1 Introduction

In August 1965, the trial with the case number 4 Ks 2/63, the largest ever in post-war Germany, finally came to an end after 183 days of hearings and a total duration of twenty months. The scale of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial (1963–5) was not only unique on account of its length, but also because of the number of individuals involved. Along with the leading judge, Hans Hofmeyer, three additional judges, six jurors, four state attorneys, three joint plaintiffs and nineteen defence lawyers took part in the proceedings. Moreover, two substitute judges, five back-up jurors and numerous advisors were added and a total of 360 witnesses questioned for the case. The court case itself tried part of the SS personnel from the Auschwitz–Birkenau concentration and extermination camp, altogether twenty-two accused individuals. The sentencing commenced on 19 August 1965. It lasted two days, with a verdict that resulted in six life sentences, ten prison sentences ranging from three-and-a-half to fourteen years, and one juvenile sentence of ten years. Two of the defendants were excluded from the proceedings due to illness, and three were acquitted. Among those being tried were two dentists:Footnote 1 Willy Frank, 1st SS camp dentist, and Willi Schatz, 2nd SS camp dentist, both stationed at Auschwitz. While Frank was sentenced to seven years of imprisonment, Schatz was acquitted due to lack of evidence. As opposed to most of the other defendants, Schatz was never held in custody. Why did a dentist like Schatz – eighteen years after the fall of the Third Reich – find himself in the dock, especially considering that the overall responsibility of an SS dentist was merely treating SS personnel, prisoners and German civilians at the camp?Footnote 2 What insights might we gain into the topic of dental medicine and National Socialist crimes based on his particular biography?

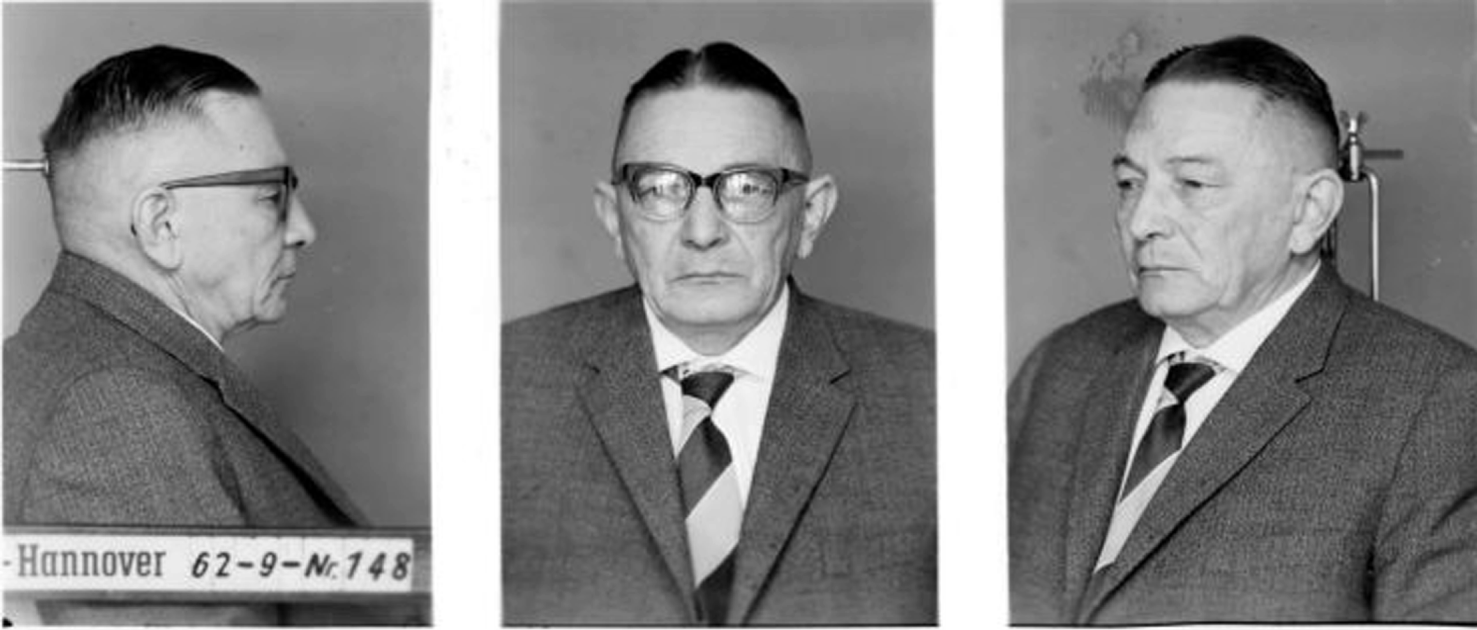

At first glance, his involvement as one of the accused in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial undoubtedly places Schatz among the infamous and often discussed dentists of the Third Reich.Footnote 3 In the mid-1960s, various overviews and encyclopaedias outlining particular individuals provided us with short biographies about his person.Footnote 4 These are mostly based on reports provided by the prosecutors involved in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial and perpetuated several biographical errors while depicting Schatz as only one of numerous accused individuals (Figure 1). Precisely because of these issues, a critical assessment of his role as 2nd SS camp dentist and of his own accounts has not yet taken place.

Figure 1: Police photograph of Willi Schatz 18 September 1962 (Public prosecutor’s office Frankfurt am Main).

For various reasons, Schatz’s biography offers us an exemplary point of access to the complex of dental medicine and National Socialist crimes. First of all, his career in the party was characterised by an interesting rupture: in the 1930s, Schatz was banned from all party organisations due to the assistance he had provided for an abortion. Despite this stain on his record, he was later able to serve as an SS dentist at Auschwitz and at Neuengamme. Second, we can reconstruct the tasks and duties assigned to SS dentists at Auschwitz based on his story. Along with his complicity in various National Socialist crimes, his biography also reveals the responsibilities officially assigned to the position of SS dentists as well as their treatment of prisoners. Tellingly, former imprisoned dentists and dental technicians described Schatz as having a ‘kind personality’.Footnote 5 Third, as previously mentioned, though the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial acquitted Schatz of his involvement in the selections, more recent studies of photographs taken at Auschwitz identified Schatz as part of the selection personnel.Footnote 6

2 Dentists and Concentration Camps: The State of Research

While research into National Socialist crimes at concentration camps provided us with valuable information about daily life at these camps and – to some extent – about the work of the leading concentration camp doctors,Footnote 7 researchers have paid relatively little attention to the dental facilities at these camps and the duties of the SS dentists stationed there. Although dental gold robbery is a well-known and documented crime perpetrated in concentration camps, there are few systematic studies about dental practitioners and their actual responsibilities at the various concentration and extermination camps. In this context, the dental gold issue has taken on an ambivalent role. On the one hand, it represents the manifestation of a barbaric attitude of exploitation and dehumanisation; on the other hand, it has perpetuated a narrow approach to this topic of study. One of the problems is that scholarly documentation about service directions for concentration camp dentists have generally been based on statements from supervising personnel at the respective camps. Rudolf Höß, camp commander at Auschwitz until 1943, made the following statement in his records from his imprisonment in Krakow about the ‘non-medical duties’ of a concentration camp dentist:

The dentists had used ongoing spot checks to assure that the imprisoned dentists at the special command were extracting the gold teeth of all the gassed individuals and throwing them into the supplied containers. Additionally, they had to supervise the melting of the dental gold and ensure its proper storage and delivery.Footnote 8

Similar statements can also be found for the dentists at other camps. Physician Dr Percy Treite described the duties of the dentist Martin Hellinger, at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, as follows: ‘It was Hellinger’s task to rip out the gold teeth of the victims once I confirmed that they were dead.’Footnote 9 Collecting gold crowns was also described as one of the primary tasks of the dental station at Dachau: ‘This dental gold was extracted from deceased or killed prisoners before they were burned in the crematorium. The SS dentist and a medical orderly (Sanitätsdienstgrad) were also present for this procedure.’Footnote 10 These testimonies not only highlight the scholarly focus on the issue of dental gold, they also indicate that other medical duties performed by dentists at the concentration camps had been sidelined. In most cases, this specific topic receives marginal treatment – mostly in a wider framework of descriptions of camp health services or concentration camp medical professionals and their duties.Footnote 11 The existing in-depth investigations of the activities carried out at dental stations and the duties of concentration camp dentists have – so far – received little consideration from the scientific community.Footnote 12 This lack of attention likely has to do, in part, with the publication formats: in many cases, such studies are either unpublished doctoral theses,Footnote 13 papers released by little-known publishers, publications in a language other than English or German,Footnote 14 or titles that do not indicate that they deal with SS dental stations.Footnote 15 Our knowledge about the involvement of dental representatives in the selection and extermination process, therefore, is minimal and fragmentary.Footnote 16 Even more recent publications about dental practice under National Socialism provide few essential new findings, but rather expand on the work of existing investigations.Footnote 17

