1. Introduction

The structure of the global governance system has undergone significant changes in the past few years. From a system governed primarily by global public law institutions (GPLIs) established through multilateral treaties, it has metamorphosed into a hybrid field in which a plethora of public, private, and semi-public institutions interact in various ways. In this new universe, private transnational regulatory regimes (PTRs) have assumed a key governance role.Footnote 1 The new PTRs operate in diverse areas, ranging from product standards and environmental protection to financial reporting, human and labour rights, and the ranking of academic institutions.Footnote 2 Most of these PTRs include both a normative facet – a set of prescriptive behavioural guidelines usually focusing on firms – and an institutional framework with a compliance functionality. I use the term ‘PTR’ to refer to the institutional complex that includes the relevant legal texts, the body (or bodies) responsible for administering the texts, and the individual agents closely associated with these bodies. PTRs may encompass more than one organization, as for example, when the compliance functionality is not provided by the body responsible for developing the norms.

The emergence of PTRs as important actors in the global governance domain reflects the weakness of the international treaty system, which is finding it increasingly difficult cope with global crises such as climate change or the corona pandemic.Footnote 3 Two features of the treaty system contribute to this regulatory gap: its dependence on the consensual action of governments and its rigid bureaucratic structure. Together, the two features have undermined the capacity of the treaty system to produce common policies and to respond effectively to global risks.Footnote 4

The increasing prominence of PTRs in the governance of global affairs presents a complex challenge to legal and political theory. In the present article, I respond to this challenge by developing a network-driven model of transnational legal authority, which challenges contemporary thinking about global authority. I argue that transnational legal authority is an emergent, network-based phenomenon. The framework I propose brings together ideas from network science, legal theory, and social sciences. I explore the structural and dynamic conditions that can lead to the emergence of transnational network authority. I link this argument to the concept of multi-layered networks and develop an analytical framework that explains how multi-layered networks are realized in the transnational context. Building on the concept of multi-layered networks, I show how transnational legal authority can arise through the synergistic interaction between network nodes. According to this account, the authority of PTRs is an emergent feature of the networks in which they are embedded. I examine the linkage between the sociological and the jurisprudential aspects of the authority of PTRs. I develop the idea of ‘network grounding’, which challenges the orthodox view regarding the legal nature of PTRs. Network grounding brings to the fore the question of the inherently paradoxical nature of law. I conclude the discussion of network grounding by offering a potential resolution to this intrinsic paradox, as it is manifested in the transnational arena.

I argue that the network model has several advantages over existing models of transnational law. First, the model ties together sociological and jurisprudential analysis of transnational regulatory networks. Second, it allows us to distinguish between constitutionalized systems, systems of pure regulatory power (lacking a constitutional dimension), and lawless private governance structures. Third, the network model provides a better understanding of the steering capacities of PTRs and of how they can complement the work of both treaty-based organizations and state-based regulatory agencies.

The social network approach, which plays a key role in my argument, is driven by the idea that the patterning of social ties in which actors are embedded has important consequences for the dynamics of social systems.Footnote 5 Social network analysis (SNA) captures this pattern by representing the social system as an abstract structure of nodes and edges, which can depict different kinds of entities and interactions. The entities studied by network science include cells, individuals, organizations, or texts; the interactions include information flow, trade, friendship, citations, and more. Scientists in a range of fields have developed an extensive set of tools for analysing the structure and dynamics of networks.Footnote 6

The article proceeds as follows. In Section 2, I discuss the lacunae in the literature on private transnational governance. In Section 3, I introduce the model of transnational networked authority. In Section 4, I discuss the legal-doctrinal implications of the model. I conclude the article, in Section 5, with a discussion of the policy implications of my argument and by highlighting further directions for research.

2. Networks and private transnational governance: A review and critique of the literature

A key aspect of the model of transnational networked authority is the claim that the authority of PTRs is fundamentally relational, and that this relational aspect is critical for understanding how legal authority evolves beyond the state. This idea distinguishes the network model from other theoretical approaches that regard the authority of PTRs as based on either formal delegation or on completely endogenous processes of self-grounding.Footnote 7

The role of networks in global governance has been studied from various perspectives, ranging from law to political science and business management.Footnote 8 The current literature, however, does not offer an account of the role that networks may play in the evolution of transnational legal authority. There has been no attempt to explore the linkage between the jurisprudential underpinnings of transnational law and its network structure, either at the level of theory building (bringing together ideas from philosophy of law and network theory) or of empirical analysis (studying how this linkage is manifested in concrete PTR networks).

The discussion of the linkage between transnational networks and private authority has tended to be extremely vague and underspecified. For example, in a recent paper, Nico Krisch distinguished between ‘solid’ and ‘liquid’ authority. Solid authority is based on the conventional delegation model and is characterized by ‘legal powers to take binding decisions, a basis in formal delegation, and ideally the ability to use enforcement tools’.Footnote 9 By contrast, liquid authority may be ‘spread out over a process in which it is hard to locate, and which is in constant flux… and is thus more difficult to grasp …’.Footnote 10 Krisch mentioned the connection between liquid authority and networked authority, but did not explore the possibility that networks play a special role in the establishment of transnational authority.Footnote 11 The linkage between the ideas of liquid and networked authority remains underspecified.

The argument I develop in this article has some affinity with the work of Roughan and Halpin on pluralist jurisprudence.Footnote 12 The model of networked authority can be interpreted as one potential manifestation of pluralist jurisprudence, but Roughan and Halpin did not explore the potential linkage between network theory and pluralist jurisprudence.Footnote 13 There is an implicit reference to the idea of networked authority in Ralf Michaels’ chapter, which argues that a necessary consequence of global legal pluralism is a relational concept of law.Footnote 14 Michaels, however, does not articulate the exact socio-legal mechanisms through which relational legality is realized, nor does he explore the linkage between this idea and network theory.

Culver and Guidice’s recent work on the borders of legality also seeks to develop a relational understanding of law.Footnote 15 They emphasize the importance of institutional interdependence for understanding the law:Footnote 16

[I]t is useful to choose, as legality-tracking characteristics of legal institutions interacting over time, the fact that those institutions are typically part of a composition of inter-dependent institutions related by mutual reference occurring at some level of intensity.

Although Culver and Giudice noted that their ‘inter-institutional approach owes something to network theory,’Footnote 17 they avoided using network analysis as part of their jurisprudential model.Footnote 18 Their primary critique of network analysis is that it:

[r]elies for its probative value on the prior availability of the prediction or organizational mandate against which it is contrasted, and that departure point embodies a particular conception of the network of actors under analysis. The trouble with social network analysis then, is that its responsiveness to phenomena comes at the cost of the need for prior (even if revisable) demarcation of relevant data for analysis …Footnote 19

I find this objection unconvincing. First, Culver and Giudice’s approach is self-contradictory. There is a tension between the conceptual narrative of the text, which draws extensively on network-related notions (e.g., interdependence, mutual reference),Footnote 20 and the authors’ stated opposition to SNA. This tension raises doubts about the theoretical robustness of their critique. Second, the critique of SNA is problematic. Most important, it reflects a misapprehension of the capacity of SNA to detect patterns in unordered data (e.g., through community detection techniques), and to model the dynamic of networks (e.g., through such models as preferential attachment).Footnote 21

In a series of articles, Stepan Wood, Burkard Eberlein, and their collaborators have studied the role of interactions in transnational business governance. They defined interactions as ‘mutual actions and responses of individuals, groups, institutions or systems’,Footnote 22 and transnational governance as ‘governance in which non-state actors or institutions assert or exercise authority in the performance of one or more components of regulatory governance across national borders’.Footnote 23 They then developed an analytical framework to study the nexus between dimensions of interaction (e.g., who interacts, and the pathways and character of the interaction) and components of regulatory governance (e.g., rule formation, monitoring, and compliance).Footnote 24

The framework of transnational business governance interactions (TBGI) has many affinities with the argument of this article, but it leaves many questions open. First, although TBGI is interested in the exercise of authority, its theoretical apparatus does not explain how such authority arises through the interactive dynamics of transnational regulation. Second, the various papers that appeared as part of the TBGI project, do not address the jurisprudential question regarding the (legal) nature of different transnational normative orders.Footnote 25 Finally, the broad interpretation adopted by the TBGI project to the concept of interaction limits its explanatory power.Footnote 26 Wood et al. responded to this critique by noting that refinement of the concept can take place at the stage of operationalization, but this response does not resolve the fundamental difficulty with the concept.Footnote 27 In the present article, I seek to fill this theoretical gap both by answering the questions Wood et al. have left open and by developing a more refined theoretical framework of transnational interactions that is embedded in a network framework.

