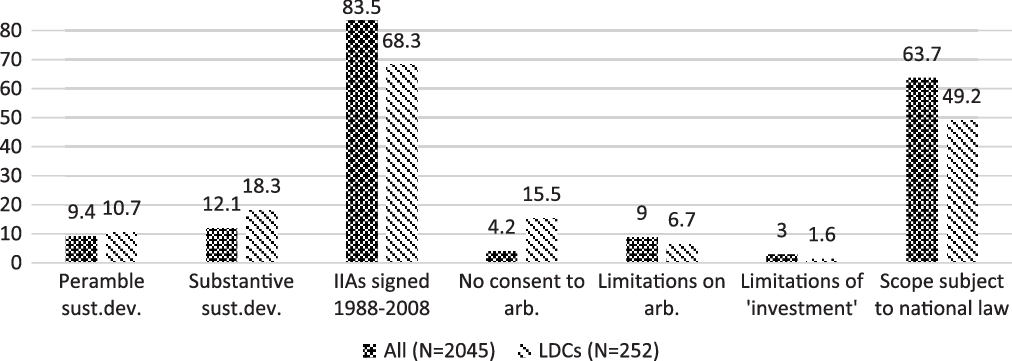

If we focus on the IIAs of LDCs, Figure 1 shows that these countries have a slightly higher than average share of IIAs that includes sustainable development relevant language. Moreover, a significantly higher share of LDC IIAs do not provide consent to investor–state arbitration (15 per cent). These factors indicate that the IIAs of LDCs have a somewhat lower than average level of protection. On the other hand, one factor points towards higher levels of protection within these IIAs; a significantly lower share of LDC IIAs excludes or allows countries to exclude certain categories of FDI.

Figure 1. Percentage of IIAs containing sustainable development relevant clauses.Footnote 74

In sum, there has been a general willingness and interest in including sustainable development language in IIAs with LDCs. Moreover, such IIAs may allow LDCs broader than average space to implement policy measures to fulfil the RtD and achieve SDGs. However, the differences that exist between LDCs and other countries in these regards are small and may not be important in practice. Nevertheless, there is a weak trend towards formulating IIAs with LDCs in terms favourable to sustainable development. The jurisdictional provisions of such IIAs, with the exception of consent to arbitration, indicate that the actual effects of such IIAs might be that LDCs enjoy a lower than average degree of policy space to take measures to promote sustainable development.

3.2 Exposure to international arbitration

Footnote Arbitration cases emerge in situations where a foreign investor claims compensation for economic losses caused by measures taken by the host state. In many cases, host countries can claim that the measures directly or indirectly promote sustainable development. However, there are also cases where the investor can claim that the contested measures are contrary to sustainable development; examples include environment- and natural resource-related cases.Footnote 75 In any case, all arbitrations represent a burden and risk to the respondent country, and may thereby have negative repercussions on the country’s ability to prioritize implementation of sustainable development policies. Access to arbitration can also have more systemic effects in providing predictability and security to foreign investors, and thereby facilitate investment into SDG sectors, as discussed above. On the other hand, such access can have a chilling effect on sustainable development policy initiatives.Footnote 76 In sum, international arbitration can have significant impact on sustainable development policies and achievement of the RtD. Whether such arbitration facilitate or undermine the SDGs and the RtD remains context dependent.