The tendency to neglect the topic of camp dentists can also be attributed to a lack of sources – a challenge that prosecution authorities still face today when trying to identify potential Nazi criminals. Unclarity is particularly predominant regarding research about concentration camp dentists in both quantitative and qualitative terms; for example, even in determining the number of dentists present in the camps. Lasik has counted eleven dental care workers at Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945,Footnote 18 and according to Tannenbaum there were two and, in some years, even three SS dentists at the concentration camp in Flossenbürg.Footnote 19 According to current and still unpublished studies conducted at the Aachen Institute for the History, Theory and Ethics of Medicine, we may assume that an even higher number of dentists existed: these studies have so far identified seventeen at Auschwitz and eleven at Flossenbürg. In Mauthausen, there were even nineteen dentists and sixteen in Dachau.Footnote 20 These disparate figures point to the enormous degree of fluctuation within the various concentration camps; they also shed light on the fact that dentists also comprised an integral part of the medical camp administration.Footnote 21 As such, the profession of a concentration camp dentist deserves more in-depth, analytical consideration, especially in those areas where it intersected with daily life at the camps, concerning the provision of dental care and the dentists’ active participation in National Socialist crimes.

To arrive at conclusive statements, the approach we adopt here focuses on the camp complex at Auschwitz and on the dental duties and responsibilities of concentration camp dentist Willi Schatz as a case study. The following sections clearly show that Auschwitz held a special status and that the tasks assigned to its SS dentists cannot merely be presumed to also apply to dentists at other concentration or extermination camps.

3 Methodological Approach, Analysis of Source Material and Research Questions

As opposed to previous perpetrator research, this study will avoid relying exclusively on basic biographical information to address the issue of complicity in National Socialist crimes. As such, the following considerations are key to our investigation – especially with regard to the motivations behind participation in National Socialist crimes.

First, it is more fruitful to focus on the on-site situation and actions at Auschwitz, instead of ideological positions expressed in documents, by memberships, or later testimonies. Overall, the situation at the camp constituted the framework in which National Socialist perpetrators acted or could have acted.Footnote 22 Moreover, the perpetrators were also subject to a particular local and time-specific dynamic.

These aspects allow, second, the assumption that Schatz’s participation in National Socialist crimes did not merely result from specific National Socialist attitudes he may have held. His involvement cannot be explained through his political party career nor his worldview alone. Instead, his positions must be interpreted from a praxeological perspective. National Socialist ideology brought forth certain communal practices that generated structures and, at the same time, communicated specific role expectations. Particularly in the context of concentration and extermination camps, individuals had to conform with certain roles in order to be able to operate within the overall system. The conclusions reached by Karin Orth with regard to role of the SS in concentration camps – according to which the antisemitic and racist consensus was constantly being reaffirmed through common acts – should, therefore, be accepted as accurate.Footnote 23 Moreover, this determination can, and must, be extended to SS physicians and dentists as well as to those responsible for the selections in general.

Our approach here rests on the hypothesis that even in a place like Auschwitz, it was only in certain states of emergency that nearly the entire personnel was integrated into the extermination machinery. One such state of emergency – or, rather, a specific situational dynamic – worth mentioning was the so-called Ungarn Aktion (special action Hungary, starting in May 1944), throughout which the majority of the approximately 450 000 deported individuals were promptly murdered. As we will show, this campaign had significant implications for the SS dental personnel at Auschwitz, who had previously found themselves far more distanced from the terror and orchestrated murder campaigns than the SS physicians.Footnote 24 We will pay special attention to identifying the formal as well as the de facto command structures and the administrative and organisational regulations and tasks. What position did SS dentists in general and Willi Schatz specifically assume at Auschwitz? Who did they report to and what were their specified duties at the camp? How did their original responsibilities change, and what were the mechanisms behind this added flexibility in their role and task assignments?

As in many areas of National Socialist health policies, camp dentistry was also characterised by a high degree of disagreement over competencies and possibilities for exerting influence among various SS offices. At the same time, these matters also touch upon the core characteristics of National Socialist domination. It has to be clarified as to what possibilities and opportunities this ‘confusion of offices’ specific to National Socialism opened up for dentists in everyday camp life.

As there are no personal records from Willi Schatz, our main body of sources consists of archival documents, the legal records, hearings from the First Frankfurt Auschwitz trial (1963–5), photographs taken at Auschwitz and reports from survivors. Considering the specific contexts in which these were generated, making use of such diverse sources demands critical assessment. In reference to records from criminal proceedings, Jürgen Keller and Sven Finger rightly suggest that there is a fundamental difference between statements made during investigative procedures and those made before a judge. We especially have to consider that the accused persons and suspects on trial are faced with a situation that ‘alters the willingness to make statements and recollections, particularly among the perpetrators and their former colleagues’.Footnote 25 With this potential pitfall in mind, all such statements must be reinforced by corresponding records, whenever possible.

4 Willi Schatz’s Path to Becoming an SS Dentist – A Biographical Sketch

Willi Ludwig Schatz was born on 1 February 1905 in Hanover, Germany, as the son of a dentist. It was here that he eventually received a high school diploma allowing him to enter university, though only after repeating two grades. He went on to study dentistry in Göttingen for ten semesters and passed the state exam in early 1932, attaining the title of Dr med by the end of the same year.Footnote 26

During the preliminary investigation by the public prosecutor’s office, Schatz indicated that he first joined the NSDAP in 1933, which the office and the court took to be correct at the Auschwitz trial. Several biographies about Schatz also continued to report this error until quite recently.Footnote 27 In reality, Schatz joined the NSDAP on 1 October 1932 (membership number 1357649). One year later, on 1 October 1933, he also joined the Sturmabteilung (SA), serving as a Sturmbann dentist as part of the II First Aid Station of the SA-Standard 73 (Hanover-Vahrenfeld Division) and achieving the rank of Obertruppführer.Footnote 28 In court, Schatz cited pressure from fellow dentist party members as the reason why he ultimately joined. He spoke of economic motives, in particular: ‘He would not have had been permitted to receive an insurance licence if he had not joined the party.’Footnote 29 Conversely, during the preliminary investigation in 1961, he emphasised: ‘In 1933, I visited an event held by our professional association. The NSDAP had practically staged it. At the end of the event, I joined the NSDAP.’Footnote 30 Regardless of whether his record confirms an earlier entry date into the party or not, this situation exemplifies the highly symbolic value associated with self-conformity to the Reich Association of Dentists in March 1933, which likely left a strong influence on his recollections as well.Footnote 31 The following is an excerpt from the publication Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen (ZM) on the occasion of the general meeting of the Reich Association from 23 March 1933, at the end of which Ernst Stuck was appointed to the position of Reichszahnärzteführer [Reich dentist leader]:

Numerous colleagues from the Reich came wearing S.A. formation uniforms and steel helmets (…) The election of the board for the Reich Association of German Dentists resulted in complete agreement on the goals of the new Reich government. We welcome the Führer of the new Germany! [T]he Reich Association of German Dentists is the first academic association that has seamlessly found its way to the national government. [W]e must expect that every colleague will firmly stand behind the coherent whole and play his part for the best of our profession and thereby for the health of our fellow countrymen – for our German fatherland.Footnote 32

Upon closer investigation, Schatz’s claim that it would not have been possible to obtain an insurance licence without being a member of the party proves to be just as inaccurate as the date on which he proclaimed to have joined the party. The insurance licence primarily served as an instrument of exclusion for ‘non-Aryan’ or ‘communist’ dentists and not for rejecting dentists lacking a party membership. It was not until 1935 that a vaguely formulated passage was included in the licensing regulations for insurance providers, threatening to exclude any dentists from retaining their insurance licence who ‘do not assure that they will unreservedly stand up for the National Socialist state at all times’.Footnote 33 The claim that non-membership was disadvantageous in this context thus cannot be confirmed. Starting in 1933, Schatz practised dentistry at his private medical practice in Hanover and provided voluntary examinations in his SA troop.