The idea of networked governance was explored also by political scientists, most notably, by Anne-Marie Slaughter,Footnote 28 Diane Stone,Footnote 29 and Miles Kahler.Footnote 30 In a recent book, The Chessboard and the Web: Strategies of Connection in a Networked World, Slaughter included an entire chapter on ‘Network Power’,Footnote 31 but did not examine whether the increasing normative influence of non-state private legal regimes can be explained by reference to the configuration of the network in which they are embedded. Stone studied the role of global public policy networks (GPPN) in the diffusion of policy ideas, and has argued that their authority is based on pooling of authority, but has not attempted to disentangle the exact network processes by which this pooling takes place.Footnote 32 Kahler distinguished between two approaches to network analysis of international politics: networks as structures that influence the behaviour of network members, and networks as autonomous agents.Footnote 33 But Kahler did not explore the possibility that the interaction between structure and agency can lead to a new form of transnational authority, which is the thesis of the present article. All these accounts have added to our understanding of the role of networks in international interactions, but they stopped short of developing an explicit account of the constitutive role of networks in the foundation of transnational authority, and of the exact institutional pathways by which this role is played out, leaving a gap in the analysis of networks in global governance.Footnote 34

3. Fundamentals of networked authority

The model of transnational networked authority addresses the gaps in the literature by offering a new way of thinking about the consolidation of legal authority at the transnational level. The model is based on the following thesis: the emergence of global networked authority is dependent on the existence of a multi-layered structure of strongly connected transnational regimes.Footnote 35 In a multi-layered network, actors (nodes) are connected through multiple types of socially relevant ties.Footnote 36 According to this model, transnational legal authority evolves only when the multi-layered network satisfies certain conditions related to its topology (density and cross-layer coherence) and dynamics (intensity of the social interactions within and across layers), which jointly create a synergistic effect. Footnote 37 Key factors in the emergence of networked authority are the normative and compliance synergies that emerge through the densification of links across the different layers.

Under certain conditions, the multi-layered structure of a network of PTRs can facilitate the emergence of a self-organized legal system with the following features:

-

1. Each member (regime) of the PTR network constitutes an independent legal system that exerts authority through its associated normative texts and overarching organizational body. Each regime thus forms an independent locus of legal power.

-

2. The PTR network has the features of a self-organized system: its overall pattern and dynamics are self-generated and not externally controlled.Footnote 38

-

3. The PTR network provides the conditions of reflexivity required for the emergence of a constitutionalized system.

-

4. The realization of (a) to (c) does not depend on the network becoming an independent legal actor in itself, although this is a possible consequence.

I argue that transnational legal authority should be viewed as an emergent, network-based phenomenon.Footnote 39 Drawing on Wilensky and Rand, I define emergence as ‘the arising of novel and coherent structures, patterns, and properties through the interactions of multiple distributed elements’.Footnote 40 A distinctive feature of emergent structures is that their properties cannot be deduced from the properties of the elements alone, but arise also from interactions between the elements.Footnote 41 Another important feature of emergent phenomena is the existence of synergy,Footnote 42 which refers to the ‘combined or cooperative effects produced by the relationships between various forces, particles, elements, parts or individuals in a given context—effects that are not otherwise attainable’.Footnote 43 We can distinguish between synergies of scale, which arise ‘from adding (or multiplying) more of the same thing’,Footnote 44 and tend to exhibit threshold effects;Footnote 45 and synergies that arise out of functional complementarity and represent a situation in which entities with different properties interact in a way that generates novel beneficial effects.Footnote 46

The challenge facing the model of transnational networked authority is to elaborate its socio-jurisprudential characteristics and to lay bare the structural and dynamic conditions that facilitate its emergence.

3.1 The multi-layered structure of PTR networks

In this section, I elucidate my argument regarding the multi-layered structure of PTR networks and their emergent socio-legal features. To this end, I adopt a dual lens approach that brings together an internal legal perspective with an external sociological one. As I argued above, in a multi-layered network, a common set of actors is connected through multiple types of socially relevant ties. Each of these interaction types can be represented as a different layer of the multi-layered network. In analysing the links between the PTRs, I distinguish between two dimensions: (i) the social type of the interaction and (ii) the topological configuration through which the link between the regimes is realized (in particular, whether the link represents a direct or induced connection). Below I elaborate the structure of the layers that play a key role in the evolution of PTR networks, distinguishing between the type of the interaction and its topological manifestation.

3.1.1 Institutional connections

PTRs can be connected either directly, through various organizational interactions, or indirectly, through joint affiliation with third parties (e.g., joint firms):

-

1. Direct links: four types of direct institutional connections can be distinguished: governance, partnership, compliance cooperation, and membership.

-

1.1 Governance refers to the participation of PTR organizations in the governance of other organizations.

-

1.2 Partnership refers to various forms of collaboration between PTRs.

-

1.3 Compliance cooperation refers to a situation in which some PTR organizations provide traceability or compliance services to other organizations.

-

1.4 Membership refers to the membership of PTR organizationsFootnote 47 in other PTRs.

-

-

2. Affiliation structures: PTRs can be indirectly linked through their joint affiliation with various third parties, such as firms (that are certified by different PTRs), umbrella organizations, such as ISEAL,Footnote 48 or compliance assurance bodies.Footnote 49 The affiliation structure linking PTRs and corporate members can be captured in a bi-partite network, where the first set includes a list of distinct PTRs and the second a list of firms. Such affiliation structures may arise because of overlaps in the regulatory remits of different regimes. In the case of umbrella organizations, such as ISEAL, PTRs are indirectly connected through their co-membership (e.g., ISEAL members include organizations such as Fairtrade International, Forest Stewardship Council, and the Gold Standard).Footnote 50

3.1.2 Citation links between the legal standards associated with the distinct PTRs and between other legal instruments

This layer focuses on the legal texts that undergird the network and the way in which they either cross-reference each other or refer to (or are cited by) external legal texts (which can be international treaties, national legislation, corporate codes, and supply-chain contracts). Henceforth, I refer to these texts as ‘standards’ or ‘codes’.

3.1.3 Relations between individual agents

The PTR organizations can also be linked through direct interactions between individuals working in the organizations that administer the standards. In addition, PTR organizations can become affiliated through their association with the same individual agents (e.g., directors, advisors). With regard to corporate entities, this affiliation structure has been studied in the context of ‘interlocking directorates’.Footnote 51

3.1.4 Shared conceptual architecture

This layer emerges through the common referencing to general legal concepts in PTR standards. Formally, such structures are realized in a bi-partite network, where the first set includes a list of the distinct PTR standards, and the second a list of concepts (e.g., sustainability, gender equality, circular economy).