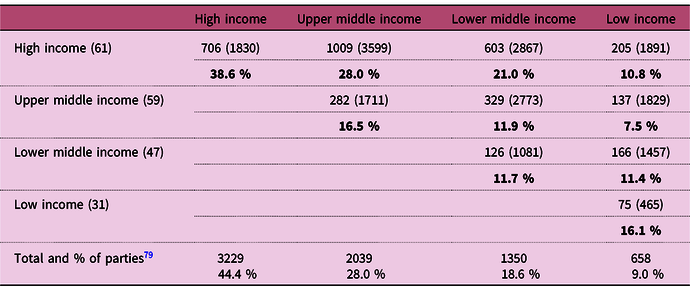

About 85 per cent of IIAs include consent to investor–state arbitration of which almost 11 per cent contain limitations on the scope of arbitration.Footnote 77 However, these numbers say little about the exposure of LDCs or low-income countries to arbitration. In order to get numbers that are more relevant, we must take into account that some IIAs are multilateral and therefore establish more extensive exposure to arbitration than bilateral treaties. Moreover, since many IIAs are overlapping, we also need to adjust the numbers by counting bilateral consent to arbitration only once for each pair of countries. Based on data from UNCTAD, Table 1 shows the exposure to arbitration based on World Bank income groups.

Table 1. Treaty-based bilateral arbitration relationships by World Bank income groups Footnote 78

The entries of Table 1 list: (i) The number of arbitration relationships; (ii) The potential number of arbitration relationships (within parentheses); and (iii) The saturation of arbitration relationships (in bold). Based on 198 potential treaty parties (the number of countries or economies that have signed IIAs to date), the highest possible number of arbitration relationships (full saturation) would be 19,503.Footnote Footnote Footnote 80 For IIAs, the number of arbitration relationships is 3,648 – a saturation of 18.7 per cent. The table shows that the lowest saturation is between low-income and upper middle-income countries (7.5 per cent) and high-income countries (10.8 per cent). If we expand our range of developing countries from 31 low-income countries to 47 LDCs, we find that the latter on average have consented to arbitration in relation to 17.4 other countries, which means saturation of 8.8 per cent, i.e., even lower than for low-income countries.

The general picture is consequently that the countries in most need of development have low exposure to international arbitration based on IIAs. It is also clear that their IIAs can serve to promote FDI only to a limited degree. In sum, IIAs and associated exposure to international arbitration have so far most likely had minor effect on access to FDI and limitations of the policy space for countries most in need of sustainable development.

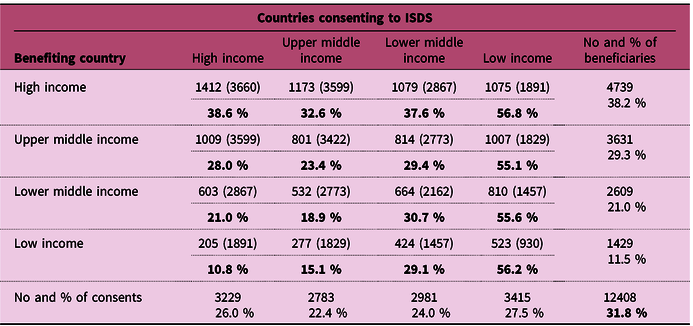

However, the above does not provide the full picture of the exposure of LDCs and low-income countries to international arbitration. For several decades, the World Bank has encouraged and assisted countries in adopting investment legislation that protects foreign investors and provides access to international arbitration.Footnote 81 In contrast to treaty-based consent to arbitration, which is reciprocal, legislation-based consent is unilateral. At least 31 countries have legislation that provides some degree of protection to foreign investors combined with consent to international arbitration. Footnote 82 Such legislation is in force for at least 15 of 31 low-income countries and 15 of 47 LDCs. Table 2 sets out the level of exposure to international arbitration when taking into account consent provided in both IIAs and national investment legislation

Table 2. Investment protection through bilateral and unilateral consent to arbitration Footnote 83

Footnote Since Table 2 includes unilateral consent to arbitration, it distinguishes between states that provide consent to arbitration and states that benefit from such consent (in contrast to Table 1). Table 2 shows the importance of taking into account national legislation when assessing countries’ exposure to international arbitration. When looking at the distribution of consent, it appears that low-income countries have undertaken very high levels of commitments compared to all other income groups – more than 55 per cent on average. Moreover, the percentage of benefiting low-income countries is much lower than any other income group. While low-income countries score highest regarding share of commitments undertaken (27.5 per cent), they score significantly lower in terms of benefiting from the commitments of others (11.5 per cent). One reason why LDCs and low-income countries have low exposure to international arbitration through IIAs may be their extensive consent to investor–state arbitration through domestic legislation, since other countries are less interested in mutual consent when they already have access to unilateral consent.