Just a few years later, his position in the NSDAP and the SA would fundamentally change. In 1935, Schatz became engaged to Else Merten, resulting in a pregnancy in 1936. Because both Merten and her mother had tuberculosis, Schatz feared that he would be accused of fostering an ‘unworthy life’ and face the associated consequences from the party. Prior to the passing of the Regulation to Combat Transmittable Diseases in 1938, tuberculosis was classified as an illness of poverty and led many people to be admitted to asylums and care institutions that conducted forced sterilisations.Footnote 34 In response, Schatz coerced Merten to undergo an abortion. However, as paragraphs 219 and 220 were reintroduced into the criminal code in 1935, prohibiting mothers of ‘good blood’ to have an abortion, Schatz was convicted on 4 October 1937. He was found to have not only provided the address of a female abortionist to Else Merten but also to have paid for the abortion. The Hanover court of lay assessors imposed a fine of 400 RM in lieu of twenty days of imprisonment.Footnote 35 The Hanover Gestapo took this opportunity to ask the party administration how they should proceed with Willi Schatz. In 1938, the Hanover district court finally issued him a warning and disqualified Schatz from holding a party office for two years to come. One of the mitigating factors mentioned was ‘that the birth of a genetically ill child cannot reflect the intention of a state that aims to maintain healthy and strong offspring’.Footnote 36 A second hearing took place during a review proceeding at the South Hanover-Brunswick district court. Following the rejection of an appeal by Schatz, the proceedings ended on 30 November 1939 with his expulsion from the NSDAP and SA.Footnote 37

Even though Schatz, up to this point, had always received positive evaluations at his various political posts, his party dismissal was first to be discussed once the war had ended. The authorities justified the exclusion from the party by stating that ‘whoever, in the role of a doctor, refers a woman to an abortionist proves that he lacks the sense of responsibility that must be demanded of a doctor belonging to the NSDAP’.Footnote 38 Before being conscripted into the Wehrmacht on 15 June 1940, Schatz worked as a resident dentist in Hanover. Starting in June 1940, he joined the 3rd Company of Landesschützenbataillon 701, which was transferred to Dessau soon after that. It was here that he was trained as an infantryman. After the company returned to Hanover, Schatz was deployed as a vehicle operator and courier. Before his relocation to a medical station in Bückeburg at the end of 1942, Schatz was promoted to corporal. In his position as a medical corporal, he was sent to the army dental station in Hanover. There he worked as a dentist and was quickly promoted to the rank of a sergeant once again.

Schatz’s military deployment in the Altreich (within the borders of pre-1938 Nazi Germany) would decisively change starting in the summer of 1943. On 16 August 1943, he received an order from the Military District Command XI relieving him immediately from military service and transferring him to the Waffen-SS.Footnote 39 He left the Wehrmacht – with retroactive effect as of 3 July 1943 – with a transfer to the Waffen-SS under member number 151434 as of 22 July 1943.Footnote 40 Seeking to strengthen the manpower of the Waffen-SS, the principle of voluntariness had been abandoned by the regime starting in 1943, leading to forced transfers for some, as in the case of Schatz. This change in the recruiting policy was mainly driven by an overall shortage of physicians in the medical divisions of the Waffen-SS. Physicians were often replaced by dentists, who were much easier to recruit and who could subsequently be retrained as assistant physicians.Footnote 41 By August 1943, Schatz’s transfer took him to Oranienburg, upon his entry into the SS command headquarter – dental station – [Kommandantur Zahnstation] at Sachsenhausen. In line with career regulations for commanders [Führer] and sub-commanders [Unterführer], Schatz received his preparatory instruction for deployment as a concentration camp medical doctor at the SS Medical Academy in Graz in autumn 1943.Footnote 42 He would return once more to Oranienburg before being transferred to the SS command headquarter at Auschwitz on 30 January 1944. Additionally, Oranienburg housed Amtsgruppe D (concentration camps) of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA). Dienststelle DIII (medical services and camp hygiene) was under the direction of Enno Lolling,Footnote 43 the chief concentration camp physician who, in particular, dealt with medical and dental services for SS members. Willi Schatz likely met Hermann Pook here as well. Pook was the chief dentist of the SS-WVHA, who assisted Lolling as a dental advisor and who was responsible for the dental stations of all concentration camps.Footnote 44 As Sachsenhausen possessed a quite modern infirmary at this time, the dental station aptly served as a training centre.Footnote 45 It is evident that Schatz received training and preparation for his duties at Auschwitz while he was in Oranienburg. His transfer to Auschwitz on 30 January 1944 also went along with his promotion to SS Untersturmführer.Footnote 46

5 The SS Dental Station at the Concentration Camp Auschwitz

When Schatz arrived at Auschwitz in February 1944, he assumed the role of 2nd SS camp dentist. Willy Frank was 1st SS camp dentist, having been promoted to this position following the dismissal of the previous 1st SS camp dentist, Hauptsturmführer Karl Heinz Teuber, in July 1943.Footnote 47 Within the camp organisation, the SS dental station reported to the chief SS physician at Auschwitz, Eduard Wirths, who assumed office in September 1942. Wirths, for his part, reported to the chief physician of all concentration camps, Enno Lolling.