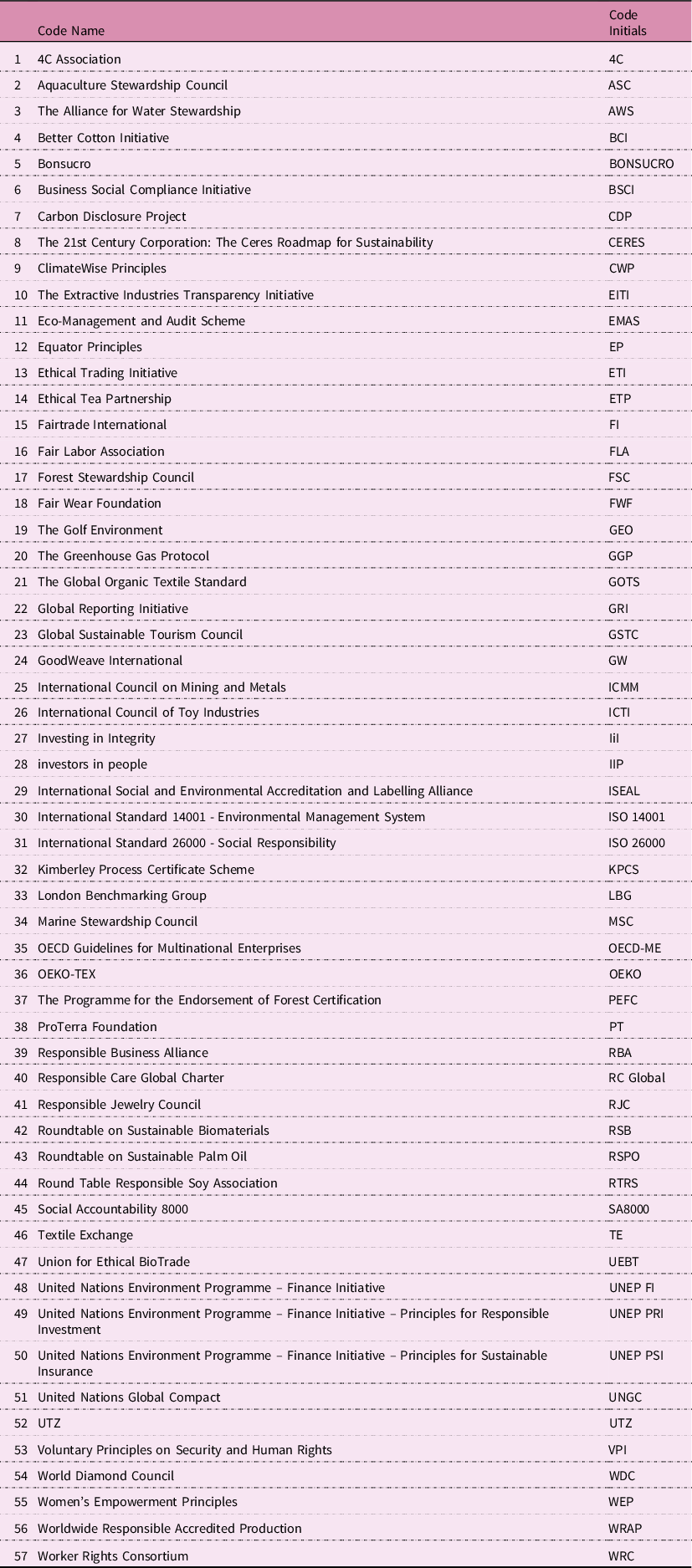

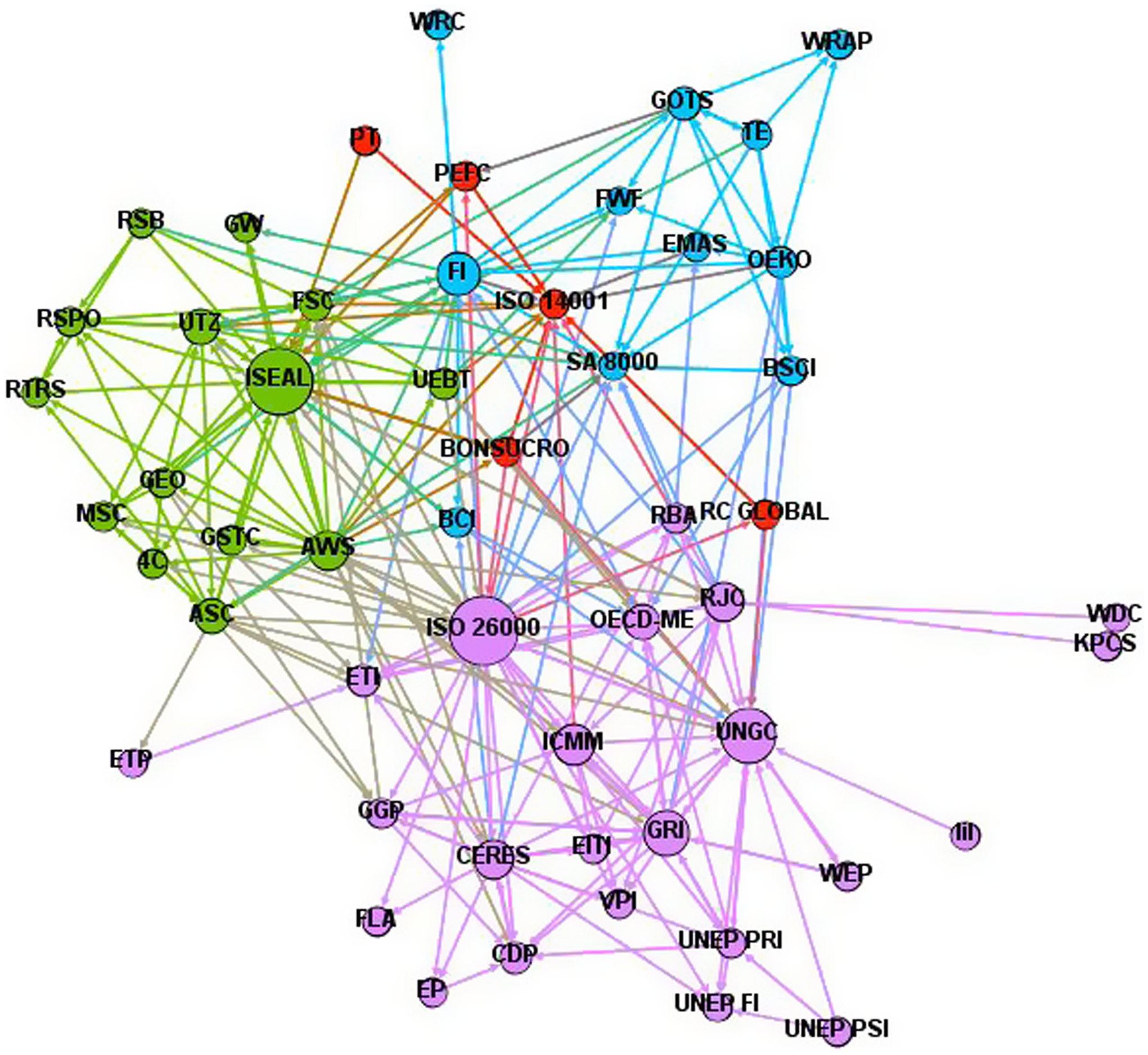

To illustrate how the above framework is manifested in a concrete network, I selected nine CSR schemes, which are part of the sample analysed in detail in Section 3.2 below: Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), UN Global Compact (UNGC), International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), Equator Principles (EP), Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC), Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Council for Responsible Jewelry Practices (RJC), and the global membership association for credible sustainability standards (ISEAL).Footnote 52 I analysed the connections between these schemes across three layers (Figure 1), which represent different types of links between the actors: a layer that describes cross-citations between the standards associated with the schemes; a layer that describes direct organizational ties; and a layer that describes indirect links between the schemes based on their joint association with certified firms.Footnote 53

Figure 1. A snapshot of the CSR system as a multi-layered network.

The multi-layer representation can enrich our understanding of the topology and dynamics of the PTR system in various ways. First, by exposing the extent to which every edge appears in every layer (link overlap), it provides a way to measure the topological coherence of the system. Second, multi-layer analysis can shed light on the informational dynamic of the network by exposing the multiple paths through which information can flow in the PTR system. In the example in Figure 1, the multi-layer perspective demonstrates how information can reach organizations that appear isolated in one layer (e.g., Equator Principles on the Direct Institutional Links layer), but are connected to the rest of the network through other layers (the layer of Induced Institutional Network).Footnote 54 Finally, the multi-layer perspective enables a better understanding of the positional structure of the network by providing a broader view of the centrality of PTRs across layers. In the example above, GRI, UNGC, and CDP emerge as the most central organizations, taking the three layers as a whole.