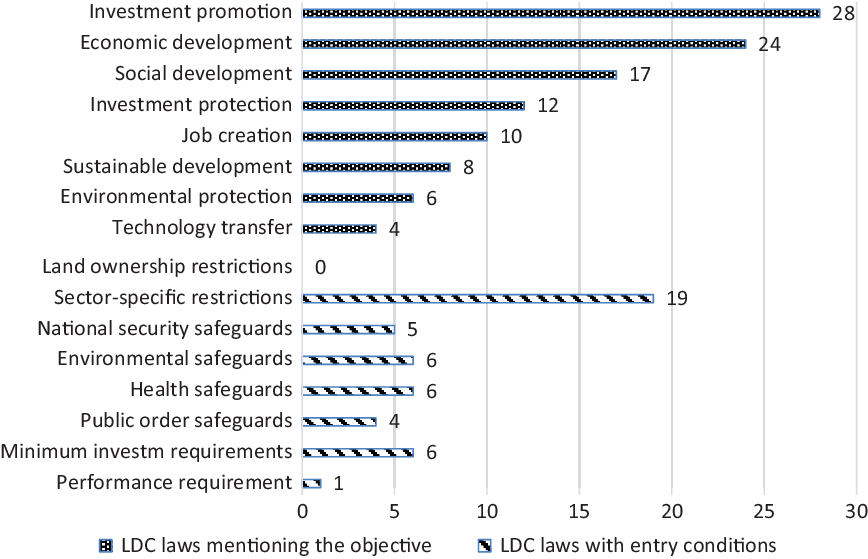

If we look closer at key features of the legislation adopted by LDCs, we see that sustainable development aspects have received limited attention. According to a survey of investment legislation by UNCTAD, the most frequently cited objectives of LDC investment laws are investment promotion, economic development, and social development, while the least frequently cited objectives are technology transfer, environmental protection, and sustainable development (Figure 2). Moreover, there are very few such laws that contain entry conditions (performance requirements and minimum investment requirements). There is a much higher frequency of provisions that authorize public authorities to restrict entry (security, environmental, health and public order safeguards, as well as land ownership and sector-specific restrictions). Further research is needed in order to map the level of protection afforded to foreign investors under investment laws.Footnote 84

Figure 2. Stated objectives and entry conditions in LDC investment laws (N=42)Footnote 85.

In sum, we have found that LDCs and low-income countries have low exposure to international arbitration through IIAs and high exposure through investment legislation. Moreover, investment laws of LDCs seem in general to be more attentive to sustainable development issues than IIAs (compare Figure 1).

3.3 The role of international investment law in promoting the RtD and SDGs

Footnote The tension between two key competing interests associated with investment protection – investors’ interest in low levels of risk, and host countries’ interest in political flexibility – is expressed clearly in UNCTAD’s Core Principles.Footnote 86 However, the Principles fail to make clear how countries should prioritize the conflicting interests. Since the relevant stakeholder interests within host countries vary significantly from country to country and between sectors, it is challenging to establish general guidance on the balancing of investor and host country interests. Nevertheless, this is exactly what IIAs do – they define the conditions under which the interests of foreign investors prevail by determining when host countries must pay compensation if they overrule such interests. Despite decades of criticism and reform proposals,Footnote 87 IIAs remain a tool that restricts host countries’ policy space in favour of foreign investors without defining responsibilities of investors and their home countries.Footnote 88 Together with scant emphasis on the responsibilities of investors’ home states regarding SDGs and the resistance of many developed countries against undertaking commitments in the context of the RtD, IIAs reinforce a general trend towards placing the burden of implementing the RtD on capital importing countries. The draft Convention on the Right to Development can be perceived as an attempt at redressing these concerns.