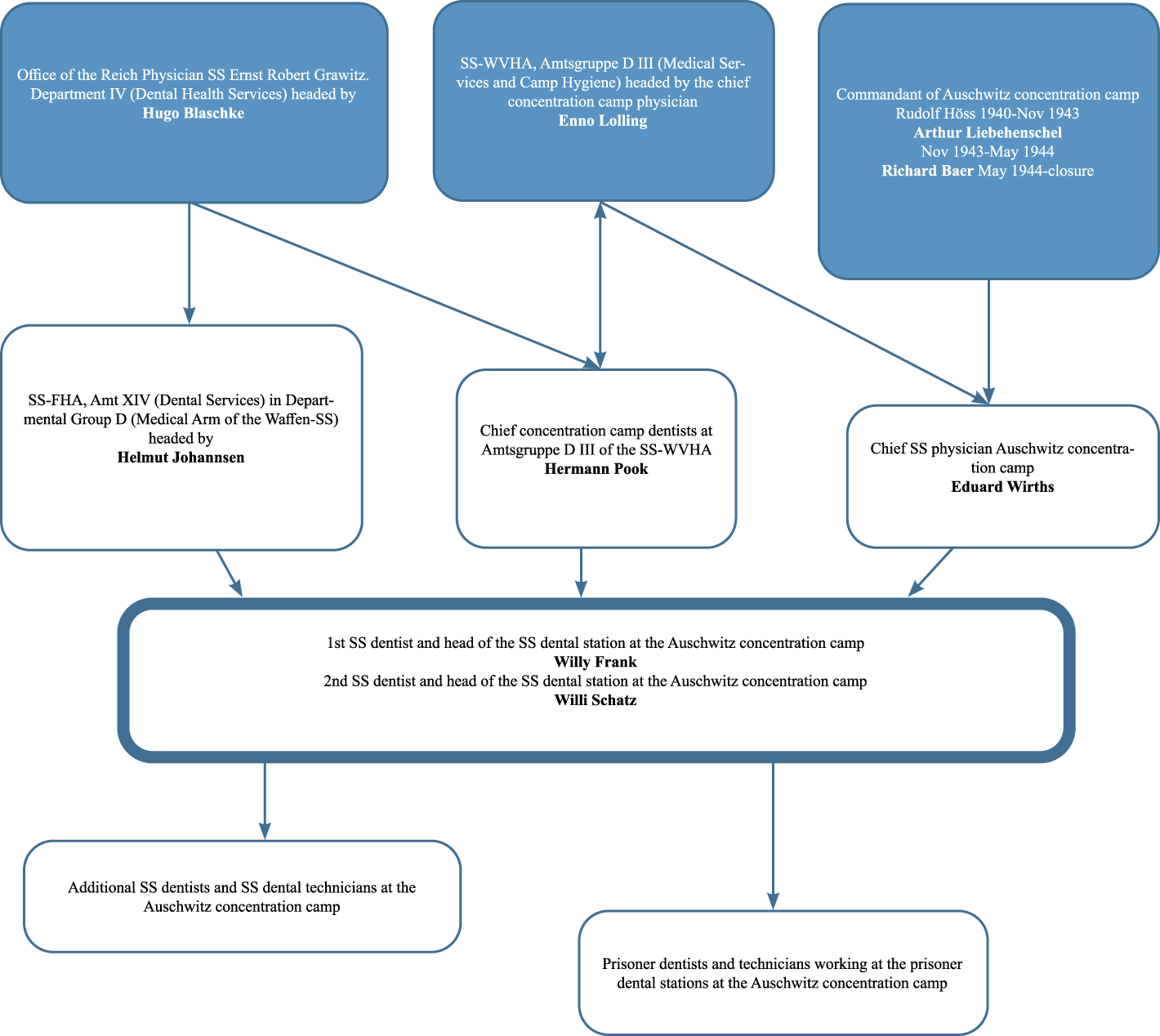

Figure 2: Overview of the polycratic command structure for the SS dental station at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the SS dentists did, however, face a complex situation: while subordinated to Wirths in terms of their professional conduct, they also received instructions and orders from the chief dentist of the SS-WVHA, Hermann Pook.Footnote 48 The polycratic command structure under National Socialism is reflected in the fact that the office of Reichsarzt SS [Reich Physician SS, Ernst-Robert Grawitz] also included a department for dental service, held by Hugo Blaschke. Blaschke had direct power to issue orders to Amt XIV (Dental Services) within Departmental Group D (Medical Arm of the Waffen-SS) under the SS Leadership Main Office [Führungshauptamt, SS-FHA]. Amt XIV was led by the SS camp dentist at Buchenwald, Helmut Johannsen and was responsible for supplying the SS dental stations with instruments and material.Footnote 49 In summary, the Auschwitz dental station was subject to three different command structures with disparate interests.

The SS dental station at Auschwitz was housed at the main camp [Stammlager]. In accordance with its staffing plan, the station was headed by two SS dentists and assisted by at least two SS dental technicians.Footnote 50 While other concentration camps did, at times, have more than one SS dentist in service, Auschwitz proves to have been exceptional due to its size. Whereas only one chief SS camp dentist provided service at other camps, Auschwitz had two.Footnote 51 The SS dentists had command over the SS dental technicians as well as the imprisoned dentists and technicians. As mentioned, a total of seventeen dentists have thus far been identified at this dental station.

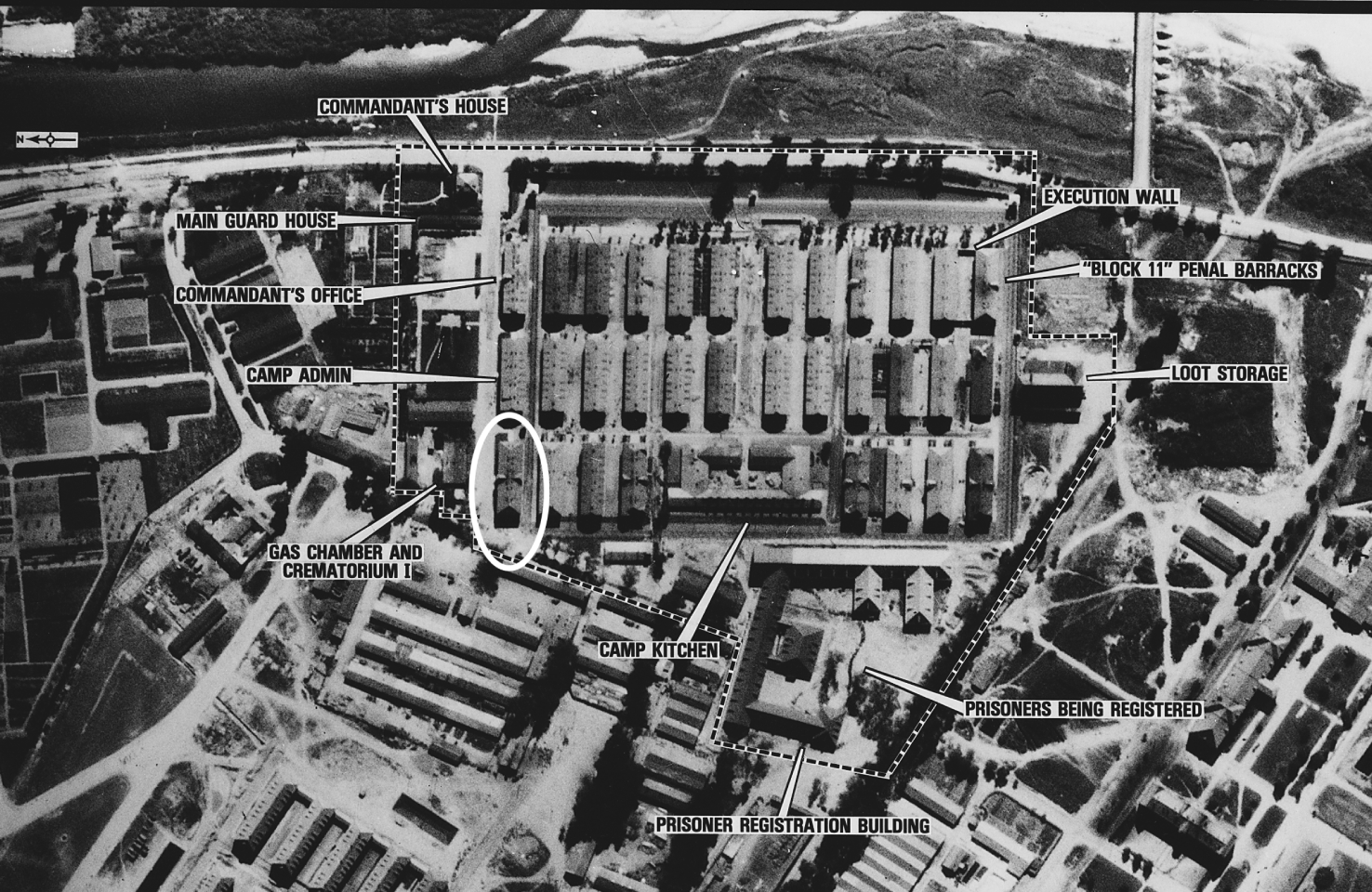

Figure 3: Location of the SS dental station (white circle). Aerial photography 25 August 1944 (NARA, NAID 305899).

The dental station also had a dental laboratory lead by SS Hauptscharführer Robert Unrath at Auschwitz.Footnote 52 Six to ten imprisoned dental technicians and two to three prisoners were assigned to this laboratory, all of whom came from the so-called ‘protective custody camp’ (Block 9). As the prisoners who were forced to work at the dental station were not allowed to remain outside of the camp’s designated prisoner areas, it was Schatz’s responsibility to pick them up at the gate of the ‘protective custody camp’ each morning.Footnote 53 Their main task was to tend to the prosthetics and metal work for the SS dental station. Also, three female prisoners were employed as receptionists.Footnote 54 Up until autumn 1943, the dental station also housed a room of the SS in which stolen jewellery and gold teeth were melted. Prisoners worked in the main camp’s melting room as well as in Birkenau’s. Prior to Schatz’s arrival, the dental station was located on the second level of the SS quarters. The office of the chief SS camp physician, the SS camp pharmacy and the concentration camp Gestapo [Politische Abteilung] were also initially housed in the same building. The dental station comprised a total of two rooms, one for consultations and the other for technical work. Once the concentration camp Gestapo moved from the SS quarters to a building to the right of Crematorium I in the late summer/early autumn of 1943, the dental station was relocated to larger quarters on the ground floor (Figure 3).Footnote 55 It included an office for the 1st SS camp dentist, two treatment rooms, a waiting room and a dental laboratory.Footnote 56 As the windows of the dental station on the ground floor directly faced Crematorium I, the prisoner dentists and the SS dentists were able to witness the events there.Footnote 57 While Willy Frank could see the interrogations and executions from the rooms of the SS dental station, Schatz could not, as the crematorium was repurposed into an air-raid shelter starting in mid-1944, before his arrival.