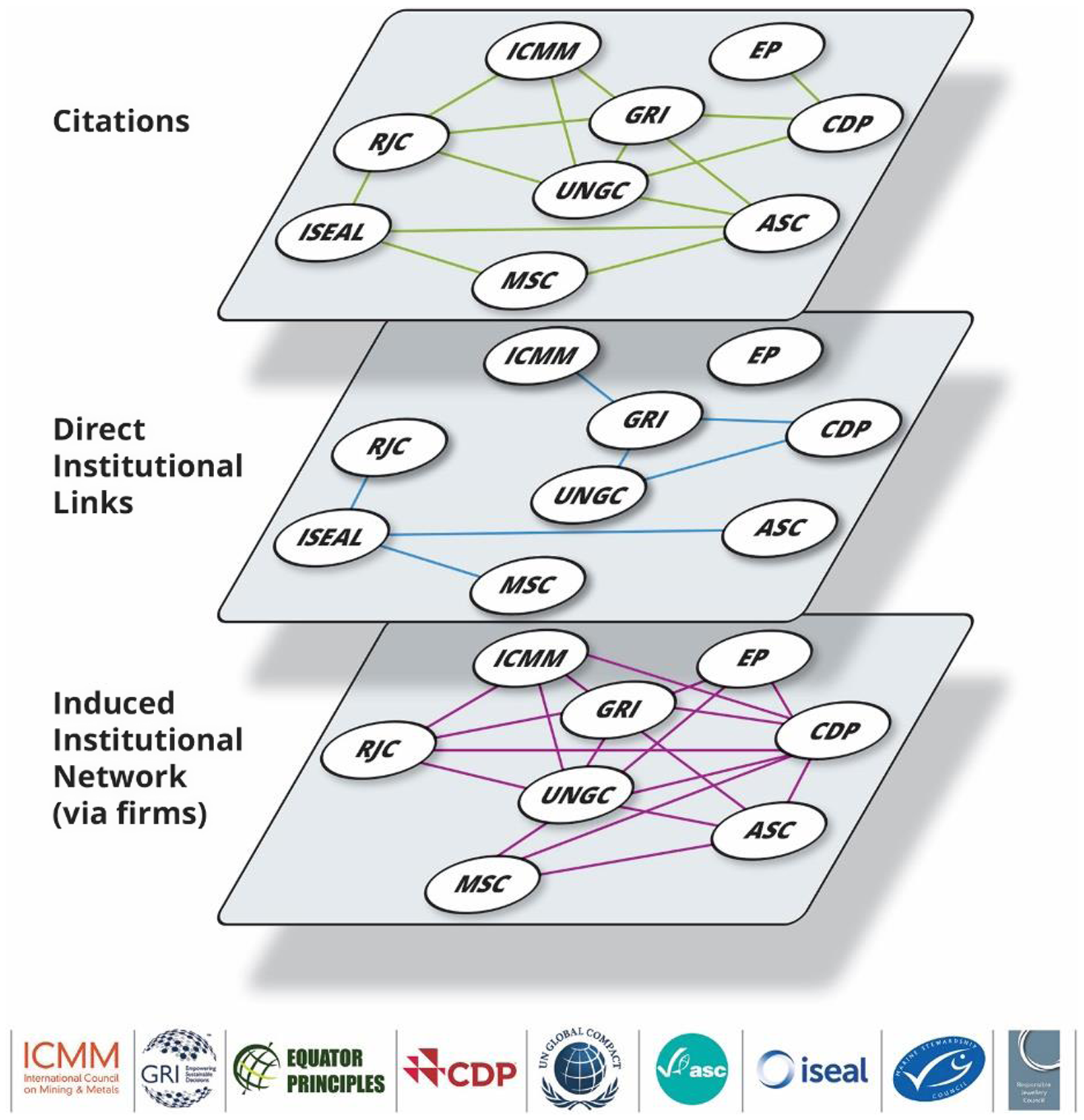

Table 1 elaborates the general framework suggested above through a two-dimensional matrix, where each cell represents a different layer in the multi-layered PTR network. To emphasize the embeddedness of PTR networks in the global governance system, the Table also includes external links, connecting PTRs with entities beyond the PTR network. The way in which PTRs are represented across layers may differ according to the nature of the socio-legal interaction captured by a particular layer. I distinguish between ‘elementary nodes’, which represent the core regime, and ‘layer-specific nodes’, which represent the manifestation of the elementary node in a particular layer (e.g., standards associated with a particular regime, its employees, or an associated organizational body).

Table 1. The multi-layered structure of a PTR network

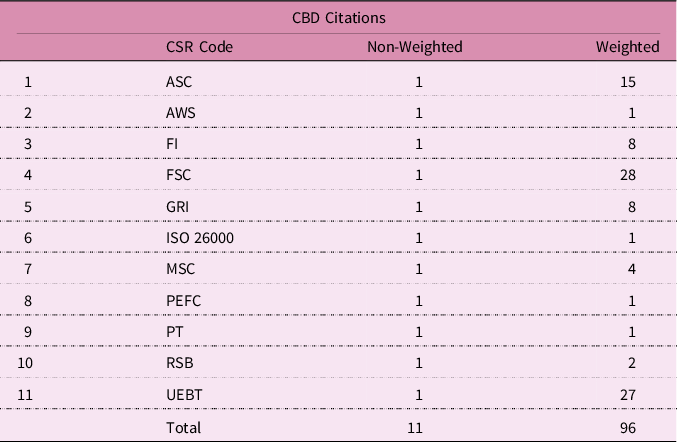

Table 2. References to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity

A multi-layered PTR network can be formally defined by the triple M = (Y, G, F):

Y indicates the set of layers:

G indicates the ordered list of networks and the topological structure of each layer (α = 1, 2 … n), where:

G α is the network in layer α (e.g., the layer of institutional ties). The set of nodes (e.g., PTR organizations) of layer α is indicated by V α, and the set of edges connecting nodes within layer α is indicated by E α. Finally, F is the list of bipartite networks that captures the interactions across pairs of different layers and has elements F α,β given by:

3.2 The emergence of transnational networked authority: Grounding, legitimacy, and steering

In this section, I elaborate how the multi-layered structure described above leads to the emergence of transnational legal authority. I focus on three key questions: (i) What are the network mechanisms that facilitate the emergence of PTRs as independent loci of legal authority and determine the boundaries of the network (in the absence of a central rule of recognition or Grundnorm)?; (ii) What are the unique properties that distinguish a constitutionalized PTR system from other forms of transnational governance?; and (iii) What are the unique features that enable a PTR network to influence its external environment (external steering) even without the backing of the state administrative power? This discussion pulls together the sociological and jurisprudential aspects of the model.

3.2.1 Relational authority and network grounding

The model of transnational networked authority challenges the conventional, pyramidal understanding of the law by developing a relational concept of authority. According to this account, the authority of PTRs is the emergent product of cyclical interactions between the distinct regimes. In the transnational context, there is no ultimate ‘rule of recognition’ that can ascertain which normative text is legal and which is not. Any ‘marking’ of a text as ‘law’ is the outcome of a three-fold, network-embedded process of self-reference, cross-reference, and external reference.

Self-reference or self-authorization is achieved by marking the normative text with terms that have a clear legal connotation, such as ‘standard’ or ‘code’, and by the publication of formal interpretations and guidelines (second-order observation of the legal text).Footnote 55 Cross-reference is the process by which a PTR standard cites another standard. Such citation, understood as a form of legal speech act, serves several goals. First, it is used to support the normative standing, or the validity, of the citing document.Footnote 56 Second, by citing another standard (as a mean of supporting its own validity) the citing standard recognizes (implicitly) the legal validity of the cited text.Footnote 57 The citation operates as a declarative speech act that does not merely acknowledge (or indicate) that the cited normative text has a particular feature (validity), but also constitutes it as such.Footnote 58 Finally, citation as recognition also includes an implicit act of self-recognition, because validating another normative text makes sense only if the citing text also recognizes itself as valid.

Second, by singling-out certain texts (nodes) as relevant to the citing text (and excluding others), citation determines the boundaries of the network. This boundaries-generating function becomes apparent only at the macro level, where nodes that are linked more densely among themselves than with nodes outside the group emerge as a distinct community.Footnote 59

The constitutive aspect of the citation can be realized only if it is embedded in a sufficiently dense structure of cross-citations, reflecting the emergent nature of network authority. The constitutive force of the act of recognition that underlies the cross-citation between two PTRs is therefore contingent upon the overall topology of the network.

The constitutionalization of PTR standards as valid sources of law is also influenced by two forms of external referencing. The first is the citing of international public law instruments (e.g., international treaties) by PTR standards. The second is the citing of PTR standards by national legislation, corporate codes of conduct, or corporate supply-chain contracts. External referencing contributes to the validity of PTRs in several ways. First, citing global treaties enables PTR standards to rely on the validity of recognized sources of legal authority. The direction of this referencing is the inverse of the conventional delegation model: the authority is not bestowed upon the agent lacking it through explicit delegation, but rather is extracted unilaterally through the referential act. Second, the citation of PTR standards in national legislation, corporate codes of conduct, and corporate supply-chain contributes to their validity by identifying them as credible sources of normative content. Finally, external referencing also functions as a boundary-setting mechanism, by implicitly linking together standards that cite and are cited by the same legal instruments.