On the other hand, the limited exposure of LDCs and low-income countries to IIAs with consent to investor – state arbitration indicates that the effect of international investment law has been limited. Consequently, IIAs are unlikely to have had important restrictive effects on the policy space of LDCs and low-income countries. They are also unlikely to have generated significant foreign investment into sustainable development-related sectors.

At first glance, therefore, investment legislation seems to limit the policy space of developing countries more than IIAs. However, it is generally easier for host countries to amend legislation than IIAs, and LDCs may consequently expand their policy space more easily by amending investment legislation than by renegotiating or withdrawing from IIAs. Moreover, restrictions on retroactive legislation may prevent host countries from withdrawing or limiting protection of existing FDI.

Both IIAs and investment legislation increase the bargaining power of foreign investors when negotiating to resolve investment disputes with developing countries. As conditions set out in contracts and concessions that generally are confidential are important to such negotiations, and the results of such negotiations generally are confidential, there has been very limited empirical research on how IIAs and investment legislation affect bargaining power. Nevertheless, such effects are most likely significant, and (international) investment law reform initiatives need to consider them.

Against this background, there might be an important potential for international investment law to promote foreign investment for development purposes. However, the findings above regarding design of IIAs and effects of international arbitration indicate that positive effects for sustainable development are unlikely under the current paradigm of international investment law. Moreover, the emerging trends to broaden the policy space of host countries and attribute responsibility to foreign investors and their home states are weak and slow. The current dominance of investment legislation as a basis for protection and access to international arbitration in LDCs and low-income countries is likely to remain, and perhaps even be reinforced, if IIAs become weaker tools for the protection of foreign investor interests.

We therefore need to pay attention to the potential effects of reform initiatives that may reduce the level of protection of FDI. Such initiatives are likely to enhance demand for protection of investors’ interests through contracts and associated international commercial arbitration. Contractual protection is largely a ‘black box’ to researchers and policy makers due to confidentiality. Lack of transparency facilitates practices that pay limited attention to sustainable development and the RtD. In sum, if international investment law is to become a more forceful tool in support of the RtD, reform initiatives should not move forward without taking into account the dynamics between the three modes investment protection; IIAs, investment legislation, and contracts.

4. The flow of FDI

While the previous section touched upon the indirect impacts of IIAs and investment legislation on flow of FDI through protection of stocks of FDI, this section will consider direct impact through provisions that target the flow of FDI. Such provisions establish right of establishment for foreign investors or prohibitions against restrictions on the flow of FDI.

In general, IIAs do not establish any rights of investors to establish in host countries. Many IIAs contain provisions that call for investment promotion activities. Such provisions are normally aspirational, but sometimes they include institutional and procedural mechanisms that effectively facilitate FDI flows (e.g., consultation committees or investment facilitation authorities).Footnote 89 Approximately 14.5 per cent of IIAs contain investment promotion clauses, of which only one in seven are signed with LDCs.Footnote 90

Prohibitions against restrictions on flows of FDI are sometimes included in IIAs in the form of non-discrimination clauses prohibiting less favourable treatment of foreign than domestic investors (national treatment). National treatment clauses, which are included in almost all IIAs, only prohibit restrictions on flow of FDI if they apply before the investment has been established (pre-establishment). Such provisions prohibit public authorities from imposing more burdensome establishment conditions on foreign than domestic investors. Only approximately 8 per cent of IIAs include such provisions, and LDCs are parties to only one in five of these.Footnote 91 Moreover, since remedies for violation of such provisions are limited to compensation for economic loss, investors can only expect compensation for costs incurred in preparing for the investment. Therefore, host countries can, in most cases, intervene in the pre-establishment phase at low risk.