6 Expanded Duties for SS Dentists in the Context of Camp Maintenance

Apart from the personnel and quantitative differences cited above, the duties of the respective SS dentists also differed across the concentration and extermination camps. The assignment of two chief SS dentists at Auschwitz not only points to the higher demand for dentists there but also to the potentially varied task profiles there. However, the reconstruction of these task profiles has proven to be extremely difficult as the documents were destroyed and orders were only given orally.Footnote 58 The general range of duties and responsibilities encompassed dental treatment of SS personnel, prisoners and German civilians at the camp.Footnote 59 In his position as 1st SS camp dentist, Frank was responsible for providing overall dental services at the camp and its external camps, for collecting stolen dental gold at the SS command station and seeing to its shipment, and for creating and equipping prisoner dental stations. At Auschwitz, as well as other camps, we can see that providing treatment to prisoners did not fall within the scope of responsibilities of SS dentists. This task was instead mostly delegated to imprisoned dentists. During the Auschwitz trial, Frank proudly reported that he was able to increase the number of prisoner dental stations from thirteen to forty in the course of his time in office. In setting up these dental stations, he also reported to have always employed prisoner dentists ‘of the same nationality or race as that of the other prisoners to avoid rivalries between the staff and the patients’.Footnote 60

Schatz’s original work profile also included providing dental care to the SS guards and the civilians employed at the concentration camp. Additionally, like Frank, he also saw to the treatments of SS members’ families, for whom ‘family consultation hours’ were set up twice per week as of December 1942. Starting in 1943, female prisoners who had been assigned as domestic workers for SS families were also obligated to undergo treatments at the SS dental station.Footnote 61 Moreover, SS dentists could supplement their income by providing private treatments at the concentration camp facilities.Footnote 62

The division of duties between the two dentists also provides insights into the various positions assumed by SS personnel in everyday camp life. While Frank usually treated the SS Führer, the 2nd SS camp dentist took care of dental care of the usual guard personnel. This included the guards of the external camp, who Schatz generally visited along with an imprisoned Polish dentist.Footnote 63 The fact that the SS guards stationed there were not treated at the dental station at the main camp, but were rather seen and treated by Schatz during his weekly visits to the external camp, is indicative of how priorities were defined at the camp. In the context of managing camp operations, admitting the guards to the SS dental station would have impeded the efficient process of killings as well as the responsibilities the SS guards had at the external camp.

Despite the difference in responsibilities, Frank would also occasionally tend to SS guards at the prisoner dental stations.Footnote 64 Depending on the demands and efforts required, he supported or even replaced Schatz in these duties.Footnote 65 While at Buchenwald, the SS Führer tended to receive better dental treatment than the SS guards – including the use of fine metals for tooth replacementsFootnote 66 – it was the exact opposite at Auschwitz. Particularly for ‘the guards from the so-called Banat[,] there [was] a great need for dental prosthetics’.Footnote 67 Whenever dental gold was used for such treatments, Schatz had to issue a report to Frank, who would subsequently submit a special material request to Amt XIV of Amtsgruppe D, responsible for material deliveries and equipment for SS dental stations.Footnote 68 The complex ordering process, as well as the recorded gold deliveries sent to SS-FHA by Frank and Schatz, indicate that the dental gold used for SS Führer and SS guards came from elsewhere and not directly from the extracted and melted-down teeth of the murdered prisoners.Footnote 69 Evidently, the material deliveries came from the Degussa (Deutsche Gold- and Silberscheideanstalt) in Frankfurt am Main, a company that, in turn, made enormous profits through dental gold robberies.Footnote 70

As illustrated in the quote by Rudolf Höß cited earlier, the monitoring, removal and melting-down of dental gold was one of the central tasks undertaken by SS dentists.Footnote 71 During his provisional detention in Krakow, in 1947, Höß described the logistics of stealing dental gold: ‘The dental gold was melted down into bars by the dentists at the SS quarters and handed over to the SS-FHA every month. Precious stones of enormous value could also be found in the stolen teeth.’Footnote 72 This procedure also applied to the period prior to the relocation of the melting room. After the relocation to Crematorium III, Schatz and Frank went to monitor the removal and melting-down of the dental gold once per week.Footnote 73 They would generally only receive the processed gold, load the filled crates onto a truck and deliver them to the SS quarters.Footnote 74 They were not directly involved in extracting dental gold.

Shortly after Schatz’s arrival at Auschwitz, it became evident that there were only few differences in the practical procedures of their work in relation to their varied scopes of duty. When the deportation trains arrived, both Schatz and Frank went to the siding where they selected the Jewish dentists and technicians who would be forced to work at the dental stations. They also secured material, instruments and medicine. The material collected for the SS dental station was either stored in the attic of the SS quarters,Footnote 75 in the so-called ‘Theatre Building’, or was directly brought to a prisoner dental station.Footnote 76 Our understanding of the magnitude of robbed material and instruments is based on witness accounts given at the Frankfurt trial in 1964. At times, up to fifty suitcases filled with dentures, jaws and individual teeth could be found in the attic of the SS quarters.Footnote 77 The selection of dentists was done following the actual primary selection on the old siding.Footnote 78 Schatz and Frank would have known from the very beginning that the majority of the arriving people were selected for execution and that they were choosing among the remaining deportees who were deemed ‘able to work’.Footnote 79 From early on, their range of duties was largely subordinate to the current situation at hand, to which they were meant to conform. Particularly for areas that maintained day-to-day operations at the camp, Frank and Schatz were subject to congruent areas of responsibility.

7 The Ungarn Aktion 1944 – The Selections and Shifting Responsibilities

With the arrival of nearly 450 000 deported Jews in 137 to 147 transports originating in Hungary between 16 and 22 May 1944, the entire camp personnel at Auschwitz was confronted with the logistical problem of efficiently ‘processing’ them. Based on witness accounts, only twenty per cent of the incoming prisoners were registered. An estimated number of 325 000 to 349 000 deported Jews were sent to the gas chambers shortly after their arrival.Footnote 80 The extermination was preceded by reconstruction measures, as well as changes to the personnel within the various camps at Auschwitz. By the end of June 1943 at the latest, Crematorium III was completed, meaning that all of the crematoria at Birkenau were functioning. In November 1943, Oswald Pohl (head of the SS-WVHA) divided Auschwitz into concentration camp Auschwitz I (main camp), Auschwitz II (Birkenau) and Auschwitz III (external camp/Monowitz) and also rearranged the personnel.Footnote 81 Typical of all three camps at the time was that they were partially independent but shared certain organisational structures. One example of the inter-camp command authority was the SS Standortälteste (garrison commander) Arthur Liebehenschel (commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp since 11 November 1943), who was responsible for all three camps and the independent offices.Footnote 82 Eduard Wirths held a similar degree of authority, as he was responsible for all medical and dental matters. This overarching authority to issue orders is particularly relevant for the extended scope of duties the SS dentists assumed in the wake of the Ungarn Aktion.

At the beginning of May 1944, Oswald Pohl and Richard Glücks (head of Amtsgruppe D at the SS-WVHA) replaced Liebehenschel, and Pohl’s hitherto personal aide, Richard Baer, was assigned the role of camp commander of Auschwitz I. The leadership of the SS at Auschwitz was temporarily taken over from May to July 1944 by former Auschwitz commander Rudolf Höß, who was head of Amt D I at the time. The fact that Höß was explicitly deployed to ensure the smooth processing of the extermination transports from Hungary is not only evidenced by the completion of the rail connection in Birkenau – the so-called ‘Judenrampe’ that would henceforth end between Crematoria I and II – but also by the transfer of professional affairs to the SS Standortälteste Richard Baer at the end of July 1944. The very aim of Höß’s short-term ‘Sonderaktion’ was, in fact, extermination from the very beginning, which is why the Ungarn Aktion did not unfold as a chaotic mass murder but instead represented the radical implementation of a coordinated campaign orchestrated by Oswald Pohl. The orders by Pohl in May 1944 affected all of the camps in Auschwitz and were the ‘start of the last great rearrangement of personnel in the concentration camp system’.Footnote 83

Despite the transfer of qualified ‘extermination experts’ to Auschwitz, Eduard Wirths remained responsible for coordinating selections at the ramp [Rampendienst]. Due to the situational dynamics of the Ungarn Aktion, a larger pool of medical selection personnel was required. Therefore, Wirths resorted to all SS members assigned to his office, including dentists, pharmacists and physicians who had not witnessed any of the selections yet. The mass transports destined for Auschwitz thus caused the dentists’ duties to expand.