The relational account of transnational authority challenges two tenets of traditional jurisprudence: hierarchy and well-foundedness.Footnote 60 According to the hierarchy thesis, the validity of legal norms can be derived only from higher-ranked (valid) legal norms. According to the well-foundedness thesis, legal validity must be grounded in some ultimate source; the relation of dependence between legal norms must terminate, according to this thesis, in something fundamental.Footnote 61 The model of network authority departs from the conventional conception of legal authority by claiming that validity and authority can emerge from a non-hierarchical (horizontal) network of cross-references, even when none of the network nodes can be described as foundational (that is, none of the nodes have possessed the property of validity before linking with the other nodes).Footnote 62

A word about my understanding of validity is in order here. Validity provides legal norms with their binding force and distinguishes them from non-legal norms.Footnote 63 The bindingness of legal norms is reflected in their capacity to change the legal entitlements and statuses attributed to a subject.Footnote 64 Another feature of binding norms is their capacity to create content-independent reasons for action.Footnote 65 PTR norms realize these dual aspects of bindingness, both in the internal dynamic of the PTR network, and in their interaction with external public norms.

The concept of grounding is given different meanings in the model of network authority and in the framework of traditional jurisprudence. In the traditional jurisprudential framework, grounding is understood as a noncausal, linear dependence between legal facts and their determinants. This relation of dependence satisfies several logical properties:Footnote 66 irreflexivity – x cannot be a ground of itself; asymmetry – if x is a ground of y, y cannot be a ground of x; transitivity – if x is a ground of y, and y is a ground of z, then x is a ground of z; and well-foundedness, which implies that every non-fundamental entity in the system under consideration is fully grounded by some fundamental (and ungrounded) entity or entities that fully account for its being.Footnote 67 The concept of well-foundedness is based on the intuition that the ‘derivative must have its source in, or acquire its being from, the non-derivative’.Footnote 68

The cyclical and emergent features of network authority give rise to a different understanding of grounding.Footnote 69 Network grounding (grounding N ), is reflexive both because, as elaborated above, the act of external recognition depends on self-recognition and because code x may appear in its own grounding ancestry, owing to the potentially cyclic structure of network grounding. Grounding N is also weakly symmetric, that is, code x may be a ground N of code y and y a ground N of x. Thus, both x and y may appear in the grounding ancestry of each other.Footnote 70 Grounding N is also transitive, that is, from the fact that code x recognizes y, and y recognizes z, we can deduce that x is a ground N of z.Footnote 71 Grounding N does not satisfy the well-foundedness criterion, that is, the dependence chains that are established through cross-references between the PTRs do not terminate in a node that is presumed to be fundamental in any way.Footnote 72 Furthermore, any code in the network can participate in multiple grounding chains. Finally, grounding N is also contingent in the sense that its constitutive potential is realized only if it is embedded in a sufficiently dense structure of cross-citations, reflecting the emergent nature of network authority.

The idea of network grounding involves, however, a deep-seated paradox, whose structure resembles that of the truth-teller paradox. The truth-teller paradox deals with sentences, such as: ‘(K) Sentence K is true’. The problem with truth-teller sentences is their indeterminacy.Footnote 73 Note that this paradox emerges also in the context of national legal systems. The idea that the validity of lower-level norms can be derived only from higher-level norms leaves us with the puzzle of how to explain the validity of the ultimate norm of the land (usually, the constitution). Frederick Schauer has neatly articulated this puzzle:Footnote 74

We know that laws are made valid by other laws, and those other laws by still other laws, and so on, until we run out of laws. But what determines the validity of the highest law? What keeps the entire structure from collapsing? On what does the validity of an entire legal system rest?

Legal theorists have developed various responses to this conundrum, ranging from H. L. A. Hart’s rule of recognition, whose validity rests on the brute fact of social acceptance, to Hans Kelsen’s interpretation of the Grundnorm as a ‘transcendental-logical presupposition’.Footnote 75

The distinction between the transnational and the national systems thus comes down to a difference in their strategies of de-paradoxification, that is, in the mechanisms that make the illogicality that underlies them tolerable. At the national level, the paradox of the foundation of law has been suppressed through an appeal to a mythical constitutional moment.Footnote 76 At the transnational level, this strategy is rarely used. Rather, the paradox is suppressed by embedding it in dense chains of grounding links. De-pardoxification is achieved through the evolution of multiple cycles of validation, which conceal the paradox, and make the idea of network grounding both coherent and intelligible. This epistemic and sociological tolerance is an emergent property of the network.