Some IIAs contain clauses that prohibit performance requirements, sometimes including requirements to be met when establishing an investment. Examples are requirements that the investor use local workers or contribute technology. Such performance requirements can be particularly useful for countries in need of economic development, for example, by ensuring access to and distribution of benefits from FDI. Prohibitions on performance requirements are relatively rare; they are present in approximately 10 per cent of IIAs, of which only one in eight involve LDCs.Footnote 92

Accordingly, IIAs have operationalized investors’ rights to establish in other countries only to a limited extent. Moreover, the low number of relevant provisions that apply to a limited range of LDCs indicates that countries have not been willing to use IIAs to increase the flow of FDI into such countries. Countries need flexibility to adjust FDI incentives and regulation according to changing needs. This is in particular so for LDCs and low-income countries that experience significant variation in conditions. Moving in the direction of increased use of IIAs would be challenging from a policy space perspective, since IIAs may be hard to renegotiate in cases of changed circumstances and some IIAs prevent countries from applying amendments retroactively.

Alternatively, LDCs can implement a right to establishment through investment legislation. According to UNCTAD’s survey of investment laws, only four of 42 LDC investment laws contain clauses regarding freedom of establishment.Footnote 93 As shown in Figure 2, more LDCs impose restrictions on flows of FDI through requirements upon establishment (7), sector-specific restrictions on the entry of FDI (19), and authorizing public authorities to deny entry based on public policy priorities (7).

The World Bank has had a key role in relation to LDC investment legislation through its long-term program to improve developing countries ‘investment climate’. In particular, it has provided country-by-country advice through its Facility for Investment Climate Advisory Services since 1985Footnote 94 and issued guidelines in 1992 and a handbook in 2010.Footnote 95 In recent years, UNCTAD has emerged as an important actor by focusing more extensively on domestic investment legislation and providing country-by-country advice, in particular through its Investment Policy Review program established in 1999.Footnote 96

The current design of investment laws shows that they are used for development purposes, but also that there is significant potential for more effective use of legislation for such purposes. The current use of confidential contracts and associated non-transparent public decision-making raise significant problems, for example related to corruption and conflict of interests.Footnote 97 To the extent that investment legislation can improve the framework for entry of investment and increase transparency and participation in related decision-making, such legislation has the potential of making an important contribution to the RtD. IIAs are less likely to play any significant role in this regard, but their potential for improving communication and co-ordination between investors’ home and host countries could make an important contribution to the RtD.

5. Responsibility of foreign investors

The responsibility of foreign investors can be seen from two main perspectives. From a host country perspective, the main question is how it can ensure that investors repair damage and pay compensation to victims of harmful acts and omissions. Such questions typically arise where investors have sold or abandoned their investments. From the perspective of foreign investors, challenges occur due to their vulnerability to public authorities’ (ab)use of power. Investors are particularly vulnerable when their investments are long-term, capital intensive, and hard to transfer out of the country or to other investors.

Generally, IIAs do not impose duties on investors or their home countries. Nevertheless, as is demonstrated by the draft Convention on the Right to Development, there are some trends in international norms and institutions towards acknowledging responsibility and liability of foreign investors and home countries.Footnote 98 These developments build on a reckoning that host countries may not be able or willing to enforce responsibility or liability of foreign investors for harm caused to third party interests. In the following, we shall look closer at two FDI-related fields; the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, and a regime to address human rights abuses in a transnational context.

The main general mechanism to engage with the responsibility of foreign investors in specific cases is the OECD Guidelines and their associated National Contact Points for Responsible Business Conduct.Footnote 99 The Guidelines date back to 1976 and cover 48 countries. The Guidelines make clear that their observance by enterprises is ‘voluntary and not legally enforceable.’ Home countries undertake to ‘encourage’ their enterprises ‘to observe the Guidelines wherever they operate, while taking into account the particular circumstances of each host country.’ The National Contact Points are to ‘act as a forum for discussion of all matters relating to the Guidelines’.Footnote 100 The Guidelines thereby establish a country-by-country follow-up mechanism that potentially can function as a third party assessment of compliance with the Guidelines. The extent to which National Contact Points in reality fulfil such a function varies significantly among home countries.Footnote 101