During a meeting with the new and extended circle of selection staff, Wirths justified the restructuring of personnel at Auschwitz with a central order from Berlin. At the same time, he informed the attending physicians about the specified minimum requirement for the selections.Footnote 84 He created a service plan for this purpose, specifically regulating who was assigned to the Rampendienst and when.Footnote 85 The service plan was posted in the rooms of the SS quarters and the orderly office. Besides Schatz, some of the others on the list included Willy Frank, Victor Capesius (1st SS pharmacist), Franz Lucas (SS physician), Bruno Kitt (SS physician) and Werner Rohde (SS physician and dentist). The service plan always specified the officeholders and those in charge of the selections as well as their deputies. Schatz and Frank alternated between the position of deputy and selection physician; according to Frank, they both shared the duty ‘on the ramp’ in equal measure.Footnote 86 During one of his first police interrogations leading up to the Frankfurt trial, Schatz claimed to have known nothing of said meeting and that he did not take part in the selections.Footnote 87 He only later acknowledged that he may have been present at the ramp between five and ten times, but that he simply ‘stood around’: ‘I walked around and pretended as though I were doing something.’Footnote 88 He strictly denied having been in charge of any of the selections, even when it was not possible to ‘always just stand around. In those cases, I escorted the transports from the ramp to a crematorium. But I did not stay there, and I also never received any orders that I have to be present during the gassing process (…)’.Footnote 89

The procedure for incoming deportation trains stipulated that the SS command headquarters was to immediately notify the orderly office, which would then inform the SS physician that he was to report for ‘ramp duty’ promptly. The ‘processing’ of the transports itself was a collaborative task; once the concentration camp Gestapo had taken over the transport, the camp leader and block leader were to open the locked doors of the car, compel the deported individuals out by yelling and beating them, and have them line up, separated by sex. The deportees’ luggage would remain in the trains so that SS members could take it to the stockroom after the selection. The relocation of the tracks to Birkenau resulted in a 600-metre-long east–west ramp that was crossed by a north–south passage in the middle. This point of intersection ‘served the camp SS as an infrastructural centre for the murderous selection process’.Footnote 90

The selection process carried out by the SS medical personnel followed a specific procedure. Deportees with medical training were brought to the first row and went directly into the camp without undergoing selection. For the remaining individuals, the block leader conducted a pre-selection and picked out those who were ‘unfit to work’; SS drivers subsequently loaded them onto trucks and took them to the gas chambers. The remaining deportees underwent a brief assessment by the SS physicians, who decided which individuals would be sent directly to the gas chambers and which would go to the camp.

Even though several witnesses testified that they recognised Schatz as part of the selection personnel,Footnote 91 and the Frankfurt chief justice stated in his judgement that there still existed a ‘strong suspicion against Doctor Schatz that he participated in the ramp service and also performed his service at the gas chambers’,Footnote 92 the Frankfurt jury court acquitted him on 19 August 1965 due to lack of evidence.

The German Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof, BGH) denied a requested review procedure from the public prosecutor’s office since Schatz’s affiliation with the

camp personnel and his knowledge of the extermination objective of the camp (…) in the end are not [sufficient] to ascribe to him the killings committed during his time at the camp. [T]he defendant did, in fact, occasionally search for ‘melted-down dental gold’ at the crematorium, supervised the work and retrieved the dental gold. That he knowingly promoted the extermination intentions of the criminal SS leadership can be excluded in light of the determinations.Footnote 93

The fact that the Frankfurt jury accepted Schatz’s protection assertion as such and refrained from prosecuting him, despite his admissions of having ridden to the ramp on his motorcycle on occasion,Footnote 94 is indicative of the problems related to legal actions toward National Socialist perpetrators.Footnote 95 One key factor in Schatz’s acquittal was the low level of weight ascribed to the witnesses who had recognised him at the ramp. Notably, the court cast doubt on the statements made by Rudolf Gibian, who pointed to a decisive bodily feature: ‘For this defendant, I saw that he had organised the prisoners to the left and the right on the ramp. I didn’t know his name. But I knew this small guy that did the work’.Footnote 96 Schatz’s personnel file did confirm that he was only 1.68 meters tall.Footnote 97 The impression that he was physically small may also have been reinforced by the fact that Schatz carried himself ‘slightly hunched over’, as former Auschwitz prisoner dentist Benjamin Jacobs noted in his autobiography.Footnote 98 The recognition value of height and posture could have served as identification features for the court.

Schatz’s involvement with the selection personnel is now considered a fact. When comparing the photographs in the Auschwitz album (the Lili Jacob album) and the so-called Karl Höcker album,Footnote 99 which both depict various selection procedures during the Ungarn Aktion, it is precisely ‘his posture and uniform [that make him] readily recognisable’ (Figure 4).Footnote 100 Schatz is shown on at least five photographs in the Auschwitz album.Footnote 101 However, they generally show him from the back or from a bird’s eye perspective. While individual pictures were part of the evidence used by the Frankfurt jury court, Schatz could not be identified due to these reasons.Footnote 102

Figure 4: Willi Schatz with his back to the camera, in the middle, slightly hunched over selecting deportees during the Ungarn Aktion 1944 (USHMM, Photo Archive, No. 77239).

It is not entirely clear whether or not Schatz assumed his new scope of duties favourably or whether he took a more distanced stance and conveyed his resentment to a few individuals. Some former prisoners, at least, did describe his behaviour at the camp as decent. Benjamin Jacobs reported that Schatz was ‘respectable and friendly’. He confided in Jacobs on various occasions and notably distanced himself from the National Socialist system. Jacobs added:

[H]is confessions were candid, he renounced the Führer (…) I often thought that people like Dr Schatz would bring the Nazi regime to its knees, but, as we know now, that did not happen (…) One day, Schatz requested that I no longer schedule any more appointments for his SS men: ‘cannot see them anymore’, he said when leaving.Footnote 103

In the recorded accounts, witness Männe Kratz is also said to have ‘got on relatively well [with Schatz]; he never did anything to me’.Footnote 104 The fact that Schatz acted differently towards the imprisoned dentists than he did in his role as a selection physician or dental gold monitor would not, however, entail contradictory behaviour. It could very well be understood as an expression of a specific National Socialist morale.Footnote 105 Specifically, concepts such as honour, loyalty and duty demarcate the horizon of moral action; they allow for complicity in National Socialist crimes and proper behaviour towards other prisoners to be harmonised with one another and be seamlessly integrated into daily tasks. However, this interpretation somewhat obscures the actual core of National Socialist perpetrator activities. The central aim was to always ensure the efficient functioning of the selections, meaning that decency could be tolerated and practised in other areas of everyday camp life, provided that it did not interfere with the efficient process of human extermination.

To reconstruct Schatz’s actual intentions based on his or other testimonies is, in our opinion, not of importance. Rather, participation in the selections itself must be seen as an enabling space for the individuals that granted them a superior position by altering task profiles. As such, being part of the selection staff can, in a way, be seen as a latent resource for promotions and a possibility for gaining social capital (Bourdieu). Such advancements were not necessarily linked to a higher pay grade or SS rank but consisted in gaining exclusivity. By being part of an exclusive group participating in the selection, one could distinguish oneself from others and gain access to the inner circles of the camp leadership. The photographs from the so-called Karl Höcker album, created nearly at the same time as the Auschwitz album, provide us with the relevant information.

While the images captured in the Auschwitz album depict Schatz as part of the selection staff, the photographs taken by Karl Höcker,Footnote 106 adjutant of the last commander Richard Baer, provide insights into the various personnel constellations Schatz came into contact with as a selection physician. Whereas Schatz had previously engaged in leisure activities, such as excursions and hunting parties, with his dentist colleagues Willy Frank and SS pharmacist Viktor Capesius,Footnote 107 the Ungarn Aktion meant his acceptance among higher-ranking camp official and SS physicians. We find Schatz in photographs such as the inauguration of the SS hospital on 1 September 1944, standing among leading SS physicians from other concentration camps and leading SS figures from concentration camps Auschwitz I, II and III. In the photograph at Figure 5, he stands directly behind Karl Höcker.Footnote 108

Figure 5: Willi Schatz, back right, wearing a peaked cap, at the opening of the SS hospital at concentration camp Auschwitz (USHMM, Photo Archive, No. 34745).