3.2.2 Network cross-referentiality in action

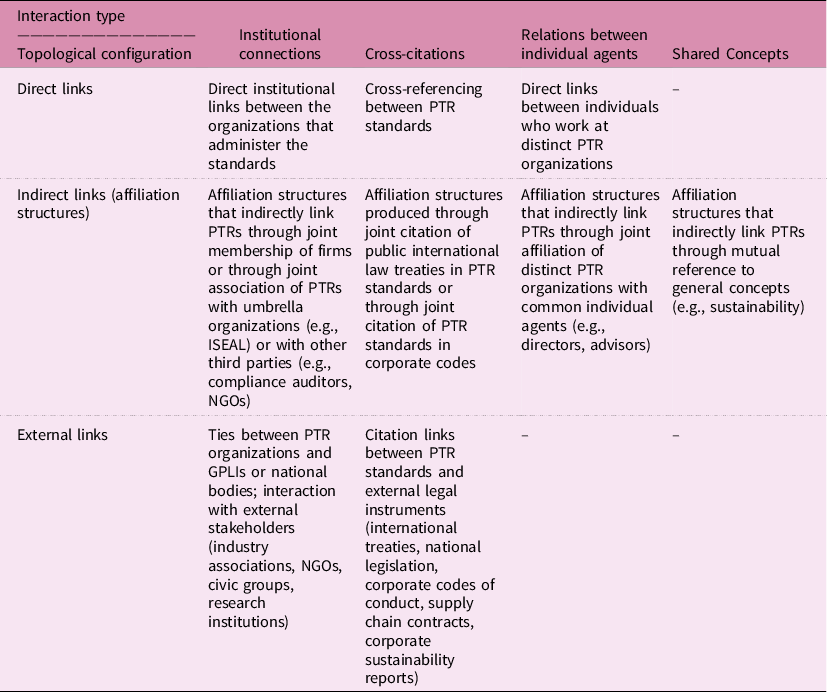

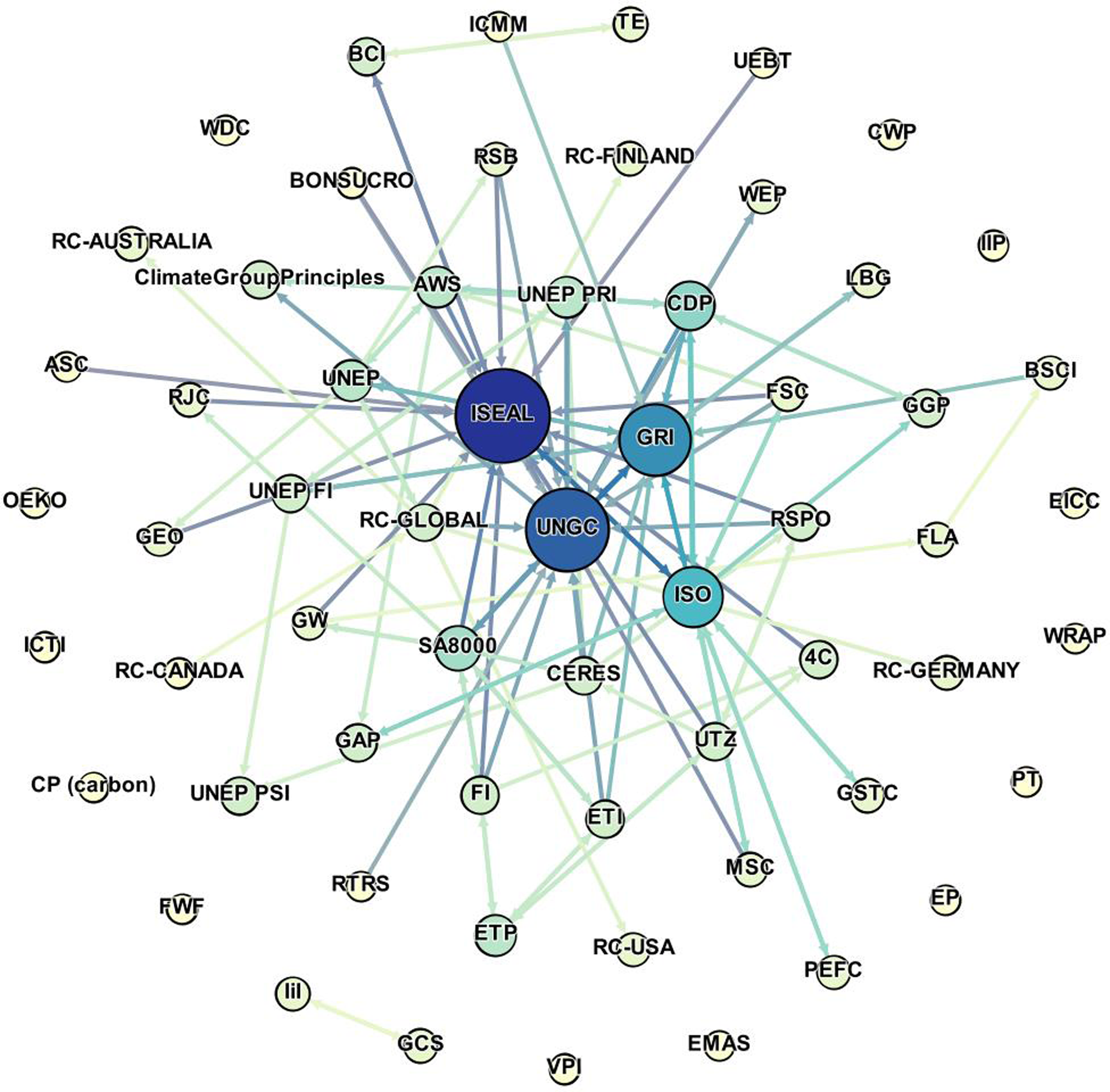

Is there evidence to support the idea of network authority? In a recent study of CSR standards (a joint work with Ofir Stegmann), we demonstrated that an extensive network of cross-citations of the type envisaged above has indeed evolved in the domain of CSR standards.Footnote 77 We found that our sample of 57 prominent CSR codesFootnote 78 formed a well-connected citation network: 53 of 57 codes (92.98 per cent) were part of one network, that is, they either cited at least one other code or were cited by another code. We found that the network included 1,538,060 cycles linking the nodes. A cycle is a sequence of nodes in which each node cites the next one in the cycle, and the ‘last’ node cites the ‘first’ (the denotation of first and last is, naturally, arbitrary). Each cycle differs in the number and identity of its nodes (thus, A → B → C is different from A → B → C → D). We omitted trivial cycles formed by self-citation (A → A) and deleted duplicate cycles. The four longest cycles in the network included 28 nodes, and the 27 shortest cycles included two nodes that cited each other. The graph of the citation network is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The citation graph of CSR codes (citation layer).

I also examined the extent to which the standards contain references to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).Footnote 79 I selected the CBD because it is one of the central global environmental treaties. I found that out of the 57 codes, 11 included references to the CBD, with different levels of intensity (see Table 2).

The existence of a dense structure of cross-references in the CSR domain constitutes a first step in my argument. It does not provide evidence for the emergence of legal validity or legal authority, which is much more difficult to capture empirically.

3.2.3 The constitutional aspects of network legality

An important feature of the model of transnational networked authority is that it allows us to distinguish between constitutionalized structures of legal authority and power-based regulatory structures.Footnote 80 Some authors, such as Veerle Heyvaert and Martin Loughlin, have argued that transnational (or global) law should be understood principally as a form of regulatory action: ‘expression of a type of instrumental reason that informs the guidance, control, and evaluation mechanisms of the many regulatory regimes that now permeate contemporary life’.Footnote 81

The main challenge faced by the idea of network constitutionalism is to explain how a reflexive communicative dynamic can emerge despite the lack of an institutional infrastructure of the type that exists in the national domain (in particular, the triad of supreme court, parliament, and executive branch). I argue that the densification of multi-layered links in a system of PTRs can facilitate the emergence of cross-network, reflexive communicative processes of legitimation and accountability that are characteristic of constitutional regimes. I argue further that the network dynamic can also give rise to the emergence of institutional mechanisms of co-ordination and accountability that can enhance the reflexivity of the network. The outcome of these processes is a new type of emergent constitutional structure – networked constitutionalism – which transcends the instrumental rationalities of each regime considered alone. Unlike the hierarchical structure of state-based constitutionalism, networked constitutional structures are horizontal. They are based on horizontal forms of accountability that stress mutual monitoring and review, peer accountability, and transparency. Previous studies that explored the idea of network-driven accountabilityFootnote 82 have stopped short of embedding it in explicit network analysis.Footnote 83

Networked constitutionalism depends therefore both on the development of opportunities for reflexive communication through network-driven forms of interconnectedness and on the evolution of second-order mechanisms of co-ordination, accountability and review. Such network-based reflexive political structure can emerge through the evolution of dense inter-connectivity across the layers that link the PTR institutions. The direct institutional links between PTR organizations create a space for direct dialogue and monitoring. Affiliation structures that link PTR organizations with third parties, such as certified corporations, umbrella organizations (e.g., ISEAL Alliance), compliance assurance or auditing bodies, public international law bodies such as UNEP or ILO, and civic organizations such as World Wildlife Fund, Amnesty International, and Oxfam International provide extensive opportunities for political deliberation. By creating a space for deliberation, observation, and cross monitoring the PTR network can facilitate the emergence of a reflexive network dynamics.

But network constitutionalism also depends on the evolution of central mechanisms of co-ordination, accountability and review. Accountability refers to the normative and practical capacity of some actors to hold other actors accountable to a set of normative requirements, to judge whether they have met their responsibilities under these requirements, and to impose sanctions in case of failure.Footnote 84 In the CSR domain for example, prominent examples of accountability mechanisms include the meta-regulatory standards of ISEAL and AccountAbility’s AA1000AP (2018) standard. ISEAL’s Code of Good Practice requires standard setters to engage with a balanced and representative group of stakeholders in the development of standards,Footnote 85 and ISEAL’s Assurance Code requires scheme owners to establish a procedure for complaint resolution, with the powers to investigate and take appropriate action about relevant complaints.Footnote 86 The AccountAbility AA1000AP (2018) standard supports both organizational users and assurance providers by furnishing a roadmap for achieving accountability, which it defines as ‘the state of acknowledging, assuming responsibility for and being transparent about the impacts of an organisation’s policies, decisions, actions, products, services and associated performance’.Footnote 87 The evolution of network-wide accountability mechanisms is critical for the legitimacy of the network and its constituents.Footnote 88

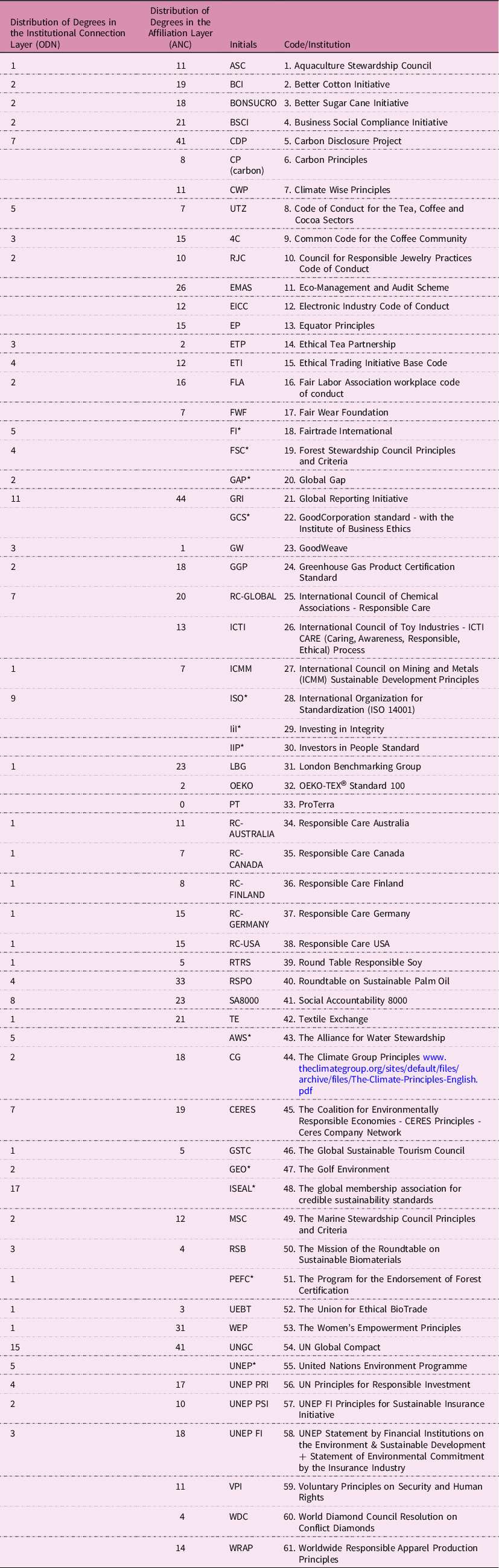

My previous work on the network of CSR regimes provides tentative support for the idea of network constitutionalism. In an article, co-authored with Reuven Cohen and Nir Schreiber, we studied a sample of 49 prominent CSR regimes. We analysed the direct institutional links between the CSR schemes (the organizationally derived network, the ODN layer).Footnote 89 We distinguished between five types of institutional connections: governance, partnership, compliance co-operation, membership, and support. Institutional links are directed, except for partnership, which is symmetrical. This analysis generated a directed and unconnected graph with 61 nodes and 116 edges. We considered all edges as bi-directional because the direction of the edges (as derived from the institutional analysis) was not critical for the analysis of network dynamics (e.g., diffusion of ideas and norms). We focused on the largest weakly connected component (WCC), which consisted of 46 organizations. The analysis of the ODN revealed a significant level of inter-institutional ties.Footnote 90 Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the ODN.