The OECD Investment Committee, which has the task of following up on the implementation of the Guidelines, ‘shall not reach conclusions on the conduct of individual enterprises’.Footnote 102 The OECD has established a Database of Specific Instances, which lists 465 cases initiated before National Contact Points during the period 2000–2020.Footnote 103 Approximately 16 per cent of the cases involves a small group of LDCs.Footnote 104 The most important sectors addressed are mining and quarrying, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade – sectors of importance to the RtD and SDGs.Footnote 105

The Guidelines have significant potential to contribute to home countries’ engagement with the responsibility of foreign investors in cases involving harm to LDCs and other developing countries. So far, the practical contribution seems to be limited, and very few IIAs refer to the Guidelines despite the close links that have existed between the Guidelines and the emergence of IIAs.Footnote 106 Current debates concerning the legitimacy of international investment law and associated negotiations in UNCITRALFootnote 107 and UNCTAD initiativesFootnote 108 might provide opportunities to enhance the status and effect of the Guidelines as a means to support the RtD and SDGs.

Based on the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, The UN Human Rights Council and the High Commissioner for Human Rights have initiated three tracks of particular interest to the responsibility of foreign investors.Footnote 109 These initiatives refer to the International Bill of Human RightsFootnote 110 as well as the eight ILO Core Conventions as set out in the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (Guiding Principle no. 12). They are therefore highly relevant to the RtD and a broad range of SDGs.

The first track is follow-up of the Guiding Principles by the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, established in 2011.Footnote 111 One of the tasks is to ‘explore options and make recommendations at the national, regional and international levels for enhancing access to effective remedies available to those whose human rights are affected by corporate activities’.Footnote 112 The Guiding Principles are weak in terms of specific obligations to ensure effective access to remedies where harm has been caused through activities funded by FDI (see principles 26, 27 and 31). When renewing the mandate of the Working Group in both 2014 and 2017, the Human Rights Council expressed concern about the:

legal and practical barriers to remedies for business-related human rights abuses, which may leave those aggrieved without opportunity for effective remedy, including through judicial and non-judicial avenues, and recognizing that it may be further considered whether relevant legal frameworks would provide more effective avenues of remedy for affected individuals and communities.Footnote 113

The Working Group’s follow-up regarding access to effective remedies is a central topic in resolutions of the Human Rights Council and focuses increasingly on ‘cross-border cases’.Footnote 114 However, the Working Group initiatives have so far had limited results in terms of improved access to remedies in cases involving foreign investors.

The second track started in 2014 with the establishment of an ‘open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights’ whose task is to elaborate an ‘international legally binding instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights’.Footnote 115 At its fifth session in 2019, the working group carried out its first substantive negotiations based on a draft instrument.Footnote 116 Article 6 proposes rules on ‘legal liability’ and establishes the following starting points:

1. State Parties shall ensure that their domestic law provides for a comprehensive and adequate system of legal liability for human rights violations or abuses in the context of business activities, including those of transnational character …

4. States Parties shall adopt legal and other measures necessary to ensure that their domestic jurisdiction provides for effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions and reparations to the benefit of the victims where business activities, including those of transnational character, have caused harm to victims.

In addition, the draft proposes detailed rules on ‘mutual legal assistance’ in individual cases and to establish an ‘International Fund for Victims’. An initial proposal to establish National Implementation Mechanisms, similar to the National Contact Points of the OECD Guidelines, has been omitted in the revised draft. The instrument is still, more than five years after the establishment of the working group, in an early phase of development.