This image is relevant insofar as the opening of the Auschwitz SS hospital provided an occasion for Schatz to convene with leading SS camp physicians at Auschwitz. At an interrogation from January 1947, Heinz Baumkötter, 1st SS camp physician at the concentration camp Sachsenhausen, recollected the background of the first meeting as follows:

At the beginning of October 1944 [sic], I was ordered by the head of the medical office for concentration camps in Germany, Dr Lolling, to go to Auschwitz to attend the inauguration of the troop hospital for the camp guards (…) he had (…) ordered the head physicians from all concentration camps in Germany to attend the inauguration (…) We were shown a gas chamber, which was at least 8 × 16 m in size, and we were informed that this chamber was used to kill incoming prisoner transports from Romania, Hungary and other countries (…) During the visit, we were also shown the place where the bodies had been burned in the open air.Footnote 109

This event was less a celebratory opening of the SS hospital than an opportunity to exchange information and experiences on suitable killing practices, and to coordinate and adjust measures used by the SS medical staff in attendance. As has been demonstrated, there was an increased need among the physicians to agree on ways to contain the spread of (potential) epidemics and on how to handle hygienic challenges at the respective camps. In particular, the attendees expected to receive support in executing concentration camp prisoners.Footnote 110 Considering this background, it seems peculiar that Schatz was in attendance, yet it also indicates that he was not quite as insignificant or uninvolved as he professed before the jury in Frankfurt.

The meeting at Auschwitz took place between 1 and 3 September 1944. Following the inauguration ceremony and a few speeches, the attendees took a joint excursion to the coal mine at Brzeszce-Jawischowitz (the Andreas Pits), part of the Auschwitz external camp at Jawischowitz. Numerous prisoners at the external camp were deployed to work at this mine under orders from Hermann Göring.Footnote 111 As Baumkötter noted: ‘When visiting the pits, I noticed just how utterly tired the prisoners working there looked.’Footnote 112

Figure 6: Willi Schatz, back right, wearing light outer clothing, with leading SS physicians from other concentration camps and SS leaders at the Brzeszce-Jawischowitz coal mine (USHMM, Photo Archive, No. 34826).

The group photograph of the SS medical staff at the coal mine (Figure 6) shows (from left to right) Willi Schatz, Heinz Baumkötter, Eduard Wirths and Enno Lolling in the back row. In the front row (from left to right), we see the SS camp physician from Auschwitz–Birkenau, Fritz Klein, along with Richard Trommer (SS on-site physician at Ravensbrück), Alfred Trzebinski (SS on-site physician at Neuengamme) and the SS pharmacist from Auschwitz, Gerhard Gerber, seated in the front.Footnote 113 On photographs taken later on, we can recognise that the excursion concluded with drinks and cheerful conversations. Willi Schatz was seated next to Alfred Trzebinksi and Enno Lolling.Footnote 114

The fact that Schatz was at this meeting and actively participated in the inauguration, the excursions and the social events imply that he was much more enmeshed in the Auschwitz system and its extermination machinery than the Frankfurt jury court was ultimately able to conclude. When considering the purpose of this meeting and that Schatz was the sole dentist there, he may have assumed the role of an intermediary, informing the SS physicians in attendance about the role of dentists at Auschwitz. The Ungarn Aktion turned out to be particularly beneficial for Schatz in many regards: first and foremost, it facilitated his advancement to selection physician and, as a direct consequence, he became acquainted and fraternised with the other SS camp physicians. The mere fact that numerous meetings of camp physicians took place (though the exact number is not known) indicates that issuing orders and communicating regulations had grown increasingly informal in the context of extermination activities, fluctuating between the formal authorisations issued by Lolling and self-authorisations taken on the part of the physicians. At times, a central order to carry out extermination activities and selections was not even necessary, as the physicians presumed to take on a very broad interpretation of the responsibilities assigned to them.Footnote 115 Auschwitz served as a point of coordination and as a hub for further extermination activities and experiments performed at other concentration camps.

8 Closure of the Camps, Transfers and Court Proceedings

In autumn 1944, the disassembly of the crematoria at Auschwitz–Birkenau had been completed, followed by a restructuring of the camp complex shortly after that. By an order from 25 November 1944, Auschwitz I would receive the designation ‘Concentration Camp Auschwitz’ and Auschwitz III ‘Concentration Camp Monowitz’; concentration camp Auschwitz II ceased to exist.Footnote 116 Particularly in response to the approach of the Red Army and the aim to dissolve the camps, a large portion of the SS members involved in the Ungarn Aktion also had to be transferred. It is evident that the primary objective of these transfers was to maintain the camp system at sites located at a greater distance from the front. Schatz’s superior, Willy Frank, left Auschwitz for Dachau in late August/early September 1944 and was replaced by Elimar Precht, SS Hauptsturmführer and former SS dentist in Dachau.Footnote 117 Precht remained until the camp was abandoned in January 1945 and was then assigned to be the chief SS dentist at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp. The position of the 2nd SS camp dentist at Auschwitz was eliminated.

By the time the Red Army captured the Auschwitz camp complex on 27 January 1945 and freed its prisoners, Schatz had already been positioned in the Altreich for several months. He had been reassigned to the SS dental station at the Neuengamme concentration camp in the late autumn of 1944 and remained there in the same role as in Auschwitz – until the camp was liberated as well. The fact that the majority of the SS personnel from Auschwitz were transferred to the Altreich after the conclusion of the Ungarn Aktion indicates that, in the final months of this camp complex, the primary task was to eliminate evidence of the mass exterminations.

Schatz’s time serving at Auschwitz was shorter than the tenures of all other dentists at the various concentration camps, which generally had a duration of between one and two years.Footnote 118 As he ultimately arrived in Neuengamme and continued to work within the camp system near his hometown of Hanover, we can conclude that he took advantage of nepotism and the benefits gained through his network within the SS. When in Neuengamme, he met his old Auschwitz colleagues Eduard Wirths, Fritz Klein, Bruno Kitt and Hans Wilhelm König. The chief camp physician here was Alfred Trzebinski, whom Schatz had also met no later than September 1944 at the SS physician meeting at Auschwitz.Footnote 119

Along with providing dental treatments for SS members and their families, Schatz was once again responsible for the prisoner dental station at Neuengamme. It is unclear whether securing the collection of dental gold was also one of his duties. As at other camps, the bodies of the prisoners at Neuengamme were only released for burning once a dentist had examined them.Footnote 120 However, evidence of the activities conducted at the dental station during the final days of the concentration camp has not been found. It is also challenging to identify the extent to which Schatz was involved in coordinating the death marches and the dissolution of the concentration camp in Neuengamme. Since spring 1944, plans by the police, district administration and SS had been circulating about how to vacate the Neuengamme camp complex in the event of an Allied advance into Northern Germany.Footnote 121 By the end of March 1945, at the latest, the first clearing and evacuation efforts were put into practice by the camp leadership, primarily affecting the prisoners at the external camp. Death marches and train transports were used to accelerate the redistribution of prisoners to so-called reception camps, most located in Bergen-Belsen, Sandbostel or Wöbbelin. By the end of March, the Neuengamme concentration camp consisted of fifty-seven external camps with approximately 40 000 prisoners. Added to this figure were the nearly 12 500 prisoners at the main camp, which was filled to three times its capacity. Buggeln points out that around 14 000 prisoners were killed during the entire period of the existence of the Neuengamme main camp; from March to the beginning of May 1945, however, at least 16 000 prisoners died on account of the evacuation measures. This corresponded to approximately thirty per cent of all prisoners still being alive at the end of March.Footnote 122 By the end of April 1945, there were only around 700 prisoners remaining at the Neuengamme concentration camp. Once its files had been destroyed and its structures partially dismantled, the camp was evacuated. By the time the British army reached the camp on 2 May 1945, they found it entirely empty.