Figure 3. The organizationally derived network (ODN).

Large and dark circles correspond to nodes with large incoming degrees. The brightness of the edges is proportional with the incoming and outgoing degree of the node.

The analysis also provides evidence for the emergence of central co-ordinating nodes that can influence the flow of information within the system.Footnote 91 The authority of these co-ordinating PTR regimes is an emergent property that arises from their network position and is therefore distinct from the conventional hierarchical governance found in public law settings. The model of transnational networked authority suggests that PTR networks can develop informal steering mechanisms based on the spontaneous emergence of nodes with higher degrees. These centralized nodes can influence the flow of information within the network even without formal powers.Footnote 92 The analysis of the ODN layer revealed the central position of several organizations: GRI, ISEAL, RC-GLOBAL (Responsible Care), UNEP, and UNGC.Footnote 93 We complemented the analysis of the ODN layer by considering the affiliation network of organizations and firms (which consisted of 49 regimes and 31,987 firms).Footnote 94 This analysis corroborated the former results, revealing the central position of several additional regimes: CDP, RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil), SA8000 (Social Accountability 8000) and WEP (Women’s Empowerment Principles).Footnote 95 These findings suggest that despite the lack of formal hierarchy, some institutions may evolve into co-ordinating hubs that play a leading role in the network’s dynamics.Footnote 96

The first co-ordination function that these schemes provide is normative. Some pivotal institutions, such as GRI and UNGC, produce general overarching norms. Other central organizations, such as WEP, SA8000, and CDP, produce more particularistic norms (gender equality, labour rights, carbon accounting), which have gained cross-sectorial influence. The second type of co-ordinating function is institutional: organizations such as ISEAL play a key role in bringing the PTRs together. It is beyond the scope of this article to examine in detail the function that each of these institutions plays. I focus on two key examples. The UN Global Compact Ten Principles have become the cornerstone of the CSR policy of many corporations. This is reflected both by the large number of organizations that are associated with the UNGC (19,290 as of 26 December 2021)Footnote 97 and by the incorporation of the UNGC Principles into the supplier codes of conduct of private corporations.Footnote 98 ISEAL Alliance develops meta-regulatory standards, focusing on such questions as public engagement and transparency.Footnote 99 It also develops geospatial data and mapping tools, such as the Certification Atlas, which allows members and the public at large to evaluate the spread of CSR certifications and to overlay information on certified entities with other geospatial data.Footnote 100

3.2.4 Network steering: The power of synergy

Steering refers to the capacity of transnational legal systems to influence the behaviour of third parties without the support of state administrative infrastructure (external steering).Footnote 101 Legal systems cannot persist if they have no steering capacity.Footnote 102 External steering can be attributed, first, to the binding power of private transnational norms. The self-validation capacity of PTR networks invests the rules promulgated by network members with normative power, irrespective of the coercive capacity of the system.Footnote 103 The second mechanism reflects the synergistic effect of the network. The links between the various regimes and their enforcement mechanisms generate positive externalities and a synergistic effect that enhances the regulatory efficacy of the PTRs. This synergistic effect materializes only when the network exceeds certain structural and dynamic thresholds across its various layers.

I argued above that the institutional links between PTR bodies (e.g., CSR organizations) create a synergistic effect that enhances the regulatory efficacy of the network (both from an aggregated perspective and from the individual perspective of the member regimes), by creating positive externalities between the enforcement mechanisms of the various regimes.Footnote 104 In the context of the CSR regimes, I argue that the normative and compliance complementarities between the CSR schemes make it more difficult for firms that take on the commitments of several schemes to renege on their CSR commitments.Footnote 105 A good example of this synergistic effect is the issue of disclosure. Many CSR schemes include disclosure requirements. For example, Global Compact, Responsible Care, and Equator Principles have developed unique reporting frameworks that are embedded in their institutional structure.Footnote 106 As a firm takes on the disclosure requirements of several CSR schemes, which may cover different aspects of its operations, it becomes much more difficult for it to cheat vis-à-vis each of the CSR schemes because its organizational structure becomes more transparent. These synergistic effects represent both synergies of scale (because they depend on the existence of a sufficiently large network involving both codes and firms) and functional complementarities (reflecting how different CSR schemes mutually supply each other’s lack).

In a recent paper with Reuven Cohen and Nir Schreiber, we tested the synergy hypothesis empirically.Footnote 107 We hypothesized that firms with multiple CSR certifications display a stronger CSR performance than do their peers with fewer certifications. Our hypothesis was based on a network signalling model (NS model), according to which firms use multiple certifications to signal their type: green firms use certification or membership in CSR schemes to distinguish themselves from green-washers.Footnote 108 What makes certification or membership in CSR schemes a credible signal is the differential cost structure of multiple certifications. The cost of multiple certifications is higher for an untruthful firm than for an honest one. The credibility of the signal is preserved because it is costly to produce. According to the NS model, the number of certifications correlates positively with CSR performance.

To test this hypothesis, we compared our data on multiple certifications with data on global CSR rankings, obtained from Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) and FTSE4Good, which are widely considered to be credible proxies for good CSR performance.Footnote 109 We found, first, that firms selected as constituents of either the DJSI or the FTSE4Good sustainability indices were more likely to be part of the CSR-scheme network, that is, to be certified by at least one code, than were firms that were not selected from the universe of candidate firms. Furthermore, we found that a firm that was certified by multiple schemes was more likely to be included in the indices than one with fewer certifications, that is, as the number of certifications grows, so does the probability of a firm being included. By showing that firms with a larger number of certifications demonstrate stronger sustainability performance, these findings provide tentative support for the synergistic argument. Further research, using longitudinal data, is needed for a complete corroboration of this claim.

4. The legal-doctrinal effect of private transnational norms

The idea of transnational network authority can change the way courts and other legal decision makers treat private transnational norms. Below I illustrate this thesis using examples from the CSR domain.

4.1 Network authority and the public recognition of PTR norms

As national and international regulatory schemes are becoming increasingly dependent on PTRs, the question of how to select and monitor these private schemes is becoming particularly critical. Two examples can illustrate this problem. The Paris Agreement has formally recognized the potential contribution of non-governmental bodies to the fight against climate change by establishing the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action.Footnote 110 The most recent manifestation of this trend is the Race To Zero (RTZ) campaign, which formed a coalition of leading net zero initiatives in the largest ever alliance committed to achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050.Footnote 111 The RTZ campaign has established a unique set of minimum criteria required for participation in it, and an institutional body (the Expert Peer Review Group) that is responsible for managing the campaign.Footnote 112 RTZ criteria provide a general framework for reduction of emissions, but they leave out many critical issues, such as the way in which credits should be used in neutralization claims.Footnote 113 These questions are left unanswered by the Paris framework. Private standards, such as the Gold Standard, the Verra VCS Standard, Plan Vivo, and the American Carbon Registry Standard provide varied responses to this lacuna.Footnote 114 It remains unclear, however, how to choose between the various standards.

Another example is the European Union Directive 2014/95/EU on the disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (the NFI Directive).Footnote 115 The NFI Directive requires large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees to publish reports on the policies they implement in relation to environment protection, treatment of employees, respect for human rights, anti-corruption, and diversity on company boards. It gives companies significant flexibility regarding the way in which they carry out their obligations under the Directive. The Commission has published two guidelines on the methodology for reporting non-financial information (according to Article 2 of the Directive). One of the key issues explored in the guidelines is their consistency with recognized reporting standards.