The High Commissioner for Human Rights initiated the third track – the Accountability and Remedy Project – in 2014.Footnote 117 The first phase of this project aims at enhancing the effectiveness of judicial mechanisms in cases of business-related human rights abuse. The final report, which seeks to provide countries with practical advice on how to design and implement accountability mechanisms in the domestic context, was submitted to the Human Rights Council in 2016.Footnote 118

In sum, we see that the OECD and key UN human rights institutions pay attention to the availability of formalized and transparent remedies to address human rights violations in the context of FDI. This is a sign that there may be increasing support for provisions on investor responsibility also in the negotiations of the Convention on the Right to Development. So far, there has been very limited support for provisions on investor or home state responsibility in IIAs. The progress made in the OECD and UN human rights process in this direction has been very slow, and countries, in particular capital exporting, do not seem to gather behind proposals to establish judicial remedies. Nevertheless, the ‘legitimacy crisis’ and reform initiatives within international investment law may possibly lead to increased interest in (re)considering such issues also in the context of IIAs.

6. Conclusions

While there seems to be broad agreement that FDI is very important to realize the RtD and achieve the SDGs, there are many unresolved questions concerning how to proceed to achieve synergies. On a general level, we have found that the legal framework for promotion and protection of FDI relies heavily on limiting the policy space available to host countries when elaborating measures to respect, protect and fulfil the RtD and achieve SDGs. This contribution shows that countries have been relatively unsuccessful in establishing domestic and international rules regarding duties and responsibility of foreign investors and their home countries. In other words, while international law remains dependent on the willingness and ability of host countries to take measures to respect, protect and fulfil the RtD, international investment law remains focused on protecting investors’ rights by limiting the policy space of host countries.

Interestingly, however, international investment law remains essentially insignificant for investors and investment that target countries in most need of development – the LCDs and low-income countries. One reason is foreign investors’ ability to achieve protection through investment laws and contracts. One key question is therefore whether enhanced resort to IIAs and treaty-based arbitration can be a better option for LDCs and low-income countries than their current reliance on investment laws, contracts and the associated international commercial arbitration as means to attract and retain beneficial FDI. While international investment law has taken steps in the direction of lower formal restrictions on host countries’ policy space, little is known about the less visible informal effects of treaty-based protection during consultations and negotiation between investors and host countries. Moreover, international investment law has not yet engaged significantly with the duties and responsibility of investors and their home countries. Unless international investment law allows sufficient policy space and engages with relevant duties and responsibility, it is likely to remain marginal to LDCs’ and low-income countries’ efforts to realize the RtD and achieve SDGs.

One key reason why international investment law could be an attractive alternative to investment legislation, contracts and international commercial arbitration, is the level of transparency and scrutiny as well as the potential engagement of the investors’ home countries that follows with investment treaty arbitration. In addition, some IIAs establish diplomatic mechanisms between host and home countries for discussion of investment related issues. Against this background, a dilemma emerges. If international investment law reforms provide broader policy space and engage the duties and responsibility of investors, investors are likely to look elsewhere to find protection for their investments in LDCs and low-income countries. Such reforms are therefore likely to enhance the use of investment legislation and contracts for such purposes.

Some will argue that IIAs and associated arbitration suffer from lack of transparency and high dispute settlement costs, and that they therefore are unattractive as tools to attract and retain FDI. Investment legislation and contracts suffer from similar challenges. A third alternative for investors is to seek protection through investment guarantees and similar support schemes set up by their home countries. Such schemes have been used for a long time, and can be adjusted to provide improved support to the RtD and SDGs in host countries. However, they are likely to remain dominated by home countries’ policy priorities and cannot fully cover the need for FDI in LDCs and low-income countries.

In conclusion, there might be an important role for international investment law in terms of enhancing the ability of LDCs and low-income countries to realize the RtD and achieve SDGs. One important strategy to resolve the above dilemma can be to seek general agreement among LDCs and low-income countries to reform investment legislation and contractual practice so that these modes of investment protection do not undermine the role of international investment law. Unless this can be done, the potential for international investment law to contribute significantly to the RtD and SDGs is likely to remain marginal.