While we can reconstruct some aspects of his job profile at Auschwitz, Schatz’s duties and the positions he held at Neuengamme remain a secret. On 30 January, he was promoted at least once more to SS Obersturmführer.Footnote 123 This promotion, however, is likely linked to his responsibilities at Auschwitz. The exact date he left Neuengamme is also unknown. He most probably settled in his hometown of Hanover, where he was arrested after the end of the war and interned by the British. He was released from prison in January 1946 and got married shortly after that.Footnote 124 As opposed to his former colleagues from Auschwitz and Neuengamme, Schatz successfully reintegrated into post-war society without great difficulty. Eduard Wirths committed suicide at an internment camp in Staumühle close to Paderborn in September 1945. Bruno Kitt was executed on 8 October 1945 on the order of the British military court, as was Alfred Trzebinsky. Fritz Klein was tried at the Belsen trial in November 1945, sentenced by a British military court and executed in December 1945.Footnote 125 Up until the first police interrogation in 1960, Schatz was able to run his dental practice and live without being confronted with his past actions. This carefree life included occasional meetings with his old Auschwitz hunting comrades, Frank and Capesius.Footnote 126 Even the Auschwitz trial did not entail any significant interruption for Schatz. While the other individuals accused with him were in prison, there was no warrant issued for Schatz’s arrest.Footnote 127 That provides us with a good indication of the opinion that the public prosecutor’s office had about the role of dentists in the selections; even Willy Frank was only taken into custody shortly before the end of the trial in Frankfurt. During both the preliminary investigations and during the proceedings itself, Schatz was considered to be an uninformed camp dentist with no close associations to National Socialism:

The accused Dr Schatz was neither a staunch National Socialist nor the soldier type. (…) By the impression that the court gained of him during the main hearing, he does not personify the character of an energetic supervisor in the SS who was accustomed to giving orders in such a way that could have left some impression on his SS comrades. His duties at the Auschwitz concentration camp merely extended to (…) dental treatments for the SS personnel (…) It seems quite possible that, within the circle of SS Führer and SS physicians, he was not taken to be ‘complete’.Footnote 128

With his acquittal in August 1965, this brief waiting period had ultimately also been overcome. Up until his death on 7 February 1985, he carried on with his life at his dental practice in Hanover as an acquitted perpetrator.

9 Conclusion

Which conclusions and which new insights about the topic of dental medicine in concentration camps does our biographical sketch provide?

First, it is evident that SS dentists at Auschwitz were undoubtedly involved in the selection processes. While rightly adhering to the legal concept of ‘presumption of innocence’, the verdict at the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial also contributed to disseminate the myth of SS dentists employed in Nazi extermination camps as merely bystanders.

Second, the biography of Schatz demonstrates that physicians with interrupted party careers could once again be reintegrated due to their usefulness and current demands. Moreover, this implies that membership in the party was not decisive for performing duties at the concentration camp. How these duties were carried out on the job was of greater importance. Schatz, for one, was able to take advantage of the opportunity to start a professional career in the SS despite his flawed political past. His early contact with Hermann Pook and Enno Lolling proved pivotal for his position at the camp in Auschwitz as well as for his duties at Neuengamme.

Third, we have also been able to identify the infrastructure and the task profile of the SS dental station. The confusion of various SS offices mentioned earlier with regard to accessing the SS dental station turned out to be of lesser consequence to the SS dentists than initially assumed. Beyond robbing dental gold, the individual SS offices have instead played a subordinated role in terms of the events at the camp. The dentists could act with relative autonomy. At the least, their standing at the camp sharply differed from that of the SS physicians, and they received less attention from the camp leadership. This particular form of autonomy became apparent when their roles changed, leading up to the Ungarn Aktion. The selection of dental materials and personnel did not entail a prescribed task or requirement; instead, it emerged from self-motivation intending to equip the dental station as adequately as possible. Likewise, this kind of autonomy included setting up and providing the prisoner dental stations, as well as delegating the task of treating prisoners to the imprisoned dentists. Schatz quickly became acquainted with these conditions and procedures at Auschwitz upon his arrival, adapting his demeanour accordingly to this model. Incursions into this autonomy among the dentists can first be identified in the context of the Ungarn Aktion. The relatively independent medical sub-areas at the camp helped Eduard Wirths, in particular, to amass higher authority after he concentrated and centralised these areas for the sake of maximising the efficient processing of the incoming transports.

Fourth, the biography allows us to identify the processes and situational dynamics informing the final expansion phase of the concentration camps. The events surrounding the Ungarn Aktion, in particular, shed light on the integrative and collaborative character of systematic extermination at Auschwitz. While dentists assigned to other concentration camps had previously been involved in experiments and killings,Footnote 129 the Ungarn Aktion shows that this was not so much a matter of individual involvement but rather one of ensuring that the orchestrated whole functioned smoothly. For the camp leadership, the Ungarn Aktion represented a challenge that needed to be mastered collectively. For the SS dentists, this ultimately meant that their duties would temporarily be expanded. Their involvement in the selections was, therefore, a result of changing conditions to which they had to alter their scope of responsibilities dynamically.Footnote 130

Fifth, the Ungarn Aktion offers us a suitable analytical frame of reference for uncovering both complicity in the activities, as well as the associated benefits attained by those involved. When the court painted Schatz as an SS medical doctor who was unable to find recognition, and when we also consider his membership in the NSDAP and the SA, we can infer an underlying motivation behind his actions. Already his early party membership, as well as his behaviour in the context of his fiancée’s abortion, indicate that Schatz had a positive attitude towards the ideological demands of National Socialism.Footnote 131 From a political perspective, he was thus able to ‘rehabilitate’ himself through active involvement during the Ungarn Aktion. Nevertheless, neither his allegedly distanced political view nor his National Socialist convictions played a role in performing his duties, provided that these did not inhibit him from satisfying his responsibilities as part of the selection staff. From a professional perspective, the involvement of the dentists in the selections signifies that they also decided on matters of life or death, just as the SS physicians did; at least in this specific case, their status was equal to that of the physicians. Additionally, involvement in the selections also allowed Schatz to be invited to the meeting of SS physicians in September 1944, where he could exchange expertise and experience with other SS medical staff. Considering this, the role as selection physician offered access to further networking opportunities within the SS.

Sixth, Schatz’s relocation to Neuengamme, along with some of his Auschwitz colleagues, indicates that clusters were being reassigned together. Being acquainted with and sharing experiences with the SS physicians brought a certain degree of continuity to daily life and work at the concentration camps. In the case of Schatz, we can only guess the degree of access he had to such a network structure due to his short period of deployment. It becomes more evident when we consider the leadership cadres at Auschwitz, nearly all of who came from Dachau.Footnote 132 Future studies could use this observation as a point of departure for shedding more light on this system of networks in relation to dentists as well.

As mentioned at the outset, Schatz was merely one example of many SS camp dentists, which hardly makes his specific patterns of behaviour attributable to other SS camp dentists or conditions at other concentration and extermination camps. For additional camps and other personnel constellations, different questions and propositions could very well prove to be more fruitful. Further research on this topic should draw on a broad empirical basis of evidence for this group of perpetrators in order to arrive at possible commonalities. Some pertinent questions include: How did the task profile of SS dentists change after the start of the war? How did it change once again in the face of impending defeat? How were SS dentists recruited and were there any camp systems that were particularly attractive for the dentists? Several indications show that Oranienburg/Sachsenhausen served as an equally functional education and training ground for the (dental) medicine personnel of the camp SS as did Dachau concerning the rise of numerous future SS camp commanders.Footnote 133 How did this relationship between the SS dentists and the SS physicians take shape? In what areas did forms of cooperation take place and in what areas did conflicts arise? Did any significant difference in task profiles exist between the SS dentists, depending on the function of the respective camp? Which career paths can we identify? And, lastly, another issue would be whether or not general statements can be made about the post-war careers of these individuals.

Several of these questions can be answered with reference to Willi Schatz and the camp complex in Auschwitz. One key finding is that involvement in the selections did not require individuals to hold radical political convictions. Former Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner Hermann Langbein made an essential point in this regard during the Auschwitz trial: ‘Killing a person was a light matter, it was not even worth discussing. (…) Many were not utterly fanatical or anti-Semitic. (…) Dr Schatz and Dr Frank did not do anything bad to us prisoners. But, in the atmosphere of Auschwitz, none of them had any apparent reservations about bringing people to the gas [chamber].’Footnote 134 It is evident that the most important task performed by both SS dentists was to ensure that the extermination of human beings proceeded smoothly.