I argue that network thinking can offer valuable insights regarding the design of hybrid public-private schemes. Standards that are part of a constitutionalized network and occupy a more central position in it should be given more credence than comparable standards that are not part of such a network or are highly peripheral.Footnote 116 Indeed, some of the disclosure standards that were listed above as key actors in the CSR network, such as UNGC, GRI, and CDP, were also included in the Commission Guidelines.Footnote 117

4.2 Transnational regulatory liability

The idea that network-embedded PTR organizations can produce binding norms should change the way we think about the liability of PTR organizations. If the norms produced through PTR networks are not merely ‘cheap talk’, the potential liability of PTR organizations to harm caused by a faulty exercise of their authority comes as a natural corollary. The idea that PTR organizations may be subject to tort liability departs from current transnational law theorization, which has tended to focus primarily on the liability of multinational enterprises.Footnote 118 It is inspired by two legal doctrines, statutory torts, and constitutional torts,Footnote 119 but goes beyond these, by grounding the liability of PTR bodies in jurisprudential structures that they themselves have created. Although this idea has not been explored in the current transnational law litigation, it is possible to find some tentative support for it in recent case law.

To illustrate this point, I focus on a particular case study, the Ali Enterprises disaster. As this case illustrates, the liability of PTR organizations may arise through two different paths: (i) a faulty design of the applicable standard, leading to an adverse outcome (e.g., health and safety standard); and (ii) a faulty implementation of a (non-faulty) standard, similarly leading to an adverse outcome. In both cases, liability can be grounded either in the norms created by the network or in general principles of tort law.Footnote 120 The discussion below does not resolve all the questions that the idea of PTR liability raises, and I defer an exhaustive discussion of the doctrinal aspects of this thesis to future work.

On 11 September 2012, Ali Enterprises, a sewing factory based in Pakistan, exploded into flames, claiming the lives of 258 people, and seriously injuring 32.Footnote 121 Ali Enterprises, which was one of the main suppliers of the German textile producer and retailer KiK, received its SA8000 safety certification in August 2012, a month before the deadly accident.Footnote 122 RINA Services SpA (RINA), an Italian company, issued the certificate for the factory.Footnote 123 RINA operates as a compliance agent, which provides inspection, assessment, and certification services.Footnote 124 The Ali Express certification followed an inspection by RI&CA, a RINA subcontractor in Karachi. Investigations conducted after the fire showed that hundreds of lives could have been saved if lax safety standards in the factory had been identified and acted upon on time.Footnote 125 Claims against the factory focused on the presence of heavy iron bars on the windows,Footnote 126 the lack of emergency exits,Footnote 127 the fact that the few available exits were locked, and generally highlight the lack of adequate fire safety measures.Footnote 128

Here I focus on the potential liability of Social Accountability International (SAI) (the developer of the SA 8000 standard) and RINA (its compliance agent) for the damage, leaving aside the question of the potential liability of KiK.Footnote 129 I argue that the liability of SAI and RINA stems from their being part of a constitutionalized PTR network. It is only because we take seriously the regulatory power of SAI and RINA, that it makes sense to examine their responsibility for the Ali Enterprises tragedy. The Ali Enterprises case has led to multiple lawsuits and extensive deliberation in various fora, in which the responsibility of both SAI and RINA for the accident was discussed. For example, following the accident, SAI took various steps to improve the fire safety components of the SA8000 standard, noting in a summary document that the Ali Enterprises ‘tragedy was a watershed moment that resulted in a series of productive improvements in SA8000’s health and safety performance element specifications to improve emergency preparedness and fire safety’.Footnote 130

The responsibility of RINA for the accident was discussed by the Italian OECD National Contact Point (NCP), following a complaint filed by an international coalition of eight human rights, labour, and consumer organizations, under the framework of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Although NCPs, unlike national courts, lack the authority to determine the liability of a party to an accident, and their primary function is to promote a shared resolution of issues related to the implementation of the OECD Guidelines, the decisions of the Italian NCP in this case indicate that it considered that RINA should bear responsibility for the accident. In its Initial Assessment of the case, the Italian NCO noted that ‘the high number of victims of the fire is an indicator that the factory was lacking the basic conditions of a safe working environment, as required by the OECD Guidelines, international law and the SA8000 Standard’. It noted further that ‘[c]onsidering all the above, the complaint seems material and substantiated, and it can be found a link between the enterprise’s [RINA’s] activities and the issue raised’.Footnote 131 Based on this analysis, the NCP has made three recommendations in its Final Statement regarding RINA’s responsibility:Footnote 132

-

1. ‘[T]he Company make a humanitarian gesture without any implication in terms of liability’;

-

2. ‘[T]he Company take action to show its sympathy for the tragic event’;

-

3. ‘[T]he Company when operating in countries and sectors at risk, such as in the case of the textile sector in Pakistan, carry out a risk-based due diligence effective and adequate to the risks registered, as recommended by the OECD Guidelines’.

5. Policy implications and future challenges

In this article I developed a relational model of transnational legal authority, which is based on a network analysis of the interactions between private transnational regulatory regimes. By offering a further layer of governance functionality that complements the international treaty system, PTR networks can contribute to the resilience of the global governance system by increasing its diversity and by providing redundancy. Diversity provides governance systems with multiple, alternative courses of action; when a system experiences disruption along one pathway, an alternative pathway can be used to achieve the same goal. Redundancy provides the system with ‘insurance’ by allowing some system elements to compensate for the loss or failure of others. Diversity and redundancy become important for the functionality of the system in times of crisis.Footnote 133

At the same time, using the steering potential of PTR networks raises a complex design challenge, reflecting the intrinsic difficulty of controlling self-organized systems. Guided self-organization requires policymakers to tread a fine line between over-engineering, which could undermine the self-organizing capacity of the system, and an overly lax supervisory approach, which could increase the non-determinism of the system and undermine policy reliance ex ante.Footnote 134 Achieving the right balance between design and self-organization constitutes a significant theoretical and policy challenge.

The analysis in this article amounts only to a first step in the full elaboration of the concept of transnational networked authority. I can list three key challenges that should be addressed in future research, involving both the sociological and doctrinal aspects of my argument. The first challenge concerns the dynamics of PTRs networks. It involves three interrelated questions:

-

(1) the expansion of the network through the addition of new nodes (e.g., PTRs, firms, and other non-state organizations). The expansion of PTRs networks may be driven by different mechanisms such as (a) preferential attachment: the preference of firms to link with more highly connected PTRs;Footnote 135 (b) regulatory reputation: the preference of firms to link with PTRs with stricter compliance framework, irrespective of their degree centrality; and (c) structural homophily: the preference of firms to connect with PTRs with similar policy objectives.Footnote 136 Exploring these alternative explanations requires further empirical work based on longitudinal data.Footnote 137

-

(2) The formation of new links between existing network nodes (e.g., through the certification of firms by existing PTRs). This question raises further puzzles, for example, how the formation of links in one layer (e.g., direct organizational ties) influences the formation of links in another (e.g., citation layer).

-

(3) The dynamics of information flow. Switching to a multi-layer perspective exposes the multiple paths through which information can flow between different nodes, potentially shifting between different layers. Studying the spread of information in legal contexts presents a theoretical and empirical challenge, which has not been adequately addressed in the current legal and network literature.Footnote 138

A second theoretical and empirical challenge concerns the idea that PTRs may possess varying degrees of authority, which depend both on the overall structure of the network and on its positional properties.Footnote 139 One way to understand this claim is to distinguish between regimes that are located at the core of the network and those that are located at its periphery. In a core-periphery structure, some nodes are part of a densely connected core and others are part of a sparsely connected periphery. Core nodes tend to be reasonably well-connected both to other core nodes and to peripheral nodes; peripheral nodes are not well-connected to either core nodes or to each other.Footnote 140 A core structure in a network is thus not merely densely connected but also tends to be ‘central’ to the network (e.g., with respect to the mean closeness of core nodes to other nodes in the network).Footnote 141 From a jurisprudential perspective, core regimes are assumed to possess stronger legal force than peripheral ones, and consequently their normative output should receive more weight by state regulators and state courts. A similar distinction can be developed between networks that have different levels of cross-layer density. More work needs to be done in clarifying the relation between network properties (core-periphery, density), the legal force of the relevant regime, and the policy and doctrinal implications of this degree-based framework.

Finally, more work should be done on refining the doctrinal implications of the idea of network authority, especially with respect to the potential liability of PTRs and other actors that take part in transnational value chains.

Appendix A. The List of CSR Schemes

Appendix B. CSR Schemes ODN-Citation layer